“ERICIDAE”

[Ericales+Gentianidae]

ERICALES Bercht. et J. Presl

Berchtold et Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 251. Jan-Apr

1820 [‘Ericeae’]

Ericopsida Bartl.,

Ord. Nat. Plant.: 120, 152. Sep 1830 [’Ericineae’];

Ericanae Takht., Sist. Filog. Cvetk. Rast. [Syst.

Phylog. Magnolioph.]: 221. 4 Feb 1967; Theanae R.

Dahlgren ex Reveal in Phytologia 74: 179. 25 Mar 1993;

Primulanae R. Dahlgren ex Reveal in Phytologia 79:

71. 29 Apr 1996; Theidae Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant.

Vasc.: xliii. 23 Dec 2001; Ericidae C. Y. Wu in Acta

Phytotaxon. Sin. 40: 308. 2002

Fossils Actinocalyx

bohrii from the Late Santonian to the Early Campanian of Sweden comprises

hypogynous flowers with a pentamerous biserial perianth, five haplostemonous

stamens and three connate carpels. The five petals are basally connate and the

filaments are adnate to the corolla. The pollen grains are tricolpate with a

finely foveolate exine. The ovary is trilocular, the placentation is central,

the ovules are anatropous and the fruits are capsular. Paradinandra

suecica from the Late Santonian to the Early Campanian of Sweden resembles

Actinocalyx, although it has basally connate stamens which are

arranged in an outer whorl of five and an inner whorl of ten stamens. The

paired stamens were probably antepetalous and solitary stamens were possibly

likewise antepetalous. There is an intrastaminal nectariferous disc. The

anthers probably dehisced by apical pores or slits, and the pollen grains were

tricolpate. The placentation is intrusively parietal and the ovules are

campylotropous.

Paleoenkianthus sayrevillensis, from

the Turonian of New Jersey, is represented by hypogynous pentamerous flowers

and fruits. The petals are basally connate and have a valvate aestivation.

There is one series of eight stamens with inverted anthers bearing two or three

appendages at their base, and the pollen grains are probably tricolporate with

reticulate exine. The four connate carpels form a quadrilocular ovary with four

free styles, and developed into a capsule with septicidal-loculicidal

dehiscence.

Pentapetalum trifasciculandricum, from

the Turonian of New Jersey, includes pentamerous hypogynous flowers with a

large number of stamens in three fascicles, and three carpels forming free

styles and a trilocular ovary containing numerous ovules.

‘Pentaphylax’ protogaea, fossil fruits from the

Maastrichtian of Germany, has been assigned to the extant Pentaphylacaceae, although

there are several important differences. The fossils have a thick lignified

pericarp and the persistent calyx lobes have unequal length. Moreover, the

seeds are anatropous.

Habit Bisexual, monoecious,

polygamomonoecious, dioecious, polygamodioecious or functionally monoecious,

dioecious or gynodioecious, evergreen or deciduous trees, shrubs, suffrutices

or lianas, or perennial, biennial or annual herbs.

Vegetative anatomy Usually

with arbuscular mycorrhiza with Glomales. Phellogen ab initio

superficially or deeply seated. Secondary lateral growth normal or absent.

Vessel elements with scalariform or simple (sometimes reticulate) perforation

plates; lateral pits usually alternate, scalariform or opposite, simple or

bordered pits (vessels occasionally absent). Pit membrane remnants may occur in

some species. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids or fibre tracheids

with bordered pits, non-septate (sometimes also vasicentric tracheids). Wood

rays uniseriate or multiseriate, usually heterocellular (sometimes

homocellular), or absent. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or

diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal scanty vasicentric, reticulate,

unilateral or banded (rarely aliform, confluent or scalariform), or absent.

Sieve tube plastids usually Ss type (sometimes Pcf type). Nodes usually 1:1,

unilacunar with one trace (rarely 3:3, trilacunar with three traces).

Idioblasts with mucilage often present. Laticifers with milky latex

occasionally present; ducts with gutta-percha sometimes present. Parenchyma

often with idioblasts containing calciumoxalate raphides. Prismatic or acicular

crystals, crystal sand, styloids or druses sometimes present.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or

multicellular, uniseriate or multiseriate, simple or branched, bristle-like,

flattened, furcate, stellate or dendritic (sometimes fasciculate, T-shaped,

candelabra-, funnel- or cup-shaped, rarely arachnoid, peltate or lepidote), or

absent; multicellular glandular hairs with capitate head (sometimes thick and

colleter-like, rarely peltate-lepidote) sometimes present.

Leaves Usually alternate

(spiral or sometimes distichous, rarely tetrastichous; rarely opposite or

verticillate), simple, entire, sometimes coriaceous or ericoid (rarely

scale-like), with conduplicate, supervolute, involute, convolute or revolute

(rarely circinnate or plicate) ptyxis. Stipules very small and caducous or

absent; leaf sheath absent. Colleters often abundant. Petiole vascular bundle

transection arcuate or annular (sometimes D-shaped or complex, sometimes with

one or two medullary bundles). Venation pinnate, eucamptodromous,

brochidodromous, craspedodromous or semicraspedodromous (rarely

reticulodromous, acrodromous to palinactinodromous or actinodromous), or leaves

single-veined; vascular bundles often collateral; some veins proceeding into

teeth. Stomata usually anomocytic (sometimes paracytic, anisocytic, cyclocytic

or actinocytic, rarely stephanocytic, staurocytic or parallelocytic). Cuticular

wax crystalloids as platelets or rodlets (sometimes amorphous or as tubuli

dominated by diketones), or absent. Epidermis with or without mucilage cells.

Mesophyll often with calciumoxalate raphides. Mesophyll with or without

sclerenchymatous idioblasts containing brachysclereids, osteosclereids and

other kinds of sclereids. Secretory oil cavities present or absent. Ducts with

gutta-percha sometimes present. Leaf margin usually serrate or entire

(sometimes crenate). Leaf tooth apex often widened, translucent, persistent,

sometimes gland-tipped (rarely with nectariferous glands); teeth often theoid,

with single vein and opaque deciduous cap (sometimes with single multicellular

hair replacing cap).

Inflorescence Usually axillary

(sometimes terminal), panicle, thyrsopaniculate, thyrsoid, botryoid,

fasciculate, corymbose, head-, umbel-, raceme- or spike-like, cymose or

racemose (flowers sometimes solitary, axillary or terminal). Floral prophylls

(bracteoles) present or absent.

Flowers Actinomorphic or

zygomorphic. Usually hypogyny (sometimes epigyny or half epigyny). Sepals (two

to) five (to twelve), with imbricate or valvate (sometimes open, rarely

contorted) aestivation, usually persistent, free or more or less connate.

Petals (three to) five (to 18), with imbricate, valvate or contorted (rarely

conduplicate or subinduplicate) aestivation, usually caducous, free or more or

less connate into hypocrateromorphous, discoid, campanulate, infundibuliform,

tubular or urceolate corolla (sometimes nectariferous at base). Nectary and

disc usually absent (nectariferous disc sometimes annular or consisting of

separate parts, intrastaminal or occasionally extrastaminal, or petals

sometimes nectariferous).

Androecium Stamens (two to)

five to more than 1.200, in one or more whorls (sometimes in fascicles).

Filaments usually free (rarely connate at base), usually free from tepals

(sometimes epipetalous). Anthers dorsifixed, ventrifixed or subbasifixed,

versatile or non-versatile, often inverting and finally resupinate, usually

tetrasporangiate (rarely disporangiate), extrorse or introrse (rarely

latrorse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal or transverse slits) or

poricidal (dehiscing by seemingly apical to subapical pores). Tapetum usually

secretory (rarely amoeboid-periplasmodial). Staminodia sometimes present.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains (2–)3(–6)-colpor(oid)ate,

(2–)3(–5)-colpate or 3(–5)-porate (rarely pantocolporate, pantoporate or

stephanocolpate), usually shed as monads (sometimes tetrads, rarely dyads,

triads or polyads), usually bicellular (rarely tricellular) at dispersal. Exine

tectate or semitectate (rarely intectate), usually with granular (sometimes

columellate) infratectum, pertectate, reticulate, foveolate, scabrate,

fossulate, areolate, rugulate, psilate, gemmate, verrucate, verruculate,

echinate, scrobiculate, granulate or microgranulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

(one to) five to c. 20 (to c. 30) more or less connate carpels. Ovary usually

superior (sometimes inferior or semi-inferior), (unilocular to) quinquelocular

to c. 20(–30)-locular (sometimes incompletely septate). Style single, simple,

or stylodia (three to) five to c. 20, short, free or partially connate,

sometimes persistent. Stigma capitate, punctate, peltate or lobate, papillate

or non-papillate, Dry or Wet type. Male flowers sometimes with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation usually

axile (sometimes apical or parietal, rarely basal; placentae often diffuse).

Ovules one to numerous per carpel, usually anatropous (sometimes hemianatropous

or campylotropous, rarely orthotropous), pendulous to ascending, apotropous or

epitropous, usually unitegmic (sometimes bitegmic), tenuinucellar. Micropyle

endostomal or bistomal (when bitegmic usually endostomal). Megagametophyte

usually monosporous, Polygonum type (sometimes disporous,

Allium type, rarely tetrasporous, Adoxa type). Synergids

sometimes with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells sometimes persistent and

proliferating. Endosperm development usually cellular (sometimes nuclear).

Endosperm haustoria chalazal and/or micropylar or absent. Embryogenesis

solanad, onagrad or asterad (sometimes caryophyllad or chenopodiad).

Fruit A loculicidal and/or

septifragal capsule (rarely a pyxidium or a denticidal capsule), a berry, a

drupe or a samara (rarely a nut enclosed by perianth or a drupaceous

schizocarp), often with persistent and sometimes accrescent calyx.

Seeds Aril usually absent.

Exotesta with inner cell walls of outer epidermis often thickened, with theoid

exotestal thickenings. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious to sparse

(rarely ruminate), oily or proteinaceous. Embryo large to small, usually

straight (sometimes curved), well differentiated, usually without chlorophyll.

Cotyledons two. Germination usually phanerocotylar (rarely cryptocotylar).

Cytology x =

(3–)7–13(–20)

DNA Nuclear gene PI

duplicated. I copy of nuclear gene RPB2 present.

Mitochondrial intron coxII.i3 often lost.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin, gossypetin), catechins, cyanidin,

davidigenin, Route I secoiridoids, Group I carbocyclic iridoids (aucubin,

daphylloside, monotropein), Group II decarboxylated iridoids (e.g. cornine),

Group IV carbocyclic iridoids (rarely unedoside, a C8 iridoid glycoside), Group

VI secoiridoids (morroniside), Group X secoiridoids (nepetalactones,

iridoidpyridine alkaloids), sarracenin, oleanolic acid derivatives,

monoterpenes, diterpenes (e.g. andromedotoxin), sesquiterpenes, triterpenes,

free triterpenic acids (betulinic acid, ursolic acid), dammaranes, arjunolic

acid derivatives, ellagic acid (frequent to absent), gallic acid, ellagitannins

(geraniin, pedunculagin, tellimagrandin II), non-hydrolyzable tannins,

proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins), caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, phenolic

heterosides, 3-galactoside, triterpene saponins, benzoquinones (e.g. arbutin,

rapanone) and naphthoquinones and their derivatives (e.g. naphthoquinone

derivatives of 7-methyljugone, lawsone, plumbagin, droserone), anthraquinones,

polyacetate-derived arthroquinones, benzopyrones, cucurbitacins,

dihydrosterculic acid, lignans (pinoresinol), myo-inositol, and

ethereal oils present. Alkaloids (e.g. pyrrolizidine alkaloids, indole

alkaloids and their glycosides) and cyanogenic compounds rare. Carbohydrates

sometimes stored as oligosaccharides with kestose or isokestose bonds (inulin).

Aluminium accumulated in some groups.

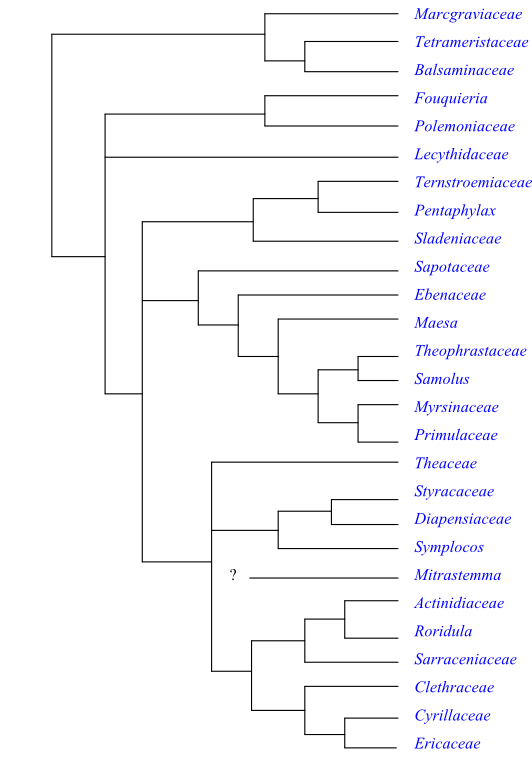

Systematics Ericales are sister-group to

Asteridae except Loasales.

The clade [Balsaminaceae+[Marcgraviaceae+Tetrameristaceae]] is

sister-group to all other Ericales. Potential synapomorphies

are, according to Stevens (2001 onwards): vessel elements with usually simple

perforation plates; vessels in radial multiples; presence of raphid sacs in

stem; presence of branched sclereids; absence of druses; leaf with supervolute

ptyxis; lamina elongating in bud and with obscure abaxial lines; leaf margin

serrate; inflorescence racemose; abaxial petal surface with stomata; filiform

appendages present along stomium; stamens as many as sepals, antesepalous, free

from petals; anthers subbasifixed; ovary with mucilaginous secretions; absence

of gynoecial nectary; style short, stigma little expanded; ovules bitegmic;

micropyle endostomal; presence of micropylar endosperm haustorium; presence of

myricetin; and absence of ellagic acid. Balsaminaceae and Tetrameristaceae share the

synapomorphies: sepals petaloid, nectariferous; filaments postgenitally

connate; and stylar canal present, quinqueradiate.

The leaves in this basal clade are often

glabrous, simple and usually lack stipules (some Balsaminaceae have stipules).

Extrafloral nectaries or glands are often present on the adaxial side of leaf

(including petiole), calyx or corolla. The pollen grains are tricolporate and

bicellular at dispersal, and the ovules are bitegmic and tenuinucellar. The

endosperm development is cellular, endosperm haustorium is present, and the

endosperm is sparse. The nodes are unilacunar in Balsaminaceae and Marcgraviaceae, and there is a

caducous calyptra, developed from androecium (Balsaminaceae) or petals (Marcgraviaceae). Marcgraviaceae and Tetrameristaceae have

indehiscent fruit, and Pelliciera and Marcgraviaceae have large

cortical air cavities.

The Ericales main clade may be

characterized by connate corolla with well developed tube, and long style. The

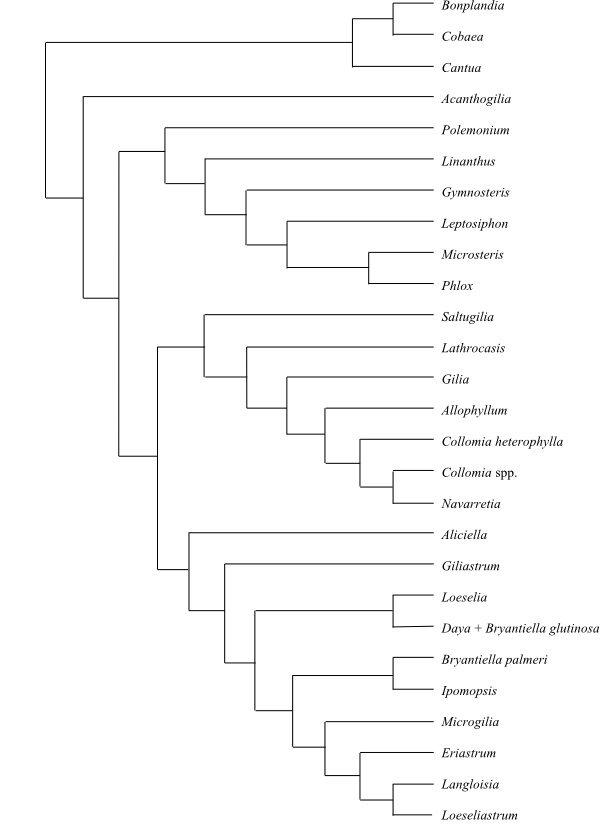

clade [Polemoniaceae+Fouquieriaceae] is part of a

trichotomy forming the base of the remaining Ericales. Fouquieria and

Polemoniaceae share the

potential synapomorphies (Stevens 2001 onwards): phellogen outer-cortical;

vessel elements with simple perforation plates; inflorescence terminal, cymose;

hypogyny; sepals free, with membranous margins and abaxial stomata; petals

largely connate; presence of nectaries; filaments adnate to corolla; anther

thecae largely separate, without septum; pistil composed of three connate

carpels; presence of gynoecial nectary; style hollow, strongly lobate; ovules

arranged in two ranks, apotropous; fruit a loculicidal capsule, with persistent

calyx and seeds inserted on central columella; seed coat winged; endosperm

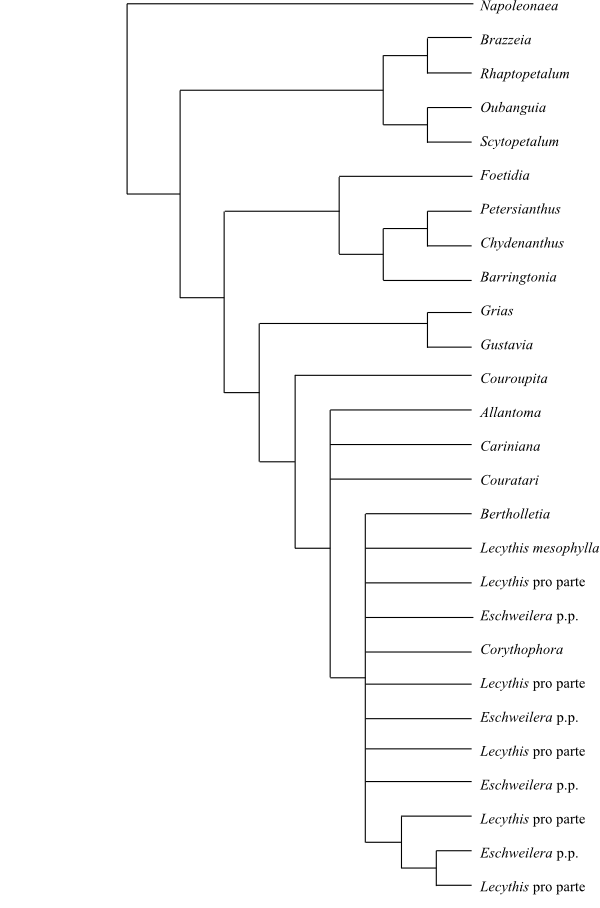

sparse; and loss of mitochondrial intron coxII.i3. Lecythidaceae are the second

lineage of the trichotomy, whereas the third monophyletic group comprises the

main clade of Ericales.

The first of three clades in a basal trichotomy

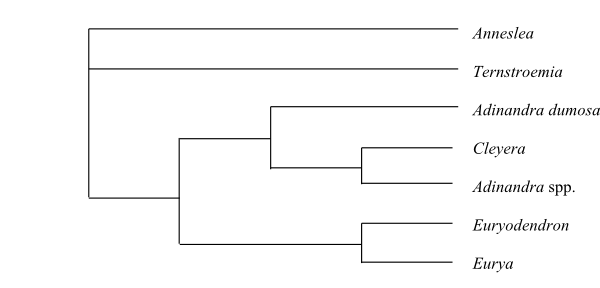

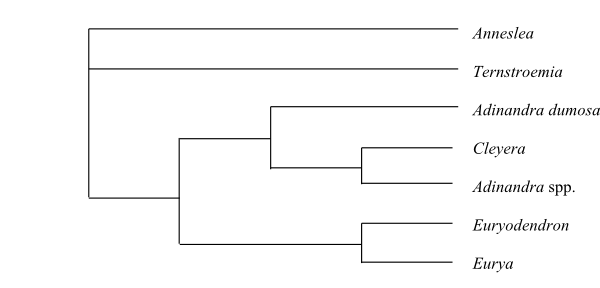

forming the remainder of Ericales has the topology [Sladeniaceae+[Pentaphylacaceae+Ternstroemiaceae]]. This clade

has the following potential synapomorphies (Stevens 2001 onwards): vessel

elements with scalariform perforation plates; bordered vessel-fibre pits; nodes

1:1; presence of mucilage cells; unicellular hairs; petiole vascular bundle

transection arcuate; campanulate corolla; petals less than one centimetre long

and connate only at base; absence of nectary; basifixed anthers; pollen grains

14–30 μm long; exine usually only little ornamented; placentae becoming

swollen; bitegmic ovules; endostomal micropyle; inner integument three or four

cell layers thick; fruit a capsule with columella and calyx persistent;

presence of endosperm; and long embryo. Pentaphylax and Ternstroemiaceae share the

following synapomorphies: parenchyma apotracheal; intervessel pitting

opposite-scalariform; leaves with supervolute ptyxis; flowers solitary axillary

or inflorescence fasciculate; corolla usually greenish to yellowish; style

hollow; ovules campylotropous to hemitropous; mesotesta well developed; embryo

U-shaped; and accumulation of aluminium.

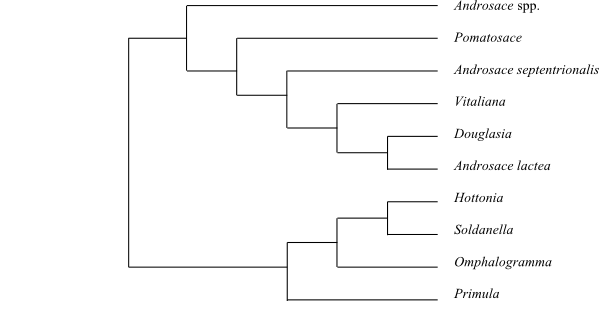

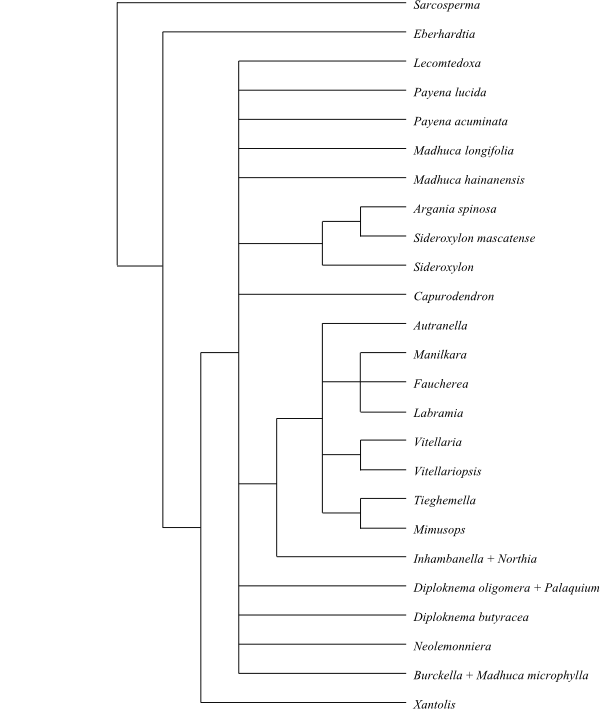

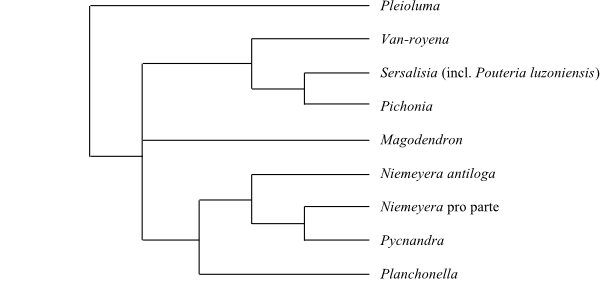

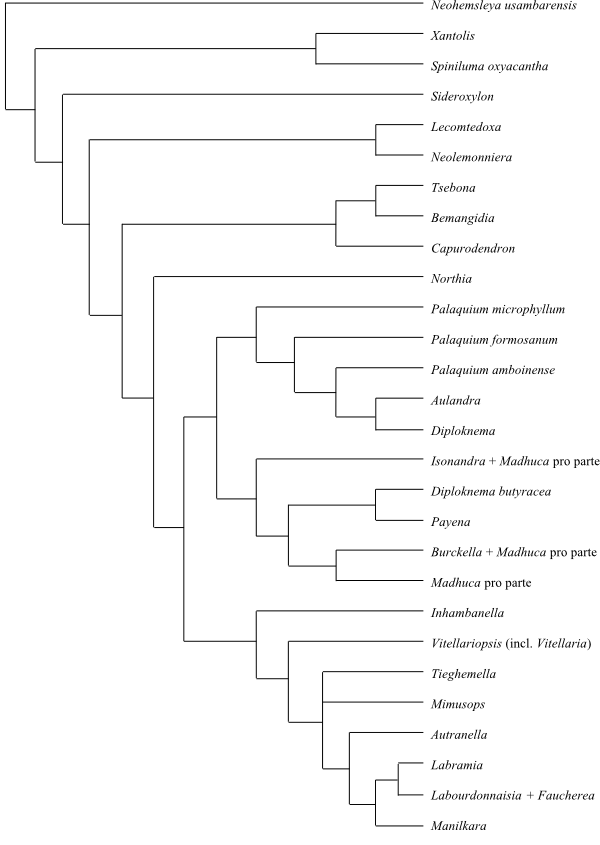

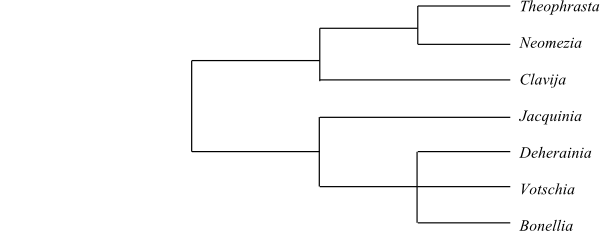

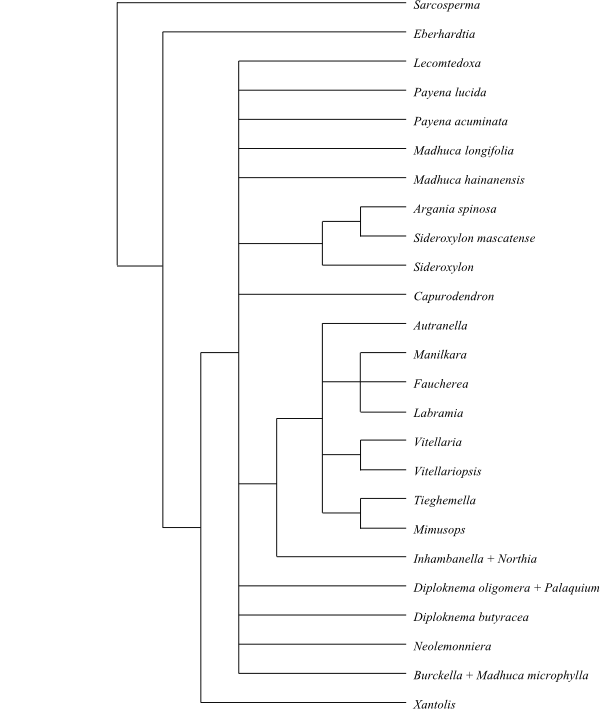

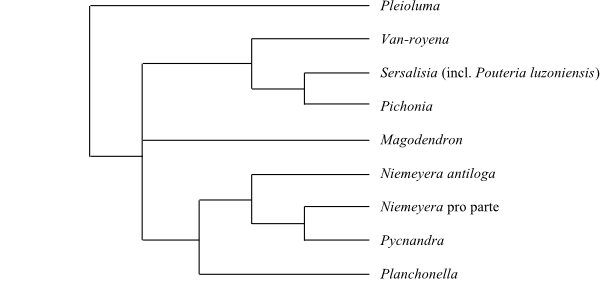

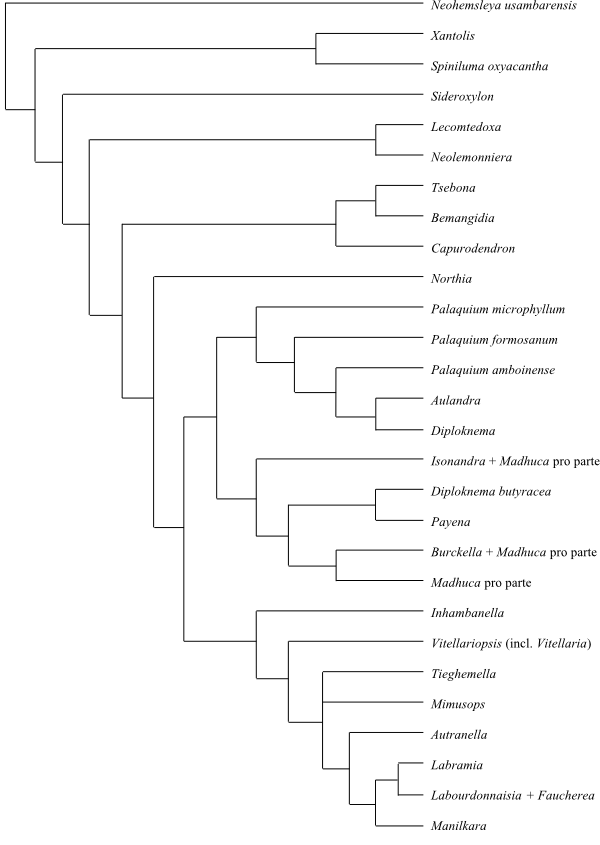

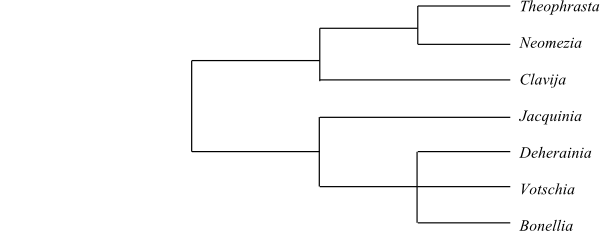

The second clade in this trichotomy has the

following topology: [Sapotaceae+ [Ebenaceae+[Maesaceae+[[Theophrastaceae+Samolaceae]+[Myrsinaceae+Primulaceae]]]]]. Morphological and

phytochemical characters supporting this clade are few: connate petals;

apotropous ovules; and absence of ellagic acid. Furthermore, bitegmic ovules

and inner integument thicker than outer are two potential synapomorphies

uniting Ebenaceae with the

following clade. [Maesaceae+[[Theophrastaceae+Samolaceae]+[Myrsinaceae+Primulaceae]]] is a very strongly

supported clade. Synapomorphies are, e.g., the following (Stevens 2001

onwards): schizogenous secretory canals with yellow, red or brown substances

(e.g. tannins) sometimes present; nodes 3:3?; stomata sometimes anisocytic;

presence of small immersed and often peltate glandular hairs; inflorescence

racemose; petals and stamens arising from common primordia; presence of

nectaries; stamens as many as petals, antepetalous; staminodia antesepalous,

represented by at least a vascular trace; carpels five, antepetalous; style

short, hollow; stigma capitate; placentation free central, with large placenta;

ovules at least partially immersed in swollen placenta, apotropous, bitegmic;

micropyle bistomal; endosperm development nuclear; tanniniferous endothelium

present; seeds angular; endotesta crystalliferous; endosperm copious, sometimes

with amyloid (xyloglucans) or hemicellulose, and sometimes with thick and

pitted cell walls.

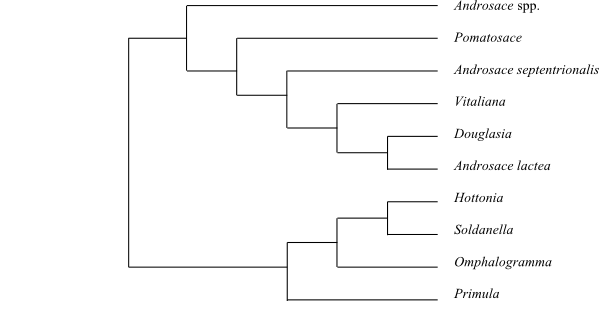

The clade [[Theophrastaceae+Samolaceae]+[Myrsinaceae+Primulaceae]] is characterized by

wood rays at least 5-seriate; absence of uniseriate rays in woody species;

presence of small immersed often peltate or glandular hairs; absence of floral

prophylls (bracteoles); corolla subrotate, with imbricate aestivation; corolla

tube fairly short; petals arising abaxially from common primordium; and

staminal primordium larger than petal primordium. Theophrastaceae and

Samolus share the characters bracts displaced up pedicels and presence

of petaloid staminodia, whereas Myrsinaceae och Primulaceae share two identical

deletions in plastid genendhF.

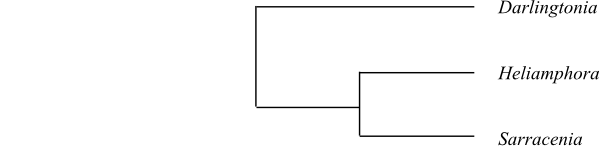

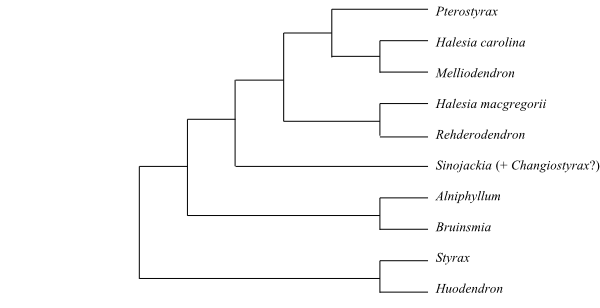

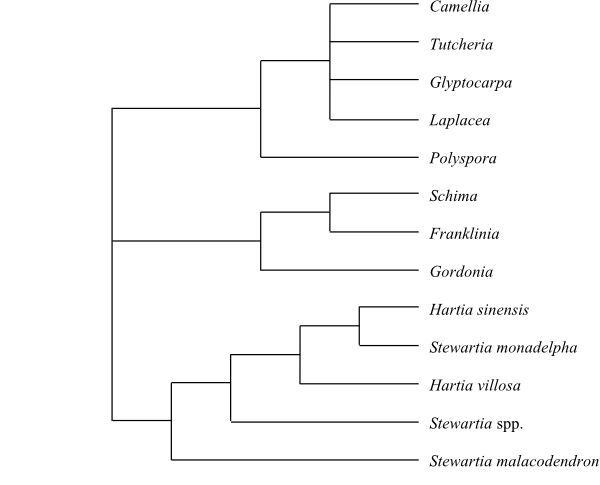

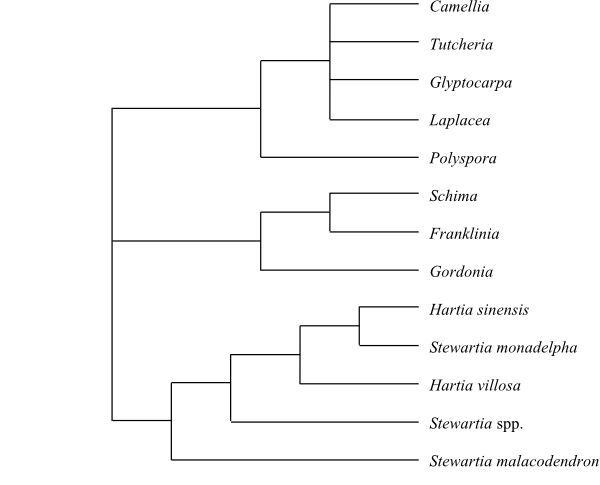

The third clade of the trichotomy comprises (1)

Theaceae, (2) the clade [Symplocaceae+ [Styracaceae+Diapensiaceae]] and (3) the clade

[Sarraceniaceae+[Actinidiaceae+Roridulaceae]]+ [Clethraceae+[Cyrillaceae+Ericaceae]] and may be characterized

by the synapomorphies: vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates, and

serrate leaves. An additional lineage is the mycotrophical holoparasitic

Mitrastemma although with a highly uncertain position.

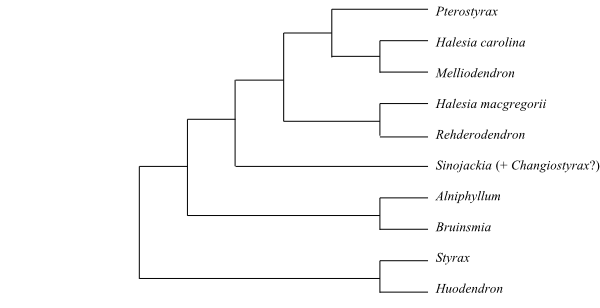

The clade [Symplocaceae+[Styracaceae+Diapensiaceae]] is characterized

by the features: woody habit; racemose inflorescence; hollow style; and copious

endosperm. The lineage [Styracaceae+Diapensiaceae] has pericyclic

phellogen; nodes 1:1; absence of glandular hairs; spiral leaves with usually

serrate margin; nectariferous disc absent or poorly developed and annular;

stamens usually twice as many as petals; filaments connate at base or adnate to

corolla tube; anthers basifixed, introrse, longicidal; endothecium well

developed and with fibrous thickenings; pollen grains tricolporate, shed as

monads and usually bicellular at dispersal; pistil composed of two to four

carpels; hollow style continuing without interruption into locules; ovules

numerous per carpel; unitegmic, tenuinucellar; megagametophyte usually with

large amount of starch; endosperm development cellular; and fruit usually a

loculicidal capsule. Furthermore, calciumoxalate crystals are often present as

aggregations in idioblasts in the parenchyma.

The [[Sarraceniaceae+[Actinidiaceae+Roridulaceae]]+[Clethraceae+[Cyrillaceae+Ericaceae]]] clade has the potential

synapomorphies (Stevens 2001 onwards): inflorescence racemose; anthers

extrorse, inverting during development, and dehiscing by apical pores or short

slits; pollen grains rugulate; tectum and foot layer solid; infratectum

granular; pistil composed of three carpels, with median carpel adaxial, or five

antepetalous carpels; style impressed into ovary apex; ovules numerous per

carpel; endothelium present; fruit a capsule; exotesta with strongly thickened

inner cell walls; endosperm copious; and absence of mitochondrial intron

coxII.i3. The clade [Sarraceniaceae+[Actinidiaceae+Roridulaceae]] is characterized by

the features: absence of nectary; stigma Dry type; presence of hypostase; and

presence of Route I secoiridoids. The lineage [Clethraceae+[Cyrillaceae+Ericaceae]] has the synapomorphies:

phellogen pericyclic; absence of pericyclic fibres; leaves spiral;

inflorescence racemose; absence of floral prophylls; flowers pendulous; basal

part of ovary wall nectariferous; stamens twice as many as sepals; style

hollow; endosperm with micropylar and chalazal haustoria; testa reduced; embryo

terete; and presence of ellagic acid. Finally, Cyrillaceae and Ericaceae share the synapomorphies:

presence of colleters; connate petals; stigma Wet type; and presence of

myricetin.

The strongly supported clade [[Sarraceniaceae+[Actinidiaceae+Roridulaceae]]+[Clethraceae+[Cyrillaceae+Ericaceae]]] has the potential

synapomorphies (Stevens 2001 onwards; Löfstrand & Schönenberger 2015):

inflorescence racemose; anthers attached adaxially, extrorse, inverting during

development, and dehiscing by apical pores or short slits; pollen grains

rugulate; tectum and foot layer solid; infratectum granular; depression at

ovary-to-style transition; pistil composed of three carpels, with median carpel

adaxial, or five antepetalous carpels; style impressed into ovary apex; ovules

numerous per carpel; endothelium present; fruit a capsule; exotesta with

strongly thickened inner cell walls; endosperm copious; and absence of

mitochondrial intron coxII.i3. The clade [Sarraceniaceae+[Actinidiaceae+Roridulaceae]] is characterized by

features such as: petals thick to massive; nectary absent; polystemony; stigma

Dry type; hypostase present; and Route I secoiridoids present. The lineage

[Actinidiaceae+Roridulaceae] is characterized by,

e.g.: presence of calcium oxalate raphides; mucilage cells; inner gynoecium

surface secretory; and synlateral vasculature absent from ovary. The clade

[Clethraceae+[Cyrillaceae+Ericaceae]] has the synapomorphies:

phellogen pericyclic; absence of pericyclic fibres; leaves spiral;

inflorescence racemose; absence of floral prophylls; flowers pendulous;

androecium two-worled; basal part of ovary wall nectariferous; stamens twice as

many as sepals; style hollow; endosperm with micropylar and chalazal haustoria;

testa reduced; embryo terete; and presence of ellagic acid. Finally, Cyrillaceae and Ericaceae share the synapomorphies:

presence of colleters; connate petals; stigma Wet type; and presence of

myricetin.

ACTINIDIACEAE Gilg et

Werderm.

|

( Back to Ericales )

|

Gilg et Werdermann in Engler et Prantl, Nat.

Pflanzenfam., ed. 2, 21: 36. Dec 1925, nom. cons.

Saurauiaceae Griseb.,

Grundr. Syst. Bot.: 98. 1-2 Jun 1854 [’Sauraujeae’], nom. cons.;

Actinidiales Takht. ex Reveal in Phytologia 74: 174.

25 Mar 1993

Genera/species 3/360

Distribution Tropical and

subtropical regions of East and Southeast Asia, the Himalayas, Malesia to New

Guinea, northeastern Queensland, Solomon Islands, Fiji, Mexico, Central

America, the Andes to Chile.

Fossils Late Cretaceous

records of Actinidiaceae

are known from North America and Europe and they are found at many Cenozoic

sites in the Northern Hemisphere. Saurauia alenae and S.

antiqua, anatropous seeds with reticulate surface, have been found in the

Late Turonian to the Maastrichtian of Central Europe, and fossils similar to

Actinidia are recorded from the Late Eocene onwards.

Actinidiophyllum has been described from Cenozoic strata in Japan.

Parasaurauia allonensis and Glandulocalyx, represented by

flowers with free pentamerous perianth, ten stamens in two series and three

carpels with free styles, was described from the Late Cretaceous (Late

Santonian/Early Campanian) of Georgia in the United States as sister-group to

[Actinidia+Saurauia] (Keller & al. 1996). Leaf

impressions resembling Saurauia are known from mid-Eocene layers of

North America.

Habit Bisexual,

morphologically dioecious (Clematoclethra), functionally dioecious or

monoecious, evergreen or deciduous trees, shrubs or lianas.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

ab initio superficially or deeply seated. Medulla often septate by diaphragms.

Endodermis prominent. Pericycle with continuous ring of sclerenchyma. Vessel

elements dimorphic, with scalariform or simple (sometimes reticulate)

perforation plates; lateral pits usually opposite (sometimes scalariform or

alternate), simple or bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements

tracheids or fibre tracheids with bordered pits, non-septate. Wood rays

uniseriate or multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal

diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal scanty vasicentric or banded.

Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes usually 1:1, unilacunar with one leaf trace

(rarely 3:3, trilacunar with three traces). Parenchyma with idioblasts (raphide

cells) containing raphides; calciumoxalate as crystal sand present in at least

Clematoclethra.

Trichomes Hairs multicellular,

uniseriate, often bristle-like or flattened, or branched, stellate or

dendritic; glandular hairs, short and long, sometimes present.

Leaves Usually alternate

(spiral; rarely opposite), simple, entire, with conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules

very small and caducous or absent; leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle

transection deeply arcuate with wing bundles (Actinidia), or annular

(sometimes with medullary bundles). Venation usually pinnate, camptodromous

(sometimes subpalmate); some veins proceeding into teeth. Stomata usually

anomocytic (sometimes paracytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids as platelets or

transversely ridged rodlets. Mesophyll with calciumoxalate raphides. Leaf

margin usually serrate (sometimes entire); tooth apices widened, translucent,

persistent.

Inflorescence Axillary,

usually thyrsopaniculate etc. (flowers sometimes solitary, axillary). Floral

prophylls (bracteoles) present or absent.

Flowers Actinomorphic.

Hypogyny. Sepals (three to) five (to eight), with imbricate quincuncial

aestivation, usually persistent, free. Petals (three to) five (to nine), with

imbricate quincuncial aestivation, caducous, free or connate at base, sometimes

nectariferous at base. Nectary usually absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens c. 20 to c.

240 (in Clematoclethra ten), in two or more whorls (primarily

diplostemonous), usually inflexed in bud (not in Saurauia), sometimes

in five antepetalous fascicles. Filaments usually free (rarely connate at

base), usually free from petals (sometimes epipetalous). Anthers dorsifixed,

versatile, late inverted (finally resupinate), tetrasporangiate, extrorse,

longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal or short slits widening at apex) or

poricidal (dehiscing by seemingly subapical pores). Tapetum secretory, with

multinucleate cells (sometimes with fused nuclei). Female flowers sometimes

with staminodia?

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tricolporate (sometimes

tetracolporate), usually shed as monads (rarely tetrads), bicellular at

dispersal. Exine tectate, with granular infratectum, imperforate, psilate,

microgranulate or rugulate, often transversely striate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

(three to) five to c. 20 incompletely connate synascidiate carpels. Ovary

superior, (trilocular to) quinquelocular to 20-locular (sometimes incompletely

septate). Stylodia (three to) five to c. 20, short, free or partially connate,

sometimes impressed, sometimes persistent, or style single, simple and hollow

(Clematoclethra; in Actinidia furrowed). Stigmas capitate,

peltate or lobate, papillate, Dry type. Male flowers sometimes with

pistillodia?

Ovules Placentation axile.

Ovules usually numerous (in Clematoclethra approx. ten) per carpel,

anatropous, unitegmic, tenuinucellar. Integument six to nine cell layers thick.

Hypostase well developed. Parietal tissue approx. three cell layers thick.

Nucellar cap approx. three cell layers thick. Megasporocytes usually one

(occasionally several, archespore multicellular). Megagametophyte monosporous,

Polygonum type. Endosperm development cellular. Endosperm haustoria?

Embryogenesis solanad. Polyembryony often occurring.

Fruit Usually a berry

(sometimes a loculicidal capsule), often with persistent calyx; seeds embedded

in pulp formed by placentae.

Seeds Aril usually absent

(present in Actinidia). Testa multiplicative. Exotesta with inner cell

walls of outer epidermis thick, with theoid exotestal thickenings. Endotesta?

Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, oily or proteinaceous. Embryo

large, usually straight (sometimes curved), well differentiated, without

chlorophyll. Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 20, 24, 29, 30,

39 (x = 12 in Clematoclethra; x = 13 in Saurauia; x = 29 in

Actinidia) – Polyploidy frequently occurring.

DNA Horizontal transfer of

mitochondrial gene rps2 in Actinidia. Mitochondrial intron

coxII.i3 lost.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin?), catechins, Route I secoiridoids, Group X

secoiridoids (nepetalactones, iridoidpyridine alkaloids), gallic acid,

proanthocyanidins (cyanidin, prodelphinidin), and polyacetate-derived

arthroquinones present. Actinidin (a proteinase) present in Actinidia.

Alkaloids usually absent (matatabi lactone and actinidine present). Ellagic

acid, saponins, and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Ornamental plants,

fruits.

Systematics

Clematoclethra (1; C. scandens; western and central China),

Actinidia

(c 60; southern and eastern China, the Korean Peninsula, Japan, Siberia,

Southeast Asia), Saurauia (c 300; tropical Asia, the Himalayas,

tropical and subtropical regions of East and Southeast Asia, Malesia to New

Guinea, northeastern Queensland, Solomon Islands, Fiji, Mexico and Central

America, northern Andes to Chile).

Actinidiaceae are sister-group to

Roridula

(Roridulaceae).

Clematoclethra differs from Actinidia

and Saurauia, e.g., in having ten (instead of numerous) stamens and a

single hollow style, and in being morphologically dioecious. The topology

[Clematoclethra+[Actinidia+Saurauia]]

was suggested by Friis & al. (2011). Two geographical lineages were

identified by Löfstrand & Schönenberger (2015) in Saurauia. One

lineage is characterized by choripetaly and free styles, whereas the second

lineage has sympetaly and partially united styles. Gynoecium merism and base

chromosome numbers are additional characters.

BALSAMINACEAE A.

Rich.

|

( Back to Ericales )

|

Richard in J. B. G. M. Bory de Saint-Vincent,

Dict. Class. Hist. Nat. 2: 173. 31 Dec 1822 [’Balsamineae’], nom.

cons.

Balsaminales Bercht.

et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 221. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Balsamineae’];

Hydroceraceae Wilbrand, Nat. Pflanzenfam.: 26.

Mai-Dec 1834 [’Hydrocereae’], nom. illeg.;

Impatientaceae Lem., Ill. Hort. 1: ad t. 9. Mar 1854

[’Impatientiaceae’]; Balsaminineae

Engl., Syllabus, ed. 2: 146. Mai 1898; Balsaminanae

Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.: xliv. 23 Dec 2001

Genera/species 2/>1.000

Distribution Tropical and

subtropical Africa, Madagascar, tropical Asia to New Guinea, with their largest

diversity in Madagascar and Southeast Asia, few species in temperate parts of

Eurasia, Africa and North America.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, although

usually functionally monoecious due to extreme protandry, usually perennial or

annual herbs (rarely partially woody). Stem more or less succulent, often

almost translucent. Impatiens tuberosa and the epiphytic I.

etindensis with large stem tubers. Numerous species are helophytes.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen?

Primary vascular tissue a cylinder of vascular bundles. Secondary lateral

growth usually absent. Wood paedomorphic. Vessels solitary. Vessel elements

with simple perforation plates, lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem

elements? Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes

1:1, unilacunar with one leaf trace. Sclerenchyma and sclereids absent.

Idioblasts with mucilage present. Cortex with calciumoxalate raphides in raphid

sacs.

Trichomes Hairs usually

absent.

Leaves Usually alternate

(spiral; rarely opposite or verticillate), simple, entire, with involute

ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole often with glands (rarely with

extrafloral nectaries or foliaceous outgrowths at leaf base, petiole or stem).

Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate. Venation pinnate. Stomata usually

anomocytic (sometimes almost anisocytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids?

Hydathodes abundant. Mesophyll with calciumoxalate raphides. Leaf margin

usually serrate (sometimes crenate or entire); teeth apiculate, basal teeth

often with nectariferous glands.

Inflorescence Axillary, raceme

or umbel-like. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) sometimes absent.

Flowers Zygomorphic, usually

resupinate (inverting during growth). Hypogyny. Sepals usually three (sometimes

five), with imbricate aestivation, caducous, free, two lateral abaxial sepals

reduced and small or absent, median adaxial sepal petaloid, usually with

nectariferous spur (absent in some Malagasy species) with secretory cells on

inner side, two abaxial/upper sepals very small or absent. Petals five, unequal

in size, with imbricate aestivation, dorsal petal free, flat or cucullate, four

lower/lateral petals usually pairwise connate (in Hydrocera free);

when three sepals, then adaxial petal often with sepaloid keel. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens five,

haplostemonous, antesepalous, alternipetalous. Filaments short, stout, connate

at apex and forming ring around gynoecium, upper filaments slightly longer than

lower ones, free from tepals. Anthers ab initio connate into cucullate calyptra

above stigma, finally coming loose at base and uplifted by accrescent

gynoecium, dorsifixed to subbasifixed, non-versatile, usually dithecal

(sometimes polythecal and septate by transverse trabeculae), tetrasporangiate,

introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory.

Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains 3(–5)-colpate or

3(–5)-porate, starchy, shed as monads, usually bicellular (rarely

tricellular) at dispersal. Exine semitectate, with granular infratectum,

reticulate; with raphides and with cellulose threads adhering pollen grains to

anther.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

(four or) five connate antepetalous carpels; when carpels four, then adaxial

carpel larger. Ovary superior, (quadrilocular or) quinquelocular. Style single,

very short, or absent. Stigmas usually one or (four or) five, relatively wide,

non-papillate, Wet type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation axile.

Ovules usually numerous (in Hydrocera one to three) per carpel,

usually anatropous (rarely hemitropous), pendulous, apotropous, usually

(incompletely) bitegmic (sometimes unitegmic), incompletely tenuinucellar.

Micropyle endostomal. Outer integument four to ten cell layers thick (in

Hydrocera six to eight cell layers thick). Inner integument three to

six cell layers thick. Micropylar epistase present. Megagametophyte usually

monosporous, Polygonum type (sometimes disporous, 8-nucleate,

Allium type), finally strongly prolonged. Endosperm development

helobial (cellular?). Endosperm haustorium chalazal (in Hydrocera also

micropylar). Embryogenesis onagrad.

Fruit Usually a loculicidal

and septifragal carnose explosion capsule, dehiscing by capsule walls rolling

in from base due to tensions in fleshy convex fruit wall; tensions liberated at

slightest touch by bursting of wall along septa (in Hydrocera a

drupaceous schizocarp with hard endocarp splitting into five mericarps each

with one seed and two air chambers).

Seeds Seed pachychalazal. Seed

mucilaginous hairs sclerotized, with spiral thickenings. Aril? Calciumoxalate

raphide bundles abundant. Exotesta lignified, thickened. Mesotesta crushed.

Endotesta? Tegmen? Testa in Hydrocera sclerotized, consisting of six

to eight layers of thickened cells and five layers of unthickened cells.

Perisperm not developed. Endosperm thin, rich in lipids, poor in starch. Embryo

large, straight, well differentiated, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two,

large, planoconvex. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = (3–)7–10 (or

more, up to 33; Impatiens), n = 8 (Hydrocera)

DNA Intron present in

mitochondrial gene coxII.i3. Duplication of class B DEF

genes.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin?), cyanidin, non-hydrolyzable tannins,

proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins), and naphthoquinones and their derivatives

(e.g. lawsone) present. Ellagic acid, alkaloids, saponins, and cyanogenic

compounds not found. Seed oils with glycerides of acetic acid and parinaric

acid. Xyloclucans sometimes present in endosperm.

Use Ornamental plants.

Systematics Hydrocera

(1; H. triflora; India, Indochina); Impatiens

(>1.000; tropical and subtropical Africa, Madagascar, tropical Asia to

southern China and New Guinea, with their largest diversity in Madagascar and

mountain regions in India and Southeast Asia, few species in temperate parts of

Eurasia, Africa and North America).

Balsaminaceae are probably sister

to Tetrameristaceae.

CLETHRACEAE

Klotzsch

|

( Back to Ericales )

|

Klotzsch in Linnaea 24: 12. Mai 1851, nom.

cons.

Genera/species 2/90–95

Distribution Madeira, East

Asia to the Korean Peninsula, Japan and Taiwan, Hainan, Southeast Asia, Malesia

to New Guinea, eastern and southeastern United States, Mexico, tropical

America.

Fossils Two species of

Clethra are known from the Miocene of Europe. In addition several

fossilized capsules from Maastrichtian sediments in Europe have been assigned

to Clethraceae, although

their systematic affiliation may be questioned, such as Disoclethra

with three species, Purdiaeopsis campanulatus and

Valvaecarpus with four species. A fossil flower, Glandulocalyx

upatoiensis, from the Santonian of Georgia has been attributed to Actinidiaceae or Clethraceae by Schönenberger &

al. (2012).

Habit Bisexual (rarely

functionally gynodioecious), evergreen or deciduous trees or shrubs.

Vegetative anatomy Arbuscular

mycorrhiza present. Phellogen ab initio pericyclic. Stem in Clethra

with prominent endodermis and heterogeneous medulla. Vessel elements with

scalariform perforation plates (often with numerous cross-bars); lateral pits

opposite or alternate, bordered pits. Vestured pits sometimes present.

Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids or fibre tracheids with bordered

pits, non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial

parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal

scanty. Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes 1:1, unilacunar with one leaf trace.

Raphide cells absent.

Trichomes Hairs multicellular,

uniseriate or tufted and/or stellate.

Leaves Alternate (spiral),

simple, entire, sometimes coriaceous, with conduplicate-subplicate ptyxis.

Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate or

annular; petiole with medullary bundle. Venation pinnate, eucamptodromous,

brochidodromous or semicraspedodromous (in Purdiaea acrodromous to

palinactinodromous). Stomata anomocytic, anisocytic, paracytic or actinocytic.

Cuticular wax crystalloids? Domatia as hair tufts present in some species.

Petiole and phloem with secretory cells. Calciumoxalate druses abundant. Leaf

margins usually serrate or glandular serrate (sometimes entire).

Inflorescence Terminal or

axillary, simple racemes, or paniculate, fasciculate or umbel-like cymose.

Bracts often caducous (in Purdiaea large). Floral prophylls

(bracteoles) absent.

Flowers Actinomorphic or

slightly zygomorphic, small. Pedicel articulated. Hypogyny. Sepals five (or

six), with imbricate quincuncial aestivation, persistent, free or partially

connate, sometimes unequal in length. Petals five (or six), with imbricate

quincuncial aestivation, caducous, usually free (rarely connate below). Ovary

base often nectariferous. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens usually 5+5

(rarely 6+6; in Purdiaea with outer stamens alternipetalous),

diplostemonous (often secondarily obdiplostemonous). Filaments free from each

other, usually free from tepals (sometimes adnate to petal bases). Anthers

bilobate-sagittate to caudate (seemingly apically prolonged), ventrifixed

(dorsifixed?), versatile, late inverted (finally resupinated),

tetrasporangiate, at anthesis inverted from extrorse to introrse, poricidal

(dehiscing by seemingly apical pores or short slits). Tapetum secretory, with

binucleate cells. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tricolporate, shed as

monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with granular infratectum,

rugulate or psilate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

three (to five) connate carpels. Ovary superior, usually trilocular (rarely

quadri- or quinquelocular). Style single, simple. Stigma simple or usually

trilobate (rarely quadri- or quinquelobate), papillate, Dry type. Pistillodium

absent.

Ovules Placentation usually

axile (in Purdiaea apical). Ovules few to numerous (in

Purdiaea one) per carpel, usually anatropous (in Purdiaea

orthotropous, pendulous), unitegmic, tenuinucellar. Integument ? cell layers

thick (in Purdiaea gradually degenerating). Megagametophyte

monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development cellular. Endosperm

haustoria chalazal and micropylar. Embryogenesis asterad.

Fruit Usually a loculicidal

capsule, sometimes with persistent calyx (in Purdiaea a nut).

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat

often winged. Testa consisting of thin exotesta, with theoid exotestal

thickenings (testa in Purdiaea indistinct, disappearing). Perisperm

not developed. Endosperm copious, fleshy, oily and with hemicellulose. Embryo

short, straight, well differentiated, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two, short.

Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 8 – Polyploidy

occurring.

DNA Mitochondrial intron

coxII.i3 lost.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(quercetin), cyanidin, triterpenes, ellagic and gallic acids, and

proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidin) present. Iridoids? Alkaloids and cyanogenic

compounds not found. Carbohydrates stored as oligosaccharides with kestose or

isokestose bonds.

Use Ornamental plants, timber,

carpentries.

Systematics Clethra

(80–85; China, the Korean Peninsula, Japan, Taiwan, Southeast Asia, Malesia

to New Guinea, eastern and southeastern United States [C. alnifolia],

Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America, one species,

C. arborea, on Madeira), Purdiaea (12; southeastern United

States, Central America, Cuba, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, with their highest

diversity on Cuba).

Clethraceae are sister-group to

[Cyrillaceae+Ericaceae].

Species delimitation in Clethra

is difficult. Clethra arborea (Madeira) may be sister to C.

alnifolia of eastern North America.

CYRILLACEAE (Torr. et

A. Gray) Lindl.

|

( Back to Ericales )

|

Lindley, Veg. Kingd.: 445. 14-28 Mar 1846, nom.

cons.

Cyrillales Doweld,

Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.: xliv. 23 Dec 2001

Genera/species 2/2

Distribution Coastal plains in

southeastern United States, the West Indies, Central America, northern South

America.

Fossils Fossil wood and pollen

grains assigned to Cyrilla are found in Oligocene layers in North

America. Cenozoic brown coal in western Europe contains fossil wood similar to

that in Cyrilla. The fossil fruits of Epacridicarpum from the

Late Cretaceous and the Cenozoic of Europe have also been assigned to Cyrillaceae, but this systematic

placement is doubtful.

Habit Bisexual, evergreen or

deciduous shrubs or small trees.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

ab initio pericyclic. Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates;

lateral pits scalariform or opposite, bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary

xylem elements tracheids or fibre tracheids with bordered pits, non-septate.

Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma

apotracheal diffuse. Sieve tube plastids Pcf type (with protein crystals and

fibrils, but no starch). Nodes 1:1, unilacunar with one leaf trace. Raphid

cells absent. Wood ray cells sometimes with prismatic calciumoxalate

crystals.

Trichomes Hairs absent.

Leaves Alternate (spiral),

simple, entire, sometimes coriaceous, with supervolute ptyxis. Stipules and

leaf sheath absent; lateral or sublateral red or blackish ligulate? glandular

structures – colleters – at buds and bracts may be reduced stipules.

Petiole vascular bundle transection annular, complex or deeply concave.

Venation pinnate. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Epidermis

with or without mucilage cells. Mesophyll with calciumoxalate as druses and

solitary prismatic crystals. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal or

axillary, racemes. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) absent?

Flowers Actinomorphic

(occasionally slightly zygomorphic). Hypogyny. Sepals five (to seven), with

open (or imbricate quincuncial) aestivation, unequal in size, persistent,

connate at base. Petals five (to seven), with imbricate quincuncial

aestivation, free or connate at base, in Cyrilla nectariferous. Disc

intrastaminal (in Cliftonia with nectaries?).

Androecium Stamens five (to

seven), haplostemonous, antesepalous (inner whorl absent; Cyrilla), or

(5+5) 6+6 or 7+7, diplostemonous (Cliftonia). Filaments free from each

other and from tepals. Anthers dorsifixed, not inverted at anthesis, versatile,

tetrasporangiate, introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits).

Tapetum secretory, with binucleate cells. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains 3(–6)-colporate, shed as

monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with granular infratectum,

microperforate, smooth.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

(two to) five connate carpels. Ovary superior, (bilocular to) quinquelocular.

Basal part of ovary wall nectariferous? Style single, simple, very short, or

absent. Stigma punctate or (bilobate to) quinquelobate, non-papillate, Dry

type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation axile or

apical. Ovules one to three per carpel, anatropous, pendulous, usually

apotropous, unitegmic, tenuinucellar. Integument four to seven cell layers

thick, sometimes vascularized, gradually degenerating. Megagametophyte

monosporous, Polygonum type (in at least Cliftonia sometimes

also aposporous Hieracium type). Antipodal cells persistent. Endosperm

development cellular. Endosperm haustoria chalazal and micropylar.

Embryogenesis?

Fruit A one- to four-seeded

dry drupe or a one-seeded two- to five-winged samara, often with persistent and

accrescent calyx. Pericarp with tannins and druses.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa

indistinct, early disappearing, with theoid exotestal thickenings? Perisperm

not developed. Endosperm moderately developed, fleshy. Embryo large, straight,

well differentiated, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two, small. Germination

phanerocotylar?

Cytology n = 20

DNA

Phytochemistry Insufficiently

known. Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), cyanidin, and ellagic acid

(Cyrilla) present. Alkaloids and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Condensed and hydrolyzable tannins? Iridoids?

Use Ornamental plants.

Systematics Cyrilla

(1; C. racemiflora; southeastern United States to northern South

America), Cliftonia (1; C. monophylla; southeastern United

States).

Cyrillaceae are sister to Ericaceae.

DIAPENSIACEAE (Link)

Lindl.

|

( Back to Ericales )

|

Lindley, Intr. Nat. Syst. Bot., ed. 2: 233. 13

Jun 1836, nom. cons.

Galacinaceae D. Don

in Edinburgh New Philos. J. 6: 53. Oct-Dec 1828 [’Galacinae’];

Diapensiineae Link, Handbuch 1: 595. Jan-Aug 1829

[‘Diapensiaceae’];

Diapensiales Engl. et Gilg in Engler, Syllabus, ed.

9-10: 314. Nov-Dec 1924; Diapensianae Doweld, Tent.

Syst. Plant. Vasc.: xlv. 23 Dec 2001

Genera/species 5/12

Distribution Cold-temperate

and arctic-alpine regions on the Northern Hemisphere, the Himalayas, eastern

Tibet, western China, northern Burma, Japan, Taiwan, southeastern United

States.

Fossils Uncertain.

Actinocalyx bohrii was described from the Late Cretaceous of southern

Sweden. It had separate stylodia and the pollen grains were smaller than in

extant Diapensiaceae.

However, the systematic affiliation is questioned (Martínez-Millán 2010).

Habit Bisexual, evergreen

dwarf shrubs or perennial herbs.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza

ectotrophic and endotrophic. Phellogen ab initio usually pericyclic (sometimes

superficial). Pericyclic fibres usually absent (present in Shortia).

Vessel elements usually with simple (sometimes scalariform) perforation plates;

lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements ? with bordered pits. Wood

rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes usually 3:3,

trilacunar with three leaf traces (in Pyxidanthera 1:1, unilacunar

with one trace). Calciumoxalate crystals (single or compound) sometimes

present.

Trichomes Hairs absent

(always?); glandular hairs absent.

Leaves Alternate (spiral),

simple, entire, coriaceous, with ? ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent.

Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate to annular; medullary bundles

sometimes present. Venation pinnate to palmate or leaves uninerved, in

Diapensia and Pyxidanthera inverted eucamptodromous (lateral

veins curved at base, narrowing without fusing with main vein or other lateral

veins), in Galax and Shortia actinodromous or camptodromous,

in Berneuxia brochidodromous; secondary veins subpinnate to palmate.

Stomata usually anomocytic, without subsidiary cells (rarely anisocytic).

Cuticular wax crystalloids? Calciumoxalate as groups of crystals or single

crystals (Galax). Leaf margin serrate or entire.

Inflorescence Terminal,

raceme-like cymose, or flowers solitary terminal (sometimes axillary).

Flowers Actinomorphic.

Hypogyny. Sepals five, with imbricate aestivation, persistent, free or connate

into tube. Petals five, usually with imbricate (rarely contorted) aestivation,

caducous, usually connate below (in Galax free or almost free),

sometimes dentate at apex. Basal part of ovary in some species

nectar-producing. Disc absent or strongly reduced.

Androecium Stamens five,

haplostemonous, antesepalous, alternipetalous. Filaments flattened, usually

free (in Galax connate at base), at least outer staminal whorl

epipetalous. Anthers usually basifixed (or transverse with horizontal thecae),

incurved (inverted during development, base becoming directed upwards),

non-versatile, in Galax and Pyxidanthera with basal

appendages, usually tetrasporangiate (in Galax disporangiate),

introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal [Berneuxia,

Diapensia, Shortia] or transverse [Galax,

Pyxidanthera] slits). Tapetum secretory, with binucleate cells.

Staminodia absent in Diapensia and Pyxidanthera; in

Berneuxia, Galax and Shortia five epipetalous

antepetalous inner staminodia alternating with five fertile outer

(alternipetalous) stamens.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains tri- or hexacolp(oroid)ate, shed

as monads, tricellular (bicellular?) at dispersal. Exine semitectate, with

columellate infratectum, reticulate, or intectate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

three connate carpels; median carpel adaxial. Ovary superior, trilocular,

sometimes nectariferous. Style single, usually simple (in Diapensia

trilobate), hollow (with stylar canal). Stigma usually single, shortly trifid

(stigmas in Diapensia capitate), non-papillate, Wet type. Pistillodium

absent.

Ovules Placentation usually

axile (sometimes parietal). Ovules several to numerous per carpel, usually

anatropous (sometimes hemianatropous or campylotropous), unitegmic,

tenuinucellar. Integument five to seven cell layers thick. Megagametophyte

monosporous, Polygonum type (in at least Pyxidanthera with

large amount of starch). Synergids in Diapensia with a filiform

apparatus. Antipodal cells sometimes proliferating (in Shortia up to

c. 40 cells), persistent. Endosperm development cellular. Endosperm haustoria

absent. Embryogenesis solanad?

Fruit A loculicidal

capsule.

Seeds Aril absent? Exotesta

two or three cell layers thick, with thick inner cell walls, with theoid

exotestal thickenings. Endotesta? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious,

fleshy, containing lipids. Embryo relatively large, straight to somewhat

curved, well differentiated, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Germination?

Cytology n = 6 (tetraploidy

occurring in Galax urceolata)

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin, gossypetin), ellagic and gallic acids present. Ursolic

acid, proanthocyanidins, alkaloids, and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Iridoids? Aluminium accumulated.

Use Ornamental plants.

Systematics Galax (1;

G. urceolata; in and near the Appalachian Mountains in eastern United

States), Pyxidanthera (1; P. barbulata; coastal regions in

eastern United States), Diapensia

(4; D. lapponica: arctic-alpine Europe; D. himalaica: the

Himalayas, Burma, Yunnan, Xizang; D. purpurea: Yunnan, Sichuan; D.

wardii: southeastern Xizang), Berneuxia

(1; B. thibetica; eastern Himalayas, western China), Shortia

(5; S. exappendiculata: Taiwan; S. galacifolia: the

Appalachian Mountains in southeastern United States; S. sinensis:

China; S. soldanelloides, S. uniflora: to Japan,

Yakushima).

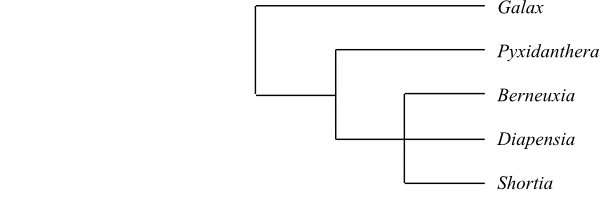

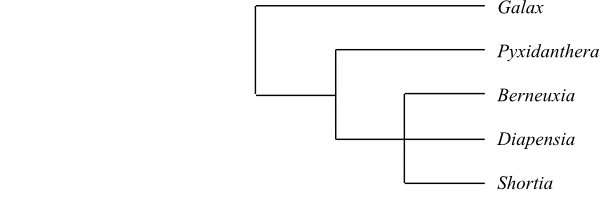

Diapensiaceae may be sister to

Styracaceae, although the

support is sometimes fairly weak.

Galax and Pyxidanthera are

successive sister-groups to the remaining Diapensiaceae.

|

Cladogram of Diapensiaceae based on

DNA sequence data and morphology (Rönblom & Anderberg 2002).

|

Gürcke in Engler et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam.,

IV, 1: 153. Dec 1891, nom. cons.

Guaiacanaceae Juss.,

Gen. Plant.: 155. 4 Aug 1789 [’Guiacanae’];

Diospyraceae Vest, Anleit. Stud. Bot.: 271, 294. 1818

[’Diospyroideae’]; Diospyropsida

Brongn., Enum. Plant. Mus. Paris: xxi, 72. 12 Aug 1843

[’Diospyroideae’]; Diospyrales Prantl,

Lehrb. Bot.: 216. 20 Apr 1874 [’Diospyrinae’];

Ebenales Engl., Syllabus: 155. Apr 1892;

Ebenineae Bessey in C. K. Adams, Johnson’s

Universal Cyclop. 8: 463. 15 Nov 1895 [‘Ebenales’];

Diospyrineae Engl., Syllabus, ed. 2: 170. Mai 1898;

Lissocarpaceae Gilg in Engler et Gilg, Syllabus, ed.

9-10: 324. 6 Nov 1924, nom. cons.

Genera/species 2/550–600

Distribution Temperate to

tropical regions on both hemispheres, with their highest diversity in

Madagascar and Malesia; some species in temperate parts of eastern North

America, India, eastern China, and Japan.

Fossils Leaves, flowers and

fruits attributed to Ebenaceae

are known from the Eocene onwards, also from Europe. Austrodiospyros

cryptostoma is represented by male flowers and leaves from the Eocene of

southeastern Australia. Diospyros pollen have been found in Eocene

strata of North America.

Habit Usually dioecious

(rarely monoecious, polygamomonoecious or bisexual), usually evergreen (rarely

deciduous) trees or shrubs. Bark, roots and heartwood often black or, in air,

blackening.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

ab initio usually superficial (sometimes pericyclic). Primary medullary rays

narrow. Vessel elements usually with simple (rarely scalariform) perforation

plates; lateral pits alternate or opposite, bordered pits. Imperforate

tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids or libriform fibres with simple pits,

non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate. heterocellular. Axial

parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal scanty

vasicentric, reticulate, or banded. Wood elements often storied. Sieve tube

plastids S type. Nodes usually 1:1, unilacunar with one leaf trace (sometimes

1:3 or 3:3, unilacunar or trilacunar with three traces). Heartwood with

gum-like substances. Sclereids present. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals

frequent.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular,

simple or furcate, often malpighiaceous, with branches of unequal lengths, or

multicellular, uniseriate or stellate (in Lissocarpa absent);

glandular hairs, sometimes peltate-lepidote.

Leaves Usually alternate

(spiral or distichous; rarely opposite or verticillate), simple, entire,

coriaceous, with conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole

vascular bundle transection arcuate. Abaxial side of lamina usually with

flattened glands, extrafloral nectaries. Venation pinnate. Stomata usually

anomocytic (sometimes cyclocytic or actinocytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids

absent (in Lissocarpa?). Mesophyll often with sclerenchymatous

idioblasts containing brachysclereids, osteosclereids or other types of

sclereids. Extrafloral nectaries often present on abaxial side. Secretory

cavities absent. Leaf margin usually entire.

Inflorescence Axillary

fasciculate, raceme-like or paniculate cymose (flowers sometimes solitary,

terminal).

Flowers Actinomorphic. Pedicel

articulated. Usually hypogyny (in Lissocarpa epigyny). Sepals three to

five (to eight), with valvate or imbricate aestivation, persistent, connate.

Petals three to five (to eight), with contorted aestivation, connate (corolla

in Lissocarpa usually with eight-lobed corona). Nectariferous disc

usually absent.

Androecium Stamens (three to)

twelve to 20 (to c. 100), as many as or twice or four (or more) times the

number of petals, usually unequal in length, in two (to four) whorls. Filaments

flattened, free or connate two, three or more together (sometimes all filaments

connate into a tube), usually adnate at base to corolla tube. Anthers

basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, external anthers introrse,

mid-anthers latrorse and internal anthers extrorse, usually longicidal

(dehiscing by longitudinal slits; sometimes poricidal, with apical pores);

connective often slightly prolonged. Tapetum secretory, with multinucleate

cells. Female flowers usually with a single staminodial whorl.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tricolporate (rarely

tetracolporate; in Lissocarpa triporate), usually shed as monads

(rarely tetrads), bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with granular

infratectum (Diospyros), rugulate, microrugulate, striate, gemmate or

granulate (in Lissocarpa fossulate to rugulate).

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

two to eight connate carpels. Ovary usually superior (in Lissocarpa

inferior), usually bilocular to 16-locular; each locule usually divided by

secondary septa (ovary rarely unilocular; ovary in Lissocarpa

quadrilocular, not divided by secondary septa). Stylodia two to eight, free or

partially connate (style in Lissocarpa single, simple, clavate).

Stigmas capitate or bilobate (stigma in Lissocarpa often slightly

quadrilobate), non-papillate, Dry type. Male flowers usually with

pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation usually

apical (in Lissocarpa axile). Ovules one or two per carpel,

anatropous, pendulous, apotropous, bitegmic, tenuinucellar. Micropyle bistomal

or endostomal. Outer integument three to seven cell layers thick. Inner

integument five to ten cell layers thick. Megagametophyte monosporous,

Polygonum type. Endosperm development cellular (nuclear?). Endosperm

haustoria? Embryogenesis probably chenopodiad.

Fruit Usually a berry (rarely

capsule-like) with persistent and usually accrescent calyx. Pericarp with

tanniniferous idioblasts.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa

vascularized, with circumperipheral vascular loop surrounding seed. Tegmen?

Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, hard, oily, with mannose-rich

polysaccharides, sometimes ruminate. Embryo straight or curved, well

differentiated (Lissocarpa), without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two,

foliaceous. Radicula long. Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = 15, 30, 45 (or

more) – Polyploidy occurring.

DNA Mitochondrial

coxI intron present.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), cyanidin, C-30-oxidized triterpenes,

oleanolic acid derivatives, ellagic and gallic acids, methylated ellagic acids,

condensed tannins, proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins), saponins,

naphthoquinone derivatives of 7-methyljugone and plumbagin (droserone; bark and

wood blackening when substances oxidized, cf. ebony), anthraquinones, and

benzopyrones present. Alkaloids and cyanogenic compounds rare. Aluminium

accumulated in some species.

Use Ornamental plants, fruits,

timber, medicinal plants, fish poison.

Systematics Ebenaceae may be sister-group to the

clade [Maesa+[Samolus+Theophrastaceae]+ [Primulaceae+Myrsinaceae]] (Schönenberger &

al. 2005).

Ebenaceae and Sapotaceae have similar

malpighiaceous hairs (T-shaped with branches of unequal lengths).

Lissocarpa is sister to the remaining

Ebenaceae.

Lissocarpoideae (Gilg)

B. Walln. in Ann. Naturhist. Mus. Wien, Ser. B, 105: 523. 22 Apr 2004

1/8. Lissocarpa (8;

northwestern South America). – Vessel elements sometimes with scalariform

perforation plates. Hairs absent. Petiole sometimes with wing bundles and

recurved edges. Stomata anomocytic or cyclocytic. Inflorescence subfasciculate,

or flowers solitary axillary. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) large, apical.

Epigyny. Sepals four (or five). Petals four (or five). Corolla with an

eight-lobed corona. Stamens eight. Filaments connate. Connective prolonged.

Pollen grains triporate. Ovary in Lissocarpa quadrilocular, not

divided by secondary septa. Exine psilate. Pistil composed of four connate

carpels. Ovary quadrilocular, without secondary septa, inferior. Style single,

simple. Stigma clavate, often slightly quadrilobate, hairy at apex.

Placentation axile. Seeds one or two. Endosperm bony. Embryo well

differentiated. Cotyledons foliaceous. n = ? Iridoids, naphthoquinones etc.?

Ebenoideae (Juss.)

Thorne et Reveal in Bot. Rev. (Lancaster) 73: 121. 29 Jun 2007

1/550–600. Diospyros

(550–600; temperate to tropical regions on both hemispheres, with their

highest diversity in Madagascar and Malesia). – Phellogen usually superficial

(sometimes pericyclic). Cambium storied. Nodes sometimes 1:3, unilacunar with

three leaf traces. Silica bodies sometimes (‘Euclea’,

‘Royena’) present. Secretory cells abundant. Hairs usually

unicellular, sometimes T-shaped. Leaves usually distichous (sometimes spiral;

rarely opposite), with conduplicate ptyxis. Stomata usually paracytic.

Cuticular wax crystalloids absent. Inflorescence cymose, with short axis.

Floral buds acute, with depressed brown hairs. Sepals three to seven. Petals

three to seven, sometimes with valvate aestivation. Nectary absent. Stamens

(three to) twelve to 20 (to c. 100). Anthers extrorse, often hairy. Female

flowers usually with staminodia. Pollen grains usually tricolporate. Pistil

composed of two to eight connate antesepalous or antepetalous carpels. Ovary

locules usually divided by secondary septa. Stylodia two to eight, free or

partially connate. Stigmas capitate or lobate, little expanded, Dry type. Male

flowers with pistillodium. Placentation apical. Ovule often one per carpel,

bitegmic. Micropyle bistomal or endostomal. Endothelium present. Fruit often

with accrescent calyx. Seeds pachychalazal, often ruminate. Testa

multiplicative, usually vascularized, often parenchymatous. Exotesta often

fibriform or mucilaginous; exotestal cells cuboid to palisade. Endotesta often

crystalliferous; endotestal cell walls often thickened. Endosperm hard, with

thick cell walls. Radicula in the ‘Euclea’ and

‘Royena’ clades surrounded by ingrowth of seed coat. x = 15.

Flavonols (myricetin etc.), C-30-oxidized triterpenes, proanthocyanidins

(prodelphinidins), saponins, and naphthoquinone derivatives of 7-methyljugone

and plumbagin present. Ellagic acid not found. – Euclea (Africa) and

Royena (Africa) have sometimes been identified as the sister-group to

Diospyros

sensu stricto.

de Jussieu, Gen. Plant.: 159. 4 Aug 1789

[’Ericae’], nom. cons.

Kalmiaceae Durande,

Notions Elém. Bot.: 271. 1782 [’Kalmiae’], nom. illeg.;

Rhododendraceae Juss., Gen. Plant.: 158. 4 Aug 1789

[’Rhododendra’]; Rhodoraceae Vent.,

Tabl. Règne Vég. 2: 449. 5 Mai 1799; Ledaceae J. F.

Gmel., Allg. Gesch. Pflanzengifte, ed. 2: 404. Jun 1803 [’Leda’];

Epacridaceae R. Br., Prodr. Fl. Nov.-Holl.: 535. 27

Mar 1810 [’Epacrideae’], nom. cons.;

Azaleaceae Vest, Anleit. Stud. Bot.: 272, 294. 1818

[’Azaleoideae’]; Monotropaceae Nutt.,

Gen. N. Amer. Pl. 1: 272. 14 Jul 1818 [’Monotropeae’], nom. cons.;

Vacciniaceae DC. ex Perleb, Vers. Artzneikr. Pfl.:

228. Mai 1818 [’Vaccinieae’], nom.cons.;

Empetrales Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 251.

Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Empetreae’]; Epacridales

R. Br. ex Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 251. Jan-Apr 1820

[‘Epacrideae’]; Monotropales Bercht. et

J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 252. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Monotropeae’];

Empetraceae Hook. et Lindl. in W. J. Hooker, Fl.

Scot.: 297. 10 Mai 1821 [’Empetreae’], nom. cons.;

Pyrolaceae Lindl., Syn. Brit. Fl.: 175. 16 Mar 1829

[’Pyroleae’], nom. cons.; Empetrineae

Link, Handbuch 1: 617. 4-11 Jul 1829 [‘Empetreae‘];

Epacridineae Link, Handbuch 1: 601. 4-11 Jul 1829

[‘Epacrideae‘]; Ericineae Link, Handbuch

1: 601. 4-11 Jul 1829 [‘Ericeae genuinae‘];

Vacciniales Dumort., Anal. Fam. Plant.: 28. 1829

[‘Vaccinarieae’]; Stypheliaceae Horan.,

Prim. Lin. Syst. Nat.: 72. 2 Nov 1834 [’Stypheliaceae

(Epacrideae)’]; Arbutaceae (Meisn.) Miers

in Bromhead in Mag. Nat. Hist., n.s., 4: 337, 338. Jul 1840

[’Arbuteae’]; Andromedaceae Döll,

Rhein. Fl.: 428. 24-27 Mai 1843 [’Andromedeae’];

Arbutineae J. Presl in Nowočeská Bibl. [Wšobecný

Rostl.]: 987. 1846; Pyrolineae J. Presl in

Nowočeská Bibl. [Wšobecný Rostl.]: 987, 989. 1846

[‘Pyroleae‘]; Rhododendrineae J. Presl

in Nowočeská Bibl. [Wšobecný Rostl.]: 987, 996. 1846

[‘Rhododendreae‘]; Rhodorales Horan.,

Char. Ess. Fam.: 105. 30 Jun 1847 [‘Rhodorastra’];

Hypopityaceae Klotzsch in Linnaea 24: 11. Mai 1851

[’Hypopithieae’]; Menziesiaceae Klotzsch

in Linnaea 24: 11. Mai 1851; Siphonandraceae Klotzsch

in Linnaea 24: 11. Mai 1851, nom. illeg.;

Arctostaphylaceae J. Agardh, Theoria Syst. Plant.:

106. Apr-Sep 1858 [’Arctostaphyleae’];

Salaxidaceae J. Agardh, Theoria Syst. Plant.: 104.

Apr-Sep 1858 [’Salaxideae’];

Diplarchaceae Klotzsch in Monatsber. Königl. Preuss.

Akad. Wiss. Berlin 1859: 15. 1857 [’Diplarchaceen’], nom. illeg.;

Oxycoccaceae A. Kern., Pflanzenleben 2: 713, 714. 8

Aug 1891; Prionotaceae Hutch., Evol. Phylog. Fl. Pl.:

306. 28 Aug 1969

Genera/species c

117/3.900–3.950

Distribution Cosmopolitan,

although few species in tropical lowland regions, with their largest diversity

in the Himalayas to southwestern China, New Guinea, South Africa, Australia,

and New Zealand.

Fossils Seeds and fruits from

several genera with only extra-European recent distribution in the Northern

Hemisphere, e.g. Eubotrys, Leucothoe, Lyonia and

Zenobia, have been found in Late Cretaceous and Early Palaeogene

strata in Europe. Diplycosiopsis walbeckensis and Viticocarpum

minimum from the Maastrichtian of Germany is represented by drupes with

five many-seeded and one-seeded locules, respectively. It is, however,

uncertain whether they emanate from species of Ericaceae. Fossil leaves and pollen

grains from supposed Styphelioideae are known from (possibly the Late

Cretaceous to) the Early Palaeogene onwards in, above all, Australia.

Habit Usually bisexual (rarely

monoecious or dioecious), usually evergreen (sometimes deciduous) shrubs or

suffrutices (rarely trees, lianas or perennial herbs). Some genera consist of

achlorophyllous and mycotrophic plants. Numerous species are xerophytic. Some

species are helophytes. A starchy lignotuber is present especially in many

species in mediterranean climates.

Vegetative anatomy

Ectomycorrhiza usually with Basidiomycotina (i.a.

Sebacinales) or often with certain Ascomycotina (particularly

Pezizales, e.g. Hymenoscyphus) as intracellular hyphal

complexes in root epidermis (monotropoid, ericoid or arbutoid mycorrhiza);

ericoid mycorrhiza penetrates only epidermal and outer cortical cells of hair

roots (consisting of endodermis, exodermis, tracheids, sieve tubes and

companion cell) covered with hyphae (Hartig net and fungal mantle not formed);

arbutoid mycorrhiza penetrates epidermal and outer cortical cells of hair

roots, these being covered by Hartig net with hyphae following cell walls or

forming complete envelope (Hartig net and fungal mantle formed); in monotropoid

mycorrhiza root covered in the same way, although hyphae form peg-shaped

invaginations into exodermal hair root cells (Hartig net and fungal mantle

formed); arbuscular mycorrhiza present in Enkianthus; standard

ectomycorrhiza not known in Ericaceae. Endophytic fungi

frequently present. Phellogen ab initio usually pericyclic (sometimes

superficial; absent in Monotropoideae). Pericyclic fibres little

developed. Secondary lateral growth usually normal (absent in most

Monotropoideae). Vessel elements usually with simple or scalariform

(rarely reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform, opposite or

alternate (vessels absent in most Monotropoideae), simple and/or

bordered pits. Vestured pits sometimes present. Imperforate tracheary xylem

elements tracheids or fibre tracheids or libriform fibres with simple and/or

bordered pits, usually non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays

uniseriate or multiseriate, usually heterocellular. Axial parenchyma

apotracheal diffuse (rarely diffuse-in-aggregates), or paratracheal scanty

vasicentric or unilateral, or absent. Sieve tube plastids usually S type

(sometimes S0 type). Endodermis rarely with suberised cell walls.

Nodes usually 1:1, unilacunar with one leaf trace (rarely ≥3:≥3, trilacunar

or multilacunar with three or more traces). Cortex with sclereids. Raphid cells

absent. Calciumoxalate druses or single prismatic crystals often frequent.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or

multicellular, uniseriate or branched, dendritic, stellate, lepidote,

bristle-like, sometimes candelabra-, funnel- or cup-shaped; glandular hairs

present (sometimes peltate-lepidote), often thick and colleter-like.

Leaves Alternate (sometimes

distichous or tetrastichous), opposite or verticillate, simple, entire, usually

coriaceous, often ericoid (in Monotropoideae usually scale-like), with

convolute, involute or revolute ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent.

Colleter-like thick glandular hairs often present on adaxial side of petiole

base. Petiole vascular bundle transection usually arcuate (sometimes annular).

Extrafloral nectaries sometimes present on petiole or base of lamina. Venation

usually pinnate (rarely palmate or parallelodromous) or leaves one-veined.

Stomata usually anomocytic or paracytic (rarely parallelocytic, cyclocytic or

stephanocytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids usually amorphous or as platelets

(sometimes as tubuli, dominated by β-diketones, or as coiled or triangular

rodlets). Epidermis with or without mucilage cells. Secretory oil cavities

present or absent. Leaf margin serrate, crenate or entire; teeth united via

multicellular hairs.

Inflorescence Terminal or

axillary, racemes, spikes, panicles or fascicles (sometimes umbels, rarely

heads or flowers solitary).

Flowers Actinomorphic or

zygomorphic. Hypogyny to epigyny. Sepals (two to) four or five (to seven), with

imbricate quincuncial aestivation, persistent, usually connate at base. Petals

(three or) four or five (to seven), with valvate or imbricate (rarely

contorted) aestivation, persistent or caducous, usually connate into

campanulate, tubular or urceolate corolla (rarely free; in Richea

connate into calyptra). Nectary or nectariferous disc (annular or of separate

parts, intrastaminal) usually at base (sometimes at apex) of ovary (sometimes

absent).

Androecium Stamens usually

four or five (rarely two or three), antesepalous, alternipetalous, or 4+4,

5+5(–16), usually obdiplostemonous. Filament usually free from each other and

from tepals (in, e.g., Styphelioideae often epipetalous). Anthers

basifixed or dorsifixed, late inverted, finally resupinate (in

Enkianthoideae, Monotropoideae and Arbutoideae

sometimes not inverted), often versatile, usually free (rarely connate), often

with two (rarely four) small usually apical horn-shaped outgrowths (sometimes

dorsal spurs; in Vaccinioideae sometimes tubular outgrowths), usually

tetrasporangiate (in Styphelioideae disporangiate), subintrorse and

poricidal (dehiscing by apical pores), or introrse (rarely latrorse or

extrorse) and longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits; in

Styphelioideae usually with a single slit). Tapetum secretory, with

uni-, bi- or multinucleate cells. Staminodia absent. Secondary pollen display

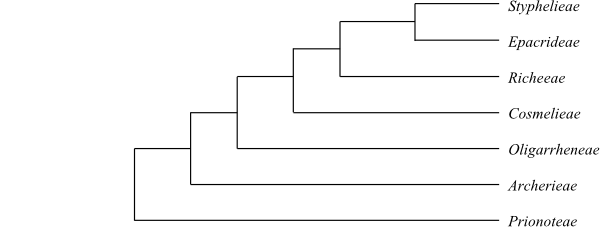

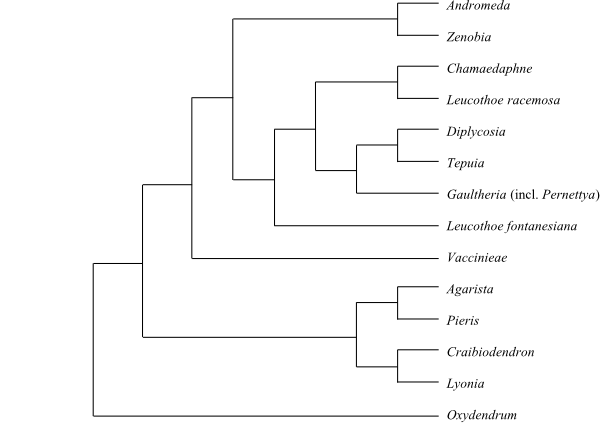

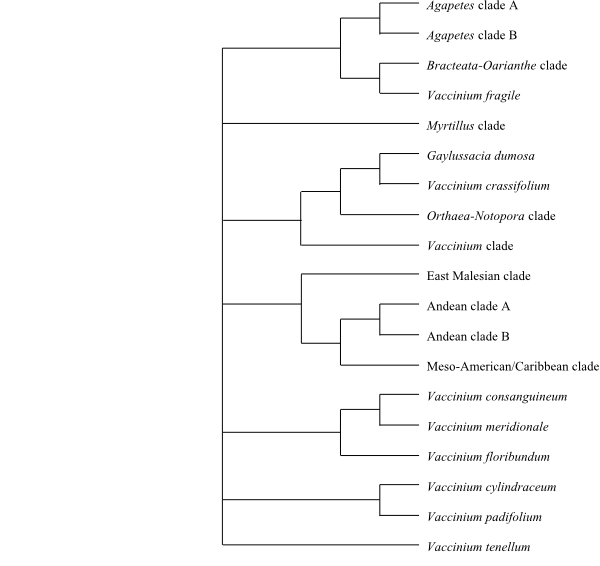

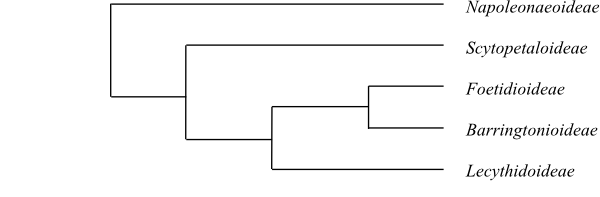

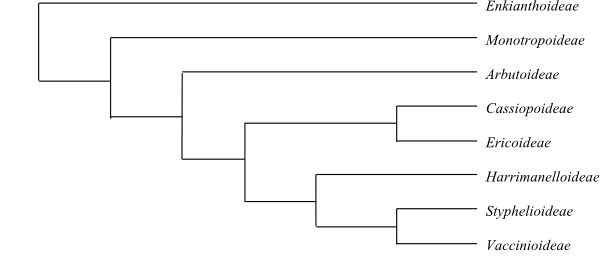

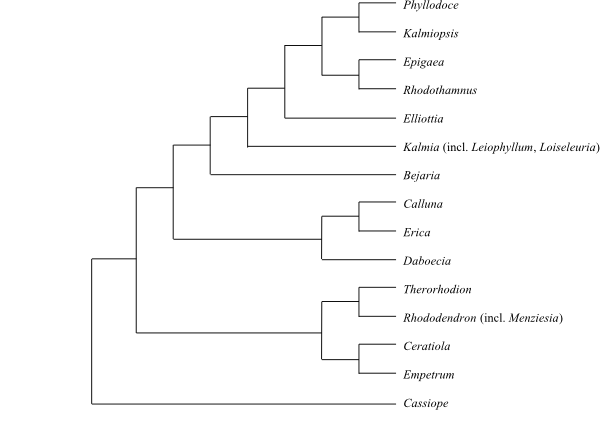

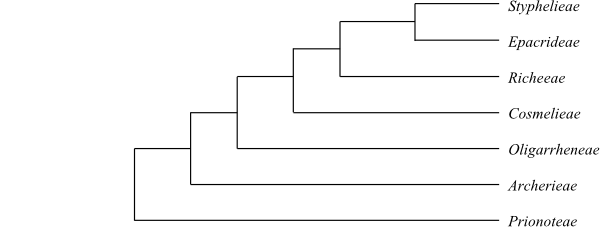

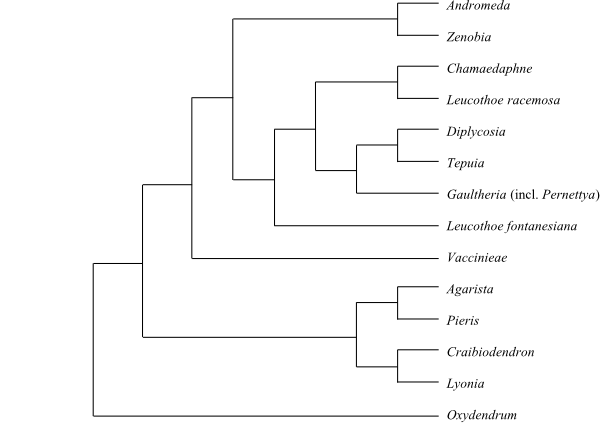

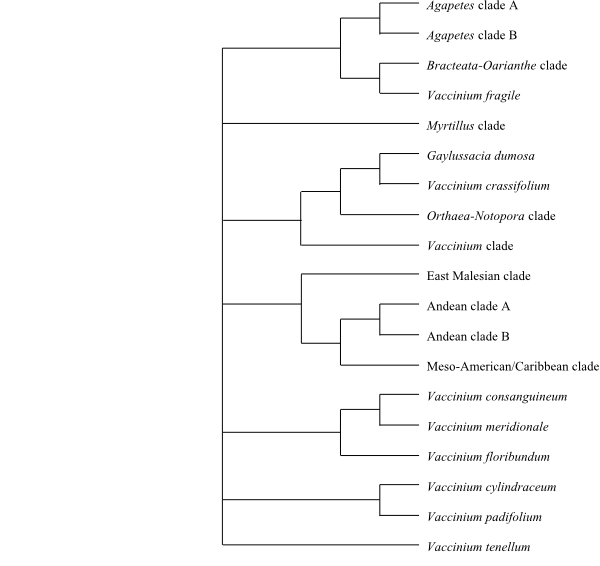

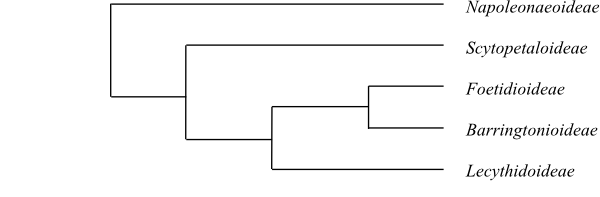

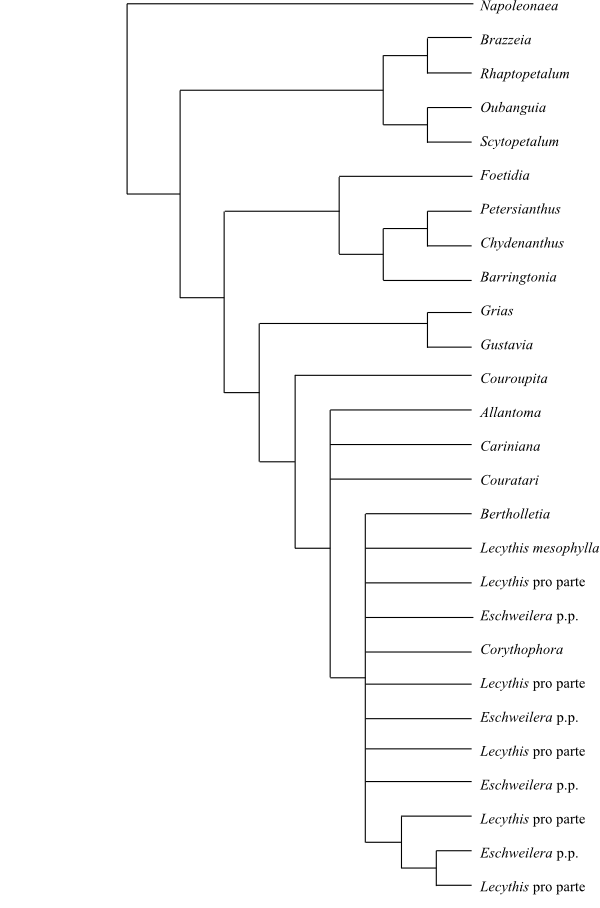

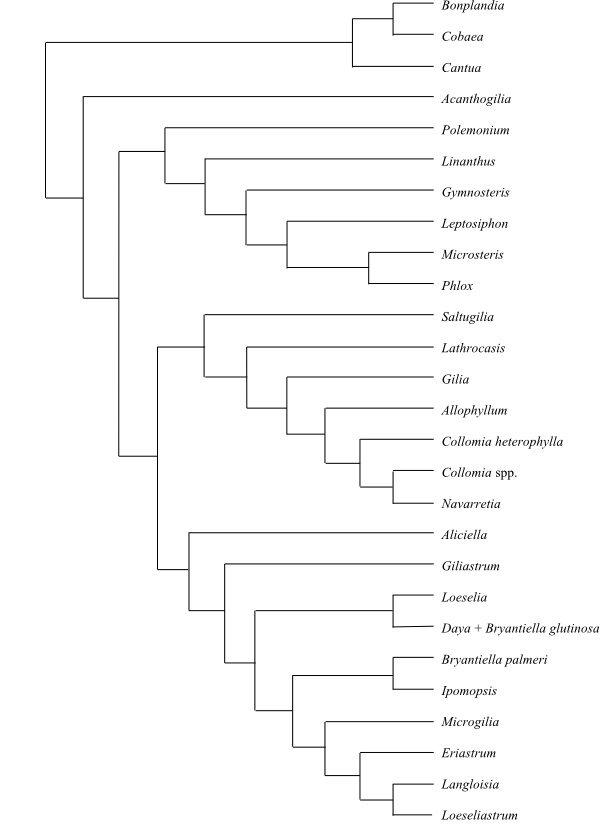

present in Styphelioideae.