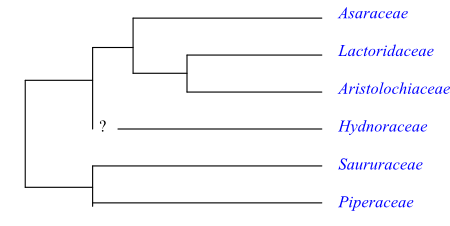

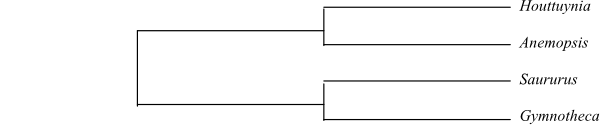

Cladogram of Piperales based on DNA sequence data (mainly Wanke & al. 2007). The sister-group relationship between Saururaceae and Piperaceae has a bootstrap support of 100%.

Piperopsida Bartl., Ord. Nat. Plant.: 78, 83. Sep 1830 [’Piperinae’]; Piperidae Reveal in Phytologia 76: 3. 2 Mai 1994; Piperanae Reveal in Phytologia 76: 3: 2 Mai 1994; Aristolochianae Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.: xxiv. 23 Dec 2001

Fossils Appomattoxia, from the Late Barremian to mid-Albian of Portugal and Virginia, represents fossilized unicarpellate fruits with an orthotropous seed. Monocolpate pollen grains with tectate exine and columellate to granular infratectum are often associated with these fruits, which may be assigned to Piperales.

Habit Usually bisexual, monoecious or dioecious, evergreen trees, shrubs, suffrutices or lianas, perennial or annual herbs. Branches often with articulated stems and more or less swollen nodes. Often aromatic and with peppery taste.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza? Phellogen ab initio superficial or outer-cortical. Primary vascular tissue consisting of scattered bundles or cylinder of bundles (sometimes several concentric cylinders). Secondary lateral growth sometimes anomalous or absent. Cambium and wood sometimes storied. Vessel elements arranged in radial rows. Vessel restriction patterns occurring. Vessel elements with scalariform or simple perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, scalariform or opposite, simple or bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids, fibre tracheids or libriform fibres with simple or bordered pits, septate or non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma usually paratracheal scanty vasicentric, scalariform, reticulate, or banded (sometimes apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates). Sieve tube plastids P2c, Pc, Pcs, Psc, Pcs(f), S or S0 type (some Piperales have monocotyledon type cuneate sieve tube plastids). Nodes ≥3:≥3, trilacunar or multilacunar with three or more leaf traces (rarely 1:2, unilacunar with two traces). Mucilage canals abundant. Idioblasts with ethereal oils often frequent. Silica often abundant in cell walls. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals often frequent. Druses or rhomboidal crystals sometimes abundant.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate, simple; glandular hairs (including pearl glands) present.

Leaves Alternate (usually distichous) or opposite (rarely verticillate), simple, usually entire (rarely lobed or absent), with conduplicate or involute (sometimes supervolute) ptyxis. Stipules intrapetiolar, free or adnate to petiole or modified in various ways, or absent; leaf sheath usually absent (petiole sometimes sheathing). Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate, annular or inwardly U-shaped. Venation pinnate, brochidodromous, eucamptodromous, campylodromous, and/or palmate, acrodromous or actinodromous. Stomata usually anomocytic or tetracytic (sometimes cyclocytic or helicocytic, rarely absent). Cuticular wax crystalloids as parallel platelets or transversely ridged annular rodlets (transversely ridged Aristolochia type crystalloids), or absent, chemically characterized by presence of palmitone (hentriacontan-16-one) and absence of nonacosan-10-ol. Lamina often gland-dotted. Mesophyll and epidermis often with idioblasts containing ethereal oils. Mesophyll cells sometimes with druses. Epidermal and/or palisade cells often with silica bodies. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal, axillary or leaf-opposite spike or spadix (sometimes umbellate, rarely raceme), or flowers terminal or axillary, solitary or few together in rhipidia. Floral prophyll (bracteole) single, median, adaxial, or absent.

Flowers Usually zygomorphic (sometimes actinomorphic). Hypogyny or epigyny (rarely half epigyny). Tepals usually in one whorl (sometimes two whorls), with usually valvate (sometimes valvate-induplicate) aestivation, usually connate, unilabiate to multilobate or entire (tepals rarely two to five, sepaloid, connate only at base), or absent. Nectary absent, or present inside perianth tube. Disc epigynous or absent.

Androecium Stamens (one or) two to ten or 6+6 (to more than 40), usually in one or several whorls. Filaments free or partially or entirely connate (often in groups) and/or adnate to pistil into synandrium or gynostemium, or adnate at base to ovary; usually free from tepals (rarely adnate to hypanthium). Anthers usually basifixed, non-versatile, free or dorsally adnate to style, disporangiate or tetrasporangiate, latrorse or extrorse (rarely introrse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory. Staminodia usually absent (rarely three to five, intrastaminal, alternating with fertile stamens).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis usually simultaneous (sometimes successive). Pollen grains usually inaperturate or monosulcate (sometimes polyporate, rarely polycolpate, disulcate, trisulcate or trichotomosulcate), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine usually tectate (rarely semitectate), with usually columellate (rarely intermediary) infratectum, microperforate to reticulate, verrucate, spinulate or psilate (rarely microstriate).

Gynoecium Pistil composed of one or (two or) three to six incompletely or entirely connate carpels; carpel usually plicate (rarely conduplicate), postgenitally entirely fused, without canal. Ovary superior or inferior (rarely semi-inferior), unilocular to multilocular. Stylodia free or connate into trilobate to sexalobate style, or style single, simple, or absent. Stigma single, terminal, lateral or on surface of stylar lobes, usually commissural, or stigmas two to five, capitate or lobate (rarely decurrent), papillate or non-papillate, usually Dry (sometimes Wet) type. Male flowers sometimes with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation basal to subbasal (rarely laminar-lateral), axile (when ovary multilocular) or parietal (when ovary unilocular). Ovules one per ovary, or (one to) numerous per carpel, usually anatropous or orthotropous (rarely hemianatropous), ascending, horizontal or pendulous, apotropous, unitegmic or bitegmic, crassinucellar or tenuinucellar. Micropyle bistomal (often Z-shaped) or endostomal. Inner integument usually thicker than outer integument. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type, or tetrasporous, usually Fritillaria type or Peperomia type (rarely Drusa type, Adoxa type, disporous, Allium type, or 16-nucleate, Penaea type). Antipodal cells often proliferating. Endosperm development ab initio cellular or nuclear. Endosperm haustorium usually absent (sometimes chalazal). Embryogenesis usually piperad (sometimes asterad, rarely solanad).

Fruit Usually a berry, a drupe, or a septicidal and loculicidal capsule (rarely a nut, an assemblage of single-seeded nuts, an irregularly dehiscent capsule, an assemblage of follicles, or a schizocarp).

Seeds Aril absent. Funicular elaiosome sometimes present. Seed coat testal-tegmic or tegmic. Testa often multiplicative. Exotestal cells often enlarged and with thickened walls. Endotesta often palisade, usually with cells containing large single or paired calciumoxalate crystals. Exotegmen often fibrous to sclerotic, often with heavily thickened cell walls. Endotegmen often with reticulate thickenings and tannins. Perisperm copious, with starch, enclosing endosperm and embryo, or not developed. Endosperm copious, fleshy, oily (sometimes also with compound starch grains, rarely ruminate), or scarce. Embryo small, usually little differentiated (rarely undifferentiated), without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology x = 4–9, 11–13, 19

DNA Nuclear gene PHYE absent (lost).

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), catechins, cyanidin, monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes (e.g. γ-elemene), allyl- and propenylphenols, phenylpropanes, tannins, proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins?), aporphine alkaloids, aporphine derivatives, isoquinoline alkaloids (benzylisoquinoline alkaloids, liriodenine), valine and isoleucine derived cyanogenic compounds, cyanogenic glycosides (dhurrin), α-pyrones, myristicin, lignans (veraguensin, austrobailignan, dihydrocubebin), lignans, neolignans, lignoids, ethereal oils, phenanthrenes, aristolochic acids, pinitol, kadsurin A, galbacin, licarin A, naphthoquinones, cinnamoylamides, and asarone present. Inulin rare. Ellagic acid not found.

Systematics The herbaceous habit is probably a plesiomorphy in Piperales. The sympodial architecture of Asaraceae, Piperaceae and Saururaceae is unusual.

The sister-group relationship [Piperaceae+Saururaceae] is usually very strongly supported. Among potential synapomorphies listed by Stevens (2001 onwards) are the following: root epidermis formed from the inner root cap layer; sheathing leaf base; ptyxis supervolute; stomata often tetracytic; terminal inflorescence spicate to spadix-like; minute and strongly reduced flowers lacking tepals; filaments fairly thin; microsporogenesis simultaneous; pollen grains less than 20 μm in diameter; papillate Dry type stigma; ovules orthotropous; seed coat exo/endotegmic; presence of a starchy perisperm; endosperm scanty; and embryo short and broad.

The aristolochioid clade (Piperales minus the [Piperaceae+Saururaceae] clade) share connate and often valvate tepals, extrorse stamens and an often undifferentiated embryo. Aristolochiaceae are, according to some matK analyses, paraphyletic relative to Lactoridaceae and Hydnoraceae, to groups which in that case must be included in Aristolochiaceae. The sister-group relationship [Hydnoraceae+Aristolochiaceae] has weak support, although Hydnoraceae and Aristolochiaceae have the following characters in common: perianth uniseriate, with three connate tepals, with outer tepals valvate; anthers extrorse and almost or completely sessile; ovary inferior; and an undifferentiated embryo. Furthermore, both Hydnoraceae and some species of Aristolochia have successive microsporogenesis. However, at the moment the deeper branching of the Piperales tree is unresolved.

According to Stevens (2001 onwards) the clade [Asaraceae+[Lactoridaceae+ Aristolochiaceae]] is characterized by the following synapomorphies: stomata anomocytic; leaves cordate, with conduplicate ptyxis; venation palmate; floral prophyll (bracteole) adaxial; inflorescences cymose; tepals three, with odd tepal adaxial; androecium trimerous; filaments almost or completely absent; connective extended at apex; carpels free at base; fruit a follicle; endotesta palisade, crystalliferous; exotegmen and inner layers with cruciate fibres; endotegmen with reticulate cell wall thickenings.

|

Cladogram of Piperales based on DNA sequence data (mainly Wanke & al. 2007). The sister-group relationship between Saururaceae and Piperaceae has a bootstrap support of 100%. |

ARISTOLOCHIACEAE Juss. |

( Back to Piperales ) |

Aristolochiales Juss. ex Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 270. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Aristolochiae’]; Aristolochiopsida Bartl. Ord. Nat. Pl.: 78, 79. Sep 1830 [’Aristolochieae’]; Pistolochiaceae J. B. Müll., Fl. Waldecc. Itter.: 121. 1841 [‘Paistolochinae’], nom. illeg.

Genera/species 1/480–500

Distribution Tropical, subtropical and temperate Eurasia, Africa and America, and Australasia to northern Australia.

Fossils Leaf impressions, Aristolochites kamchaticus, from the Early Santonian of Kamchatka, have been compared to leaves in extant Aristolochiaceae, and Cenozoic leaves from Georgia, Ukraine, Poland and North America may be attributed to Aristolochia. Aristolochioxylon comprises wood from the Late Cretaceous and Early Cenozoic Deccan Intertrappean Beds of India. Aristolochiacidites comprises pollen grains assigned to Aristolochiaceae and was described from the Campanian/Maastrichtian border in the Vilui Basin, Siberia.

Habit Usually bisexual (rarely unisexual), usually perennial herbs with monopodial growth (usually scrambling or climbing; sometimes suffrutices, shrubs or lianas, e.g. Aristolochia arborea); branches often with somewhat swollen nodes. Hypocotyledonary tuber often present.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio superficial. Primary vascular tissue consisting of a cylinder of vascular bundles. Cambium and wood more or less storied. Secondary lateral growth sometimes deformed by strongly expanded medulla and primary medullary rays. Endodermis prominent. Vessel elements with simple perforation plates; lateral pits alternate or opposite, simple or bordered pits. Vessel restriction patterns present. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids or tracheids with simple or bordered pits, septate or non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, heterocellular (in lianas interfascicular, very wide and tall, subdividing vascular tissue into separate vascular bundles). Axial parenchyma usually paratracheal, scalariform, reticulate, or banded (sometimes apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates). Sieve tube plastids usually different variations of P type: in some species Pc type with a single cuneate proteine crystalloid, but without starch; in other species Pcs type with a polygonal protein crystalloid and few starch grains; in certain species Psc type with a single polygonal protein crystalloid and approx. ten starch grains; in several species Pcs(f) type with a single polygonal protein crystalloid, protein filaments and few starch grains; in other species (species within the “Thottea clade”) S type with approx. 15 globular starch grains of different size surrounded by a membrane. Nodes 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces. Cells containing silica in walls often abundant. Druses common (e.g. in wood rays).

Trichomes Hairs uniseriate, often with uncinate terminal cell (hooked); glandular hairs present.

Leaves Alternate (distichous), simple, usually entire (in some species of Aristolochia laciniate), with conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole with a ring of three vascular bundles, or vascular bundles U-shaped. Venation usually palmate (sometimes pinnate). Stomata usually anomocytic. Lamina sometimes gland-dotted. Cuticular wax crystalloids as transversely ridged annular rodlets (Aristolochia type), chemically dominated by palmitone, or absent. Mesophyll and epidermis often with idioblasts containing ethereal oils. Epidermal and/or palisade cells often with silica bodies. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Flowers terminal or axillary, solitary or few together in rhipidia. Floral prophyll (bracteole) usually single, median, adaxial (rarely? paired, lateral).

Flowers Zygomorphic (sometimes resupinate), often large, frequently with a foul smell. Epigyny. Tepals usually in one whorl, with usually valvate (sometimes valvate-induplicate) aestivation; tepals usually connate (bell-, urn-, tube-, pitcher-, pipe- or S-shaped), unilabiate to multilobate or entire; median outer tepal usually adaxial. Coarse hairs directed downwards often present inside perianth tube and withering after pollination. Perianth tube with nectaries or secretory hairs. Disc epigynous or absent.

Androecium Stamens (three to) six or 6+6 (to more than 40 in “Thottea clade”), usually in one (representing inner whorl) or two (in some species three or four) whorls. Filaments short, thick, free or partially or entirely connate into synandrium or in groups of three and/or adnate to pistil into gynostemium; usually free from tepals. Anthers usually basifixed, non-versatile, free or dorsally adnate to style, tetrasporangiate, extrorse or in outer staminal whorl almost latrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory, with multinucleate cells. Staminodia usually absent. Secondary pollen display present in some species.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis usually simultaneous (sometimes successive). Pollen grains usually inaperturate or monosulcate (sometimes polyporate, rarely polycolpate), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with usually columellate infratectum, microperforate or reticulate, verrucate or psilate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (three or) four to six usually connate and apically constricted carpels; carpel plicate, postgenitally completely fused, without canal; internal compitum present. Ovary inferior, unilocular or quadrilocular to sexalocular (sometimes incompletely so due to imperfectly intrusive septa). Stylodia free or connate into (tri- or) quadri- to sexalobate style. Stigma terminal, lateral or on surface of stylar lobes, usually commissural, papillate(-hairy), Dry or Wet type. Male flowers occasionally with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation axile (when ovary multilocular) or parietal (when ovary unilocular). Ovules (four to) c. 20 to more than 50 per carpel, anatropous, pendulous to horizontal, apotropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal. Outer integument two cell layers thick. Inner integument two or three cell layers thick. Megagametophyte usually monosporous, Polygonum type (of several variants). Hypostase usually present. Endosperm development cellular. Embryogenesis?

Fruit Usually a septicidal and loculicidal capsule (rarely a nut or an assemblage of one-seeded nuts, possibly a schizocarp with follicle-like mericarps); in certain species a dry berry, in other species a schizocarp.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat testal-tegmic. Testa multiplicative. Exotestal cells (inner epidermis of outer integument) often enlarged and with thickened walls. Endotesta palisade, usually with cells containing large single or paired calciumoxalate crystals; endotestal cells often lignified. Exotegmen usually fibrous to sclerotic. Endotegmen usually with reticulate thickenings (three layers of fibres crossing each other at right angles) and tannins. Perisperm usually not developed. Endosperm copious, fleshy, oily (sometimes also starchy), sometimes (the “Thottea clade”) ruminate. Embryo small, usually little differentiated (sometimes undifferentiated), without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology x = (4–)6–7(–8 or more)

DNA The nuclear gene PHYE is absent.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), catechins, mono- and sesquiterpenes (e.g. γ-elemene), aporphine alkaloids, benzylisoquinoline alkaloids, protoberberines (berberine), dimeric tetrahydrobenzyl alkaloids, lignans of furofuran and dibenzyl-α-lactol types, neolignans of benzofuranoid type, phenanthrenes (substituted by lactam and lactone units etc.), and aristolochic acid present. Allyl- and propenylphenols rare. Inulin present. Ellagic acid and proanthocyanidins not found.

Use Ornamental plants, medicinal plants.

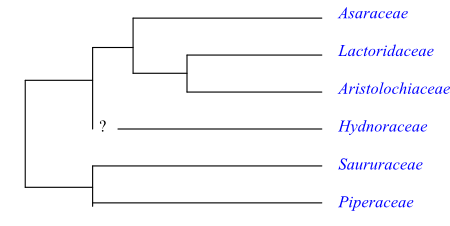

Systematics Aristolochia (480–500; Europe, the Mediterranean, tropical, subtropical and temperate Africa and Asia and southwards to northern Australia, North to South America). – Six or eight main clades are distinguishable within Aristolochia (González & Stevenson 2002; Kelly & González 2003; etc.).

Aristolochiaceae appear to be sister-group to Lactoris (Lactoridaceae), although some analyses show a relatively high support for Aristolochiaceae being sister-group to Hydnoraceae. Sometimes Lactoris is sister to Hydnoraceae and nested inside Aristolochiaceae (e.g. Nickrent & al. 2002). However, the basal phylogeny within the aristolochioid clade is far from clarified.

The twining and climbing habit is a plesiomorphy in Aristolochiaceae and a few species are even lianas.

|

Single most parsimonious cladogram of Aristolochia sensu lato based on morphology (Kelly & González 2003). |

ASARACEAE Vent. |

( Back to Piperales ) |

Asarales Horan., Char. Ess. Fam.: 68. 30 Jun 1847 [’Asarastra’]; Asaropsida Horan., Prim. Lin. Syst. Nat.: 57. 2 Nov 1834 [’Asaroideae’]; Sarumaceae Nakai, Fl. Sylv. Koreana 21: 17. 1936 [‘Sarumataceae‘]

Genera/species 2/c 85

Distribution Northern temperate regions, with their largest diversity in East Asia.

Fossils Asarum circularis has been described from the Oligocene of Oregon.

Habit Bisexual, perennial herbs with sympodial growth.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio superficial. Primary vascular tissue cylinder of vascular bundles. Vessel elements with simple perforation plates; lateral pits alternate or opposite, simple or bordered pits. Vessel restriction patterns present. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids or tracheids with simple or bordered pits, septate or non-septate. Wood rays absent? Axial parenchyma usually paratracheal, scalariform, reticulate, or banded. Sieve tube plastids P2c type with cuneate protein crystalloids and a single large polygonal crystal, without starch. Endodermis prominent. Nodes usually 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces (in Saruma 3:2, with two traces from central leaf gap).

Trichomes Hairs uniseriate; glandular hairs present.

Leaves Alternate (distichous), simple, usually entire, with conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole with ring of (three) vascular bundles, or vascular bundles U-shaped. Venation usually palmate (sometimes pinnate). Stomata usually anomocytic. Lamina sometimes gland-dotted. Cuticular wax crystalloids as transversely ridged annular rodlets chemically dominated by palmitone. Mesophyll and epidermis often with idioblasts containing ethereal oils. Epidermal and/or palisade cells often with silica bodies. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Flowers solitary terminal. Floral prophyll (bracteole) single, median, adaxial.

Flowers Actinomorphic. Hypanthium present. Half epigyny to almost hypogyny. Outer (sepaloid) and inner (petaloid) perianth whorls distinct. Perianth in Asarum uniseriate, with three petaloid usually free tepals (in Asarum caulescens slightly connate at base), with imbricate aestivation; inner perianth whorl usually absent (rarely minute and staminodial). Perianth in Saruma biseriate, with three outer sepaloid and three inner petaloid free clawed tepals, with valvate aestivation; inner tepals with development retarded relative to other floral parts. Nectary and disc absent.

Androecium Stamens six or 6+6. Filaments short, thick, free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, free or dorsally adnate to style, tetrasporangiate, extrorse or in outer staminal whorl almost latrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory, with multinucleate cells. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually monosulcate (sometimes inaperturate; occasionally polyporate or polycolpate; in Saruma sometimes triporate), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine usually tectate (in Saruma semitectate), with columellate infratectum, microperforate (in Saruma reticulate), verrucate or psilate.

Gynoecium Pistil in Asarum composed of usually three to six connate carpels, in Saruma composed of nine, almost free carpels, adnate to hypanthium; carpel plicate, postgenitally completely fused, without canal; internal compitum present. Ovary semi-inferior to almost superior, unilocular or quadrilocular to sexalocular. Stylodia free or connate into a trilobate to sexalobate style. Stigma terminal, lateral or on surface of stylar lobes, usually commissural, with multicellular papillae, at least usually Dry type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation axile (when ovary multilocular) or parietal (when ovary unilocular). Ovules (four to) numerous (c. 20 to more than 50) per carpel, anatropous, pendulous to horizontal, apotropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle usually endostomal (in Saruma sometimes bistomal). Outer integument two cell layers thick. Inner integument three cell layers thick. Megagametophyte usually monosporous, Polygonum type. Hypostase usually present. Endosperm development cellular. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit Usually a septicidal and loculicidal capsule (in some species of Asarum an irregularly dehiscent capsule; in Saruma an assemblage of follicles with with persistent outer (sepaloid) tepals, possibly a schizocarp with follicle-like mericarps).

Seeds Aril absent. Elaiosome sometimes present. Funicular elaiosome reaching along raphe. Seed coat tegmic. Testal cells except inner epidermal cells unspecialized. Exotegmen fibrous to sclerotic. Endotegmen with reticulate thickenings (three layers of fibres crossing each other at right angles), tanniniferous. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, fleshy, oily. Embryo small, usually little differentiated, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = (6) 12, 13, 18, 20, 26. – Chromosomes in Asarum large.

DNA Nuclear gene PHYE absent (lost). AP3 expression localised on tepal edges. The entire SSC region or a substantial part of it is incorporated into the IR in several species of Asarum (Sinn & al. 2018).

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), catechins, mono- and sesquiterpenes, allyl- and propenylphenols (frequent), lignoids (abundant), and asarone present. Ellagic acid and proanthocyanidins not found.

Use Ornamental plants, medicinal plants.

Systematics Asarum (c 84; temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere), Saruma (1; S. henryi; northwestern to southwestern China).

The chromosomes in Asarum are often large and resemble monocot chromosomes. In Saruma, on the other hand, the chromosomes are minute and similar to Aristolochiaceae.

Asaraceae are sister to [Lactoridaceae+Aristolochiaceae] with low to moderate support.

Asaraceae and Aristolochiaceae have largely different types of mono- and sesquiterpenes.

HYDNORACEAE C. Agardh |

( Back to Piperales ) |

Hydnoroideae Walp., Ann. Bot. Syst. 3: 513. 24-25 Aug 1852 [‘Hydnoreae’]; Hydnorales Takht. ex Reveal in Novon 2: 239. 13 Oct 1992

Genera/species 2/10

Distribution Tropical and southern Africa, Madagascar, the Arabian Peninsula, Réunion, Costa Rica, Peru, Argentina.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bixexual, herbaceous achlorophyllous endophytic root holoparasites mainly on Fabaceae (in, e.g., Acacia and Prosopis) and Euphorbiaceae.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza absent. Phellogen ab initio superficial. Stout earth-penetrating root-like rhizome – formerly called “pilot root” – with unlimited growth and at apex with thickened root-cap-like structure enclosing an apical meristem of a vegetative shoot. Scattered procambial vascular strands arising from apical meristem and developing into several endarch separate collateral (scattered) bundles radially arranged around medulla. Interfascicular cambium and secondary lateral growth absent. Fascicular cambia present. Vessels with simple perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform. Periderm continuous. Small thin unbranched partially nutrient- and water-sucking lateral haustorial roots containing meristems and with limited growth, branching and provided with haustoria, from which hypha-like cell threads invade host, arising exogenously from surface of root-like rhizome and parasitizing stele of host roots. Root-like rhizome with parenchymatic tissue containing tanniniferous mucilage cells (sometimes lysigenous mucilage canals or cavities with catechin. Stele atactostele-like. Sieve tube plastids S0 type without protein crystalloids, protein filaments or starch grains (i.e. without any distinct content). Crystals?

Trichomes Hairs uniseriate; glandular hairs present.

Leaves Absent. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Stomata abnormous. Cuticular waxes absent.

Inflorescence Flowers solitary, endogenously arising from pilot roots. Prophyll single, median, adaxial.

Flowers Actinomorphic, large, partially subterranean, frequently with evil odour, large, endogenously arising from “pilot roots”, usually trimerous or tetramerous (rarely pentamerous). Hypanthium short. Epigyny. Perianth one-whorled. Tepals usually three or four (rarely two or five), with valvate aestivation, sepaloid, thick, fleshy, connate at base. Corolla tube with nectaries or secretory hairs. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens usually three or four (rarely five), in one whorl, haplostemonous, antetepalous (or six, eight or ten). Filaments short, thick, free or partially or entirely connate into synandrium or in groups of three and/or adnate to pistil into gynostemium; adnate to hypanthium. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, connate into annular synandrium, polythecate; connective often apically prolonged and co-operating with gynostemium at pollination; anthers and filaments in Prosopanche connate into a dome with central orifice, tetrasporangiate, extrorse or in outer staminal whorl almost latrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory, with multinucleate cells. Staminodia in Hydnora absent or in Prosopanche three to five, intrastaminal (below fertile stamens), fleshy, alternating with tepals.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive (tetrads tetragonal). Pollen grains in Hydnora monosulcate, in Prosopanche disulcate, trisulcate or trichotomosulcate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with usually columellate infratectum, microperforate or reticulate, verrucate or psilate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of three (or four) alternitepalous usually connate carpels; carpel plicate, postgenitally completely fused, without canal; internal compitum present. Ovary inferior, unilocular or quadrilocular to sexalocular (often seemingly multilocular due to intrusion of placentae; sometimes incompletely locular due to imperfectly intrusive septa). Style absent. Stigma widely cushion-shaped, papillate, Dry type, in Hydnora usually trilobate (lamellae parietal), in Prosopanche formed by somewhat protruding apices of placental lamellae.

Ovules Placentation in Prosopanche parietal (lamellar placentae in three parietal groups covered by ovules, deeply intrusive yet not fused in middle), in Hydnora apical-subapical, pendulous (placental lamellae numerous, branched, arising from ovary apex). Ovules numerous per carpel (up to c. 35.000 per flower), orthotropous, pendulous to horizontal, apotropous, in Hydnora unitegmic, integument in Prosopanche micropylar and not distinctly delimited from placenta, incompletely tenuinucellar, with meiocyte hypodermal at apex of megasporangium. Micropyle endostomal. Outer integument two cell layers thick. Inner integument two or three cell layers thick. Megasporangial epidermis persistent. Nucellar cap? Parietal cells absent. Megagametophyte in Hydnora tetrasporous, Adoxa type; in Prosopanche disporous, Allium type. Hypostase usually present. Endosperm development cellular. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis variation of solanad (proembryo comprising a linear row of c. 15 cells before first vertical wall is laid down).

Fruit In Hydnora fleshy, baccate, with coriaceous exocarp, usually hypogeal; in Prosopanche a pyxidium (dehiscing by lid).

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat testal-tegmic. Exotestal cells usually with thickened inner walls. Exotegmen usually fibrous to sclerotic. Endotegmen usually with reticulate thickenings (three layers of fibres crossing each other at right angles) and tannins. Perisperm thin, one-layered. Endosperm copious, fleshy, oily; endosperm cells with thick walls, with arabinose and starch. Embryo minute, undifferentiated or little differentiated, without chlorophyll. Suspensor in Hydnora long, in Prosopanche short. Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar? Germination via germination tube.

Cytology n = ?

DNA Nuclear gene PHYE absent (lost). Plastome of Hydnora highly reduced with numerous plastid genes lost.

Phytochemistry Very insufficiently known. Condensed tannins (high amounts) present.

Use Ornamental plants, medicinal plants.

Systematics Hydnora (6; H. abyssinica, H. africana, H. esculenta, H. sinandevu, H. triceps, H. visseri; arid and semiarid regions in tropical and southern Africa, Madagascar, Réunion, southwestern Arabian Peninsula), Prosopanche (4; P. americana, P. bonacinae, P. caatingicola, P. costaricensis; Costa Rica, Peru, northeastern and southern Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina).

Some analyses using both mitochondrial and nuclear genes show a relatively high support for Hydnoraceae being sister-group to Aristolochiaceae (e.g. Nickrent & al. 2002), and epigyny, connate valvate tepals, extrorse anthers, and successive microsporogenesis also indicate a close relationship. On the other hand, Hydnoraceae is sometimes recovered as sister to Lactoris and nested inside Aristolochiaceae (Nickrent & al. 2002). However, the phylogeny within Aristolochiaceae s.lat. is not clarified.

LACTORIDACEAE Engl. |

( Back to Piperales ) |

Lactoridales Takht. ex Reveal in Phytologia 74: 174. 25 Mar 1993; Lactoridanae Takht. ex Reveal et Doweld in Novon 9: 550. 30 Dec 1999

Genera/species 1/1

Distribution Juan Fernández.

Fossils Fossil pollen tetrads, Lactoripollenites africanus, which may be assigned to Lactoris, have been found in Turonian to Campanian layers off the Southwest African coast. Lactoripollenites has been recorded in Campanian to Oligocene sediments in Australia. Fossil pollen assigned to Lactoridaceae have also been found in India, North America, the Antarctic Peninsula, and in Early Miocene layers in eastern Patagonia in southern South America.

Habit Bisexual, gynomonoecious or polygamodioecious, evergreen shrub.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen superficial? Primary vascular tissue cylinder of vascular bundles. Cambium and wood storied? Vessel elements with simple perforation plates; lateral pits usually alternate (rarely scalariform or opposite). Wood, fibres and axial parenchyma storied. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform fibres or fibre tracheids with rudimentary bordered pits. Wood rays wide and tall, absent from internodes in young stems. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse, scanty, vasicentric. Sieve tube plastids S type, with approx. ten spherical starch grains. Nodes 1:2, unilacunar with two leaf traces; nodes swollen due to thicker medulla and cortex in nodes than in internodes. Cortex with idioblasts containing ethereal oils (camphor oil, coumaric acid). Calciumoxalate crystals?

Trichomes Hairs absent.

Leaves Alternate (distichous), simple, entire, with conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules intrapetiolar, connate and adnate to adaxial side of petiole, and forming an ochrea-like leaf sheath around stem. Petiole vascular bundle transection? Venation almost pinnate. Stomata anomocytic. Lamina gland-dotted. Cuticular wax crystalloids as parallel platelets (Convallaria type). Mesophyll and epidermis often with idioblasts containing ethereal oils. Epidermal and/or palisade cells often with silica bodies. Leaf margin entire. Leaf apex emarginate.

Inflorescence Flowers usually two to four together in axillary cymose (thyrsoid) inflorescence (sometimes solitary axillary). Floral prophyll (bracteole) single median adaxial at base of pedicel, or absent.

Flowers Actinomorphic. Hypogyny. Tepals three, whorled, with imbricate aestivation, sepaloid, free; median outer tepal usually adaxial. Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens 3+3, diplostemonous. Filaments short, relatively wide, free from each other and from tepals, or absent. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, extrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective somewhat prolonged. Tapetum secretory? Female flowers with inner or both staminal whorls staminodial.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive? Pollen grains monosulcate (anasulcate or ulcerate) with diffusely delimited aperture, saccate, shed as tetrads, bicellular? at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum, perforate to scabrate.

Gynoecium Carpels three, whorled, connate only at base, alternitepalous; carpel plicate, postgenitally completely fused, without canal; internal compitum present. Ovary inferior, unilocular (apocarpy). Stylodia short. Stigmas decurrent, papillate?, Dry type? Male flowers with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation marginal, intrusive. Ovules four to eight per carpel, anatropous, bitegmic, incompletely tenuinucellar or weakly crassinucellar. Funicle long, running along carpellary margins. Micropyle ?-stomal, erect. Outer integument ? cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Hypostase? Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustorium chalazal. Embryogenesis?

Fruit Fruits an assemblage of follicles, slightly connate at base.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat testal-tegmic. Testal cells collapsed, with two persistent cuticular layers. Tegmen? Perisperm? Endosperm copious, oily. Embryo small, well differentiated, without? chlorophyll. Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar?

Cytology n = 20, 21 (palaeotetraploid?).

DNA Nuclear gene PHYE absent (lost).

Phytochemistry Virtually unknown. Flavonoids consisting of 6,3-O-diglycosides of kaempferol and isorhamnetin present.

Use Ornamental plants, medicinal plants.

Systematics Lactoris (1; L. fernandeziana; Masatierra [Robinson Crusoe Island] in Juan Fernandez).

Lactoris is sister to Aristolochiaceae. Monopodial growth and distinct bracts are characters shared by these two clades, according to Stevens (2001 onwards). Sometimes Lactoris has been recovered as sister to Hydnoraceae and nested inside Aristolochiaceae (see, e.g., Nickrent & al. 2002). However, the phylogeny within Aristolochiaceae sensu lato is not clarified.

Lactoridaceae had a much wider distribution during the Late Cretaceous and the Early Cenozoic, and the extant distribution of Lactoris fernandeziana is relictual. Provided the pollen fossil from North America, the Antarctic Peninsula, South Africa, India and Australia (e.g. Macphail & al. 1999) are correctly assigned, Lactoridaceae appear to have had an almost worldwide distribution. Gamerro & Barreda (2008) postulated that the group originated in South Africa during the Cretaceous, expanded and reached its maximum during the Maastrichtian. The migration to South America may have taken place either from Africa or via Antarctica. The decline from the Miocene onwards may have depended on the expansion of more arid climate and the elimination of moist forests. The occurrence in the Juan Fernandez islands may be due to long-distance dispersal (possibly by birds), and may have taken place at some moment during the last 4 My (the Pliocene).

PIPERACEAE Giseke |

( Back to Piperales ) |

Peperomiaceae A. C. Sm., Fl. Vit. Nova 2: 75. 26 Oct 1981; Piperineae Shipunov in A. Shipunov et J. L. Reveal, Phytotaxa 16: 64. 4 Feb 2011

Genera/species 5/>2.600

Distribution Central Africa to Madagascar, southern India and Sri Lanka, southern China to East Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand, islands in the Pacific, Central America and the West Indies to Argentina.

Fossils Fossilized seeds of Peperomia have been described from Cenozoic layers in Europe and Siberia.

Habit Bisexual, monoecious or dioecious, evergreen trees, shrubs or lianas, erect or climbing, usually perennial (in Peperomia sometimes annual) herbs (Peperomia often epiphytes), often succulent, often with articulated stems and swollen nodes. Aromatic and with sharp (peppery) taste. CAM physiology present in many species of Peperomia.

Vegetative anatomy Root epidermis developing from inner root cap layer. Phellogen ab initio outer cortical. Primary vascular bundles scattered in stem (atactostele) or as several concentric? cylinders (outer one – leaf – cylindrically fused, inner one as one or two vascular cylinders). Leaf traces usually remaining in transit through two or more internodes. Medullary vascular bundles present. Vascular bundles open, not enclosed within sclerenchymatous envelope. Cambium storied or absent. Wood often storied. Secondary lateral growth sometimes anomalous (in Peperomia often absent). Vessel elements with scalariform or simple perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, scalariform or opposite, simple and/or bordered pits. Vessel restriction patterns present. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids, tracheids or libriform fibres with simple pits, septate or non-septate. Wood rays multiseriate (wide and tall), heterocellular. Axial parenchyma paratracheal scanty vasicentric. Tyloses sometimes abundant. Sieve tube plastids usually S type, with approx. ten starch grains (sometimes S0 type, without starch or protein). Endodermis in Piper very variable. Nodes ≥3:≥3, trilacunar to multilacunar with three or more leaf traces. Mucilage canals abundant. Idioblasts with ethereal oils. Silica often abundant in leaves. Calciumoxalate druses and raphides often abundant (especially in leaves).

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, simple; pearl glands sometimes present.

Leaves Alternate (spiral or distichous) or opposite (in some species of Peperomia verticillate), simple, usually entire (rarely lobed), often fleshy, with usually involute (sometimes supervolute) ptyxis. Stipule-like structures intrapetiolar, free or adnate to petiole or in different ways transformed, or absent; petiole often sheathing, usually winged (in Peperomia without wings). Ligule present or absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate. Venation pinnate, brochidodromous, eucamptodromous or campylodromous, and/or palmate, acrodromous or actinodromous. Stomata usually tetracytic or anomocytic (sometimes cyclocytic or helicocytic), often surrounded by a whorl of subsidiary cells. Cuticular wax crystalloids absent. Lamina often gland-dotted. Mesophyll with idioblasts containing ethereal oils. Hydathodes usually abundant. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal, axillary or leaf-opposite, spikes or spadices (sometimes umbel-like; in two species of Peperomia epiphyllous). Bract peltate, clavate, orbiculate or laterally inserted. Floral prophyll (bracteole) single, basal, median adaxial to lateral, paired and lateral, or absent.

Flowers Zygomorphic, small or very small. Hypogyny. Tepals absent. Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens usually two, three, 3+3 or seven (rarely one, or eight to ten; stamens in Peperomia two), whorled. Filaments free or connate at base, often adnate at base to ovary. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (in Peperomia disporangiate, finally with fused locules), latrorse (to extrorse?), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory. Staminodia present or absent (in Peperomia absent).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually monosulcate (in Verhuellia and Peperomia inaperturate, very small), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate to granular infratectum, microperforate, often spinulate or echinulate, sometimes punctuate(-papillate). Endexine absent or very thin.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (two or) three or four (or five) incompletely connate carpels (in Peperomia one carpel); carpel ascidiate, postgenitally entirely fused, without canal; internal compitum present. Ovary superior, unilocular (in Peperomia monomerous). Style single, simple, usually very short, or absent. Stigma single or stigmas (two or) three or four (or five), usually terminal (sometimes lateral; stigma in Peperomia often penicillate), capitate or lobate, usually papillate (in Peperomia non-papillate), Dry type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation basal or subbasal. Ovule one per ovary, orthotropous, ascending, usually bitegmic (in Verhuellia and Peperomia unitegmic), crassinucellar or tenuinucellar (Peperomia). Micropyle usually endostomal (in Zippelia and some species of Piper bistomal). Outer integument three to five cell layers thick. Inner integument three to seven cell layers thick (single integument in Peperomia two cell layers thick). Megagametophyte tetrasporous, usually 8-nucleate, Fritillaria type (in Peperomia Peperomia type; in Manekia and Zippelia usually Drusa type, tetrasporic with three megaspores at chalazal pole, 16-celled, with eleven cells finally at chalazal pole; in Manekia sometimes 16-nucleate, Penaea type). Synergids little differentiated. Antipodal cells proliferating, polyploid. Parietal tissue two to five cell layers thick. In Zippelia the chalazal nuclei are fused. Endosperm development usually ab initio nuclear (rarely cellular), in Peperomia ab initio cellular (cells up to 15-ploid). Endosperm haustorium absent. Embryogenesis piperad.

Fruit A berry or drupe (in Piper often with persistent and sometimes accrescent style), often more or less connate.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat tegmic. Exotesta unspecialized. Mesotesta and endotesta unspecialized. Exotegmen and endotegmen with strongly thickened cell walls (at least transiently developed exotegmic and endotegmic layers; in Zippelia and some species of Piper only tanniniferous endotegmen). Perisperm copious, with starch grains, surrounding endosperm and embryo; some walls of perisperm cells degrading and their cell nuclei fusing and oil-storing. Endosperm scarce, enclosing embryo at micropylar end. Embryo small, straight, little differentiated, chlorophyll? Suspensor at least sometimes absent. Cotyledons two, small, rudimentary. Germination phanerocotylar. Radicula persistent?

Cytology x = 11 (Peperomia); x = 13 (Piper); x = 19 (Zippelia) – Polyploidy occurring, especially in Peperomia.

DNA Nuclear gene PHYE lost. Mitochondrial coxI intron present in Peperomia.

Phytochemistry Flavones, flavanones, mono- and sesquiterpenes, steroids, propenylphenols (eugenol, safrole, myristicine, etc.), alkaloids (aporphine derivatives rare, isoquinoline alkaloids?), lignans, neolignans, kavapyrones (α-pyrones), chalcones and dihydrochalcones, and cinnamoylamides (piperolides etc.) present. Flavonols, ellagic acid, tannins, and proanthocyanidins not found.

Use Ornamental plants (above all Peperomia), spices (fruits and seeds of Piper nigrum and P. longum, leaves of P. betle for rapping betle nuts), stimulantia (Piper methysticum), medicinal plants.

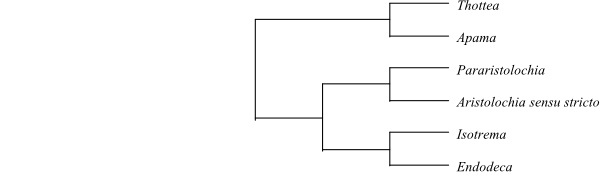

Systematics 5/c 3.600. Verhuellia (2; V. elegans, V. hydrocotylifolia; Cuba, Hispaniola); Zippelia (1; Z. begoniifolia; Southeast Asia, Java), Manekia (6; M. incurva, M. naranjoana, M. obtusa, M. sydowii, M. urbanii, M. venezuelana; Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America); Piper (>1.000; tropical and subtropical regions), Peperomia (1.500–1.600; tropical and subtropical regions).

Piperaceae are sister-group to Saururaceae.

The herbaceous Verhuellia is sister to the remaining Piperaceae. The inflorescence is a spike with each flower subtended by a bract. The stamens are usually two (sometimes three). The anthers are basifixed, tetrasporangiate, latrorse, and longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). The pollen grains are minute, inaperturate, and areolate, with a microechinate exine. The pistil is composed of three or four carpels and the ovary is unilocular. The style is absent and the stigma is trilobate or quadrilobate. The placentation is basal and there is a single orthotropous and unitegmic ovule per ovary. The fruit is a drupe with multicellular epidermal processes.

Zippelia (Southeast Asia) is a small shrub, sister to Manekia. The flower has six stamens with tetrasporangiate anthers. The pollen grains are monosulcate. The pistil is composed of three or four carpels and the ovary is unilocular. There is a single bitegmic ovule per ovary. Manekia (Central and South America) consists of lignified lianas. The flower has four stamens with tetrasporangiate anthers. The pollen grains are monosulcate. The pistil is composed of four or five carpels and the ovary is unilocular. There is one bitegmic ovule in each ovary. The megagametophyte is 16-celled. Zippelia and Gymnotheca (Saururaceae) are anatomically intermediate between Piperaceae and Saururaceae.

Peperomia is sister to Piper. CAM physiology is abundant among epiphytic species of Peperomia. The stem vascular tissue in Peperomia forms an atactostele, i.e. with scattered vascular bundles. The leaves are alternate (spiral or distichous) or opposite. Stipules are absent. The leaf base is usually narrow and cuneate. The two stamens have monothecal, disporangiate anthers. The pollen grains are inaperturate. The pistil is composed of a single carpel with penicillate stigma. The single ovule is unitegmic and tenuinucellate, with the integument consisting of two cell layers. The megagametophyte is three-celled with 14 polar nuclei and up to ten-celled with seven polar nuclei, with a high degree of variation. The endosperm development is cellular. The chalazal nuclei are fused. The seeds are endotestal. Often the endosperm has a high degree of polyploidy, with x = up to 15. x = 11.

Piper is subdivided into one American (New World) clade and one Old World clade. The Old World clade consists of one Asiatic clade (including the two endemic African species and a single Australian species), and one Pacific clade. The megagametophyte is eight-celled. Investigated species of Piper contain a huge amount of alkaloids, amides (e.g. piperamides), lignans, neolignans and terpenes.

|

Cladogram of Piperaceae based on DNA sequence data (Wanke & al. 2007; Samain & al. 2010). |

SAURURACEAE F. Voigt |

( Back to Piperales ) |

Saururales E. Mey. in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp. Regn. Veg.: 13. Sep-Oct 1835 [‘Saurureae’]

Genera/species 4/6

Distribution Eastern Himalaya to Japan, Indochina, West Malesia, the Philippines, the eastern, southern and western parts of the United States, northern Mexico.

Fossils Seeds and fruits of Saururus biloba from the Eocene to the Miocene have been described from Europe and Asia. Saururus tuckerae comprises inflorescences and infructescences from the mid-Eocene of British Columbia (Canada).

Habit Bisexual, perennial herbs with articulated stems. Rhizomes and stolons present. Often hygrophytes. Aromatic and with sharp (peppery) taste.

Vegetative anatomy Root epidermis formed from inner layer of root cap. Phellogen cortical (beneath hypodermis). Primary vascular tissue usually consisting of a cylinder of bundles (sometimes several cylinders; in Saururus two cylinders). Endodermis present in stem or absent. Secondary lateral growth usually absent (Anemopsis with cambium). Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates (in Gymnotheca also spiral-shaped; Anemopsis also with vessel elements with simple perforation plates); lateral pits usually opposite or scalariform (occasionally alternate). Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids or fibre-tracheids with bordered pits. Tyloses sometimes abundant in vessels. Wood rays when present multiseriate (wide and tall), heterocellular. Axial parenchyma paratracheal. Sieve tube plastids S type, with approx. ten starch grains. Nodes ≥5:≥5, pentalacunar or multilacunar with five or more leaf traces. Idioblasts with ethereal oils abundant (absent in Gymnotheca). Calciumoxalate present as druses or rhomboidal crystals.

Trichomes Hairs absent?

Leaves Alternate (ab initio distichous), simple, entire, with involute ptyxis (Anemopsis, Saururus). Stipules simple, intrapetiolar (in Houttuynia more or less perfoliate, in remaining species small) or in reality two connate stipules?, adnate to petiole; leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate or annular. Venation pinnate or palmate. Stomata tetracytic, often surrounded by a whorl of subsidiary cells. Cuticular wax crystalloids as parallel platelets (Convallaria type). Mesophyll with idioblasts containing ethereal oils. Calciumoxalate crystals present. Mesophyll cells with druses. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal, raceme or spike. Basal inflorescence bracts usually petaloid (not in Saururus). Floral prophyll (bracteole) single, median, adaxial.

Flowers Zygomorphic, small. In Saururus hypogyny; in remaining species ab initio hypogyny, later half epigyny in Houttuyia and epigyny in Anemopsis (with bract adnate to a carpel) and Gymnotheca. Tepals absent. Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens usually 3+3 (rarely three [Houttuynia], four or 4+4), whorled. Filaments thin, free, often partially or entirely adnate to ovary. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse to latrorse or extrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually monosulcate (anasulcate; rarely trichotomosulcate), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum, microperforate to punctuate and usually papillate (papillae absent in Gymnotheca), usually psilate (in Gymnotheca microstriate).

Gynoecium Carpels in Anemopsis and Houttuynia usually three, in Gymnotheca and Saururus usually four (rarely three or five), usually largely paracarp and connate (in Saururus connate at base only; ovaries in Anemopsis sunken in inflorescence); carpel usually plicate (in Saururus conduplicate), postgenitally entirely fused, without canal; internal compitum present. Ovary superior to inferior or semi-inferior, usually unilocular (in Saururus multilocular). Stylodia usually three (rarely four or five), free, not completely closed. Stigma decurrent, papillate, Dry type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation usually parietal (in Saururus laminal-lateral). Ovules usually six to ten per carpel (in Saururus usually two to four, rarely one; rarely eleven or twelve), orthotropous to hemianatropous, bitegmic, usually crassinucellar (in Houttuynia incompletely tenuinucellar, with meiocyte hypodermal at apex of megasporangium). Micropyle usually bistomal, Z-shaped (zig-zag; sometimes exostomal). Outer integument two or three cell layers thick. Inner integument two to four cell layers thick. Parietal tissue usually one or two cell layers thick (parietal tissue absent in Houttuynia) Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development usually cellular (sometimes helobial). Endosperm haustorium chalazal. Embryogenesis asterad.

Fruit Usually a dry or fleshy capsule, more or less dehiscent (schizocarp in Saururus consisting of four nut-like mericarps connate at base, indehiscent at maturation) with one seed per carpel.

Seeds Aril? Seed coat testal-tegmic. Exotesta with strongly thickened cell walls (sometimes lignified). Endotesta unspecialized. Exotegmen and endotegmen with strongly thickened cell walls. Perisperm copious, with starch as conglomerated grains. Endosperm scarce, surrounding embryo at micropylar end. Embryo very small, little differentiated (lacking organs). Suspensor present in Houttuynia. Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar. Radicula persistent.

Cytology x = 9 (Gymnotheca); x = 11, 12 (Anemopsis, Saururus); n = 96 (x = 12, Houttuynia, possibly apomictic) – Polyploidy occurring in Anemopsis.

DNA The nuclear gene PHYE is absent?

Phytochemistry Insufficiently known. Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), cyanidin, proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins?), lignans (manassantins, saucernetin, sauchinone, etc.), sesquineolignans (saucerneols), and different ethereal oils (similar to those in Piperaceae) present. Ellagic acid and alkaloids not found.

Use Ornamental plants, medicinal plants, vegetables.

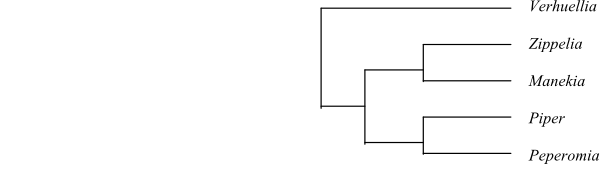

Systematics Anemopsis (1; A. californica; southwestern United States, northwestern Mexico), Gymnotheca (2; G. chinensis; southwestern China, northern Vietnam; G. involucrata: southern Sichuan); Houttuynia (1; H. cordata; Nepal, southern China, the Korean Peninsula, Japan, Southeast Asia, the Philippines, Java), Saururus (2; S. chinensis: China, Japan; S. cernuus: Florida and eastern Texas to Michigan and Ontario).

Saururaceae are sister-group of Piperaceae.

[Houttuynia+Anemopsis] is sister-group to [Saururus+Gymnotheca], according to several DNA analyses. Zippelia (Piperaceae) and Gymnotheca (Saururaceae) are anatomically intermediate between Piperaceae and Saururaceae, most probably due to parallelisms.

|

Cladogram of Saururaceae based on DNA sequence data (Meng & al. 2002, 2003; Neinhuis & al. 2005). |

Literature

Adams CA, Baskin JM, Baskin CC. 2005. Comparative morphology of seeds of four closely related species of Aristolochia subgenus Siphisia (Aristolochiaceae, Piperales). – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 148: 433-436.

Arias T, Williams JH. 2008. Embryology of Manekia naranjoana (Piperaceae) and the origin of tetrasporic, 16-nucleate female gametophytes in Piperales. – Amer. J. Bot. 95: 272-285.

Arias T, Callejas R, Bornstein A. 2006. New combinations in Manekia, an earlier name for Sarcorhachis (Piperaceae). – Novon 16: 205-208.

Asmarayani R. 2018. Phylogenetic relationships in Malesian-Pacific Piper (Piperaceae) and their implications for systematics. – Taxon 67: 693-724.

Baillon HE. 1886. Hydnoraceae trib. Aristolochiacearum. – Librairie Hachette, Paris.

Balfour E. 1957. The development of the vascular systems in Macropiper excelsum Forst. I. The embryo and seedling. – Phytomorphology 7: 354-364.

Balfour E. 1958. The development of the vascular systems in Macropiper excelsum Forst. II. The nature stem. – Phytomorphology 8: 224-233.

Beccari O. 1871. Descrizione die due nuove specie d’Hydnora l’Abissinia. – Nuovo Giorn. Bot. Italiano 3: 6-7.

Beentje H, Luke Q. 2002. Hydnoraceae. – In: Beentje HJ, Ghazanfar SA (eds), Flora of tropical East Africa, A. A. Balkema, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, pp. 1-7.

Behnke H-D. 1971. Zum Feinbau der Siebröhrenplastiden von Aristolochia und Asarum (Aristolochiaceae). – Planta 97: 62-69.

Behnke H-D. 1988. Sieve-element plastids, phloem protein, and evolution of flowering plants III. Magnoliidae. – Taxon 37: 699-732.

Behnke H-D. 2003. Sieve-element plastids and evolution of monocotyledons with emphasis on Melanthiaceae sensu lato and Aristolochiaceae-Asaroideae, a putative dicotyledon sister group. – Bot. Rev. 68: 524-544.

Bello MA, Vaslois-Cuesta H, González F. 2006. Aristolochia grandiflora Sw. (Aristolochiaceae): desarrollo y morfología de la flor más larga del mundo. – Rev. Acad. Colombiano Cienc. 30: 181-194.

Berjano R, Roa F, Talavera S, Guerra M. 2009. Cytotaxonomy of diploid and polyploidy Aristolochia (Aristolochiaceae) species based on the distribution of CMA/DAPI bands and 5S and 45S rDNA sites. – Plant Syst. Evol. 280: 219-227.

Blanco MA. 2002. Aristolochia gorgona (Aristolochiaceae), a new species with giant flowers from Costa Rica and Panama. – Brittonia 54: 30-39.

Bornstein AJ. 1989. Taxonomic studies in the Piperaceae I. The pedicellate pipers of Mexico and Central America (Piper subg. Arctottonia). – J. Arnold Arbor. 70: 1-55.

Bornstein AJ. 1996. Proposal to conserve the name Sarcorhachis against Manekia (Piperaceae). – Taxon 45: 323-324.

Bouman F. 1971. Integumentary studies in Polycarpicae I. Lactoridaceae. – Acta Bot. Neerl. 20: 565-569.

Brantjes NBM. 1980. Flower morphology of Aristolochia species and the consequences of pollination. – Acta Bot. Neerl. 29: 212-213.

Brauner S, Crawford DJ, Stuessy TF. 1992. Ribosomal DNA and RAPD variation in the rare plant family Lactoridaceae. – Amer. J. Bot. 79: 1436-1439.

Burger WC. 1971. Flora Costaricensis. Piperaceae. – Fieldiana, Bot. 35: 5-227.

Burger WC. 1972. Evolutionary trends in the Central American species of Piper (Piperaceae). – Brittonia 24: 356-362.

Burger WC. 1977. The Piperales and the monocots. Alternative hypotheses for the origin of monocotyledonous flowers. – Bot. Rev. 43: 345-393.

Cai Z, Penaflor C, Kuehl JV, Leebens-Mack J, Carlson JE, dePamphilis CW, Boore JL, Jansen RK. 2006. Complete chloroplast genome sequences of Drimys, Liriodendron, and Piper: implication for the phylogeny of magnoliids. – BMC Evol. Biol. 6: 77.

Callejas R. 1986. Taxonomic revision of Piper subgenus Ottonia (Piperaceae). – Ph.D. diss., City University, New York.

Campbell DH. 1900. A peculiar embryo sac in Peperomia pellucida. – Ann. Bot. 13: 626.

Campbell DH. 1901. The embryo sac of Peperomia. – Ann. Bot. 15: 103-118.

Carlquist SJ. 1964. Morphology and relationships of the Lactoridaceae. – Aliso 5: 421-435.

Carlquist SJ. 1990. Wood anatomy and relationships of Lactoridaceae. – Amer. J. Bot. 77: 1498-1505.

Carlquist SJ. 1993. Wood and bark anatomy of Aristolochiaceae: systematic and habital correlations. – IAWA J. 14: 341-357.

Carlquist SJ, Dauer K, Nishimura SY. 1995. Wood and stem anatomy of Saururaceae with reference to ecology, phylogeny, and origin of the monocotyledons. – IAWA J. 16: 133-150.

Chaveerach A, Tanee T, Sanubol A, Monkheang P, Sudmoon R. 2016. Efficient DNA barcode regions for classifying Piper species (Piperaceae). – PhytoKeys 70: 1-10.

Cheng CY, Yang CS. 1983. A synopsis of the Chinese species of Asarum (Aristolochiaceae). – J. Arnold Arbor. 64: 565-597.

Chodat R. 1915. Les espèces du genre Prosopanche. – Bull. Soc. Bot. Genève 7: 65-66.

Cocucci AE. 1965. Estudios en el género Prosopanche (Hydnoraceae) I. Revisión taxonómica. – Kurtziana 2: 53-74.

Cocucci AE. 1975. Estudios en el género Prosopanche (Hydnoraceae) II. – Kurtziana 8: 7-15.

Cocucci AE. 1976. Estudios en el género Prosopanche (Hydnoraceae) III. Embriología. – Kurtziana 9: 19-39.

Cocucci AE, Cocucci AA. 1996. Prosopanche (Hydnoraceae): somatic and reproductive structures, biology, systematics, phylogeny and potentialities as a parasitic weed. – In: Moreno MT, Cubero JI, Berner D, Joel D, Musselman LJ, Parker C (eds), Advances in parasitic plant research, Junta de Andalucia, Dirección General de Investigación Agraria, Cordoba, Spain.

Coe FG, Bornstein AJ. 2009. A new species of Piper (Piperaceae) from Cordillera Nombre de Dios, Honduras. – Syst. Bot. 34: 492-495.

Coiffard C, Mohr BAR, Bernardes-de-Oliveira

MEC. 2015. Hexagyne philippiana gen. et sp. nov., a piperalean

angiosperm from the Early Cretaceous of northern Gondwana (Crato Formation,

Brazil). – Taxon 63: 1275-1286.

Correns C. 1891. Beiträge zur biologischen Anatomie der Aristolochia-Blüte. – Jahrb. Wiss. Bot. 22: 161-189.

Cotinguiba F, Regasini LO, Bolzani V da Silva, Debonsi HM, Passerini GD, Cicarelli RMB, Kato MJ, Furlan M. 2009. Piperamides and their derivatives as potential anti-trypanosomal agents. – Med. Chem. Res. 18: 703-711.

Crawford DJ, Stuessy TF, Silva OM. 1986. Leaf flavonoid chemistry and the relationships of the Lactoridaceae. – Plant Syst. Evol. 153: 133-139.

Dahlstedt H. 1900. Studien über Süd- und Central-amerikanische Peperomia. – Kungl. Sv. Vetensk.-Akad. Handl. 33(2): 1-218.

Dan M, Mathew PJ, Unnithan CM, Pushpangadan P. 1996. Thottea abrahamii a new species of Aristolochiaceae from Peninsular India. – Kew Bull. 51: 179-182.

Dasgupta A, Datta PC. 1976. Cytotaxonomy of Piperaceae. – Cytologia 41: 697-706.

Dastur NH. 1922. Notes on the development of the ovule, embryo sac, and embryo of Hydnora africana. – Trans. Roy. Soc. South Afr. 10: 27-31.

Datta PC, Dasgupta A. 1977. Comparison of vegetative anatomy of Piperales 1-2. – Acta Biol. Acad. Sci. Hungar. 28: 81-96, 97-110.

Daumann E. 1959. Zur Kenntnis der Blütennektarien von Aristolochia. – Preslia 31: 359-372.

Daumann E. 1971. Contribution to the pollination ecology of the species Aristolochia clematitis L. – Preslia 43: 105-111.

Davis PH, Khan MS. 1961. Aristolochia in the Near East. – Notes Roy. Bot. Gard. Edinb. 23: 515-546.

De Bary A. 1868. Prosopanche burmeisteri, eine neue Hydnoree aus Süd-Amerika. – Abh. Naturf. Ges. Halle 10: 243-272.

Decaisne MJ. 1873. Note sur trois espèces d’Hydnora. – Bull. Soc. Bot. Franç. 20: 75-77.

De Groot H, Wanke S, Neinhuis C. 2006. Revision of the genus Aristolochia (Aristolochiaceae) in Africa, Madagascar and adjacent islands. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 151: 219-238.

Delaigue M. 1971. Étude morphologique et ontogénique du complexe axillaire d’Aristolochia clematitis L. – Bull. Soc. Bot. France, Mém. 1971: 67-177.

Diaz PP, Arias T, Joseph-nathan P P. 1987. A chromene, an isoprenylated methyl hydroxybenzoate and a C-methyl flavanone from the bark of Piper hostmannianum. – Phytochemistry 26: 809-811.

Dickison WC. 1992. Morphology and anatomy of the flower and pollen of Saruma henryi Oliv., a phylogenetic relict of the Aristolochiaceae. – Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 119: 392-400.

Dickison WC. 1996. Stem and leaf anatomy of Saruma henryi Oliv., including observations on raylessness in the Aristolochiaceae. – Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 123: 261-267.

Ding Hou. 1984. Aristolochiaceae. – In: Steenis CGGJ van (ed), Flora malesiana I, 10(1), Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague, Boston, London, pp. 53-108.

Dormer KJ. 1955. Asarum europaeum – a critical case in vascular morphology. – New Phytol. 54: 338-342.

Doskotch RW, Vanevenhoren PW. 1967. Isolation of aristolochic acid from Asarum canadense. – J. Nat. Prod. 30: 141-143.

Düll R. 1973. Die Peperomia-Arten Afrikas. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 93: 56-129.

Dwuma-Badu D, Ayim JS, Dabra TT. 1975. Constituents of West African medicinal plants IX. Dihydrocubebin, a new lignan from Piper guineense. – Lloydia 38: 343-345.

Dyer LA, Richards J, Dodson CD. 2004. Isolation, synthesis, and evolutionary ecology of Piper amides. –

Engler A. 1887a. Über die Familie der Lactoridaceen. – Engl. Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 8: 53-56.

Engler A. 1887b. Lactoridaceae. – In: Engler A, Prantl K (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien III(2), W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 19-23.

Engler A. 1889a. Saururaceae. – In: Engler A, Prantl K (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien III(1), W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 1-3.

Engler A. 1889b. Piperaceae. – In: Engler A, Prantl K (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien III(1), W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 3-11.

Engler A. 1891. Lactoridaceae. – In: Engler A, Prantl K (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien III(2), W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 19-20.

Erdtman G. 1964. Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Pollenmorphologie von Lactoris fernandeziana und Drimys winteri. – Grana Palynol. 5: 33-39.

Escarré A. 1969. Aportaciones al conocimento de la flora de Fernando Po II: Piperaceae, Urticaceae. – Acta Phytotaxon. Barcinonensia 3(5).

Fleming TH. 2004. Dispersal ecology of neotropical Piper shrub and treelets. – In: Dyer LA, Palmer ADN (eds), Piper: a model genus for studies of phytochemistry, ecology, and evolution, Kluwer Academic, New York, pp. 58-77.

Frenzke L, Scheiris E, Pino G, Symmank L, Goetghebeur P, Neinhuis C, Wanke S, Samain M-S. 2015. A revised infrageneric classification of the genus Peperomia (Piperaceae). – Taxon 64: 424-444.

Gaddy LL. 1987. A review of the taxonomy and biogeography of Hexastylis (Aristolochiaceae). – Castanea 52: 186-196.

Gajurel PR, Rethy P, Kumar Y. 2001. A new species of Piper (Piperaceae) from Arunachal Pradesh, north-eastern India. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 137: 417-419.

Gamerro JC, Barreda V. 2008. New fossil record of Lactoridaceae in southern South America: a palaeobiogeographical approach. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 158: 41-50.

Gilmartin AJ. 1981. Morphological variation within five angiosperm families: Asclepiadaceae, Bromeliaceae, Melastomataceae, Piperaceae, and Rubiaceae. – Syst. Bot. 6: 331-345.

Gomez PLD, Gomez-L J. 1981. A new species of Prosopanche from Costa Rica. – Phytologia 49: 53-55.

González F. 1991. Notes on the systematics of Aristolochia subsect. Hexandrae. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 78: 497-503.

González F. 1994. 58. Aristolochiaceae. – In: Harling G, Andersson L (eds), Flora of Ecuador 51, Nord. J. Bot., Copenhagen, pp. 1-42.

González F. 1997. Hacia una filogenia de Aristolochia y sus congéneres neotropicales. – Caldesia 19: 93-108.

González F. 1999a. Inflorescence morphology and the systematics of Aristolochiaceae. – Syst. Geogr. Plants 68: 159-172.

González F. 1999b. A phylogenetic analysis of the Aristolochioideae (Aristolochiaceae). – Ph.D. diss., The City University of New York.

González F. 2000. Notes on the Central Andean species of Aristolochia (Aristolochiaceae) with the description of a new species from Bolivia. – Kew Bull. 55: 905-916.

González F, Rudall PJ. 2001. The questionable affinities of Lactoris: evidence from branching pattern, inflorescence morphology, and stipule development. – Amer. J. Bot. 88: 2143-2151.

González F, Rudall PJ. 2003. Structure and development of the ovule and seed in Aristolochiaceae, with particular reference to Saruma. – Plant Syst. Evol. 241: 223-244.

González F, Stevenson DW. 2000a. Perianth development and systematics of Aristolochia. – Flora 195: 370-391.

González F, Stevenson DW. 2000b. Gynostemium development in Aristolochia (Aristolochiaceae). – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 122: 249-291.

González F, Stevenson DW. 2002. A phylogenetic analysis of the subfamily Aristolochioideae (Aristolochiaceae). – Revist. Acad. Colombiana Ci. Exact. Físic. Nat. 26: 25-58.

González F, Rudall PJ, Furness CA. 2001. Microsporogenesis and systematics of Aristolochiaceae. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 137: 221-242.

González F, Ospina JC, Zanotti C. 2015. Sinopsis y novedades taxonómicas de la familia Aristolochiaceae para la Argentina. – Darwiniana 2015: 38-64.

Grayum MH. 1996. Notes on Costa Rican Peperomia, including four new species. – Phytologia 79: 108-113.

Gregory MP. 1956. A phyletic rearrangement in the Aristolochiaceae. – Amer. J. Bot. 43: 110-122.

Guédès M. 1968. La feuille vegetative et le périanthe de quelques Aristoloches. – Flora, Sect. B, 158: 167-179.

Hagerup O. 1961. The perianthium of Aristolochia elegans. – Mast. Bull. Res. Counc. Israel, Sect. D, 10: 348-351.

Harms H. 1935. Hydnoraceae. – In: Engler A (†), Harms H (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien, 2. Aufl., Bd. 16b, W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 282-295.

Hayashi H, Sholichin M, Sakao T, Yamamura Y, Komae H. 1980. An approach to chemotaxonomy of the Asarum subgenus Heterotropa. – Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 8: 109-113.

Hegnauer R. 1960. Chemotaxonomische Betrachtungen II. Phytochemische Hinweise für die Stellung der Aristolochiaceae im System der Dicotyledonen. – Die Pharmazie 15: 634-642.

Hoehne FC. 1927. Monographia ilustrada das Aristolochiaceas brasileiras. – Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 20: 67-175.

Hoffstadt RE. 1916. The vascular anatomy of Piper methysticum. – Bot. Gaz. 62: 115-132.

Hofmann C-C, Zetter R. 2010. Upper Cretaceous sulcate pollen from the Timerdyakh formation, Vilui Basin (Siberia). – Grana 49: 170-193.

Horner HT, Wanke S, Samain M-S. 2009. Evolution and systematic value of leaf crystal macropatterns in the genus Peperomia (Piperaceae). – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 170: 343-354.

Horner HT, Wanke S, Samain M-S. 2012. A comparison of leaf crystal macropatterns in the two sister genera Piper and Peperomia (Piperaceae). – Amer. J. Bot. 99: 983-997.

Howard RA. 1973. Notes on the Piperaceae of the Lesser Antilles. – J. Arnold Arbor. 54: 382-397.

Huber H. 1985. Samenmerkmale und Gliederung der Aristolochiaceen. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 107: 277-320.

Huber H. 1993. Aristolochiaceae. – In: Kubitzki K, Rohwer JG, Bittrich V (eds), The families and genera of vascular plants II. Flowering plants. Dicotyledons. Magnoliid, hamamelid and caryophyllid families, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 129-137.

Hwang BY, Lee J-H, Nam JB, Hong Y-S, Lee JJ. 2003. Lignans from Saururus chinensis inhibiting the transcription factor NF-kB. – Phytochemistry 64: 765-771.

Ionescu F, Jolad SD, Cole JR. 1977. Dehydrodiisoeugenol: a naturally occurring lignan from Aristolochia taliscana (Aristolochiaceae). – J. Pharm. Sci. 66: 1489-1490.

Isnard S, Prosperi J, Wanke S, Wagner ST, Samain M-S, Trueba S, Frenzke L, Neinhuis C, Rowe NP. 2012. Growth form evolution in Piperales and its relevance for understanding angiosperm diversification: an integrative approach combining plant architecture, anatomy, and biomechanics. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 173: 610-639.

Jaramillo MA, Callejas R. 2004. Current perspectives on the classification and phylogenetics of the genus Piper L. – In: Dyer LA, Palmer ADN (eds), Piper: A model genus for studies of phytochemistry, ecology, and evolution, Kluwer Academic, New York, pp. 179-198.

Jaramillo MA, Kramer EM. 2004. APETALA3 and PISTILLATA homologs exhibit novel expression patterns in the unique perianth of Aristolochia (Aristolochiaceae). – Evol. Developm. 6: 449-458.

Jaramillo MA, Kramer EM. 2007. Molecular evolution of the petal and stamen identity genes, APETALA3 and PISTILLATA, after petal loss in the Piperales. – Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 44: 598-609.

Jaramillo MA, Manos PS. 2001. Phylogeny and patterns of floral diversity in the genus Piper (Piperaceae). – Amer. J. Bot. 88: 706-716.

Jaramillo MA, Manos PS, Zimmer EA. 2004. Phylogenetic relationships of the perianthless Piperales: reconstructing the evolution of floral development. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 165: 403-416.

Jaramillo MA, Callejas R, Davidson C, Smith JF, Stevens AC, Tepe EJ. 2008. A phylogeny of the tropical genus Piper using ITS and the chloroplast intron psbJ-petA. – Syst. Bot. 33: 647-660.

Jebb M. 1993. Aristolochia in New Guinea. – Christensen Research Institute.

Johri BM, Bhatnagar SP. 1955. A contribution to the morphology and life history of Aristolochia. – Phytomorphology 5: 123-136.

Kamelina OP. 1997. Dopolneniya k embriologii semeystv Lactoridaceae i Fouquieriaceae. – Bot. Žurn. 82: 25-29.

Kanta K. 1962. Morphology and embryology of Piper nigrum L. – Phytomorphology 12: 207-221.

Kelly LM. 1997. A cladistic analysis of Asarum (Aristolochiaceae) and implications for the evolution of herkogamy. – Amer. J. Bot. 84: 1752-1765.

Kelly LM. 1998. Phylogenetic relationships in Asarum (Aristolochiaceae) based on morphology and ITS sequences. – Amer. J. Bot. 85: 1454-1467.

Kelly LM. 2001. Taxonomy of Asarum section Asarum (Aristolochiaceae). – Syst. Bot. 26: 17-53.

Kelly LM, González F. 2003. Phylogenetic relationships in Aristolochiaceae. – Syst. Bot. 28: 236-249.

Kondo K, Na H, Gu Z, Fan Q, Xia L. 1987. A karyomorphological study in four species of Asarum from Yunnan, China. – Kromosomo 2: 1495-1501.

Kubitzki K. 1993. Lactoridaceae. – In: Kubitzki K, Rohwer JG, Bittrich V (eds), The families and genera of vascular plants II. Flowering plants. Dicotyledons. Magnoliid, hamamelid and caryophyllid families, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 359-361.

Kulkarni AR, Patil KS. 1977. Aristolochioxylon prakashii from the Deccan Intertrappean beds of Wardha district, Maharashtra. – Geophytology 7: 44-49.

Lammers TG, Stuessy TF, Silva OM. 1986. Systematic relationships of the Lactoridaceae, an endemic family of the Juan Fernández Islands, Chile. – Plant Syst. Evol. 152: 243-266.

Leemann A. 1927. Contribution à l’étude de l’Asarum europaeum L. – Bull. Soc. Bot. Genève 19: 92-173.

Lei L-G, Liang H-X. 1998. Floral development of dioecious species and trends of floral evolution in Piper sensu lato. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 127: 225-237.

Lei L-G, Liang H-X. 1999. Variations in floral development in Peperomia (Piperaceae) and their taxonomic implications. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 131: 423-431.

Lei L-G, Wu Z-Y, Liang H-X. 2002. Embryology of Zippelia begoniaefolia (Piperaceae) and its systematic relationships. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 140: 49-64. – Erratum: 2003. Bot J. Linn. Soc. 141: 255.

Leinfellner W. 1953. Die hypopeltaten Brakteen von Peperomia. – Österr. Bot. Zeitschr. 100: 601-615.

Leins P, Erbar C. 1985. Ein Beitrag zur Blütenentwicklung der Aristolochiaceen, einer Vermittlergruppe zu den Monokotylen. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 107: 343-368.

Leins P, Erbar C. 1995. Das frühe Differenzierungsmuster in den Blüten von Saruma henryi Oliv. (Aristolochiaceae). – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 117: 365-376.

Leins P, Erbar C, Heel WA van. 1988. Note on the floral development of Thottea (Aristolochiaceae). – Blumea 33: 357-370.

Letourneau DK. 1983. Passive aggression an alternative hypothesis for the Piper-Pheidole association. – Oecologia 60: 122-126.

Letourneau DK. 1990. Code of ant-plant mutualism broken by parasite. – Science 248: 215-217.

Liang H-X. 1991. Karyomorphology of Gymnotheca and phylogeny of four genera in Saururaceae. – Acta Bot. Yunnan. 13: 303-307. [In Chinese]

Liang H-X. 1992. Study on the pollen morphology of Saururaceae. – Acta Bot. Yunnan. 14: 401-404. [In Chinese]

Liang H-X, Tucker SC. 1989. Floral development in Gymnotheca chinensis (Saururaceae). – Amer. J. Bot. 76: 806-819.

Liang H-X, Tucker SC. 1990. Comparative studies of the floral vasculature in Saururaceae. – Amer. J. Bot. 77: 607-623.

Liang H-X, Tucker SC. 1995. Floral ontogeny of Zippelia begoniaefolia and its familial affinity: Saururaceae or Piperaceae? – Amer. J. Bot. 82: 681-689.

Machado RF, Queiroz LP de. 2012. A new species of Prosopanche (Hydnoraceae) from northeastern Brazil. – Phytotaxa 75: 58-64.

Macphail MK, Partridge AD, Truswell EM. 1999. Fossil pollen records of the problematical primitive angiosperm family Lactoridaceae in Australia. – Plant Syst. Evol. 214: 199-210.

Madrid EN, Friedman WE. 2008. Female gametophyte development in Aristolochia labiata Willd. (Aristolochiaceae). – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 158: 19-29.

Madrid EN, Friedman WE. 2009. The developmental basis of an evolutionary diversification of female gametophyte structure in Piper and Piperaceae. – Ann. Bot. 103: 869-884.

Madrid EN, Friedman WE. 2010. Female gametophyte and early seed development in Peperomia (Piperaceae). – Amer. J. Bot. 97: 1-14.

Majumdar GP, Pal P. 1961. Developmental studies VI. The morphology of the so-called stipule of Piper, etc. – Proc. Natl. Inst. Sci. India, Sect. B, 27: 26-39.

Malme G. 1904. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der südamerikanischen Aristolochiaceen. – Ark. f. Bot. 1: 521-551.

Marloth R. 1907. Notes on the morphology and biology of Hydnora africana Thunb. – Trans. South Afr. Phil. Soc. 16: 465-468.

Martínez C, Carvalho MR, Madriñán S, Jaramillo CA. 2015. A Late Cretaceous Piper (Piperaceae) from Colombia and diversification patterns for the genus. – Amer. J. Bot. 102: 273-289.

Martínez Colín MA, Engleman EM, Koch SD. 2006. Contribución al conocimiento de Peperomia (Piperaceae): fruto y semilla. – Bol. Soc. Bot. México 78: 83-94.

Mathieu G. 2003a. New endemic Peperomia species (Piperaceae) from Madagascar. – Syst. Geogr. Plants 73: 71-81.

Mathieu G. 2003b. Peperomia nicolliae, a new endemic species (Piperaceae) from Madagascar. – Syst. Geogr. Plants 73: 288-290.

Mathieu G, Callejas Posada R. 2006. New synonymies in the genus Peperomia Ruiz & Pav. (Piperaceae) – an annotated checklist. – Candollea 61: 331-363.