TRICOLPATAE M. J. Donoghue, J. A.

Doyle et P. D. Cantino

Donoghue, Doyle et Cantino in Taxon 56: E26. Aug

2007

[Ranunculales+[Sabiaceae+Proteales+[Trochodendrales+[Didymelales+Gunneridae]]]]

RANUNCULALES Juss. ex Bercht. et

J. Presl

Berchtold et Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 215. Jan-Apr

1820 [‘Ranunculaceae’]

Berberidopsida

Brongn., Enum. Plant. Mus. Paris: xxv, 94. 12 Aug 1843

[’Berberineae’]; Ranunculopsida Brongn.,

Enum. Plant. Mus. Paris: xxvi, 96. 12 Aug 1843 [’Ranunculineae’];

Ranunculanae Takht. ex Reveal in Novon 2: 236. 13 Oct

1992; Ranunculidae Takht. ex Reveal in Novon 2: 235.

13 Oct 1992; Berberidanae Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant.

Vasc.: xxv, xxvi. 23 Dec 2001; Papaveranae Doweld,

Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.: xxv. 23 Dec 2001

Fossils Teixeiraea

lusitanica has been assigned to Ranunculales (and possibly to

Menispermaceae). It

is a fossilized male flower from the Late Aptian to the Early Albian of

Portugal. The spirally arranged floral parts are free, the outermost ones being

bracteate and grading into tepaloid parts. The 20 stamens have basifixed

anthers and the tectate-perforate pollen grains have a columellate

infratectum.

Habit Usually bisexual

(sometimes monoecious or dioecious, rarely polygamomonoecious), shrubs, lianas,

suffrutices, perennial, biennial or annual herbs (rarely trees).

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

ab initio superficially or deeply seated, or absent. Primary vascular tissue

consisting of one or several cylinders of vascular bundles, or of scattered

bundles. Secondary lateral growth normal, from cylindrical cambium, anomalous,

from normal successive cambia, or absent. Fusiform cambial initials storied

(not in Glaucidiaceae). Vessels

confined to central portions of fascicular areas (vessel restriction patterns,

with very few or no vessels touching rays). Vessel elements with simple or

scalariform (sometimes reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits alternate,

opposite or scalariform, bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements

fibre tracheids or libriform fibres (sometimes tracheids) with simple or

bordered pits, septate or non-septate (often also vasicentric tracheids). Wood

rays usually multiseriate (sometimes uniseriate), homocellular or

heterocellular, or absent. Axial parenchyma apotracheal, diffuse or

diffuse-in-aggregates or banded, or paratracheal, intervascular or scanty

vasicentric, banded, or absent. Sieve tube plastids S or Ss type. Nuclei

sometimes with dispersive P-protein. Nodes usually ≥3:≥3, trilacunar or

multilacunar with three or more leaf traces (rarely 1:1, 1:4 or 1:5–11,

unilacunar with one to many traces, or 2:2, bilacunar with two traces). Latex

cells and laticifers with white or coloured latex sometimes present. Idioblasts

with raphides sometimes present. Prismatic or rhomboidal calciumoxalate

crystals often frequent; crystal sand sometimes present. Calcium oxalate

crystals usually present in wood rays (not in Glaucidiaceae and Ranunculaceae).

Trichomes Hairs unicellular

och multicellular, usually uniseriate (sometimes multiseriate, rarely

branched), or absent; glandular hairs often present.

LeavesUsually alternate

(spiral or distichous; sometimes opposite), simple or compound, entire or

pinnately or palmately lobed, with supervolute, involute, conduplicate,

plicate, subplicate, reclinate, curved or equitant ptyxis. Stipules

intrapetiolar or absent; petiole base sometimes sheathing. Petiole vascular

bundle transection arcuate or annular. Venation pinnate or palmate,

actinodromous or acrodromous (rarely parallelodromous or flabellate). Stomata

usually anomocytic (sometimes paracytic, staurocytic or cyclocytic) or absent.

Cuticular wax crystalloids usually as irregularly shaped platelets or clustered

tubuli (Berberistype), dominated by nonacosan-10-ol (without

triterpenoids), or absent. Mesophyll sometimes with sclerenchymatous idioblasts

and mucilage cells. Idioblasts with ethereal oils absent. Leaf margin serrate,

serrate-dentate, spinose-serrate or glandular-serrate, with chloranthoid or

platanoid teeth, crenate or entire.

Inflorescence Terminal or

axillary, simple or compound, cymose, raceme-, head- or umbel-like, fascicle,

panicle, thyrsoid, spike, raceme, or flowers solitary. Floral prophylls

(bracteoles) single or pairwise (sometimes absent).

Flowers Usually actinomorphic

(sometimes zygomorphic or bisymmetric). Hypogyny. Perianth sometimes trimerous.

Tepals (three or) four to 15, spiral or whorled (rarely absent). Outer tepals

two or more, with imbricate or valvate (rarely open) aestivation, sepaloid or

petaloid, persistent or caducous, usually free. Inner tepals (staminodial in

origin?) one to 13, with imbricate or valvate (sometimes crumpled), free, often

with one or several nectaries at base (nectary sometimes absent). Disc

absent.

Androecium Stamens (one to)

three to more than 500, spiral or whorled. Filaments free or more or less

connate, free from tepals. Anthers basifixed to somewhat dorsifixed, usually

non-versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (rarely disporangiate), extrorse,

latrorse or introrse, usually longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits) or

valvate (dehiscing by longitudinal valves). Tapetum usually secretory (rarely

amoeboid-periplasmodial). Staminodia extrastaminal, petaloid and/or

nectariferous, or absent; female flowers sometimes with staminodia.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis usually simultaneous (rarely successive). Pollen grains di-

or tricolpate to polycolpate or -porate, di- or tricolporate, zono- or

pantoaperturate (sometimes syncolpate, rarely spiraperturate, clypeate or

inaperturate), usually shed as monads (rarely dyads or tetrads), usually

bicellular (sometimes tricellular) at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate,

with columellate infratectum, perforate, microreticulate, reticulate or

punctate, foveolate, striate, scabrate, spinulate, echinate, microechinate,

verrucate or psilate.

Gynoecium Carpels one

(monocarpellate or pseudomonomerous) to more than 100, spiral or whorled,

usually free (sometimes more or less connate), or pistil composed of one to

numerous carpels; carpel ascidiate, conduplicate or plicate, postgenitally

usually entirely occluded, without canal. Ovary superior, unilocular (apocarpy

or gynoecium monomerous) or trilocular to quinquelocular. Stylodia or style

single, simple, or absent. Stigma of various types, lobate to capitate

(sometimes decurrent), papillate or non-papillate, Dry or Wet type. Male

flowers sometimes with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation marginal

or basal (when ovule single, or when ovary unilocular), laminal-lateral or

marginal-lateral (when ovules several), or axile (when ovary plurilocular).

Ovules one to numerous per carpel, usually anatropous (sometimes

hemianatropous, rarely amphitropous or campylotropous), ascending, horizontal

or pendulous, usually apotropous (rarely epitropous), usually bitegmic

(sometimes unitegmic), usually crassinucellar (sometimes pseudocrassinucellar).

Micropyle endostomal or bistomal, sometimes Z-shaped (zig-zag). Archespore

unicellular to at least 15-celled. Nucellar cap usually present.

Megagametophyte usually monosporous, Polygonum type (rarely disporous,

Allium type, or tetrasporous, Adoxa type,

Fritillaria type or Peperomia type). Synergids sometimes with

a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells usually persistent, proliferating or

non-proliferating. Endosperm development ab initio usually nuclear (rarely

cellular). Endosperm haustoria chalazal or absent. Embryogenesis usually

onagrad (sometimes solanad, rarely caryophyllad or chenopodiad).

Fruit An assemblage of

follicles or achenes, a berry, or a loculicidal, septicidal or poricidal

capsule with basipetalous or acropetalous dehiscence (sometimes a

multifolliculus or a nut, rarely a lomentum with nut-like mericarps).

Seeds Aril usually absent.

Seed coat usually exotestal (rarely endotegmic). Testa often multiplicative

(sometimes thin). Exotesta palisade, with often thickened non-lignified cell

walls, or seeds more or less pachychalazal, with thin testa. Mesotesta,

endotesta and tegmen usually unspecialized. Exotegmen sometimes multiplicative.

Perisperm not developed. Endosperm scarce to copious (rarely absent), oily,

proteinaceous or starchy. Embryo small to large, undifferentiated to well

differentiated at dispersal, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons (one or) two.

Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = 6–9, 11–13,

15, 19, 21

DNA Nuclear gene AP3

present and usually triplicated.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin, rhamnocitrin; frequently additional

oxygenation at carbons 6 or 8 of ring A in contrast to magnoliid clades),

O-methylated flavonoids, flavones, isoprenylated flavonoids, cyanidin,

delphinidin, dihydrochalcones, diterpenoids, tannins, cardioactive

bufadienolides, Digitalis cardenolides, poisonous sesquiterpene

lactones, caffeic acid, benzylisoquinoline and aporphine alkaloids

(benzyltetrahydroisoquinoline and aporphine derivatives in dimeric form,

bulbocapnine and other aporphines, morphinanes, pavines, isopavines,

dehydrogenated benzophene anthridines, reduced benzophene anthridines,

tyrosine-derived berberine, tetrahydroberberines, berberidine, protopines,

rhoeadines, narceines, spirobenzyl isoquinolines, hydrastine, protopine,

quaternary magnoflorine and its precursor corytuberine), hasubanane alkaloids

(protostephanines, erythrinanes, cocculolidines, morphines, quettamine-morphine

dimers, hasubanonines, acutumines, etc.), azafluoranthene alkaloids,

tropoloisoquinoline alkaloids, protoberberine alkaloids, diterpene alkaloids

(aconitine, methyl lycaconitine etc.), quinolizidine alkaloids (e.g.

darvasamine), pyrrolizidine alkaloids as macrocyclic diesters, tyrosine-derived

cyanogenic glycosides, lignan-β-glycosides, ranunculins (glucosides),

triterpene saponins, steroidal saponins, meconic acid, chelidonic acid, fumaric

acid, nitrophenyl ethan, phenylic cinnamide, furofuran lignans, mannitol, and

glaupalol (a furanocoumarin) present. Ethereal oils, prodelphinidin, and

flavonoids and tannins containing a trihydroxylated B-ring (gallic and ellagic

acid derivatives) not found.

Systematics Ranunculales are sister-group

to the remaining Tricolpatae.

Euptelea is sister to all other Ranunculales, according to

most molecular analyses. The majority of Ranunculales are characterized

by wide and tall multiseriate wood rays little altered during ontogeny, and

relatively intact extensions of primary rays. These contrast with multiseriate

rays dominating in other Tricolpatae, in which the large primary rays

are rapidly broken into smaller segments during stem and root growth. In

general, multiseriate rays in Ranunculales are composed of

procumbent cells with the exception of one or two layers of upright sheathing

cells.

The clade [[[Lardizabalaceae+Circaeasteraceae]+[Menispermaceae+[Berberidaceae+ [Hydrastidaceae+Glaucidiaceae]+Ranunculaceae]]]+[Papaveraceae s.lat.]] is

characterized by the following potential synapomorphies (Stevens 2001 onwards):

vessel elements with simple perforation plates, present in diagonal groups;

presence of nucleated libriform fibres and vasicentric tracheids; leaves with

palmate secondary venation; and Wet type stigma. Herbaceous growth and woody

habit have evolved several times in the two main clades above

Euptelea. Likewise, petaloid tepals have originated several times from

staminodial stamens (e.g. in Berberidaceae, Lardizabalaceae, Ranunculaceae; Drinnan &

al. 1994, etc.). In Ranunculaceae, the petaloid

tepals have a single vascular strand, share parastichs with the stamens, are

similar to stamens in their early development, and are often peltate.

Pteridophyllum and Papaveraceae have among others

the following potential synapomorphies in common (Stevens 2001 onwards):

herbaceous growth; roots diarch, i.e. lateral roots tetrastichous; perianth

differentiated into outer sepaloid and inner petaloid tepal whorls; sepaloid

tepals two, median; petaloid tepals four; carpels at least two collateral,

occluded by secretion; placentation parietal; capsule septicidal, with

persistent woody placenta; and endotesta well developed.

The second main clade has the topology [[Lardizabalaceae+Circaeasteraceae]+ [Menispermaceae+[Berberidaceae+Ranunculaceae]]] and the

potential synapomorphies: wide wood rays; trimerous flowers; outer and inner

tepals and stamens opposite each other; outer tepals with three or more

vascular traces; and triplication of nuclear gene

AP3. Both Lardizabalaceae and Circaeasteraceae have

extrorse anthers and cellular endosperm development.

The clade [Menispermaceae+[Berberidaceae+[[Hydrastis+Glaucidium]+Ranunculaceae]]] has the

benzylisoquinoline berberine and nuclear endosperm development. According to

Stevens (2001 onwards), the clade [Berberidaceae+[[Hydrastis+Glaucidium]+Ranunculaceae]] has the

potential synapomorphies: usually herbs with non-tuberous rhizome; bright

yellow roots and rhizome due to presence of berberine; roots diarch; lateral

roots tetrastichous; nodes often multilacunar; vascular bundles V-shaped, in

herbaceous species often closed, scattered or arranged in concentric cylinders;

broad leaf base; presence of petaloid staminodial nectaries; outer integument

at least four cell layers thick; presence of nucellar cap; endosperm with

reserves other than oils or proteins; and loss of mitochondrial intron

coxII.i3. Hydrastis, Glaucidium and Ranunculaceae share the

synapomorphies: uniseriate perianth; and numerous spiral stamens and carpels.

Hydrastis and Glaucidium have vessel elements with simple and

scalariform perforation plates, medullary vascular bundles, flattened vascular

bundles; petiole vascular bundles annular in cross-section; medullary petiole

vascular bundles; no palisade mesophyll; distichous leaves; flowers solitary

and terminal; no nectaries; bilobate stigma; outer integument four to 13 and

inner integument two to five cell layers thick; unmodified antipodal cells; and

also abaxial dehiscence of follicle.

|

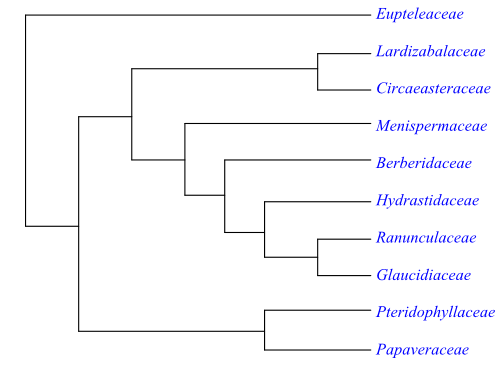

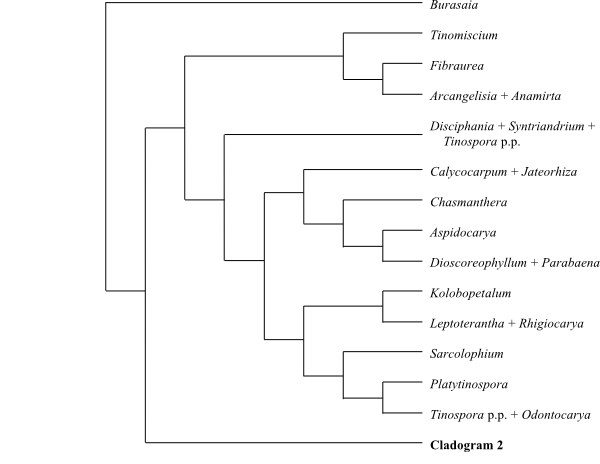

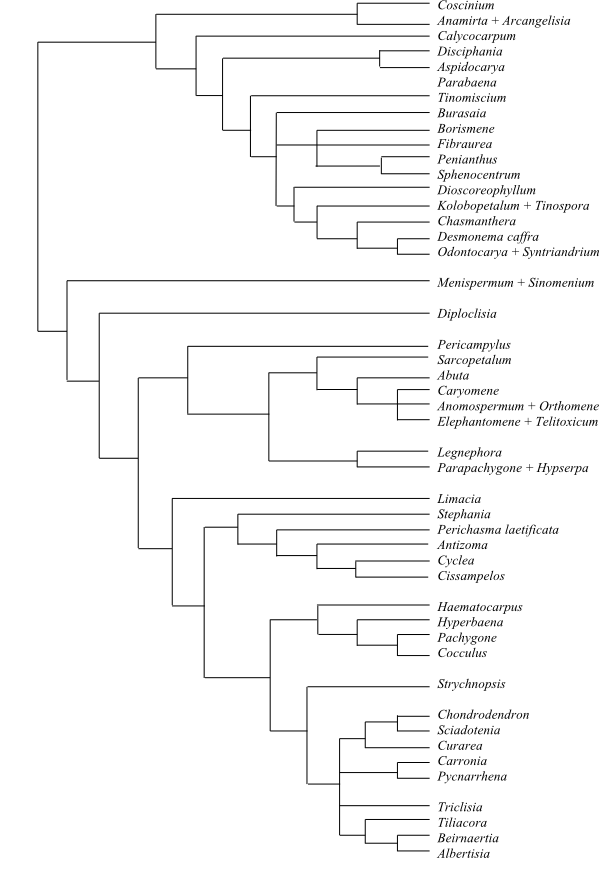

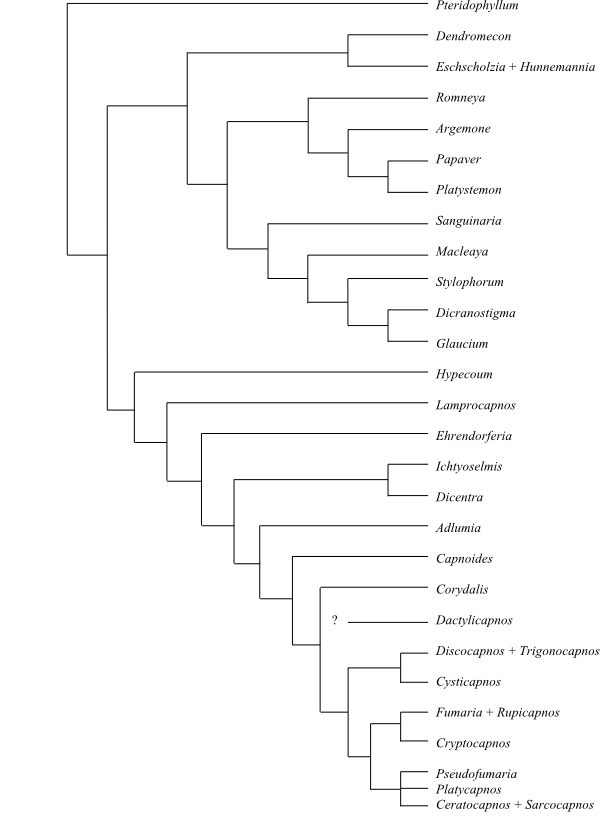

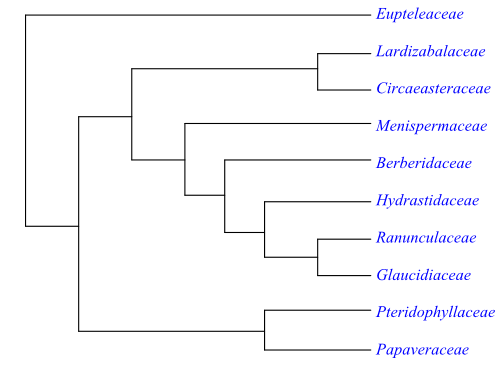

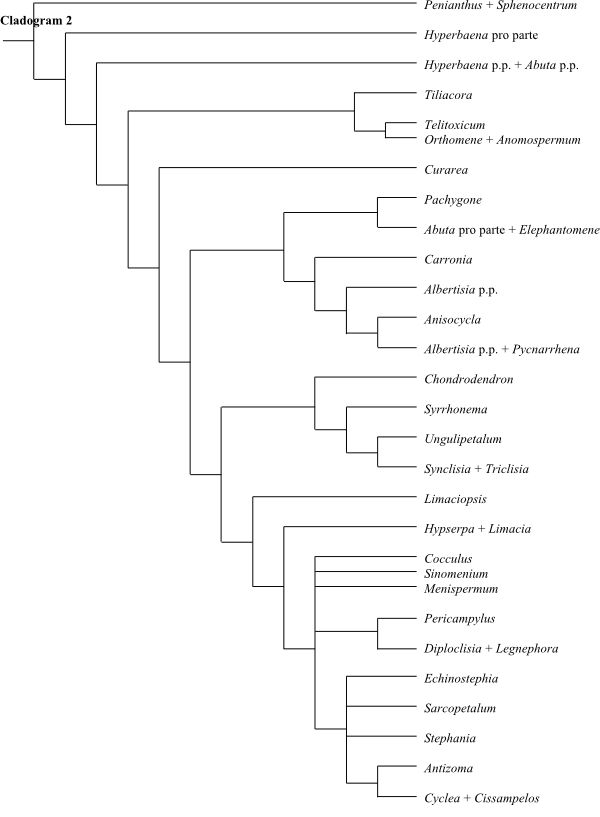

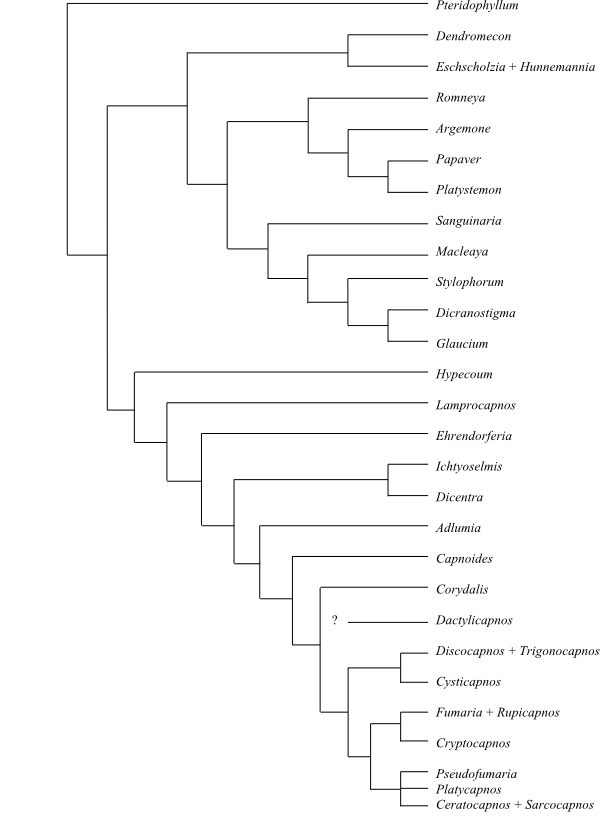

Cladogram of Ranunculales based on

DNA sequence data (Soltis & al. 2011). Euptelea is usually

sister to the remainder with high bootstrap support and, likewise, the

clade [Papaveraceae+Pteridophyllum]

is sister to the remaining Ranunculales, often

with a bootstrap support of 100%. The other clades show high support

varying between 75% and 100%. Circaeasteraceae

are sister to Lardizabalaceae

with a bootstrap support of 78%. According to Wang & al. (2009),

Pteridophyllum (Pteridophyllaceae)

is nested inside Papaveraceae as sister

to Hypecoum. Until this hypothesis has been further confirmed,

Pteridophyllum is treated as sister to Papaveraceae,

according to, e.g., Kadereit & al. (1994, 1995).

|

de Jussieu, Gen. Plant.: 286. 4 Aug 1789

[’Berberides’], nom. cons.

Podophyllaceae DC.,

Syst. Nat. 1: 126. 1-15 Nov 1817 [’Podophylleae’], nom. cons.;

Berberidales Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin:

226. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Berberideae’];

Leonticales Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 217.

Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Leonticinae’];

Podophyllales Dumort., Anal. Fam. Plant.: 45. 1829

[’Podophyllarieae’]; Diphylleiaceae

Schultz Sch., Nat. Syst. Pflanzenr.: 328. 30 Jan-10 Feb 1832;

Nandinaceae Horan., Prim. Lin. Syst. Nat.: 90. 2 Nov

1834 [’Nandinaceae (Berberideae)’];

Epimediaceae Menge, Cat. Plant. Grudent. Gedan.: 122.

1839 [’Epimedineae’]; Leonticaceae Airy

Shaw in Kew Bull. 18:263. 8 Dec 1965; Ranzaniaceae

(Kumaz. et Terab.) Takht. in Bot. Žurn. 79(1): 96. Jan 1994;

Nandinales Doweld in Byull. Mosk. Obshch. Ispyt.

Prir., Biol. 105(5): 60. 9 Oct 2000

Genera/species

12–14/>600

Distribution Eurasia from

Western Europe to Malesia, North Africa, East African mountains, North and

Central America, mountains in South America.

Fossils Fossil representatives

of Berberis are known from the Oligocene onwards in the Northern

Hemisphere.

Habit Bisexual, evergreen or

deciduous shrubs or biennial to perennial rhizomatous or tuberous herbs (rarely

trees). Roots and rhizome often bright yellow inside due to presence of

berberine.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

ab initio superficially or deeply sited (pericyclic). Primary medullary rays

wide in Nandina. Primary vascular tissue consisting of one or more

cylinders of bundles or scattered bundles. Secondary lateral growth absent or

from normal cylindrical cambium. Xylem V-shaped. Vessel elements with usually

simple (in Berberis sometimes also scalariform) perforation plates;

lateral pits usually opposite or alternate (in Vancouveria scalariform

or pseudoscalariform), bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements

usually libriform fibres (in Nandina also fibre tracheids; in

Jeffersonia tracheids) with usually simple pits (in Nandina

bordered pits also), septate or non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood

rays multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma usually

absent (rarely vasicentric scanty). Wood elements partially storied. Sieve tube

elements Ss type. Nodes ≥3:≥3, trilacunar or multilacunar with three or

more leaf traces. Secondary tissue often yellow due to presence of berberine.

Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals often abundant. Wood rays often with

rhomboidal crystals.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or

multicellular, uniseriate, or absent.

Leaves Alternate (sometimes in

a basal rosette), simple or compound (pinnately or palmately compound; in

Nandina and sometimes Leontice bipinnate; in

Berberis trifoliolate or unifoliolate), entire or lobate, with

conduplicate, reclinate, equitant or curved ptyxis; leaves of long shoots in

Berberis usually modified into spines. Stipules rudimentary,

intrapetiolar and caducous, or absent; leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular

bundle transection annular or arcuate. Venation pinnate or palmate. Stomata

anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids usually as clustered tubuli

(Berberis type), chemically dominated by nonacosan-10-ol (in

‘Podophyllum’ as solid rodlets sometimes aggregated to larger

units). Idioblasts with ethereal oils absent. Leaf margin serrate (sometimes

serrate-dentate or spinose-serrate), with chloranthoid teeth, or entire.

Inflorescence Terminal or

axillary, spike, raceme or fasciculate etc. (in Nandina panicle), or

flowers solitary.

Flowers Actinomorphic.

Hypogyny. Tepals (eight to) twelve (to 15) (3+3+3, 3+3, 2+2+2, or 2+2; in

Epimedium 4+4+4 or 4+5+5; absent in Achlys) in three to six

(rarely seven) series (in Nandina slightly spiral), with imbricate

aestivation, free, all tepals in Nandina sepaloid; outer tepals three

to nine (in Nandina c. 20 to c. 50), in two series, sepaloid or

petaloid (or bracts?), caducous; inner tepals six to twelve, in two to four

series, outer series petaloid sepals?, inner two or three series petaloid

staminodia? with nectaries (in Nandina nectar secreting staminodia;

absent inAchlys, Diphylleia and ‘Podophyllum’).

Four inner tepals in Epimedium with four nectariferous spurs. Disc

absent.

Androecium Stamens (three to)

six (to 19), usually as many (sometimes twice as many) as inner petals (in

Achlys seven to 15; in Epimedium 2+2), in one whorl,

alternisepalous, antepetalous, or in two or more whorls. Filaments free from

each other, free? from or adnate? at base to tepals. Anthers basifixed,

non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, usually extrorse (often with valves directed

ab initio backwards, later usually inverted and turned up-side-down, with

pollen grains against floral centre; in Dysosma and Nandina

introrse), usually valvicidal (dehiscing by valves; in Dysosma,

Nandina and ‘Podophyllum’ longicidal, dehiscing by

longitudinal slits); connective sometimes slightly prolonged. Tapetum secretory

or amoeboid-periplasmodial, with multinucleate cells. Staminodia three to nine,

petaloid, extrastaminal (or absent?).

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis usually simultaneous (in Berberis and

Ranzania? at least sometimes successive). Pollen grains usually

tricolpate (rarely hexa- to dodecacolpate or spiraperturate; in

Berberis sometimes irregularly polysyncolpate, spiraperturate or

clypeate [with surface divided into platelets]; in Ranzania

hexacolpate), usually shed as monads (in Ranzania etc. dyads; in some

species of ‘Podophyllum’ tetrads), bicellular at dispersal. Exine

tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, usually perforate,

microreticulate, striate-reticulate, psilate-punctate, punctate-striate,

echinate, gemmate (in Diphylleia spinulate), in Achlys,

Epimedium, Jeffersonia, and Vancouveria striate

(with compound layer of striae).

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

(seemingly?) one carpel (pseudomonomerous gynoecium developed from two or three

connate carpels?); carpel secondarily ascidiate (primarily plicate, rarely

ascoplicate), seemingly occluded postgenitally by secretion; closure of carpels

sometimes delayed. Ovary superior, unilocular. Style short or absent. Stigma

wide, often trilobate (rarely quadrilobate), papillate or non-papillate, Dry or

Wet type. Carpellary walls in Caulophyllum etc. not enclosing ripening

blue seeds. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation basal

(when single ovule) or marginal-lateral (when several ovules). Ovules one to

numerous per ovary (in Achlys one ovule; in Nandina two

ovules, one of which degenerating), usually anatropous (sometimes

hemianatropous or campylotropous), ascending, horizontal or pendulous,

bitegmic, crassinucellar to pseudocrassinucellar. Micropyle bistomal, often

Z-type (zig-zag). Outer integument five to eleven cell layers thick. Inner

integument two to five cell layers thick. Parietal tissue one or two cell

layers thick or absent. Nucellar cap six to eight cell layers thick, formed by

periclinal divisions from apical cells of megasporangial epidermis.

Megagametophyte usually monosporous, Polygonum type (in

Caulophyllum at least sometimes tetrasporous, Peperomia

type). Synergids sometimes with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells

persistent, endopolyploid, with large nuclei, non-proliferating. Endosperm

development ab initio usually nuclear (sometimes cellular). Endosperm haustoria

usually chalazal (absent in some genera, e.g. in ‘Podophyllum’).

Embryogenesis onagrad (or variations of this type).

Fruit Usually a berry or a

follicle (in Achlys a nut; in Jeffersonia a capsule; in

Gymnospermium a papery not completely closed envelope; fruit in

Caulophyllum entirely strongly reduced, with fleshy seeds growing out

through carpellary wall).

Seeds Elaiosome and aril

usually absent (more or less rudimentary aril present in, e.g.,

Nandina, Epimedium, Jeffersonia and certain species

of Berberis). Seed coat usually exotestal (in Nandina

endotegmic). Testa often multiplicative. Exotesta palisade, usually well

developed, in Berberis with thick-walled lignified cuboid cells.

Mesotesta and endotesta unspecialized. Tegmen usually unspecialized (endotegmen

in Nandina sclerotic). Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious,

oily or with hemicellulose. Embryo very small, straight, rudimentary, without

chlorophyll. Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = 6

(Podophylloideae); n = 7 (Berberidoideae); n = 8, 10

(Nandinoideae)

DNA Plastid inverted repeat

expanded by 11.5 kb into large single copy region in Berberis. Plastid

gene rps7 lost in Podophyllum. Mitochondrial intron

coxII.i3 lost. Triplication of nuclear gene

AP3.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), isoprenylated flavonoids, cyanidin,

delphinidin, tannin, frequent caffeic acid, benzylisoquinoline alkaloids

(berberine, magnoflorine, protopine etc.), aporphine alkaloids, quinolizidine

alkaloids (in Caulophyllum, Leontice and

Gymnospermium; in Gymnospermium also darvasamine), cyanogenic

compounds (in Nandina tyrosine-derived), and saponins present.

Lignan-β-glycosides and similar compounds accumulated in Epimedium,

‘Podophyllum’ and Diphylleia (Dysosma?,

Vancouveria?). Ellagic acid not found.

Use Ornamental plants, fruits

(Berberis), medicinal plants, dyeing (yellow) substances.

Systematics Berberidaceae are

sister-group to the clade [Ranunculaceae+[Hydrastis+Glaucidium]].

Nandina was

sister to the remaining Berberidaceae in several

molecular analyses (e.g. Kim & Jansen 1998). However, Wang & al. (2007)

identified the Podophylloideae clade as sister-group to

Berberidoideae in a strict sense, in which Nandina were

nested in a clade sister to [Berberis+Ranzania].

The subdivision below follows the latter alternative, although the support for

this topology is at most moderate.

Podophylloideae Eaton,

Bot. Dict., ed. 4: 38. Apr-Mai 1836 [‘Podophylleae’]

6–8/c 90. Epimedium

(55–60; the Mediterranean and North Africa to southwestern Asia, western

Himalayas, northeastern Asia, Japan), Jeffersonia

(2; J. dubia: Manchuria, northern China, the Korean Peninsula; J.

diphylla: eastern United States), Achlys (2–3;

A. californica, A. triphylla: southwestern Canada, western

United States; A. japonica: Japan), Bongardia (1; B.

chrysogonum; Greece to Afghanistan), ‘Podophyllum’

(14; the Himalayas to East Asia, southeastern Canada, eastern United States;

paraphyletic; incl. Diphylleia

and Dysosma?), Diphylleia

(3; D. sinensis: western China, D. grayi: central and

northern Japan, Sakhalin; D. cymosa: eastern United States; in Podophyllum?),

Dysosma (10–12; Tibet, China, Vietnam; in Podophyllum?),

Vancouveria

(3; V. chrysantha, V. hexandra, V. planipetala;

western United States). – Temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere.

Lowermost inflorescence branch arising from axil of reduced leaf. Outer tepals

four to 18 (absent in Achlys). Inner

tepals four to nine (absent in Achlys), with

or without nectariferous spurs. Stamens in Achlys seven to

15, in ‘Podophyllum’

up to 19. Anthers longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits).

Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains sometimes shed as dyads or tetrads.

Pollen wall development by centripetal furrowing. Exine usually striate

(sometimes spinulate). Gynoecium arising from two carpellary primordia. Ovules

one to numerous per carpel. Micropyle sometimes bistomal. Integuments lobate.

Inner integument two or three cell layers thick. Megasporocytes in Diphylleia

several. Parietal tissue one or two cell layers thick (sometimes absent). Fruit

an achene, a berry or a follicle (also with transverse dehiscence). Aril

rudimentary or absent. Testa multiplicative. n = 6. Lignan-β-glycosides and

similar compounds often accumulated. – Podophylloideae may be

sister-group to [Nandinoideae+Berberidoideae].

[Nandinoideae+Berberidoideae]

Tepals with a single trace. Gynoecium

arising from two or three carpellary primordia. Stigma usually Wet type.

Nandinoideae Heintze,

Cormofyt. Fylog.: 101. 1 Jun 1927

4/15. Nandina (1;

Nandina domestica; central China?); Caulophyllum

(3; C. robustum: northeastern Asia; C. giganteum, C.

thalictroides: southeastern Canada, eastern United States),

Gymnospermium (12; southern Balkan Peninsula, Iran, Central Asia,

China, the Korean Peninsula), Leontice (3; L. leontopetalum:

southeastern Europe to North Africa; L. armeniacum: Turkey to Iran;

L. incerta: Central Asia). – East Europe to East Asia. Primary

medullary rays wide. In Nandina also

fibre tracheids present. Petiole concave at base. Inflorescence paniculate,

with lowermost branch arising from axil of expanded leaf. Tepals sepaloid,

usually with three traces. Outer tepals in Nandina c.

20–50, spiral. Inner tepals (’petals’) six. Nectary in Nandina

absent. Petaloid staminodium and stamen developing from single common

primordium. Anthers in Nandina

longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Pollen grains in Nandina with

massive endexine. Ovules one or two (to four) per carpel, (in Nandina two,

one of which degenerating). Megasporangium in Nandina early

absorbed. Fruit a berry or with evanescent or bladder-like pericarp. Funicle

often swollen. Seed coat in Nandina

endotegmic, with thin-walled testal cells. Exotesta and mesotesta crushed (Nandina).

Endotestal cells in Nandina

crystalliferous. Endotegmic cells in Nandina

enlarged, lignified, thickened particularly on inner side, crystalliferous.

Embryo minute. n = 8, 10. Protopine (a benzylisoquinoline alkaloid) and in Nandina

tyrosine-derived cyanogenic compounds present.

Berberidoideae Eaton,

Bot. Dict., ed. 4: 41. Apr-Mai 1836

2/>500. Berberis

(>500; Europe, the Mediterranean, the Atlas Mountains, East African

mountains, temperate Asia, North to South America), Ranzania (1;

R. japonica; Japan). – Temperate and mountainous regions, North

Africa, South America, with their highest diversity in East Asia and eastern

North America. Usually shrubs. Phellogen also pericyclic. Vessel elements

usually with simple (in Berberis

sometimes scalariform) perforation plates. Leaves imparipinnate or

unifoliolate, with conduplicate to curved ptyxis. Stipules numerous. Petiole

vascular bundles in Berberis

arcuate. Venation sometimes pinnate. Leaf margin usually glandular- or

spinose-dentate (sometimes entire). Lowermost inflorescence bransch arising

from axil of reduced leaf. Outer tepals three to twelve. Nectar often secreted

from paired nectaries at base of four or six inner petaloid staminodia. Stamens

(four to) six (to more than 20). Anthers usually dehiscing by valves (rarely

slits), often sensitive. Tapetum amoeboid-periplasmodial. Pollen grains

6–12-colpate or spiraperturate etc. Exine striate-reticulate, often

undifferentiated. Placentation basal-lateral; placentae sometimes

protruding-diffuse and vascularized. Ovules one to numerous per carpel.

Megasporocytes sometimes several. Parietal tissue approx. two cell layers

thick. Endosperm development nuclear or cellular. Fruit a berry. Embryo

elongate, with relatively long radicula. n = 7.

|

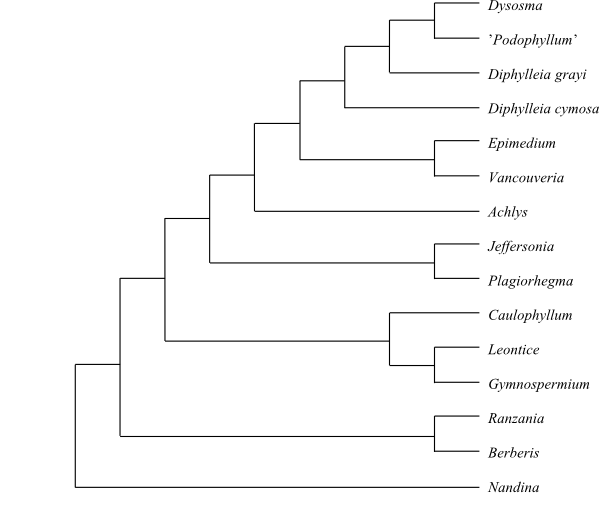

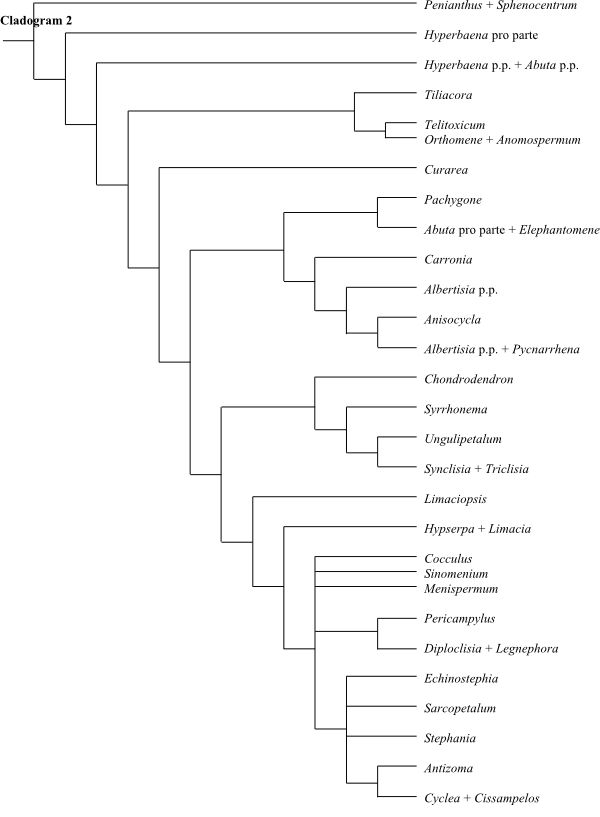

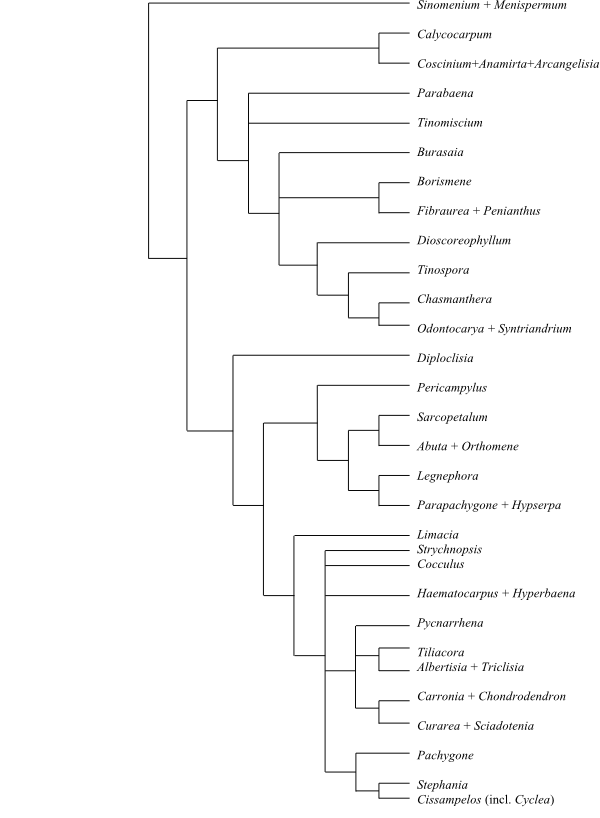

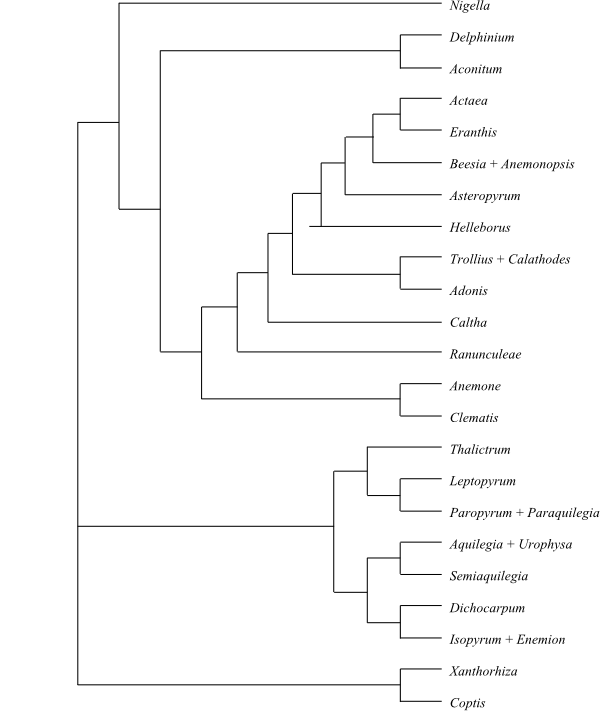

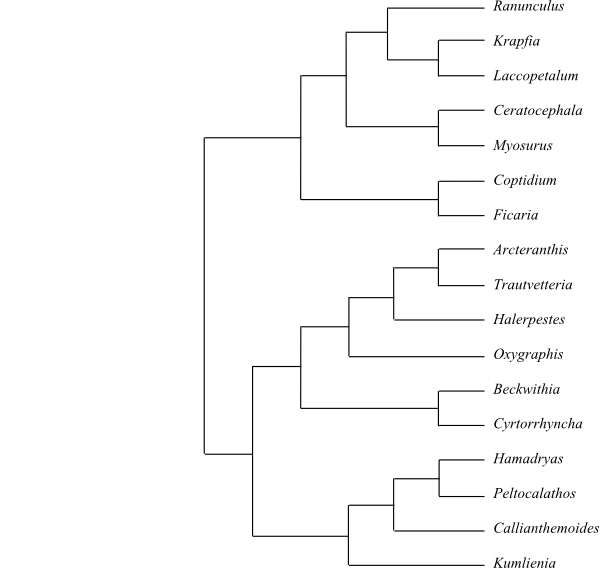

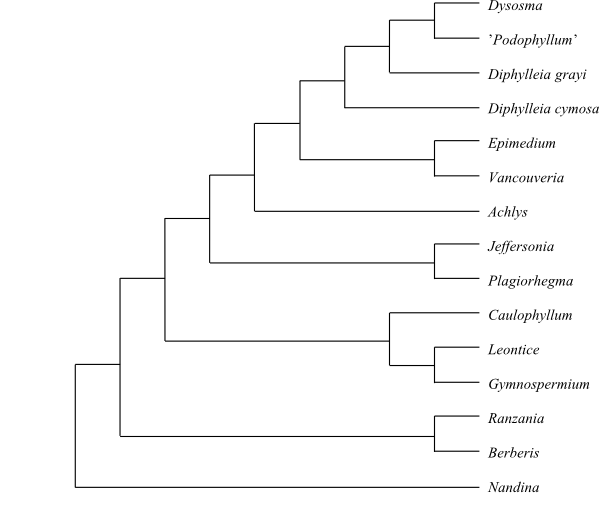

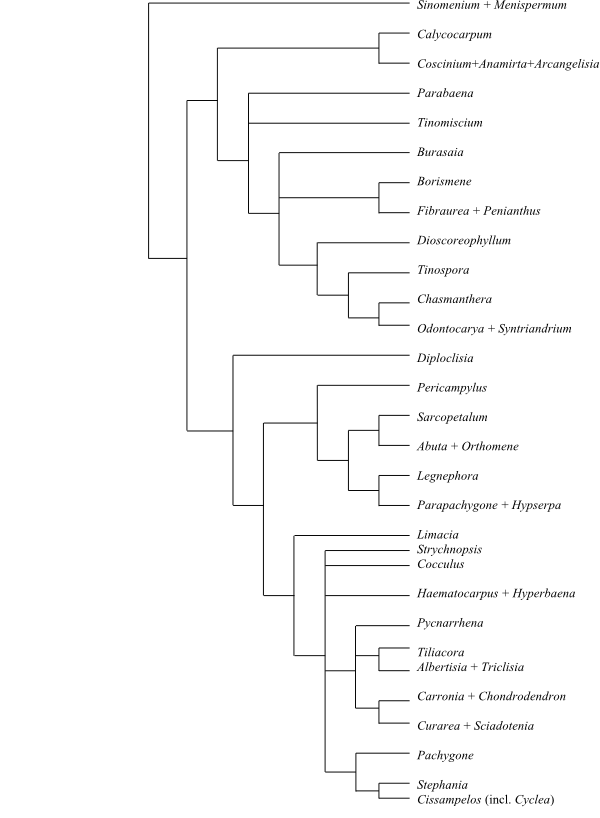

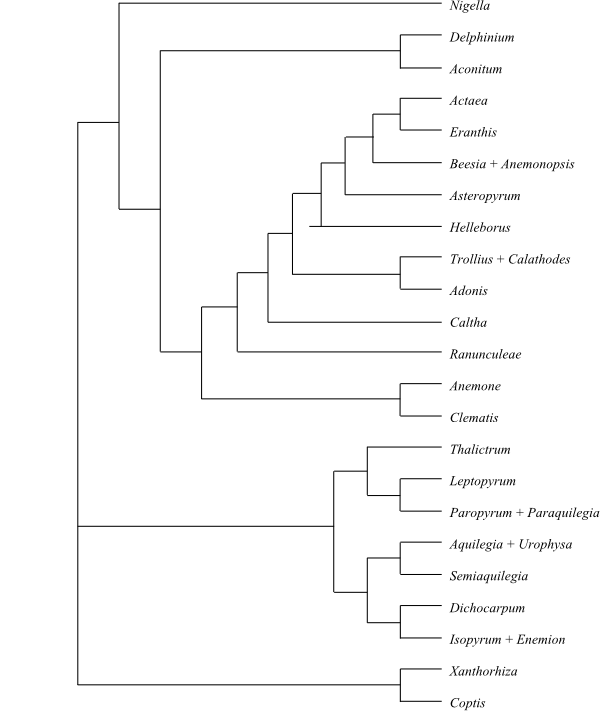

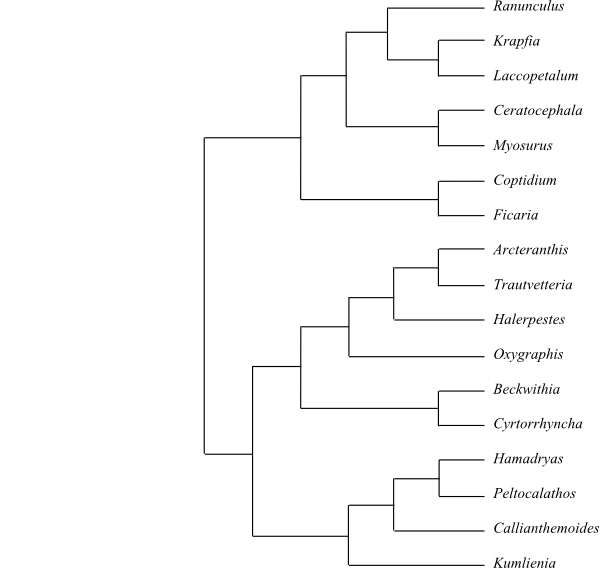

Cladogram of Berberidaceae based

on DNA sequence data (Kim & Jansen 1998).

|

|

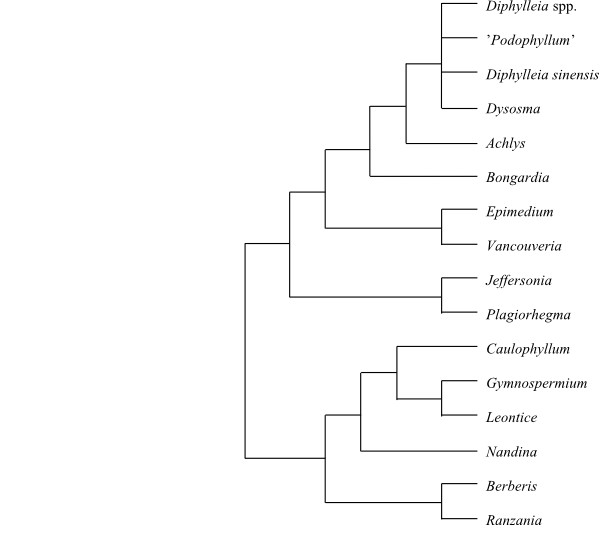

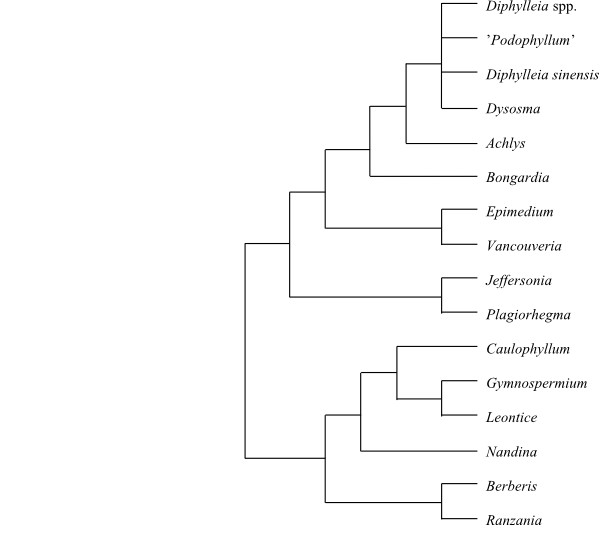

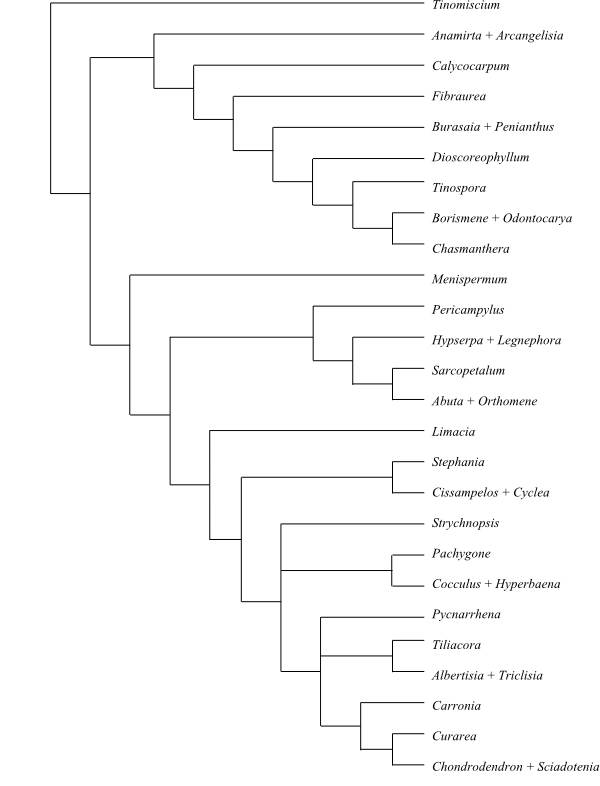

Cladogram of Berberidaceae based

on DNA sequence data (Wang & al. 2007)

|

Hutchinson, Fam. Fl. Pl. 1: 98. 15 Jan 1926, nom.

cons.

Kingdoniaceae A. S.

Foster ex Airy Shaw in Kew Bull. 18: 262. 8 Dec 1965;

Circaeasterales Takht., Divers. Classif. Fl. Pl.: 97.

24 Apr 1997

Genera/species 2/2

Distribution The Himalayas,

southwestern, western and northwestern China.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, annual or

perennial (Kingdonia) or annual (Circaeaster) herbs.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza

endotrophic (Kingdonia). Phellogen absent. Vessel elements usually

with simple (in Kingdonia sometimes scalariform) perforation plates,

bordered pits absent? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements?, non-septate? Wood

rays absent. Axial parenchyma absent? Sieve tube plastids? Nodes 1:1

(Circaeaster) or 1:1–4 (Kingdonia), unilacunar with one or

four leaf traces, respectively. Crystals?

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or

multicellular, uniseriate, uncinate (on surface of achenes in

Circaeaster), or absent.

Leaves Alternate (in

Circaeaster in basal rosette; in Kingdonia usually only a

single basal leaf, sometimes distichous), simple, entire or palmately lobed,

with ? ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle

transection arcuate? Venation flabellate (open-dichotomously branched), with

branches running into leaf teeth. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax

crystalloids as clustered tubuli of Berberis type, dominated by

nonacosan-10-ol (Circaeaster). Leaf margin serrate.

Inflorescence Flowers

inCircaeaster in terminal, compound thyrsoid inflorescences; flowers

in Kingdonia terminal, solitary, long-pedunculate (scapose). Floral

prophyll (bracteole) in Kingdonia adaxial, in Circaeaster

absent.

FlowersAlmost actinomorphic,

small. Hypogyny. Tepals with valvate aestivation, spiral, persistent, in

Circaeastertwo or three scale-like sepaloid, in Kingdonia

(four or) five to seven petaloid. Kingdoniawith eight to 13

intratepalous clavate glistening glands (nectar-secreting staminodia?). Nectary

absent in Circaeaster. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens

inCircaeaster usually two (sometimes one or three), alternitepalous,

in Kingdonia three to eight. Filaments free from each other and from

tepals. Anthers in Circaeaster basifixed, non-versatile,

disporangiate, introrse to latrorse, in Kingdonia tetrasporangiate,

extrorse, valvicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal valves). Tapetum secretory.

Staminodia in Circaeaster one sepaloid or absent, in

Kingdonia eight to 13 extrastaminal, apically nectariferous and

petaloid.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tricolpate (sometimes

tricolporate?), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine (tectate to)

semitectate, with columellate infratectum, striate-reticulate (with compound

layer of fine striae).

Gynoecium Carpels usually two

(sometimes one or three; Circaeaster) or three to nine

(Kingdonia), short- to long-stalked, free; carpel ascidiate, occluded

by secretion? Ovary superior, unilocular (monomerous or apocarpous). Stylodia

short (Circaeaster) or subulate and recurved (Kingdonia).

Stigma somewhat oblique, papillate (Circaeaster), Wet? type.

Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation

subapical-marginal. Ovules two submarginal (Circaeaster, upper one

degenerating) or one (Kingdonia) per carpel, orthotropous

(Circaeaster) or hemianatropous (Kingdonia), pendulous,

unitegmic, incompletely tenuinucellar, with meiocyte hypodermal at apex of

megasporangium. Integument in Circaeaster approx. two cell layers

thick (degenerating following fertilization), in Kingdonia two to five

cell layers thick. Megagametophyte in Kingdonia monosporous,

Polygonum type, in Circaeaster tetrasporous, Adoxa

type (tetranucleate or octanucleate). Endosperm formation at least in

Circaeaster cellular (in Kingdonia helobial?). Endosperm

haustorium chalazal (Circaeaster). Embryogenesis chenopodiad.

Fruit An achene or assemblage

of achenes.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa thin

or absent (degenerating; in Circaeaster replaced by inner epidermis of

pericarp and outer layer of endosperm). Perisperm not developed. Endosperm

copious. Embryo small (Circaeaster) or fairly large

(Kingdonia), straight, chlorophyll? Hypocotyl in Circaeaster

strongly elongated. Cotyledons two, linear, persistent (Circaeaster).

Germination phanerocotylar (Circaeaster). Leaves in

Circaeaster at apex of elongated hypocotyl.

Cytology n = 9

(Kingdonia), n = 15 (Circaeaster)

DNA

Phytochemistry Virtually

unknown. Flavonols? Cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Unknown.

Systematics Circaeaster

(1; C. agrestis; northwestern Himalayas from Kumaun in India through

Nepal to southeastern Tibet and northwestern Yunnan, and the Kansu and Shensi

mountains in northwestern China), Kingdonia (1; K. uniflora;

western and northwestern China).

Circaeasteraceae are

sister group to Lardizabalaceae.

Wilhelm, Samenpflanzen: 17. Oct 1910, nom.

cons.

Eupteleales Hu ex

Reveal in Phytologia 74: 174. 25 Mar 1993;

Eupteleanae Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.: xxv. 23

Dec 2001; Eupteleineae Shipunov in A. Shipunov &

J. L. Reveal, Phytotaxa 16: 63. 4 Feb 2011

Genera/species 1/2

Distribution Eastern

Himalayas, Assam, southwestern and central China, Japan.

Fossils Fossilized leaves,

pollen grains and fruits have been found in Paleocene to Miocene layers in

several places in the Northern Hemisphere.

Habit Usually bisexual

(sometimes unisexual male), deciduous trees.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

ab initio cortical. Vessel elements with scalariform or partially reticulate

perforation plates; lateral pits usually opposite to intermediary (sometimes

alternate or scalariform), bordered pits. Vessel restriction patterns absent.

Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids with usually bordered

(sometimes simple) pits, non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate,

heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse, diffuse-in-aggregates, or

in tangential bands. Multiseriate phloem rays strongly sclerified. Sieve tube

plastids S type, with approx. ten globular starch grains. Nodes 1:5–11,

unilacunar with five to eleven leaf traces. Medulla and petioles with secretory

cells, tanniniferous cells and cells with cluster crystals.

Trichomes Hairs present on

young leaves, uniseriate, caducous, or absent.

Leaves Alternate (spiral),

simple, entire, with subplicate-conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath

absent. Petiole base hollow; petiole vascular bundles? Venation pinnate,

craspedodromous, with lateral veins ascending and running almost to leaf teeth,

or palmate. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids absent or as

clustered tubuli (Berberis type), chemically dominated by

nonacosan-10-ol. Mesophyll without sclerenchymatous idioblasts. Calciumoxalate

druses present. Idioblasts with ethereal oils absent. Leaf margin

glandular-serrate, with platanoid teeth (each gland with an apical cavity).

Inflorescence Axillary, with

flowers one or few together in raceme- or umbel-like fasciculate inflorescence.

Lowermost flowers often with one or two floral prophylls (bracteoles).

Flowers Bisymmetric, small,

bent downwards. Hypogyny? Tepals absent. Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens six to c.

20, in one whorl. Filaments short or somewhat elongated, filiform, free.

Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, latrorse, valvicidal

(dehiscing by longitudinal valves), horizontally somewhat widened; connective

prolonged. Tapetum secretory, with uninucleate to quadrinucleate cells.

Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains tricolpate or penta- to

heptacolpate (rarely tetracolpate), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal.

Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, perforate to

microreticulate, verrucate.

Gynoecium Carpels six to 18

(to 31), whorled, free (apocarpous); carpel plicate and ascidiate

(intermediary), postgenitally closed, without canal, stipitate. Ovary

superior?, unilocular. Style absent. Stigma decurrent, not reaching carpellary

apex (due to asymmetrical growth of carpel), brush-like, papillate (with long

unicellular papillae), Dry or slightly Wet type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation lateral

(submarginal). Ovules usually one to three (rarely four) per carpel,

anatropous, pendulous, apotropous or epitropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar.

Micropyle bistomal. Outer integument two to five cell layers thick. Inner

integument (except its inner epidermis) crushed, two or three cell layers

thick. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm

development cellular. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis caryophyllad or

solanad.

Fruit A stalked discoid samara

with the brush-like stigma persistent on one side.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat

testal. Epidermis tanniniferous. Exotestal cells enlarged (wider than endo- and

mesotestal cells). Mesotesta often sclerotic. Endotesta subpalisade, with

lignified cell walls. Tegmen unspecialized. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm

copious, oily and proteinaceous. Embryo small, straight, little differentiated,

chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 14

DNA The plastid gene

rpl22 is perhaps absent from Euptelea. Nuclear gene

AP3 triplicated?

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin), cyanidin, chalcones, dihydrochalcones, and triterpene

saponins present. Myricetin, ellagic acid and cyanogenic compounds not

found.

Use Medicinal plants,

timber.

Systematics Euptelea (2;

E. pleiosperma: eastern Himalayas, Assam, southwestern and central

China; E. polyandra: Japan).

Euptelea is

sister to the remaining Ranunculales.

Tamura in Bot. Mag. (Tokyo) 85: 40. Mar 1972

Glaucidiales Takht.

ex Reveal in Novon 2: 238. 13 Oct 1992

Genera/species 1/1

Distribution Japan.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, perennial

herb.

Vegetative anatomyPhellogen?

Primary vascular tissue consisting of two irregularly concentric cylinders of

vascular bundles: one outer cylinder with smaller bundles and one inner

cylinder with larger bundles. Endodermis absent. Palisade mesophyll absent.

Rhizome with normal secondary lateral growth. Xylem not V-shaped in

cross-section. Vessel elements usually with simple (sometimes scalariform with

few bars or reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform or

pseudoscalariform (in reality alternate). Vessel restriction patterns

occurring. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements usually libriform fibres

(sometimes tracheids) with bordered pits. Wood rays multiseriate,

heterocellular? (with non-lignified cell walls). Axial parenchyma paratracheal,

pervasive or intervascular. Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes multilacunar with

several? leaf traces. Crystals absent?

Trichomes Hairs

unicellular?

Leaves Alternate (distichous),

simple, palmately lobed, with conduplicate, supervolute to curved and plicate

ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection

annular and medullary. Venation palmate. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticle wax

crystalloids as few small irregular platelets, dominated by nonacosan-10-ol.

Leaf margin serrate.

Inflorescence Flowers

terminal, usually solitary (rarely pairwise).

Flowers Actinomorphic.

Hypogyny. Tepals four, petaloid, decussate, caducous, free. Nectary absent.

Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens c. 350 to

more than 500, spiral, fasciculate. Filaments filiform, free from each other

and from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, extrorse?,

longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory? Staminodia

absent.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous? Pollen grains tricolpate, shed as monads,

bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum (with

reduced columellae), spinulate, punctate-perforate.

Gynoecium Carpels (one or) two

(to four), antesepalous, conduplicate-plicate, somewhat connate at base. Ovary

superior, unilocular (apocarpy; bilocular at base). Stylodia very short. Stigma

bifid, decurrent?, type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation marginal.

Ovules c. 15 to c. 20 (to more than 30) per carpel, anatropous, bitegmic,

usually tenuinucellar (rarely pseudocrassinucellar). Micropyle endostomal.

Outer integument seven to ten (to 13) cell layers thick, vascularized. Inner

integument three to five cell layers thick. Archespore usually ten- to

15-celled (megasporocytes). Primary parietal cell not formed. Nucellar cap c.

15 to c. 20 cell layers thick, massive, formed by periclinal divisions from

apical cells of megasporangial epidermis. Megagametophyte monosporous,

Polygonum type. Antipodal cells ephemeral or persistent (degenerating

immediately after fertilization or earlier), non-proliferating. Endosperm

development nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis unclassified type

(resembles onagrad). Polyembryony frequent.

Fruit Ventricidal and

dorsicidal follicles. Adaxial side of carpels expanding more than abaxial side

during fruit development, causing stigma to become inserted on ‘lower’

(abaxial) side at fruit maturation.

Seeds Aril absent. Seeds

flattened. Seed coat testal. Outer integument vascularized, developing into a

wing-like structure on testa. Inner integument degenerating. Tegmen collapsed?

Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, starchy? Embryo small, elongate,

well differentiated, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two, foliaceous, with more or less

connate petioles. Germination?

Cytology n = 10 –

Chromosomes 1,5–2,5 µm long, reniform, T type (Thalictrum type).

DNA Mitochondrial intron

coxII.i3 lost?

Phytochemistry Insufficiently

known. Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, rhamnocitrin) and glaupalol (a

furanocoumarin) present. Berberine and other alkaloids, and cyanogenic

compounds not found.

Use Ornamental plants.

Martinov, Tekhno-Bot. Slovar: 318. 3 Aug 1820

[’Hydrasteae’]

Hydrastidales Takht.,

Divers. Classif. Fl. Pl.: 98. 24 Apr 1997

Genera/species 1/1

Distribution Central and

eastern parts of temperate North America.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, perennial

herb. Roots and rhizome inside bright yellow due to presence of berberine.

Erect stem with swollen nodes.

Vegetative anatomyPhellogen?

Upright stem (not rhizome) multilacunar, with cortical vascular bundles.

Medullary bundles present. Primary vascular tissue amphicribral, consisting of

two irregularly concentric cylinders of vascular bundles: an outer cylinder

with smaller bundles and an inner cylinder with larger bundles. Endodermis

absent. Palisade mesophyll absent. Secondary lateral growth absent. Xylem not

V-shaped in cross-section. Vessel elements usually with simple (rarely

scalariform with a single bar, or reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits

scalariform, bordered pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform

fibres with bordered pits. Wood rays multiseriate, heterocellular? Axial

parenchyma paratracheal? Sieve tube plastids Ss type. Nodes multilacunar with

several leaf traces; lower leaves usually with 9-lacunar nodes, upper leaves

with 3–5-lacunar nodes. Crystals?

Trichomes Hairs absent?

Leaves Alternate (distichous,

usually one basal leaf and two stem leaves), simple, entire or usually

palmately lobed, with plicate ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole

base enclosing rhizome. Petiole vascular bundles eight to 24, radially arranged

(transection annular and medullary: medullary petiole bundles present).

Venation palmate. Palisade mesophyll absent. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax

crystalloids as few small irregular platelets, dominated by nonacosan-10-ol.

Leaf margin serrate to biserrate.

Inflorescence Flowers

terminal, solitary.

Flowers Actinomorphic.

Hypogyny. Tepals (two or) three (or four), petaloid, small, with imbricate

aestivation, early caducous. Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens c. 40 to c.

75, spiral, free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed,

non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, extrorse?, longicidal (dehiscing by

longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory, with binucleate cells. Staminodia

absent.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains tricolpate, shed as monads,

bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate

infratectum, striate-reticulate or striate (with complex layer of striae).

Gynoecium Carpels five to c.

15, spiral, conduplicate, ab initio free, later connate at base. Ovary

superior, unilocular (apocarpy). Stylodium very short. Stigma bifid, with

multicellular processes, type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation marginal.

Ovules one or two (sometimes three or four) per carpel, anatropous, bitegmic,

crassinucellar. Micropyle bistomal, Z-shaped (zig-zag). Outer integument four

to eight (to 13) cell layers thick. Inner integument two to four (or five) cell

layers thick. Integument two or more cell layers thick, non-vascularized.

Archespore probably unicellular. Hypostase absent. Nucellar cap approx. eight

to ten cell layers thick, formed by periclinal divisions from apical cells of

megasporangial epidermis. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type.

Antipodal cells non-modified, proliferating (dividing into five to nine

long-lived cells). Endosperm development nuclear. Endosperm haustoria?

Embryogenesis?

Fruit A multifolliculus

consisting of five to c. 15 usually one-seeded fleshy berry-like (drupaceous?)

follicles, dehiscing adaxially and abaxially (cf. Glaucidium with

follicle both dorsicidal and ventricidal).

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat

exotestal-exotegmic. Exotesta palisade, with very elongated cells,

multiplicative, accumulating dark-brown substance. Exotegmen lignified,

multiplicative. Remaining testal and tegmic cell layers parenchymatous and

collapsed. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, starchy? Embryo very

small, straight, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two. Germination?

Cytology n = 13 –

Chromosomes small, reniform, T type (Thalictrum type).

DNA Mitochondrial intron

coxII.i3 lost?

Phytochemistry Flavonols and

isoquinoline alkaloids (berberine, hydrastine etc.) present. Rhizome containing

a ribitole-like substance and benzylisoquinoline alkaloid compounds with

D-galactose. Cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Medicinal plant.

Systematics Hydrastis

(1; H. canadensis; northeastern United States, southeastern

Canada).

Hydrastis

may be sister to Glaucidium

(Glaucidiaceae), the

two species together forming a sister-group of Ranunculaceae. The cuticular

wax crystalloids in Hydrastis

are very similar to those occurring in Glaucidium.

Hydrastis has a special organization of those vascular strands that supply the

stamens (more or less fascicled, supplied from vascular bundles of the central

cylinder) and the carpels (each carpel supplied by four vascular bundles).

Brown in Trans. Linn. Soc. London 13: 212. 23

Mai-21 Jun 1821 [‘Lardizabaleae’], nom. cons.

Sargentodoxaceae

Stapf ex Hutch., Fam. Fl. Pl. 1: 100. 15 Jan 1926

[‘Sargentadoxaceae’], nom. cons.;

Decaisneaceae (Takht. ex H. N. Qin) Loconte in H.

Loconte, L. M. Campbell et D. W. Stevenson, Plant Syst. Evol. 9: 105. Dec 1995;

Lardizabalales Loconte in D. W. Taylor et L. J.

Hickey, Fl. Pl. Orig. Evol. Phylog.: 274. 21 Dec 1995;

Sinofranchetiaceae Doweld in Byull. Mosk. Obshch.

Ispyt. Prir., Biol. 105(5): 60. 9 Oct 2000;

Lardizabalineae Shipunov in A. Shipunov et J. L.

Reveal, Phytotaxa 16: 63. 4 Feb 2011

Genera/species 7/29–34

Distribution Southern and

eastern Himalayas, East Asia, Indochina, southern South America.

Fossils Seeds of

Sargentodoxa are known from the Miocene of North America, and seeds of

Akebia and Decaisnea have been found in Miocene layers in

Germany. Kajanthus lusitanicus was described from a late Aptian to

early Albian layer in western Portugal. It is a trimerous, radially

symmetrical, bisexual flower with several perianth whorls, six stamens in two

whorls, and three free carpels.

Habit Usually monoecious or

dioecious (in Decaisnea polygamomonoecious), usually climbing or

scrambling evergreen or deciduous shrubs or lianas (Decaisnea an

upright shrub).

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

ab initio usually superficial (in Sargentodoxa in innermost layer of

pericycle). Primary vascular tissue consisting of a cylinder of vascular

bundles. Primary medullary strands wide, usually lignified. Vessel elements

usually with simple (sometimes scalariform) perforation plates; lateral pits

usually alternate (in Decaisnea scalariform or transitional), usually

with bordered (in Decaisnea simple) pits. Imperforate tracheary

elements tracheids or fibre tracheids, usually with bordered pits (in

Holboellia and often also in Decaisnea simple pits), septate

or non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays usually multiseriate (in

Decaisnea usually uniseriate), homocellular or heterocellular. Axial

parenchyma apotracheal diffuse, paratracheal scanty vasicentric or banded, or

absent. Wood elements (particularly in secondary phloem) partially storied

(sometimes irregularly). Sieve tube plastids Ss type, very large. Phloem in

Sargentodoxa with tanniniferous secretory cells. Nodes 3:3, trilacunar

with three leaf traces. Medulla with sclerenchyma cells (not in

Decaisnea). Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals sometimes abundant. Wood

rays sometimes with rhomboidal crystals (Stauntonia).

Trichomes Hairs multicellular,

uniseriate, or absent.

Leaves Alternate (spiral),

usually palmately compound (in Decaisnea pinnately compound; in

Sargentodoxa sometimes simple), entire or lobate, with conduplicate

ptyxis; petiolules usually pulvinate at base. Stipules usually absent (present

in Lardizabala); leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle

transection arcuate. Venation usually palmate (in Decaisnea pinnate).

Stomata usually anomocytic (in some species of Stauntonia cyclocytic).

Cuticular wax crystalloids as clustered tubuli (Berberis type),

chemically dominated by nonacosan-10-ol. Mesophyll with calciumoxalate druses

or single prismatic crystals. Idioblasts with ethereal oils absent. Leaflet

margins entire or serrate with chloranthoid teeth.

Inflorescence Axillary,

panicle or raceme. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) present or absent.

Flowers Actinomorphic.

Hypogyny. Outer tepals (three to) 3+3 (to eight), with imbricate – or

outermost ones with valvate – aestivation, whorled, petaloid, free. Inner

tepals (nectariferous staminodia?) usually 3+3, whorled, petaloid (sometimes

absent). Nectaries present on apex of inner tepals (nectariferous staminodia?)

or stamens, or absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens (three to)

3+3 (to eight), antepetalous, alternisepalous, occasionally somewhat

foliaceous. Filaments free or connate into tube, free from tepals. Anthers

basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, extrorse or latrorse, longicidal

(dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective often elongated into prolonged

appendage; microsporangia often sunken into almost foliaceous wide connective.

Tapetum secretory, with usually binucleate (sometimes trinucleate or

quadrinucleate) cells. Female flowers usually with six staminodia.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tricolpate to

tricolporate (sometimes dicolpate to dicolporate, rarely syncolpate), shed as

monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with sparsely columellate or

almost acolumellate infratectum, reticulate, microreticulate, (micro)perforate,

punctate, foveolate, psilate, striate, or smooth.

Gynoecium Carpels usually

three or six to nine (to twelve) in one to five whorls of three (in

Sargentodoxa c. 50 to c. 90, spiral), free; carpel plicate,

postgenitally partially occluded, with open secretory canal; extragynoecial

compitum sometimes present. Ovary superior, unilocular (apocarpy). Stylodia

very short or absent. Stigma peltate, often oblique, hairy, non-papillate,

usually Wet type. Male flowers sometimes with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation usually

laminal or laminal-lateral (in Decaisnea submarginal, with ovules

along ventral line of fusion). Ovules usually numerous (sometimes few) per

carpel (in Sargentodoxa a single subapical pendulous ovule), usually

anatropous (in Boquila and Lardizabala hemitropous),

horizontal, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal. Outer integument

three to five cell layers thick. Inner integument two or three cell layers

thick. Parietal tissue approx. three cell layers thick. Megagametophyte

monosporous, Polygonum type. Antipodal cells usually not persistent.

Endosperm development ab initio cellular. Endosperm haustoria?

Embryogenesis?

Fruit An assemblage of fleshy

(with fleshy placenta) follicles (Akebia, species of

Decaisnea) or a berry with leathery pericarp. Fruit in

Decaisnea with laticifers.

Seeds Aril usually absent

(present in Akebia). Seed coat exotestal. Testa usually

multiplicative. Exotesta palisade. Mesotesta and endotesta unspecialized.

Tegmen unspecialized. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, oily

(sometimes, e.g. in Sargentodoxa, also starchy or with hemicellulose).

Embryo small, straight, well differentiated, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two.

Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 11

(Sargentodoxa), n = 14 (Lardizabala), n = 15

(Decaisnea), n = 16 (Akebia)

DNA The nuclear gene

AP3 is triplicated.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin), cyanidin, phenols, and triterpene saponins present.

Ellagic acid, alkaloids and cyanogenic compounds not found. Aluminium

accumulated in some species of Holboellia and Stauntonia.

Use Ornamental plants,

medicinal plants, fruits (Boquila, Lardizabala).

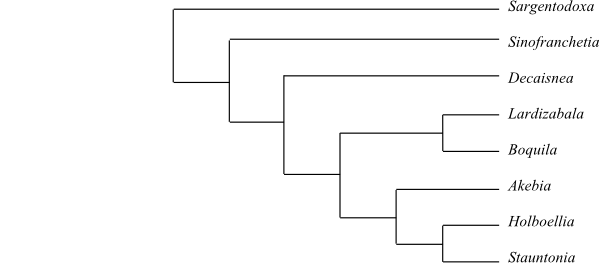

Systematics Lardizabalaceae are

sister-group to Circaeasteraceae.

Sargentodoxoideae

(Stapf ex Hutch.) Thorne et Reveal in Bot. Rev. (Lancaster) 73: 89. 29 Jun

2007

1/1. Sargentodoxa (1; S.

cuneata; China, Laos, Vietnam). – Usually dioecious (with few bisexual

flowers). Phellogen ab initio inner-pericyclic. Tanniniferous cells present.

Leaves trifoliolate. Outer tepals four to nine. Inner tepals five to seven.

Staminodia petaloid. Carpels c. 50 to c. 90, spiral, ascidiate. Ovule one per

carpel, pendulous. Outer integument approx. four cell layers thick. Placenta

fleshy in fruit. Testal surface unspecialized. n = 11. Triterpenoid saponins

not found.

Lardizabaloideae

Burnett, Outlines Bot.: 830. Feb 1835 [‘Lardizabalidae’]

6/28–33. Decaisnea

(1; D. insignis; eastern Himalayas to central China), Sinofranchetia

(1; S. chinensis; western and central China), Lardizabala (1;

L. funaria; central and southern Chile between the Andes and the

Pacific, southern Argentina), Boquila (1; B. trifoliolata;

central and southern Chile between the Andes and the Pacific, southern

Argentina), Akebia (4;

A. chingshuiensis, A. longeracemosa, A. quinata,

A. trifoliata; China, the Korean Peninsula, Japan, Taiwan),

Stauntonia (20–25; northeastern India, the Himalayas, China, the

Korean Peninsula, Japan, Taiwan). – Southern and eastern Himalayas, East

Asia, southern South America. Usually monoecious (rarely dioecious or

bisexual). Phellogen ab initio superficial. Vessel elements sometimes with

scalariform perforation plates. Stomata sometimes cyclocytic. Leaves sometimes

palmately compound or imparipinnate, with basal tooth or lobe. Venation

sometimes pinnate. Outer tepals sometimes three. Inner tepals sometimes absent.

Stamens sometimes three or eight. Filaments connate. Tapetum with up to

quadrinucleate cells. Pollen grains sometimes colporoidate, sometimes

tricellular at dispersal. Female flowers with staminodia. Carpels sometimes up

to twelve. Stigma sometimes peltate. Placentation sometimes laminar. Ovules

(few to) numerous per carpel, sometimes hemitropous. Outer integument three to

five cell layers thick. Inner integument two or three cell layers thick.

Parietal tissue approx. three cell layers thick. Antipodal cells in Decaisnea

persistent. Endosperm development usually cellular (in Decaisnea

nuclear). Fruit a berry or a fleshy follicle, often with fleshy placenta. Testa

multiplicative. Exotestal cells lignified, elongated (in Decaisnea),

or non-lignified and fibrous (in Akebia and

Stauntonia). Hypodermal cells thickened. Endosperm starchy or with

hemicellulose. n = 14–16, 17?, 18. Oleanone triterpenoid saponins present.

Aluminium accumulation occurs in Stauntonia, a synapomorphy of this

clade.

de Jussieu, Gen. Plant.: 284. 4 Aug 1789

[’Menisperma’], nom. cons.

Menispermales Juss.

ex Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 225. Jan-Apr 1820

[‘Menispermeae’]; Pseliaceae Raf., New

Fl. N. Amer. 4: 8. med 1838 [’Pselides’]

Genera/species 74/535–540

Distribution Tropical and

subtropical regions in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, and a few species

in temperate eastern North America and temperate East Asia.

Fossils The oldest fossil

consists of keeled endocarps of Prototinomiscium from the Turonian to

the Maastrichtian of Central Europe. Anamirta pfeifferi is fossilized

wood (probably of a liana) from the Maastrichtian Deccan Intertrappean Beds in

India. A large number of endocarps, which can be assigned to Menispermaceae, are known

from Cenozoic layers in Europe and North America.

Habit Dioecious, usually

evergreen lianas, or scrambling and climbing perennial herbs (rarely shrubs or

trees [Burasaia, Penianthus, Sphenocentrum]; one

species of Stephania an erect herb).

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

ab initio superficially or deeply seated. Secondary lateral growth usually

anomalous (particularly in lianas), from successive cambia. Vessel elements

with simple perforation plates; lateral pits alternate or scalariform, simple

and/or bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids or

libriform fibres with simple and/or bordered pits, non-septate (also

vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate, interfascicular, usually wide and

very tall (rarely narrow), homocellular or heterocellular, often lignified.

Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal

scanty vasicentric, scalariform or in short bands connecting successive layers

of vascular bundles. Wood elements often storied, especially in secondary

phloem. Intraxylary (concentric) phloem usually present. Sieve tube plastids Ss

type, very large. Nodes 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces. Stem and leaves

with rows of secretory cells. Parenchyma with numerous asterosclereids and

osteosclereids. Crystal sand present or absent. Raphid idioblasts (raphid

cells) present or absent. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals abundant. Wood rays

and axial parenchyma often with rhomboidal crystals.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or

multicellular, uniseriate.

Leaves Alternate (spiral),

usually simple (in Burasaia trifoliolate), entire or lobed (one

species of Cocculus with phyllocladia), often peltate, with ? ptyxis.

Stipules usually absent; leaf sheath absent. Petiole often with proximal and

distal pulvinus. Petiole vascular bundle transection annular. Venation palmate,

actinodromous or acrodromous, or pinnate. Stomata anomocytic, paracytic,

staurocytic or often more or less cyclocytic (sometimes actinocytic), often

surrounded by a rosette of subsidiary cells. Cuticular wax crystalloids as

clustered tubuli (Berberis type), chemically dominated by

nonacosan-10-ol. Domatia usually as pockets (rarely hair tufts). Epidermal

cells often with calciumoxalate crystals, sometimes with silica or trichome

hydathodes. Mesophyll with sclerenchymatous idioblasts and mucilage cells.

Idioblasts with ethereal oils absent. Laminar surface sometimes with ridges of

laticifers. Leaf margin usually entire (sometimes serrate or lobed).

Extrafloral nectaries present or absent.

Inflorescence Terminal or

axillary, raceme- or headlike, or compound panicle (flowers rarely solitary or

paired).

Flowers Usually actinomorphic

(female flowers in Antizoma, Cyclea, Cissampelos and

some species of Stephania slightly zygomorphic). Hypogyny. Tepals

usually whorled (sometimes spiral); in female flowers sometimes fewer than in

male flowers. Outer tepals (one to) six (to more than twelve), with imbricate

or valvate aestivation, sepaloid, usually in whorls each one with usually three

(rarely one), usually free (in Cyclea and Synclisia slightly

connate). Inner tepals (absent or one to) six (to eight), with usually

imbricate aestivation, petaloid, usually free (in Cyclea and some

species of Disciphania connate; rarely enclosing stamens). Nectary

absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens three, six,

twelve or more (in one species of Odontocarya one; in

Hypserpa up to c. 40), majority antepetalous, spiral or whorled.

Filaments free or more or less connate into synandrium, free from tepals.

Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (rarely

disporangiate), with superposed thecae, usually introrse (rarely extrorse),

usually longicidal (dehiscing by usually longitudinal [sometimes transversal]

slits). Tapetum secretory. Female flowers often with staminodia.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains (2–)3(–4)-colpate,

(2–)3(–4)-colporate (sometimes syncolporate), (2–)3(–4)-porate or

(2–)3(–4)-pororate (rarely cryptoporate or inaperturate), shed as monads,

bicellular at dispersal. Exine semitectate, with columellate infratectum,

reticulate or microreticulate.

Gynoecium Carpels usually

three, six or more (rarely one or two; in one species of Tiliacora and

one species of Triclisia c. 20 to 32), free or slightly connate at

base, often stipitate (on gynophore); carpel plicate (ascidiate?),

postgenitally partially fused, with open secretory canal. Ovary superior,

unilocular (apocarpy). Style very short or absent. Stigma entire, bifid or

trifid, expanded above, hairy to non-papillate, usually Dry (occasionally Wet)

type. Male flowers often with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation

ventral-marginal. Ovules usually two per carpel (one of which degenerating),

anatropous or campylotropous (often amphitropous after fertilization),

apotropous or epitropous, pendulous to horizontal (ascending?), unitegmic

(derived from integumentary shifting) or bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle

endostomal or bistomal, Z-shaped (zig-zag). Outer integument two to five cell

layers thick. Inner integument two cell layers thick (when one integument, then

three or four cell layers thick). Megagametophyte monosporous,

Polygonum type. Synergids sometimes with a filiform apparatus.

Antipodal cells multinucleate, often proliferating. Endosperm development ab

initio nuclear (finally cellular). Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis

onagrad.

Fruit An assemblage of

single-seeded stipitate drupes on a globose, discoid, columnar or branched

carpophore, often flattened or strongly curved (cf. the name

Menispermum = ’moon-seed’). Exocarp thin or leathery. Mesocarp

fleshy to fibrous, sometimes sclerified. Endocarp sclerified, hard, usually

sculptured in different ways, usually with a condyle (placentary outgrowth or

invagination; sometimes absent; condyle produced during ovary development due

to intruding ovary wall on placenta, causing seed to curve).

Seeds Aril absent. Seed

usually curved. Testa little differentiated (sometimes absent). Exotesta

sometimes tabular, lignified. Mesotesta and endotesta unspecialized. Tegmen

unspecialized. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm usually copious (sometimes

partially or entirely ruminate; absent in most genera in cladogram 2), oily.

Embryo small to large, straight or curved, chlorophyll? Cotyledons usually two

(rarely one), flat or terete, often fleshy (genera in cladogram 2). Germination

phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = (9-)11-13 –

Polyploidy (tetraploids, hexaploids) occurring.

DNA The nuclear gene

AP3 is triplicated.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol), flavones, diterpenoids, sesquiterpenoids, tannins,

benzylisoquinoline and aporphine alkaloids (benzyltetrahydroisoquinoline and

aporphine derivatives in dimeric form, e.g. berberine, morphinane), hasubanane

alkaloids (protostephanines, erythrinanes, cocculolidines, morphines,

quettamine-morphine dimers, hasubanonines, acutumines, etc.), azafluoranthene

alkaloids, tropoloisoquinoline alkaloids, tubocurarine chloride (a curare

mixture of alkaloids), toxic sesquiterpene lactones, phenylic cinnamide,

furofuran lignans, and frequent cyanogenic compounds present. Tyrosine-derived

cyanogenic glycosides and caffeic acid rare. Ellagic acid and proanthocyanidins

not found.

Use Ornamental plants,

medicinal plants (Anamirta cocculus, Chondrodendron

tomentosum, Jateorhiza palmata etc), fish- and arrow poisons

(curare from Chondrodendron, Curarea, Sciadotenia

etc., coccel kernels and picrotoxine from Anamirta), timber.

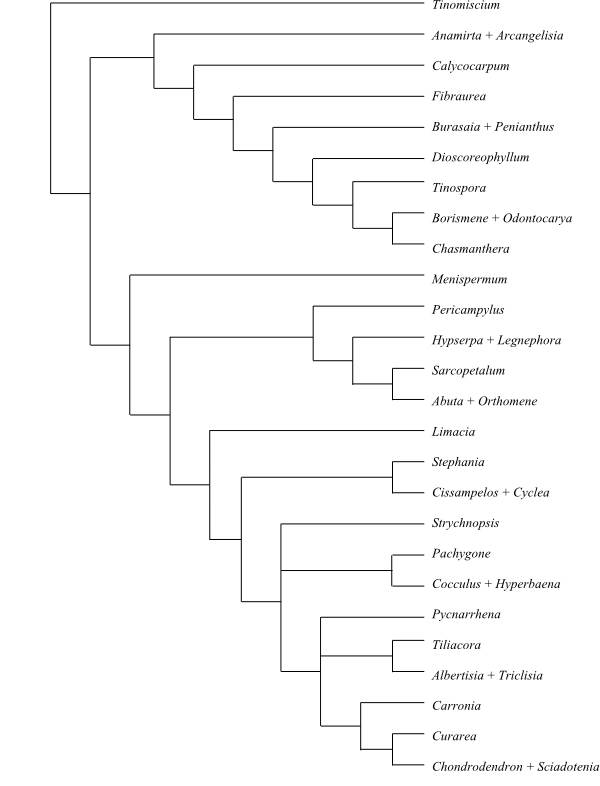

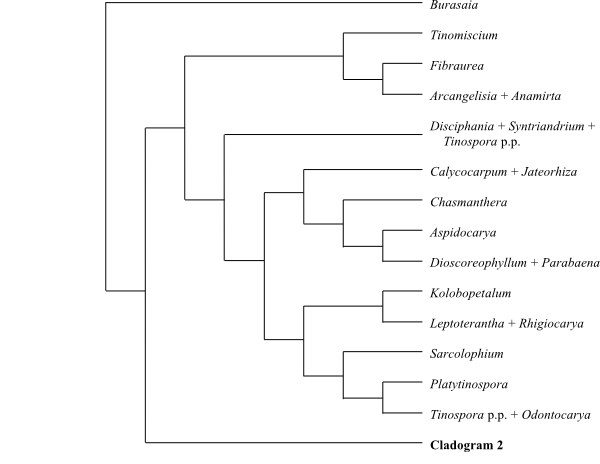

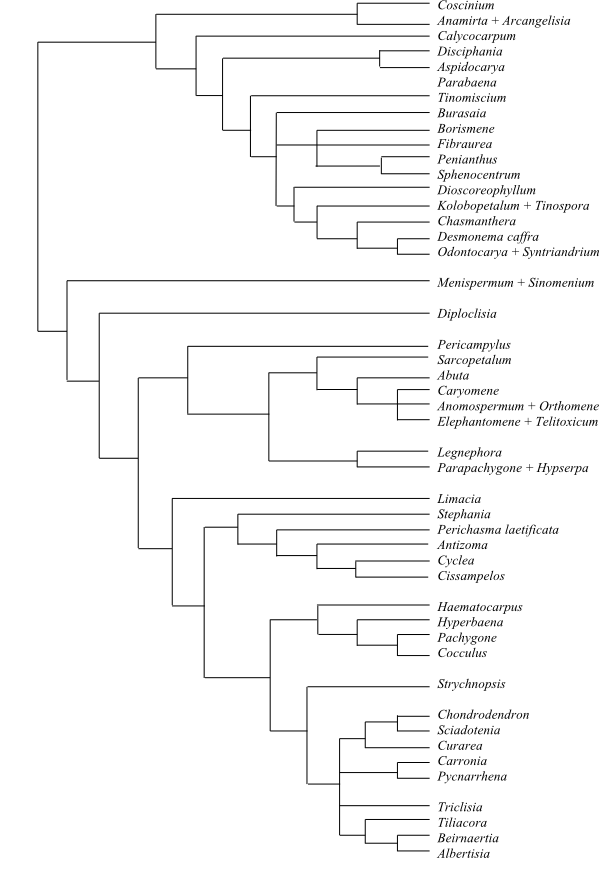

Systematics Menispermaceae are

sister-group to the clade [Berberidaceae+[Ranunculaceae+ [Hydrastis+Glaucidium]]].

Burasaia was sister to the remaining

Menispermaceae,

according to analyses of morphological data by Jacques & Bertolino (2008).

Ortiz & al. (2007), using ndhF sequence data, recovered

Tinomiscium sister to the remainder. Hoot & al. (2009), using

atpB and rbcL sequence data, identified a clade comprising

Menispermum and Sinomenium as sister to the rest with low to

moderate support, and Burasaia was nested deep inside Menispermaceae. On the other

hand, adding ndhF data rendered Tinomiscium again sister to

the rest and Menispermum was nested deep within Menispermaceae.

Chasmantheroideae are sister-group to Menispermoideae (Ortiz

& al. 2016). The taxonomy below follows Ortiz & al. (2016).

Chasmantheroideae

Luerss., Handb. Syst. Bot. 2: 574. Nov 1880

29/>156. Pantropical. Tangential cell

walls of wood rays in Tinomiscium oblique to ray axis in

cross-section. Leaf surface sometimes (e.g. in Fibraurea and

Tinomiscium) with laticifers as fine ridges. Seed subglobose to

reniform, ruminate. Embryo spathuliform. Cotyledons foliaceous, more or less

divaricate.

Coscinieae Hook. f. et

Thomson, Flora Ind.: 177. 1855

3/6. Coscinium (2; C.

blumeanum, C. fenestratum; India, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, West

Malesia to Borneo), Anamirta (1; A. cocculus; India,

Southeast Asia, Malesia to Timor), Arcangelisia (3; A. flava,

A. gusanlung, A. tympanopoda; Southeast Asia, Malesia to New

Guinea). – Tropical Asia. Sepals in three worls. Petals absent. Filaments

more or less connate. Drupelet with remnant of style/stigma subapical-adaxial.

Endocarp and seed subglobose.

Burasaieae Endl., Gen.

Plant. Suppl. 5: 25. 1850

26/>150. Calycocarpum (1;

C. lyonii; eastern North America); Parabaena (6; P.

denudata, P. echinocarpa, P. elmeri, P.

megalocarpa, P. sagittata, P. tuberculata; Southeast

Asia, Malesia), Aspidocarya (1; A. uvifera; northeastern

India to southwestern China), Disciphania (c 25; Mexico, Central

America, tropical South America); Tinomiscium (1; T.

petiolare; Southeast Asia, Malesia), Fibraurea (3; F.

darshanii: India; F. recisa: southern China, Indochina; F.

tinctoria: India, Assam, Southeast Asia, the Philippines, Borneo,

Sulawesi), Borismene (1; B. japurensis; tropical South

America), Paratinospora (2; P. dentata: Taiwan; P.

sagittata: China), ‘Penianthus’ (4; P.

camerounensis, P. longifolius, P. patulinervis, P.

zenkeri; tropical West and Central Africa; non-monophyletic),

Sphenocentrum (1; S. jollyanum; tropical West Africa),

Burasaia (4; B. australis, B. congesta, B.

gracilis, B. madagascariensis; Madagascar), Orthogynium

(1; O. gomphloides; Madagascar?), Dioscoreophyllum (3; D.

cumminsii, D. gossweileri, D. volkensii; tropical

Africa), Jateorhiza (2; J. macrantha, J. palmata;

tropical Africa), ’Tinospora’ (36; tropical Asia, tropical

Australia; polyphyletic), Kolobopetalum (4; K. auriculatum,

K. chevalieri, K. leonense, K. ovatum; tropical

Africa), Rhigiocarya (2; R. peltata, R. racemifera;

tropical West and Central Africa), Hyalosepalum (>10; tropical

Africa), Sarcolophium (1; S. tuberosum; tropical Africa),

Chasmanthera (2; C. dependens: tropical Africa; C.

welwithschii: Congo), Leptoterantha (1; L. mayumbense;

tropical Africa), Syntriandrium (1; S. preussii; tropical

West and Central Africa), Dialytheca (1; D. gossweileri;

Angola), Odontocarya (36; southern Mexico, Central America, tropical

South America). – Unplaced Burasaieae

Chlaenandra (1; C. ovata; New Guinea),

Platytinospora (1; P. buchholzii; tropical West and Central

Africa). – Pantropical, one genus, Calycocarpum, in eastern North America.

Ovules anatropous. Endocarp and seed straight. Seed abaxially-adaxially

compressed, naviculiform. Calycocarpum is sister to the remaining Burasaieae

(e.g. Wang & al. 2017).

Menispermoideae Arn.

in R. Wight et G. A. W. Arnott, Prodr. Fl. Ind. Orient.: 11. 10 Oct 1834

[’Menispermeae’]

45/380–385. Pantropical, few species

in temperate regions. Style lateral to basal. Drupelet with remnant of

style/stigma subbasal to basal. Endocarp laterally compressed, usually curved

(in Orthomene straight), often sculptured. Seed curved, usually not ruminate.

Endosperm sometimes absent. Embryo curved, strap-shaped. Cotyledons fleshy,

cylindrical, adpressed. – Menispermeae are sister-group to the

remaining Menispermoideae and Anomospermeae successive

sister-group to the rest. – Ortiz & al. (2016) found the following

topology:

[Menispermeae+[Anomospermeae+[Limacieae+[Tiliacoreae+[Pachygoneae+[Spirospermeae+Cissampelideae]]]]]]

Menispermeae DC.,

Syst. Nat. 1: 510, 511. 1-15 Nov 1817 [’Menispermeae verae’]

2/3. Menispermum (2; M.

dauricum: East Asia; M. canadense: southeastern Canada, eastern

United States), Sinomenium (1; S. acutum; central China,

Japan). – East Asia, eastern North America. Stamens free, numerous. Endocarp

longitudinally and transversally ridged. Seed semiannular-crescentic.

Anomospermeae Miers in

Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist., ser. 2, 7: 36. Jan 1851

13/c 80. Diploclisia (2; D.

affinis: China; D. glaucescens: India, Sri Lanka, Burma, southern

China, Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea), Sarcopetalum (1; S.

harveyanum; southern New Guinea, eastern Queensland, eastern New South

Wales, eastern Victoria), Legnephora (5; L. acuta, L.

microcarpa, L. minutiflora, L. moorei, L.

philippinensis; New Guinea, eastern Queensland), Parapachygone

(1; P. longifolia; northeastern Queensland), Hypserpa (10;

Southeast Asia, Malesia to Polynesia), Pericampylus (3; P.

glaucus, P. incanus, P. macrophyllus; China, Taiwan,

tropical Asia from India to Malesia), Echinostephia (1; E.

aculeata; southeastern Queensland, northeastern New South Wales);

’Anomospermum’ (8; tropical America; polyphyletic),

Caryomene (5; C. foveolata, C. glaucescens, C.

grandifolia, C. olivascens, C. prumnoides; tropical

America), ’Orthomene’ (4; O. hirsuta, O.

prancei, O. schomburgkii, O. verruculosa; tropical

America; non-monophyletic), Elephantomene (1; E. eburnea;

northeastern South America), Telitoxicum (8; tropical South America),