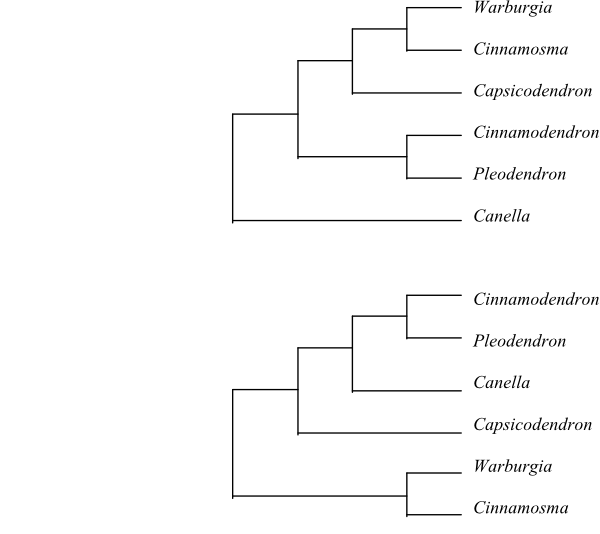

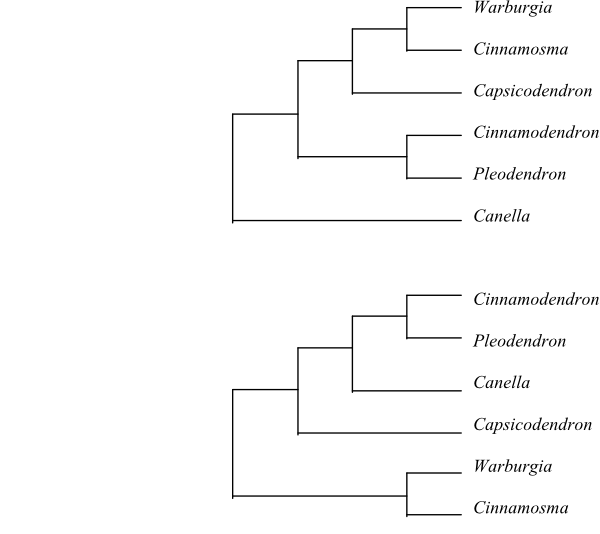

Cladograms of Canellaceae based on DNA sequence data (Karol & al. 2000 [upper and lower]; Marquínez & al. 2009 [upper]).

Winterales A. C. Sm. ex Reveal in Phytologia 74: 174. 25 Mar 1993; Winteranae Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.: xxiii. 23 Dec 2001; Winteridae Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.: xxiii. 23 Dec 2001; Winterineae Shipunov in A. Shipunov et J. L. Reveal, Phytotaxa 16: 64. 4 Feb 2011

Habit Usually bisexual (rarely monoecious, polygamomonoecious or dioecious), evergreen trees (rarely shrubs). Aromatic.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza? Phellogen ab initio superficial. Primary stem with eustele or (pseudo)siphonostele, with continuous vascular cylinder. Vessel elements absent in Winteraceae. Vessel elements in Canellaceae with scalariform, opposite or reticulate perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform or opposite, bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids with bordered pits, non-septate (often also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal aliform, confluent or vasicentric, or in bands. Sieve tube plastids Ss, Psc or Psf type. Nodes usually 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces (rarely bilacunar). Parenchyma with oil cells. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals often frequent.

Trichomes Hairs usually absent.

Leaves Alternate (spiral or distichous), simple, entire, coriaceous, with supervolute ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate to amphicribral. Venation pinnate, brochidodromous. Stomata usually paracytic (sometimes anomocytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids as rodlets or tubuli (often as clustered tubuli of Berberis type), chemically dominated by nonacosan-10-ol. Mesophyll with calciumoxalate druses, and idioblasts with sclereids (often branched), ethereal oils or resins. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, compound, fasciculate, or raceme-like, or flowers solitary.

Flowers Actinomorphic. Hypogyny. Outer tepals two to four (to six), spiral or whorled, with valvate or imbricate aestivation, sepaloid, free or connate at base; inner tepals (one or) two to more than 50, with imbricate aestivation, usually petaloid, spiral or in one, two or four whorls, usually free (sometimes connate in lower parts; rarely absent). Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens three to more than 100, spiral or whorled. Filaments free from each other or connate into tube, free from tepals. Microsporangia adaxial, abaxial, lateral or apical, non-versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (rarely disporangiate), usually latero-extrorse (sometimes extrorse or subintrorse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory or amoeboid-periplasmodial. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis usually simultaneous (rarely successive). Pollen grains monoporate or monosulcate to trichotomosulcate, shed as monads or tetrads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate (rarely intectate), usually with columellate (rarely intermediary) infratectum, reticulate, microreticulate, or perforate.

Gynoecium Carpels one to more than 50, spiral, free or more or less connate, often not differentiated into ovary and style, often incompletely closed at anthesis, or carpels two to six connate into pistil; carpel conduplicate to plicate (rarely ascidiate), postgenitally completely or incompletely closed with or without an open canal filled with secretions. Ovary superior, unilocular to 20-locular. Style single, simple, or absent (pollen tube transmitting tissue well developed). Stigma apical or stigmas decurrent, papillate, Wet type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation axile, laminar-lateral, submarginal or parietal. Ovules (one or) two to more than 100 per carpel, anatropous, hemianatropous or campylotropous, descending to ascending, apotropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle bistomal, often Z-shaped (zig-zag). Nucellar cap at least usually present. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Synergids at least usually with a filiform apparatus. Endosperm development cellular. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis often irregular.

Fruit A syncarp with berry-like fruitlets, capsule, an assemblage of berries or a berry with persistent outer tepals.

Seeds Aril usually absent. Seed coat exotestal. Exotesta palisade, sclerotic. Mesotesta and endotesta unspecialized. Tegmen usually unspecialized. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, oily (sometimes ruminate). Embryo small to large, straight or slightly curved, well differentiated, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 11, 13, 14, 18 (43)

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols (quercetin, dihydroquercetin), flavones, cyanidin monoterpenes, drimane sesquiterpenoids, proanthocyanidins, aporphine alkaloids, N-(cinnamoyl)-tryptamines, and lignoids present. Ellagic acids not found.

Systematics Canellaceae, Winteraceae.

CANELLACEAE Mart. |

Winteranaceae Warb. in Engler et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam., III, 6: 314. 14 Mai 1895 [’Winteranaceae (Canellaceae)’], nom. illeg.

Genera/species 5/21

Distribution Tropical East Africa, northeastern South Africa, Madagascar, southeastern United States, the West Indies, tropical South America.

Fossils Eocene wood, Wilsonoxylon edenense, was found in Wyoming (Boonchai & Manchester 2012). An ambiguous pollen fossil from the Oligocene of Puerto Rico is ascribed to Pleodendron (Friis & al. 2011).

Habit Bisexual, usually evergreen trees (rarely shrubs). Aromatic.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio superficial. Primary stem with continuous vascular cylinder a (pseudo)siphonostele. Cortical vascular system present. Vessel elements with scalariform, opposite or reticulate perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform or opposite, bordered pits. Vestured pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids with bordered pits, non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal aliform, confluent or vasicentric. Sieve tube plastids usually Psc type (in Canella Psf type, with fibrils but without protein crystalloids). Nodes usually 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces (sometimes bilacunar). Parenchyma with oil cells. Heartwood with gum-like substances etc. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals abundant.

Trichomes Hairs absent.

Leaves Alternate (spiral or distichous), simple, entire, coriaceous, with supervolute? ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate. Lamina often gland-dotted. Venation pinnate. Stomata anomocytic (Cinnamosma, Warburgia) or paracytic (Canella, Cinnamodendron, Pleodendron). Cuticular wax crystalloids as rodlets or clustered tubuli (Berberis type), chemically dominated by nonacosan-10-ol. Mesophyll with crystal druses, and idioblasts with ethereal oils (and idioblasts with branched sclereids?). Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, compound, cymose (Canella) or raceme-like, or flowers solitary axillary. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) two, lateral.

Flowers Actinomorphic. Hypogyny. Outer tepals (bracts?) three, with imbricate aestivation, alternate or whorled, sepaloid, coriaceous, free or connate at base; inner tepals (three to) five to twelve, with imbricate aestivation, petaloid, spiral or in one, two or four series, usually free (in Canella connate at base; in Cinnamosma connate to a tube at lower part). Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens usually six to twelve (in Cinnamosma c. 35 to 40), whorled. Filaments connate into a tube, free from tepals. Anthers abaxial (inserted at abaxial side of staminal tube), non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, extrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal valves); connective often prolonged. Tapetum secretory. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains monosulcate to trichotomosulcate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine usually tectate (sometimes semitectate), with columellate to intermediary infratectum, perforate to psilate (in Cinnamosma intectate, reticulate).

Gynoecium Pistil composed by two to six paracarp and connate carpels; carpel plicate, postgenitally incompletely fused, occluded by secretion, with open canal filled by secretions; internal compitum present. Ovary superior, unilocular. Style single, simple, short, thick. Stigmatic lobes two to six, papillate, type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation parietal, with two to six massive placentae. Ovules two to more than 100 per carpel, hemianatropous to campylotropous, horizontal to ascending, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle bistomal, Z-shaped (zig-zag). Outer integument two to four cell layers thick. Inner integument two or three cell layers thick. Ovules in Cinnamosma possibly pachychalazal? Nucellar cap absent. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development cellular? Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A two- to multi-seeded berry with persistent outer (sepaloid) tepals.

Seeds Seeds in Canella and Pleodendron with rudimentary aril. Seed coat exotestal. Exotesta sclerotic (other parts indistinct). Mesotesta and endotesta unspecialized. Tegmen unspecialized. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious (in Canella and Cinnamosma ruminate), oily. Embryo small to relatively large, straight or slightly curved, well differentiated, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Germination?

Cytology n = 11, 13, 14

DNA

Phytochemistry Monoterpenes, drimane sesquiterpenoids, aporphine alkaloids, N-(cinnamoyl)-tryptamines, and lignoids present. Flavonols, ellagic acid and proanthocyanidins not found. Aluminium not accumulated.

Use Timber, aromatic tonics, medicinal plants.

Systematics Canella (1; C. winterana; southern part of Florida Keys, Cape Sable, the West Indies Yucatan, Central America), Pleodendron (7; P. costaricense: Costa Rica; P. ekmanii, ‘Cinnamodendron angustifolium’, ‘Cinnamodendron ekmanii’: Hispaniola; P. macranthum: Puerto Rico; ‘Cinnamodendron corticosum’: Jamaica; ‘Cinnamodendron cubense’: Cuba), Cinnamosma (3; C. fragrans, C. macrocarpa, C. madagascariensis; Madagascar), Warburgia (4; W. elongata, W. salutaris, W. stuhlmannii, W. ugandensis; tropical East Africa, northeastern South Africa), Cinnamodendron (6; C. venezuelense: northeastern Venezuela; C. tenuifolium: Suriname; C. axillare, C. dinisii, C. occhionianum, C. sampaioanum: southern Brazil).

Canellaceae are sister to Winteraceae. The Central American-West Indian species Canella winterana is sister to the remaining Canellaceae, according to Marquínez & al. (2009) and Müller & al. (2015).

|

Cladograms of Canellaceae based on DNA sequence data (Karol & al. 2000 [upper and lower]; Marquínez & al. 2009 [upper]). |

|

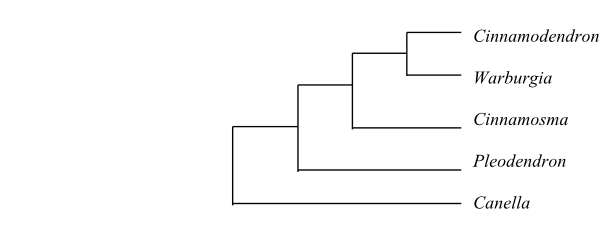

Cladograms of Canellaceae based on DNA sequence data (Müller & al. 2015). |

WINTERACEAE R. Br. ex Lindl. |

Drimyidaceae (Baill.) Baill. in Adansonia 7: 383, 384. Aug 1867 [‘Drimydeae’]; Takhtajaniaceae (J.-F. Leroy) J.-F. Leroy in Adansonia, sér. 2, 20: 20. 30 Mai 1980

Genera/species 5/c 110

Distribution Northern Madagascar, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, New Guinea, Moluccas to Solomon Islands, eastern Australia, Tasmania, Lord Howe, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Mexico to Magellan’s Strait, Juan Fernández Islands, with their highest diversity in Queensland and New Caledonia. Mainly in subtropical montane forests.

Fossils Walkeripollis are fossil pollen tetrads with reticulate exine and columellate infratectum described from the Late Barremian or the Early Aptian of Gabon and from the Late Aptian to the Early Albian of Israel. Pseudowinterapollis was described from the Campanian to the Maastrichtian of Australia. The fossil wood Winteroxylon has been found in Late Santonian to Early Campanian layers from James Ross Island, Antarctica. Cenozoic records of Winteraceae are known from Germany, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Antarctica and South America.

Habit Usually bisexual (sometimes monoecious or polygamomonoecious; Tasmannia usually dioecious), evergreen trees or shrubs (rarely epiphytic; Drimys piperita with lignotuber). Wood aromatic.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio superficial. Primary stem with continuous vascular cylinder as eustele or (pseudo)siphonostele. Medulla sclerenchymatous. Pericyclic sclerenchyma of various origin. Vessels absent. Vestured pits present. Imperforate tracheary elements tracheids with usually two or three rows of circular bordered pits (in some species of Zygogynum sometimes with scalariform perforation plates), non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays multiseriate (up to more than 10-seriate), heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse, diffuse-in-aggregates or in tangential bands. Sieve tube elements without sharp distinction between sieve surfaces of sieve plates and lateral sieve surfaces. Sieve tube plastids Ss type (Drimys, Pseudowintera) or Psc type (Drimys, Tasmannia, Zygogynum), with few to numerous starch grains. Nodes 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces. Parenchyma with oil cells. Sclereids and calciumoxalate crystals (prismatic?, druses?) often abundant.

Trichomes Hairs usually absent (in Pseudowintera uniseriate).

Leaves Alternate (spiral), simple, entire, coriaceous, with supervolute ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate or hippocrepomorphic to amphicribral. Venation pinnate, brochidodromous. Stomata usually paracytic (in Takhtajania mostly anomocytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids as clustered tubuli (Berberis type), chemically dominated by nonacosan-10-ol. Mesophyll with idioblasts with ethereal oils, sclerenchymatic idioblasts (with branched sclereids) and cells with isoprenoid resins. Lamina often gland-dotted. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, fasciculate or other cymose inflorescence types, or flowers solitary. Floral prophylls (bracteoles)?

Flowers Usually actinomorphic (sometimes slightly bisymmetric). Hypogyny. Outer tepals two to four (to six), spiral to almost whorled, with valvate aestivation, sepaloid, caducous, often connate in bud to an early dehiscent calyptra; inner tepals two to more than 50 (rarely one), with imbricate aestivation, usually petaloid, usually free (rarely absent). Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens three to more than 100 (very rarely up to c. 370), spiral. Filaments thick, foliaceous, free from each other and from tepals. Microsporangia dorsal, lateral or apical, non-versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (rarely disporangiate), usually latero-extrorse (sometimes subintrorse; thecae sometimes transversely arranged; ’sides’ of thecae sometimes erect), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective often undeveloped (in Zygogynum sometimes prolonged). Tapetum secretory or amoeboid-periplasmodial. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis usually simultaneous (in Drimys and Pseudowintera successive). Pollen grains usually monoporate (rarely monosulcate; in Takhtajania monoporate to trichotomosulcate), usually shed as acalymmate tetrads (in four species of Zygogynum as monads), bicellular at dispersal. Exine usually semitectate (rarely tectate), with columellate infratectum, usually reticulate (in Zygogynum sometimes microreticulate).

Gynoecium Carpels few to more than 50 (in Pseudowintera traversii usually one; in Takhtajania two), spiral, free or partially connate (in Zygogynum syncarpously connate; in Takhtajania paracarpously connate forming usually unilocular pistil); carpel usually plicate (sometimes secondarily? ascidiate), without canal, foliaceous, stipitate or sessile, often not differentiated into ovary and style, incompletely closed during anthesis and postgenitally completely occluded, or completely closed and with short stylodium; internal compitum present in Takhtajania, partial compitum present in Pseudowintera and Zygogynum. Ovary superior, unilocular (often apocarpy, rarely monomerous), or bi- to 20-locular. Style single or absent. Stigma apical (on style) or stigmas decurrent (on ovaries without style), papillate, Wet type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation axile (when ovary syncarpous) or laminar-lateral, laminar-diffuse or submarginal (apical-subapical?; in Takhtajania parietal). Ovules (one to) five to more than 100 per carpel, anatropous, descending, apotropous, bitegmic, crassinucellate. Micropyle bistomal. Outer integument three two five cell layers thick. Inner integument two to four cell layers thick. Nucellar cap present. Parietal tissue two to six cell layers thick. Hypostase present. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Synergids with a filiform apparatus. Endosperm development cellular. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis irregular.

Fruit A syncarp with berry-like fruitlets (sometimes hard due to presence of stone cells), a capsule or an assemblage of berries.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat exotestal. Exotesta palisade, sclerotic, composed of epidermis of outer integument. Mesotesta and endotesta unspecialized. Exotegmen unspecialized. Endotegmen sometimes subfibrous. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, oily. Embryo very small, well differentiated, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 13 (Tasmannia), 18 (Takhtajania), 43 (Drimys) – Polyploidy rarely occurring (Zygogynum baillonii, 2n = 172).

DNA The mutation velocity of ITS rDNA seems to have been remarkably slow.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (quercetin, dihydroquercetin), flavones, prenylated flavanones, cyanidin, monoterpenes, drimane sesquiterpenoids, proanthocyanidin, and lignoids present. Alkaloids not found (or present in some species?). Ellagic acid not found. Aluminium accumulated in some species.

Use Ornamental plants, medicinal plants (Drimys).

Systematics

Winteraceae are sister group to Canellaceae with very high support.

The absence of vessels in the wood (replaced by tracheids) and the presence of plicate carpels are secondarily derived (Young 1981; Marquínez & al. 2009). The stomata in many species of Winteroideae are provided with plugs of wax and cutin, that close the stomatal apertures in order to prevent them from rain water. This is interpreted as a secondary adaptation to moist (southern) temperate and mountainous habitats (Marquínez & al. 2009).

Winteraceae have a very disjunct distribution. Takhtajania occurs in a small rainforest area in northeastern Madagascar. Tasmannia has its main distribution in eastern Australia, Tasmania and New Guinea, but is also present on Borneo, Sulawesi and in the Philippines. Drimys is distributed from southern Mexico to northernmost Peru, in southeastern Brazil and in the southern parts of Chile, and Juan Fernández. Pseudowintera is endemic in New Zealand. Zygogynum (now including Belliolum, Bubbia and Exospermum) occurs in eastern Australia, New Guinea, New Caledonia and the Moluccas. Fossil Winteraceae are known from many places outside their extant distribution: Central and southern Africa, Israel, Germany, Argentina and Antarctica. This indicates that the group was widely distributed during the Cretaceous and the Paleogene, above all on the Gondwanan continents. From the Oligocene onwards the distribution seems to have declined gradually, most probably accompanied by large-scale extinctions. Much of the speciation of, e.g., Drimys and Pseudowintera, probably took place after the Miocene uplift of the Central Andes and New Zealand (Marquínez & al. 2009).

Takhtajanioideae J.-F. Leroy in Adansonia, sér. 2, 17: 393. 1978

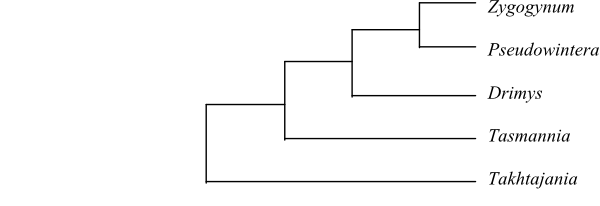

1/1. Takhtajania (1; T. perrieri; northeastern Madagascar). – Dioecious tree. Stomata usually anomocytic. Pollen grains monoporate to trichotomosulcate. Pollen tetrads larger than in Winteroideae. Carpels two, paracarpously connate. Placentation subapical-parietal. Outer integument four or five cell layers thick. Inner integument two to four cell layers thick. Parietal tissue five or six cell layers thick. n = 18. – Takhtajania perrieri is sister to the remaining Winteraceae.

Winteroideae

4/c 110. Tasmannia (c 40; the Philippines, Borneo, Sulawesi, New Guinea, eastern Australia), Drimys (c 8; southern Mexico to southern Patagonia), Pseudowintera (3; P. axillaris, P. colorata, P. traversii; New Zealand, Stewart Island), Zygogynum (c 60; New Caledonia). – Disjunct distribution on the Southern Hemisphere. Bisexual or dioecious (most species of Tasmannia) trees or shrubs. Vestured pits sometimes present in tracheids. Sieve elements with non-dispersive protein bodies. Stomata usually paracytic. Carpels (one to) five to numerous. Outer integument three or four cell layers thick. Inner integument two or three cell layers thick. Parietal tissue two to five cell layers thick. Fruit berry-like (sometimes a follicle). Sesquiterpene dialdehyde cinnamates present. n = 13, 43. – Tasmannia, sister to the clade [Drimys+[Pseudowintera+Zygogynum]], has larger chromosomes, and the interphase nuclei are different from those in Drimys (Ehrendorfer & Lambrou 2000).

|

Cladogram of Winteraceae based on DNA sequence data (Marquínez & al. 2009). |

Literature

Bailey IW. 1944. The comparative morphology of the Winteraceae III. Wood. – J. Arnold Arbor. 25: 97-103.

Bailey IW, Nast CG. 1943a. The comparative morphology of the Winteraceae VII. Summary and conclusions. – J. Arnold Arbor. 24: 37-47.

Bailey IW, Nast CG. 1943b. The comparative morphology of the Winteraceae I. Pollen and stamens. – J. Arnold Arbor. 24: 340-346.

Bailey IW, Nast CG. 1943c. The comparative morphology of the Winteraceae II. Carpels. – J. Arnold Arbor. 24: 472-481.

Bailey IW, Nast CG. 1944a. The comparative morphology of the Winteraceae IV. Anatomy of the node and vascularization of the leaf. – J. Arnold Arbor. 25: 215-221.

Bailey IW, Nast CG. 1944b. The comparative morphology of the Winteraceae V. Foliar epidermis and sclerenchyma. – J. Arnold Arbor. 25: 342-348.

Bailey IW, Thompson WP. 1918. Additional notes upon the angiosperms Tetracentron, Trochodendron, and Drimys, in which vessels are absent from wood. – Ann. Bot. 32: 503-512.

Baranova M. 1972. Systematic anatomy of the leaf epidermis in the Magnoliaceae and some related families. – Taxon 21: 446-469.

Baranova M. 2004. The stomatal apparatus of Takhtajania perrieri (Capuron) M. Baranova & J.-F. Leroy (Winteraceae). – Kew Bull. 59: 141-144.

Barros F de, Salazar J. 2009. Cinnamodendron occhionianum, a new species of Canellaceae from Brazil. – Novon 19: 11-14.

Bastos JK, Kaplan MAC, Gottlieb OR. 1999. Drimane-type sesquiterpenoids as chemosystematic markers of Canellaceae. – J. Brazilian Chem. Soc. 10: 136-139.

Behnke H-D. 1988. Sieve-element plastids, phloem protein, and evolution of flowering plants III. Magnoliidae. – Taxon 37: 699-732.

Behnke H-D, Kiritis U. 1983. Ultrastructure and differentiation of sieve elements in primitive angiosperms I. Winteraceae. – Protoplasma 118:148-156.

Bhandari NN. 1963. Embryology of Pseudowintera colorata – a vesselless dicotyledon. – Phytomorphology 13: 303-316.

Bhandari NN, Venkataraman R. 1968. Embryology of Drimys winteri. – J. Arnold Arbor. 49: 509-524.

Bongers JM. 1973. Epidermal leaf characters of the Winteraceae. – Blumea 21: 381-411.

Bonnet E. 1876. Essaie d’une monographie des Canellacées. – Paris.

Boonchai N, Manchester SR. 2012. Systematic affinities of early Eocene petrified woods from Big Sandy Reservoir, southwestern Wyoming. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 173: 209-227.

Cai Z, Penaflor C, Kuehl JV, Leebens-Mack J, Carlson JE, dePamphilis CW, Boore JL, Jansen RK. 2006. Complete chloroplast genome sequences of Drimys, Liriodendron, and Piper: implication for the phylogeny of magnoliids. – BMC Evol. Biol. 6: 77.

Canonica L, Corgella A, Gariboldi P, Jommi G, Křepinský J, Ferrari G, Casagrande C. 1969. Sesquiterpenoids of Cinnamosma fragrans Baillon: structure of cinnamolide, cinnamosmolide and cinnamodial. – Tetrahedron 25: 3895-3902.

Capuron R. 1963. Présence à Madagascar d’un nouveau représentant (Bubbia perrieri R. Capuron) de la famille des Wintéracées. – Adansonia, sér II, 3: 373-378.

Carlquist SJ. 1981. Wood anatomy of Zygogynum (Winteraceae); field observations. – Bull. Mus. Natl. Hist. Nat. Paris, sér. IV, Adansonia 3B: 281-292.

Carlquist SJ. 1982. Exospermum stipitatum (Winteraceae): observations on wood, leaves, flowers, pollen, and fruit. – Aliso 10: 277-289.

Carlquist SJ. 1983a. Wood anatomy of Belliolum (Winteraceae) and note on flowering. – J. Arnold Arbor. 64: 161-169.

Carlquist SJ. 1983b. Wood anatomy of Bubbia (Winteraceae), with comments on origin of vessels in dicotyledons. – Amer. J. Bot. 70: 578-590.

Carlquist SJ. 1988. Wood anatomy of Drimys s.s. (Winteraceae). – Aliso 12: 81-95.

Carlquist SJ. 1989. Wood anatomy of Tasmannia; summary of wood anatomy of Winteraceae. – Aliso 12: 257-275.

Carlquist SJ. 2000. Wood and bark anatomy of Takhtajania (Winteraceae): phylogenetic and ecological implications. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 87: 317-322.

Coetzee JA, Praglowski J. 1988. Winteraceae pollen from the Miocene of the southwestern Cape (South Africa): relationship to modern taxa and phytogeographical significance. – Grana 27: 27-37.

De Boer R, Bouman F. 1974. Integumentary studies in the Polycarpicae III. Drimys winteri (Winteraceae). – Acta Bot. Neerl. 23: 19-27.

Deroin T. 2000. Notes on the vascular anatomy of the fruits of Takhtajania (Winteraceae) and its interpretation. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 87: 398-406.

Deroin T, Leroy J-F. 1993. Sur l’interprétation de la vascularisation ovarienne de Takhtajania (Wintéracées). – Compt. Rend. Acad. Sci. Paris 316: 725-729.

Doust AN. 2000. Comparative floral ontogeny in Winteraceae. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 87: 366-379.

Doust AN. 2001. The developmental basis of floral variation in Drimys winteri (Winteraceae). – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 162: 697-717.

Doust AN, Drinnan AN. 2004. Floral development and molecular phylogeny support the generic status of Tasmannia (Winteraceae). – Amer. J. Bot. 91: 321-331.

Doyle JA. 2000. Paleobotany, relationships, and geographic history of Winteraceae. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 87: 303-316.

Doyle JA, Hotton CL, Ward JV. 1990a. Early Cretaceous tetrads, zonasulculate pollen, and Winteraceae I. Taxonomy, morphology, and ultrastructure. – Amer. J. Bot. 77: 1544-1557.

Doyle JA, Hotton CL, Ward JV. 1990b. Early Cretaceous tetrads, zonasulculate pollen, and Winteraceae II. Cladistic analysis and implications. – Amer. J. Bot. 77: 1558-1568.

Ehrendorfer F, Lambrou M. 2000. Chromosomes of Takhtajania, other Winteraceae, and Canellaceae: phylogenetic implications. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Garden 87: 407-413.

Ehrendorfer F, Silberbauer-Gottsberger I, Gottsberger G. 1979. Variation on the population, racial and species level in the primitive relic angiosperm genus Drimys (Winteraceae) in South America. – Plant Syst. Evol. 132: 53-83.

Endress PK, Igersheim A, Sampson FB, Schatz GE. 2000. Floral structure of Takhtajania and its systematic position in Winteraceae. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 87: 347-365.

Erbar C, Leins P. 1983. Zur Sequenz von Blütenorganen bei einigen Magnoliiden. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 103: 433-449.

Esau K, Cheadle VI. 1984. Anatomy of the secondary phloem in Winteraceae. – IAWA Bull., N. S., 5: 13-43.

Field TS, Holbrook NM. 2000. Xylem sap flow and stem hydraulics of the vesselless angiosperm Drimys granadensis (Winteraceae) in a Costa Rican elfin forest. – Plant Cell Envir. 23: 1067-1077.

Field TS, Zwieniecki MA, Donoghue MJ, Holbrook NM. 1998. Stomatal plugs of Drimys winteri (Winteraceae) protect leaves from mist but not drought. – Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95: 14256-14259.

Field TS, Zwieniecki MA, Holbrook NM. 2000. Winteraceae evolution: an ecophysiological perspective. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 87: 323-334.

Field TS, Brodribb T, Holbrook NM. 2002. Hardly a relict: freezing and the evolution of vesselless wood in Winteraceae. – Evolution 56: 464-478.

Fiser J, Walker D. 1967. Notes on the pollen morphology of Drimys Forst., section Tasmannia (R. Br.) F. Muell. – Pollen Spores 9: 229-239.

Frame D. 2003. The pollen tube pathway in Tasmannia insipida (Winteraceae): homology of the male gametophyte conduction tissue in angiosperms. – Plant Biol. 5: 290-296.

Gilg E. 1925. Canellaceae. – In: Engler A (ed), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien, 2. Aufl., Bd. 21, W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 323-328.

Godley EJ, Smith DH. 1981. Breeding system in New Zealand plants 5. Pseudowintera colorata (Winteraceae). – New Zealand J. Bot. 19: 151-156.

Gottlieb OR, Kaplan MAC, Kubitzki K, Toledo Barros R. 1989. Chemical dichotomies in the Magnolialean complex. – Nord. J. Bot. 8: 437-444.

Gottsberger G, Silberbauer-Gottsberger I, Ehrendorfer F. 1980. Reproductive biology in the primitive relic angiosperm Drimys brasiliensis (Winteraceae). – Plant Syst. Evol. 135: 11-39.

Graham A, Jarzen D. 1969. Studies in Neotropical paleobotany I. The Oligocene communities of Puerto Rico. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 56: 308-357.

Grímsson F, Grimm GW, Potts A, Zetter R, Renner SS. 2017. A Winteraceae pollen tetrad from the early Paleocene of western Greenland, and the fossil record of Winteraceae in Laurasia and Gondwana. – J. Biogeogr. 2017. doi: 10.1111/jbi.13154

Ham R van der, Heuven BJ van. 2002. Evolutionary trends in Winteraceae pollen. – Grana 41: 4-9.

Hammel BE, Zamora NA. 2005. Pleodendron costaricense (Canellaceae), a new species for Costa Rica. – Lankesteriana 5: 211-218.

Hotchkiss AT. 1955. Chromosome numbers and pollen tetrad size in the Winteraceae. – Proc. Linn. Soc. New South Wales 79-80: 47-53.

Igersheim A, Endress PK. 1997. Gynoecium diversity and systematics of the Magnoliales and winteroids. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 124: 213-271.

Jeffrey EC, Cole RD. 1916. Experimental investigations on the genus Drimys. – Ann. Bot. 30: 359-368.

Kagata T, Saito S, Shigemori H, Ohsaki A, Ishiyama H, Kubota T, Kobayashi J. 2006. Paratunamides A-D, oxindole alkaloids from Cinnamodendron axillare. – J. Nat. Prod. 69: 1517-1521.

Karol KG, Suh Y, Schatz GE, Zimmer E. 2000. Molecular evidence for the phylogenetic position of Takhtajania in the Winteraceae: inference from nuclear ribosomal and chloroplast gene spacer sequences. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 87: 414-432.

Keating RC. 2000. Anatomy of the young shoot of Takhtajania perrieri (Winteraceae). – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 87: 335-346.

Kubitzki K. 1993. Canellaceae. – In: Kubitzki K, Rohwer JG, Bittrich V (eds), The families and genera of vascular plants II. Flowering plants. Dicotyledons. Magnoliid, hamamelid and caryophyllid families, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 200-203.

Kubitzki K, Vink W. 1967. Flavonoid-Muster der Polycarpicae als systematisches Merkmal II. Untersuchungen an der Gattung Drimys. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 87: 1-16.

Larsen L, Lorimer SD, Perry NB. 2007. Contrasting chemistry of fruits and leaves of two Pseudowintera species: sesquiterpene dialdehyde cinnamates and prenylated flavonoids. – Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 35: 286-292.

Lemèsle A. 1950. Persistance de caractères archaïques du bois secondaire chez les Canellacées. – Compt. Rend. Acad. Sci. Paris 231: 455-456.

Lemèsle A. 1951. Nouvelles remarques histologiques et phylogénétiques sur la famille des Canellacées. – Rev. Gén. Bot. 58: 193-202.

Leroy J-F. 1977. A compound ovary with open carpels in Winteraceae (Magnoliales): evolutionary implications. – Science 196: 977-978.

Leroy J-F. 1978. Une sous-famille monotypique de Winteraceae endémique à Madagascar: Takhtajanioideae. – Adansonia, sér. II, 17: 383-395.

Leroy J-F. 1980. Nouvelles remarques sur le genre Takhtajania (Winteraceae-Takhtajanioideae). – Adansonia, sér. II, 20: 9-20.

Lloyd DG, Wells MS. 1992. Reproductive biology of a primitive angiosperm, Pseudowintera colorata (Winteraceae), and the evolution of pollination systems in Anthophyta. – Plant Syst. Evol. 181: 77-95.

Lobreau-Callen D. 1977. Le pollen de Bubbia perrieri R. Cap.: rapports palynologiques avec les autres genres de Wintéracées. – Adansonia, sér. II, 16: 445-460.

Marquinez X, Lohmann LG, Salatino MLF, Salatino A, Gonzalez F. 2009. Generic relationships and dating of lineages in Winteraceae based on nuclear (ITS) and plastid (rps16 and psbA-trnH) sequence data. – Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 53: 435-449.

Morawetz W. 1984. How stable are genomes of tropical woody plants? Porcelia, Annona, Drimys. – Plant Syst. Evol. 145: 29-39.

Müller S, Salomo K, Salazar J, Naumann J, Jaramillo MA, Neinhuis C, Feild TS, Wanke S. 2015. Intercontinental long-distance dispersal of Canellaceae from the New to the Old World revealed by a nuclear single copy gene and chloroplast loci. – Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 84: 205-219.

Nast CG. 1944. The comparative morphology of the Winteraceae VI. Vascular anatomy of the flowering shoot. – J. Arnold Arbor. 25: 454-466.

Norton SA. 1980. Reproductive ecology of Pseudowintera (Winteraceae). – M.Sc. thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

Occhioni P. 1945. O número de cromôsomios em Capsicodendron. – Rodriguesia 9: 37-42.

Occhioni P. 1948a. Contribuição ao estudo da família “Canellaceae”, estudo citológico. – Arq. Jar. Bot. Rio de Janeiro 8: 8-165.

Occhioni P. 1948b. Nota sobre a biología das canellas brasileiras. – Arq. Jard. Bot. Rio de Janeiro 8: 275-279.

Parameswaran N. 1961a. Foliar vascularisation and histology in the Canellaceae. – Proc. Indian Acad. Sci., Sect. B, 54: 306-317.

Parameswaran N. 1961b. Ruminate endosperm in the Canellaceae. – Curr. Sci. 30: 344-345.

Parameswaran N. 1962. Floral morphology and embryology in some taxa of the Canellaceae. – Proc. Indian Acad. Sci., Sect. B, 55: 167-182.

Patel RN. 1974. Wood anatomy of the dicotyledons indigenous to New Zealand 4. Winteraceae. – New Zealand J. Bot. 12: 19-32.

Pellmyr O, Thien LB, Bergström G, Groth I. 1990. Pollination of New Caledonian Winteraceae; opportunistic shifts or parallel radiation with their pollinators? – Plant Syst. Evol. 173: 143-157.

Poole I, Frances JE. 2000. The first record of fossil wood of Winteraceae from the Upper Cretaceous of Antarctica. – Ann. Bot. 85: 307-315.

Praglowski J. 1979. Winteraceae Lindl. – In: Nilsson S (ed), World Pollen and Spore Flora 8, Almqvist & Wiksell, Stockholm.

Prakash N, Lim AL, Sampson FB. 1992. Anther and ovule development in Tasmannia (Winteraceae). – Aust. J. Bot. 40: 877-885.

Rodríguez RA, Quezada M. 1991. New combination in Drimys J. R. et G. Forster (Winteraceae) of Chile. – Gayana Bot. 48: 111-114.

Sage TL, Sampson FB. 2003. Evidence for ovarian self-incompatibility as a cause of self-sterility in the relictual woody angiosperm Pseudowintera axillaris (Winteraceae). – Ann. Bot., N. S., 91: 807-816.

Sage TL, Sampson FB, Bayliss P, Gordon MG, Heij EG. 1998. Self-sterility in the Winteraceae. – In: Owens SJ, Rudall PJ (eds), Reproductive biology in systematics, conservation and economic botany, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, pp. 317-328.

Salazar J. 2006. Systematics of Neotropical Canellaceae. – Ph.D. diss., Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.

Salazar J, Nixon K. 2008. New discoveries in the Canellaceae in the Antilles: how phylogeny can support taxonomy. – Bot. Rev. 74: 103-111.

Sampson FB. 1963. The floral morphology of Pseudowintera, the New Zealand member of the vesselless Winteraceae. – Phytomorphology 13: 403-423.

Sampson FB. 1970. Unusual features of cytokinesis in meiosis of pollen mother cells of Pseudowintera traversii (Buchan.) Dandy (Winteraceae). – Beitr. Biol. Pflanzen 47: 71-77.

Sampson FB. 1974. A new pollen type in the Winteraceae. – Grana 14: 11-15.

Sampson FB. 1975. A new pollen type in the Winteraceae. Correction. – Grana 15: 159.

Sampson FB. 1978. Placentation in Exospermum stipitatum (Winteraceae). – Bot. Gaz. 139: 215-222.

Sampson FB. 1980. Natural hybridism in Pseudowintera (Winteraceae). – New Zealand J. Bot. 18: 43-51.

Sampson FB. 1981. Synchronous versus asynchronous mitosis within permanent pollen tetrads of the Winteraceae. – Grana 20: 19-23.

Sampson FB. 1983. A new species of Zygogynum (Winteraceae). – Blumea 28: 353-360.

Sampson FB. 1987. Stamen venation in the Winteraceae. – Blumea 32: 79-89.

Sampson FB. 2000. The pollen of Takhtajania perrieri (Winteraceae). – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 87: 380-388.

Sampson FB, Kaplan DR. 1970. Origin and development of the terminal carpel of Pseudowintera traversii. – Amer. J. Bot. 57: 1185-1196.

Sampson FB, Tucker SC. 1978. Placentation in Exospermum stipitatum (Winteraceae). – Bot. Gaz. 139: 215-222.

Sampson FB, Williams JB, Woodland PS. 1988. The morphology and taxonomic position of Tasmannia glaucifolia (Winteraceae), a new Australian species. – Aust. J. Bot. 36: 395-413.

Schatz GE. 2000. The rediscovery of a malagasy endemic: Takhtajania perrieri (Winteraceae). – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 87: 297-302.

Schatz GE, Lowry PP II, Ramisamihantanirina A. 1998. Takhtajania perrieri rediscovered. – Nature 391: ix, 133-134.

Schrank E. 2013. New taxa of winteraceous pollen from the Lower Cretaceous of Israel. – Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 195: 19-25.

Smith AC. 1943a. The American species of Drimys. – J. Arnold Arbor. 24: 1-33.

Smith AC. 1943b. Taxonomic notes on the Old World species of Winteraceae. – J. Arnold Arbor. 24: 119-164.

Smith AC. 1969. A reconsideration of the genus Tasmannia (Winteraceae). – Taxon 18: 286-290.

Straka H. 1963. Über die mögliche phylogenetische Bedeutung der Pollenmorphologie der madagascarischen Bubbia perieri R. Cap. (Winteraceae). – Grana Palynol. 4: 355-360.

Strasburger E. 1905. Die Samenanlage von Drimys Winteri und die Endospermbildung bei Angiospermen. – Flora 95: 215-231.

Stuchlick L. 1984. Morfologìa de los granos de pollen de las Chlorantaceae y Canellaceae Cubanas. – Acta Bot. Hung. 30: 321-328.

Suh Y, Thien LB, Zimmer EA. 1992. Nucleotide sequences of the internal transcribed spacers and 5.8S rRNA gene in Canella winterana (Magnoliales: Canellaceae). – Nucl. Acids Res. 20: 6101-6102.

Suh Y, Thien LB, Reeve HE, Zimmer EA. 1993. Molecular evolution and phylogenetic implications of internal transcribed spacer sequences of ribosomal DNA in Winteraceae. – Amer. J. Bot. 80: 1042-1055.

Svoma E. 1998. Studies on the embryology and gynoecium structures in Drimys winteri (Winteraceae) and some Annonaceae. – Plant Syst. Evol. 209: 205-229.

Thien LB. 1980. Patterns of pollination in the primitive angiosperms. – Biotropica 12: 1-13.

Thien LB, Bernhardt P, Gibbs GW, Pellmyr O, Bergström G, Groth I, McPherson G. 1985. The pollination of Zygogynum (Winteraceae) by a moth, Sabatinca (Micropterigidae): an ancient association? – Science 227: 540-543.

Thomas N, Bruhl JJ, Ford A, Weston PH. 2014. Molecular dating of Winteraceae reveals a complex biogeographical history involving both ancient Gondwanan vicariance and long-distance dispersal. – J. Biogeogr. 41: 894-904.

Tieghem P van. 1899. Sur le Canellacées. – J. Bot. (Paris) 13: 266-276.

Tobe H, Sampson B. 2000. Embryology of Takhtajania (Winteraceae) and a summary statement of embryological features for the family. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 87: 389-397.

Tucker SC. 1959. Ontogeny of the inflorescence and the flower in Drimys winteri var. chilensis. – Univ. Calif. Publ. Bot. 30: 257-336.

Tucker SC. 1964. Carpel vascularization of Drimys lanceolata. – Phytomorphology 14: 197-203.

Tucker SC. 1975. Carpellary vasculature and the ovular vascular supply in Drimys. – Amer. J. Bot. 62: 191-197.

Tucker SC, Gifford EM. 1966a. Organogenesis in the carpellate flower of Drimys lanceolata. – Amer. J. Bot. 53: 433-442.

Tucker SC, Gifford EM. 1966b. Carpel development in Drimys lanceolata. – Amer. J. Bot. 53: 671-678.

Uedo K. 1978. Vasculature in the carpels of Belliolum pancheri (Winteraceae). – Acta Phytotaxon. Geobot. 29: 119-125.

Verdcourt B. 1956. Canellaceae. – In: Turrill WB, Milne-Redhead E (eds), Flora of tropical East Africa, Crown Agents for Oversea Governments and Administrations, London, pp. 1-4.

Vink W. 1970. The Winteraceae of the Old World I. Pseudowintera and Drimys, morphology and taxonomy. – Blumea 18: 225-354.

Vink W. 1977. The Winteraceae of the Old World II. Zygogynum, morphology and taxonomy. – Blumea 23: 219-250.

Vink W. 1978. The Winteraceae of the Old World III. Notes on the ovary of Takhtajania. – Blumea 24: 521-525.

Vink W. 1983. The Winteraceae of the Old World IV. The Australian species of Bubbia. – Blumea 28: 311-328.

Vink W. 1985. The Winteraceae of the Old World V. Exospermum links Bubbia to Zygogynum. – Blumea 31: 39-55.

Vink W. 1988. Taxonomy in Winteraceae. – Taxon 37: 691-698.

Vink W. 1993a. 19. Winteraceae. – In: Morat P (ed), Flore de la Nouvelle-Calédonie et Dépendances, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, pp. 90-175.

Vink W. 1993b. Winteraceae. – In: Kubitzki K, Rohwer JG, Bittrich V (eds), The families and genera of vascular plants II. Flowering plants. Dicotyledons. Magnoliid, hamamelid and caryophyllid families, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 630-639.

Vink W. 2003. A new species of Zygogynum (Winteraceae) from New Caledonia. – Blumea 48: 183-186.

Vink W. 2014. the Winteraceae of the Old World VII. Zygogynum in the Solomon Islands (incl. Bougainville). – Blumea 59: 155-162.

Vink W. 2016. The Winteraceae of the Old World. VIII. Some Zygogynum species from New Guinea. – Blumea 61: 41-50.

Walker JW, Brenner GJ, Walker AG. 1983. Winteraceae pollen in the Lower Cretaceous of Israel. Early evidence of a Magnolialean angiosperm family. – Science 220: 1273-1275.

Warburg O. 1895. Winteranaceae (Canellaceae). – In: Engler A, Prantl K (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien III(6), W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 314-319.

Williams EG, Sage TL, Thien LB. 1993. Functional syncarpy by intercarpellary growth of pollen tubes in a primitive apocarpous angiosperm, Illicium floridanum (Illiciaceae). – Amer. J. Bot. 80: 137-142.

Wilson TK. 1960. The comparative morphology of the Canellaceae I. Synopsis of genera and wood anatomy. – Trop. Woods 112: 1-27.

Wilson TK. 1964. The comparative morphology of the Canellaceae III. Pollen. – Bot. Gaz. 125: 192-197.

Wilson TK. 1965. The comparative morphology of the Canellaceae II. Anatomy of the young stem and node. – Amer. J. Bot. 52: 369-378.

Wilson TK. 1966. The comparative morphology of the Canellaceae IV. Floral morphology and conclusions. – Amer. J. Bot. 53: 336-343.

Young DA. 1981. Are the angiosperms primitively vesselless? – Syst. Bot. 6: 313-330.

Zimmer EA, Suh Y, Karol KG. 2012. Phylogenetic placement of a recently described taxon of the genus Pleodendron (Canellaceae). – Phytologia 94: 404-412.