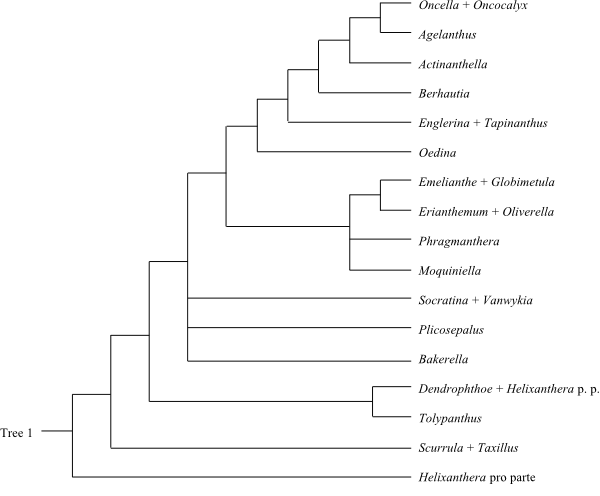

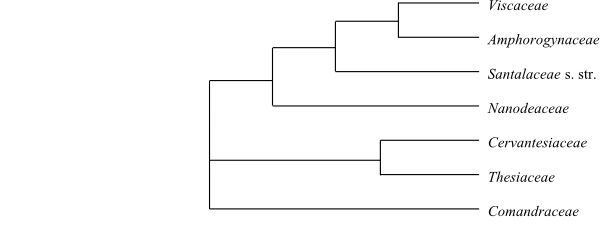

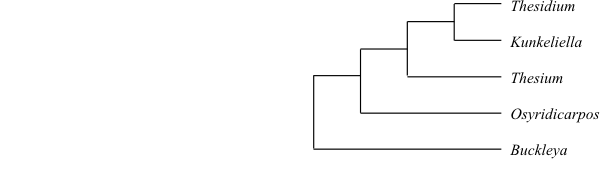

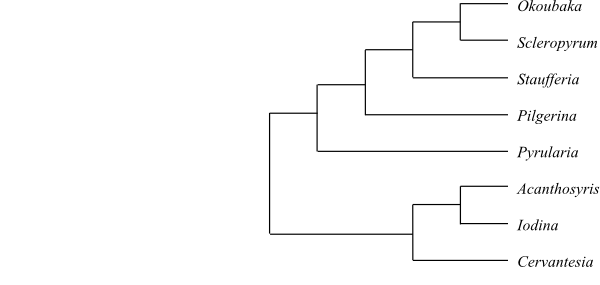

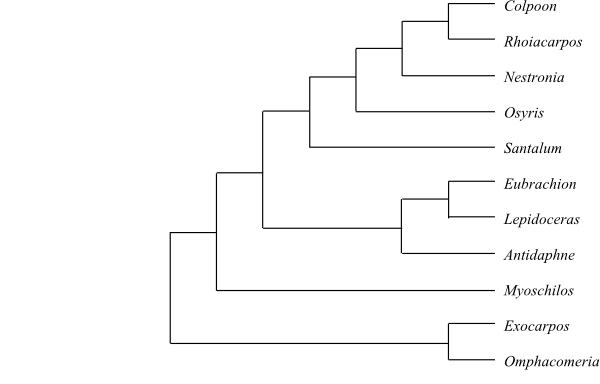

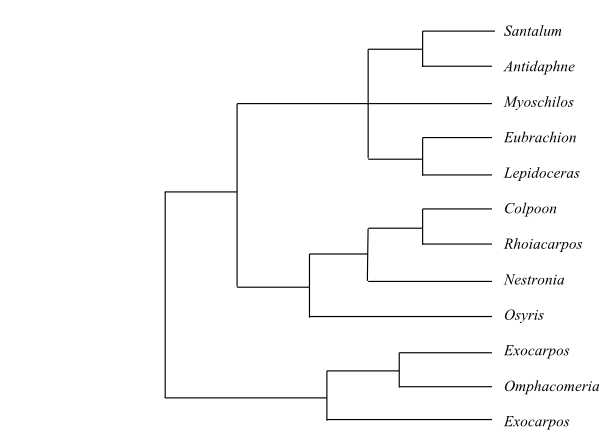

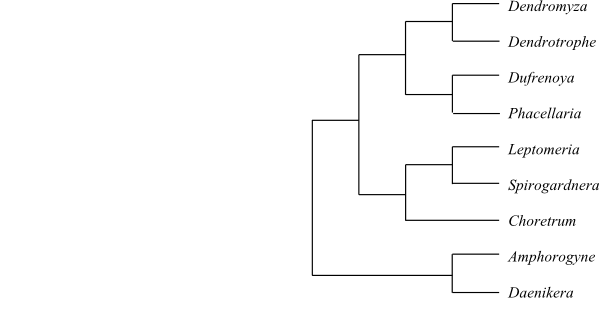

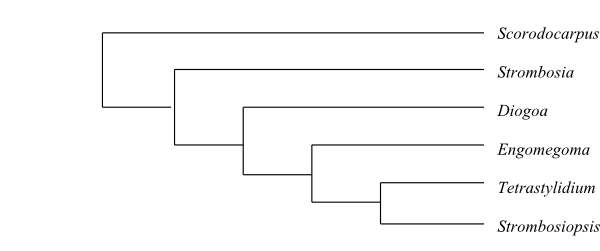

Cladogram of Santalales based on DNA sequence data (Su & al. 2015). The sister-group relationship of Octoknema has not yet been resolved.

[Santalales+[[Berberidopsidales+Caryophyllales]+Asteridae]]

Santalopsida Brongn., Enum. Plant. Mus. Paris: xxix, 115. 12 Aug 1843 [’Santalieae’]; Santalanae Thorne ex Reveal in Novon 2: 236. 13 Oct 1992

Fossils Leaves and reproductive organs are known from the Eocene of North America. Fruits resembling those in Erythropalaceae and Olacaceae have been found in Eocene layers in England. Accuratipollis, Cranwellia and Gothanipollis are fossil pollen grains of the Late Cretaceous and the Cenozoic, which may be assigned to Santalales.

Habit Bisexual, monoecious or dioecious (rarely androdioecious), usually evergreen (sometimes deciduous) trees or shrubs, or perennial herbs (sometimes lianas). Usually root- or stem-hemiparasites (sometimes leafless holoparasites or autotrophic). Sometimes spiny or xeromorphic. Branches sometimes as phyllocladia. Normal roots often absent.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza absent (except, e.g., Ongokea, Coula, and Strombosia). With or without epicortical roots; roots usually modified into intruding and branching haustoria. Root hairs often absent. Granuliferous tracheary elements usually present in haustoria; granules usually consisting of proteins (in, e.g., Ximenia starch). Phellogen ab initio usually subepidermal (sometimes epidermal). Secondary lateral growth usually normal. Vessel elements usually with simple (sometimes scalariform, rarely reticulate or foraminate) perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, scalariform or opposite, simple or bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids, fibre tracheids or libriform fibres with usually simple pits, non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal scanty vasicentric or banded (rarely reticulate, scalariform, aliform, winged-aliform, lozenge-aliform, or confluent), or absent. Sieve tube plastids Ss or S0 type. Pericyclic fibres present or absent. Nodes 1:1, usually unilacunar with one leaf trace (sometimes 3:3, trilacunar with three traces, or ≥5:≥5, multilacunar with five or more traces). Laticifers sometimes present. Secretory cavities present or absent. Schizogenous resiniferous ducts occasionally present. Wood cystoliths absent. Cristarque cells often present. Heartwood often with gum-like substances. Silica bodies often frequent. Prismatic (rhomboidal) calciumoxalate crystals often abundant; druses sometimes present.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate or branched (dendritic, candelabra-shaped or stellate), or absent.

Leaves Alternate (spiral or distichous) or opposite (rarely verticillate), simple, entire, often coriaceous, sometimes isobilateral, sometimes scale-like or modified into spines, with conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle simple or bundle transection arcuate or annular. Venation pinnate, eucamptodromous, brochidodromous, or parallelodromous (rarely acrodromous; leaves sometimes uninerved). Stomata usually paracytic (sometimes anomocytic, anisocytic, parallelocytic or cyclocytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids as platelets, clustered tubuli (sometimes Berberis type, with nonacosan-10-ol as main wax) or annular rodlets, chemically often dominated by palmitone. Lamina often gland-dotted. Epidermal cells often sclerified, with druses, tannins or mucilage. Mesophyll sometimes with sclerenchymatous idioblasts (sometimes with asterosclereids). Cell walls sometimes silicified. Leaf margin usually entire (sometimes serrate).

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, spike-, raceme-, catkin-, umbel-, head- or corymb-like, panicle or fasciculate, spikes, spadices or racemes, or flowers solitary axillary.

Flowers Actinomorphic or zygomorphic. Hypanthium present or absent. Usually epigyny (sometimes hypogynyor half epigyny). Sepals (three to) five or six (to nine), with open, imbricate or valvate aestivation, connate (often reduced to a narrow border on ovary), usually very small or absent. Petals (two to) four to six (to nine; rarely absent), with usually valvate (sometimes imbricate) aestivation, free or more or less connate, often adaxially hairy. Nectaries intrastaminal or extrastaminal or often alternating with stamens. Disc annular (often nectariferous) intrastaminal, extrastaminal or absent.

Androecium Stamens (one to) four to six (to 20), haplostemonous, antepetalous. Filaments usually free from each other (sometimes connate at base), free from or adnate to tepals/petals. Anthers basifixed or dorsifixed, usually non-versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (rarely disporangiate or monosporangiate), introrse, extrorse or latrorse, usually longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits; sometimes poricidal or with one or several short transverse slits; anthers rarely connate into a synandrium). Tapetum secretory. Female flowers often with staminodia.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis usually simultaneous (rarely successive). Pollen grains 3(–19)-colp(or)(oid)ate or 3(–5)-porate (rarely tetraperturate, dipororate to octopororate, or inaperturate), shed as monads, bicellular or tricellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate, with granular, intermediate or columellate infratectum, reticulate, microreticulate, perforate, microperforate or imperforate, striate, scabrate, verrucate, spinulate, echinate, echinulate or smooth.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (one to) three to five (to numerous) connate carpels (carpels rarely absent). Ovary usually inferior (sometimes superior or semi-inferior), unilocular or multilocular. Style single, simple, or stylodia two or three (to five), or absent. Stigmas one to three, lobate or capitate, type? Male flowers often with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation free central or basal (often as a mamelon; sometimes axile or apical, with ovules pendulous from apex of central column) or ovary with undifferentiated placenta with sporogenous tissue, in which one or two megagametophytes develop. Ovules one to numerous per carpel or ovary, usually anatropous (sometimes hemianatropous, or orthotropous), pendulous (rarely horizontal), often apotropous, usually unitegmic or ategmic (rarely bitegmic), tenuinucellar; megasporangium sometimes undifferentiated; ovule often poorly or indistinctly differentiated. Mamelon, spherical structure consisting of basal placenta, megagametophyte and all remaining tissue, sometimes formed by fusion of megasporangium and ovary wall. Micropyle usually endostomal (rarely bistomal). Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type, or disporous, Allium type. Often growth of megagametophyte cells outside ovule, and sometimes for considerable distances within style (e.g. in Olax, many Loranthaceae and Santalaceae). Synergids often with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells one uninucleate or trinucleate, or three uninucleate (sometimes two uninucleate), or absent. Endosperm development ab initio usually cellular (sometimes nuclear, helobial or anomalous). Endosperm haustorium chalazal or formed from lateral endosperm cells. Embryogenesis piperad or irregular and complex. Single megagametophytes sometimes strongly prolonged reaching apex of mamelon (or even stigma at apex of a long style). Embryo often transferred to base of mamelon by development of a prolonged suspensor after fertilization.

Fruit A berry-like fruit with sticky layers of tissue, a nut or a one-seeded drupe with stony mesocarp (rarely a syncarp).

Seeds Seed often surrounded by sticky viscin tissue. Aril absent. Testa and tegmen usually absent (rarely present, crushed). Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, scarce or absent, usually oily (sometimes starchy), with or without chlorophyll. Embryo minute to large, straight, well or little differentiated (sometimes rudimentary), with or without chlorophyll. Cotyledons one, two (rarely up to six) or absent. Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = 5–13

DNA Duplication of the nuclear gene PI. I copy of nuclear gene RPB2 lost. Intron absent from mitochondrial gene coxII.i3 (Comandra).

Phytochemistry Flavonols (quercetin, myricetin), cyanidin, triterpenes, oleanolic acid derivatives, sesquiterpene alcohols, proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins), pyrrolizidine alkaloids as esters of arylic and aralkylic acids, triglycerides of polyacetylenic fatty acids (triglycerides with C18 acetylenic acids, in some clades), long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (e.g. minquartynoic, ximeninic or santalbic acids, in other angiosperms rare or absent), gallic acid, tannins, tyrosine derived cyanogenic glycosides (sambunigrin etc.), triterpene sapogenins, myo-inisitol, quebrachitol, pinitol, and acetylenes present. Saponins rare. Ellagic acid not found.

Systematics Santalales are sister-group to [Asteridae+[Berberidopsidales+Caryophyllales]].

Hemiparasitism is an apomorphy in Santalales. Erythropalaceae, sister to the remaining Santalales, are non-parasitic. Misodendraceae are often recovered as sister-group to [Schoepfiaceae+Loranthaceae], especially in analyses comprising numerous taxa, otherwise often as sister to Schoepfia. The sister-group relationships of the holoparasitic Balanophoraceae are unresolved.

The basal monophyletic groupings in Santalales are characterized entirely by molecular data.

The clade [Ximeniaceae+Aptandraceae+Olacaceae+[Octoknemaceae+[[Loranthaceae+ [Misodendraceae+Schoepfiaceae]]+[Opiliaceae+Santalaceae]]]] has the following potential synapomorphies (Stevens 2001 onwards): root hemiparasites; vessel elements with usually simple perforation plates; axial parenchyma strands seven or more cell layers wide; nodes usually unilacunar with a single leaf trace; petiole and median vein without sclerenchyma fibres; petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate; cuticular thickening present (also in Coulaceae); guard cell chamber small (also in Coulaceae); stomata usually paracytic; some foliar mesophyll and/or epidermal cells silicified; ovules unitegmic (also in Strombosiaceae) or ategmic (in Ximeniaceae usually bitegmic); megagametophyte with chalazal caecum (also in Strombosiaceae) and developed micropylar prolongation.

The clade [[Loranthaceae+[Misodendraceae+Schoepfiaceae]]+[Opiliaceae+Santalaceae]] has, according to Stevens (2001 onwards), guard cell walls not lignified; carpels non-septate; ovules not differentiated, ategmic; testa absent; and endosperm oily, without starch. The [Loranthaceae+ [Misodendraceae+Schoepfiaceae]] clade may have the following synapomorphies: cambium storied; petiole without asterosclereids; epidermal cells sclerified, with druses; calyx minute; and carpels three. Remaining monophyletic groups are characterized by molecular synapomorphies.

|

Cladogram of Santalales based on DNA sequence data (Su & al. 2015). The sister-group relationship of Octoknema has not yet been resolved. |

APTANDRACEAE Miers |

( Back to Santalales ) |

Cathedraceae Tiegh. in Bot. Jahresber. (Just) 25(2): 406. 19 Jan 1900; Chaunochitonaceae Tiegh. in Bot. Jahresber. (Just) 25(2): 406. 19 Jan 1900 [’Chaunochitaceae’]; Harmandiaceae Tiegh. in Bot. Jahresber. (Just) 24(2): 279. 1898

Genera/species 8/33

Distribution Tropical Africa, Madagascar, Indochina, the Malay Peninsula to islands in the Pacific, tropical America.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Usually bisexual (Harmandia and Hondurodendron dioecious), evergreen or deciduous trees or shrubs. At least the majority probably root hemiparasites. Some specis are xerophytes.

Vegetative anatomy Arbuscular mycorrhiza present in Ongokea. Phellogen ab initio subepidermal. Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, simple or bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids or libriform fibres with simple or bordered pits, non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Vascular bundle fibres present in some species. Wood rays uniseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal scanty or in narrow bands (sometimes reticulate, scalariform or aliform). Tyloses sometimes abundant. Vessel elements and/or axial parenchyma sometimes storied. Sieve tube plastids ? type; sieve tube nuclei with non-dispersive protein bodies. Nodes 1:1, unilacunar with one leaf trace. Laticifers present in some species. Cristarque cells sometimes present. Wood ray cells with rhomboidal crystals, without silica bodies. Cystoliths absent. Prismatic calciumoxalate? crystals abundant.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular, simple, or absent.

Leaves Alternate (spiral or distichous), simple, entire, coriaceous, with conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle simple, sometimes with bundle fibres. Venation pinnate, brochidodromous. Stomata paracytic, with small guard cell chamber. Cuticular wax crystalloids usually absent (sometimes present as platelets). Cuticular thickenings present. Lamina often gland-dotted. Epidermal cells with tannins or mucilage. Mesophyll sometimes with sclerenchymatous idioblasts containing sclereids (spicula fibres, present in Cathedra). Asterosclereids often present. Laticifers present in Aptandra, Chaunochiton and Harmandia, otherwise absent. Epidermal and mesophyll cell walls often silicified. Epidermal cells without druses. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Axillary, fasciculate, raceme-, head- or corymb-like panicles, or flowers solitary axillary. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) usually connate.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Hypanthium present or absent. Hypogyny. Sepals four to six, with open or imbricate aestivation, sometimes persistent, usually entirely or almost entirely connate. Petals four to six, usually with valvate (rarely imbricate) aestivation, free or connate at base (in Harmandia connate for most of their length), often with adaxial hairs and/or thickenings. Nectariferous disc extrastaminal (in Aptandra, Harmandia and Ongokea) or intrastaminal (in Phanerodiscus), annular, or absent (in Aptandra as four extrastaminal glands, alternating with stamens).

Androecium Stamens four to six (as many as petals), haplostemonous, antepetalous. Filaments usually free (in Aptandra, Harmandia and Ongokea connate in lower part) and surrounding style, free from or adnate to petals. Anthers dorsifixed or basifixed (anthers in Chaunochiton very short, with each loculus dehiscing by separate slit), often versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (rarely disporangiate), usually extrorse (in Chaunochiton introrse), usually dehiscing by membranous longitudinal slits or valves (in Hondurodendron with three valves; in Anacolosa, Cathedra, Chaunochiton and Phanerodiscus poricidal, dehiscing by apical pores); connective in Cathedra and Phanerodiscus massive. Tapetum secretory. Staminodia usually absent (present in female flowers of Harmandia; in Ongokea often a staminodium-like disc).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tricolpate or tetracolpate (sometimes hexaporate), heteropolar, shed as monads, bicellular or tricellular at dispersal. Apocolpium often concave. Garside’s rule? Exine tectate, with granular, columellate or intermediate infratectum, microperforate or smooth.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of two or three connate carpels; carpels usually septate, usually antesepalous (rarely antepetalous) or median carpel adaxial. Ovary superior, usually bilocular (rarely unilocular or trilocular; sometimes bilocular or trilocular in lower part and unilocular in upper part), with or without ridges. Style single, simple, short to long, or absent. Stigma clavate, capitate, bilobate or trilobate, type? Pistillodium usually absent (present in male flowers of Harmandia).

Ovules Placentation free central (when ovary unilocular) or axile to apical (when ovary at least in upper part bilocular or plurilocular). Ovule one per carpel, anatropous, pendulous, usually unitegmic or ategmic (sometimes bitegmic), tenuinucellar. Integument ? cell layers thick. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Synergids with a filiform apparatus. Endosperm development ab initio usually cellular. Endosperm haustorium chalazal. Embryogenesis?

Fruit A drupe or nut, usually with persistent and strongly accrescent calyx and/or disc etc. (not in Phanerodiscus). Fruit in Phanerodiscus surrounded by a membranous envelope formed from receptacular cupule (not disc cupule). Fruit in Cathedra tightly enclosed by growing disc cupule.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat testal? Testa present. Exotesta? Tegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, oily (and often starchy?). Embryo very small, straight, with chlorophyll? Cotyledons one, two (sometimes fused) or absent. Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = ?

DNA

Phytochemistry Insufficiently known. Alkaloids, cyanogenic compounds, and triglycerides of polyacetylenic fatty acids present. Saponins usually absent. Aluminium accumulated in Cathedra.

Use Fruits, timber.

Systematics Aptandraceae are subdivided into two monophyletic groups (Ulloa Ulloa & al. 2010).

Aptandreae Engl. in H. G. A. Engler et K. A. E. Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. Nachtr.: 145, 146. 2 Aug 1897

5/10. Aptandra (4; A. caudata, A. liriosmoides, A. tubicina, A. zenkeri; tropical Africa, tropical South America), Chaunochiton (3; C. angustifolium, C. kappleri, C. loranthoides; tropical South America), Harmandia (1; H. mekongensis; Indochina, the Malay Peninsula), Hondurodendron (1; H. urceolatum; Honduras), Ongokea (1; O. gore; tropical West Africa). – Pantropical. Filaments connate. Anthers with valvicidal dehiscence. Nectariferous disc extrastaminal. Pollen grains with concave mesocolpium and apocolpium. Calyx accrescent in fruit.

Anacoloseae Engl. in H. G. A. Engler et K. A. E. Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. III, 1: 233, 234. Mai 1889

3/23. Anacolosa (16; tropical Africa, Madagascar, tropical Asia), Cathedra (5; C. acuminata, C. bahiensis, C. grandiflora, C. paraensis, C. rubricaulis; Brazil), Phanerodiscus (2; P. capuronii, P. diospyroidea; Madagascar). – Tropical Africa, Madagascar, tropical Asia, Brazil. Guard cell walls lignified. Anthers with poricidal dehiscence; connective prolonged and massive. Pollen grains diploporate. Disc and/or extradiscal area accrescent in fruit.

|

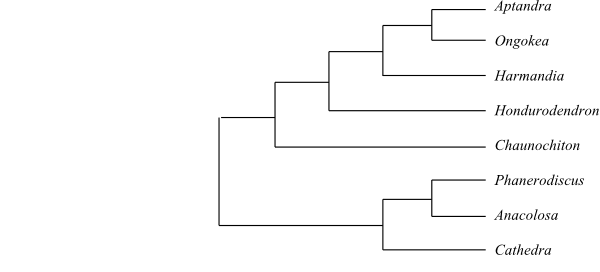

Cladogram of Aptandraceae based on DNA sequence data (Ulloa Ulloa & al. 2010; Nickrent & al. 2010; Su & al. 2015). |

BALANOPHORACEAE L. C. et A. Rich. |

( Back to Santalales ) |

Balanophorales Dumort., Anal. Fam. Plant.: 65. 1829 [‘Balanophorarieae’]; Helosaceae (Schott et Endl.) Bromhead in Mag. Nat. Hist., n.s., 4: 336, 338. Jul 1840 [‘Helosiaceae’]; Lophophytaceae (Schott et Endl.) Bromhead in Mag. Nat. Hist., n.s., 4: 336, 338. Jul 1840; Sarcophytaceae A. Kern., Pflanzenleben 2: 708, 709. 8 Aug 1891; Scybaliaceae A. Kern., Pflanzenleben 2: 708, 709. 8 Aug 1891; Balanophorineae Engl., Syllabus, ed. 2: 108. Mai 1898; Langsdorffiaceae Tiegh. ex Pilger in Engler et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. Nachtr. 4: 76. Apr 1914; Balanophoranae R. Dahlgren ex Reveal in Novon 2: 235. 13 Oct 1992

Genera/species 13–14/41–43

Distribution Tropical and southern Africa, Madagascar, the Comoros, the Himalayas, South and Southeast Asia to Japan, tropical northeastern Australia, New Caledonia, New Zealand, islands in the Pacific, Mexico to tropical and subtropical South America.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Monoecious or dioecious, perennial, whitish, yellow, brown or red, achlorophyllous herbaceous root holoendoparasites with branched or simple subterranean tuber-like structures partly of root nature, partly consisting of host tissue. Succulents.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza absent. Normal roots absent. Stem endogenous. Phellogen absent? Vascular tissue strongly reduced. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessel elements with simple or scalariform perforation plates, or absent. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements? Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma absent? Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes? Calciumoxalate crystals abundant.

Trichomes Epidermal hairs unicellular on tubers (Langsdorffia), simple.

Leaves Usually alternate (spiral or distichous; rarely opposite or verticillate), simple, entire, membranous and scale-like, or absent. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Venation absent. Stomata absent. Cuticular wax crystalloids absent. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal, raceme-, spike- or spadix-like. Inflorescence usually developing endogenously inside tuber (or lobes of tuber; in some genera exogenously). Tuber rupturing during inflorescence development leaving an annular collar-like volva at base of peduncle. Extrafloral nectaries sometimes present on pedicel bases in Balanophora.

Flowers Actinomorphic, usually small to extremely minute (female flowers in Balanophora sometimes consisting of only 50 to 100 cells, resembling an archegonium). Epigyny to half epigyny (hypogyny?). Tepals sepaloid, in male flowers two to four (to eight), in one whorl, with usually valvate (sometimes imbricate) aestivation, free or connate at base, or absent; tepals in female flowers extremely small (sometimes comprising only few cells) or absent.

Androecium Stamens usually three or four (sometimes two; in Sarcophyte and Chlamydophytum sometimes seven or eight), as many as tepals (one or two when perianth absent), antetepalous, free or connate into synandrium, usually free from tepals. Anthers usually free, basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, extrorse, usually longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits; rarely poricidal or with a transversal slit), or connate into a synandrium, irregularly dehiscing. Tapetum secretory? Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis usually simultaneous (in Corynaea successive). Pollen grains usually 3(–5)-colpate, 3(–6)-colporate, or 3(–5)-porate (rarely di- or tripororate, hepta- or octapororate or inaperturate), shed as monads, bicellular or tricellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with usually columellate (sometimes granular) infratectum, usually smooth (rarely microreticulate or finely striate).

Gynoecium Pistil composed of two or three (to five) connate carpels (in Balanophora of seemingly one carpel; in Rhopalocnemis of two transversely orientated), or carpels absent (flowers acarpellate). Ovary inferior or semi-inferior, unilocular. Stylodia two or three (to five), free, or style single, simple or bi- or trilobate (absent in Sarcophyte and Chlamydophytum). Stigmas one to three, more or less widened or capitate to punctate, type? Pistillodium?

Ovules Placentation usually apical (sometimes basal; placenta in Balanophora largely absent). ‘Ovule’ consisting of usually a single megagametophyte per ovary (sometimes several), more or less fused with surrounding pericarp tissue (in Balanophora, Langsdorffia and Thonningia fused with ovary wall), sometimes orthotropous or anatropous, pendulous, ategmic, extremely tenuinucellar. Megagametophyte usually disporous, Allium type (in Balanophora, Langsdorffia and Thonningia monosporous, Polygonum type), often hooked (chalazal caecum sometimes present). Antipodal cells one or two, ephemeral, or absent. Endosperm development usually cellular or nuclear (rarely helobial). One out of two cells formed at first endosperm division not dividing further and possibly corresponding to chalazal endosperm haustorium in other Santalales. Embryogenesis piperad (first zygote division vertical).

Fruit A drupelet, nut or achene, sometimes many together forming a fleshy syncarp.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat sometimes absent. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, oily and starchy or with balanophorins. Embryo short or rudimentary, undifferentiated (four- to twelve-celled), without chlorophyll? Cotyledons absent. Germination via germination tube.

Cytology n = 14, 16?, 18

DNA

Phytochemistry Insufficiently known. Tannins present. Carbohydrates usually stored as starch, yet in Balanophora, Langsdorffia and Thonningia mostly as a wax-like substances, balanophorins (palmitate and lupeol palmitate), especially in tuber. Alkaloids and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Wax for lighting fuel (balanophorin from Balanophora and Langsdorffia), medicinal plants.

Systematics Sarcophyteae are sister-group to the remaining Balanophoraceae.

Sarcophyteae Endl., Gen. Plant.: 73. Aug 1836

2/2. Chlamydophytum (1; C. aphyllum; tropical West Africa), Sarcophyte (1; S. sanguinea; tropical East Africa to Eastern Cape). – Tropical and southern Africa. Stylodia absent.

Helosideae Schott et Endl., Melet. Bot.: 11. 1832 [‘Helosieae’]

6–7/17. Corynaea (1; C. crassa; Central America and the Andes from Costa Rica to Bolivia), Ditepalanthus (2; D. afzelii, D. malagasicus; Madagascar), Helosis (1; H. cayennensis; Mexico, Central America, tropical South America; incl. Exorhopala?), Exorhopala (1; E. ruficeps; northwestern Malay Peninsula; in Helosis?), Ombrophytum (4; O. microlepis, O. peruvianum, O. subterraneum, O. violaceum; western Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, northern Argentina, the Galápagos Islands), Lophophytum (4; L. leandrii, L. mirabile, L. rizzoi, L. weddellii; tropical South America), Scybalium (4; S. depressum, S. fungiforme, S. glaziovii, S. jamaicense; the Great Antilles, Colombia, Ecuador, southeastern Brazil). – Madagascar, the Malay Peninsula, Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, South America. Microsporogenesis in Coronaea successive.

Balanophoreae Engl. in H. G. A. Engler et K. A. E. Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. III, 1: 250, 260. Aug 1889

5/22–24. Rhopalocnemis (1; R. phalloides; India, the Himalayas, southern China, Thailand, Vietnam, West Malesia), Lathrophytum (1; L. peckoltii; Atlantic forests in southeastern Brazil, central Brazil), Lophophytum (3–4; tropical South America), Balanophora (17–19; Congo, Madagascar, the Comoros, tropical Asia to southern Japan, Malesia, tropical northeastern Australia and islands in the Pacific), Langsdorffia (2; L. hypogaea, L. malagasica; Madagascar, New Guinea, Mexico, Central America, tropical South America), Thonningia (1; T. sanguinea; tropical Africa from Senegal to southwestern Ethiopia and south to Zambia). – Pantropical. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type, fused with ovary wall. Balanophorins as storage carbohydrates.

|

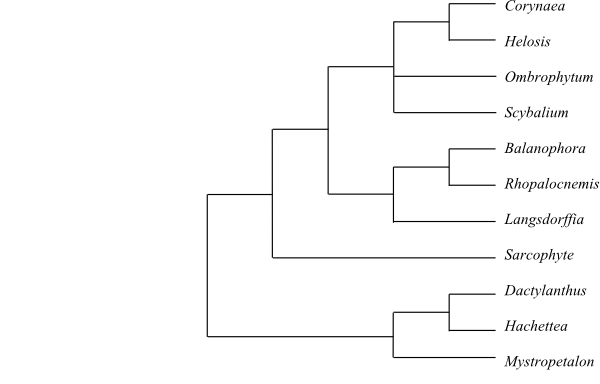

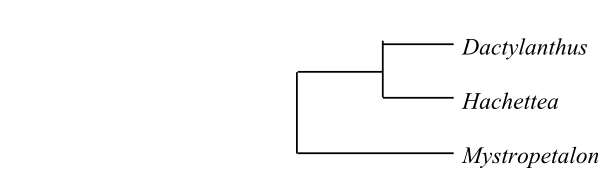

Cladogram of Balanophoraceae based on DNA data (according to Nickrent, The Parasitic Plant Connection website, http://www.parasiticplants.siu.edu/). Dactylanthus, Hachettea and Mystropetalon are now transferred to Mystropetalaceae (Su & al. 2015). |

|

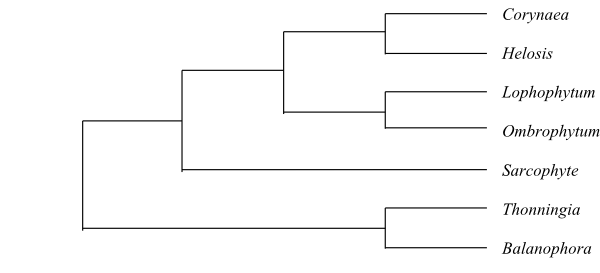

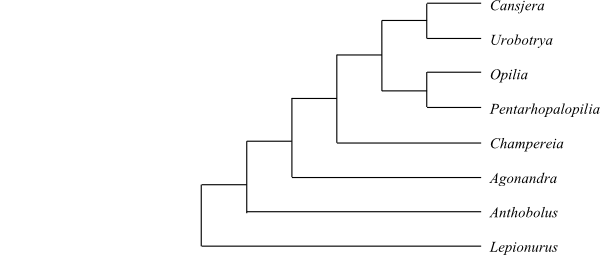

Cladogram of Balanophoraceae based on DNA data (Su & al. 2015). |

COULACEAE Tiegh. |

( Back to Santalales ) |

Genera/species 3/3

Distribution Tropical West Africa, West Malesia, northern tropical South America.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, evergreen trees. Haustoria have never been observed and the three genera are probably non-parasitic.

Vegetative anatomy Arbuscular mycorrhiza present at least in Coula. Phellogen ab initio subepidermal. Vessel elements with simple perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, simple pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform fibres with simple or bordered pits, non-septate. Wood rays multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, paratracheal scanty or in narrow bands. Tyloses (also sclerotic) abundant. Sieve tube plastids ? type; sieve tube nuclei with non-dispersive protein bodies. Nodes 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces. Laticifers, often articulated, present in Minquartia. Wood ray cells without silica bodies. Cystoliths absent. Prismatic calciumoxalate? crystals abundant.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular, or multicellular and dendritic.

Leaves Alternate (spiral), simple, entire, coriaceous, with conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole often swollen distally; petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate or annular. Venation pinnate, eucamptodromous. Stomata paracytic or anomocytic, with small guard cell chamber; guard cell walls not lignified. Cuticular waxes usually absent (sometimes present as platelets). Cuticular thickenings present. Lamina often gland-dotted, often with ‘cork warts’ of stomatal complexes. Epidermal cells with tannins or mucilage, with lignified walls, with druses. Mesophyll with lignified cell walls, without sclerenchymatous idioblasts. Asterosclereids present. Cristarque cells have been reported. Laticiferous canals and schizogenous secretory cavities resiniferous. Cell walls not silicified. Leaf margin entire. Foliar hairs multicellular, dendritic.

Inflorescence Axillary, spike-like thyrse. Peduncles and pedicels usually ferrugineously tomentose.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Hypanthium present or absent. Hypogyny. Sepals usually four or five (rarely three, six or seven), with open or imbricate aestivation, sometimes persistent, almost entirely connate. Petals usually four or five (rarely three, six or seven), usually with valvate (rarely imbricate) aestivation, free or connate at base, usually with adaxial hairs on distal part. Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens usually one to three at each petal (four or five, eight or ten, in Coula twelve or 20), in one to three whorls. Filaments free from each other and from petals. Anthers dorsifixed, often versatile, usually tetrasporangiate, introrse or latrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective usually massive. Tapetum secretory. Staminodia sometimes present.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tricolporate or tetracolporate, shed as monads, bicellular or tricellular at dispersal. Apocolpium convex. Garside’s rule? Exine tectate, without infratectum, smooth or microperforate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (three or) four or five connate carpels; carpels mostly septate, antesepalous, or median carpel adaxial. Ovary superior, trilocular to quadrilocular, with or without ridges. Style single, simple, short to long. Stigma capitate, type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation free central (if ovary unilocular) or axile to apical (if ovary multilocular). Ovule one per carpel, anatropous, pendulous, bitegmic, tenuinucellar? Micropyle ?-stomal. Outer integument five or six cell layers thick. Inner integument five or six cell layers thick. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Synergids with a filiform apparatus. Endosperm development ab initio cellular. Endosperm haustorium chalazal. Embryogenesis?

Fruit A drupe with thin pericarp and lignified endocarp.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa present. Exotesta? Endotesta? Tegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, oily and/or starchy (amyloid). Embryo very small, straight, with chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar?

Cytology n = ?

DNA

Phytochemistry Virtually unknown. Triglycerides of polyacetylenic fatty acids present.

Use Fruits (Coula), timber.

Systematics Minquartia (1; M. guianensis; northern tropical South America), Coula (1; C. edulis; tropical West Africa), Ochanostachys (1; O. amentacea; West Malesia).

Minquartia, Coula and Ochanostachys form an unresolved trichotomy in the analyses by Malécot & Nickrent (2008). On the other hand, Su & al. (2015) recovered Ochanostachys as sister to [Coula+Minquartia].

ERYTHROPALACEAE Planch. ex Miq. |

( Back to Santalales ) |

Erythropalales Tiegh. in Bot. Jahresber. (Just) 25(2): 406. 19 Jan 1900; Heisteriaceae Tiegh. in Bot. Jahresber. (Just) 25(2): 406. 19 Jan 1900; Heisteriales Tiegh. in Bot. Jahresber. (Just) 25(2): 406. 19 Jan 1900

Genera/species 4/c 40

Distribution Tropical West Africa, eastern Himalayas to West Malesia, tropical America.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Usually bisexual (androdioecious in Erythropalum), usually evergreen trees or shrubs (in Erythropalum liana climbing by axillary branch tendrils). At least Erythropalum and Heisteria are autotrophic (haustoria absent).

Vegetative anatomy Arbuscular mycorrhiza present? Phellogen ab initio subepidermal. Medulla with or without diaphragms (in Brachynema septated by diaphragms). Inner side of xylem cylinder in Brachynema provided with distinct grooves. Vessel elements usually with simple or scalariform (sometimes reticulate or foraminate; in Brachynema scalariform) perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, scalariform or opposite (in Brachynema scalariform or opposite), usually simple (sometimes bordered) pits (in Brachynema simple pits or reduced bordered pits). Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids or libriform fibres with simple or bordered pits, usually non-septate. Wood rays multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal scanty or in narrow bands, or absent. Tyloses sometimes abundant. Sieve tube plastids ? type; sieve tube nuclei with non-dispersive protein bodies. Pericyclic fibres present (Brachynema). Nodes usually 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces (in, e.g., Brachynema 5:5, pentalacunar with five traces). Sclereids and sclereid nests present in Brachynema and sometimes forming a continuous layer on outer side of pericycle. Wood with idioblasts containing ethereal oils. Wood cystoliths absent. Cristarque cells present in Brachynema. Wood ray cells without silica bodies. Cortex with or without cristarque cells. Prismatic crystals abundant; druses sometimes present.

Trichomes Hairs usually absent (in Brachynema unicellular; in Maburea multicellular, uniseriate).

Leaves Alternate (spiral or distichous), simple, entire, with conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole in Brachynema with proximal and distal pulvini, and diaphragms with sclereids. Petiole vascular bundle transection annular (sometimes with adaxial plate: vascular cylinder with one or more adaxial or enclosed strands). Venation usually pinnate (lamina three- to five-veined at base; in Erythropalum and Maburea palmate), brochidodromous. Stomata cyclocytic, anisocytic or paracytic, usually with large guard cell chamber. Cuticular waxes? Epidermal cells sometimes with lignified walls, sometimes with druses. Cuticular thickenings present. Cells with tannins or mucilage. Laticifers (often articulated) and idioblastic sclereids present in mesophyll in Heisteria. Cell walls not silicified. Leaf margin usually entire (in Brachynema glandular-serrate).

Inflorescence Axillary, often compound, raceme-like or panicle, or flowers solitary axillary (in Erythropalum large loose slender compound cymose; in Heisteria fascicles; in Maburea often spike-like fascicles; in Brachynema ramiflorous or axillary, fascicular or corymbose). Peduncles sometimes transformed into tendrils. Bracts and floral prophylls (bracteoles) possibly absent in Brachynema.

Flowers Actinomorphic, usually small. Hypanthium absent? Usually hypogyny (in Erythropalum half epigyny). Sepals (three or) four five (or six), small, with valvate aestivation, usually partially connate at base (sometimes absent; in Brachynema connate). Petals (three or) four or five (or six), with valvate aestivation, usually caducous, often connate at base (in Brachynema connate into a tube), often with adaxial hairs. Nectary absent. Disc usually intrastaminal (rarely extrastaminal or absent), entire or lobed, in Heisteria adnate to lower part of ovary.

Androecium Stamens (three or) 4+4 or 5+5, antesepalous and antepetalous, usually twice the number of petals (in Heisteria sometimes inner ones fertile and outer ones staminodial; stamens in Erythropalum as many as petals, often six, haplostemonous; in Brachynema four or five, haplostemonous, antesepalous, alternipetalous). Filaments short, wide, free, usually adnate to petals (epipetalous; in Brachynema adnate to base of perianth tube), with two lateral hairy scales at base. Anthers basifixed to subbasifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective usually massive (in Brachynema prolonged). Tapetum secretory? Staminodia present in Erythropalum and some species of Heisteria.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous? Pollen grains tri- or tetracolpate or tri- or tetracolpor(oid)ate (in Brachynema ramiflorum triporate), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Apocolpium convex. Exine tectate, with granular or columellate infratectum, microperforate or smooth.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of two or three (to five) connate carpels, usually septate, usually antesepalous. Ovary usually superior (in Erythropalum semi-inferior), trilocular (finally often unilocular by disintegration of septa), often with ten ridges. Largest carpels? (stamens?) antesepalous, smallest carpels? (stamens?) antepetalous or odd carpel? (stamen?) adaxial. Style single, simple, very short to long (in Brachynema absent). Stigma capitate or somewhat (bi- or) tri-(to quinque-)lobate, type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation usually apical (in Erythropalum free central). Ovule one per carpel, at least in Maburea anatropous, usually pendulous (rarely horizontal), epitropous?, usually bitegmic (sometimes unitegmic), tenuinucellar. Micropyle usually exostomal. Outer integument ? cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development at least in Strombosia cellular. Endosperm haustorium chalazal? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A one-seeded drupe, often enclosed by persistent and in Brachynema and Heisteria often accrescent calyx; endocarp in Erythropalum dehiscing from apex and downwards into (three to) five or six valves.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed in Brachynema with vertical canals and with vascular strands running down canals. Testa thin. Exotesta? Endotesta? Tegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, occasionally somewhat ruminate, oily and starchy (in Brachynema with yellow globuli consisting of a viscid fat substance). Embryo very small, well differentiated, with chlorophyll? Cotyledons one to six, free or fused (sometimes foliaceous). Radicula long. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 16 (Heisteria parvifolia)

DNA Insertion comprising two to four amino acid triplets (codons) in the 3’-end of the plastid gene rbcL immediately 5’ of the stop codon present in Maburea.

Phytochemistry Virtually unknown. Scopolamine and gallic acid present in Heisteria.

Use Timber.

Systematics Erythropalum (1; E. scandens; eastern Himalayas to Sulawesi and Java), Maburea (1; M. trinervis; Guyana),Heisteria (36; tropical West Africa, tropical America), Brachynema (2; B. axillare: southern Venezuela and northernmost Brazil, Amazonian Peru; B. ramiflorum: central Amazonian Brazil).

Erythropalaceae are sister-group to the remaining Santalales. However, Erythropalaceae have sometimes been recovered as sister to Coulaceae. The leaf anatomy is intermediate between Coulaceae and Aptandraceae and the pollen morphology in Heisteria is similar to that of Coulaceae.

Erythropalum may be basal within Erythropalaceae, and a sister-group relationship between Maburea and Heisteria was recovered by Su & al. (2015). The position of Brachynema is uncertain. However, its wood anatomy is similar to that in Heisteria and molecular data indicate close relationship between Brachynema and Maburea.

LORANTHACEAE Juss. |

( Back to Santalales ) |

Loranthales Link, Handbuch 2: 1. 4-11 Jul 1829 [’Lorantheae’]; Loranthopsida Bartl., Ord. Nat. Plant.: 219, 231. Sep 1830 [’Lorantheae’]; Elytranthaceae Tiegh. in Österr. Bot. Zeitschr. 46: 368. Oct 1896; Nuytsiaceae Tiegh. in Österr. Bot. Zeitschr. 46: 368. Oct 1896; Dendrophthoaceae Tiegh. in Bot. Jahresber. (Just) 24(2): 291. 1898; Treubellaceae Tiegh. in Bot. Jahresber. (Just) 24(2): 291. 1898, nom. illeg.; Gaiadendraceae Tiegh. ex Nakai in Bull. Natl. Sci. Mus. Tokyo 31: 45. Mar 1952 [’Giadendraceae’]; Psittacanthaceae (Horan.) Nakai in Bull. Natl. Sci. Mus. Tokyo 31: 46. Mar 1952

Genera/species c 74/895–915

Distribution Tropical and subtropical regions, with their largest diversity in the Southern Hemisphere, and a few species in temperate parts in the Northern or Southern Hemispheres (southeastern Europe, Japan, New Zealand, temperate South America).

Fossils Leaves have been described from Eocene sediments in Germany and Australia. Ephedrites johnianus, representing shoots with decussately arranged leaves and branches, may also be assigned to Loranthaceae. Fossil pollen are known from Early Eocene onwards (Manchester & al. 2015).

Habit Usually bisexual (rarely dioecious; in Nuytsia monoecious), usually evergreen shrubs (sometimes lianas; Atkinsonia, Gaiadendron and Nuytsia are root parasitic trees) with distinctly sympodial growth. Usually hemiparasites (rarely leafless holoparasites) and stem parasites (although root parasitism is probably a plesiomorphy in Loranthaceae). Some species are hyperparasites on stem hemiparasitic shrubs. Branches rarely transformed into photosynthezising phyllocladia. Shoots rarely resembling Cuscuta (Convolvulaceae) in appearance.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza absent. Normal roots usually absent, modified into primary or secondary haustoria; usually with one or several haustoria in apices of epicortical roots. Phellogen ab initio subepidermal. Secondary lateral growth normal, or anomalous from concentric cambia. Vessel elements with simple perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, scalariform or opposite, simple or bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements short or very short fibre tracheids or libriform fibres usually with bordered pits, non-septate (in Nuytsia also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal scanty vasicentric, or banded. Wood elements often storied. Sieve tube plastids Ss type. Nodes 1:1, unilacunar with one leaf trace. Stem in Nuytsia with gum ducts containing slimy material. Wood cystoliths absent. Cristarque cells often frequent. Silica bodies often abundant. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals often frequent.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate or branched, candelabra-shaped (sometimes dendritic or stellate).

Leaves Usually opposite (rarely spiral or verticillate), simple, entire, usually coriaceous, sometimes isobilateral, rarely scale-like, with ? ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole without asterosclereids. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate? Venation pinnate or parallel, camptodromous or parallelodromous. Stomata usually paracytic (sometimes anomocytic), sometimes with transverse orientation. Cuticular waxes? Epidermal cells sclerified, with druses, tannins or mucilage. Mesophyll sometimes with sclerenchymatous idioblasts (e.g. branched stone cells) containing asterosclereids, etc. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, usually compound raceme-, umbel-, spike- or head-like cymose, or fasciculate of various shape (flowers in Ixocactus solitary). Bract or floral prophylls (bracteoles) often present at base and immediately to one side of ovary.

Flowers Zygomorphic (often slit-monosymmetric) or actinomorphic, often large, often opening explosively. Uppermost part of receptacle together with two connate and often calyculus-shaped floral prophylls? surrounding and adnate to ovary. Epigyny. Sepals (three to) five to seven (to nine), with open aestivation, small, persistent, often reduced, connate (sometimes absent). Petals (three to) five to seven (to nine), with valvate aestivation, free or connate at base into a tube (corolla tube often curved and split on one side). Nectary absent. Disc present or absent.

Androecium Stamens (three to) five to seven (to nine), haplostemonous or diplostemonous, alternisepalous, antepetalous, usually non-septate. Filaments free, usually adnate to petals (epipetalous). Anthers usually basifixed or dorsifixed, versatile or non-versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (rarely di- or monosporangiate), often with septate microsporangia, introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory. Staminodia usually absent (in Passovia rarely three).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tricolpate or tricolporate (rarely tetracolpate or tetracolporate, in Atkinsonia inaperturate), often with fused apertures, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Apocolpium convex (pollen grains sometimes tridentate). Exine tectate, with granular to columellate infratectum, perforate or imperforate, scabrate, verrucate, spinulate, echinate, or smooth.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (one to) three to five (to twelve?) connate carpels. Ovary inferior, unilocular (sometimes seemingly multilocular in lower part). Style single, simple, short to long. Stigma small, type? Pistillodium often present in male flowers.

Ovules Placentation free central or basal (in Lysiana axile). ’Ovules’ four to twelve per carpel, indistinctly differentiated, ategmic, extremely tenuinucellar (integument and megasporangium rudimentary and diffuse). Megasporocytes numerous. Megagametophyte usually disporous, 8-nucleate, Allium type (sometimes monosporous, Polygonum type), developing within a mamelon. Synergids with a filiform apparatus. Megagametophyte sometimes growing to stylar apex (in Moquiniella up to 48 mm long, growing along style way up to stigma and back downwards). Mamelon formed by adnation of megasporangium to ovary wall; mamelon sometimes growing out from ovary base where megagametophyte developes (mamelon sometimes reduced or absent). Endosperm development ab initio cellular, endosperms from all megagametophytes in one ovary developing simultaneously and gradually fusing into a homogeneous mass. ’Hypostase’ formed as a collenchymatous zone below megagametophytes. First division of zygote vertical. Endosperm haustoria developing from basal endosperm cells. Embryogenesis piperad. Polyembryony present.

Fruit Usually a one-seeded (sometimes two- or three-seeded) berry-like or drupaceous fruit (in, e.g., Nuytsia a nut). Mesocarp viscid, with gum in laticifers outside vascular bundles (cf. Santalaceae).

Seeds ’Seed’ covered by sticky viscin tissue, secreted from mesocarp. Aril absent. Testa and tegmen absent. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, scarce or absent (in Aetanthus), oily (and starchy?), formed from several ‘ovules’. Suspensor very long. Embryo large, well differentiated, with chlorophyll, at least sometimes without distinct radicle. Cotyledons two, in many Old World species connate (except at base). Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology x = 8–12, 16

DNA Mitochondrial genes from a hypothetical extinct? root parasitic species of Loranthaceae (with mycorrhiza) may have been uptaken by Botrychium (Ophioglossaceae; in Asia?), perhaps via a common mycorrhizal fungus.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), flavones, dehydroxyflavones, C-glycoflavones, chalcones, cyanidin, ellagic acid (in Nuytsia), gallic acid (in Taxillus), condensed tannins, alkaloids, and rubber (in fruits) present. Tyramine and phenylethylamine often abundant. Saponins and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Medicinal plants, the sticky substance of the fruits used for bird-lime.

Systematics Loranthaceae are sister to [Misodendraceae+Schoepfiaceae].

The three root parasitic genera Nuytsia (southwestern Western Australia), Atkinsonia (eastern Australia) and Gaiodendron (Central and South America) form a basal grade and are successive sister-groups to the remaining Loranthaceae. The stem parasitic genus Notanthera (x = 12) may also be basal.

Nuytsioideae Tiegh. in Bot. Centralbl. 62: 294. 1895

1/1. Nuytsia (1; N. floribunda; southwestern Western Australia). – Root parasitic tree. Unique haustorial behavior occurring: haustoria wearing sclerenchymatous tips functioning as scissors and cutting host root transversely. Leaves spiral. Stomata transversely arranged. Monoecious with bisexual flower central in dichasium and lateral male flowers. Calyculus with vascular bundles. Petals six to eight, free. Stamens six, antepetalous. Fruit a dry three-winged samara (achene). Cotyledons three or four, foliaceous. Germination phanerocotylar. n = 12

Atkinsonia

1/1. Atkinsonia (1; A. ligustrina; the Blue Mountains in New South Wales). – Root parasitic shrub. Axillary raceme with hexamerous (to octomerous) open flowers in monads. Calyculus with vascular bundles. Stamens inserted at two levels on corolla. Anthers dorsifixed, versatile. Fruit a drupe. n = 12

1/1. Gaiadendron (1; G. punctatum; Central and South America). – Tree or shrub. Root parasitic or epiphytic shrub (perhaps root parasite on epiphytes). Racemose or paniculate inflorescences with dichasial partial inflorescences bearing open flowers in triads. Flowers hexamerous (to octomerous). Calyculus with vascular bundles. Stamens inserted at two levels on corolla. Anthers dorsifixed, versatile. Fruit a drupe. Seedling without primary haustoria. n = 12

Loranthoideae Eaton, Bot. Dict., ed. 4: 37. Apr-Mai 1836 [‘Lorantheae’]

c 71/895–915. Stem and branch parasites forming a ’burl’ at insertion point and with epicortical roots running above surface and forming secondary ’burls’. Leaves usually opposite (rarely spiral). Flowers (3–)5–6(–9)-merous. Calyculs usually unvascularized (often absent). Stamens usually biseriate (one whorl sometimes staminodial). Anthers sometimes septate. Megagametophyte disporous, 8-nucleate, Allium type. Fruit a drupe, berry or nut. Endosperm sometimes absent. Embryo plug like (cotyledons sometimes connate). Radicula absent. Primary haustorium present. Germination sometimes cryptocotylar.

Elytrantheae Danser in Verh. Kon. Ned. Akad. Wetensch., Afd. Natuurk., Tweede Sect. 29(6): 4. 1933

14/140–145. Alepis (1; A. flavida; New Zealand), Peraxilla (2; P. colensoi, P. tetrapetala; New Zealand). – Elytranthinae Engl. in Engler et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. Nachtr.: 125. 2 Aug 1897. Amylotheca (5; A. acuminatifolia, A. densiflora, A. dictyophleba, A. duthieana, A. subumbellata; Southeast Asia to New Guinea, tropical Australia, New Caledonia and Vanuatu), Cyne (6; C. baetorta, C. banahaensis, C. monotrias, C. papuana, C. perfoliata, C. quadriangula; the Philippines to New Guinea), Decaisnina (c 25; Java and the Philippines to northern Australia, Tahiti and the Marquesas), Elytranthe (8; eastern India to Vietnam, West Malesia), Lampas (1; L. elmeri; northern Borneo), Lepeostegeres (9; West Malesia to New Guinea), Lepidaria (1; L. tetrantha; southern Thailand, North and West Malesia), Loxanthera (1; L. speciosa; West Malesia), Lysiana (1; L. casuarinae; Australia), Macrosolen (80–85; southern China, South and Southeast Asia to New Guinea, with their highest diversity on Borneo), Thaumasianthes (1; T. amplifolia; the Philippines), Trilepidea (1; T. adamsii; North Island of New Zealand). – Epicortical roots usually present (absent in Lysiana). Flowers bisexual, actinomorphic, usually hexamerous (tetramerous in Alepis and Peraxilla). Anthers usually basifixed (dorsifixed in Alepis and Loxanthera). Placentation in Lysiana axile. x = 12.

Psittacantheae Horan., Char. Ess. Fam.: 86. 17 Jun 1847

17–18/285–290. Central and South America, the West Indies. Epicortical roots present or absent. Partial inflorescences monads, dyads or triads forming spikes, racemes, umbels, or capitula. Flowers actinomorphic, usually bisexual (sometimes unisexual), usually hexamerous (sometimes tetra- or pentamerous). Anthers basifixed or dorsifixed, often dimorphic, in Psittacanthinae with an apiculate connective prolongation. x = 8, 10, 12, 16 – Tristerix, in South America, is pollinated by tree-dwelling marsupials. In Tristerix aphyllus the axis of the seedling degenerates and is replaced by adventitious shoots from the endophyte.

Tupeinae Nickrent et Vidal-Russell in D. L. Nickrent et al., Taxon 59: 546. 4 Apr 2010

1/1. Tupeia (1; T. antarctica; New Zealand). – n = 12.

Notantherinae Nickrent et Vidal-Russell in D. L. Nickrent et al., Taxon 59: 547. 4 Apr 2010

2/2. Desmaria (1; D. mutabilis; Chile from c 38° to c 40°S), Notanthera (1; N. heterophylla; temperate South America). – Temperate South America. n = 12 (Notanthera), n = 16 (Desmaria).

Ligarinae Nickrent et Vidal-Russell in D. L. Nickrent et al., Taxon 59: 547. 4 Apr 2010

2/>13. Ligaria (≥2; L. cuneifolia, L. teretiflora; central Brazil), Tristerix (11; the Andes from Colombia and Ecuador to Chile and Argentina). – South America. n = 10 (Ligaria), n = 12 (Tristerix).

Psittacanthinae Engl. in Engler et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. Nachtr.: 125, 135. 2 Aug 1897

12–13/270–275. Aetanthus (c 15; northern Andes), Cladocolea (c 35; Mexico, Central America, tropical South America), Dendropemon (c 40; the West Indies, with their highest diversity on Hispaniola), Ixocactus (5; I. clandestinus, I. hutchisonii, I. inconspicuus, I. inornus, I. macrophyllus; Colombia, Venezuela), Oryctanthus (14; tropical America; incl. Oryctina?), Oryctina (6; O. atrolineata, O. eubrachioides, O. myrsinites, O. quadrangularis, O. scabrida, O. subaphylla; South America; in Oryctanthus?), Panamanthus (1; P. panamensis; Panamá), Passovia (23; tropical South America), Phthirusa (23; tropical South America), Psittacanthus (57; Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America), Struthanthus (c 50; tropical America), Peristethium (2; P. aequatoris, P. lojae; Costa Rica to northern Bolivia), Tripodanthus (2; T. acutifolius, T. flagellaris; South America). – Tropical America. x = 8.

Lorantheae Rchb., Fl. Germ. Excurs. 1(3): 203. Jul-Dec 1831

c 40/470–480. Tropical regions in the Old World. x = 9 (11)

Ileostylinae Nickrent et Vidal-Russell in D. L. Nickrent et al., Taxon 59: 548. 4 Apr 2010

2/2. Ileostylus (1; I. micranthus; New Zealand, Stewart Island), Muellerina (1; M. celastroides; southeastern Queensland, eastern New South Wales, Victoria). – Southeastern Australia, New Zealand. Epicortical roots present. Raceme- or umbel-like inflorescence consisting of monads or triads. Petals four or five. Anthers basifixed or dorsifixed. x = 11

Loranthinae Engl. in Engler et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. Nachtr.: 125, 127. 2 Aug 1897

2/2. Cecarria (1; C. obtusifolia; the Philippines, Flores, Timor to northeastern Queensland), Loranthus (1; L. europaeus; southeastern Europe). – Europe, North and East Malesia to Queensland. x = 9.

Amyeminae Nickrent et Vidal-Russell in D. L. Nickrent et al., Taxon 59: 548. 4 Apr 2010

c 9/c 110. ’Amyema’ (c 95; Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea and tropical Australia; polyphyletic), Baratranthus (4; B. axanthus, B. mabioides, B. nodiflorus, B. productus; Sri Lanka, West Malesia), Benthamina (1; B. alyxifolia; eastern Queensland, eastern New South Wales), Dactyliophora (3; D. novaeguineae, D. salomonia, D. verticillata; Ceram, New Guinea, northestern Queensland), Diplatia (4; D. alberticii, D. furcata, D. grandibractea, D. tomentosa; tropical Australia), Distrianthes (1; D. molliflora; New Guinea), Helicanthes (1; H. elastica; India), Papuanthes (1; P. albertisii; New Guinea), Sogerianthe (1; S. sogerensis; eastern New Guinea to Solomon Islands). – Tropical Asia to eastern Australia, Solomon Islands. x = 9.

Scurrulinae Nickrent et Vidal-Russell in D. L. Nickrent et al., Taxon 59: 549. 4 Apr 2010

2/c 30. Scurrula (10; southern China, Southeast Asia, Malesia to the Moluccas), Taxillus (c 20; tropical Asia to Central Malesia, one species, T. wiensii, on the coast of Kenya). – Tropical Asia, Kenya. x = 9.

Dendrophthoinae Nickrent et Vidal-Russell in D. L. Nickrent et al., Taxon 59: 549. 4 Apr 2010

4/90–95. Dendrophthoe (c 60; tropical Asia to tropical Australia), ’Helixanthera’ (c 25; tropical Africa, tropical Asia to Sulawesi and the Philippines; non-monophyletic), Tolypanthus (2; T. esquirolii, T. maclurei; India to southeastern China), Trithecanthera (5; T. flava, T. scortechinii, T. sparsa, T. superba, T. xiphostachya; West Malesia). – Tropical regions in the Old World. x = 9.

Emelianthinae Nickrent et Vidal-Russell in D. L. Nickrent et al., Taxon 59: 549. 4 Apr 2010

7/c 70. Emelianthe (1; E. panganensis; eastern and northeastern tropical Africa), Erianthemum (16; eastern and southern Africa), Globimetula (13; tropical Africa), Moquiniella (1; M. rubra; Northern, Western and Eastern Cape), Oliverella (3; O. bussei, O. hildebrandtii, O. rubroviridis; eastern and south-central Africa), Phragmanthera (34; tropical Africa to Namibia, the Arabian Peninsula), Spragueanella (1; S. rhamnifolia; eastern and south-central Africa). – Tropical and southern Africa, the Arabian Peninsula. x = 9.

Tapinanthinae Nickrent et Vidal-Russell in D. L. Nickrent et al., Taxon 59: 550. 4 Apr 2010

14/165–170. Actinanthella (2; A. menyharthii, A. wyliei; southeastern and southern Africa), Agelanthus (c 60; Africa, the Arabian Peninsula), Bakerella (16; Madagascar), Berhautia (1; B. senegalensis; Senegal, Gambia), Englerina (c 25; tropical Africa), Oedina (2; O. erecta, O. pendens; Tanzania, northern Malawi), Oncella (2; O. ambigua, O. curviramea; tropical East Africa), Oncocalyx (11; eastern and southern Africa, the Arabian Peninsula), Pedistylis (1; P. galpinii; southern Mozambique, Swaziland, northeastern South Africa), Plicosepalus (11; arid and semiarid regions in eastern and southern Africa), Septulina (2; S. glauca, S. ovalis; southern Namibia, Northern and Western Cape), Socratina (1; S. bemarivensis; southwestern Madagascar), Tapinanthus (33; tropical and southern Africa, one species also in northern Yemen), Vanwykia (1; V. remota; eastern and southeastern Africa). – Africa, Madagascar, the Arabian Peninsula. x = 9.

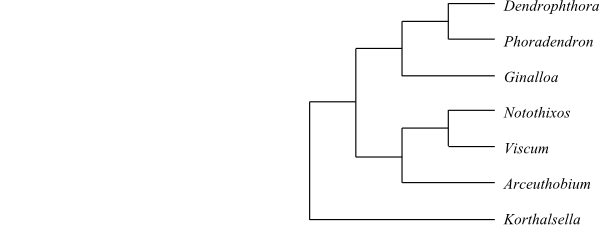

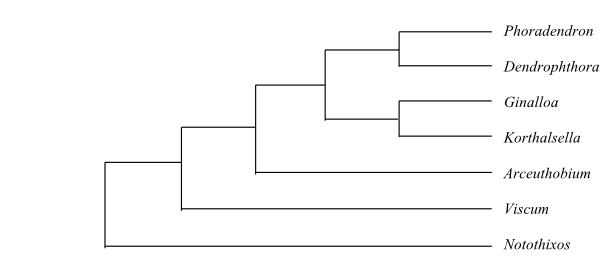

|

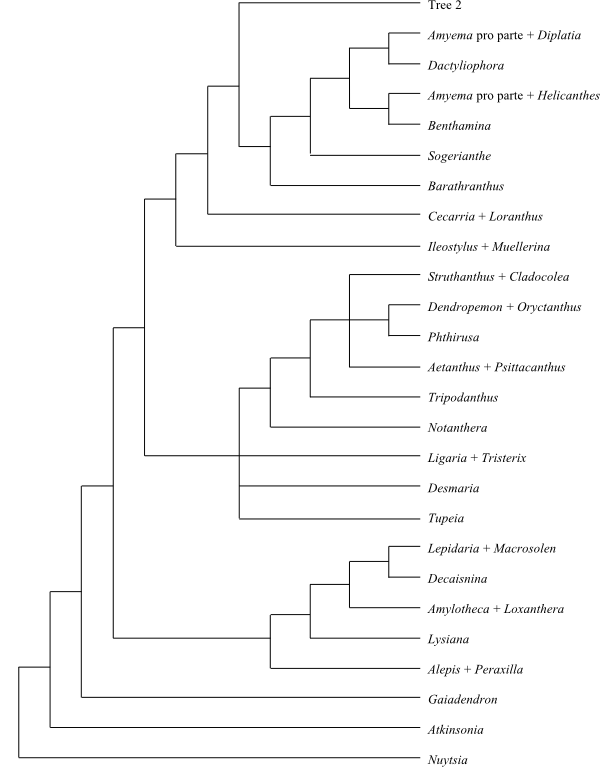

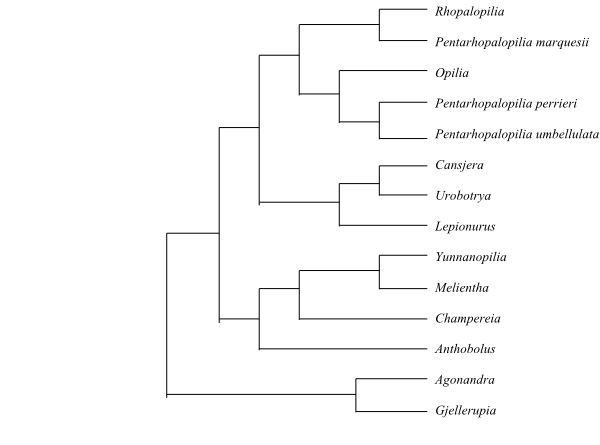

Cladogram (simplified) of Loranthaceae based on DNA sequence data (Nickrent & al. 2010). |

|

Majority rule consensus tree 1 of a Bayesian analysis of Loranthaceae based on DNA sequence data (Vidal-Russell & Nickrent 2008). |

|

Majority rule consensus tree 2 of a Bayesian analysis of Loranthaceae based on DNA sequence data (Vidal-Russell & Nickrent 2008). |

MISODENDRACEAE J. Agardh |

( Back to Santalales ) |

Genera/species 1/8

Distribution Southern Chile and adjacent parts of Argentina.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Usually dioecious (rarely bisexual or monoecious), evergreen shrubs with distinct sympodial growth and even as young a thick stem. Stem/branch hemiparasites almost exclusively on Nothofagus (Nothofagaceae). Branches coarse. Stem apex aborting annually, one or several lateral branches continuing the sympodial vegetative growth the following year.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza absent. Normal roots absent. Roots modified into haustoria; haustorial region radially expanding. Phellogen ab initio subepidermal? Primary medullary rays narrow, uniseriate. Secondary lateral growth normal or anomalous from concentric (successive) cambia; sometimes an inner secondary cylinder of bundle-like fascicular areas. Vessel elements very short, with simple perforation plates; lateral pits alternate to almost scalariform, simple or bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary elements libriform fibres usually with simple pits, non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays absent or consisting of fibres or thin-walled cells. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse, with fusiform cells. Vessel elements, fibres and/or axial parenchyma storied. Sieve tube plastids S0 type, without starch or protein inclusions. Nodes probably 1:1, unilacunar with one leaf trace. Wood ray cells without silica bodies. Wood without cystoliths. Parenchyma with calciumoxalate crystals.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular.

Leaves Alternate (spiral), simple, entire, often coriaceous, sometimes scale-like, with ? ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Foliar dimorphism occurring: leaves on floral shoots different from leaves on vegetative shoots. Petiole without asterosclereids. Petiole vascular bundles? Venation pinnate, camptodromous. Stomata usually paracytic (sometimes anomocytic). Cuticular waxes? Cystoliths present. Epidermal cells sclerified (with druse?)? Cell walls often silicified. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Axillary, raceme-, catkin- or spike-like (sometimes compound) with pubescent pedicels. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) present or absent.

Flowers Actinomorphic, very small. Possibly hypogyny (to slightly half epigyny). Tepals absent in male flowers; tepals in female flowers three, in one whorl, with open aestivation, sepaloid, reduced, connate at base. Nectariferous disc intrastaminal, annular, lobate.

Androecium Stamens two or three, haplostemonous, antepetalous. Filaments free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, disporangiate (monothecal), introrse, dehiscing by short apical tangential slits. Tapetum secretory? Staminodia in female flowers short, bristle-like, alternitepalous, each inserted in furrow in ovary (to one side of tepal attachment point), persistent and accrescent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous? Pollen grains (3–)4–12(–19)-porate, shed as monads, ?-cellular at dispersal. Apocolpium convex. Exine intectate, acolumellate, with granular, psilate-scabrate and echinate endexine beset with scattered spinulae.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of three connate carpels. Ovary possibly superior (or slightly semi-inferior), unilocular, with three furrows. Style single, simple, very short, stout. Stigma trilobate, type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation free central. Ovules three per ovary, orthotropous, pendulous, ategmic, tenuinucellar. Megasporangium indistinctly defined. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development cellular. Endosperm haustorium chalazal, elongate. Embryogenesis complex, unusual type.

Fruit A dry, one-seeded, nut-like fruit (sometimes a samara), inserted at three strongly accrescent, plume- or bristle-like staminodia, each one inserted at a furrow in ovary to other side of perianth base. Setae of pistillate flower elongating following anthesis to become elongated plume-like organs 10–85 mm long and covered by numerous uniseriate trichomes (setae in some species with hooked apex); these organs possibly modified stamens alternating with three perianth segments.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat sparsely sclereidal. Testa and tegmen absent. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious to sparse, oily, or absent. Embryo small to large, straight, with chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, connate. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = ?

DNA

Phytochemistry Unknown.

Use Unknown.

Systematics Misodendrum (8; cold-temperate Chile and Argentina from 33°S to Magellan’s Strait).

Misodendrum is sister to Schoepfiaceae.

Antidaphne possibly belongs in Misodendraceae (here provisionally placed in Santalaceae). The cotyledons in Antidaphne probably have three vascular strands.

The wood anatomy of Misodendrum resembles that in Loranthaceae (Carlquist 1985).

MYSTROPETALACEAE J. D. Hooker |

( Back to Santalales ) |

Genera/species 3/3

Distribution Southwestern South Africa, North Island of New Zealand, mountains on New Caledonia.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Monoecious or dioecious, perennial, yellow, brown or red, achlorophyllous herbaceous root holoendoparasites with branched or simple subterranean tuber-like structures partly of root nature, partly consisting of host tissue. Succulents.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza absent. Normal roots absent. Stem endogenous. Phellogen absent? Vascular tissue strongly reduced. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessel elements with simple or scalariform perforation plates, or absent. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements? Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma absent? Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes? Calciumoxalate crystals abundant.

Trichomes Epidermal hairs unicellular, simple.

Leaves Usually alternate (spiral or distichous; rarely opposite or verticillate), simple, entire, membranous and scale-like, or absent. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Venation absent. Stomata absent. Cuticular wax crystalloids absent. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal, raceme-like. Inflorescence usually developing endogenously inside tuber (or lobes of tuber; in some genera exogenously). Tuber rupturing during inflorescence development leaving an annular collar-like volva at base of peduncle. Male inflorescence branches of first order on elongated upper part of stem, subtended by bracts (male inflorescence branches of first order in Dactylanthus inserted on slightly swollen apical part of stem, not subtended by bracts). Female flower single on thin elongated branch of first order. Extrafloral nectaries?

Flowers Usually actinomorphic (in Mystropetalon zygomorphic), very small. Epigyny to half epigyny. Tepals sepaloid, in male flowers usually three (in Dactylanthus two filiform or absent), in one whorl, with usually valvate (sometimes imbricate) aestivation, free or connate at base, or absent; tepals in female flowers three, very small, connate and cupuliform, persistent, inserted on an articulate pedicel later becoming a cushion-like elaiosome. Floral parts in Dactylanthus and Hachettea surrounded and more or less covered by peduncle bracts. Nectariferous disc somewhat lobed (Mystropetalon).

Androecium Stamens one or two, antetepalous, free or connate into synandrium, usually free from tepals (in Mystropetalon adnate to lower part of adaxial tepals). Anthers usually free, basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, extrorse (in Mystropetalon finally introrse), usually longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits; rarely poricidal or with a transversal slit), or connate into a synandrium, irregularly dehiscing. Tapetum secretory? Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis usually simultaneous. Pollen grains usually 5–12(–15)-colpate, in Dactylanthus and Hachettea annulate and (3–)4(–5)-angular, shed as monads, bicellular or tricellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with usually columellate (sometimes granular) infratectum, usually smooth (rarely microreticulate or finely striate).

Gynoecium Pistil composed of two or three connate carpels, or carpels absent (flowers acarpellate). Ovary inferior or semi-inferior, adnate to calyx tube, basally encircled by irregularly crenate disk, usually unilocular (in Mystropetalon bilocular or trilocular). Style single, simple. Stigmas one to three, capitate?, type? Male flowers in Mystropetalon with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation apical. ‘Ovule’ consisting of usually a single megagametophyte per ovary (sometimes several; in Mystropetalon one per carpel), more or less fused with surrounding pericarp tissue, sometimes orthotropous or anatropous, pendulous, ategmic, extremely tenuinucellar. Megagametophyte usually disporous, Allium type, often hooked (chalazal caecum sometimes present). Antipodal cells one or two, ephemeral, or absent. Endosperm development usually cellular or nuclear (rarely helobial). One out of two cells formed at first endosperm division not dividing further and possibly corresponding to chalazal endosperm haustorium in other Santalales. Embryogenesis piperad (first zygote division vertical).

Fruit A drupelet, nut or achene (in Mystropetalon surrounded by fleshy perianth and basal disc-like elaiosome consisting of modified pedicel).

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat sometimes absent. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, oily and starchy or with balanophorins. Embryo short or rudimentary, undifferentiated (four- to twelve-celled), without chlorophyll? Cotyledons absent. Germination via germination tube.

Cytology n = 14, 16?, 18

DNA

Phytochemistry Insufficiently known. Tannins present (in Mystropetalon reddish-brown mystrin). Carbohydrates usually stored as starch, balanophorins (palmitate and lupeol palmitate), especially in tuber. Alkaloids and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Medicinal plants.

Systematics Mystropetalon (1; M. thomii; Western Cape), Dactylanthus (1; D. taylorii; North Island of New Zealand), Hachettea (1; H. austrocaledonica; New Caledonia). – New Caledonia, New Zealand. – The haustoria in Mystropetalon are provided with stolons which may form additional haustoria with graniferous tracheary cells. The flowers in Mystropetalon are epigynous and the pollen grains are cuboid with a pore in each of the eight corners.

Mystropetalaceae are sister-group to Balanophoraceae.

Monoecious, arising from subspherical lobed tuber. Peduncle imbricately leaved. Inflorescence spicate, lower part with female flowers, upper male flowers. Flowers slightly zygomorphic, subtended by one bract and two prophylls. Male flowers with thre perianth segments valvately arranged and two distinct stamens. Anthers dorsifixed, lengthwise dehiscing. Pollen grains (9-)12(-15)-colpate and (3)4(5)-angular. Disk short, lobed, encircling a rudimentary pistil. Female flowers inserted on an articulate pedicel later to become a cushion-like elaiosome. Perianth segments three. Staminodes two, ovary inferior, obviously trimerous. Style single, basally encircled by crenate disk. Fruit almost spherical, with hard exocarp and soft endocarp. Parasite on Leucadendron and Protea.

Dioecious, arising from spheroid tuber. Basal sheath not obvious. Peduncle covered by spiraly arranged scaly leaves which in upper third gradually become larger and function as bracts each subtending one inflorescence branch. Flowers subtended by short, reduced bracts, male flowers pedicellate. Tepals three, elliptic, valvate. Stamens two with very shorty filaments. Anthers terminal, dehiscing by transverse slits. Pollen grains asymmetric or centrosymmetric, (3)4(6)-porate-annulate. Female flowers sessile, perianth very small, superior, short tubular trilobate. Ovary inferior, narrowly ovoid, apparently three-celled. Style single. Parasite on Cunoniaceae.

Dioecious, arising from a large, irregularly lobed tuber. Basal sheath not obvious. Flowering shoots often more than 20 at a time from large tubers, with spirally arranged imbricate scaly leaves which increase in size distally in inflorescence and form an involucre around the flower-bearing branches, these 15-25, ebracteate, inserted at swollen apical part of peduncle, each with up to 50 male or 100 female flowers. Male flowers usually ebracteate, sessile. Tepals usually two, lateral. Stamen single with short and thick filament. Anther deeply lobed quadrilocular, dehiscing irregularly. Pollen grains asymmetric or centrosymmetric, (3-)10-11-porate-annulate. Female flowers sessile. Tepals two minute, linear. Ovary inferior, apparently two-celled. Style single. Parasite on many different families.

|

Cladogram of Mystropetalaceae based on DNA data (according to Nickrent, The Parasitic Plant Connection website at http://www.parasiticplants.siu.edu/, and Su & al. 2015) |

OCTOKNEMACEAE Solereder |

( Back to Santalales ) |

Genera/species 1/≥14

Distribution Tropical Africa.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Dioecious, evergreen trees or shrubs. Probably root hemiparasites. Some representatives are xerophytes.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio epidermal. Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits opposite, simple pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform fibres with simple or bordered pits, septate or non-septate. Wood rays multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma usually absent (rarely diffuse). Sieve tube plastids ? type; sieve tube nuclei with non-dispersive protein bodies. Nodes ≥5:≥5, at least pentalacunar with five or more leaf traces. Wood ray cells without silica bodies. Cystoliths absent. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals frequent.

Trichomes Hairs stellate to peltate.

Leaves Alternate (spiral or distichous), simple, entire, coriaceous, with conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection annular. Venation pinnate, camptodromous. Stomata anisocytic or cyclocytic, with closed small guard cell chamber. Cuticular waxes? Cuticle thickenings occurring. Lamina often gland-dotted. Epidermal cells with tannins or mucilage. Mesophyll without sclerenchymatous idioblasts. Asterosclereids present. Cristarque cells present. Cell walls not silicified. Prismatic crystals abundant. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Axillary, few-flowered, fasciculate, male flowers in raceme or flowers solitary, female flowers in simple spike.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Hypanthium present or absent. Epigyny. Sepals strongly reduced, with open or imbricate aestivation, sometimes persistent, usually entirely or almost entirely connate, or absent. Petals five, with valvate aestivation, free or connate at base (rarely largely connate?), often with adaxial hairs. Nectariferous disc lobate, with lobes alternating with stamens (male flowers) or staminodia (female flowers).

Androecium Stamens as many as petals, antepetalous. Filaments free from each other, free or adnate to petals. Anthers dorsifixed to basifixed, often versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (rarely disporangiate), introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective usually massive. Tapetum secretory. Female flowers with staminodia.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains tricolporate or tetracolporate, shed as monads, bicellular or tricellular at dispersal. Apocolpium convex. Garside’s rule? Exine tectate, with granular and/or columellate infratectum, microperforate or smooth.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of usually three (sometimes four) connate carpels. Ovary inferior, usually trilocular (sometimes quadrilocular) in lower part and unilocular in upper part. Style single, simple, short. Stigma trilobate to quinquelobate, each lobe further divided (expanded stigmatic excrescences), type? Male flowers with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation free central. Ovule one per carpel, anatropous, unitegmic or bitegmic, tenuinucellar. Micropyle ?-stomal. Integument ? cell layers thick. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Synergids with a filiform apparatus? Endosperm development usually cellular. Endosperm haustorium chalazal? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A drupe, often with persistent perianth. Endocarp laminated (with six to ten thin intrusions into seed furrows).

Seeds Aril absent. Testa present. Exotesta? Endotesta? Tegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, ruminate, oily and starchy. Embryo very small, straight, with chlorophyll? Cotyledons often six. Radicula elongated. Germination phanerocotylar, epigaeous.

Cytology n = ?

DNA

Phytochemistry Insufficiently known. Alkaloids, saponins, cyanogenic compounds, tannins (phenylpropanoids), triglycerides of polyacetylenic fatty acids present. Aluminium accumulated.

Use Fruits.

Systematics Octoknema (≥14; tropical Africa).

Octoknema is sister-group to the clade [[Loranthaceae+[Misodendraceae+Schoepfiaceae]]+[Opiliaceae+Santalaceae]] (Nickrent & al. 2010).

Octoknema is sister-group to all Santalales except Strombosiaceae and Erythropalaceae (Nickrent & al. 2010; Su & al. 2015). The wood anatomy resembles that in Ximeniaceae.

OLACACEAE Juss. ex R. Br. |

( Back to Santalales ) |

Olacales Mirb. in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp. Regn. Veg.: 40. Sep-Oct. 1835 [’Olacineae’]

Genera/species 2–3/45–50

Distribution Tropical and southern Africa, Madagascar, Indomalesia, Australia, New Caledonia;tropical South America.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Usually bisexual (in Olax rarely monoecious or dioecious), evergreen trees or shrubs (rarely lianas). Olax (including ‘Dulacia’?) and Ptychopetalum are root hemiparasites. Some species are xerophytes. Branches in Olax sometimes strongly quadrangular (with wing-like edges).

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza absent. Phellogen ab initio subepidermal. Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, simple and bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids or libriform fibres with simple or bordered pits, non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal scanty or in relatively narrow bands. Sieve tube plastids ? type; sieve tube nuclei with non-dispersive protein bodies. Nodes in Olax usually 1:1, unilacunar with one leaf trace, in Ptychopetalum (and ‘Dulacia’) 3:3, trilacunar with three traces. Cystoliths absent. Silica bodies often abundant, also in wood ray cells. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals often abundant.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or absent.

Leaves Alternate (spiral or distichous; rarely opposite), simple, entire, coriaceous, with conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle simple. Venation pinnate, brochidodromous. Stomata paracytic or anomocytic, with small guard cell chamber. Cuticular wax crystalloids usually absent (sometimes present as platelets). Cuticular thickenings present. Lamina often gland-dotted. Epidermal cells with tannins or mucilage. Mesophyll without sclerenchymatous idioblasts (spicula fibres). Asterosclereids absent. Epidermal and mesophyll cell walls often silicified. Cristarque cells have been reported. Cell walls often silicified. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Axillary, panicle, raceme- or head-like, or flowers solitary axillary. Bracts usually caducous (sometimes persistent and foliaceous).

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Hypanthium present or absent. Hypogyny to half epigyny. Sepals (four or) five or six, with open or imbricate aestivation, sometimes persistent, usually entirely or almost entirely connate (sometimes absent). Petals (three to) five or six, with valvate aestivation, connate at base or to half of their length, with adaxial hairs and in Olax sometimes a membranous ligule between filament base and petal. Nectary? Disc intrastaminal, annular or cupulate (absent in Ptychopetalum).

Androecium Stamens usually three to six (in Ptychopetalum up to ten or twelve), as many as or twice the number of petals, in one or two whorls, alternisepalous or antesepalous, alternipetalous or antepetalous (larger stamens antesepalous, smaller stamens antepetalous). Filaments free from each other, adnate to petals. Anthers dorsifixed or basifixed, often versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (rarely disporangiate), introrse, usually longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits, rarely apically); connective usually massive. Tapetum secretory. Staminodia three to six, bifid or bilobate, or absent (three or five outer stamens in Olax sometimes staminodial; three outer stamens in Ptychopetalum staminodial).