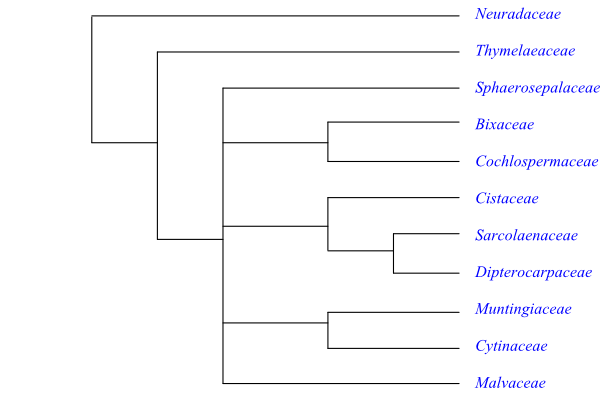

Cladogram of Malvales based on DNA sequence data (Stevens 2001 onwards, May 2012 version).

Habit Usually bisexual (rarely monoecious, andromonoecious, trimonoecious, polygamomonoecious, dioecious, androdioecious, or gynodioecious), evergreen or deciduous trees, shrubs or suffrutices (rarely lianas), perennial, biennial or annual herbs. Some species are xerophytic.

Vegetative anatomy Ectomycorrhiza frequent. Phellogen ab initio epidermal, subepidermal or outer-cortical. Vessel elements usually with simple (sometimes scalariform) perforation plates; lateral pits usually alternate (sometimes scalariform or opposite), simple or bordered pits. Vestured pits sometimes present. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids, fibre tracheids or libriform fibres with simple or bordered pits, usually non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal, aliform, lozenge-aliform, winged-aliform, confluent, reticulate, unilateral, vasicentric, or banded (sometimes scanty or scalariform), or absent. Tile cells often present. Secondary phloem often stratified into soft parenchymatous and harder fibrous layers; phloem rays cuneate. Sieve tube plastids usually S0 or Ss type (sometimes Pcs type). Nodes usually 3:≥3, trilacunar with three or more leaf traces (sometimes 1:1, unilacunar with one trace, rarely ≥5:≥5, penta- or multilacunar with five or more traces). Lysigenic or schizogenic mucilage ducts, cavities and cells often present (especially in epidermis, cortex and medulla). Heartwood sometimes with gum-like deposits. Silica bodies present in some species. Cortex with or without cristarque cells. Prismatic or acicular calciumoxalate crystals frequent (usually in groups), sometimes druses, styloids, or crystal sand.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate or multiseriate, simple or branched, fasciculate, lanate, bristle-like, furcate, multi-armed, stellate, peltate, lepidote; glandular hairs (also peltate) often abundant.

Leaves Usually alternate (spiral or distichous; sometimes opposite, rarely verticillate), simple or palmately compound (rarely unifoliolate), entire or palmately lobed, with conduplicate to plicate, supervolute, involute or curved ptyxis. Stipules often intrapetiolar, usually well developed, sometimes large and foliaceous, often early caducous (rarely reduced); leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate or annular; petiole sometimes also with inner ring of bundles (sometimes with medullary bundles), or petiole anatomy simple. Venation pinnate or palmate, brochidodromous, eucamptodromous, actinodromous or acrodromous (sometimes parallelodromous); one vein proceeding into non-glandular apex. Stomata usually anomocytic (sometimes anisocytic, paracytic, tetracytic, cyclocytic or helicocytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids as rosettes of platelets (Fabales type) or absent. Domatia as pockets or hair tufts (rarely pits) or absent. Epidermis and mesophyll with or without mucilaginous idioblasts. Mesophyll often with sclerenchymatous idioblasts. Parenchyma sometimes with schizogenous secretory ducts. Cystoliths sometimes present. Leaf margin serrate (sometimes glandular-serrate), crenate, sinuate or entire; leaf teeth often malvoid.

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, cymose of various shape, thyrsoid, panicle, raceme-like (sometimes raceme, head, or racemose panicle), or flowers solitary. Inflorescence often composed of cymose modified ’bicolor’ units, consisting of one terminal flower with three bracts, two of which having one cymose partial inflorescence each, with normal number of floral prophylls (bracteoles), and lowermost bract without axillary partial inflorescence. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) sometimes absent.

Flowers Usually actinomorphic (rarely zygomorphic or asymmetrical). Epicalyx, usually consisting of three bracts, sometimes present. Usually hypogyny (rarely epigyny or half epigyny). Sepals (three to) five (or six), usually with valvate (sometimes imbricate or contorted) aestivation, persistent or caducous, sometimes petaloid, free or more or less connate in lower part. Petals (three to) five (to nine), usually with contorted, valvate or convolute (sometimes imbricate or open) aestivation, sometimes clawed, usually free (rarely connate at base; sometimes absent). Nectaries often as groups of glandular hairs, usually adaxial on sepal bases, or absent. Disc extrastaminal to intrastaminal, annular, or absent.

Androecium Stamens usually (secondarily) numerous (rarely five, 5+5 or up to more than 1.000), usually in five alternisepalous or antesepalous fascicles (rarely in several whorls), centrifugally developing. Filaments simple or branched, free or connate at base in groups, or connate in two whorls into tube, outer usually antepetalous, usually with fertile stamens, inner usually consisting of staminodia; filaments free from or adnate to petal bases. Anthers basifixed or dorsifixed, versatile or non-versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (sometimes di-, hexa-, or polysporangiate; sometimes septate), usually introrse (sometimes extrorse or latrorse), usually longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits; rarely poricidal, dehiscing by apical or lateral pores or short slits). Tapetum usually secretory (rarely amoeboid-periplasmodial). Antesepalous extrastaminal staminodia often present, usually adnate to fertile stamens.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains 3(–4)-colpate, (2–)3(–9)-colpor(oid)ate, 3(–9)-porate, spiraperturate or polypantoporate, usually shed as monads (rarely tetrads), usually bicellular (sometimes tricellular) at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate (rarely intectate), with columellate or acolumellate infratectum, perforate, microperforate, reticulate, microreticulate, striate, rugulate, foveolate, verrucate, spinulate, psilate or smooth. Pollen grains often germinating with several pollen tubes.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (one to) five (to numerous) usually connate (rarely free, secondarily apocarpous) and usually antepetalous (sometimes antesepalous) carpels; when three carpels, then median carpel abaxial or adaxial. Ovary usually superior (rarely semi-inferior), (unilocular to) quinquelocular (to multilocular), sometimes on gynophore or androgynophore. Style single, simple, or stylodia (two to) five (to numerous), free or more or less connate in lower part. Stigma capitate or lobate, or stigmas capitate or punctate, papillate or non-papillate, usually Dry (rarely Wet) type. Pistillodium?

Ovules Placentation usually axile (sometimes parietal, apical, basal, lateral or free central). Ovules two or several (sometimes numerous; rarely one) per carpel, anatropous or hemianatropous to campylotropous (sometimes orthotropous), ascending, horizontal or pendulous, epitropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar (rarely pseudocrassinucellar). Micropyle usually bistomal (sometimes exostomal or endostomal). Funicular, placental or stylar obturator sometimes present. Archespore sometimes multicellular. Nucellar cap sometimes present. Megagametophyte usually monosporous, Polygonum type. Synergids sometimes with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells often long persistent, sometimes proliferating (up to c. 20 cells). Endosperm development usually nuclear. Endosperm haustorium chalazal. Embryogenesis usually asterad (sometimes caryophyllad or solanad, rarely onagrad or irregular).

Fruit Usually a loculicidal (sometimes septicidal, rarely denticidal or poricidal) capsule, often a schizocarp, regma, with few to numerous usually nutlike (rarely samaroid, baccate, drupaceous or follicular) mericarps (rarely a berry, drupe, nut, nutlet or multifolliculus). Endocarp or centre of fruit sometimes hairy or fleshy.

Seeds Aril or strophiole sometimes present. Seed coat exotegmic or endotestal-exotegmic. Exotesta sometimes wooly or winged. Endotestal cells often with calciumoxalate crystals. Exotegmen usually palisade, often consisting of malpighiacean cells with thickened lignified walls. Exotegmen sometimes with palisade layer invaginating chalazal region, into which hypostase plug, with core and annulus, fits (outer hypostase forming core, ’bixoid chalazal region’). Endotegmic cell walls sometimes thickened. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm usually copious, oily or starchy (sometimes sparse or absent). Embryo straight or curved, usually with chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, often thin. Radicula often short. Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology x = 5–11(–13)

DNA Plastid gene infA lost/defunct. Mitochondrial intron coxII.i3 lost.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin, herbacetin, gossypetin, hibiscetin, etc.) and their glycosides, flavones, afzelechin, flavonoid sulfates, biflavonoids, cyanidin, delphinidin, apigenin, monoterpenes (e.g. borneol), triterpenes, (e.g. dryobalanone), toxic diterpene esters (e.g. phorbol ester diterpenes), oleanolic acid derivatives, dammaranes, dammarane triterpenoids (dipterocarpol), cucurbitacins, arjunolic acid derivatives, quinoid and/or phenolic sesquiterpenes (gossypol, ishwarane etc.), sesquiterpene lactones, ellagic acid, methylated ellagic and gallic acids, hydrolyzable and non-hydrolyzable tannins, proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins), caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, indole alkaloids (e.g. theophylline, caffeine and theobromine), saponins, cyanogenic glycosides and other cyanogenic compounds, naphthoquinones, anthraquinones, polyacetate-derived arthroquinones, acetophenones, coumarins (daphnin, daphnetin), quebrachitol, lignans (syringaresinol, pinoresinol), pinitol, chelidonic acid, ferulic acid, sinapic acid, lipids of cyclopropane and cyclopropenoid fatty acids (sterculiic acid, malvic acid, etc.) and their derivatives, and sterols present. Mucilage as heteropolysaccharides of galacturonic and glucuronic acids with galactose, rhamnose, glucose, and arabinose.

Systematics Malvales are sister-group to Capparales.

Neuradaceae are sister to the remaining Malvales and Thymelaeaceae successive sister to the rest.

The clade [Thymelaeaceae+[Sphaerosepalaceae+[Bixaceae+Cochlospermaceae]+[Cistaceae+ [Sarcolaenaceae+Dipterocarpaceae]]+[Muntingiaceae+Cytinaceae]+Malvaceae]] is characterized by the following potential synapomorphies, according to Stevens (2001 onwards): presence of vestured pits; stratified phloem; cuneate (wedge-shaped) phloem rays; and much thickened and lignified palisade exotegmen.

The clade [Sphaerosepalaceae+[Bixaceae+Cochlospermaceae]+[Cistaceae+[Sarcolaenaceae+ Dipterocarpaceae]]+[Muntingiaceae+Cytinaceae]+Malvaceae] has the potential synapomorphies: hairs often stellate; stipules often well developed; stamens numerous, developing centrifugally, with five or ten (or 15) vascular bundles (when five, then often antepetalous); ovules six or more per carpel; and micropyle bistomal.

The clade [[Bixaceae+Cochlospermaceae]+[Cistaceae+[Sarcolaenaceae+Dipterocarpaceae]]] has the following characteristics in common (Stevens 2001 onwards): presence of secretory ducts; sepals with imbricate aestivation; unique differentiation of ovule chalazal part: plug of hypostase tissue fitting into curved dome-shaped structure formed by exotegmic palisade layer, plug containing core and annulus (bixoid chalaza; Nandi 1998). The unique bixoid chalazal plug forms an opening through the often very hard seed coat of these plants; hence, water may enter the seed and facilitate germination.

Bixaceae, Cochlospermaceae and Cistaceae share: foliar teeth with one vein proceeding into transparent caducous tooth apex; and elongate embryo with thin curved or plicate cotyledons and short stout radicula. However, molecular data recover Cistaceae as sister to [Dipterocarpaceae+Sarcolaenaceae] or at least as member of the trichotomy [Cistaceae+Sarco-laenaceae+Dipterocarpaceae].

Bixaceae and Cochlospermaceae share the characters (Stevens 2001 onwards): secretory ducts present; resiniferous cells present outside veins; hairs glandular, not tufted or stellate; leaf margin serrate; terminal inflorescence; large flowers; sepals with imbricate aestivation; anthers poricidal; stigma slightly lobate to capitate; ovules numerous per carpel; long funicle; micropyle Z-shaped (zig-zag); outer hypostase forming core.

The clade [Cistaceae+[Sarcolaenaceae+Dipterocarpaceae]] has the following potential synapomorphies (Stevens 2001 onwards): ectomycorrhizae present; presence of tracheids; presence of secretory canals; sepals with imbricate quincuncial aestivation; two outer sepals often different from remaining sepals; filaments not articulated; ovules both anatropous and orthotropous; exotegmen curved inwards in chalazal region; hypostase plug with core and annulus; endosperm starchy; and presence of ellagic acid.

Shape of indumentum, hollow style, morphology of stigma, number of carpels, and several other features unite Cistaceae and Sarcolaenaceae. In both Fumana (Cistaceae) and Dipterocarpoideae (Dipterocarpaceae) the outer integument is prolonged and ectomycorrhiza is frequent.

Sarcolaenaceae and Dipterocarpaceae share the characters: usually well developed stipules and complex petiolar anatomy.

Muntingiaceae and Cytinaceae both have many-seeded berry and ellagitannins.

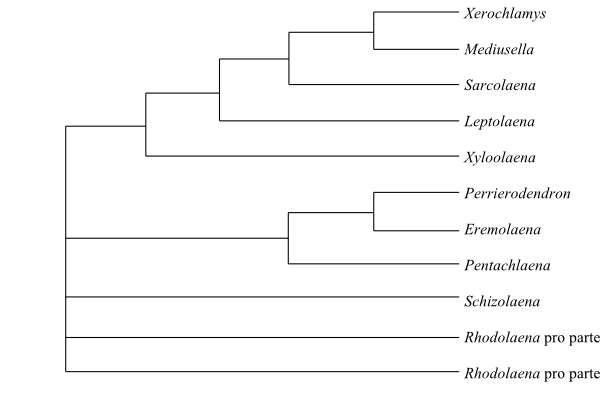

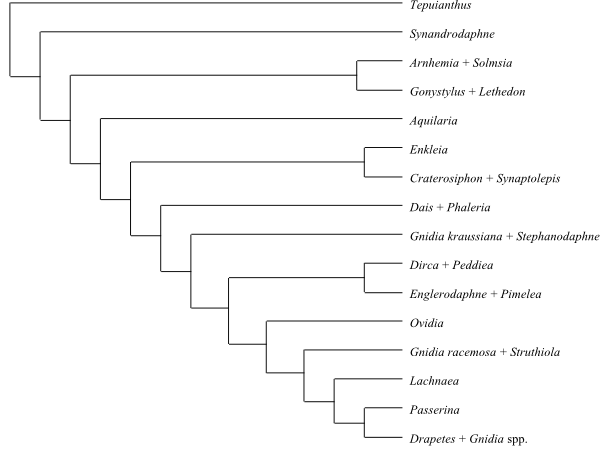

|

Cladogram of Malvales based on DNA sequence data (Stevens 2001 onwards, May 2012 version). |

BIXACEAE Kunth |

( Back to Malvales ) |

Bixales Link, Handbuch 2: 371. 4-11 Jul 1829 [’Bixinae’]; Diegodendraceae Capuron in Adansonia, sér. 2, 3: 392. Oct-Dec 1964

Genera/species 2/6

Distribution Tropical South America, Madagascar.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, evergreen shrubs or small trees. Leaves in Diegodendron fragrant (like camphor). Juice coloured (orange to red).

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio superficial. Vessel elements with simple perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, bordered pits. Vestured pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids or libriform fibres with bordered (Bixa) or simple (Diegodendron) pits, non-septate (radial tracheids present in Bixa arborea). Wood rays in Bixa uniseriate, homocellular; in Diegodendron biseriate, homocellular. Axial parenchyma in Bixa apotracheal diffuse; in Diegodendron apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates. Wood elements storied (Bixa). Secondary phloem stratified into hard fibrous and soft parenchymatous layers. Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes 3:?, trilacunar with ? leaf traces (Bixa), with extrafloral nectariferous glands. Mucilage cells? Medullary parenchyma with secretory canals (with bixine?). Exudate in Bixa red to orange. Idioblasts with calciumoxalate raphides.

Trichomes Hairs in Bixa multicellular, stellate or peltate-lepidote, reddish-brown; glandular hairs peltate.

Leaves Alternate (in Bixa spiral; in Diegodendron distichous), simple or palmately compound, entire or palmately lobed, with conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules in Bixa enclosing bud, in Diegodendron intrapetiolar, unequal in size, sheathing and surrounding stem/branch, caducous; leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection annular; petiole with medullary bundles. Lamina in Bixa densely beset with reddish-brown hairs, in Diegodendron densely gland-dotted, glabrous. Venation in Bixa palmate, brochido-actinodromous, in Diegodendron pinnate. Stomata anomocytic, paracytic or anisocytic (in Diegodendron sometimes cyclocytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids? Parenchyma with schizogenous secretory canals. Resinous secretory cells present outside veins. Hairs stellate or peltate and brown (Bixa), or absent (Diegodendron). Leaf margin serrate or entire. Leaf teeth with one vein running into transparent caducous tooth apex.

Inflorescence Terminal, thyrsoid (in Diegodendron usually panicle), or flowers solitary.

Flowers Usually actinomorphic (in Bixa rarely somewhat zygomorphic), large. Pedicel in Bixa with five large extrafloral nectariferous glands. Hypogyny. Sepals five (or six), with imbricate quincuncial or contorted? (Bixa) aestivation, caducous (Bixa) or persistent (Diegodendron), in Bixa with distinct abaxial glands at base, outer sepals in Diegodendron smaller, free. Petals five (or six), usually with imbricate (in Diegodendron rarely contorted) aestivation, caducous (Diegodendron), free. Nectary absent. Disc in Bixa absent, in Diegodendron indistinct or absent.

Androecium Stamens numerous (in Diegodendron sometimes more than 400), centrifugally developing. Filaments filiform (Diegodendron), free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed (Diegodendron), in Bixa hippocrepomorphic and horizontally folded, non-versatile (Diegodendron), tetrasporangiate, latrorse (Diegodendron), in Bixa poricidal (dehiscing by short lateral, seemingly apical, slits or pores), in Diegodendron longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective in Bixa curved into loop. Tapetum secretory. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains tricolporate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, rugulate, microperforate (Bixa) or verrucate to insulate (Diegodendron).

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (one or) two (to four) more or less connate antesepalous, alternipetalous carpels. Ovary superior, unilocular in Bixa (carpels connate), in Diegodendron usually bilocular (sometimes uni-, tri- or quadrilocular); carpels free below (apocarpy). Style single, simple, in Diegodendron gynobasic, persistent, in Bixa apical. Stigma capitate or somewhat lobate (in Diegodendron punctate), type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation parietal (Bixa) or basal (Diegodendron). Ovules usually two (Diegodendron) or numerous (Bixa) per carpel, anatropous, ascending and epitropous (Diegodendron), bitegmic, pseudocrassinucellar (Bixa) or crassinucellar (Diegodendron). Funicle long (Bixa). Micropyle exostomal to bistomal, somewhat Z-shaped (zig-zag; Bixa). Outer integument ? cell layers thin. Inner integument in Bixa four or five cell layers thick, in Diegodendron ? cell layers thick. Hypostase present (Bixa). Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis irregular (Bixa).

Fruit A loculicidal capsule, usually with long prickles, dehiscing by two valves or remaining indehiscent (Bixa), or a schizocarp with glands and one (to four) indehiscent mericarps (Diegodendron).

Seeds Funicular aril present in Bixa (absent in Diegodendron). Testa in Bixa with red sarcotesta (with bixine, a carotenoid), in Diegodendron thin with viscid outer layer. Exotegmen in Bixa with palisade layer (absent in Diegodendron) invaginating chalazal region, into which hypostase plug, with core and annulus, fits (outer hypostase forming core, ’bixoid chalazal region’). Endotegmic cell walls in Bixa more or less thickened. Hypodermal layer consisting of clepsydromorphous (hour-glass-shaped) cells. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm starchy (Bixa) or absent (Diegodendron). Embryo long, straight, without chlorophyll (Bixa). Cotyledons two, in Bixa spatulate, thin, curved or folded, in Diegodendron thick. Radicula short, stout. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 7 (Bixa)

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavones, flavonoid sulphates, cyanidin, arjunolic acid derivatives, sesquiterpenes (e.g. ishwarane), ellagic acid, tannins, and proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins) present (in Bixa). Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), alkaloids, saponins, and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Dyeing substances (bixine for staining of margarine and other food stuffs, cosmetics; Bixa orellana: annatto, arnotto, roucou).

Systematics Bixa (5; B. arborea, B. excelsa, B. orellana, B. platycarpa, B. urucurana; Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America), Diegodendron (1; D. humbertii; Madagascar).

Bixaceae are sister to Cochlospermaceae or, possibly, to Sphaerosepalaceae (Johnson-Fulton & Watson 2017).

CISTACEAE Juss. |

( Back to Malvales ) |

Cistales DC. ex Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 220. Jan-Apr 1820 [’Cisti’]; Cistopsida Bartl., Ord. Nat. Plant.: 221, 277. Sep 1830 [’Cistiflorae’]; Helianthemaceae G. Mey., Chloris Han.: 9, 185. Jul-Aug 1836 [’Helianthemeae’]; Cistineae Rchb., Deutsch. Bot. Herb.-Buch: lxxvi. Jul 1841

Genera/species 8/205–210

Distribution Temperate and subtropical regions on the Northern Hemisphere east to Central Asia, with their largest diversity in the Mediterranean area, eastern North Africa and the eastern United States; few species in the West Indies and southern South America.

Fossils Uncertain. Fossil fruits and wood assigned to Cistaceae from the Late Eocene have been reported from European strata.

Habit Bisexual, evergreen shrubs or suffrutices, or annual herbs. Numerous species are xerophytes.

Vegetative anatomy Root hairs (rhizoids) absent at least in seedlings. Ectomycorrhiza present in at least Fumana and Helianthemum; endomycorrhiza at least sometimes present. Phellogen ab initio usually superficial (rarely deeply seated). Endodermis sometimes prominent. Vessel elements with simple perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, bordered pits. Vestured pits present. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids or tracheids with bordered pits, non-septate. Wood rays usually uniseriate (sometimes multiseriate, in Pakaraimaea biseriate), heterocellular. Axial parenchyma poorly developed (apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, paratracheal scanty vasicentric) or absent. Wood elements not storied. Phloem not stratified. Intraxylary phloem present in Pakaraimaea. Sieve tube plastids Ss type. Nodes 1:1, unilacunar with one leaf trace. Secretory canals? Heartwood vessels with gum-like substances. Mucilage cells absent? Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals (sometimes druses) present or absent.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate or multiseriate, simple, fasciculate or stellate or peltate (characteristic, seemingly bicellular, each cell with basal inner compartment); peltate-lepidote glandular hairs sometimes present (in Cistus with resinous balsam and ethereal oils).

Leaves Usually opposite (sometimes verticillate, rarely spiral), simple, entire, often coriaceous, sometimes scale-like or ericoid, with conduplicate to curved ptyxis. Stipules probably absent (or intrapetiolar?); leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate. Leaf bases sometimes connate. Venation pinnate or palmate (lamina often single-veined or with at least three parallel veins). Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids usually absent (sometimes as platelets or annular rodlets). Epidermis with or without mucilaginous idioblasts. Cystoliths often present. Leaf margin serrate or entire.

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, cymes of various shape, or flowers solitary.

Flowers Actinomorphic. Receptacle often prolonged into androphore or gynophore? Hypogyny. Sepals (three or) five, with imbricate quincuncial (inner sepals sometimes with contorted) aestivation, when five then two outer much smaller than three inner sepals, usually persistent, free or more or less connate. Petals usually five (in Lechea three small), with usually contorted aestivation (in opposite direction to sepals; in Lechea and Pakaraimaea imbricate quincuncial aestivation), wrinkled in bud, caducous, free (rarely absent); petal epidermis with approx. ten micropapillae per cell. Androgynophore present in Pakaraimaea. Nectary usually absent (annular nectariferous disc rarely present?). Disc extrastaminal to intrastaminal, annular.

Androecium Stamens (three to) numerous (androecium with ten vascular bundles), centrifugally developing, often sensitive. Filaments free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile (basifixed-versatile in Pakaraimaea), tetrasporangiate, introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by usually longitudinal slits); anthers in some cleistogamous flowers adnate to stigma and apically dehiscing. Tapetum secretory. Staminodia usually absent (in Fumana extrastaminal staminodia present).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains (2–)3(–5)-colpor(oid)ate, often starchy, usually shed as monads (rarely tetrads), bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, reticulate, microreticulate, rugulate, striate or striate-reticulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (two or) three to five (to twelve) connate carpels; carpels alternisepalous antepetalous, or median carpel abaxial. Ovary superior, unilocular or incompletely multilocular due to intruding and often connate parietal placentae. Style single, simple, hollow, or absent. Stigma usually one (stigmas rarely three), large, capitate or discoid, often lobate (rarely fringed), papillate (with multicellular multiseriate papillae), Dry type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation parietal (often deeply intrusive). Ovules two to numerous (rarely one) per carpel, usually orthotropous (in Fumana anatropous or hemianatropous), ascending, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Funicle usually long (in Fumana short). Micropyle usually bistomal (in Fumana exostomal). Outer integument approx. two cell layers thick. Inner integument two to four cell layers thick. Parietal tissue approx. two cell layers thick. Nucellar cap approx. two cell layers thick. Hypostase present. Archespore sometimes multicellular. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Synergids with a filiform apparatus. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis solanad.

Fruit Usually loculicidal (septifragal?) capsule (in Pakaraimaea many-seeded nut), often surrounded by persistent sepals.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa thin, starchy, as wet sometimes gelatinous and mucilaginous. Tegmen very hard. Exotegmen palisade, with lignified malphighiacean cells; exotegmen invaginating chalazal region, into which hypostase plug, with core and annulus, fits (outer hypostase forming core, ’bixoid chalazal region’). Endotegmic cells with thickened radial and/or tangential walls. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, starchy. Embryo usually often strongly curved (in Lechea almost straight), long, well developed, with or without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, thin, curved or plicate. Radicula short, stout. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 5, 7, 9–12, 16 (Fumana), 18, 20, 24 – Polyploidy occurring.

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin, etc.), flavonoid sulphates, cyanidin, delphinidin, dammaranes, ellagic and gallic acids, hydrolyzable and condensed tannins, proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins), saponins, acetophenones, and pinitol present. Alkaloids and cyanogenic compounds not found. Certain species of Cistus secrete aromatic balsam (ladanum, labdanum), a mixture of ethereal oils and resin (diterpene and triterpene esters).

Use Ornamental plants, perfumes (Cistus), medicinal plants.

Systematics Pakaraimaeoideae Maguire, P. S. Ashton et de Zeeuw in B. Maguire et P. S. Ashton in Taxon 26: 353. 23 Sep 1977. Pakaraimaea (1; P. dipterocarpacea; the Guayana and Venezuelan Highlands in northern South America). – Cistoideae Eaton, Bot. Dict., ed. 4: 42. Apr–Mai 1836 [‘Cistineae’]. Fumana (15–18; Europe, the Mediterranean, North Africa); Lechea (17–18; North America, Mexico, Belize, Cuba); Crocanthemum (21; southern Canada, United States, Mexico, Central America, Hispaniola, South America), Helianthemum (c 110; Europe, the Canary Islands, the Mediterranean, North Africa to Central Asia), Tuberaria (c 12; West and Central Europe, the Mediterranean), Halimium (12; the Mediterranean, North Africa, Turkey), Cistus (19–20; the Canary Islands, the Mediterranean, Turkey, the Caucasus).

Cistaceae are possibly sister-group to [Dipterocarpaceae+Sarcolaenaceae].

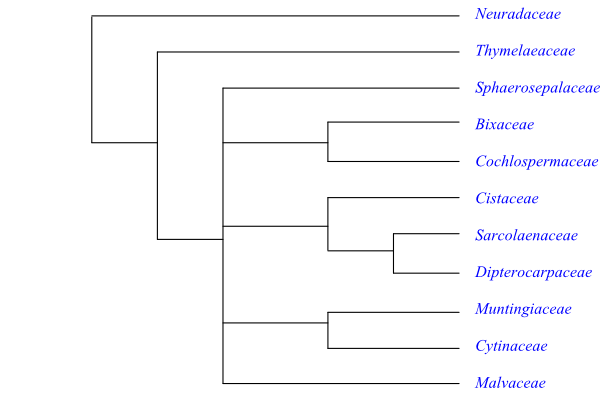

Fumana (with several plesiomorphies) is sister to all other Cistaceae except Pakaraimaea, and Lechea successive sister-group to the remainder.

Pakaraimaea dipterocarpacea. Evergreen tree or shrub. Ectomycorrhiza present. Wood rays usually biseriate. Intraxylary phloem present. Hairs fasciculate. Stipules elongate, caducous. Petiole non-geniculate. Inflorescence panicle. Hypogyny. Petals with imbricate aestivation, shorter than sepals. Stamens c. 40 to c. 50, on short androgynophore. Anthers basifixed-versatile. Pollen grains tricolporate. Exine semitectate, infratectum columellate, reticulate. Pistil composed of five connate carpels. Ovary (quadrilocular or) quinquelocular. Ovules (two to) four per carpel. Fruit a many-seeded nut, probably with five accrescent almost equally sized sepals. Endosperm absent. n = ?

|

Bayesian inference analysis tree of Cistaceae-Cistoideae based on DNA sequence data (Guzmán & Vargas 2009). |

COCHLOSPERMACEAE Planch. |

( Back to Malvales ) |

Cochlospermineae Engl., Syllabus, ed.2: 154. Mai 1898

Genera/species 2/17

Distribution Tropical Africa, India, Sri Lanka, southern Himalayas, northern Burma, northern Thailand, northern Laos, eastern New Guinea, northern Australia, southern United States, Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, deciduous trees or shrubs (Cochlospermum), or perennial herbs with woody subterranean stem (Amoreuxia). Some species are xerophytes. Juice coloured (yellow), resinous.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen? Young stem with vascular tissue forming continuous cylinder. Vessel elements with simple perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, scalariform or opposite, simple or bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids with simple or bordered pits (Amoreuxia without imperforate tracheary elements), non-septate. Wood rays multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse, paratracheal scanty vasicentric, unilateral, or banded. Wood elements often partially storied. Secondary phloem stratified into hard fibrous and soft parenchymatous layers. Sieve tube plastids Pcs type, with protein crystals and starch. Nodes 3:3?, trilacunar with three? leaf traces. Parenchyma in Cochlospermum with branched unicellular resinous idioblasts. Cortex and medulla with mucilage cells and lysigenic mucilage canals. Crystals?

Trichomes Hairs unicellular, simple, or on young shoots multicellular, stalked; sometimes gland-like and peltate-lepidote.

Leaves Alternate (spiral), palmately compound or simple and palmately lobed, with conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules usually small, narrow, caducous; leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundles three, with transection annular; petiole without medullary bundles. Venation palmate. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Epidermis often with mucilage cells. Resinous secretory cells present outside veins. Leaf margin serrate or entire. Leaf teeth with one vein proceeding into transparent caducous apex.

Inflorescence Usually terminal (rarely axillary), thyrsoid, panicle or raceme-like. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) absent.

Flowers Slightly zygomorphic (Amoreuxia, buds in Cochlospermum) or actinomorphic (open flowers in Cochlospermum), large. Hypogyny. Sepals (four or) five, with imbricate or contorted aestivation (sepals unequal in size, or three sepals and two floral prophylls?; median sepal abaxial), caducous, free. Petals (four or) five, with contorted or imbricate aestivation, free. Nectary probably absent. Disc indistinct or absent.

Androecium Stamens numerous, often in two fascicles (Amoreuxia; upper stamens in Amoreuxia much shorter than lower stamens) or in five fascicles (Cochlospermum), centrifugally developing. Filaments free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse, poricidal (dehiscing by one or two apical, sometimes also two basal, pores or pore-like slits). Tapetum secretory. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains tricolpate, tricolporate or tricolporoidate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine intectate to semitectate, with columellate infratectum, reticulate or psilate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of three to five connate carpels; antepetalous or odd carpel adaxial. Ovary superior, unilocular or incompletely trilocular. Style single, simple. Stigma small, entire or somewhat lobate, type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation entirely parietal (when ovary unilocular), or axial at base and apex and parietal in central part (when ovary multilocular). Ovules numerous per carpel, campyloanatropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Funicle long. Micropyle exostomal to bistomal, somewhat Z-shaped (zig-zag). Outer integument three cell layers thick. Inner integument three or four cell layers thick. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A capsule with loculicidal lignified exocarp/mesocarp separating from septicidal membranous endocarp.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa lanate or glabrous, thin. Tegmen thick, hard, with enlarged outer hypodermal cells. Exotegmen invaginating chalazal region, into which hypostase plug, with core and annulus, fits; chalaza closed by hypostase plug (outer hypostase forming core, ’bixoid chalazal region’). Endotegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm thick, oily, without starch. Embryo elongate, usually curved (sometimes straight), chlorophyll? Cotyledons two, spatulate, thin, curved or plicate. Radicula short, stout. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 6, 9, 12, 18 – Polyploidy frequently occurring.

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin, etc.), cyanidin, afzelechin, ellagic acid (Cochlospermum), gum substances (’coutira gum’) with frequently branched acetylated polysaccharides consisting of galactose, rhamnose, glucuronic acid and galacturonic acid (Cochlospermum), and saponins present.

Use Ornamental plants (Cochlospermum), medicinal plants, timber.

Systematics Amoreuxia (4; A. gonzalezii, A. malvifolia, A. palmatifida, A. wrightii; southern Arizona, Mexico, Central America, Colombia, Peru), Cochlospermum (13; western and central tropical Africa, southern and eastern India, Sri Lanka, southern Himalayas, northern Burma, northern Thailand, northern Laos, eastern New Guinea, northern and Western Australia, southern United States, Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America to southeastern Brazil and northern Argentina).

Cochlospermaceae are sister to Bixaceae.

CYTINACEAE Brongn. ex A. Rich. |

( Back to Malvales ) |

Cytinales Dumort., Anal. Fam. Plant.: 13. 1829 [‘Cytinarieae’]

Genera/species 2/13

Distribution The Canary Islands, the Mediterranean, Turkey, southern and western Caucasus, southern Africa, Madagascar, southern Mexico, Central America.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Monoecious or dioecious, achlorophyllous perennial herbaceous endophytic root holoparasites without rhizome or normal roots. Cytinus subgenus Cytinus on species of Cistaceae; Cytinus subgenus Hypolepis on species of at least five different clades of angiosperms; Bdallophytum mostly on Bursera (Burseraceae).

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza absent. Hypha-like cell threads invading host plant and forming endophytic system in roots. Phellogen absent. Secondary lateral growth absent. Xylem elements present in at least Cytinus. Vessels absent. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements? Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Phloem elements present in at least Cytinus. Sieve tube plastids S0 type, without starch or protein inclusions. Nodes? Crystals?

Trichomes Indumentum absent on vegetative parts.

Leaves Alternate (spiral), reduced, scale-like. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Venation? Stomata poorly differentiated (Cytinus). Cuticular waxes absent? Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal, in Bdallophytum spicate, in Cytinus raceme-like or sometimes capitular. Flowers and inflorescence branches pressing themselves outwards through host cortex.

Flowers Actinomorphic. Epigyny. Tepals four to six (Cytinus) or five to nine (Bdallophytum), in one whorl, connate at base; tepals rarely adnate by dissepiment to stamens and stylodium. Thin tissue, diaphragm, present on top of perigonal tube and special outgrowths, ramenta, inserted inside perigonal tube in Cytinus. Nectariferous tissue in Cytinus as hippocrepomorphic glands at adaxial side of perigonal base (absent in Bdallophytum?). Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens six to ten (to more than 20), whorled. Filaments absent. Anthers connate into synandrium (in Cytinus with nectariferous pits between staminal bases), dorsifixed, non-versatile, disporangiate, monothecal, extrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective thick, usually with terminal and often branched appendage. Tapetum secretory? Female flowers without staminodia.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous? Pollen grains di- to tetraporate or indistinctly di- to tetracolpate, usually shed as monads (in some species of Cytinus as tetrads), bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate to semitectate, with columellate infratectum, perforate or microreticulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of five to eight (to 14) connate carpels. Ovary inferior, ab initio septate, multilocular, later unilocular. Style single, simple, long, enlarged and discoid at apex, with nectariferous cavities near base. Stigma commissural, as annular radiate capitate structure on abaxial edge or lower side of discoid apex of central column, in Cytinus with six to eight lobes, in Bdallophytum discoid, type? Male flowers with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation intrusively parietal, with branched placentae. Ovules five to 14 per ovary, orthotropous, unitegmic or bitegmic (then outer integument higly reduced), tenuinucellar. Micropyle endostomal. Outer integument two or three cell layers thick, poorly developed. Inner integument approx. two cell layers thick. Megasporangial epidermis persistent. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Antipodal cells persistent. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis caryophyllad or solanad?

Fruit A many-seeded berry (Cytinus) or a syncarp with berry-like solitary fruits (Bdallophytum).

Seeds Aril absent. Seeds in Cytinus with rudimentary exotesta. Seed coat exotegmic. Exotesta in Bdallophytum? Endotesta hard. Exotegmic cells thickened around. Endotegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm present. Embryo rudimentary, undifferentiated (few-celled in few tiers), chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar?

Cytology n = 12, 16 (Cytinus hypocistis)

DNA

Phytochemistry Very insufficiently known. Ellagitannins (isoterchebin) present.

Use Unknown.

Systematics Cytinus (8; subgenus Cytinus in the Mediterranean, the Canary Islands, Turkey, southern and western Caucasia; subgenus Hypolepis in southern Africa and Madagascar); Bdallophytum (5; B. americanum, B. andrieuxii, B. bambusarum, B. ceratantherum, B. oxylepis; southern Mexico, Central America)

The position of Cytinaceae in Malvales is not clarified. They sometimes appear as sister to Muntingiaceae, although with fairly weak support (Nickrent 2007). Both Cytinaceae and other Malvales have exotegmic seeds and the perianth morphology in Cytinaceae resembles that in Malvaceae. The position of Bdallophytum is uncertain. It is tentatively placed as sister to Cytinus.

DIPTEROCARPACEAE Blume |

( Back to Malvales ) |

Monotaceae (Gilg) Kosterm. in Taxon 38: 123. 27 Feb 1989

Genera/species 14/530–535

Distribution Tropical Africa, Madagascar, the Seychelles, tropical Asia from Sri Lanka and India to New Guinea, Colombian Amazonas, the Guayana and the Venezuelan Highlands, with their highest diversity in lowland rainforests of West Malesia.

Fossils Fossil wood assigned to Dipterocarpaceae has been found on many places. Woburnia porosa was described from England and is probably of Early Cenozoic age. Other fossil woods possibly attributable to Dipterocarpaceae are Dipterocarpoxylon, Dryobalanoxylon, Grewioxylon and Shoreoxylon from tropical Asia and eastern Africa. Pollen grains of Oligocene age have been recorded from Borneo.

Habit Bisexual, evergreen trees or shrubs. Often with large plank buttresses.

Vegetative anatomy Ectomycorrhiza present. Root hairs (rhizoids) sometimes absent. Phellogen ab initio superficial to outer-cortical. Cortical vascular bundles present or absent. Vessel elements usually with simple (rarely scalariform) perforation plates; lateral pits usually alternate (rarely opposite), simple pits. Vestured pits present. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids with simple and/or bordered pits, non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays in Dipterocarpoideae multiseriate, in Monotoideae usually uniseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or banded, or paratracheal scanty vasicentric, aliform, lozenge-aliform, winged-aliform, confluent, unilateral, or banded. Cambium and wood elements sometimes storied. Tyloses frequent (sometimes crystalliferous). Secondary phloem stratified into hard fibrous and soft parenchymatous layers. Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces, or 5:5, pentalacunar with five traces. Cortex, wood and medulla with branched vertical system of intercellular resinous ducts. Medulla often with secretory mucilage cavities. Silica bodies present in many species. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals often frequent. Styloids, acicular crystals and/or crystal sand present in some species.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate or multiseriate, simple or branched, fasciculate, stellate or peltate; glandular hairs unicellular or multicellular, often peltate-lepidote.

Leaves Alternate (spiral or distichous), simple, entire, coriaceous, usually with conduplicate (in Dipterocarpus and Parashorea conduplicate-plicate) ptyxis. Stipules intrapetiolar, caducous (in Stemonoporus early caducous) or persistent; leaf sheath absent. Petiole usually geniculate. Petiole vascular bundle transection annular; bundle surrounding central vascular tissue (complex, often with siphonostele with medullary bundles?). Stipules and leaf bases rarely with nectariferous glands (extrafloral nectaries). Venation pinnate; secondary veins parallel; tertiary veins usually scalariform. Stomata usually anomocytic or cyclocytic (rarely paracytic), sometimes on adaxial side only. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Domatia present as pits along mid-vein. Mesophyll with or without mucilaginous idioblasts and resinous and mucilage canals. Leaf margin entire or sinuate. Adaxial or abaxial surface of young leaves usually with peltate extrafloral nectaries.

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, usually panicle or raceme-like, often branched and more or less monochasial (flowers rarely solitary).

Flowers Actinomorphic. Usually hypogyny (in Anisoptera half epigyny). Sepals two to five, with imbricate or valvate aestivation, usually persistent and strongly accrescent, usually free (rarely connate at base). Petals five, usually with contorted aestivation, usually free (in many Dipterocarpoideae connate at base). Androgynophore present in Monotoideae. Nectary probably absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens five, 5+5, or 5+5+5 (rarely up to c. 110, irregularly inserted; androecial bundles five, or five alternipetalous and five alternisepalous), centrifugally developing. Filaments flattened or filiform, free or connate below, free from or adnate at base to petals (epipetalous). Anthers basifixed (Dipterocarpoideae) or basifixed-versatile (Monotoideae), usually tetrasporangiate (rarely disporangiate), usually latrorse, longicidal (usually dehiscing by longitudinal slits; rarely poricidal, dehiscing by two apical pores); connectives usually prolonged at apex. Tapetum secretory, with binucleate cells. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tricolpate (in Monotoideae tricolporate), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine semitectate, with columellate infratectum, reticulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (two or) three (to five) connate carpels; median carpel abaxial. Ovary usually superior (rarely semi-inferior), usually trilocular (rarely bilocular, quadrilocular, or quinquelocular). Style single, simple, or stylodia three, free or connate below, often widened at base into stylopodium. Stigmas usually three (stigma rarely single, entire to sexalobate), type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation usually axile or lateral (sometimes apical). Ovules (one or) two (to four) per carpel, usually anatropous (when placenta lateral) or pendulous (when placenta axile), epitropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal or exostomal (Dipterocarpoideae). Outer integument two to ten cell layers thick. Inner integument two to nine cell layers thick, in Dipterocarpus vascularized. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis asterad or irregular.

Fruit Usually a single-seeded nut (in Monotoideae and Upuna a capsule) with one to five wings formed by persistent and strongly (and often non-uniform) accrescent calyx (absent in some representatives).

Seeds Aril usually absent (present in Upuna). Testa vascularized. Exotesta? Endotesta? Exotegmic cells usually palisade, with sclereids; exotegmen invaginating chalazal region, into which hypostase plug, with core and annulus, fits (outer hypostase forming core, ’bixoid chalazal region’)? Endotegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm usually absent (present in Monotoideae and Dipterocarpus). Embryo curved, with chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, often plicate, usually unequal in size, entire or lobed, enclosing radicula, starchy or with lipids. Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = 6, 7, 10–13 (Dipterocarpoideae) – Polyploidy occurring.

DNA Mitochondrial coxI intron present (Shorea).

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), afzelechin, cyanidin, monoterpenes (e.g. borneol in ‘borneo-camphor’), sesquiterpenes and triterpenes (dryobalanone etc.) in balsam, dipterocarpol (hydroxydammaradienone-II, a triterpenoid), oleo-resins, sesquiterpenol-resins, non-methylated and methylated ellagic acids, gallic acid, bergenin (gallic acid derivative) tannins, proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins), ursolic acid, oleanolic acid derivatives, dammaranes, anthraquinones, polyacetate-derived arthroquinones, and stilbenoids (e.g. resveratrol; hydroxylated derivatives of stilbene) present. Alkaloids, saponins, and cyanogenic compounds not found. Aluminium accumulated in some species.

Use Timber (hardwood), resins (dammar), camphor (Dryobalanops aromatica), butter fats from fruits.

Systematics

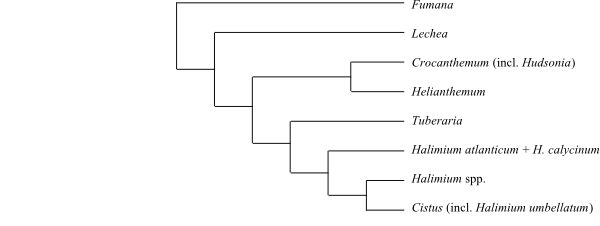

Dipterocarpaceae are sister to Sarcolaenaceae (Heckenhauer & al. 2017).

Monotoideae Thonner, Bl.-pfl. Afr.: 386. Oct 1908

3/c 34. Marquesia (3; M. acuminata, M. excelsa, M. macroura; tropical Africa), Monotes (c 30; tropical Africa, Madagascar), Pseudomonotes (1; P. tropenbosii; Amazonian Colombia). – Tropical Africa, Madagascar, Amazonian Colombia. Ectomycorrhiza? Wood rays usually uniseriate. Leaf base with adaxial gland. Hypogyny. Androgynophore present. Anthers basifixed-versatile. Pollen grains tricolporate. Exine reticulate, with columellate infratectum. Pistil composed of three (to five) connate carpels. Ovules (one or) two per carpel, sometimes orthotropous. Fruit a capsule. Exostome prolonged. Endosperm present, without starch. n = ?

Dipterocarpoideae Burnett, Outlines Bot.: 824, 1094, 1120. Feb 1835 [’Dipterocarpidae’]

11/495–500. Vatica (c 65; tropical Asia), Dipterocarpus (c 70; tropical Asia, with their highest diversity in West Malesia), Dryobalanops (7; D. aromatica, D. beccarii, D. fusca, D. keithii, D. lanceolata, D. oblongifolia, D. rappa; the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Borneo), 'Shorea' (c 300; Sri Lanka, northern India, southern China, Southeast Asia, Malesia to the Moluccas and the Lesser Sunda Islands, with their largest diversity in West Malesia to the Philippines; paraphyletic), Parashorea (14; southern China, Southeast Asia, Malesia; in Shorea?), Anisoptera (10; Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea), Cotylelobium (5; C. burckii, C. lanceolatum, C. lewisianum, C. melanoxylon, C. scabriusculum; Sri Lanka, peninsular Thailand, the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Borneo), Upuna (1; U. borneensis; Borneo), Vateria (4; V. acuminata, V. copallifera, V. indica, V. macrocarpa; southern India, Sri Lanka), Vateriopsis (1; V. seychellarum; the Seychelles), Stemonoporus (c 20; Sri Lanka). – The Seychelles, Sri Lanka, India, Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea, with their largest diversity in West Malesia. Ectomycorrhiza present. Wood rays usually multiseriate. Intercellular resinous canals abundant in wood, vascular tissue and internode pits. At least lateral leaf traces leaving central cylinder well below node, before entering petiole. Usually hypogyny (rarely epigyny). Sepals with valvate or imbricate aestivation. Androgynophore absent. Stamens five antesepalous, ten to c. 110. Anthers basifixed; connectives usually prolonged. Pollen grains tricolpate. Pistil composed of (two or) three connate carpels. Ovary usually superior (rarely semi-inferior). Ovules two (or three) per carpel. Micropyle endostomal. Outer integument two to five (in Dipterocarpus up to ten) cell layers thick. Inner integument two to nine cell layers thick. Fruit usually a single-seeded nut (in Upuna a loculicidal capsule). Endocarp hairy. Sepals persistent, non-uniformly accrescent and thickening. Thin aril present in Upuna. Exotegmen usually palisade. Endosperm usually absent (present in Dipterocarpus, without starch). n = (6–)7, (10–)11(–13).

Neobalanocarpus heimii – here included in Shorea – is sometimes interpreted as a hybrid between species of Shorea and Hopea, the latter being nested in Shorea (together with the sections Anthoshorea and Doona, according to Dayanandan & al. 1999).

|

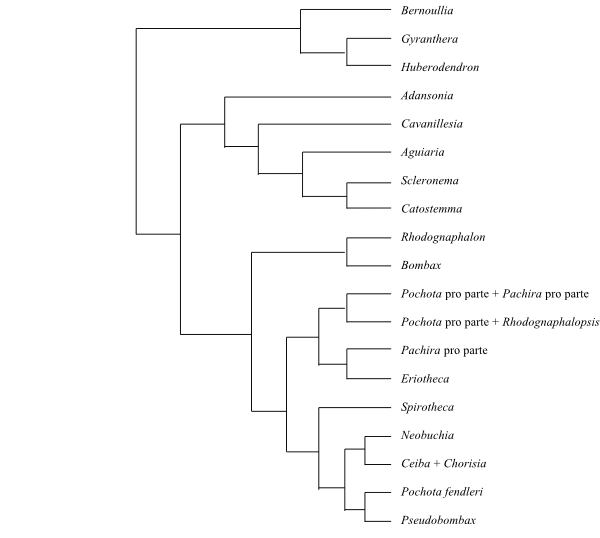

Cladogram of Dipterocarpaceae based on DNA sequence data (Dayanandan & al. 1999). |

MALVACEAE Juss. |

( Back to Malvales ) |

Tiliaceae Juss., Gen. Plant.: 289. 4 Aug 1789, nom. cons.; Sterculiaceae Vent. in R. Salisbury, Parad. Lond. 2: ad t. 69. 1 Mai 1807, nom. cons.; Byttneriaceae R. Br. in M. Flinders, Voy. Terra Austr. 2: 540. 19 Jul 1814 [’Buttneriaceae’], nom. cons.; Malvopsida R. Br. in Tuckey, Narr. Exped. Zaire: 429. 5 Mar 1818 [’Malvaceae’]; Fugosiaceae Martinov, Tekhno-Bot. Slovar: 273. 3 Aug 1820 [‘Fugosiae’], nom. illeg.; Hermanniaceae Marquis, Esq. Règne Vég.: 52. 15-22 Jul 1820 [‘Hermannieae’]; Pentapetaceae Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 222. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Pentapeticae’]; Sidaceae Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 222. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Sideae’]; Sterculiales Vent. ex Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 222. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Sterculiae’]; Tiliales Juss. ex Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 222. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Tiliaceae’]; Bombacaceae Kunth, Malvac., Büttner., Tiliac.: 5. 20 Apr 1822 [’Bombaceae’], nom. cons.; Lasiopetalaceae Reichb. in Mag. Aesth. Bot.: ad t. 37. 1823 [’Lasiopetaleae’]; Byttneriales Link, Handbuch 2: 350. 4-11 Jul 1829 [’Buettneriaceae’]; Dombeyaceae Kunth in Desfontaines, Tabl. École Bot., ed. 3: 252. 15-21 Mar 1829 [’Dombeyeae’], nom. cons. prop.; Triplobaceae Raf., Sylva Tellur.: 110. Oct-Dec 1838 [’Triplobides’], nom. illeg.; Malvineae Rchb. Deutsch. Bot. Herb.-Buch: lxxxi. Jul 1841; Tiliineae Rchb., Detusch. Bot. Herb.-Buch: lxxxv. Jul 1841; Philippodendraceae (Endl.) A. Juss. in V. V. D. d’Orbigny, Dict. Univ. Hist. Nat. 9: 735. 1847 [’Philippodendreae’]; Fremontiaceae J. Agardh, Theoria Syst. Plant.: 264. Apr-Sep 1858 [‘Fremontieae’], nom. illeg.; Helicteraceae J. Agardh, Theoria Syst. Plant.: 264. Apr-Sep 1858 [’Helictereae’]; Hibiscaceae J. Agardh, Theoria Syst. Plant.: 275. Apr-Sep 1858 [’Hibisceae’]; Melochiaceae J. Agardh, Theoria Syst. Plant.: 271. Apr-Sep 1858 [’Melochieae’]; Plagianthaceae J. Agardh, Theoria Syst. Plant.: 201. Apr-Sep 1858 [’Plagiantheae’]; Sparmanniaceae J. Agardh, Theoria Syst. Plant.: 260. Apr-Sep 1858; Theobromataceae J. Agardh, Theoria Syst. Plant.: 264. Apr-Sep 1858 [‘Theobromeae’]; Chiranthodendraceae A. Gray in Proc. Amer. Acad. Arts 22: 303. 4 Mar 1887 [’Cheiranthodendreae’]; Cacaoaceae Augier ex T. Post et Kuntze, Lex. Gen. Phan.: 667, 710. 20-30 Nov 1903, nom. illeg.; Berryaceae Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.: xxxvii. 23 Dec 2001; Grewiaceae (Dippel) Doweld et Reveal in Reveal in Bot. Rev. (Lancaster) 71: 100. 20 Mai 2005; Durionaceae Cheek, Kew Bull. 61: 443. 8 Dec 2006

Genera/species 242/4.355–4.875

Distribution Cosmopolitan except polar areas, with their largest diversity in tropical forests.

Fossils From Paleocene and younger strata, pollen grains and macrofossils (mainly wood) of Grewioideae, Sterculioideae, Malvoideae, and perhaps Dobeyoideae are known. Fossils attributed to Byttnerioideae have been found in the Miocene of Mexico and the Čech Republic. Fossil pollen grains and wood of Bombacoideae are known from Paleocene layers in South America and Africa, and from younger strata in Asia, Antarctica, Australia, and New Zealand. Fossil pollen grains of Helicteroideae have been found in Cenozoic layers in Europe and Asia and Tilia is known from numerous Cenozoic fossils. Craigia – with extant occurrences only in China – was, according to records from the Eocene onwards, distributed in North America, Europe, Spitsbergen and Asia during the Cenozoic.

Habit Usually bisexual (rarely monoecious, polygamomonoecious or dioecious), evergreen or deciduous trees, shrubs or suffrutices (rarely lianas), perennial, biennial or annual herbs. Some species are xerophytes. Some genera with tough fibres in bark and stem.

Vegetative anatomy Roots often with phloem fibres. Phellogen ab initio epidermal or outer cortical. Vessel elements usually with simple perforation plates; lateral pits usually alternate (rarely scalariform), simple and/or bordered pits. Vestured pits sometimes present? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements usually fibre tracheids or (sometimes very long) libriform fibres (sometimes tracheids) with simple pits, usually non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, usually heterocellular, usually dilated. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal aliform, lozenge-aliform, winged-aliform, confluent (in concentric bands), reticulate, vasicentric, or banded (rarely scanty or scalariform). Wood elements often storied. Wood often fluorescent. Tyloses sometimes frequent (sometimes crystalliferous). Several types of tile cells (almost unique to Malvaceae) present in many species. Secondary phloem in young stems and branches often tangentially stratified into hard fibrous and soft (non-fibrous) parenchymatous layers. Phloem rays cuneate, dilated. Sieve tube plastids S type; sieve tubes with non-dispersive protein bodies. Nodes usually 3:3?, trilacunar with three? leaf traces (rarely penta- or multilacunar with five or more? traces). Lysigenic or schizogenic mucilaginous canals, cavities and cells often present (especially in epidermis, cortex and medulla). Heartwood sometimes with gum-like deposits. Silica bodies present in some species. Cortex with or without cristarque cells. Calciumoxalate crystals (usually in groups) sometimes as druses, styloids, crystal sand or acicular crystals. Prismatic crystals abundant, especially in some wood ray and axial parenchyma cells.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, simple or branched, fasciculate (as hair tufts), multi-armed, stellate, peltate, lepidote; glandular hairs often frequent (also peltate; rarely prickles).

Leaves Usually alternate (spiral or distichous, rarely opposite), simple or palmately compound (rarely unifoliolate), entire or palmately lobed, usually with conduplicate(-plicate) ptyxis. Stipules usually well developed, sometimes large and foliaceous, often early caducous (rarely reduced); leaf sheath absent. Petiole usually pulvinate proximally and distally. Petiole vascular bundle transection usually arcuate or annular; petiole sometimes also with inner cylinder of bundles. Adaxial hypodermis sometimes present. Venation usually palmate (sometimes pinnate); one vein proceeding into non-glandular tooth apex. Stomata usually anomocytic (rarely paracytic, tetracytic, or helicocytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids as rosettes of rodlets, chemically characterized by presence of special triterpenoids, or sometimes as membranous crystalloids often with filiform extensions. Domatia as pockets or hair tufts (rarely pits) or absent. Epidermis and mesophyll with or without mucilaginous idioblasts. Mesophyll with or without sclerenchymatous idioblasts. Leaf margin serrate (often with malvoid teeth; sometimes glandular-serrate), crenate or entire. Stipules, petiole and abaxial side of lamina often with extrafloral nectaries.

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, cymose of various shape, or flowers solitary (in Sterculioideae panicle; in Tilioideae sometimes supra-axillary: floral or cymular bract simultaneously subtending vegetative bud). Inflorescence usually composed of cymose, often modified, ’bicolor units’, consisting of one terminal flower with three bracts, two of which usually subtending one cymose partial inflorescence each, with normal number of floral prophylls (bracteoles), and lowermost bract not subtending any partial inflorescence. Extrafloral nectaries sometimes present on bracts or pedicels.

Flowers Usually actinomorphic (rarely zygomorphic or asymmetrical), often large. Epicalyx (present in some genera) usually consisting of three (rarely more than three) bracts and together with remaining floral parts probably representing reduced ‘bicolor unit’. Receptacle often elongated into androgynophore, androphore or gynophore. Hypogyny (rarely epigyny?). Sepals (three to) five, usually with valvate (sometimes imbricate) aestivation, persistent or caducous, sometimes petaloid, free or more or less connate in lower part. Petals (three to) five, usually with contorted or valvate (sometimes imbricate or open?) aestivation, sometimes clawed, usually free (rarely connate at base; sometimes absent). Nectaries usually as groups of densely packed multicellular glandular hairs, usually adaxial on sepal bases (rarely on petals or androgynophore). Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens usually numerous (in Adansonia up to more than 1.000; rarely five or 5+5), usually in five alternisepalous or antesepalous fascicles, fundamentally obdiplostemonous, centrifugally developing. Filaments often branched, free or connate at base in fascicles or connate usually in two whorls into tube, outer whorl usually antepetalous, usually with fertile stamens, inner whorl usually staminodial; filaments free from or adnate to petal bases (epipetalous). Anthers basifixed or dorsifixed, often versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (sometimes di-, hexa-, or polysporangiate; sometimes septate), introrse or extrorse, usually longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits; rarely poricidal, dehiscing by apical pores or short slits); connective sometimes slightly prolonged at apex. Tapetum usually secretory (rarely amoeboid-periplasmodial). Usually antesepalous and extrastaminal staminodia often present, usually adnate to fertile stamens.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains 3(–4)-colpate, 3(–9)-colporate, 3(–9)-porate, spiraperturate or polypantoporate, usually shed as monads (rarely tetrads), usually bicellular (rarely tricellular) at dispersal. Mature pollen grains sometimes starchy. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate or acolumellate infratectum, perforate to reticulate, rugulate, verrucate, spinulate, covered with spines, or smooth. Pollen grains at germination often with several pollen tubes.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (two to) five (to numerous) usually connate (sometimes secondarily free, apocarpous) and usually antepetalous (sometimes antesepalous) carpels; when three carpels, then median carpel abaxial or adaxial; carpels sometimes (in Sterculioideae) opening as seed develops. Ovary superior, (unilocular to) quinquelocular (to multilocular; locules in Malopeae horizontally divided by secondary septa), stipitate (on gynophore) or on androgynophore. Stylodia (two to) five (to numerous), free or more or less connate in lower part. Stigmas capitate or lobate, papillate or non-papillate, usually Dry (rarely Wet) type (large variation in Malvoideae). Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation usually axile (rarely parietal or free central). Ovules two or several (sometimes numerous; rarely one) per carpel, anatropous or hemitropous to campylotropous (rarely orthotropous), ascending, horizontal or pendulous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle usually bistomal, Z-shaped (zig-zag; sometimes exostomal, rarely endostomal). Outer integument two to eight cell layers thick. Inner integument three to ten (to 15) cell layers thick. Funicular, placental or stylar obturator sometimes present. Hypostase sometimes present. Archespore sometimes multicellular. Parietal tissue two to seven cell layers thick. Nucellar cap sometimes formed (through divisions of epidermal megasporangial cells). Megagametophyte usually monosporous, Polygonum type. Synergids sometimes with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells often long persistent and sometimes proliferating (up to c. 20 cells). Endosperm development usually nuclear. Endosperm haustorium chalazal. Embryogenesis usually asterad (sometimes caryophyllad, rarely onagrad). Polyembryony sometimes occurring. Sporophytic self-incompatibility often present.

Fruit Usually a loculicidal (sometimes septicidal, rarely denticidal or poricidal) capsule, often a schizocarp, regma, with few to numerous usually nutlike (rarely samaroid, baccate, drupaceous or follicular) mericarps (rarely berry, drupe, nutlet or assemblage of follicles), sometimes entirely or partially lignified, coriaceous, carnose or membranous. Endocarp or centre of fruit sometimes hairy or fleshy.

Seeds Aril or strophiole sometimes present. Seed coat usually endotestal-exotegmic. Exotesta sometimes lanate or winged. Endotestal cells with calciumoxalate crystals. Exotegmen palisade, often consisting of malpighiacean cells with lignified walls (in Leptonychia with short fibres). Endotegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm usually copious, oily or starchy (sometimes sparse or absent). Embryo straight or curved, with or without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, thin or fleshy, sometimes folded or inrolled. Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = 7–10 (Grewioideae); n = (5–7) 10(–13) (Byttnerioideae); n = 9, 14, 20, 25 or higher (Helicteroideae); n = 19, 20, 30 or higher (Dombeyoideae); n = 41, c. 80, 82 (Tilioideae); n = 10, 20 (Brownlowioideae); n = (15, 16, 18) 20 (21 or higher) (Sterculioideae); n = (20, 36–)43–46 (up to at least 138) (Bombacoideae); n = 5–28 (to more than 50) (Malvoideae) – Polyploidy occurring.

DNA Plastid gene infA lost (Glycine; present in nuclear genome).

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin, herbacetin, gossypetin, hibiscetin, etc.) and their glycosides, flavones, cyanidin, delphinidin, quinoid and/or phenolic sesquiterpenes (e.g. gossypol), dammaranes, cucurbitacins, ellagic and gallic acids, sesquiterpene lactones, caffeic acid, indole alkaloids (e.g. theophylline, caffeine and theobromine), cyanogenic compounds, p-coumaric acid, naphthoquinones, acetophenones, quebrachitol, lignans (syringaresinol), ferulic acid, sinapic acid, and lipids of cyclopropenoid fatty acids (sterculic acid, malvic acid, etc.) and their derivatives present. Saponins? Iridoids? Mucilage as heteropolysaccharides of galacturonic and glucuronic acids with galactose, rhamnose, glucose, and arabinose.

Use Ornamental plants, textile plants (seed hairs from Gossypium; endocarp hairs, kapok, from Ceiba pentandra, Bombax etc.; phloem fibres from Corchorus capsularis, Abroma augusta, Hibiscus cannabinus, H. sabdariffa, etc.), fruits (aril from Durio zibethinus, etc.), vegetables (Hibiscus esculentus etc.), spices, beverages and stimulants (Theobroma cacao, T. grandiflorum, Cola spp., etc.), medicinal plants (Althaea officinalis etc.), seed oils (Gossypium), timber, carpentries (balsa from Ochroma pyramidale etc.), forage plants (Hermannia spp.).

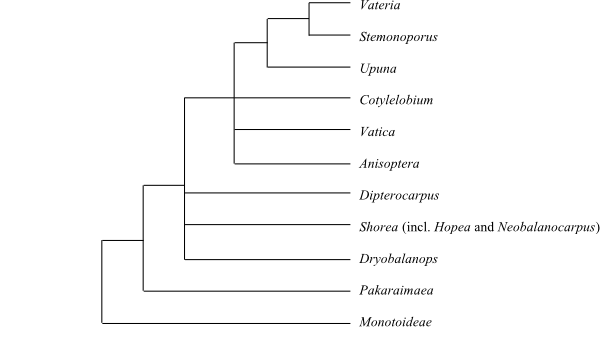

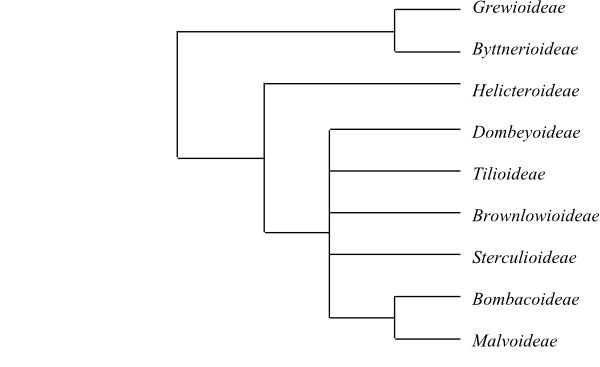

Systematics The sister-group relationships of Malvaceae as well as among their main clades are largely unresolved. Grewioideae and Byttnerioideae (Byttneriina) form a basal clade sister to the remainder (=Malvadendrina), and Helicteroideae may be sister to the rest, yet with fairly low support. Dombeyoideae, Tilioideae, Brownlowioidae, Sterculioideae, and [Bombacoideae+Malvoideae] (Malvatheca) form a polytomy.

[Grewioideae+Byttnerioideae] (Byttneriina)

Grewioideae Dippel, Handb. Laubholzk. 3: 56. Oct-Nov 1893 [‘Grewieae’]

25/680–695. Grewieae Endl., Gen. Plant.: 1006. 1-14 Feb 1840. Luehea (c 25; southern Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America), Lueheopsis (11; tropical South America), Colona (35–40; southern China, Southeast Asia, Malesia), Goethalsia (1; G. meiantha; Central America, Colombia), Desplatsia (5; D. chrysochlamys, D. dewevrei, D. floribunda, D. mildbraedii, D. subericarpa; tropical West and Central Africa), Duboscia (2; D. macrocarpa, D. viridiflora; tropical West and Central Africa), Trichospermum (35–40; Malesia to Solomon Islands, the Santa Cruz Islands, Fiji, Samoa, tropical America), Mollia (17–18; tropical South America), Microcos (13–15; tropical Asia to Fiji), Grewia (c 320; tropical and subtropical regions of the Old World), Eleutherostylis (1; E. renistipulata; the Moluccas, New Guinea), Hydrogaster (1; H. trinervis; eastern Brazil), Tetralix (6; T. brachypetalus, T. cristalensis, T. eriophora, T. jaucoensis, T. moanensis, T. nipensis; Cuba), Vasivaea (2; V. alchorneoides, V. podocarpa; Brazil, Peru). – Apeibeae Benth. in J. Proc. Linn. Soc., Bot. 5(Suppl. 2): 55. 1861. Apeiba (10; tropical South America), Ancistrocarpus (3; A. bequaertii, A. comperei, A. densispinosus; tropical Africa), Sparrmannia (4; S. africana, S. discolor, S. ricinocarpa, S. subpalmata; tropical Africa, Madagascar), Entelea (1; E. arborescens; New Zealand, Three Kings Islands), Clappertonia (3; C. ficifolia, C. minor, C. polyandra; tropical West and Central Africa), Glyphaea (2; G. brevis, G. tomentosa; tropical Africa), Corchorus (75–80; tropical and subtropical regions on both hemispheres), Pseudocorchorus (5; P. alatus, P. cornutus, P. greveanus, P. mamillatus, P. pusillus; Madagascar), Triumfetta (c 100; tropical regions on both hemispheres), Heliocarpus (1; H. americanus; Mexico, Central America), Erinocarpus (1; E. nimmonii; southwestern India). – Tropical and subtropical regions. Sepals free, without nectaries. Petals with various adaxial epidermal modifications (in Grewia and Luehea with nectariferous hairs at base). Androgynophore usually present (in Triumfetta nectariferous). First five stamens antesepalous (sometimes absent), additional stamens centrifugally developing. Filaments usually free. Staminodia absent. Pollen grains prolate. Pistil composed of two to ten connate carpels. Outer integument two or three cell layers thick. Inner integument three to seven cell layers thick. Micropyle exostomal or endostomal. n = 7–9 (10).

|

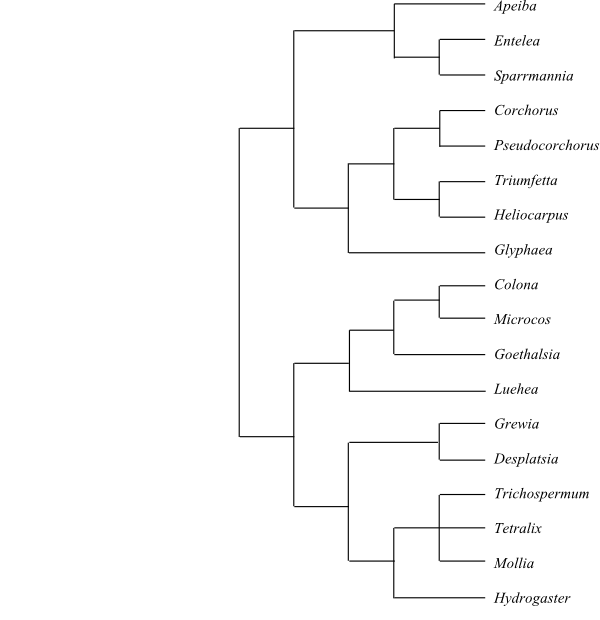

Bayesian majority rule consensus tree of Grewioideae based on DNA sequence data (Brunken & Muellner 2012; Pseudocorchorus added). |

Byttnerioideae Burnett, Outlines Bot.: 821, 1119. Feb 1835 [‘Buttneridae’]

25/700–725. Pantropical. Durio type tile cells present. Leaves alternate (often distichous), usually simple and entire (in Herrania palmately lobed). Petiole vascular bundle transection incurved-arcuate. Sepals usually connate. Petals wide at base (with margins inflexed), later clawed, often spatulate, linear or bilobate (rarely absent). Stamens five (to c. 30), only in antepetalous fascicles. Filaments adnate to petals (epipetalous). Tapetum seemingly amoeboid-periplasmodial (cell content resorbed). Antesepalous petaloid staminodia usually present. Staminal fascicles and staminodia together forming tube. Nectar usually secreted through nectarostomata. Style branched at apex. Parietal placentation present in Leptonychia. Outer integument two to four cell layers thick. Inner integument three to ten cell layers thick. n = (5–7) 10(–13). – The subdivision below follows Whitlock & al. (2001).

|

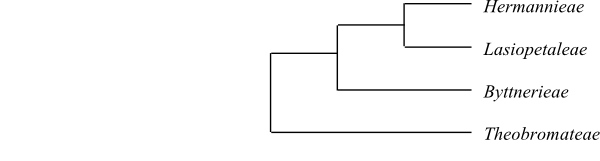

Cladogram (simplified) of Byttnerioideae based on DNA sequence data (Whitlock & al. 2001). |

[Theobromateae+[Byttnerieae+[Lasiopetaleae+Hermannieae]]]

Theobromateae A. Stahl, Estud. Fl. Puerto-Rico 2: 103. 1884 [‘Theobromeae’]

4/43. Guazuma (3; G. crinita, G. longipedicellata, G. ulmifolia; southern Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America), Glossostemon (1; G. bruguieri; the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, Iran), ’Theobroma’ (22; Central America, tropical South America; paraphyletic; incl. Herrania?), Herrania (17; tropical South America; in Theobroma?). – Southwest Asia, tropical America.

[Byttnerieae+[Lasiopetaleae+Hermannieae]]

Byttnerieae DC., Prodr. 1: 484. Jan (med.) 1824 [‘Büttneriaceae verae’]

8/260–265. Scaphopetalum (12; tropical Africa), Leptonychia (c 25; tropical regions in the Old World), Abroma (1; A. augusta; tropical Asia, northeastern Queensland), Kleinhovia (1; K. hospita; tropical Asia, northeastern Queensland), Rayleya (1; R. bahiensis; Bahia in Brazil), ’Byttneria’ (c 140; tropical regions on both hemispheres; paraphyletic; incl. Ayenia?), Ayenia (c 80; southern United States to Argentina; in Byttneria), Megatritheca (2; M. devredii, M. grossedenticulata; Gabon, Congo). – Tropical regions on both hemispheres.

[Lasiopetaleae+Hermannieae]

Lasiopetaleae DC., Prodr. 1: 488. Jan (med.) 1824

9/150–155. Seringia (>20; Madagascar, New Guinea, Australia), Commersonia (c 30; Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea, Australia, New Caledonia), Androcalva (14?; Australia), Maxwellia (1; M. lepidota; New Caledonia), Hannafordia (4; H. bissillii, H. kessellii, H. quadrivalvis, H. shanesii; central Australia), Guichenotia (17; southwestern Western Australia), Lysiosepalum (3; L. abollatum, L. aromaticum, L. rugosum; southwestern Western Australia), Lasiopetalum (30–35; southwestern Western Australia, southeastern Australia, Tasmania), Thomasia (c 30; southwestern Western Australia, southeastern South Australia, Victoria). – Madagascar, New Guinea, Australia, Tasmania, New Caledonia.

Hermannieae DC., Prodr. 1: 490. Jan (med.) 1824

4/250–265. ’Melochia’ (55–60; tropical and subtropical regions on both hemispheres, with their highest diversity in tropical America; non-monophyletic), Hermannia (c 120; tropical and subtropical regions on both hemispheres, with their largest diversity in the Cape Provinces in South Africa), Dicarpidium (1; D. monoicum; northwestern Australia), Waltheria (45–50; tropical Africa, Madagascar, the Malay Peninsula, Taiwan, tropical America). – Tropical and subtropical regions on both hemispheres.

[Helicteroideae+Dombeyoideae+Tilioideae+Brownlowioideae+Sterculioideae+[Bombacoideae+Malvoideae]] (Malvadendrina)

Deletion of 21 bp present in plastid gene ndhF.

Helicteroideae Meisn., Plant. Vasc. Gen.: Tab. Diagn. 29, Comm. 25. 26 Mar-1 Apr 1837 [‘Helictereae’]

12/128–133. Tropical regions, with their highest diversity in Southeast Asia and West Malesia. Durio type tile cells present. Hairs sometimes lepidote. Leaf venation in Durioneae pinnate. Sepals connate. Petals often with lateral constrictions. Androgynophore present. Stamens usually in fascicles and/or forming short tube. Pollen grains columellate or microverrucate to suprareticulate. Outer integument two cell layers thick. Inner integument two cell layers thick. Aril usually absent (sometimes present). Testa sometimes multiplicative. n = 9, 14, 20, 25 or higher. – Helicteroideae may be sister-group to the remaining Malvadendrina (Baum & al. 1998; Alverson & al. 1999).

Helictereae Schott et Endl., Melet. Bot.: 30. 1831

6/75–80. Reevesia (c 15; tropical Asia, Central America), Ungeria (1; U. floribunda; Norfolk Island), Helicteres (55–60; tropical Asia, tropical America), Neoregnellia (1; N. cubensis; Cuba, Hispaniola), Mansonia (2; M. altissima, M. diatomanthera; tropical Africa, Assam, Burma), Triplochiton (2; T. scleroxylon, T. zambesiacus; tropical Africa). – Pantropical.

Durioneae Becc. in Malesia 3: 206. Sep 1889

6/c 53. Neesia (8; West Malesia), Coelostegia (6; C. borneensis, C. chartacea, C. griffithii, C. kostermansii, C. montana, C. neesiocarpa; West Malesia), Kostermansia (1; K. malayana; the Malay Peninsula), Cullenia (2; C. exarillata, C. rosayroana; India, Sri Lanka), Boschia (6; B. acutifolia, B. excelsa, B. grandiflora, B. griffithii, B. mansonii, B. oblongifolia; Burma, Malesia), Durio (c 30; West Malesia). – India, Sri Lanka, Burma, Malesia. Hairs lepidote. Epicalyx ab initio connate. Anthers often multilocular. n = 14.

Dombeyoideae (Lindl.) Beilschm. in Flora 16(Beibl. 7): 86, 106. 14 Jun 1833 [‘Dombeyaceae s. Wallichieae’]

21/370–375. Nesogordonia (c 20; tropical Africa, Madagascar), Pterospermum (25–30?; tropical Asia), Schoutenia (c 10; Thailand to Central Malesia, northern Australia), Sicrea (1; S. godefroyana; Cambodia), Burretiodendron (7; B. brilletii, B. esquirolii, B. hsienmu, B. kydiifolium, B. obconicum, B. siamense, B. yunnanense; southwestern China, Southeast Asia), Melhania (c 45; tropical regions in the Old World), Paramelhania (1; P. decaryana; southeastern Madagascar), Harmsia (1; H. lepidota; northeastern Africa), Astiria (1; A. rosea; Mauritius, extinct), Cheirolaena (1; C. linearis; Antsiranana in Madagascar), Corchoropsis (1; C. tomentosa; East Asia to Japan), Paradombeya (1; P. sinensis; Burma, Yunnan), Pentapetes (1; P. phoenicea; tropical Asia), Trochetiopsis (3; T. ebenus, T. erythroxylon, T. melanoxylon; St. Helena), ‘Dombeya’ (>220; tropical Africa, Madagascar, Mauritius; paraphyletic), Trochetia (6; T. blackburniana, T. boutoniana, T. parviflora, T. triflora, T. uniflora: Mauritius; T. granulata: Réunion), Ruizia (1; R. cordata; Réunion), Andringitra (5; A. leiomacrantha, A. leucomacrantha, A. macrantha, A. moratii, A. muscosa; Madagascar), Eriolaena (c 10; the Himalayas, southern China, Southeast Asia), Helmiopsiella (2; H. leandrii, H. madagascariensis; Madagascar), Helmiopsis (9; Madagascar). – Tropical regions in the Old World, St. Helena, with their largest diversity in Madagascar. Leaves alternate (spiral). Epicalyx usually present. Sepals free or connate at base, with basal nectaries. Stamens (five or) ten (to c. 30). Filaments usually connate (rarely free). Staminodia antesepalous, elongate, forming short tube (sometimes absent). Tapetum usually secretory (sometimes amoeboid-periplasmodial). Secondary pollen display sometimes occurring. Pollen grains often porate, with spinulate exine. Pistil composed of (two to) five (or ten) connate carpels. Micropyle bistomal. Outer integument three or four cell layers thick. Inner integument four or five cell layers thick. Archespore sometimes multicellular. Nucellar cap sometimes present. Endocarp often pubescent. Seed with umbonate sarcotestal outgrowths. Cotyledons bilobate. n = 19, 20, 30 or higher. – Dombeyoideae may be sister to the remaining Malvadendrina (Nyffeler & al. 2005) or to Tilioideae (with low support; Alverson & al. 1999).

Tilioideae Arn., Botany: 100. 9 Mar 1832 [‘Tilieae’]

3/c 62. Tilia (c 45; temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere), Craigia (2; C. kwangsiensis, C. yunnanensis; China, northern Vietnam), Mortoniodendron (c 15; Mexico, Central America, northern Colombia). – Temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere south to China and northern Vietnam, Mexico, Central America. Ectomycorrhiza present. Leaves alternate (usually distichous), usually with horizontally conduplicate ptyxis. Petiole vascular bundle transection annular; petiole with medullary phloem strands and inverted bundles. Sepals free. Stamens and staminodia antepetalous (antesepalous sectors empty). Filaments free. Carpels antesepalous. Outer integument three or four cell layers thick. Inner integument four or five cell layers thick. Aril usually absent (sometimes present). Cotyledons plicate. n = 41, c. 80, 82. Stachyose and raffinose present (in phloem exudate in Tilia).

Brownlowioideae Burett in Notizbl. Bot. Gart. Berlin-Dahlem 9: 599, 605. 22 Jul 1926

9/c 90. Diplodiscus (12; Sri Lanka, West Malesia to the Philippines), Indagator (1; I. fordii; northern Queensland), Brownlowia (c 30; Southeast Asia, Malesia to Solomon Islands), Pentace (c 25; Burma, Southeast Asia, West Malesia), Pityranthe (2; P. trichosperma, P. verrucosa; Sri Lanka, southern China, Taiwan), Jarandersonia (4; J. paludosa, J. parvifolia, J. rinoreoides, J. spinulosa; Borneo), Christiana (5; C. africana, C. eburnea, C. macrodon, C. mennegae, C. vescoana; tropical Africa, Tahiti [extinct], tropical South America), Berrya (6; B. cordifolia, B. javanica, B. mollis, B. pacifica, B. papuana, B. rotundifolia; India, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, Malesia), Carpodiptera (5; C. africana, C. cubensis, C. hexaptera, C. mirabilis, C. simonis; tropical East Africa, the Comoros, southern Mexico, the West Indies, Trinidad). – Tropical regions in the Old World eastwards to Taiwan and the Solomon Islands, tropical America. Hairs often lepidote. Inflorescences axillary. Sepals splitting irregularly into two or three lobes, connate into campanulate calyx, persistent. Stamens c. 30, in antepetalous fascicles. Anthers with sagittate thecae. Staminodia petaloid, antesepalous (sometimes absent). Style one or stylodia several. Ovules approx. two per carpel. Fruit with persistent sepals. n = 10, 20.

Sterculioideae (Lindl.) Beilschm. in Flora 16(Beibl. 7): 86. 14 Jun 1833 [‘Sterculieae’]