SUPERROSIDAE W. S. Judd, D. E.

Soltis et P. S. Soltis

Judd, Soltis et Soltis in Amer. J. Bot. 98:

E21-E22. Apr 2011

[Saxifragales+Rosidae]

SAXIFRAGALES Bercht. et J.

Presl

Berchtold et Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 259. Jan-Apr

1820 [‘Saxifrageae’]

Hamamelidanae Takht.,

Sist. Filog. Cvetk. Rast. [Syst. Phylog. Magnolioph.]: 113. 4 Feb 1967;

Hamamelididae Takht., Sist. Filog. Cvetk. Rast.

[Syst. Phylog. Magnolioph.]: 461. 4 Feb 1967, pro parte;

Saxifraganae Reveal in Phytologia 76: 4. 2 Mai

1994

Fossils Archamamelis

bivalvis is represented by fossil flowers from the Late Santonian to the

Early Campanian of Sweden. The hexamerous or heptamerous flowers have a

bicyclic perianth, one series of stamens, one whorl of staminodia, and a

gynoecium of three connate carpels. Divisestylus from the Turonian of

New Jersey comprises fossil pentamerous flowers with alternipetalous stamens

containing striate pollen, an intrastaminal nectariferous disc and two carpels

connate at stigmatic and ovary regions; the capsules were apically dehisced and

the stomata anomocytic. The Coniacian Lindacarpa pubescens from

eastern Siberia is a spherical female inflorescence, the flowers of which

having connate sepals and a semi-inferior gynoecium of two connate carpels.

Microaltingia apocarpela, from the Turonian of New Jersey, consists of

stalked spherical female inflorescences with two basally connate semi-inferior

ovaries per flower.

Habit Bisexual, monoecious,

andromonoecious, polygamomonoecious, dioecious, androdioecious or

polygamodioecious, evergreen or deciduous trees, shrubs or suffrutices (rarely

lianas), perennial, biennial or annual herbs. Many representatives are

succulent and/or xerophytic with CAM-physiology. Sometimes aquatic.

Vegetative anatomy Roots often

diarch. Phellogen ab initio subepidermal, pericyclic or outer-cortical.

Secondary lateral growth normal or absent. Tension wood sometimes present.

Vessel elements usually with scalariform (sometimes simple, rarely reticulate)

perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform, opposite or alternate (rarely

reticulate), simple or bordered pits, non-septate. Vestured pits sometimes

present. Imperforate tracheary elements fibre tracheids or libriform fibres

(sometimes tracheids) with simple or bordered pits, usually non-septate, or

absent (sometimes also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate or

multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular, or absent. Axial parenchyma

apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal scanty,

vasicentric, unilateral or banded, or absent. Sieve tube plastids Ss or

S0 type. Nodes usually 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces

(sometimes 1:1–3 or ≥5:≥5, unilacunar or multilacunar with one or several

traces). Cystoliths sometimes numerous. Secretory cells sometimes with

proanthocyanidins and/or ellagitannins. Idioblasts with cyanogenic compounds or

druses unusual. Schizolysigenous resinous canals with balsam sometimes

abundant. Tanniniferous cells sometimes frequent. Prismatic calciumoxalate

crystals, druses or crystal sand often present (rarely elongate crystals or

styloids).

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or

multicellular, uniseriate or multiseriate, often branched (furcate, stellate,

sometimes rarely arachnoid), stalked or unstalked, or absent (sometimes tufted,

peltate, clavate or vesicular; often with multicellular apical gland);

glandular hairs sometimes frequent, sometimes peltate or lepidote; prickles

sometimes abundant on branch epidermis.

Leaves Usually alternate

(spiral or distichous; sometimes opposite or verticillate), simple or pinnately

or palmately compound, entire or lobed, with usually conduplicate or involute

(sometimes flat or curved, rarely plicate, supervolute or convolute) ptyxis

(leaves sometimes succulent). Stipules usually absent (sometimes intrapetiolar,

rarely pairwise); leaf base usually absent (sometimes sheathing). Colleters

sometimes present. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate or annular,

sometimes with medullary or adaxial bundles. Venation pinnate or palmate,

actinodromous, eucamptodromous, brochidodromous or craspedodromous; lateral

veins often running out into (glandular) leaf teeth. Stomata usually anomocytic

or paracytic (sometimes anisocytic or diacytic, rarely helicocytic), often only

on adaxial side of lamina. Cuticular wax crystalloids usually as tubuli (often

clustered tubuli [Berberis type, at least in some woody Saxifragales], sometimes as

rodlets, threads or platelets), chemically often dominated by nonacosan-10-ol.

Domatia as pockets or hair tufts, or absent. Mesophyll and petiolar cortex

sometimes with calciumoxalate as druses or single prismatic crystals. Leaf

margin usually serrate (sometimes entire, crenate or biserrate); leaf teeth

usually rosoid, sometimes platanoid (glandular with cavity, lateral veins

almost reaching teeth), fothergilloid (with transparent glandular apex, lateral

veins almost reaching teeth) or chloranthoid (with persistent transparent

swollen structure, into which high order lateral veins proceed).

Inflorescence Terminal or

axillary, racemes, spikes or heads, or raceme-, spike- or head-like, pleio-,

di- or monochasia, thyrsoids, fasciculate, panicles, corymbs, racemes or

cincinnate (flowers rarely solitary). Floral prophylls (bracteoles) sometimes

absent.

Flowers Usually actinomorphic

(rarely zygomorphic). Hypanthium sometimes present. Epigyny or half epigyny

(sometimes hypogyny). Sepals (two to) four or five (sometimes eight or ten),

with imbricate or valvate aestivation, free (sometimes connate at base;

sometimes spiral or absent). Petals (two to) four or five (to 13), with

imbricate or valvate aestivation, free (sometimes spiral or absent). Nectary

and disc absent, or nectariferous disc intrastaminal.

Androecium Stamens (one to)

four or five (to more than 100), usually whorled, alternisepalous, or

(4–)5+(4–)5, diplostemonous or obdiplostemonous (sometimes spiral).

Filaments usually free (rarely connate at base, usually free from tepals

(rarely epipetalous). Anthers usually basifixed (usually with filament attached

at basal pit; rarely dorsifixed), usually non-versatile, usually

tetrasporangiate (rarely disporangiate), usually latrorse (sometimes introrse

or extrorse), usually longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits; rarely

valvate or with a basal pore or short apical slits). Tapetum secretory.

Staminodia usually absent (sometimes antepetalous; female flowers sometimes

with staminodia).

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains 2–3-colpate,

2–3-colpor(oid)ate or polypantoporate (sometimes diporate, rately triporate),

shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate, with

usually columellate (rarely granular) infratectum, perforate, reticulate,

rugulate or striate, verrucate, echinulate, spinulate, scabrate or psilate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

one to 32, usually connate (sometimes free, at least in distal part) carpels,

sometimes unsealed distally-ventrally (sometimes spiral); carpel plicate. Ovary

inferior or semi-inferior (sometimes superior), unilocular (apocarpy) to

quadrilocular. Stylodia two to numerous, free, or absent. Stigmas usually

capitate (sometimes decurrent), papillate, Dry or Wet type. Pistillodium

usually absent (male flowers sometimes with pistillodium/pistillodia).

Ovules Placentation axile or

parietal (sometimes apical or marginal to laminar). Ovules one to more than 100

per carpel, anatropous (sometimes hemianatropous), pendulous, horizontal or

ascending, apotropous or epitropous, usually bitegmic (rarely unitegmic),

usually crassinucellar (sometimes tenuinucellar). Micropyle usually bistomal,

often Z-shaped (zig-zag; rarely exostomal). Nucellar cap sometimes present.

Megagametophyte usually monosporous, Polygonum type (rarely disporous,

Allium type). Synergids often with a filiform apparatus, rarely

haustorial. Endosperm development usually cellular (rarely helobial or

nuclear). Endosperm haustorium chalazal or absent. Embryogenesis solanad,

caryophyllad or chenopodiad.

Fruit Usually a follicle, a

septicidal and/or loculicidal capsule or a nut (sometimes a drupe, a berry, or

an assemblage of follicles or nutlets, or a syncarp consisting of follicles or

septicidal capsules, rarely a schizocarp with nut-like mericarps).

Seeds Aril usually absent

(sometimes funicular aril enclosing seed entirely or partially). Seed coat

testal or exotestal (sometimes mesotestal or endotegmic). Exotestal cells often

with outer wall (sometimes radial walls) thickened (sometimes partially

crushed). Inner pigmented layer often present. Tegmen usually crushed (inner

exotegmic layer sometimes pigmented). Endotegmen sometimes with thick

sclerotic, cutinized, tanniniferous and/or crystalliferous cell walls.

Perisperm usually not developed (sometimes more or less developed). Endosperm

copious or sparse, oily, proteinaceous (rarely starchy). Embryo large or small,

straight or curved, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two. Germination

phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 5–37

DNA Insertion present in 18S

rDNA. I copy of nuclear gene RPB2 lost. Mitochondrial intron

coxII.i3 sometimes lost.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin, apigenin, luteolin, etc.), afzelechin (a

flavan-3-ol), methylated and non-methylated flavones, acylated flavonol

glycosides, pelargonidin, chalcones, dihydrochalcones, cyanidin, delphinidin,

mono- and sesquiterpenes, oleanolic acid derivatives, toxic bufadienolides,

Group I carbocyclic iridoids (e.g. daphylloside, monotropein, asperuloside,

daphniphylloside), ellagic and gallic acids, bergeniin (C-glycoside of

gallic acid), ellagic or gallic acid based hydrolyzable tannins (tellimagrandin

I and II etc.), condensed tannins (from procyanidin or prodelphinidin),

proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins), myriophyllin, pyridine alkaloids,

glycosides (e.g. paeonol, paeonolide, paeonoside, paeoniflorin,

oxypaeoniflorin, benzoylpaeoniflorin and alliflorin), isoleucine-, tyrosine- or

valine-derived cyanogenic compounds, coumaric acid, arbutin, acetophenones,

galloylic esters, and germacrane-like compounds present. Squalene alkaloids of

the daphniphyllin group rare. Saponins not found.

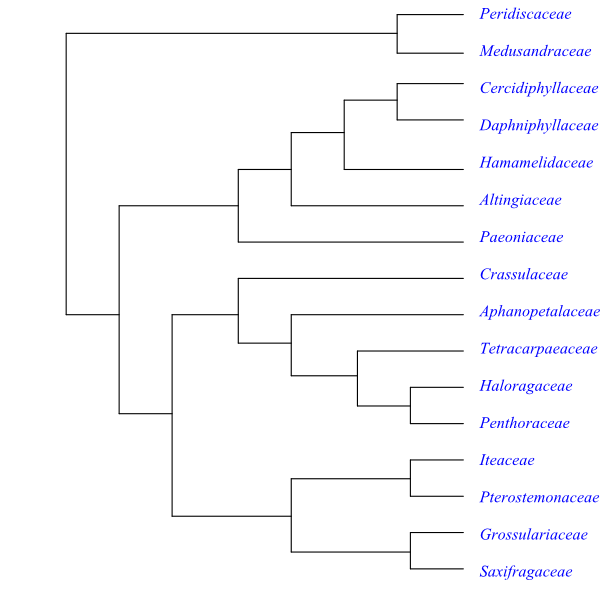

Systematics Saxifragales are sister to

Rosidae.

[Peridiscaceae+Medusandra]

are sister-group to the remaining Saxifragales.

The remaining Saxifragales have the

following more or less strongly supported topology: [[Paeoniaceae+[Altingiaceae+[Hamamelidaceae+[Cercidiphyllaceae+Daphniphyllaceae]]]]+

[[Crassulaceae+[Aphanopetalaceae+[Tetracarpaeaceae+[Haloragaceae+Penthoraceae]]]]+ [[Iteaceae+Pterostemonaceae]+[Grossulariaceae+Saxifragaceae]]]]. It is

supported by the potential synapomorphies (Stevens 2001 onwards): floral apex

flat to concave early in development; and ovary often inferior to

semi-inferior.

The first main clade, with the topology [Paeoniaceae+[Altingiaceae+[Hamamelidaceae+ [Cercidiphyllaceae+Daphniphyllaceae]]]], has

the synapomorphies leaves with basically palmate venation; and absence of

mitochondral intron coxII.i3. The clade [Altingiaceae+ [Hamamelidaceae+[Cercidiphyllaceae+Daphniphyllaceae]]] is

characterized by cuticular wax crystalloids as tubuli, dominated by

nonacosan-10-ol; usually racemose inflorescence; absence of pedicel; valvicidal

anther with apically protruding connective; and an elongate embryo. Cercidiphyllaceae and

Daphniphyllaceae

share the potential synapomorphies dioecy; small flowers; absence of petals;

and hypogyny.

The second main clade [[Crassulaceae+[Aphanopetalaceae+[Tetracarpaeaceae+[Haloragaceae+Penthoraceae]]]]+[[Iteaceae+Pterostemonaceae]+[Grossulariaceae+Saxifragaceae]]] has the

following potential synapomorphies, according to Stevens (2001 onwards):

superficial phellogen; vessel elements with simple perforation plates; petiole

bundle transection arcuate; cuticular wax crystalloids not as tubuli; ovules

apotropous; and calyx persisting as withered. The clade [Crassulaceae+[Aphanopetalaceae+[Tetracarpaeaceae+[Haloragaceae+Penthoraceae]]]] has the

synapomorphies: endodermis usually present in stem; nodes 1:1; absence of

stipules; and tricolporate pollen grains. The [[Iteaceae+Pterostemonaceae]+[Grossulariaceae+Saxifragaceae]] clade has

spiral leaves; presence of hypanthium; antesepalous stamens as many as sepals;

ovules numerous per carpel; and a septicidal capsule. Iteaceae and Pterostemonaceae share the

features: presence of stipules; one style; axile placentation; sparse

endosperm; and presence of flavone-C-glycosides. Likewise, Grossulariaceae and Saxifragaceae share the

characters two or three connate carpels; and sometimes helobial endosperm

development.

|

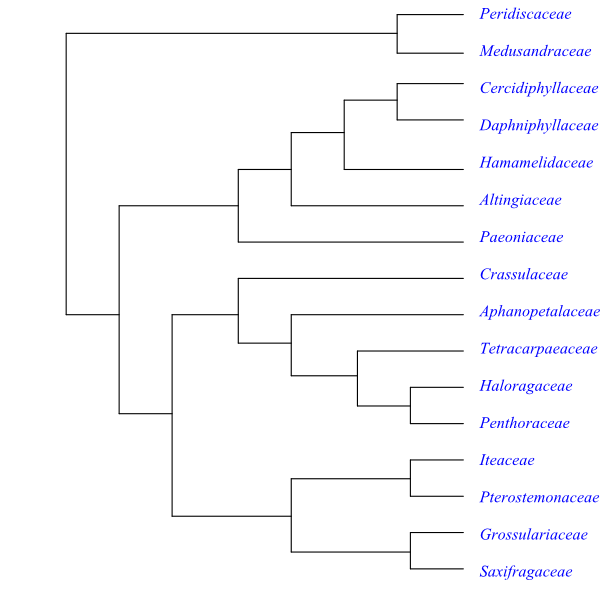

Bayesian consensus tree of Saxifragales based on

DNA sequence data (Jian & al. 2008). [Peridiscaceae+Medusandra]

are sister group to the remaining Saxifragales with a

high bootstrap support. The bootstrap support for Paeonia

being sister to the woody Saxifragales was only

59% in analyses by Soltis & al. (2011), whereas the remaining

clades are very strongly supported. Paeoniaceae were recovered

as sister to the herbaceous groups

Crassulaceae–Saxifragaceae by Dong & al. (2018). There

is significant support for placing Cynomorium

(Cynomoriaceae) either within Saxifragales or as

sister to this clade (Su & al. 2015).

|

Horaninov, Osnov. Bot.: 271. 1841, nom. cons.

Altingiales Doweld,

Ann. Bot. (London) 82: 435. Oct 1998

Genera/species 1/13–15

Distribution Eastern

Mediterranean to eastern Himalayas, India, China, Taiwan, Indochina, West

Malesia, eastern and northeastern North America, Mexico, Central America.

Fossils Altingiaceae are richly

represented by Cenozoic fossils, particularly from the Miocene and the

Pliocene. Infructescences of Steinhauera from Eocene layers in Europe

resemble those in Liquidambar.

Habit Monoecious, usually

deciduous (sometimes evergreen) trees.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

ab initio superficial. Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates;

lateral pits scalariform or opposite, simple pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem

elements ? with bordered pits, non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate or

multiseriate, homocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse, or

paratracheal scanty, or absent. Sieve tube plastids Ss type. Nodes trilacunar?

Schizolysigenous resinous canals with balsam abundant in most tissues.

Calciumoxalate crystals?

Trichomes Hairs multicellular,

uniseriate or stellate, or absent.

Leaves Alternate (spiral),

simple, usually palmately lobed (rarely entire), with flat-conduplicate ptyxis.

Stipules (intra?)petiolar, small, usually caducous; leaf sheath absent. Petiole

vascular bundle transection annular; petiole with medullary bundles. Venation

palmate, usually actinodromous (sometimes camptodromous). Stomata paracytic.

Cuticular wax crystalloids as tubuli? Domatia as pockets or hair tufts. Leaf

margin usually serrate (rarely entire); leaf teeth platanoid (glandular with

cavity).

Inflorescence Terminal, cymose

(condensed panicles); male inflorescences capitula in spike- or raceme-like

partial inflorescences; female inflorescences globular, with intercarpellary

outgrowths corresponding to sterile flowers.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small.

Epigyny? Tepals absent (or as tiny rudimentary scales?). Nectary absent. Disc

absent.

Androecium Stamens four to

ten. Filaments free. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate,

latrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal valves or slits). Tapetum

secretory. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains triporate to polypantoporate,

shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine semitectate, with columellate

infratectum, finely reticulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

two connate carpels; carpels with various orientation (sometimes transversely

orientated), unsealed, only lower carpels fertile. Ovary inferior?, bilocular.

Style absent. Stigmas much decurrent, with multicellular appendages (sometimes

unicellular papillae?), Dry type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation axile.

Ovules c. 20 to 47 (only lower ovules fertile) per carpel, anatropous?,

horizontal, apotropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle usually bistomal?

(sometimes endostomal). Outer integument approx. two cell layers thick. Inner

integument approx. five cell layers thick. Megagametophyte monosporous,

Polygonum type. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm

haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit Septicidal (and

occasionally loculicidal) lignified capsules (sometimes more or less connate).

Endocarp cells thickened, transversely elongate relative to longitudinal axis

of fruit.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed winged

(wings developed from elongation of integuments surrounding micropyle). Seed

coat testal (or exotegmic?). Exotestal cell walls often lignified. Mesotestal

cells more or less sclerotized. Endotestal cells oblong, with lignified walls.

Exotegmen well developed? Endotegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm poorly

developed. Embryo long, straight, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two, flattened.

Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 15, 16 –

Polyploidy occurring.

DNA Mitochondrial intron

coxII.i3 lost.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(quercetin, myricetin), cyanidin, Group I carbocyclic iridoids (daphylloside,

monotropein), ellagic acid, tannins, and proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins)

present. Cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Ornamental plants, timber,

carpentry, medicinal plants (gum from Liquidambar orientalis).

Systematics Liquidambar

(13–15; eastern Mediterranean [the Aegean Islands, Rhodos, Cyprus, southern

Turkey], India, Assam, the Himalayas, China, Taiwan, Indochina, West Malesia,

Taiwan, southeastern Canada, eastern United States, eastern and southern Mexico

to Costa Rica).

A basal branching of Liquidambar

comprises one East Asiatic clade and one European-American clade (Ickert-Bond

& Wen 2006).

The Cretaceous fossils Lindacarpa,

Microaltingia and Vilyungia do not belong in Altingiaceae, according to

Friis & al. (2011). They are instead considered “unassigned Saxifragales”.

Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.: xxvii. 23 Dec

2001

Genera/species 1/2

Distribution Western and

southeastern Australia.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, evergreen

climbing shrub or liana. Lenticels elevated and prominent.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

ab initio superficial. Endodermis distinctly delimited, as innermost cortical

layer. Pericyclic fibres absent. Vessel elements with scalariform perforation

plates; lateral pits?, bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements

fibre tracheids with bordered pits?, non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate

homocellular or multiseriate heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal

diffuse, or paratracheal scanty. Ray parenchyma cells starchy. Sieve tube

plastids Ss type? Nodes 1:1(–2), unilacunar with one bifid leaf trace.

Crystals?

Trichomes Hairs absent.

Leaves Usually opposite

(rarely verticillate), simple, entire, with ? ptyxis. Stipules? present on both

sides of nodes, modified into tooth-like colleters; leaf sheath absent. Petiole

bundle transection arcuate?; petiole with usually three (rarely one) vascular

bundles. Venation pinnate. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular waxes? Leaf margin

entire or serrate; leaf teeth one-veined, salicoid, without glands.

Inflorescence Axillary,

paniculate cymose, or flowers solitary.

Flowers Actinomorphic.

Hypanthium present, short. Half epigyny. Sepals four (or five), with imbricate

aestivation, persistent, largely free. Petals four (or five), rudimentary and

visible only as young, free, or absent. Tepals connate at base into tube.

Nectary? Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens usually

eight (sometimes ten). Filaments connate at base into a tube, adnate to tetals

(epitepalous). Anthers elongate, almost basifixed, non-versatile,

tetrasporangiate, latrorse-introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal

slits); connective prolonged. Tapetum secretory? Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous? Pollen grains tricolporate, shed as monads,

bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate? infratectum,

rugulate-stellate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

four connate antepetalous carpels. Ovary semi-inferior, quadrilocular. Style

single, quadrilobate, with four stylar canals. Stigma papillate, type?

Pistillodium?

Ovules Placentation

apical-axile. Ovule usually one (rarely two) per carpel, anatropous, pendulous,

epitropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Funicle long, thick. Micropyle bistomal.

Outer integument ? cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick.

Parietal tissue? Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type.

Endosperm development? Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A one-seeded nut with

persistent and accrescent calyx.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed

reniform or hippocrepomorphic, often winged or with long hairs. Testa? Tegmen?

Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious?, fleshy. Embryo curved,

chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Germination?

Cytology n = ?

DNA

Phytochemistry Unknown.

Use Ornamental plants

(Aphanopetalum resinosum).

Systematics

Aphanopetalum (2; A. clematideum: westernmost Western

Australia; A. resinosum: warm-temperate parts of southern Queensland

and New South Wales).

Aphanopetalum is sister to the clade

[Tetracarpaeaceae+[Haloragaceae+Penthoraceae]].

Engler, Syllabus, ed. 5: 126. Jul 1907, nom.

cons.

Cercidiphyllales Hu

ex Reveal in Phytologia 74: 174. 25 Mar 1993

Genera/species 1/1–2

Distribution: China, Japan.

Fossils Reports of Cercidiphyllaceae from

the Cretaceous, based on leaves and fruits, are ambiguous. On the other hand,

the Paleocene Joffrea speirsiae from Alberta (Canada) has an elongated

receptacle and a bicarpellate pistil with the adaxial sutures directed against

one another, resembling extant Cercidiphyllaceae.

Similar fossils are known from the Maastrichtian of western North America.

Fossilized leaves and inflorescences (with flowers possessing sometimes

pentamerous perianth) indicate that Cercidiphyllum was widely

distributed in the Northern Hemisphere during the Cenozoic.

Habit Usually dioecious

(rarely monoecious), deciduous trees with very distinct difference between long

and short shoots.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

ab initio outer-cortical. Primary medullary rays narrow. Primary stem with

continuous vascular cylinder. Vessel elements with scalariform perforation

plates; lateral pits opposite to scalariform, simple and/or bordered pits.

Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids with bordered pits,

non-septate. Wood rays biseriate with uniseriate ends, heterocellular. Axial

parenchyma apotracheal diffuse?, or paratracheal scanty or banded, or absent.

Tyloses abundant. Sieve tube plastids Ss type. Nodes on short shoots unilacunar

(with one leaf trace?), on long shoots trilacunar (with three traces?).

Parenchyma with prismatic calciumoxalate crystals.

Trichomes Hairs usually

absent.

Leaves Usually opposite

(rarely verticillate) on long shoots, a few alternate on short shoots, simple,

entire, with involute ptyxis. Stipules adaxial-petiolar (intrapetiolar), small,

caducous; leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundles? Leaf bases on long

shoots cuneate, on short shoots cordate. Venation palmate brochidodromous.

Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids as clustered tubuli

(Berberis type), chemically dominated by nonacosan-10-ol. Mesophyll

and petiolar cortex with calciumoxalate as druses or single prismatic crystals.

Leaf margin on long shoots entire to finely serrate, on short shoots crenate;

leaf teeth chloranthoid (with persistent transparent swollen structure, into

which higher order lateral veins proceed).

Inflorescence Terminal, dense,

few-flowered on sympodial short shoots; female inflorescences capitate

pseudanthia, with two to eight flowers, often surrounded by involucre of

sepaloid bracts; male inflorescences raceme-like, short, with (lower flowers)

or without (upper flowers) bracts. Prophyll adaxial.

Flowers At least male flowers

zygomorphic (with stamens on abaxial side). Hypogyny? Tepals absent. Nectary

absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens 16–35, in

fascicles (flowers?) each with one to 13 stamens. Each staminal fascicle

(flower?) subtended by a single bract. Filaments long, thin, free. Anthers

basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, latrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by

longitudinal slits); connective somewhat prolonged at apex. Tapetum secretory,

with binucleate cells. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains tricolpate, shed as monads,

bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum, perforate

or finely reticulate, beset with supratectal verrucae.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

one carpel (monocarpellate); carpel plicate, somewhat stipitate, with abaxial

ventral suture. Ovary superior?, unilocular (apocarpy). Stylodium long. Stigma

decurrent its entire length, papillate, Dry type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation

laminal-lateral (marginal). Ovules c. 15 to c. 30 per carpel, anatropous,

pendulous, apotropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle bistomal. Outer

integument four or five cell layers thick. Inner integument two or three cell

layers thick. Chalazal end elongating into a wing-like structure during

maturation. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm

development ab initio cellular. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis

caryophyllad.

Fruit A follicle. Groups of

adjacent follicles forming a syncarp (multifolliculus).

Seeds Aril absent. Seed small,

with a chalazal wing-like appendage with hairpin-like vascular bundle. Seed

coat testal. Testa indistinct. Exotestal cells enlarged, somewhat thickened.

Tegmen tanniniferous, degenerating. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm poorly

developed, oily, with one large suspensor cell. Embryo large, straight, well

differentiated, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two. Germination

phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 19

DNA Mitochondrial intron

coxII.i3 lost.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin), cyanidin, chalcones, dihydrochalcones, ellagic acid,

and tannins present. Cyanogenic compounds and saponins not found.

Use Ornamental plants,

carpentry.

Saint-Hilaire, Expos. Fam. Nat. 2: 123. Feb-Apr

1805 [‘Crassuleae’], nom. cons.

Sempervivaceae Juss.,

Gen. Plant.: 207. 4 Aug 1789 [‘Sempervivae’];

Sedaceae Roussel, Fl. Calvados, ed. 2: 291. 1806

[’Sedoideae’]; Cotyledonaceae Martinov,

Tekhno-Bot. Slovar: 168. 3 Aug 1820 [‘Cotyledones’];

Rhodiolaceae Martinov, Tekhno-Bot. Slovar: 546. 3 Aug

1820 [‘Rhodioleae’]; Sempervivales Juss.

ex Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 238. Jan-Apr 1820

[‘Semperviveae’]; Tillaeaceae Martinov,

Tekhno-Bot. Slovar: 635. 3 Aug 1820; Sedales Reichb.,

Bot. Damen: 462. 1828 [’Sediflorae’];

Crassulales Link, Handbuch 2: 18. 4-11 Jul 1829

[’Crassulaceae’];

Sedineae Rchb., Deutsch. Bot. Herb.-Buch: lxiii. Jul

1841 [‘Sediflorae’]; Crassulopsida

Brongn., Enum. Plant. Mus. Paris: xxviii, 106. 12 Aug 1843

[’Crassulineae’]

Genera/species

30?/1.270–1.325

Distribution Temperate,

subtropical and alpine regions on both hemispheres, with their largest

diversity in Mexico and southern Africa.

Fossils Uncertain.

Habit Usually bisexual (rarely

unisexual), usually perennial (rarely annual or biennial) herbs, suffrutices or

evergreen shrubs (rarely trees or epiphytes). Leaf succulents. Usually

xerophytes. Rarely aquatic (i.a. Crassula aquatica). Many species

produce adventitious roots from broken leaves; some species form bulbils along

leaf margins or in inflorescences.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza

usually absent. Roots usually fibrous. CAM physiology frequently present; acid

metabolism often Crassulaceae type (via

isocitrate). Mycorrhiza absent. Phellogen ab initio usually subepidermal

(sometimes cortical). Young stem with separate vascular bundles. Cortical

and/or medullary vascular bundles present or absent. Endodermis present or

absent. Secondary lateral growth usually normal (rarely anomalous). Vessel

elements (usually short) usually with simple (in Sedum rarely

reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform(-reticulate) or

alternate, simple pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform fibres

with simple pits, non-septate, or absent. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma

usually paratracheal scanty vasicentric. Wood elements often storied. Phloem

little developed. Sieve tube plastids S0 type, without starch or

protein inclusions. Nodes 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, unilacunar with one to three leaf

traces, or ≥3:≥3, trilacunar to multilacunar with several traces. Cork

tissue usually without resin. Prismatic crystals or crystal sand present or

absent.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or

multicellular, usually uniseriate or biseriate (sometimes furcate, stellate,

rarely arachnoid), vesicular hairs frequent; glandular hairs often frequent.

Leaves Usually alternate

(spiral) or opposite (in some species of Sedum verticillate), usually

simple (rarely pinnately or palmately compound), usually entire (rarely lobed),

often round in cross-section, usually succulent, with curved to flat ptyxis.

Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate.

Venation pinnate or palmate, camptodromous or reticulate. Stomata usually

anisocytic (rarely helicocytic with second ring of subsidiary cells outside

anisocytic cell configuration), often on both laminal surfaces (amphistomatic).

Cuticular wax crystalloids as platelets, rodlets (sometimes as elongated

rosettes, sometimes longitudinally furrowed), threads or lobate to smooth

platelets, chemically characterized by high amounts of triterpenoids.

Hydathodes abundant. Epidermis often with mucilage cells. Lamina usually

without palisade tissue. Mesophyll in succulent leaves often with outer

chlorenchyma grading into inner chlorophyll-poor water storage parenchyma.

Tanniniferous cells abundant. Crystals and druses frequent (sometimes crystal

sand). Leaf margin serrate, crenate or entire.

Inflorescence Usually terminal

(rarely axillary), thyrsoid, pleio-, di- or monochasium (cincinnus or corymb;

rarely panicle, raceme- or spike-like). Extrafloral nectaries rarely

(Adromischus) present.

Flowers Usually actinomorphic

(rarely zygomorphic). Hypanthium present. Hypogyny to half epigyny. Sepals

(three to) five (to 32), with imbricate aestivation, free or connate at base.

Petals (three to) five (to 32), with quincuncial, cochlear, contorted,

imbricate or valvate aestivation, free or entirely or partially connate into a

tube. Nectaries as abaxial usually scale-like or elongate (in

’Monanthes’ petaloid) outgrowths from carpel bases. Disc

absent.

Androecium Stamens usually

twice as many (sometimes as many) as petals, usually in two whorls,

obdiplostemonous (sometimes a single whorl, antesepalous). Filaments usually

free (sometimes connate at base), free from or (when sympetalous) adnate to

corolla tube (antepetalous stamens inserted somewhat higher up than

antesepalous stamens). Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate,

usually latrorse (rarely somewhat introrse), longicidal (dehiscing by

longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory, with uninucleate cells. Staminodia

usually absent (female flowers often with staminodia).

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tricolporate, shed as

monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate

infratectum, reticulate or rugulate, usually with striae.

Gynoecium Carpels (three to)

five to ten (to 32), as many as petals, antepetalous, usually free (sometimes

connate at base; in Crassula pageae entirely connate), sometimes

stipitate. Ovary superior to semi-inferior, unilocular (apocarpy). Stylodia

usually short (style rarely single, branched), usually with abaxial

nectariferous scale at base (secreting nectar through stomata). Stigmas small,

usually apical, capitate to punctate, papillate, usually Dry (sometimes Wet)

type. Pistillodia usually absent (male flowers often with pistillodia).

Ovules Placentation usually

marginal to laminar (rarely parietal). Ovule one to usually numerous per

carpel, anatropous, pendulous to horizontal, bitegmic, crassinucellar or (in

Crassuloideae) tenuinucellar. Micropyle usually bistomal (sometimes

exostomal or endostomal). Outer integument approx. two cell layers thick. Inner

integument two or three cell layers thick. Nucellar cap approx. four cell

layers thick. Hyponucellus (part of megasporangium present below developing

megagametophyte) strongly enlarged during development (Sedum and

Crassula types of megasporangium). Megasporangial apex sometimes

extending beyond outer integument; apical cell seemingly subpalisade.

Megasporocyte usually single (archespore sometimes multicellular). Megaspore

haustoria present in some species. Megagametophyte usually monosporous,

Polygonum type (in Hylotelephium disporous, Allium

type). Synergids sometimes haustorial (synergidal haustoria present). Antipodal

cells sometimes proliferating and haustorial. Micropylar suspensor haustorium

often well developed. Endosperm development usually cellular (rarely helobial

or nuclear; endosperm in e.g. Crassula aquatica reduced with chalazal

chamber of bicellular stage not dividing but becoming haustorial). Endosperm

haustorium chalazal. Embryogenesis caryophyllad.

Fruit Usually an assemblage of

follicles (rarely nutlets or a capsule; in Diamorpha secondarily fused

into a syncarp).

Seeds Aril absent. Testa

usually with papillae or longitudinal ridges. Outer wall of exotestal cells

thickened. Two layers crushed. Inner exotegmic layer pigmented. Perisperm not

developed. Endosperm sparse (thin layer surrounding hypocotyl), oily, or

absent. Suspensor uniseriate; basal suspensor cell with hypha-like haustorial

branches. Embryo small, straight, elongate, without chlorophyll. Plumule

absent. Cotyledons two, fleshy. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 4-≥22 –

Karyologically very variable; even the base number varying at least between x =

5 and x = 37 (especially in Sedum; S. suaveolens has the

highest haploid chromosome number among angiosperms: n = 320, 40x). Polyploidy

and aneuploidy frequently occurring.

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), methylated and non-methylated flavones,

acylated flavonol glycosides, cyanidin, red anthocyanins (frequent, also in

roots), toxic bufadienolides and similar substances (in Tylecodon,

Cotyledon and Kalanchoe), gallic acid, proanthocyanidins

(prodelphinidins), non-hydrolyzable tannins, pyrridine alkaloids and other

alkaloids, cyanogenic compounds, arbutin, acetophenones, galloylic esters and

isocitrate present. Sedoheptulose main reserve sugar. Aluminium accumulated in

some species. Ellagic acid and hydrolyzable tannins not found. Cyanogenesis via

isoleucine or valine.

Use Ornamental plants,

medicinal plants.

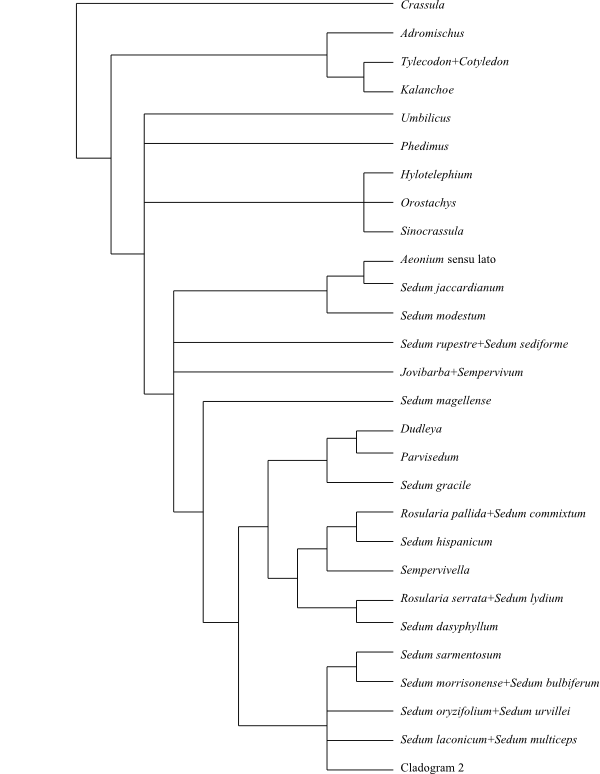

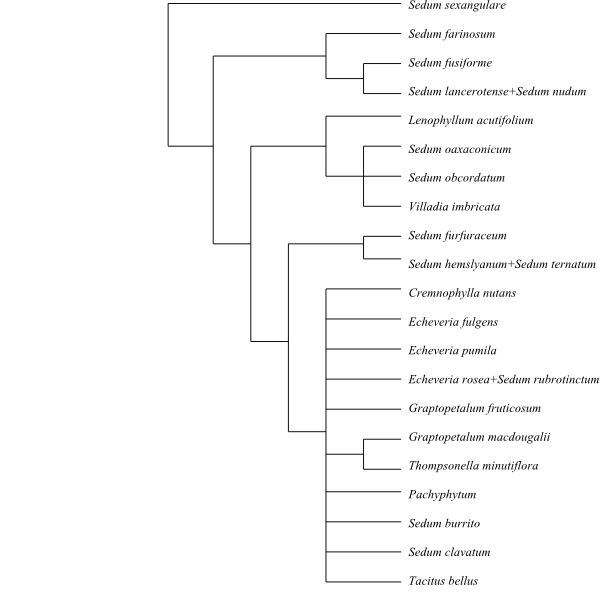

Systematics Crassulaceae are sister-group

to the clade [Aphanopetalaceae+[Tetracarpaeaceae+[Haloragaceae+Penthoraceae]]].

A possible topology is

[Crassuloideae+[Kalanchoideae+Sempervivoideae]].

Crassuloideae Burnett,

Outline Bot.: 736, 1092, 1131. Feb 1835 [’Crassulidae’]

2/200–210. Crassula

(200–210; almost cosmopolitan), Hypagophytum (1; H.

abyssinicum; Ethiopia). – Subcosmopolitan. The Tillaea clade of

Crassulais

nearly cosmopolitan and the only indigenous clade of Crassulaceae in Australia.

Leaves opposite. Leaf margin with hydathodes. Sepals four (or five). Petals

four (or five. Stamens four (or five). Anthers somewhat introrse. Carpels three

to nine. Median carpel in Tillaea clade abaxial. Ovules tenuinucellar.

Parietal tissue absent. Archespore sometimes multicellular. Megasporangial

epidermal cells often large. First division of micropylar endosperm cell

horizontal. Follicles dehiscing by apical pore. Testal cells often with a

single papilla and sinuous anticlinal walls. Tegmen absent. x = 7, 8.

[Kalanchoideae+Sempervivoideae]

Leaf margin usually with only one

(sub)apical hydathode. Anthers introrse only in early bud. Placentae sometimes

lobed. Parietal tissue present, one to four cell layers thick. First division

of micropylar endosperm cell vertical. Seeds costate.

Kalanchoideae A.

Berger in Engler et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam., ed. 2, 18a: 383. 3 Mai 1930

4/185–190. Adromischus

(c 26; southern Africa), Kalanchoe (c

125; eastern and southern Africa, Madagascar), Tylecodon (c

27; southern Africa), Cotyledon (9;

eastern and southern Africa, the Arabian Peninsula). – Africa, Madagascar,

the Arabian Peninsula. Shrubs or suffrutices (sometimes small trees).

Calciumoxalate present as crystal sand. Petals connate. Anther connective with

spherical prolongation. Megasporangial epidermal cells sometimes large. Seeds

with four to six costae and micropylar corona. x = 9, 17 (18). Toxic

bufadienolides (cardiac glycosides) present.

Sempervivoideae Arn.,

Botany: 112. 9 Mar 1832 [‘Sempervivae’]

24?/985–1.025. Usually perennial

(sometimes annual) herbs, shrubs, or suffrutices. Hylotelephium

clade Sinocrassula (7; S. ambigua, S.

densirosulata, S. diversifolia, S. indica, S.

longistyla, S. techinensis, S. yunnanensis; the

Himalayas, southwestern China; incl. Kungia?), Kungia (2;

K. aliciae, K. schoenlandii; southern China; in

Sinocrassula?), Meterostachys (1; M. sikokianus;

southern Korean Peninsula, southern Japan), Orostachys

(14; Europe, Central Asia, southern Siberia, Mongolia, China, the Korean

Peninsula, Japan), Hylotelephium

(c 33; temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere), Perrierosedum

(1; P. madagascariense; Madagascar). –

Umbiliceae Meisn., Plant. Vasc. Gen.: Tab. Diagn.

134, Comm. 98. 8-14 Apr 1838. Umbilicus (c

10; Europe, the Mediterranean to Iran, North and East African mountains),

Pseudosedum (7; P. acutisepalum, P. affine, P.

condensatum, P. koelzii, P. lievenii, P.

longidentatum, P. multicaule; Central Asia), Rhodiola

(60–65; alpine and mountain areas on the Northern Hemisphere, with their

highest diversity in the Himalayas, Tibet and western China), Phedimus (18;

Europe, temperate Asia). – Semperviveae Dumort.,

Fl. Belg.: 85. 1827. Sempervivum

(35–40; Europe, the Mediterranean, Morocco, western Asia). –

Sedeae Fr., Fl. Scan.: 97. 1835. Aeonium

(60–65; Macaronesia, the Mediterranean to Tanzania, the Arabian Peninsula),

Pistorinia (4; P. attenuata, P. brachyantha, P.

breviflora, P. hispanica; the Iberian Peninsula, Morocco,

Algeria), Rosularia (c

30; Europe, the Mediterranean, North Africa, Turkey to Central Asia and the

Himalayas), Prometheum (9; Europe, temperate Asia), Sedella

(4; S. congdonii, S. leiocarpa, S. pentandra, S.

pumila; southern Oregon, California), Dudleya (c 45;

southwestern United States, northwestern Mexico), ’Sedum’

(390–400; Europe, Africa, Asia, North to South America; non-monophyletic),

Villadia (c 45; Texas, Mexico, Central America, northwestern South

America to Peru), Lenophyllum (7; L. acutifolium, L.

guttatum, L. latum, L. obtusum, L. reflexum,

L. texanum, L. weinbergii; Texas, northeastern Mexico), Graptopetalum

(18; Arizona, Mexico), Thompsonella (7; T. colliculosa,

T. garcia-mendozae, T. minutiflora, T. mixtecana,

T. platyphylla, T. spathulata, T. xochipalensis;

Mexico), Echeveria

(150–170; southern United States, Mexico, Central America, the Andes, with

their highest diversity in Mexico), Pachyphytum

(17; Mexico). – Temperate, subtropical and alpine regions on the Northern

Hemisphere and southwards to Madagascar and Peru. Leaves usually alternate

(spiral; sometimes opposite). Flowers tetramerous to 32-merous. Petals usually

free (rarely connate). Carpels three to 32. Megasporangium prolonged, with

central vascular bundle. Follicle in Sedum rarely with

abaxial dehiscence. Seeds with more than six costae. Micropylar suspensor cell

vertically dividing. Suspensor often with compound plasmodesmata. x = 5 or

more. Pyrrolidine and piperidine alkaloids often present. Nonhydrolyzable

tannins not found. – All species of Echeveria

appear to be interfertile. The highly polyphyletic ‘Sedum’ occurs

in five of the seven main clades of Sempervivoideae.

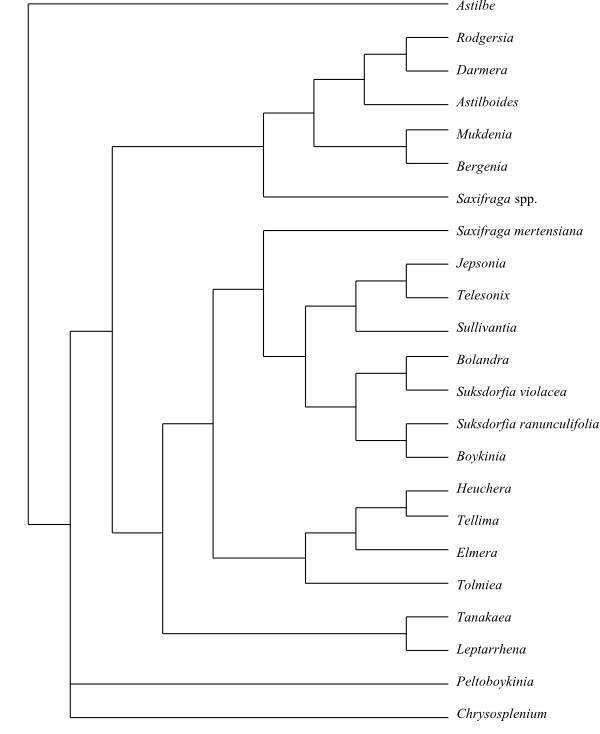

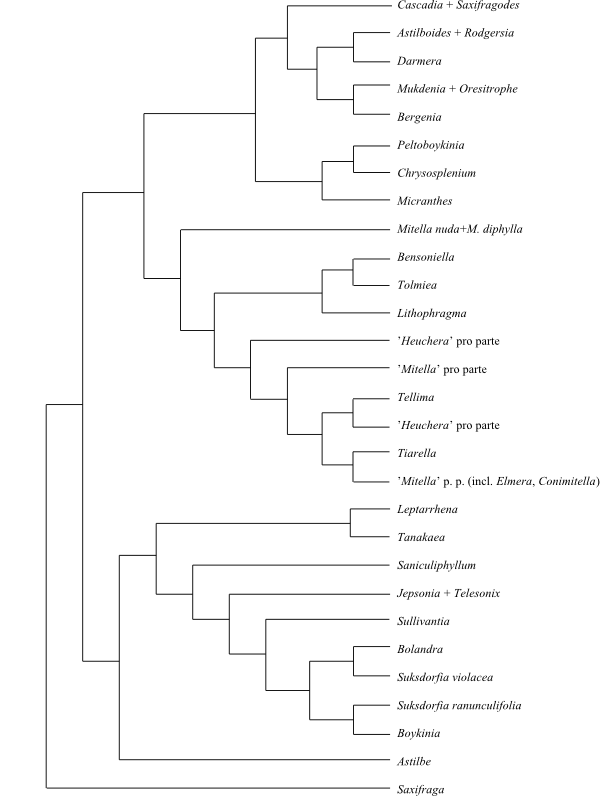

|

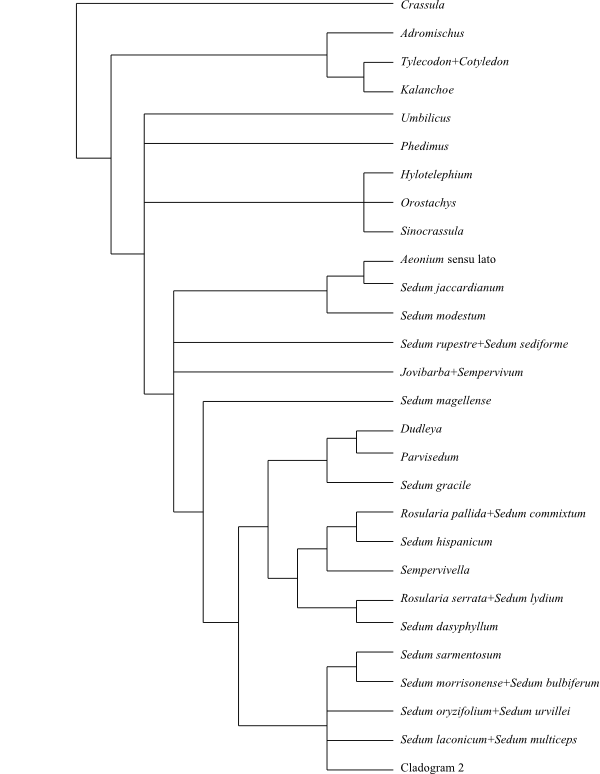

Cladogram 1 of Crassulaceae based on

DNA sequence (matK) data (Mort & al. 2001).

|

|

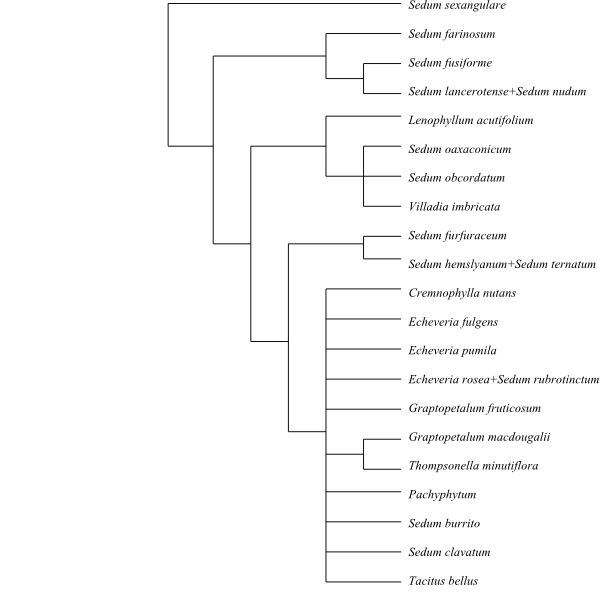

Cladogram 2 of Crassulaceae pro parte

based on DNA (matK) data (Mort & al. 2001).

|

Lindley, Nix. Plant.: 23. 17 Sep 1833

[‘Cynomorieae’], nom. cons.

Cynomoriales Burnett,

Outl. Bot.: 1100. Feb 1835

Genera/species 1/1

Distribution The

Mediterranean, Turkey, the Arabian Peninsula to Central Asia and Mongolia.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Usually monoecious (or

polygamomonoecious?; rarely bisexual), perennial herbs. Achlorophyllous root

holoendoparasites on Nitraria, different Cistaceae and Amaranthaceae,

Tamarix, and other halophytes.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza

absent. Root modified into fleshy tuberous haustorium, often with host tissue

incorporated; small lateral roots with root hairs abundant, arising from

rhizome. Phellogen absent. Vascular tissue much reduced. Secondary lateral

growth absent. Vessel elements with simple perforation plates; lateral pits?

Imperforate tracheary xylem elements? Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve

tube plastids Ss type? Calciumoxalate crystals abundant.

Trichomes Epidermal hairs

absent.

Leaves Alternate (spiral),

simple, entire, scale-like. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Venation absent?

Stomata anomocytic, rudimentary. Cuticular waxes? Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal,

clavate, on thick, fleshy inflorescence axis.

Flowers Actinomorphic, very

small. Epigyny. Tepals usually (one to) four or five (to eight), sepaloid, free

or connate at base (somewhat more differentiated in male flowers than in female

flowers), with ? aestivation. Pistillodial nectary present. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamen single.

Filament adnate at base to tepals. Anther dorsifixed, versatile,

tetrasporangiate, introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits).

Tapetum secretory. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains tricolporate to tricolporoidate,

shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine semitectate, with columellate

infratectum, reticulate.

Gynoecium Pistil probably

composed of one carpel (possibly two carpels). Ovary inferior, unilocular

(possibly pseudomonomerous). Style single, simple (with two vascular bundles),

long, with longitudinal furrow and with conduplicate distal part. Stigma

bilobate, type? Male flowers usually with one (sometimes two) yellow hypogynous

or epigynous pistillodium (stylodium) modified into nectary.

Ovules Placentation apical.

Ovule one per carpel/ovary, orthotropous, pendulous, ategmic to unitegmic,

almost crassinucellar. Integument five to seven cell layers thick, or absent.

Nucellar cap possibly present? Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum

type? Endosperm development cellular. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit An achene.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat

testal. Testa approx. seven cell layers thick, persistent, with little

thickened cells. Tegmen absent. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious,

thick-walled. Embryo small, poorly differentiated, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two.

Germination?

Cytology n = 12 – Karyotype

highly bimodal.

DNA

Phytochemistry Virtually

unknown. Tannins present. Triterpenes with HIV-inhibiting properties (Ma &

al. 1999, Nakamura 2004).

Use Medicinal plants, food.

Systematics

Cynomorium (1; C. coccineum; the Mediterranean from coastal

areas of southern Iberian Peninsula and northwestern Africa, Sahara to Egypt,

Turkey, the Arabian Peninsula to Central Asia and Mongolia).

Cynomorium was sister to

Rosaceae (Rosales) with weak support, according to Zhang

& al. (2009) and Moore & al. (2011) using sequences of the plastid

inverted repeat. The mitochondrial genes atp1 and coxI

indicate an inclusion into Sapindales (Barkman

& al. 2007), whereas Cynomorium belongs in Santalales,

according to Jian & al (2008). However, analyses of 18S rDNA and the

mitochondrial gene matR suggest placement of Cynomorium

within Saxifragales

(Nickrent 2002, Nickrent & al. 2005).

Cynomorium may have acquired genes

from different hosts via horizontal gene transfers (Nickrent 2002, Nickrent

& al. 2005, Barkman & al. 2007, Jian & al. 2008, Zhang & al.

2009), and this makes interpretations of its systematic position fairly

difficult.

Müller Argau in A.-P. de Candolle et A. L. P. P.

de Candolle, Prodr. 16(1): 1. med Nov 1869, nom. cons.

Daphniphyllales Pulle

ex Cronquist, Integr. Syst. Class. Fl. Pl.: 178. 10 Aug 1981;

Daphniphyllanae Takht., Divers. Classif. Fl. Pl.:

140. 24 Apr 1997

Genera/species 1/c 30

Distribution Southwestern

India, Sri Lanka, the Himalayas, southern Tibet, Assam, East Asia to Taiwan,

the Korean Peninsula and Japan, Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea, Solomon

Islands, tropical Australia, with their largest diversity in Yunnan.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Usually dioecious

(rarely polygamodioecious), evergreen trees or shrubs. Branches provided with

numerous lenticels.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen?

Medulla often septated by diaphragms. Pericyclic fibres absent. Vessel elements

with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits opposite to scalariform,

simple and/or bordered pits, non-septate. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements

tracheids with bordered pits, non-septate? Wood rays uniseriate or

multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or banded.

Tyloses common. Sieve tube plastids Ss type, with approx. five globular starch

grains. Nodes? Chambered calciumoxalate crystals present in some species.

Trichomes Hairs absent.

LeavesUsually alternate

(spiral; rarely opposite), simple, entire, with flat ptyxis. Stipules and leaf

sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundles? Venation pinnate. Stomata usually

paracytic (sometimes anomocytic or laterocytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids as

clustered tubuli (Berberis type), chemically dominated by

nonacosan-10-ol. Mesophyll with calciumoxalate druses. Leaf margin usually

entire.

Inflorescence Axillary,

usually raceme.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small.

Hypogyny. Sepals two to six, with imbricate aestivation, very small, or absent.

Petals absent. Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens five to 12

(to 24), usually as many as or twice the number of sepals. Filaments short,

free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile,

tetrasporangiate, latrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal valves);

connective often somewhat prolonged. Tapetum secretory. Female and male flowers

sometimes with staminodia.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tricolpate (rarely

tricolporoidate), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with

columellate infratectum, microperforate, psilate or verrucate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

usually two (rarely three or four) connate carpels. Ovary superior,

incompletely bilocular (rarely trilocular or quadrilocular). Stylodia usually

two (rarely three or four), short, recurved or circinate, connate at base.

Stigmas relatively massive, decurrent, with multicellular appendages,

non-papillate, Dry type. Male flowers sometimes with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation apical to

axile or parietal. Ovules (one or) two per carpel, anatropous, pendulous,

epitropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle exostomal, Z-shaped (zig-zag)?

Outer integument three to six cell layers thick. Inner integument four or five

cell layers thick. Hypostase present. Megagametophyte monosporous,

Polygonum type. Synergids with a filiform apparatus. Endosperm

development cellular. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis? Polyembryony

sometimes occurring.

Fruit A usually one-seeded

(rarely two-seeded) drupe, often with persistent stylodia and staminodia.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa

persistent, thin-walled, crushed. Exotegmen? Endotegmen with tannins, and

thickened and often sclerotized and cutinized cell walls. Perisperm thin, with

protein crystals. Endosperm copious, oily and proteinaceous. Embryo small,

straight, apical, well differentiated, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two, as wide as

radicula. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 16

DNA Mitochondrial intron

coxII.i3 lost?

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(quercetin, apigenin, luteolin, etc.), Group I carbocyclic iridoids (e.g.

asperuloside, daphniphylloside), hydrolyzable tannins, and unique triterpene

(squalene) alkaloids of the daphniphylline group (daphniphylline,

codaphniphylline etc.) present. Myricetin? Ellagic acid, proanthocyanidins,

condensed tannins, and cyanogenic compounds not found. Aluminium

accumulated.

Use Ornamental plants.

Systematics

Daphniphyllum (c 30; the Western Ghats in southwestern India, Sri

Lanka, Missuri to Bhutan in southern Himalayas, southern Tibet, Khasia Hills in

Assam, China, the Korean Peninsula and Japan, Taiwan, Southeast Asia, Malesia

to New Guinea, Solomon Islands, tropical Australia, with their largest

diversity in Yunnan).

Daphniphyllum is probably sister to Cercidiphyllum

(Cercidiphyllaceae).

de Candolle in de Lamarck et A. P. de Candolle,

Fl. Franç., ed. 3, 4(2): 405. 17 Sep 1805 [’Grossulariae’], nom.

cons.

Grossulariales DC. ex

Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 236. Jan-Apr 1820

[‘Grossulariae’]; Ribesiaceae Marquis,

Esq. Règne Vég.: 66. 15-22 Jul 1820 [’Ribesioïdeae’]

Genera/species 1/180–200

Distribution Temperate parts

of Eurasia, the Mediterranean, northeastern Africa, North America to southern

Chile.

Fossils Leaves similar to

Ribes are known from Eocene and younger sediments in North America.

Habit Usually bisexual

(sometimes dioecious), usually deciduous (rarely evergreen) shrubs, upright,

creeping (often with subterranean stems) or occasionally somewhat climbing;

branches differentiated into long shoots and short shoots. Leaves sometimes

modified into spines.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

ab initio outer-cortical to pericyclic. Subterranean stems with well developed

endodermis. Pericyclic fibres absent. Vessel elements usually with scalariform

(rarely simple) perforation plates; lateral pits usually alternate (sometimes

scalariform), simple or bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements

fibre tracheids with simple or bordered pits, septate or non-septate (also

vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or

heterocellular. Axial parenchyma usually absent (rarely apotracheal diffuse or

paratracheal scanty or banded). Sieve tube plastids Ss type. Nodes 1:1,

unilacunar with one leaf trace, or 3:3, trilacunar with three traces.

Tanniniferous cells abundant. Non-lignified stem tissues with numerous

cystoliths. Calciumoxalate druses present.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or

multicellular, stalked or unstalked, uniseriate or branched, with or without

glandular apex, often peltate-lepidote glandular hairs; epidermal prickles

frequent at nodes and internodes.

Leaves Alternate (spiral),

simple or almost palmately compound, usually lobed (rarely entire), usually

with conduplicate-plicate (rarely convolute) ptyxis. Stipules intrapetiolar,

membranous, or absent; leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection

arcuate?; petiole bundles connate. Venation palmate. Stomata anomocytic

(paracytic?). Cuticular waxes? Domatia abaxial, as pockets. Druses present in

parenchyma and collenchyma. Tanniniferous cells numerous. Leaf margin usually

coarsely serrate; leaf teeth with hydathodes.

Inflorescence Terminal,

raceme, usually pendent (sometimes erect).

Flowers Actinomorphic, small.

Pedicel articulated. Hypanthium present, with basal nectaries. Epigyny or

almost epigyny. Sepals usually five (rarely four), with imbricate or subvalvate

aestivation, often petaloid, persistent, usually recurved (sometimes connivent

into a tube), free. Petals (in reality staminodia?) usually five (rarely four),

with open or imbricate aestivation, scale-like to subulate, persistent, free

(rarely absent). Nectariferous disc often quinquelobate.

Androecium Stamens usually

five (rarely four), antesepalous, alternipetalous. Filaments filiform, inserted

on top of hypanthium, free, adnate to sepals (free from petals?). Anthers

usually basifixed (sometimes dorsifixed), non-versatile, tetrasporangiate,

introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective sometimes

with apical nectary. Tapetum secretory. Female flowers with staminodia.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains (5–)8–14-pantoporate or

zonocolporate (rarely pentacolpodiorate), shed as monads, bicellular at

dispersal. Ectoapertures present (rugulate surfaces surrounding endoapertures).

Exine pertectate, with columellate? infratectum, rugulate, punctate or

spinulate.

Gynoecium Pistil usually

composed of two paracarpous, connate and usually median (sometimes transverse)

carpels. Ovary inferior or almost inferior, unilocular. Style single, simple or

bifid, or stylodia two, free. Stigmas two, capitate, non-papillate, Wet type.

Male flowers with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation parietal

(with two somewhat intruding placentae). Ovules four to more than 100 per

ovary, anatropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle exostomal. Outer

integument three to five cell layers thick, with tanniniferous outer epidermal

cells. Inner integument two or three cell layers thick. Funicular obturator

present. Parietal tissue three or four cell layers thick. Hypostase present.

Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development

usually cellular (sometimes helobial or nuclear?). Endosperm haustorium

chalazal. Embryogenesis irregular.

Fruit A many-seeded berry-like

fruit with persistent perianth and staminal remnants.

Seeds Funicular aril

surrounding entire or parts of seed. Seed coat endotestal. Exotesta

mucilaginous (myxotesta); exotestal cells palisade, large with thin walls;

epidermal cells large and pulpy. Endotesta hard; endotestal cells small,

cuboid, with calciumoxalate crystals, and with radial and inner walls

lignified. Tegmic cells elongate, tanniniferous. Perisperm not developed.

Endosperm copious, oily, proteinaceous and with hemicellulose, with somewhat

thickened walls. Embryo small, straight, well differentiated, without

chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, with main vein ending in hydathodal tooth.

Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 8 (16)

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), cyanidin, delphinidin, mono- and

sesquiterpenes, ellagic acid, ellagitannins, and tyrosine-derived cyanogenic

compounds present. Iridoids not found. Aluminium accumulated in some

species.

Use Ornamental plants, fruits,

tea (leaves from Ribes nigrum), medicinal plants.

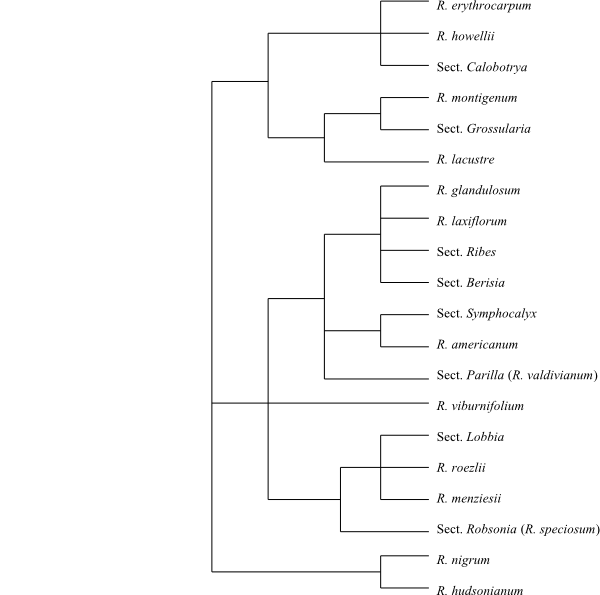

Systematics Ribes

(180–200; Europe, the Mediterranean, northeastern Africa, temperate Asia,

North and Central America, the Pacific coast of South America, the Andes south

to Tierra del Fuego).

Ribes is

sister to Saxifragaceae.

|

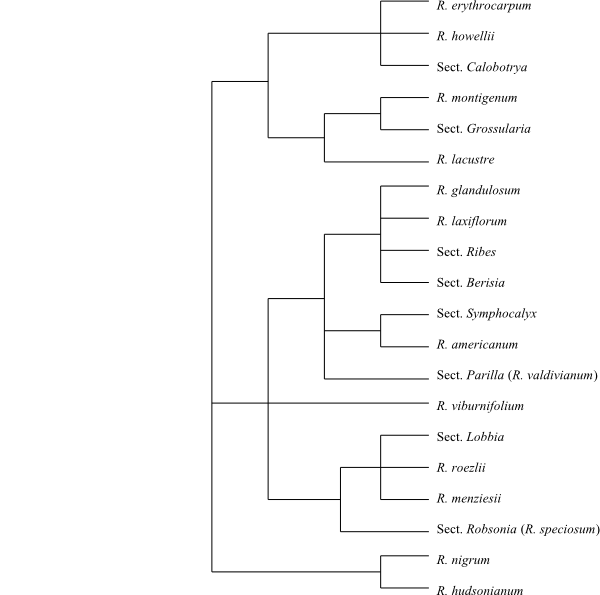

50% majority rule consensus tree of Ribes

based on DNA sequence data (Messinger & al. 1999).

|

Brown in M. Flinders, Voy. Terra Austral. 2: 549.

19 Jul 1814 [’Halorageae’], nom. cons.

Cercodiaceae Juss. in

F. Cuvier, Dict. Sci. Nat. 7: 441. 24 Mai 1817 [‘Cercodianae’];

Haloragales Link, Handbuch 2: 52. 4-11 Jul 1829

[’Halorageae’]; Myriophyllaceae Schultz

Sch., Nat. Syst. Pflanzenr.: 324. 30 Jan-10 Feb 1832

[’Myriophylleae’]; Haloragineae Engl.,

Syllabus, ed. 2: 162. Mai 1898 [‘Halorrhagidineae’]

Genera/species 8–9/c 120

Distribution Largest diversity

on the Southern Hemisphere, particularly in Australia; Myriophyllum

cosmopolitan; Proserpinaca in North America and the West Indies.

Fossils Obispocaulis

myriophylloides and Tarahumara sophiae from the Campanian to the

Maastrichtian of Mexico have both been assigned to either Haloragaceae or very close to

that clade. Tarahumara had unisexual epigynous flowers with four

basally connate uniovulate carpels, and a drupaceous fruit.

Obispocaulis is represented by fossil stems containing aerenchyma and

bearing adpressed leaves. Cenozoic pollen and fruits of Haloragaceae are frequent in

both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. Fossils of Proserpinaca

are known from pre-Pliocene layers in Europe.

Habit Usually monoecious or

polygamomonoecious (rarely bisexual or dioecious), perennial or annual herbs,

suffrutices or evergreen small shrubs (‘Haloragodendron’ consists

of shrubs and small trees). Numerous species are aquatic, other representatives

are amphibious, hygrophytes or terrestrial mesophytes. Myriophyllum in

the Northern Hemisphere produces turions (condensed reproductive and

hibernating shoots). The main root in aquatic and amphibious species is

replaced by adventitious roots (without root hairs), anchoring the plant to the

substrate (adventitious roots in Haloragis inserted between the

leaves).

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen?

Primary cortex with numerous aerial cavities (especially in aquatic species).

Primary vascular tissue strongly reduced in aquatic species. Endodermis

significant especially in aquatic species. Secondary lateral growth normal or

absent. Vessel elements with simple perforation plates; lateral pits?

Imperforate tracheary xylem elements ?, with simple pits

(Glischrocaryon). Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular

or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids Ss type. Nodes 1:1,

unilacunar with one leaf trace. Calciumoxalate crystals often present in

hair-shaped cortical cells.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or

multicellular, uniseriate, often with silica, or absent.

Leaves Usually opposite or

verticillate (sometimes alternate, spiral), simple or compound (often pinnately

compound), entire or often finely lobed, with conduplicate-flat ptyxis (in

Myriophyllum and Proserpinaca heterophylly). Stipules very

small or absent; leaf sheath absent. Colleters present? Petiole vascular bundle

transection arcuate? Venation pinnate (or leaves one-veined). Stomata usually

anomocytic (often absent). Cuticular wax crystalloids usually absent (rarely as

parallel grouped platelets, Hypericum type). Leaf margin serrate or

entire, eglandular.

Inflorescence Terminal or

axillary, thyrso-paniculate, thyrsoid, fasciculate etc., or raceme- or

spike-like, or flowers solitary, axillary. Floral prophylls (bracteoles)

present or absent.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small.

Epigyny. Sepals usually four (in Proserpinaca three, rarely two), with

valvate aestivation, persistent (absent in female flowers of

Myriophyllum). Petals usually four (in Proserpinaca three,

rarely two), with imbricate aestivation, caducous (usually absent in

Proserpinaca and female flowers in Myriophyllum and

Laurembergia). Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens usually

(two to) four or 4+4, as many as or twice the number of sepals (when four then

antesepalous). Filaments short, narrow, free from each other and from tepals.

Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse, longicidal

(dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective sometimes slightly prolonged.

Tapetum secretory. Antesepalous staminodia present in some species of

Gonocarpus.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains 4–6(–20)-colpate or

4–6(–20)-porate, shed as monads, usually tricellular (rarely bicellular) at

dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum, microperforate and

beset with small supratectal processes.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

usually four (rarely two or three) connate carpels; carpels antepetalous or

median carpel adaxial. Ovary inferior, (unilocular to) quadrilocular (septa

sometimes poorly developed, absent in Laurembergia and most species of

Glischrocaryon). Stylodia separate, clavate, somewhat swollen at base

(sometimes absent). Stigmas capitate or penicillate, papillate, Dry type.

Pistillodium?

Ovules Placentation apical.

Ovules one or two (one aborting) per carpel, anatropous or hemianatropous,

pendulous, usually apotropous (sometimes epitropous), bitegmic, crassinucellar

(or tenuinucellar?). Micropyle endostomal (Myriophyllum). Outer

integument two or three cell layers thick. Inner integument approx. two cell

layers thick. Parietal tissue two or three cell layers thick. Archesporial cell

hypodermal (Myriophyllum). Funicular obturator poorly developed or

absent. Hypostase often present. Nucellar cap often present. Megagametophyte

monosporous, Polygonum type. Synergids with a filiform apparatus.

Antipodal cells persistent. Endosperm development usually cellular (in

Laurembergia and some species of Myriophyllum nuclear).

Haustorial suspensor present. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis

caryophyllad.

Fruit A one- to four-seeded

nut (in Proserpinaca three-seeded), a drupe with one- to four-seeded

pyrene (in Meziella) or a schizocarp with two to four nut-like

mericarps (in Myriophyllum).

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat

exotestal. Exotesta (sometimes also hypodermal layer) persistent, with

thin-walled cells; other parts of testa and tegmen degrading and crushed.

Perisperm not developed. Endosperm usually copious, starchy, oily. Embryo

usually large, straight, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two. Germination

phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = (6) 7 (8) 14, 28,

42, 56 – Polyploidy occurring.

DNA Mitochondrial intron

coxII.i3 lost (Haloragis).

Phytochemistry Flavones,

pelargonidin (in leaves), cyanidin, ellagic and gallic acid, tannins,

myriophyllin (in hair glands of Myriophyllum), cyanogenic compounds,

saponins, and coumaric acid present. Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin)?

Use Ornamental plants,

aquarium plants (Myriophyllum).

Systematics Glischrocaryon

(5; G. angustifolium, G. aureum, G. behrii, G.

flavescens, G. roei; southern Western Australia, southern South

Australia, New South Wales, Victoria; incl. Haloragodendron?),

‘Haloragodendron’ (5–6; H. baeuerlenii, H.

gibsonii, H. glandulosum, H. lucasii, H.

monospermum, H. racemosum; southwestern Western Australia,

southeastern New South Wales, eastern Victoria, Tasmania; paraphyletic; in Glischrocaryon?);

Proserpinaca (4; P. amblygona, P. intermedia, P.

palustris, P. pectinata; southeastern United States, the West

Indies), Meionectes (2; M. brownii, M. preissii;

southwestern Western Australia, southeastern South Australia, southern

Victoria, Tasmania), Trihaloragis (1; T. hexandra;

southwestern Western Australia), Haloragis (17?; Australia, New

Caledonia, New Zealand, Rapa Island, Juan Fernández), Gonocarpus (c

40; Southeast Asia and Malesia to Japan, Australia and New Zealand),

Laurembergia (4; L. minor, L. repens, L.

tetrandra, L. veronicifolia; tropical and subtropical regions on

both hemispheres), Myriophyllum

(c 70; cosmopolitan, with their highest diversity in Australia).

Haloragaceae are sister-group

to Penthorum (Penthoraceae).

The Haloragodendron clade (probably

including Glischrocaryon)

is sister to the remaining Haloragaceae. The crown clade

is not completely resolved, since Proserpinaca and Meionectes

are parts of a basal trichotomy together with the remainder.

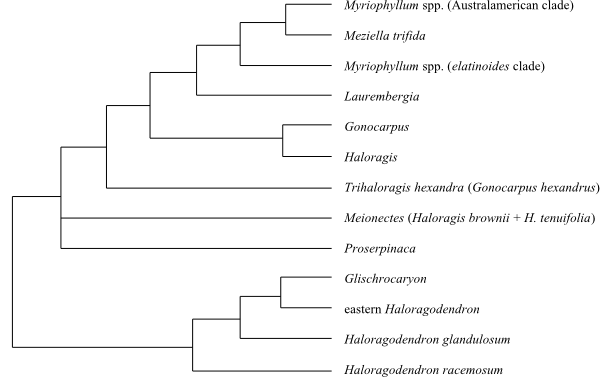

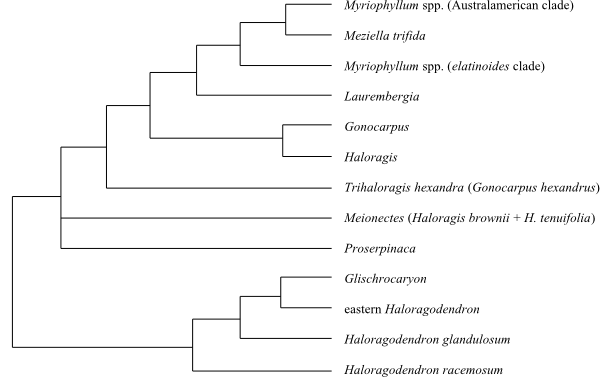

|

Majority rule consensus tree (simplified) from

Bayesian analysis of Haloragaceae based on

DNA sequence data (Moody & Les 2007).

|

Brown in C. Abel, Narr. Journey China: 374. 15

Aug 1818 [‘Hamamelideae’], nom. cons.

Fothergillaceae

Nutt., Gen. N. Amer. Pl. 1: 108. 14 Jul 1818 [‘Fothergilleae’];

Fothergillales Link, Handbuch 2: 445. 4-11 Jul 1829

[’Fothergilleae’]; Hamamelidales Link,

Handbuch 2: 4. 4-11 Jul 1829 [’Hamamelideae’];

Parrotiaceae Horan., Prim. Lin. Syst. Nat.: 79. 2 Nov

1834 [‘Parrotiaceae (Hamamelideae)’];

Hamamelidopsida Brongn., Enum. Plant. Mus. Paris:

xxix, 109. 12 Aug 1843 [’Hamamelineae’];

Bucklandiaceae J. Agardh, Theoria Syst. Plant.: 155.

Apr-Sep 1858 [’Bucklandieae’], nom. illeg.;

Disanthaceae Nakai, Chosakuronbun Mokuroku [Ord. Fam.

Trib. Nov.]: 246. 20 Jul 1943; Rhodoleiaceae Nakai,

Chosakuronbun Mokuroku [Ord. Fam. Trib. Nov.]: 246. 20 Jul 1943;

Exbucklandiaceae Reveal et Doweld in Novon 9: 552. 30

Dec 1999; Hamamelidineae Thorne et Reveal in Bot.

Rev. (Lancaster) 73: 91. 29 Jun 2007

Genera/species 26/110–111

Distribution Eastern and

southern Africa, Madagascar, southern Turkey, southeastern Trans-Caucasus,

northern Iran, western and eastern Himalayas, Assam, Manipure, East and

Southeast Asia to the Korean Peninsula and Japan, Malesia to New Guinea,

northeastern Australia (Queensland), eastern North America, Central America,

northeastern South America.

Fossils Allonia

decandra from the Late Santonian of Georgia (the United States) is a

pentamerous male flower with connate sepals and two staminal whorls, tricolpate

pollen having reticulate exine and columellate infratectum, and with an adaxial

lobate (nectariferous?) disc. Allonia seems to be sister-group to

Maingaya. Androdecidua endressii is another pentamerous

staminate flower from the Late Santonian of Georgia. Numerous fossils

(especially leaves and seeds) of Hamamelidaceae are known

from the Cenozoic. Seeds and bilocular fruits of Rhodoleia have been

found in Maastrichtian to Miocene layers in Europe.

Habit Usually bisexual

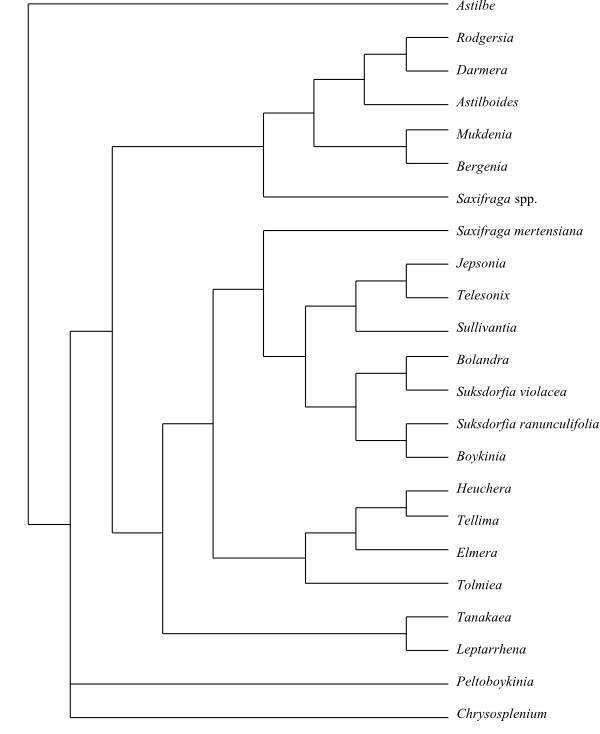

(sometimes monoecious, andromonoecious or polygamomonoecious), evergreen or

deciduous trees or shrubs.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

ab initio superficial. Primary vascular tissues as a cylinder, without separate

bundles. Vessel elements with usually scalariform (sometimes reticulate)

perforation plates; lateral pits usually opposite to scalariform (rarely

alternate), simple pits. Vestured pits sometimes present. Imperforate tracheary

xylem elements tracheids or fibre tracheids with bordered pits, non-septate.

Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial

parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal scanty

(or unilateral), or absent. Tyloses sometimes abundant. Sieve tube plastids Ss

type, with five (to ten) starch grains. Nodes usually 3:3, trilacunar with

three leaf traces (in Chunia and Mytilaria 5:5, pentalacunar

with five traces). Medulla in Mytilaria with resiniferous secretory

canals. Branched sclereids frequent. Some species possess secretory canals.

Parenchyma usually with prismatic calciumoxalate crystals.

Trichomes Hairs usually

multicellular (sometimes unicellular), often early sclerified, usually stellate

or tufted (sometimes uniseriate).

Leaves Usually alternate

(usually distichous, sometimes spiral; rarely opposite), simple, entire, with

conduplicate-flat or conduplicate-plicate ptyxis. Stipules usually caducous

(sometimes cauline); leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection

usually annular (rarely arcuate; petiole sometimes with adaxial bundle).

Venation usually palmate or with stout veins at base (rarely pinnate),

eucamptodromous or actinodromous and brochidodromous or craspedodromous.

Stomata usually paracytic (sometimes laterocytic), often only on adaxial side

of lamina. Cuticular wax crystalloids usually absent (rarely as irregular

platelets, or as clustered tubuli of Berberis type, chemically

dominated by nonacosan-10-ol). Domatia rarely present. Epidermis with or

without mucilage cells. Mesophyll with calciumoxalate crystals and usually

sclerenchymatous idioblasts with sclereids of different appearance

(brachysclereids, columnar, etc.). Leaf margin usually serrate (rarely entire);

leaf teeth often fothergilloid (with transparent glandular apex; gland often

absent).

Inflorescence Terminal or

axillary, thyrse, botryoid, panicle, spike-, catkin- or head-like (rarely

raceme; in Rhodoleia pendant capitulate pseudanthium with involucre

consisting of bracts).

Flowers Usually actinomorphic.

Hypanthium present or absent. Usually epigyny (rarely hypogyny). Sepals (two

to) four or five (to seven), usually with imbricate aestivation, usually free

(rarely connate), often persistent (rarely absent). Petals (two to) four or

five, with open or valvate (or imbricate) aestivation, adaxially circinate,

usually band-like, often spirally twisted, sometimes stipitate, caducous, free

(rarely absent). Nectaries as an intrastaminal annular nectariferous disc or

staminodial nectaries (in Hamamelis), at petal bases (in

Disanthus) or as nectariferous glands around filament (in

Rhodoleia).

Androecium Stamens (one to)

four or five (to 24), in one or two whorls, often as many as sepals,

antesepalous. Filaments free from each other and from tepals. Anthers usually

basifixed, non-versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (rarely disporangiate),

latrorse or introrse, longicidal (usually dehiscing by one or two valves or

slits; rarely by basal pore); connective usually more or less prolonged.

Tapetum secretory, with uni-, bi- or multinucleate cells. Staminodia

antepetalous, sometimes alternating with fertile stamens, or absent.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tricolpate (rarely

tetracolpate, pantocolpate, hexarugate,polyrugate or polyforate), shed as

monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine semitectate, with columellate

infratectum, reticulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

usually two (rarely three) partially or entirely connate carpels. Ovary usually

inferior (rarely superior), usually bilocular (rarely trilocular). Stylodia

usually two (rarely three), long, free or connate below. Stigmas terminal or

decurrent, with multicellular appendages, non-papillate, Dry type. Male flowers

often with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation axile to

apical. Ovule usually one or several (rarely numerous) per carpel, anatropous,

usually pendulous (along carpellary edges when numerous), apotropous to

epitropous (half epitropous, half apotropous), bitegmic, crassinucellar.

Micropyle endostomal or bistomal, sometimes Z-shaped (zig-zag). Outer

integument usually six to twelve (rarely two) cell layers thick. Inner

integument two or three cell layers thick. Hypostase present. Parietal tissue

usually eight to ten cell layers thick. Nucellar cap sometimes two cell layers

thick. Archespore usually unicellular (rarely multicellular). Megagametophyte

monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development usually nuclear (at

least in Parrotiopsis cellular). Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis

chenopodiad (Distylium, Hamamelis) or solanad

(Parrotiopsis).

Fruit A loculicidal and/or

septicidal double-walled capsule with coriaceous or lignified exocarp and

lignified or corneous endocarp, often with persistent calyx (in

Rhodoleia a syncarp with capsular unities).

Seeds Aril absent. Hilum

large. Seed coat (meso)testal. Testa usually thick, hard, multiplicative,

shining and often two-coloured, winged or unwinged. Exotestal cells usually

thickened. Mesotesta massive, usually consisting of sclerotized fibrous cells.

Tegmen not included in mature seed coat; tegmic cells tanniniferus. Perisperm

more or less developed. Endosperm usually sparse, oily. Embryo straight,

usually small, well differentiated. Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar.

Polyembryony sometimes occurring.

Cytology n = 8, 12 –

Polyploidy occurring in some species.

DNA Mitochondrial intron

coxII.i3 lost. Plastid gene rpl22 absent.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), flavone-C-glycosides, cyanidin,

delphinidin, ellagic acid, and tannins present. Chalcones, alkaloids, and

cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Ornamental plants,

medicinal plants (also healing substances etc. from Hamamelis

virginiana), timber.

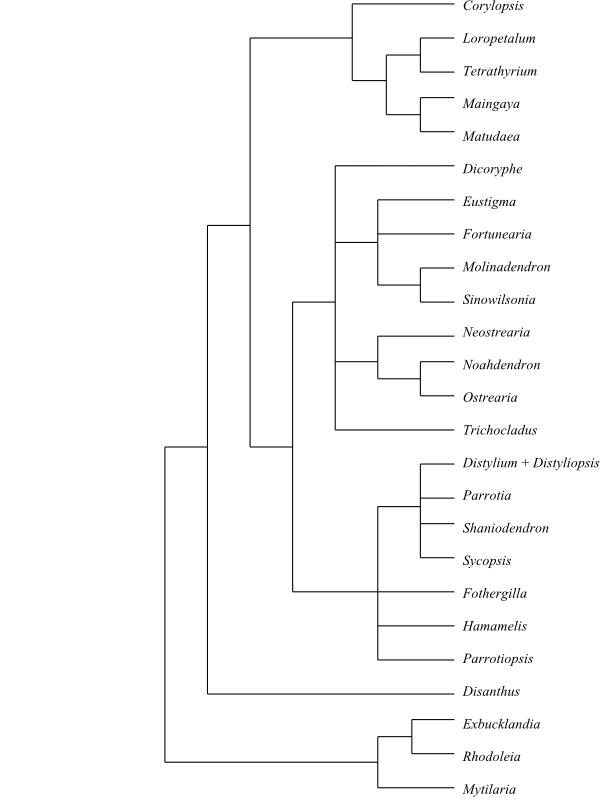

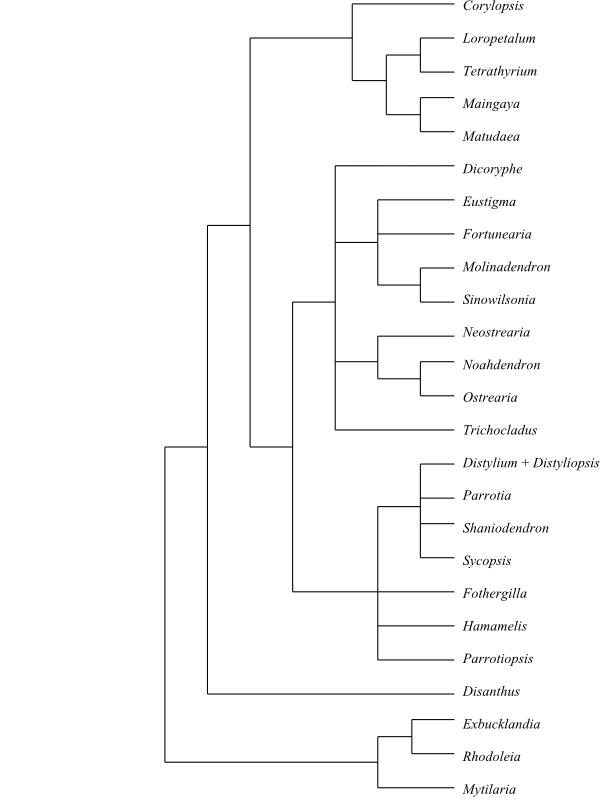

Systematics Hamamelidaceae are

sister-group to the clade [Cercidiphyllaceae+Daphniphyllaceae].

Exbucklandioideae are sister to the

remainder.

Exbucklandioideae (A.

Reinsch) H. T. Chang in Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Sunyatseni 1973(1): 54. Nov

1973

3/10. Exbucklandia (3; E.

longipetala, E. populnea, E. tonkinensis; Assam, eastern

Himalayas, southern China, the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra), Rhodoleia

(6; R. championii, R. forrestii, R. henryi, R.

macrocarpa, R. parvipetala, R. stenopetala; southern

China, Southeast Asia to Sumatra), Mytilaria (1; M.

laosensis; Guangxi, Laos). – Assam to Southeast Asia and southern China,

West Malesia. Inflorescence usually capitate. Epigyny or half epigyny. Petals

sometimes absent. Micropyle in Exbucklandia with partially prolonged

outer integument. Outer integument in Exbucklandia two cell layers

thick. Seed coat in Exbucklandia and Rhodoleia winged. Only

exotestal cells thickened. n = 8, 12.

[Disanthoideae+Hamamelidoideae]

Disanthoideae Harms in

Engler et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam., ed. 2, 18a: 314. 3 Mai 1930

1/1. Disanthus (1; D.

cercidifolius; Japan). – Hypogyny. Nectaries present at petal bases.

Anthers dehiscing with longitudinal slits. n = 8.

Hamamelidoideae