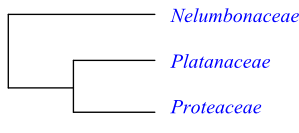

Phylogeny of Proteales based on DNA sequence data.

[Sabiaceae+Proteales+[Trochodendrales+[Didymelales+Gunneridae]]]

Proteanae Takht., Sist. Filog. Cvetk. Rast. [Syst. Phylog. Magnolioph.]: 401. 4 Feb 1967

Habit Usually bisexual (sometimes monoecious, andromonoecious or dioecious), evergreen trees or usually shrubs (rarely perennial rhizomatous herbs, some species with lignotuber). The majority are xerophytes. A few species are aquatic.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza often absent. Phellogen usually ab initio superficial (rarely deep or absent). Secondary lateral growth usually normal (rarely absent). Vessel elements usually with simple (sometimes scalariform or reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform, alternate or opposite, simple or bordered pits. Vestured pits sometimes present. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids, fibre tracheids or libriform fibres with simple and/or bordered pits, septate or non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, usually homocellular (sometimes heterocellular; rarely absent). Axial parenchyma usually paratracheal scanty, vasicentric, aliform, lozenge-aliform, winged-aliform, confluent, scalariform, unilateral, or banded (sometimes apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates; rarely absent). Sieve tube plastids S type (rarely Ss type). Nodes usually 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces (sometimes 1:1, 5:5 or 7:7). Secretory cavities absent. Tanniniferous cells often abundant. Heartwood with gum-like substances. Sclereids usually numerous. Silica bodies present in some species. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals sometimes present.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular (usually tricellular), uniseriate and thick-walled, basal cell being sunken into epidermis, stalk cell short and terminal cell long and sometimes split (rarely candelabra-shaped, dendritic or almost stellate), or absent; glandular hairs rare.

Leaves Usually alternate (spiral or rarely distichous; sometimes opposite or verticillate), simple or pinnately compound (sometimes twice or several times), usually entire or pinnately lobed (rarely palmate or palmately compound), usually xeromorphic (thick, coriaceous, ericoid or hair-like), with usually conduplicate (sometimes plicate) ptyxis. Stipules usually absent (rarely pairwise or single, sheathing, with ocreate base); leaf sheath usually absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection at least sometimes annular. Venation usually pinnate, brochidodromous (rarely parallellodromous or palmate), or leaves one-veined. Stomata usually (brachy)paracytic (rarely anomocytic or laterocytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids as clustered tubuli (Berberis type), chemically usually dominated by secondary alcohol nonacosan-10-ol (in Nelumbo -4-10- or -5-10-diols). Secretory cavities usually absent (rarely with laticifers). Mesophyll usually with sclerenchymatous idioblasts (with asterosclereids, columellar or palisade sclereids). Idioblasts with ethereal oils absent. Leaf margin serrate (sometimes serrate-dentate), crenate or entire.

Inflorescence Flowers solitary or pairwise, usually in terminal or axillary spike-, spadix-, cone-, or head-like, or compound inflorescence (flowers rarely solitary axillary or in compact multiflorous globular inflorescence). Numerous species with pseudanthia surrounded by showy involucral bracts.

Flowers Usually zygomorphic (rarely actinomorphic or asymmetric). Hypanthium present or absent. Hypogyny or half epigyny. Sepals (three or) four (to seven), free, with valvate aestivation, usually petaloid, free or connate into tube (tepals rarely numerous, with imbricate aestivation, outer ones sepaloid, inner ones petaloid, spiral). Small, almost spiny, abaxial projection present immediately below sepal apex. Petals probably absent; in their place (two to) four hypogynous alternisepalous scales or glands (= rudimentary petals?), free or connate into annular extrastaminal nectariferous disc (nectary and disc absent in some species).

Androecium Stamens (three or) four (to more than 400), usually whorled (rarely spiral), haplostemonous, antesepalous. Filaments usually free, entirely or in part adnate to sepals (episepalous, sometimes free from tepals; rarely absent). Anthers usually free, basifixed, non-versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (sometimes disporangiate), usually introrse (rarely latrorse or extrorse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory. Staminodia usually absent (female flowers sometimes with three or four staminodia).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually triporate (sometimes di- to octoporate, or di- to octocolporate; rarely di- to octocolpate, tricolpoidate, rugate, monocolpate or spiraperturate), shed as monads, usually bicellular (rarely tricellular) at dispersal. Apertures arranged according to Garside’s rule. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, reticulate, perforate or rugulate, scabrate or echinate.

Gynoecium Pistil usually composed of a single, entirely or partially closed carpel, usually with gynophore; carpel usually plicate (rarely ascidiate with margins seemingly occluded by secretion), postgenitally entirely fused, without canal (carpels rarely two to c. 40, whorled, free). Ovary superior or semi-inferior, usually monocarpellate and unilocular. Stylodium usually single (rarely absent or three to nine), usually with apex expanded around stigma and specialized for secondary pollen presentation. Stigma usually terminal, subterminal or lateral (stigmas rarely decurrent on adaxial side of each stylodium), usually papillate, Dry (rarely Wet) type. Pistillodium usually absent (male flowers rarely with pistillodium).

Ovules Placentation marginal eller subapical (rarely apical or ventral). Ovules one to three (to more than 100) per carpel, usually hemitropous (sometimes anatropous, amphitropous or orthotropous), pendulous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle usually endostomal. Inner integument usually thicker than outer integument (not in Nelumbo). Nucellar cap sometimes present. Megagametophyte Polygonum type. Synergids usually with a filiform apparatus. Endosperm formation ab initio nuclear, later usually entirely or partially cellular. Endosperm haustorium chalazal. Embryogenesis usually asterad (rarely solanad).

Fruit A follicle, capsule, achene or drupe, often fused into a cone-shaped syncarp (often lignified and long persistent). Pericarp and integument sometimes fused into a caryopsoid fruit.

Seeds Aril absent. Elaiosome present in some species. Seed coat usually testal. Testa sometimes multiplicative, occasionally thin. Exotesta sometimes palisade. Endotesta often palisade. Exotegmen often fibrous. Endotegmen unspecialized. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm usually absent (sometimes rudimentary, oily and proteinaceous). Embryo large, elongate, straight, oily and proteinaceous (starch absent), well differentiated, with or without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two (to nine). Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = 5, 7–21, 26, 28

DNA Nuclear gene paleoAP3 present.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), flavonol derivatives, cyanidin, condensed tannins, proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins), tropane alkaloids (bellendine, methylbellendine, benzoyltropine, benzoyltropane, 2α-benzoyltropane and phenylhydroxymethyl tropane), saponins, sapogenins, naphthoquinones, benzoquinones (rapanone, arbutin), tyrosine-derived cyanogenic glycosides (dhurrin, proteacin, taxiphyllin, triglochinin), and quebrachitol present. Ellagitannins, benzylisoquinoline alkaloids and aporphine alkaloids rare. Ellagic acid not found.

Systematics Proteales are sister-group either to Sabiaceae or to the remaining Tricolpatae minus Ranunculales and Sabiaceae.

Nelumbo is sister to [Platanus+Proteaceae]. Potential synapomorphies of this clade are, according to Stevens (2001 onwards): woody habit; wood rays at least 8-seriate; stomata laterocytic; flowers tetramerous; stamens equalling tepals, antetepalous; carpels with five vascular bundles, hairy, with complete postgenital fusion; stylodium long; ovules orthotropous; inner integument three to five cell layers thick; endosperm development nuclear; presence of myricetin and non-hydrolyzable tannins; and absence of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids.

|

Phylogeny of Proteales based on DNA sequence data. |

NELUMBONACEAE A. Rich. |

( Back to Proteales ) |

Nelumbonales Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin 1(1): 1. 1823 [‘Nelumbiaceae’]; Nelumbonopsida Endl., Gen. Plant.: 898. Nov 1839 [’Nelumbia’]; Nelumbonanae Takht. ex Reveal in Novon 2: 236. 13 Oct 1992; Nelumbonidae Takht., Divers. Classif. Fl. Pl.: 83. 24 Apr 1997; Nelumbonineae Shipunov in A. Shipunov et J. L. Reveal in Phytotaxa 16: 64. 4 Feb 2011

Genera/species 1/2

Distribution East, South and Southeast Asia, Malesia southeastwards to northern Australia, eastern North America to the West Indies and Colombia.

Fossils Fossil vegetative and reproductive structures are known from the Albian of Virginia and from the Campanian to the Maastrichtian of Argentina, and also from Cenozoic localities in the Northern Hemisphere. Peltate leaves have been described under Nelumbo and the similar extinct Nelumbites. Exnelumbites, in the form of leaf macrofossils with glandular chloranthoid teeth and lacking secondary venation, was described from the Campanian-Maastrichtian of Mexico and New Mexico.

Habit Bisexual, perennial herbs. Aquatic. Rhizome rich in starch. Internodes near growth points forming fleshy banana-shaped nutrient-storing tubers.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza absent. Main root ephemeral and replaced by adventitious roots from nodes. Rhizome with scale-like cataphylls and normal photosynthesizing leaves. Foliar primordia developing in groups of three: one sheathing fleshy scale-like cataphyll enclosing stem (perhaps representing a foliar stipule; at first enclosing apical bud) on lower side of rhizome; one scale-like cataphyll (enclosing petiole base of normal leaf); and one normal leaf on upper side of rhizome. Floral primordium developing in axil of second scale-like cataphyll. Rhizome branch developing in axil of normal leaf. Prophyll adaxial, on axillary branches on same side as first scale-like cataphyll. Phellogen absent? Primary vascular tissue as scattered bundles (atactostele?), without fibrous envelope. Endodermis present. Vessels (protoxylem lacunae?) present in root and rhizome metaxylem. Secondary lateral growth and cambium absent. Primary vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform, simple pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids with simple? pits. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids Ss type, with approx. ten starch grains unequal in size. Non-dispersive tubular and rod-shaped protein bodies present in sieve elements. Nodes? Parenchyma and vascular tissue with articulated laticifers as thin-walled elongate cells. Sclerenchymatous sclereids absent. Calciumoxalate as single (prismatic?) crystals.

Trichomes Hairs absent.

Leaves Alternate (in groups of three along stem, distichous), simple, entire, peltate or sunken, lanceolate, with involute ptyxis. Stipule single, intrapetiolar, sheathing, with ocreate base, open on leaf-opposite side of stem. Petiole up to c. 2 m long, echinate. Petiole vascular bundle transection? Lamina peltate, concave, up to one metre in diameter, usually with central disc responsible for air exchange for petiole canals. Venation palmate, actinodromous; main veins dichotomous, reaching leaf margin. Stomata anomocytic, restricted to adaxial side of leaf (on central disc). Cuticular wax crystalloids as clustered tubuli (Berberis type), chemically dominated by nonacosan-4-10-diol or nonacosan-5-10-diol. Lamina with secretory cavities (laticifers) with latex. Mesophyll without sclerenchymatous idioblasts. Idioblasts with ethereal oils absent. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Flowers axillary, solitary. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) absent.

Flowers Actinomorphic, large. Receptacle massive, with epidermal sharp-pointed calciumoxalate druses. Pedicel up to c. 2 m long. Hypogyny. Tepals numerous; outermost two to five (to eight) tepals sepaloid, with imbricate aestivation, inserted in vertical plane, caducous; inner c. 10 to c. 30 tepals petaloid, with imbricate aestivation, spiral, caducous, free. Nectary absent? Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens c. 100 to c. 300 (to more than 400), spiral (developing from annular meristem). Filaments elongate, free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, outer stamens extrorse, inner stamens extrorse, introrse or latrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective with claw-shaped apical appendage. Tapetum secretory, with multinucleate cells. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tricolpate (rarely monocolpate, dicolpate or spiraperturate), shed as monads, tricellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum, rugulate to (micro)perforate, with supratectal processes of various shape.

Gynoecium Carpels (two to) ten to c. 30 (to c. 40), in two to four whorls, free, obconical, fleshy or spongy, sunken into cavities on upper side of receptacle; carpel ascidiate (secondarily), (seemingly) occluded by secretion. Closure by transverse slit occurring together with longitudinal slit. Ovary superior, unilocular (apocarpy). Stylodia absent. Pollen canal central, with elongated papillae. Stigma annularly expanded, papillate, Wet type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation ventral to apical (or marginal to apical or laminar-dorsal). Ovule usually one (rarely two) per carpel, anatropous, pendulous, apotropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal. Outer integument c. 30 cell layers thick. Inner integument eight to ten cell layers thick. Funicular obturator present. Hypostase present. Parietal tissue three to five cell layers thick. Nucellar cap approx. four cell layers thick. Chalaza massive (ovule pachychalazal). Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Antipodal cells persistent, proliferating, multinucleate. Endosperm development ab initio cellular? (or helobial? or nuclear?). Endosperm haustorium? chalazal. Embryogenesis solanad (asterad?).

Fruit Hard-walled nuts sunken into dry hard receptacle. Nut with apical pore close to stigmatic remnants. Endocarp fused with seed coat. Pericarp with high concentrations of galactose, mannose and tannins.

Seeds Aril absent. Seeds pachychalazal? Testa thin, indistinct. Mesotesta and endotesta unspecialized. Tegmen unspecialized. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm rudimentary or absent. Embryo large, with chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, fleshy, connate and sheathing into a stipule-like tube surrounding plumule. Radicula ephemeral. Seeds very long-lived (sometimes germinative after at least several hundred years). Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 8 (16?)

DNA Nuclear gene paleoAP3 present.

Phytochemistry Flavonols, flavones, tannins, proanthocyanidins, aporphine and benzylisoquinoline alkaloids (benzoyltetrahydroisoquinoline aporphine, proaporphine, bis-benzoyltetrahydroisoquinoline bases, roemerine, annonaine, liriodenine etc.) present. Ellagic acid, cyanogenic compounds and saponins not found.

Use Ornamental plants, fruits (nut with edible embryo), vegetables. The lotus flower is an important symbol in several oriental religions (‘the Sacred Lotus’).

Systematics Nelumbo (2; N. lutea: eastern United States, Mexico, the Great Antilles, Honduras, Colombia; N. nucifera: East, South and Southeast Asia, Malesia to northern Australia).

Nelumbo is sister to [Platanus+Proteaceae] with moderate bootstrap support.

PLATANACEAE T. Lestib. |

( Back to Proteales ) |

Platanales T. Lestib. in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp. Regn. Veg.: 12. Sep-Oct 1835 [’Plataneae’]; Platanineae J. Presl in Nowočeská Bibl.. [Wšobecný Rostl.] 7: 1359 [‘1258’], 1379. 1846

Genera/species 1/10

Distribution Southeastern Canada to southern Mexico, the Balkan Peninsula, northeastern Mediterranean to western Himalayas, northern Indochina.

Fossils Fossil leaves (simple or palmately to pinnately compound) and reproductive structures of Platanaceae are known from numerous sites in the Northern Hemisphere from the Albian onwards. Fossil leaf taxa include Araliopsoides, Credneria pro parte, Erlingdorfia, Platanites and Tasymia. Aquia brookensis and Friisicarpus brookensis comprise male flowers and infructescences, respectively, from the Albian of Virginia. Hamatia elkneckensis and Friisicarpus elkneckensis are male inflorescences with tricolporate pollen and female flowers and fruits, respectively, from the Early Cenomanian of Maryland. ‘Platananthus’, from the mid-Cretaceous to the Cenozoic of Europe and North America, is represented by male inflorescences bearing flowers with distinct tepals. Quadriplatanus georgianus comprises male and female inflorescences from the Coniacian of Georgia in the United States; the male flowers have four tepals connate at the base; the female flowers bear one outer and one inner whorl of four tepals, the outer whorl being connate into a tube; the eight uniovular carpels are free. Archaranthus krassilovii is a male inflorescence with prominent tepals from the Maastrichtian to the Paleocene of eastern Siberia. Many early Platanaceae were probably insect-pollinated. The diversity and distribution of Platanaceae seem to have reached their peak during the Late Cretaceous and the Palaeogene.

Habit Monoecious, deciduous trees. Bark often exfoliating.

Vegetative anatomy Endomycorrhiza present in at least some species. Phellogen ab initio superficial (later in outer cortex). Vessel elements with scalariform and simple perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, scalariform and/or opposite, simple or bordered pits. Vestured pits present. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids with simple and bordered pits, septate or non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma absent or very rare (apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal scanty vasicentric, aliform, confluent, unilateral, or banded). Wood partially storied. Tile cells present. Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes 7:7, multilacunar with seven leaf traces. Parenchyma with oil cells. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals often abundant.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, simple or branched, candelabra-shaped, sometimes dendritic or almost stellate; glandular hairs with unicellular globular head present.

Leaves Alternate (usually distichous, sometimes spiral), simple, usually palmately lobed (in Platanus kerrii entire), with plicate ptyxis. Stipules usually pairwise connate, often foliaceous (in Platanus kerrii membranous) and adaxially sheathing (often into tube), usually closed (sometimes open), with ocreate base, early caducous. Axillary bud usually enclosed by petiole base (not in Platanus kerrii). Petiole vascular bundle transection annular, with wing bundles. Venation usually palmate (in Platanus kerrii pinnate); two large secondary veins arising from near leaf base; veins of higher order (tertiary etc.) approaching but not penetrating teeth. Stomata laterocytic or anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids as clustered tubuli (Berberis type), chemically dominated by nonacosan-10-ol. Domatia as pockets in vein axils on lower side of lamina. Idioblasts with ethereal oils absent. Leaf margin usually serrate, with platanoid teeth (glandular with apical cavity; rarely entire).

Inflorescence Axillary, with flowers in one to twelve dense, globular, many-flowered, short-stalked or unstalked partial inflorescences (compact panicles?) on a long pendant common peduncle, each floral head with a single basal circular bract.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Hypogyny. Outer tepals three or four (to seven), with valvate aestivation, free or connate at base; odd outer tepal abaxial. Inner tepals usually absent from female flowers (sometimes three or four, rudimentary), in male flowers three or four (to seven), rudimentary, free. Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens three or four (to seven), antesepalous. Filaments short or absent, free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, latrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective expanded into almost peltate terminal appendage. Tapetum probably secretory. Ring of fleshy structures present, possibly representing outer whorl of stamens (‘ridged staminodia’). Female flowers often with three or four staminodia.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains tri- or tetracolpate or (hexa)rugate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine semitectate, with columellate infratectum, reticulate.

Gynoecium Carpels (three to) five to eight (or nine), in two (or three) whorls, free; carpel plicate, postgenitally entirely fused, without canal. Ovary superior, unilocular (apocarpy). Stylodia narrowly elongated. Stigmas decurrent in two crests on adaxial side of stylodium, papillate, Dry type. Male flowers often with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation apical to marginal. Ovule usually one (sometimes two) per carpel, (semi)orthotropous, pendulous, apotropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal? Outer integument three or four cell layers thick. Inner integument approx. five cell layers thick. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type? Antipodal cells persistent. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A globular assemblage (syncarp) of one-seeded achenes, with long hairs at base (fruit rarely follicular).

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat testal. Testa thin, with hypodermal layer of thickened cells. Mesotesta cells sclerotic. Endotesta unspecialized. Tegmen unspecialized, early disappearing. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm sparse, proteinaceous, oily and with hemicellulose. Embryo large, narrow, straight, well differentiated, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = (7?–)16–21

DNA Nuclear gene paleoAP3 present.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), proanthocyanidins (cyanidin, prodelphinidin), and tyrosine derived cyanogenic glycosides (dhurrin, triglochinin) present. Alkaloids, saponins and ellagic acid not found.

Use Ornamental plants, carpentries.

Systematics Platanus (10; southeastern Canada, southwestern and eastern United States, Mexico, the Balkan Peninsula, northeastern Mediterranean to western Himalayas, with their highest diversity in Mexico; one species, Platanus kerrii, in northern Indochina).

Platanus is sister to Proteaceae.

PROTEACEAE Juss. |

( Back to Proteales ) |

Banksiaceae Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 235. Jan-Apr 1820 [’Banksiae’]; Proteopsida Bartl., Ord. Nat. Plant.: 91, 110. Sep 1830 [’Proteinae’]; Lepidocarpaceae Schultz Sch., Nat. Syst. Pflanzenr.: 374. 30 Jan-10 Feb 1832; Proteineae Reveal in Kew Bull. 66: 47. Mar 2011

Genera/species c 80/c 1.700

Distribution Africa south of Sahara, Madagascar, southern India and Sri Lanka to eastern China, Taiwan, southern Japan, Indochina, Malesia, islands in the southwestern Pacific, Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand, South and Central America; with their largest diversity in Mediterranean climates in Australia and South Africa.

Fossils Fossils of Proteaceae include wood, leaves, reproductive structures and especially pollen grains from the Santonian of Australia onwards. They have been found in all larger Gondwana fragments, and Late Cretaceous fossils are known also from the Antarctic Peninsula and New Zealand. Macrofossils occur from the Paleocene and the Eocene and include fossilized leaves of Banksieaeformis and Banksieaephyllum and the inflorescence of Musgraveinanthus alcoensis. Reports of Proteaceae fossils from the Northern Hemisphere are questionable.

Habit Usually bisexual (sometimes monoecious, andromonoecious or dioecious), evergreen trees or usually shrubs (rarely perennial rhizomatous herbs, some species with lignotuber). Most species are xerophytic.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza usually absent. Roots with four to seven protoxylem poles, usually with dense bundles of special short superficial lateral roots – proteoid roots, cluster roots – with limited growth (apical meristem aborting), produced at low phosphate supply. Phellogen usually ab initio superficial (rarely deeply seated). Primary medullary rays alternately wide and narrow. Vessel elements usually with simple (rarely scalariform or reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform, alternate or opposite, bordered pits. Vestured pits present at least in Persoonia. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids, fibre tracheids or libriform fibres (sometimes very long) with simple and/or bordered pits, septate or non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular. Axial parenchyma usually paratracheal scanty, aliform, lozenge-aliform, winged-aliform, confluent, scalariform, vasicentric, unilateral, or banded (rarely apotracheal banded with most bands independent of vessels). Secondary phloem often stratified into hard fibrous and/or sclerenchymatous layers, and soft parenchymatous layers; sieve tubes with sieve surfaces along most of their length. Sieve tube plastids S type (or P type?). Nodes usually 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces (sometimes 1:1, unilacunar with one trace; in Finschia trilacunar with three or more traces). Secretory cavities absent. Tanniniferous cells often abundant. Heartwood with resin-like substances. Sclereids abundant. Silica bodies present in some species. Crystals?

Trichomes Hairs tricellular, uniseriate and thick-walled, with basal cell sunken into epidermis, stalk cell short and terminal cell elongate and sometimes bifid, or absent; glandular hairs rare.

Leaves Usually alternate (spiral; sometimes opposite or verticillate), simple or pinnately compound (sometimes twice or several times), usually entire or pinnately lobed (rarely palmate or palmately compound), usually xeromorphic (thick, coriaceous, ericoid or hairy), with usually conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules absent; leaf sheath usually absent. Petiole base often swollen. Petiole vascular bundle transection? Venation usually pinnate, brochidodromous (rarely parallelodromous or palmate), or leaves one-veined. Stomata usually (brachy)paracytic (rarely anomocytic?; in Bellendena laterocytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids as clustered tubuli (Berberis type), chemically dominated by nonacosan-10-ol, or irregular platelets or as parallel grouped (usually non-entire) platelets (Hypericum type). Secretory cavities usually absent. Mesophyll usually with sclerenchymatous idioblasts (with asterosclereids, columellar or palisade sclereids). Idioblasts with ethereal oils absent. Leaf margin serrate (sometimes spinose-dentate), crenate or entire. Extrafloral nectaries sometimes present.

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, with flowers solitary or pairwise (representing reduced inflorescence branches; rarely with terminal flower as well) in spike-, spadix-, cone- or head-like, or compound inflorescence. Numerous species have pseudanthium with involucre consisting of often sepaloid to petaloid bracts.

Flowers Usually zygomorphic (often somewhat obliquely; rarely actinomorphic or asymmetric). Hypanthium present (calyx tube with stamens inserted at adaxial side) or absent. Hypogyny or perigyny. Sepals four, with valvate aestivation, petaloid, free or often connate in lower part into a tube (all four sepals or 3+1). Small, almost spiny, abaxial projection,‘Vorläuferspitze’, sometimes present immediately below tepal apex. Petals probably absent; in their place (two to) four hypogynous alternisepalous scales or glands, free or connate into annular often quadrilobate extrastaminal nectariferous disc (some species without nectaries). Receptacular nectaries present.

Androecium Stamens four, haplostemonous, antesepalous. Filaments usually free, mostly entirely or partially adnate to tepals (in Bellendena free from sepals). Anthers usually free (sometimes connivent, rarely connate?), basifixed, non-versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (lateral anthers often disporangiate; in Conospermum and Synaphea all disporangiate), usually introrse (rarely latrorse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective sometimes prolonged. Tapetum secretory. Staminodia usually absent (one or several staminodia present in some species).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually triporate (sometimes di- to octoporate, or di- to octocolporate; rarely di- to octocolpate; in Beauprea tricolpoidate), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Pores widely operculate, arranged according to Garside’s rule (known also in Santalales): apertures produced in threes at four points in tetraedral tetrad (in majority of Triaperturate Fischer’s rule: apertures produced pairwise on six points in tetrad); diporate pollen grains (in Embothrium and Banksieae) due to change from simultaneous to successive microsporogenesis and from tetraedral to decussate or tetragonal arrangement of microspores. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, reticulate or scabrate, echinate. Endexine usually absent (often present in Grevilleoideae).

Gynoecium Pistil composed of a single, entirely or partially closed carpel, usually stipitate (gynophore); carpel plicate, postgenitally entirely fused, without canal. Ovary superior or semi-inferior, monocarpellate and unilocular. Stylodium usually single (rarely absent), usually with apex expanded around stigma and specialized for secondary pollen presentation. Stigma single, terminal, subterminal or lateral (often slit-like), usually papillate, Dry or Wet type. Pistillodium absent?

Ovules Placentation marginal eller subapical (to subbasal?). Ovules usually one to three (rarely up to 100 or more) per carpel, hemianatropous, anatropous, amphitropous or orthotropous (micropyle directed downwards), pendulous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal. Outer integument two to nine cell layers thick. Inner integument two or three cell layers thick. Vascular bundles forming chalazal ring. Nucellar cap endothelial, approx. four cell layers thick. Megagametophyte Polygonum type. Position of megagametophyte very varying. Synergids usually with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells sometimes persistent. Endosperm formation ab initio nuclear, later usually entirely or partially cellular. Endosperm haustorium chalazal; megasporangial cells usually gradually degenerating, and endosperm without haustorium (megasporangial cells surrounding megagametophyte in Grevilleoideae rapidly degenerating, endosperm haustoria usually developed; in Lomatia, unicellular finger-like processes formed all over endosperm surface). Embryogenesis asterad.

Fruit A follicle, capsule, achene or drupe, often fused into a cone-like syncarp (often lignified and long persistent; often dehiscing only after fire). Pericarp and integument sometimes fused forming a caryopsoid fruit.

Seeds Aril absent. Elaiosome present in some species. Seed winged or unwinged. Seed coat usually testal. Testa sometimes multiplicative, occasionally reduced. Exotesta sometimes palisade. Endotesta often palisade, with fibrillar cells and calcium oxalate crystals. Exotegmen often fibrous. Endotegmen? Suspensor absent. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm usually absent (present, although weakly developed, in at least Bellendena and Persoonia). Embryo large, straight, oily and proteinaceous (starch absent), well differentiated, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons usually two (in Persoonia and Toronia three or more, in some species of Persoonia three to nine), large. Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar?

Cytology n = 5, 7, 10–14, 26, 28 – Chromosomes sometimes very large (particularly in Persoonioideae).

DNA Nuclear gene paleoAP3 present.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), flavonol derivatives, cyanidin, condensed tannins, ellagitannins, proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins), tropane alkaloids (bellendine present in Bellendena; methylbellendine and 2α-benzoyltropane present at least in Darlingia; benzoyltropine, benzoyltropane and phenylhydroxymethyl tropane present at least in Knightia and Darlingia), saponins, sapogenins, naphthoquinones, benzoquinones (rapanone, arbutin), tyrosine derived cyanogenic glycosides (dhurrin, proteacin, taxiphyllin, triglochinin), and quebrachitol present. Benzylisoquinoline alkaloids not found. Aluminium accumulated in many species of Grevilleoideae and Placospermum.

Use Ornamental plants, seeds (Macadamia integrifolia, M. tetraphylla), medicinal plants, dyeing substances, timber.

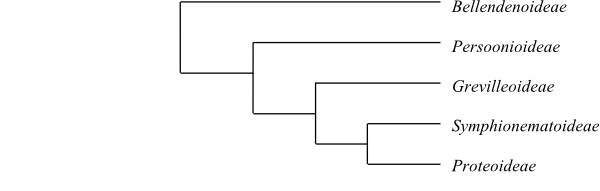

Systematics Proteaceae are sister-group to Platanus (Platanaceae). DNA sequence analyses of Proteaceae (Hoot & Douglas 1998) give the topology [Bellendenoideae+[Persoonioideae+[Symphionematoideae+[Proteoideae+Grevilleoideae]]]]. On the other hand, Weston & Barker (2006) identified the sister-group relationship [Bellendena+Persoonioideae].

Bellendenoideae P. H. Weston, Fl. Austral. 16: 472. 30 Nov 1995

1/1. Bellendena (1; B. montana; Tasmania). – Proteoid (cluster) roots present. Stomata laterocytic. Inflorescence a terminal raceme. Bracts absent. Filaments not adnate to tepals. Hypogynous glands absent. Ovules two per carpel. Fruit dry, winged, indehiscent. Endosperm usually present (weakly developed). Cotyledons not auriculate. n = 5. Chromosomes 6,5–7 μm long. Bellendine present. Aluminium accumulated.

[Persoonioideae+[Grevilleoideae+[Symphionematoideae+Proteoideae]]]

Stomata brachyparacytic. Tepals connate. Filaments adnate to tepals. Connective sometimes with appendage. Four nectary lobes usually present. Stylodia long. Endosperm present.

Persoonioideae Engl. in Engler et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. III, 1: 128. Mai 1888

2/110. Placospermeae C. T. White et W. D. Francis in Proc. roy. Soc. Queensland 35: 79. 1924. Placospermum (1; P. coriaceum; northeastern Queensland). – Persoonieae Endl., Gen. Plant.: 339. Dec 1837. ’Persoonia’ (c 100; paraphyletic?; Australia, New Caledonia (Garnieria) and New Zealand; incl. Toronia, Garnieria and Acidonia). – Australia, New Caledonia, New Zealand. Proteoid (cluster) roots absent (secondarily lost). Vestured pits present. Filaments entirely or largely adnate to tepals. Anthers free or basally (or entirely) adnate to tepals. Hypogynous glands present. Secondary pollen display absent. Ovules usually one or two (sometimes more than two) per carpel. Fruit usually a drupe (in Placospermum a follicle). Cotyledons obreniform. n = 7 (rarely n = 14). Mean length of chromosomes 9,1–14,4 μm. Aluminium accumulated in Placospermum.

[Grevilleoideae+[Symphionematoideae+Proteoideae]]

Flowers vertically or obliquely zygomorphic: tepals on one side split to base into four, or three tepals connate and one tepal free. Secondary pollen display present in some species (stylar apex collecting pollen grains). Ovules sometimes anatropous. x = 14. Mean length of chromosomes 0,5–5 μm.

Grevilleoideae Engl. in Engler et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. III, 1: 128. Mai 1888

45/855. Roupaleae Meisn., Plant. Vasc. Gen.: Tab. Diagn. 332, Comm. 245. 18-24 Jul 1841 [’Rhopaleae’]. Megahertzia (1; M. amplexicaulis; northeastern Queensland), Knightia (1; K. excelsa; New Zealand), Eucarpha (2; E. deplanchei, E. strobilina; New Caledonia), Triunia (4; T. erythrocarpa, T. montana, T. robusta, T. youngiana; eastern Queensland, northeastern New South Wales), Roupala (33; Mexico, Central America, Andean South America south to Argentina), Neorites (1; N. kevedianus; Queensland, southeastern New South Wales), Orites (9; eastern Queensland, eastern New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, Bolivia, Andean Chile), Lambertia (10; southwestern Western Australia, New South Wales), Xylomelum (7; X. angustifolium, X. benthamii, X. cunninghamianum, X. occidentale, X. pyriforme, X. salicinum, X. scottianum; western and eastern Australia), Helicia (c 100; South, East and Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea, Australia), Hollandaea (4; H. diabolica, H. porphyrocarpa, H. riparia, H. sayeriana; northeastern Queensland), Darlingia (2; D. darlingiana, D. ferruginea; northern Queensland), Floydia (1; F. praealta; southeastern Queensland, northeastern New South Wales). – Banksieae Dumort., Anal. Fam. Plant.: 18. 1829. Musgravea (2; M. heterophylla, M. stenostachya; northeastern Queensland), Austromuellera (2; A. trinervia, A. valida; northeastern Queensland), Banksia (c 170; northern, southwestern and eastern Australia, Tasmania). – Embothrieae Meisn. in A. P. de Candolle et A. L. P. P. de Candolle, Prodr. 14: 211, 443. Oct (med.) 1856.Lomatia (12; eastern Australia, Tasmania, Peru, Chile, western Argentina), Embothrium (2–8; E. coccineum, E. lanceolatum; southern Peru, Chile, western Argentina), Oreocallis (1; O. grandiflora; the Andes in Ecuador and Peru), Alloxylon (4; A. brachycarpum, A. flammeum, A. pinnatum, A. wickhamii; New Guinea, Aru Islands, eastern Queensland, eastern New South Wales), Telopea (5; T. aspera, T. mongaensis, T. oreades, T. speciosissima, T. truncata; New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania), Stenocarpus (21; New Guinea, Aru, northern and eastern Australia, New Caledonia), Strangea (3; S. cynanchicarpa, S. linearis, S. stenocarpoides; southwestern Western Australia, southeastern Queensland, northeastern New South Wales), Opisthiolepis (1; O. heterophylla; northeastern Queensland), Buckinghamia (2; B. celsissima, B. ferruginiflora; northeastern Queensland), Grevillea (c 360; Malesia to New Guinea, Australia, New Caledonia; paraphyletic?; incl. Hakea and Finschia?), Hakea (c 150; Australia; in Grevillea?), Finschia (3; F. chloroxantha, F. ferruginiflora, F. rufa; New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, Solomon Islands, Aru, Palau, Vanuatu; in Grevillea?). – Macadamieae Venkata Rao in Proc. Indian Acad. Sci. 48B: 23. 1968. Macadamia (9; Madagascar, Sulawesi, Queensland, New South Wales, New Caledonia; paraphyletic?; incl. Panopsis and Brabeium?), Panopsis (c 25; Central America, tropical South America; in Macadamia?), Brabeium (1; B. stellatifolium; Western Cape; in Macadamia?), Malagasia (1; M. alticola; Madagascar), Catalepidia (1; C. heyana; northeastern Queensland), Virotia (6; V. angustifolia, V. francii, V. leptophylla, V. neurophylla, V. rousselii, V. vieillardi; New Caledonia), Athertonia (1; A. diversifolia; northeastern Queensland), Heliciopsis (14; southeastern China, Burma, Thailand, Indochina, Malesia to the Philippines), Cardwellia (1; C. sublimis; northeastern Queensland), Sleumerodendron (1; S. austrocaledonicum; New Caledonia), Euplassa (c 20; South America, especially northwestern Andes, the Guayana Highlands and southeastern Brazil), Gevuina (1; G. avellana; southern Chile, southwestern Argentina), Bleasdalea (5; B. bleasdalei, B. ferruginea, B. lutea, B. papuana, B. vitiensis; New Guinea, northeastern Queensland), Hicksbeachia (2; H. pilosa, H. pinnatifolia; southeastern Queensland, northeastern New South Wales), Kermadecia (4; K. elliptica, K. pronyensis, K. rotundifolia, K. sinuata; New Caledonia). – Unplaced Grevilleoideae Sphalmium (1; S. racemosum; northeastern Queensland), Carnarvonia (1; C. araliifolia; northeastern Queensland). – South Africa, Madagascar, southern India, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia to New Guinea, Australia, Tasmania, Melanesia, Mexico to South America. Proteoid (cluster) roots present. Sieve elements with rosette-shaped non-dispersive protein bodies. Inflorescence usually a raceme of paired flowers (often subtende by a common bract) or a panicle of such racemes. Filaments basally to entirely adnate to tepals. Pollen grains with endexine often present also in apertural regions. Ovules (one or) two or several per carpel. Fruit a non-winged follicle with winged seeds, or a drupe. Seeds sometimes pachychalazal. Endosperm with chalazal nuclear haustorium. Cotyledons usually auriculate at base (rarely peltate). n = (10–)14(–15). Chromosomes 1,0–2,6 μm long. Aluminium accumulated in many species (not in Embothrieae). – Carnarvonia (Carnarvonioideae L. A. S. Johnson et B. G. Briggs in Bot. J. Lionn. Soc. 70: 172. 3 Sep 1975) and Sphalmium (Sphalmioideae L. A. S. Johnson et B. G. Briggs in Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 70: 172. 3 Sep 1975) are provisionally included in Grevilleoideae, yet morphologically very distinct and possibly sister-groups.

[Symphionematoideae+Proteoideae]

Fruit indehiscent, dry.

Symphionematoideae P. H. Weston et N. P. Barker in Telopea 11: 330. 13 Nov 2006

2/3. Agastachys (1; A. odorata; western Tasmania), Symphionema (2; S. montanum, S. paludosum; eastern New South Wales). – Southeastern Australia, Tasmania. Proteoid (cluster) roots absent. Spicate inflorescence (in Symphionema often compound). Hypogynous glands (nectaries) absent. Filaments adnate at base to tepals. Ovules one or two per carpel. Cotyledons not auriculate. n = 10, 14. Chromosomes c. 3 μm long.

Proteoideae Eaton, Bot. Dict., ed. 4: 30. Apr-Mai 1836 [‘Proteae’]

25/640. Conospermeae Endl., Gen. Plant.: 338. Dec 1837. Stirlingia (7; S. abrotanoides, S. anethifolia, S. divaricatissima, S. latifolia, S. seselifolia, S. simplex, S. tenuifolia; southwestern Western Australia), Conospermum (53; Australia), Synaphea (c 50; southwestern Western Australia). – Petrophileae P. H. Weston et N. P. Barker in Telopea 11: 331. 13 Nov 2006.Petrophile (53; southwestern, southern and eastern Australia), Aulax (3; A. cancellata, A. pallasia, A. umbellata; Western Cape). – Proteeae Dumort., Anal. Fam. Plant.: 18. 1829 [‘Proteae’]. Protea (103 or 114; eastern and southern Africa), Faurea (c 15; Africa, Madagascar). – Leucadendreae P. H. Weston et N. P. Barker in Telopea 11: 332. 13 Nov 2006. Isopogon (c 35; Australia), Adenanthos (33; southwestern Western Australia, South Australia, western Victoria), Leucadendron (80–85; Western and Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal), Serruria (c 50; Western Cape), Paranomus (18–19; Western Cape, southern Eastern Cape), Vexatorella (4; V. alpina, V. amoena, V. latebrosa, V. obtusata; southern Northern Cape, central Western Cape), Sorocephalus (11; Western Cape), Spatalla (20; Western Cape), Leucospermum (c 50; Western and Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal, Zimbabwe), Mimetes (13; Western Cape), Diastella (7; D. buekii, D. divaricata, D. fraterna, D. myrtifolia, D. parilis, D. proteoides, D. thymelaeoides; Western Cape), Orothamnus (1; O. zeyheri; the Kogelberg area in Western Cape); incertae sedis: Eidothea (2; E. hardeniana, E. zoexylocarya; northeastern Queensland, northeastern New South Wales), Beauprea (13; New Caledonia), Beaupreopsis (1; B. paniculata; New Caledonia), Dilobeia (2; D. tenuinervis, D. thouarsii; Madagascar), Cenarrhenes (1; C. nitida; Tasmania), Franklandia (2; F. fucifolia, F. triaristata; southwestern Western Australia). – Africa south of Sahara (with their highest diversity in the Cape region), Madagascar, Australia. Sometimes herbaceous. Proteoid (cluster) roots present. Sieve elements with non-dispersive protein bodies. Inflorescence basically racemose, often compound, often condensed into spikes or capitula. Flowers sessile. Hypanthium sometimes present. Filaments poorly to entirely adnate to tepals. Anthers sometimes monothecal. Ovule usually one (in some species of Petrophile and Isopogon sometimes two) per carpel. Fruit often a one-seeded drupe or nut. Cotyledons not auriculate. n = (10–)11–13(–14). Chromosomes 1,2–3,4 μm long. Aluminium rarely accumulated.

|

Cladogram (simplified) of Proteaceae based on DNA sequence data (Hoot & Douglas 1998). Bellendena is sister to Persoonioideae in analyses by, e.g., Weston & Barker (2006). |

Literature

Ahuja R. 1966. Morphological and embryological studies on Nelumbo nucifera (Gaertn.) Willd. – Delhi.

Askin RA, Baldoni AM. 1998. The Santonian through Paleogene record of Proteaceae in the southern South America-Antarctic Peninsula region. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 11: 373-390.

Auld TD, Denham AJ. 1999. The role of ants and mammals in dispersal and post-dispersal seed predation of the shrubs Grevillea (Proteaceae). – Plant Ecol. 144: 201-213.

Baas P. 1969. Comparative anatomy of Platanus kerrii Gagnep. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 62: 413-421.

Balthazar M von, Schönenberger J. 2009. Floral structure and organization in Platanaceae. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 170: 210-225.

Banks H, Stafford P, Crane P. 2007. Aperture variation in the pollen of Nelumbo (Nelumbonaceae). – Grana 46: 157-162.

Barker NP, Weston PH, Rourke JP, Reeves G. 2002. The relationships of the southern African Proteaceae as elucidated by internal transcribed spacer (ITS) DNA sequence data. – Kew Bull. 57: 867-883.

Barker NP, Vanderpoorten A, Morton CM, Rourke JP. 2004. Phylogeny, biogeography, and the evolution of life-history traits in Leucadendron (Proteaceae). – Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 33: 845-860.

Barker NP, Weston PH, Rutschmann F, Sauquet H. 2007. Molecular dating of the ‘Gondwanan’ plant family Proteaceae is only partially congruent with the timing of the break-up of Gondwana. – J. Biogeogr. 34: 2012-2027.

Barraclough TG, Reeves G. 2005. The causes of speciation in plant lineages: Species-level DNA trees in the African genus Protea. – In: Bakker FT, Chatrou LW, Gravendeel B, Pelser PB (eds), Plant species-level systematics: new perspectives on pattern and process, A. R. G. Gantner, Ruggel, Liechtenstein, pp. 31-46. [Regnum Vegetabile 143]

Barthlott W, Neihhuis C, Jetter R, Bouraul T, Riederer M. 1966. Waterlily, poppy, or sycamore: on the systematic position of Nelumbo. – Flora 191: 169-174.

Batygina TB, Shamrov II. 1983. Embryology of the Nelumbonaceae and Nymphaeaceae: pollen grain structure. – Bot. Žurn. 68: 1177-1183. [In Russian]

Batygina TB, Shamrov II. 1985. Comparative embryology of Nymphaeales and Nelumbonales orders and the problems of their taxonomy and phylogeny. – Bot. Žurn. 70: 368-373. [In Russian]

Batygina TB, Kravtsova TI, Shamrov II. 1980. Comparative embryology of some representatives of the orders Nymphaeales and Nelumbonales. – Bot. Žurn. 65: 1071-1087. [In Russian]

Batygina TB, Shamrov II, Kolesova GE. 1982. Embryology of Nymphaeales and Nelumbonales II. Development of the female embryonic structures. – Bot. Žurn. 67: 1179-1195. [In Russian]

Beard JS. 1992. The proteas of tropical Africa. – Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst.

Bernhardt P, Weston PH. 1996. The pollination ecology of Persoonia (Proteaceae) in eastern Australia. – Telopea 6: 775-804.

Bieleski RL, Briggs BG. 2005. Taxonomic patterns in the distribution of polyols within the Proteaceae. – Aust. J. Bot. 53: 205-217.

Blackmore S, Barnes SH. 1995. Garside’s rule and the microspore tetrads of Grevillea rosmarinifolia A. Cunningham and Dryandra polycephala Bentham (Proteaceae). – Rev. Palaeobot. Palyn. 85: 111-121.

Bond WJ. 1985. Canopy-stored seed reserves (serotiny) in Cape Proteaceae. – South Afr. J. Bot. 51: 181-186.

Bond WJ. 1988. Proteas as ‘tumbleseeds’: wind dispersal through the air and over soil. – South Afr. J. Bot. 54: 455-460.

Bond WJ, Breytenbac GJ. 1985. Ants, rodents and seed predation in Proteaceae. – South Afr. J. Zool. 20: 150-154.

Bonifaz C, Cornejo X. 2002. 29. Proteaceae. – In: Harling G, Andersson L (eds), Flora of Ecuador 69, Botanical Institute, Göteborg University, pp. 5-48.

Boothroyd LE. 1930. The morphology and anatomy of the inflorescence and flower of the Platanaceae. – Amer. J. Bot. 17: 678-693.

Borsch TS, Barthlott W. 1994. Classification and distribution of the genus Nelumbo Adans. (Nelumbonaceae). – Beitr. Biol. Pflanzen 68: 421-450.

Borsch TS, Wilde V. 2000. Pollen variability within species, populations, and individuals, with particular reference to Nelumbo. – In: Harley MM, Morton CM, Blackmore S (eds), Pollen and spores: morphology and biology, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, pp. 285-299.

Bosser J, Rabevohitra R. 1991. Protéacées. – In: Morat P (ed), Flore de Madagascar et des Comores, Fam. 45, 57, 93, 94, 107, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, pp. 47-69.

Brett DW. 1979. Ontogeny and classification of the stomatal complex of Platanus L. – Ann. Bot. 44: 249-251.

Bretzler E. 1929. Über den Bau der Platanenblüte und die systematische Stellung der Platanen. – Engl. Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 62: 305-309.

Bretzler E. 1938. Bau der Platanenblüte und systematische Stellung der Platanen. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 62: 305-309.

Briggs BG, Hyland BPM, Johnson LAS. 1975. Sphalmium, a distinctive new genus of Proteaceae from North Queensland. – Aust. J. Bot. 23: 165-172.

Brouwer J. 1924. Studies in Platanaceae. – Extr. Rec. Trav. Bot. Néerl. 21: 369-382.

Brush WD. 1917. Distinguishing characters of North American sycamore woods. – Bot. Gaz. (Crawfordsville) 64: 480-496.

Carolin R. 1961. Pollination of the Proteaceae. – Aust. Mus. Mag. 1961(sep): 371-374.

Carpenter RJ. 1994. Cuticular morphology and aspects of the ecology and fossil history of North Queensland rainforest Proteaceae. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 116: 249-303.

Carpenter RJ, Jordan GJ. 1997. Early Tertiary macrofossils of Proteaceae from Tasmania. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 10: 533-563.

Carpenter RJ, Jordan GJ, Hill RS. 1994. Banksieaephyllum taylorii (Proteaceae) from the Late Paleocene of New South Wales and its relevance to the origin of Australia’s scleromorphic flora. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 7: 385-392.

Carpenter RJ, Hill RS, Jordan GJ. 2005. Leaf cuticular morphology links Platanaceae and Proteaceae. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 166: 843-855.

Carpenter RJ, Bannister JM, Jordan GJ, Lee DE. 2010. Leaf fossils of Proteaceae tribe Persoonieae from the Late Oligocene-Early Miocene of New Zealand. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 23: 1-15.

Carpenter RJ, Jordan GJ, Lee DE, Hill RS. 2010. Leaf fossils of Banksia (Proteaceae) from New Zealand: an Australian abroad. – Amer. J. Bot. 97: 288-297.

Carpenter RJ, Bannister JM, Lee DE, Jordan GJ. 2013. Proteaceae leaf fossils from the Oligo-Miocene of New Zealand: new species and evidence of biome and trait conservatism. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 25: 375-389.

Carpenter RJ, McLoughlin S, Hill RS, McNamara

KJ, Jordan GJ. 2014. Early evidence of xeromorphy in angiosperms: stomatal

encryption in a new Eocene species of Banksia (Proteaceae) from Western Australia. –

Amer. J. Bot. 101: 1486-1497.

Carpenter RJ, Jordan GJ, Hill RS. 2016. Fossil leaves of Banksia, Banksieae and pretenders: resolving the fossil genus Banksieaephyllum. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 29: 126-141.

Carpenter RJ, Tarran M, Hill RS. 2017. Leaf fossils of Proteaceae subfamily Persoonioideae, tribe Persoonieae: tracing the past of an important Australasian sclerophyll lineage. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 30: 148-158.

Catling DM. 2010. Vegetative anatomy in Finschia Warb. and its place in Hakeinae (Proteaceae). – Telopea 12: 491-504.

Catling DM, Gates PJ. 1995. Leaf anatomy in Hakea Schrader (Proteaceae). – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 117: 153-172.

Catling DM, Gates PJ. 1998. Nodal and leaf anatomy in Grevillea R. Br. (Proteaceae). – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 120: 187-227.

Chattaway MM. 1948. The wood anatomy of the Proteaceae. – Aust. J. Sci. Res., Sect. B, 1: 279-302.

Chisumpa SM, Brummitt RK. 1987. Taxonomic notes on tropical African species of Protea. – Kew Bull. 42: 815-853.

Christophel DC. 1984. Early Tertiary Proteaceae: the first floral evidence for the Musgraveinae. – Aust. J. Bot. 32: 177-186.

Citerne HL, Reyes E, Le Guilloux M, Delannoy E, Simonnet F, Sauquet H, Weston PH, Nadot S, Damerval C. 2017. Characterization of CYCLOIDEA-like genes in Proteaceae, a basal eudicot family with multiple shifts in floral symmetry. – Ann. Bot. 119: 367-378.

Collins BG, Rebelo T. 1987. Pollination biology of the Proteaceae in Australia and southern Africa. – Aust. J. Ecol. 12: 387-422.

Cowling RM, Lamont BB. 1998. On the nature of Gondwanan species flocks: diversity of Proteaceae in Mediterranean south-western Australia and South Africa. – Aust. J. Bot. 46: 335-355.

Crane PR, Manchester SR, Dilcher DL. 1988. Morphology and phylogenetic significance of the angiosperm Platanites hebridicus from the Palaeocene of Scotland. – Palaeontology 31: 503-517.

Crane PR, Pedersen KR, Friis EM, Drinnan AN. 1993. Early Cretaceous (Early to Middle Albian) platanoid inflorescences associated with Sapindopsis leaves from the Potomac group of eastern North America. – Syst. Bot. 18: 328-344.

Cunningham L. 1998. An examination of the Nelly Creek flora and cuticular identification of fossil and extant Proteaceae. – Unpubl. Honours Diss., University of Adelaide, South Australia.

Dacey JWH. 1987. Knudsen-transitional flow and gas pressurization in leaves of Nelumbo. – Plant Physiol. 85: 199-203.

De Castro O, Di Maio A, Lozada García JA, Piacenti D, Vázquez-Torres M, De Luca P. 2013. Plastid DNA sequencing and nuclear SNP genotyping help resolve the puzzle of central American Platanus. – Ann. Bot. 112: 589-602.

Denk T, Tekleva MV. 2006. Comparative pollen morphology and ultrastructure of Platanus: implications for phylogeny and evaluation of the fossil record. – Grana 45: 195-221.

Dettmann ME. 1998. Pollen morphology of Eidotheoideae: implications for phylogeny in the Proteaceae. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 11: 605-612.

Dettmann ME, Clifforn HT. 2005. Fossil fruit of the Grevilleeae (Proteaceae) in the Tertiary of eastern Australia. – Mem. Queensland Mus. 51: 359-374.

Dettmann ME, Jarzen DM. 1991. Pollen evidence for the Late Cretaceous differentiation of Proteaceae in southern polar forests. – Can. J. Bot. 69: 901-906.

Dettmann ME, Jarzen DM. 1996. Pollen of proteaceous-type from latest Cretaceous sediments, southeastern Australia. – Alcheringa 20: 103-106.

Dettmann ME, Jarzen DM. 1998. The early history of the Proteaceae in Australia: the pollen record. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 11: 401-438.

Dillon RJ. 2002. The diversity of scleromorphic structures in leaves of Proteaceae. – Honours Thesis, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia.

Dinkelaker B, Hengeler C, Marschner H. 1995. Distribution and function of proteoid roots and other root clusters. – Bot. Acta 108: 183-200.

Douglas AW. 1994. Evolutionary patterns in Proteaceae based on comparative floral and inflorescence ontogenies. – Ph.D. diss., Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Douglas AW. 1996. Inflorescence and floral development of Carnarvonia (Proteaceae). – Telopea 6: 749-774.

Douglas AW, Tucker SC. 1996a. Inflorescence ontogeny and floral organogenesis in Grevilleoideae (Proteaceae) with emphasis on the nature of flower parts. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 157: 341-372.

Douglas AW, Tucker SC. 1996b. The developmental basis of diverse carpel orientations in Grevilleoideae (Proteaceae). – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 157: 373-397.

Douglas AW, Tucker SC. 1996c. Comparative floral ontogenies among Persoonioideae including Bellendena (Proteaceae). – Amer. J. Bot. 83: 1528-1555.

Douglas AW, Tucker SC. 1997. The developmental basis of morphological diversification and synorganization in flowers of Conospermeae (Stirlingia and Conosperminae: Proteaceae). – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 158(Suppl.): S13-S48.

Douglas AW, Hill RS, Scriben LJ, Jordan GJ, Maynard GV, Orchard AE, Weston PH. 1995. Proteaceae I. – In: Orchard AE (ed), Flora of Australia 16, CSIRO, Melbourne, Australia, pp. 4-500.

Downing TL, Duretto MF, Ladiges PY. 2004. Morphological analysis of the Grevillea ilicifolia complex (Proteaceae) and recognition of taxa. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 17: 327-341.

Edwards KS, Prance GT. 1993. New species of Panopsis (Proteaceae) from South America. – Kew Bull. 48: 637-662.

Edwards KS, Prance GT. 2003. Four new species of Roupala (Proteaceae). – Brittonia 55: 61-68.

Elsworth JF, Martin KR. 1971. Flavonoids of the Proteaceae 1. A chemical contribution to studies on the evolutionary relationships in the South African Proteoideae. – J. South Afr. Bot. 37: 199-212.

Engler A. 1889. Proteaceae. – In: Engler A, Prantl K (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien III(1), W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 119-156; Engler A. 1897. Nachträge zu III(1), pp. 123-124.

Esau K. 1975. The phloem of Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. – Ann. Bot. 39: 901-913.

Esau K, Kosakai H. 1975a. Laticifers in Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn.: distribution and structure. – Ann. Bot. 39: 713-719.

Esau K, Kosakai H. 1975b. The phloem of Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. – Ann. Bot. 39: 901-913.

Esau K, Kosakai H. 1975c. Leaf arrangement in Nelumbo nucifera: a re-examination of a unique phyllotaxy. – Phytomorphology 25: 100-112.

Estrada-Ruiz E, Upchurch GR Jr, Wolfe JA, Cevallos-Ferriz SRS. 2011. Comparative morphology of fossil and extant leaves of Nelumbonaceae, including a new genus from the Late Cretaceous of Western North America. – Syst. Bot. 36: 337-351.

Faegri K. 1965. Reflections on the development of pollination systems in African Proteaceae. – J. South Afr. Bot. 31: 133-136.

Farr C. H. 1922. The meiotic cytokinesis in Nelumbo. – Amer. J. Bot. 9: 296-306.

Feng Y, Oh S-H, Manos PS. 2005. Phylogeny and historical biogeography of the genus Platanus as inferred from nuclear and chloroplast DNA. – Syst. Bot. 30: 786-799.

Feuer S. 1986. Pollen morphology and evolution in the Persoonioideae, Sphalmioideae, and Carnarvonioideae (Proteaceae). – Pollen Spores 28: 123-156.

Feuer S. 1989. Pollen morphology of the Embothrieae (Proteaceae) I. Buckinghamiinae, Stenocarpinae and Lomatiinae. – Grana 28: 225-242.

Feuer S. 1990a. Pollen aperture evolution among the subfamilies Persoonioideae, Sphalmioideae, and Carnarvonioideae (Proteaceae). – Amer. J. Bot. 77: 783-794.

Feuer S. 1990b. Pollen morphology of the Embothrieae (Proteaceae) II. Embothriinae (Embothrium, Oreocallis, Telopea). – Grana 29: 19-36.

Filla F. 1926. Das Perikarp der Proteaceae. – Flora 120: 99-142.

Floyd SK, Lerner VT, Friedman WE. 1999. A developmental and evolutionary analysis of embryology in Platanus (Platanaceae), a basal eudicot. – Amer. J. Bot. 86: 1523-1537.

Foreman DB. 1983. A review of the genus Helicia Lour. (Proteaceae) in Australia. – Brunonia 6: 59-72.

Foreman DB. 1998. New species of Helicia Lour. (Proteaceae) from the Vogelkop Peninsula, Irian Jaya. – Kew Bull. 53: 669-681.

Friis EM, Crane PR, Pedersen KR. 1988. Reproductive structures of Cretaceous Platanaceae. – Kong. Danske Vidensk. Selsk., Biol. Skr. 31: 1-56.

Fuss AM, Sedgley M. 1991. Pollen tube growth and seed set of Banksia coccinea R. Br. (Proteaceae). – Ann. Bot. 68: 377-384.

Gandolfo MA, Cuneo RN. 2005. Fossil Nelumbonaceae from the La Colonia Formation (Campanian-Maastrichtian, Upper Cretaceous), Chubut, Patagonia, Argentina. – Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 133: 169-178.

Garside S. 1946. The developmental morphology of the pollen of Proteaceae. – J. South Afr. Bot. 12: 27-34.

George AS. 1981. The genus Banksia. – Nuytsia 3: 239-474.

George AS. 1998. Proteas in Australia. An overview of the current state of taxonomy of the Australian Proteaceae. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 11: 257-266.

George AS. 2014. The case against the

transfer of Dryandra to Banksia (Proteaceae). – Ann. Missouri Bot.

Gard. 100: 32-49.

Goldingay RL, Carthew SM. 1998. Breeding and mating systems of Australian Proteaceae. – Aust. J. Bot. 46: 421-437.

Golovneva LB. 2007. Occurrence of Sapindopsis (Platanaceae) in the Cretaceous of Eurasia. – Paleontol. J. 41: 1077-1090.

Golovneva LB. 2008. A new platanaceous genus Tasymia (angiosperms) from the Turonian of Siberia. – Paleontol. J. 42: 192-202.

Gonzalez CC, Gandolfo MA, Zamaloa MC, Cúneo NR, Wilf P, Johnson KR. 2007. Revision of the Proteaceae macrofossil record from Patagonia, Argentina. – Bot. Rev. 73: 235-266.

Greenwood DR, Haines PW, Steart DC. 2001. New species of Banksieaeformis and a Banksia ‘cone’ (Proteaceae) from the Tertiary of central Australia. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 14: 871-890.

Grimm GW, Denk T. 2008. ITS evolution in Platanus (Platanaceae): homoeologues, pseudogenes and ancient hybridization. – Ann. Bot. 101: 403-419.

Grimm GW, Denk T. 2010. The reticulate origin of modern plane trees (Platanus, Platanaceae): a nuclear marker puzzle. – Taxon 59: 134-147.

Gross CL, Hyland BPM. 1993. Two new species of Macadamia (Proteaceae) from North Queensland. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 6: 343-350.

Guédès M. 1972. L’ochrea ligulaire de la feuille de Platane. – Phyton 14: 263-269.

Gupta SC, Ahluwalia R. 1977. The carpel of Nelumbo nucifera. – Phytomorphology 27: 274-282.

Gupta SC, Ahluwalia R. 1979. The anther and ovule of Nelumbo nucifera: a reinvestigation. – J. Indian Bot. Soc. 58: 177-182.

Gupta SC, Anuja R. 1967. Is Nelumbo a monocot? – Naturwissenschaften 54: 498.

Gupta S, Paliwal GS, Ahuga R. 1968. The stomata of Nelumbo nucifera: formation, distribution, and degeneration. – Amer. J. Bot. 55: 295-301.

Gusejnova NA. 1976. On cytoembryology in Platanaceae. – Bjull. Glavn. Bot. Sada 102: 67-71.

Haber JM. 1959. The comparative anatomy and morphology of the flowers and inflorescences of the Proteaceae I. Some Australian taxa. – Phytomorphology 9: 325-358.

Haber JM. 1961. The comparative anatomy and morphology of the flowers and inflorescences of the Proteaceae II. Some American taxa. – Phytomorphology 11: 1-16.

Haber JM. 1966. The comparative anatomy and morphology of the flowers and inflorescences of the Proteaceae III. Some African taxa. – Phytomorphology 16: 490-527.

Hall TF, Penfound WT. 1944. The biology of the American lotus, Nelumbo lutea (Wild.) Pers. – Amer. Midl. Natur. 31: 744-758.

Hammill KA, Bradstock RA, Allaway WG. 1998. Postfire seed dispersal and species re-establishment in proteaceous heath. – Aust. J. Bot. 46: 407-419.

Hayes V, Schneider EL, Carlquist S. 2000. Floral development of Nelumbo nucifera (Nelumbonaceae). – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 161(Suppl.): S183-S191.

He T, Lamont BB, Downes KS. 2011. Banksia born to burn. – New Phytol. 191: 184-196.

Heide-Jørgensen HS. 1978. The xeromorphic leaves of Hakea suaveolens R. Br. II. Structure of epidermal cells, cuticle development and ectodesmata. – Bot. Tidsskr. 72: 227-244.

Hernández G, Enrique L. 1991. Revisión de las especies Colombianas del género Panopsis (Proteaceae). – Caldasia 16: 459-484.

Herscovitch JC, Martin ARH. 1989. Pollen-pistil interactions in Grevillea banksii – the pollen grain, stigma, transmitting tissue and in vitro pollinations. – Grana 28: 69-84.

Herscovitch JC, Martin ARH. 1990. Pollen-pistil interactions in Grevillea banksii 2. Pollen tube ultrastructure and interactions, and results of field experiment. – Grana 29: 5-17.

Hill RS. 1998. Fossil evidence for the onset of xeromorphy and scleromorphy in Australian Proteaceae. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 11: 391-400.

Hill RS, Scriven LJ, Jordan GJ. 1995. The fossil record of Australian Proteaceae. – In: McCarthy PM (ed), Flora of Australia 16. Elaeagnaceae, Proteaceae 1, A.B.R.S./C.S.I.R.O., Collingwood, Melbourne, pp. 21-30.

Holmes GD, Downing TL, James EA, Blacket MJ,

Hoffmann AA, Bayly MJ. 2014. Phylogeny of the holly grevilleas (Proteaceae) based on nuclear ribosomal

and chloroplast DNA. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 27: 56-77.

Holmes GD, Weston PH, Murphy DJ, Connlly C, Cantrill DJ. 2018. The genealogy of geebungs: phylogenetic analysis of Persoonia (Proteaceae) and related genera in subfamily Persoonioideae. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 31: 166-189.

Hoot SB, Douglas AW. 1998. Phylogeny of the Proteaceae based on atpB and atpB-rbcL intergenic spacer region sequences. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 11: 301-320.

Ishida H, Umino T, Tsuji K, Kosuge T. 1988. Studies on the antihemorrhagic substances in herbs classified as hemostatics in Chinese medicine VIII. On the antihemorrhagic principle in nelumbins receptaculum. – Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 36: 4585-4587.

Ito M. 1986. Studies in the floral morphology and anatomy of Nymphaeales IV. Floral anatomy of Nelumbo nucifera. – Acta Phytotaxon. Geobot. 37: 82-96.

Ito M. 1987. Phylogenetic systematics of the Nymphaeales. – Bot. Mag. (Tokyo) 100: 17-36.

Jankó J. 1890. Abstammung der Platanen. – Engl. Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 1: 412-458.

Johnson LAS, Briggs BG. 1963. Evolution in the Proteaceae. – Aust. J. Bot. 11: 21-61.

Johnson LAS, Briggs BG. 1975. On the Proteaceae – the evolution and classification of a southern family. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 70: 83-182.

Johnson LAS, Briggs BG. 1981. Three old southern families: Myrtaceae, Proteaceae, and Restionaceae. – In: Keast A (ed), Ecological biogeography of Australia 1-3, The Hague, pp. 429-469.

Johnson LAS, McGillivray DJ. 1975. Conospermum Sm. (Proteaceae) in eastern Australia. – Telopea 1: 58-65.

Jones BMG. 1968. The origin of London Plane. – Proc. Bot. Soc. Brit. Isles 7: 507-508.

Jönsson B. 1878-1879. Bidrag till kännedomen om bladets anatomiska byggnad hos Proteaceerne. – Acta Univ. Lund. 15: 1-49.

Jordaan PG. 1944. Die morphologie van die saadknop van Suid-Afrikaanse Proteaceae. – D.Sc. diss., University of Stellenbosch, South Africa.

Jordan GJ, Hill RS. 1991. Two new Banksia species from Pleistocene sediments in western Tasmania. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 4: 499-511.

Jordan GJ, Carpenter RJ, Hill RS. 1998. The macrofossil record of Proteaceae in Tasmania: a review with new species. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 11: 465-501.

Jordan GJ, Dillon RA, Weston PH. 2005. Solar radiation as a factor in the evolution of scleromorphic leaf anatomy in Proteaceae. – Amer. J. Bot. 92: 789-796.

Jordan GJ, Weston PH, Carpenter RJ, Dillon RA, Brodribb TJ. 2008. The evolutionary relations of sunken, covered, and encrypted stomata to dry habitats in Proteaceae. – Amer. J. Bot. 95: 521-530.

Kak AM, Durani S. 1986. A contribution to the seed anatomy of Nelumbium nuciferum Gaertn. – J. Plant Anat. Morph. 3: 59-64.

Kalinganire A, Harwood CE, Slee MU, Simons AJ. 2000. Floral structure, stigma receptivity and pollen viability in relation to protandry and self-incompatibility in silky oak (Grevillea robusta A. Cunn.). – Ann. Bot. 86: 133-148.

Kane ME, Sheehan TJ, Ferwerda FH. 1988. In vitro growth of American lotus embryos. – Hortscience 23: 611-613.

Kan-Fan C, Lounasmaa M. 1973. Sur les alcaloïdes de Knightia deplanchei Vieill. ex Brongn. et Gris (Protéacées). – Acta Chem. Scand. 27: 1039-1052.

Kaouadji M. 1986a. New prenylated flavanones from Platanus acerifolia buds. – J. Nat. Prod. 49: 153-155.

Kaouadji M. 1986b. Grenoblone, nouvelle oxodihydrochalcone des bourgeons de Platanus acerifolia. – J. Nat. Prod. 49: 500-503.

Kaouadji M, Ravanel P. 1990. Further non-polar flavonols from Platanus acerifolia buds. – Phytochemistry 29: 1348-1350.

Kaouadji M, Ravanel P, Tissut M, Creizet S. 1988. Novel methylated flavonols with unsubstituted B-ring from Platanus acerifolia. – J. Nat. Prod. 51: 353-356.

Kausik SB. 1940. Vascular anatomy of the flower of Macadamia tenuifolia F. Muell. (Proteaceae). – Curr. Sci. 9: 22-25.

Kausik SB. 1941. Studies in the Proteaceae V. Vascular anatomy of the flower of Grevillea robusta Cunn. – Proc. Natl. Inst. Sci. India 7: 257-266.

Khanna P. 1965. Morphology and embryological studies in Nymphaeaceae II. Brasenia schreberi Gmel. and Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. – Aust. J. Bot. 13: 379-387.

Knobloch E. 1997. “Credneria” bohemica Velenovský – eine altertümliche Platane. – Palaeontographica, Ser. B, 1242: 127-148.

Kochummen KM. 1973. Notes on the systematics of Malayan phanerogams XXII. Heliciopsis (Proteaceae). – Gard. Bull. (Singapore) 26: 286-287.

Kosakai H, Moseley MF, Cheadle VI. 1970. Morphological studies of the Nymphaeaceae V. Does Nelumbo have vessels? – Amer. J. Bot. 57: 487-494.

Krassilov VA, Shilin PV. 1995. New platanoid staminate heads from the mid-Cretaceous of Kazakhstan. – Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 85: 207-211.

Krauss SL, Johnson LAS. 1991. A revision of the complex species Persoonia mollis (Proteaceae). – Telopea 4: 185-199.

Kreunen SK, Osborn JM. 1999. Pollen and anther development in Nelumbo (Nelumbonaceae). – Amer. J. Bot. 86: 1662-1676.

Kristen U. 1971. Licht- und Elektronenmikroskopische Untersuchungen zur Entwicklung der Hydropoten von Nelumbo nucifera. – Ber. Deutsch. Bot. Ges. 84: 211-214.

Kubitzki K. 1993. Platanaceae. – In: Kubitzki K, Rohwer JG, Bittrich V (eds), The families and genera of vascular plants II. Flowering plants. Dicotyledons. Magnoliid, hamamelid and caryophyllid families, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 521-522.

Kvacek Z, Manchester SR. 2004. Vegetative and reproductive structure of the extinct Platanus neptuni from the Tertiary of Europe and relationships within the Platanaceae. – Plant Syst. Evol. 244: 1-29.

Kvacek Z, Manchester SR, Guo Z-H. 2001. Trifoliolate leaves of Platanus bella (Heer) comb. n. from the Palaeocene of North America, Greenland, and Asia and their relationships among extinct and extant Platanaceae. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 162: 441-458.

Ladd PG, Alkema AJ, Thomson GJ. 1996. Pollen presenter morphology and anatomy in Banksia and Dryandra. – Aust. J. Bot. 41: 447-471.

Ladd PG, Nanni I, Thomson GJ. 1998. Unique stigmatic structure in three genera of Proteaceae. – Aust. J. Bot. 46: 479-488.

Lambers H, Finneban PM, Laliberté E, Pearse SJ, Ryan MH, Shane MW, Veneklaas EJ. 2011. Phosphorus nutrition of Proteaceae in severly-impoverished soils: are there lessons to be learned for future crops? – Plant Physiol. 156: 1058-1066.

Lamont BB, Groom PK. 1998. Seed and seedling biology of the woody-fruited Proteaceae. – Aust. J. Bot. 46: 387-406.

Langlet O, Söderberg E. 1929. Über die Chromosomenzahlen einiger Nymphaeaceen. – Acta Horti Berg. 9: 85-104.

Lanyon JW. 1979. The wood anatomy of three proteaceous timbers Placospermum coriaceum, Dilobuia thouarsii and Garnieria spathulaefolia. – IAWA Bull. 1979: 27-33.

Lee HM. 1978. Studies of the family Proteaceae II. Further observations on the root morphology of some Australian genera. – Proc. Roy. Soc. Victoria 90: 251-256.

Leenwen WAM van. 1963. A study of the structure of the gynoecium of Nelumbo lutea (Willd.) Pers. – Acta Bot. Neerl. 12: 84-97.

Leroy J-F. 1982. Origine et évolution du genre Platanus (Platanaceae). – Compt. Rend. Acad. Sci. Paris, sér. III, 295: 251-254.

Les DH, Garvin DK, Wimpee CF. 1991. Molecular evolutionary history of ancient aquatic angiosperms. – Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88: 10119-10123.

Levyns MR. 1958. The phytogeography of members of Proteaceae in Africa. – J. South Afr. Bot. 24: 1-9.

Levyns MR. 1970. A revision of the genus Paranomus (Proteaceae). – Contr. Bolus Herb. 2: 3-48.

Li H-L. 1955. Classification and phylogeny of Nymphaeaceae and allied families. – Amer. Midl. Nat. 54: 33-41.

Li J-K, Huang S-Q. 2009. Flower thermoregulation facilitates fertilization in Asian sacred lotus. – Ann. Bot. 103: 1159-1163.

Liu H, Yan G, Shan F, Sedgley R. 2006. Karyotypes in Leucadendron (Proteaceae): evidence of the primitiveness of the genus. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 151: 387-394.

Lounasmaa M. 1975. Sur les alcaloïdes mineurs de Knightia deplanchei. – Planta Medica 27: 83-88.

Lyon HL. 1901. Observations on the embryology of Nelumbo. – Minnesota Bot. Stud., Ser. II, 38(5).

McDonald JA, Ismail R. 1995. Macadamia erecta (Proteaceae), a new species from Sulawesi. – Harvard Pap. Bot. 7: 7-10.

McGillivray DJ. 1975. Australian Proteaceae: new taxa and notes. – Telopea 1: 19-32.

McLay TGB, Bayly MJ, Ladiges PY. 2016. Is south-western Western Australia a centre of origin for eastern Australian taxa or is the centre an artefact of a method of analysis? A comment on Hakea and its supposed divergence over the past 12 million years. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 29: 87-94.

McNamara KJ, Scott JK. 1983. A new species of Banksia (Proteaceae) from the Eocene Merlinleigh Sandstone of the Kennedy Range, Western Australia. – Alcheringa 7: 185-193.

Mack CL, Milne LA. 2016. New Banksieaeidites species and pollen morphology in Banksia. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 29: 303-323.

Magallón-Puebla S, Herendeen PS, Crane PR. 1997. Quadriplatanus georgianus gen. et sp. nov.: staminate and pistillate platanaceous flowers from the Late Cretaceous (Coniacian-Santonian) of Georgia, U.S.A. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 158: 373-394.

Maguire TL, Sedgley M, Conran JG. 1996. Banksia Sect. Coccinea (Proteaceae), a new section. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 9: 887-891.

Makinson RO. 1997. New segregate species and subspecies from the Grevillea victoriae (Proteaceae: Grevilleoideae) aggregate from south-east New South Wales. – Telopea 7: 129-138.

Manchester SR. 1986. Vegetative and reproductive morphology of an extinct plane tree (Platanaceae) from the Eocene of western North America. – Bot. Gaz. 147: 200-226.

Manning JC, Brits GJ. 1993. Seed coat development in Leucospermum cordifolium (Knight) Fourcade (Proteaceae) and a clarification of the seed covering structures in Proteaceae. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 112: 139-148.

Martin PG, Dowd JM. 1984. The study of plant phylogeny using amino acid sequences of ribulose-1,5-biphosphate carboxylase. IV. Proteaceae and Fagaceae and the rate of evolution of the small subunit. – Aust. J. Bot. 32: 291-299.

Maslova NP. 2003. Extinct and extant Platanaceae and Hamamelidaceae: morphology, systematics, and phylogeny. – Paleontol. J. 37(Suppl.) 5: S467-S590.

Maslova NP, Herman A. 2004. New finds of fossil hamamelids and data on the phylogenetic relationships between the Platanaceae and Hamamelidaceae. – Paleontol. J. 38: 563-575.

Maslova NP, Herman A. 2006. Infructescences of Friisicarpus nom. nov. (Platanaceae) and associated foliage of the platanoid type from the Cenomanian of Western Siberia. – Palaeontol. J. 40: 109-113.

Maslova NP, Kodrul TM. 2003. New platanaceous inflorescence Archaranthus gen. nov. from the Maastrichtian-Paleocene of the Amur Region. – Paleontol. J. 37: 89-98.

Mast AR. 1998. Molecular systematics of subtribe Banksiinae (Banksia and Dryandra; Proteaceae) based on cpDNA and nrDNA sequence data: implications for taxonomy and biogeography. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 11: 321-342.

Mast AR, Givnish TJ. 2002. Historical biogeography and the origin of stomatal distributions in Banksia and Dryandra (Proteaceae) based on their cpDNA phylogeny. – Amer. J. Bot. 89: 1311-1323.

Mast AR, Thiele K. 2007. The transfer of Dryandra R. Br. to Banksia L. f. (Proteaceae). – Aust. Syst. Bot. 20: 63-71.

Mast AR, Jones EH, Havery SP. 2005. An assessment of old and new DNA sequence evidence for the paraphyly of Banksia with respect to Dryandra (Proteaceae). – Aust. Syst. Bot. 18: 75-88.

Mast AR, Willis CL, Jones EH, Downs KM, Weston PH. 2008. A smaller Macadamia from a more vagile tribe: inference of phylogenetic relationships, divergence times, and diaspore evolution in Macadamia and relatives (tribe Macadamieae; Proteaceae). – Amer. J. Bot. 95: 843-870.

Mast AR, Milton EF, Jones EH, Barker RM, Barker WR, Weston PH. 2012. Time-calibrated phylogeny of the woody Australian genus Hakea (Proteaceae) supports multiple origins of insect-pollination among bird-pollinated ancestors. – Amer. J. Bot. 99: 472-487.

Mast AR, Olde PM, Makinson RO, Jones E, Kubes A, Miller ET, Weston PH. 2015. Paraphyly changes understanding of timing and tempo of diversification in subtribe Hakeinae (Proteaceae), a giant Australian plant radiation. – Amer. J. Bot. 102: 1634-1646.

Matsuo H. 1954. Discovery of Nelumbo from the Asuwa flora (Upper Cretaceous) in Fukui Prefecture in the inner side of Central Japan. – Trans. Proc. Palaeontol. Soc. Jap. 14: 155-158.

Matthews ML, Gardner J, Sedgley M. 1999. The proteaceous pistil: morphological and anatomical aspects of the pollen presenter and style of eight species across five genera. – Ann. Bot. 83: 385-399.

Maynard GV. 1995. Pollinators of Australian Proteaceae. – In: Orchard AE, McCarthy P (eds), Flora of Australia 16, CSIRO, Collingwood, pp. 30-36.

Meeuse ADJ, Ott ECJ. 1962. The occurrence of chlorophyll in Nelumbo seeds. – Acta Bot. Neerl. 11: 227-228.

Mevi-Schutz J, Grosse W. 1988. A two-way gas transport system in Nelumbo nucifera. – Plant Cell Envir. 11: 27-34.

Midgley JJ. 1987. The derivation, utility and implications of a divergence index for the fynbos genus Leucadendron (Proteaceae). – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 95: 137-152.

Miki S. 1927. Über das Verzweigungsmodus und die Blattanordnung des Rhizoms von Nelumbo nucifera, Gaertn. – Bot. Mag. (Tokyo) 41: 522-526. [In Japanese]

Milne LA. 1998. Tertiary palynology: Beaupreaidites and new Conospermeae (Proteoideae) affiliates. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 11: 553-603.

Milne LA, Martin ARH. 1998. Conospermeae (Proteoideae) pollen morphology and its phylogenetic implications. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 11: 503-552.

Mindell RA, Stockey RA, Beard G. 2006. Anatomically preserved staminate inflorescences of Gynoplatananthus oysterbayensis gen. et sp. nov. (Platanaceae) and associated pistillate fructifications from the Eocene of Vancouver Island, British Columbia. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 167: 591-600.

Mindell RA, Karafit SJ, Stockey RA. 2014.

Bisexual flowers from the Coniacian (Late Cretaceous) of Vancouver Island,

Canada: Ambiplatanus washingtonensis gen. et sp. nov. (Platanaceae). – Intern. J. Plant Sci.

175: 651-662.

Moseley MF, Uhl NW. 1985. Morphological studies of the Nymphaeaceae sensu lato XV. The anatomy of the flower of Nelumbo. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 106: 61-98.

Motherwell WDS, Isaacs NW, Kennard O, Bick IRC, Bremner JB, Gillard J. 1971. Bellendine, the first proteaceous alkaloid, a γ-pyronotropane: X-ray structure determination by direct methods. – J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Comm.: 133-134.

Nelson EC. 1978. A taxonomic revision of the genus Adenanthos (Proteaceae). – Brunonia 1: 303-406.

Neubauer HF. 1991. Über die Keimblattknoten einiger Proteaceae. – Beitr. Biol. Pflanzen 66: 33-45.

Ni X-M. 1987. Chinese Lotus. – Scientific Press, Wuhan Research Institute of Botany, Academia Sinica.

Ni X-M. 1989. Recent development with aquatic plants and water gardens in China. – Water Garden J. 5: 36-43.

Nicolson SW, Wyk BE van. 1998. Nectar sugars in Proteaceae: patterns and process. – Aust. J. Bot. 46: 489-504.

Niedenzu F. 1891. Platanaceae. – In: Engler A, Prantl K (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien III(2a), W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 137-140.

Nishikado Y, Miyawaki Y. 1944. Dry rot of lotus roots and arrow-head. – Rep. Ohara Agric. Inst. 36: 365-379.