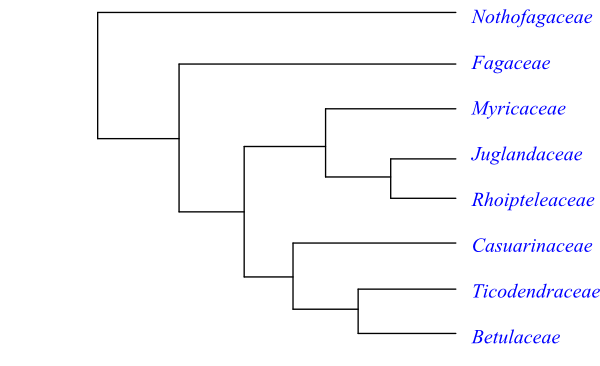

Cladogram of Juglandales based on DNA sequence data. The sister-group relationships between Myricaceae, Juglandaceae and Rhoiptelea are uncertain. Nothofagus and Fagaceae are – as usually found – successive sisters to the remaining Juglandales.

[Polygalales+[Rosales+[Cucurbitales+Juglandales]]]

Fagales Engl., Syllabus, ed. 1: 94. Apr 1892; Juglandanae Takht. ex Reveal in Novon 2: 236. 13 Oct 1992; Faganae Takht., Divers. Classif. Fl. Pl.: 146. 24 Apr 1997

Fossils Records from the mid-Cenomanian represent the oldest known fossils of presumed Juglandales. The group seems to have reached its peak of diversity during the Santonian to the Campanian, according to the wide range of Normapolles fossils, and inflorescences, flowers and pollen grains of Juglandales are fairly abundant from the Turonian onwards. Antiquacupula sulcata from the Late Santonian of Georgia (USA) includes hexamerous epigynous bisexual and male flowers and fruits resembling Fagaceae and Nothofagus. The tepals are inserted in two series with three tepals in each and the androecium is arranged in two whorls with six stamens each andAntiquacupula probably had nectaries at the filament bases. The pollen grains are tricolporate and the three carpels are biovular. Up to six flowers are surrounded by a pedunculate quadrilobate cupule. Archaefagacea futabensis from the Early Coniacian of Japan is represented by bisexual epigynous hexamerous flowers and fruits consisting of three carpels. The pollen grains are tricolpate with a striate exine and the carpels are biovular. The trilocular fruits are three-seeded.

The Normapolles complex comprises fossil tricolporate (rarely tripororate) oblate or suboblate pollen grains with granular infratectum. The apertures are strongly thickened and often formed through infratectal extensions, and the polar areas may be intectate. The exine surface is smooth to rugulate or finely spinulate. They are known from the mid-Cenomanian to the Oligocene, being most diverse in the Santonian to the Campanian and in the Eocene from eastern North America eastwards through Europe to western Siberia. Normapolles pollen is associated with usually bisexual hexamerous flowers or fruits of Antiquocarya, Bedellia, Budvaricarpus, Calathiocarpus, Caryanthus, Dahlgrenianthus, Endressianthus, Manningia and Normanthus in Juglandales. Of these, Dahlgrenianthus is hypogynous and Endressianthus and perhaps Bedellia are unisexual. The perianth and androecium are uniseriate. The stamens are alternitepalous in Endressianthus and Normanthus, otherwise antetepalous. The fruit is a nut. Caryanthus, from Late Cretaceous strata in Europe and perhaps eastern North America, are bisymmetrical epigynous quadritepalous flowers with six to eight stamens producing tricolporate pollen grains. The bicarpellate gynoecium has a unilocular ovary and two free styles. Caryanthus and Budvaricarpus are similar to extant Rhoiptelea chiliantha.

Endressianthus, described from the Campanian to the Maastrichtian of Portugal, comprises male and female compound cymes, epigynous flowers with bicarpellate gynoecium, nuts with single-seeded locules and other reproductive structures. The perianth is reduced and the number of stamens is four or less. The pollen grains have three endopores each grain with six exopores arranged in pairs, and the apertural areas are interconnected by crests. The Late Cretaceous Normanthus, likewise from Portugal, comprises bisexual pentapetalous flowers, alternipetalous stamens, two collateral carpels with separate and relatively long styles, and possibly parietal placentation.

Habit Usually monoecious or dioecious (rarely bisexual, andromonoecious, polygamodioecious or polygamous), evergreen or deciduous trees or shrubs. Buds with spiral scales.

Vegetative anatomy Ectomycorrhiza abundant. Root nodules with nitrogen fixing actinobacteria (at least two different Frankia clades responsible for nitrogen fixation in Juglandales; also Frankia species restricted to Juglandales). Frankia infection via root hairs. Phellogen ab initio superficially or deeply seated (sometimes outer-cortical). Primary vascular tissue cylinder, without separate vascular bundles. Vessel elements with simple or scalariform (rarely reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform, opposite, intermediary or alternate, simple or bordered pits. Vestured pits often present. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids or fibre tracheids (sometimes libriform fibres) with simple or bordered pits, usually non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates or banded, or paratracheal scanty, vasicentric, aliform, confluent, reticulate, scalariform, unilateral or banded, or absent. Sieve tube plastids S type; sieve tubes with non-dispersive P-protein bodies. Nodes usually 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces (sometimes 1:1, unilacunar with one trace, rarely 5:5, pentalacunar with five traces). Bark cells with sclereids and rhomboid crystals. Bark often rich in tannins. Secretory cells present or absent. Heartwood sometimes with gum-like substances. Silica bodies rarely present. Prismatic or rhomboid calciumoxalate crystals often frequent in parenchyma cells.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, simple or branched (sometimes dendritic, fasciculate, stellate, peltate or lepidote, rarely vesicular or T-shaped); glandular hairs, also peltate-lepidote, often present (sometimes secreting ethereal oils and resins).

Leaves Alternate (spiral or distichous, sometimes verticillate), usually simple (sometimes pinnately compound), entire (sometimes scale-like), usually with conduplicate to plicate, involute or curved ptyxis. Stipules intrapetiolar, scale-like, caducous (sometimes absent); leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate or annular. Venation pinnate, craspedodromous, semicraspedodromous or camptodromous. Stomata anomocytic, cyclocytic or paracytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Domatia as pockets or hair tufts, or absent. Epidermis with or without mucilaginous idioblasts. Sometimes enlarged epidermal cells containing ethereal oils. Lamina sometimes with resinous glands (colleters). Leaf margin sinuous, dentate, serrate, biserrate or entire; leaf teeth sometimes cunonioid or modified urticoid (secondary veins proceeding to non-glandular teeth, higher-order veins converging on urticoid teeth).

Inflorescence Terminal or lateral, usually compound cymose spicate, catkin-like or capitate inflorescence, consisting of dichasia (flowers sometimes solitary). Bracts more or less connate into scales and/or reduced, often persistent and sometimes accrescent in fruit. One or several female dichasia often enclosed by lignified cupule, modified shoot consisting of sterile inflorescence parts.

Flowers Actinomorphic, minute. Epigyny (very rarely hypogyny). Tepals in male flowers one to seven (to nine), with imbricate aestivation, scale-like, sepaloid, free or more or less connate, in one or two whorls, or absent; in female flowers indistinct or absent. Nectary absent. Disc usually absent. Flowers often fused into pseudanthia.

Androecium Stamens one or four to eight (to more than 100), in one (antetepalous) or several whorls. Filaments free or more or less connate, free from or adnate at base to tepals, sometimes partially or entirely divided. Anthers basifixed or dorsifixed, usually non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, extrorse (sometimes introrse?), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory. Staminodia usually absent (sometimes six to twelve).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains (2–)3(–7)-por(or)ate, polypantopor(or)ate or 3(–4)-colpor(oid)ate (sometimes stephanocolpate, rarely di- or hexacolpate; with cavity, vestibulum, between outer and inner pore), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate or granular infratectum, microperforate, striate, scabrate, rugulate, verrucate, spinulate, microechinate or psilate. Arci (band-shaped arches) of thick sexine running between pores. Pollen tube growth often interrupted (irregularly or periodically).

Gynoecium Pistil composed of two to six (to 15) more or less connate carpels. Ovary inferior, unilocular to trilocular (to 15-locular). Stylodia usually two to six (to nine), free or connate at base. Stigmas two (or three), capitate, punctate or adaxially decurrent, linear, papillate or non-papillate, Dry type. Pistillodium usually absent (male flowers sometimes with pistillodium).

Ovules Placentation axile, apical or basal. Ovules one or two per carpel (or locule), usually anatropous or orthotropous (sometimes campylotropous, rarely hemianatropous), ascending or pendulous, epitropous, bitegmic or unitegmic, crassinucellar, immature at pollination. Micropyle endostomal. Archespore sometimes multicellular. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Synergids sometimes with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells sometimes multiplicative. Fertilization usually delayed; chalazogamy frequently occurring. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis asterad or onagrad.

Fruit A one-seeded nut, often a samara, often densely surrounded by more or less connate and sometimes lignified bracts and/or floral prophylls, or a unilocular to trilocular calybium.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa vascularized, sometimes adnate to pericarp. Exotesta often enlarged and persistent. Tegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm thin or absent. Embryo large, straight, well differentiated, oily, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, often large. Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology x = (7) 8–16

DNA Plastid gene infA lost/defunct. Mitochondrial intron coxII.i3 lost.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), dihydroflavonols, biflavonoids, flavones, flavanones, flavononols, lipofilic flavonoids, cyanidin, delphinidin, ethereal oils, resins, and balsam (with O- and C-methylated flavones), catechin, tetracyclic and pentacyclic triterpenes (of taraxerane, ursane and lupane type), ellagic and gallic acids, hydrolyzable tannins (ellagotannins and galloyltannins), non-hydrolyzable tannins, proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins), naphthoquinones, stilbenes, citrullin, and often shikimic and quinic acids present. Alkaloids and cyanogenic compounds rare. Saponins not found.

Systematics Juglandales are sister-group to Cucurbitales.

Nothofagus (Nothofagaceae) is sister to the remaining Juglandales, characterized by the common features: spiral leaves; and dorsifixed anthers, according to Stevens (2001 onwards). A plausible topology is the following: [Fagaceae+[[Myricaceae+[Juglandaceae+Rhoipte-leaceae]]+[Casuarinaceae+[Ticodendraceae+Betulaceae]]]]. Moreover, the clade [[Myri-caceae+[Juglandaceae+Rhoipteleaceae]]+[Casuarinaceae+[Betulaceae+Ticodendraceae]]] (descendants of the fossil Normapolles complex) has the following potential synapomorphies: chambered crystals in axial parenchyma; pollen grains pororate; exine consisting of two layers separated by alveolar zone and expanded around apertures; pistil composed of two connate carpels; and chalazogamy.

The clade [Myricaceae+[Juglandaceae+Rhoipteleaceae]] is characterized by the features (Stevens 2001 onwards): chains of crystal-containing cells present in wood; absence of P-protein bodies in sieve tubes; presence of aromatic peltate glandular hairs; absence of stipules; one flower per bract; stigma lamellular/laciniate; ovule one per ovary, orthotropous. Furthermore, the leaf teeth in Juglandaceae, Rhoipteleaceae and Myricaceae are intermediary, with apex extended (outwards/inwards) and non-glandular, and leaf tooth vein united with vein branches running below or above leaf tooth; tepals sometimes with three traces; and varying number of integuments. Juglandaceae and Rhoipteleaceae share the characteristics: imparipinnate leaves; four tepals; endosperm absent; and x = 16.

The clade [Casuarinaceae+[Ticodendraceae+Betulaceae]] has the following potential synapomorphies (Stevens 2001 onwards): pollen grains with rows of spinulae; Pollen tubes branched; stigmas elongate; and presence of dihydroflavonols (?). Betulaceae and Ticodendraceae share the features: sclereid nests in bark, cells with rhomboidal crystals; presence of mucilage cells; leaves distichous; and anther thecae separate or almost separate.

|

Cladogram of Juglandales based on DNA sequence data. The sister-group relationships between Myricaceae, Juglandaceae and Rhoiptelea are uncertain. Nothofagus and Fagaceae are – as usually found – successive sisters to the remaining Juglandales. |

BETULACEAE S. F. Gray |

( Back to Juglandales ) |

Corylaceae Mirb., Elém. Phys. Vég. Bot. 2: 906. 24-30 Jun 1815 [‘Corylacées (Corylaeae)’], nom. cons.; Carpinaceae Vest, Anleit. Stud. Bot.: 265, 280. 1818 [‘Carpinoideae’]; Corylales Dumort., Anal. Fam. Plant.: 11. 1829 [‘Corylarieae’]; Betulales Rich. in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp. Regn. Veg.: 17. Sep-Oct 1835 [‘Betulineae’]; Carpinales Döll, Fl. Baden 2: 536. med. 1858 [’Carpineae’]

Genera/species 6/c 140

Distribution Temperate and polar regions on the Northern Hemisphere and southwards to northern Argentina, North Africa, Himalaya, Indochina and Sumatra.

Fossils The oldest fossil representative of Betulaceae is Palaeocarpinus from the Paleocene and Eocene of Europe and North America. It comprises leaves, male flowers and fruits surrounded by spiny involucral bracts. Numerous Cenozoic Betulaceae are known, including Alnus, Betula, Corylus and Ostrya, and the fossil Asterocarpinus and Cranea.

Habit Monoecious, usually deciduous (rarely evergreen) trees or shrubs. Horizontal lenticels often abundant.

Vegetative anatomy Alnus has root nodules with nitrogen fixing actinobacteria (Frankia); cluster roots often present. Phellogen ab initio superficially or deeply seated (sometimes outer-cortical). Primary vascular tissue cylinder, without separate vascular bundles. Vessel elements with usually scalariform (sometimes simple) perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform, opposite or alternate, usually bordered (rarely simple) pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids and/or fibre tracheids with usually simple pits, non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays usually uniseriate, usually homocellular, often aggregated. Axial parenchyma usually apotracheal diffuse, diffuse-in-aggregates or banded (sometimes paratracheal scanty, reticulate or banded, or absent). Secondary phloem usually stratified into hard fibrous and soft parenchymatous layers. Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces. Heartwood sometimes with resinous? substances. Bark cells with sclereid and rhomboid calciumoxalate crystals. Prismatic crystals abundant.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate, simple; glandular hairs present, also peltate-lepidote.

Leaves Alternate (spiral or distichous), simple, entire, usually with conduplicate (sometimes plicate) ptyxis. Stipules intrapetiolar, scale-like, caducous; leaf sheath absent. Colleters present. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate. Venation pinnate, craspedodromous. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Epidermis with or without mucilage cells. Domatia as pockets or hair tufts. Lamina sometimes with resinous glands (colleters). Leaf margin biserrate; leaf teeth modified urticoid.

Inflorescence Terminal or lateral, compound catkin-like or multi-flowered capitate groups, consisting of dichasia (female flowers in Corylus solitary). Up to five bracts (sometimes peltate) more or less connate into scales and/or reduced, often persistent (in Alnus lignified) in fruit (female flowers in Betula three per bract). Pseudanthium in Ostrya consisting of three flowers with approx. 15 pairs of divided stamens in total. Prophyll in Alnus adaxial.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Epigyny (sometimes very distinct). Tepals in male flowers one to six, sepaloid, or absent (perianth in Corylus reduced to ridge-like structure); tepals in female flowers indistinct or absent. Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens (one to) four (to six to twelve?), in one whorl, antesepalous. Filaments filiform, sometimes partially or entirely split, free or more or less connate, free from or adnate at base to tepals. Anthers basifixed? or dorsifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, extrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective shorter than anther. Tapetum secretory. Staminodia usually absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains 3(–7)-por(or)ate, starchy, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with granular infratectum, microperforate, scabrate to somewhat rugulate. Pollen tube branching.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of two (or three) connate carpels. Ovary inferior, unilocular in upper part, bilocular (or trilocular) in lower part. Stylodia two (or three), rarely connate at base. Stigmas papillate or non-papillate, Dry type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation apical-axile. Ovules one or two (to four) per carpel, usually collateral (sometimes superposed), usually anatropous (in Corylus campylotropous), pendulous, usually unitegmic (in Carpinus bitegmic), crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal (Carpinus). Outer integument ? cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Lower part of integument vascularized. Parietal tissue one or two, or four to eight cell layers thick. Nucellar cap one or two cell layers thick or absent. Archespore usually multicellular (sometimes unicellular). Megagametophytes several. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Chalazogamy. Endosperm development nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis asterad.

Fruit A single-seeded nut, often a two-winged samara (in Alnus in lignified cone-like infructescence); nut often densely surrounded by more or less connate bracts and floral prophylls (bracteoles).

Seeds Aril absent. Testa? Tegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm thin or absent. Embryo large, straight, well differentiated, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, small, oily. Germination phanerocotyl or cryptocotyl.

Cytology x = (7) 8, 11, 14

DNA Horizontal transfer of mitochondrial gene rps11.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), flavones, lipofilic flavonoids, cyanidin, delphinidin, ellagic acid, and triterpenes (pentacyclic triterpenes in bark, pentacyclic and tetracyclic triterpenes in leaves) present. Alkaloids and cyanogenic compounds not found. Nitrogen transported as citrullin.

Use Ornamental plants, fruits (nuts from Corylus), timber, carpentry, charcoal, brushes and besoms, birch bark (Betula).

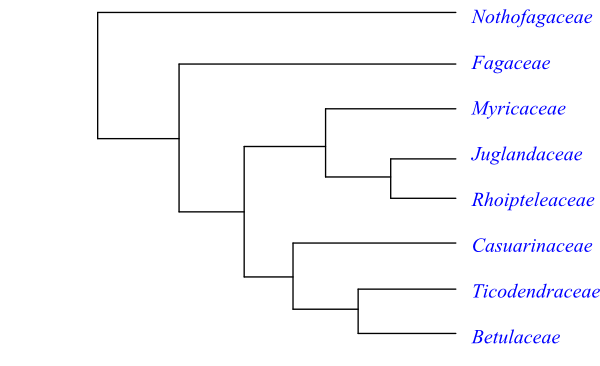

Systematics Betulaceae are sister-group to Ticodendron (Ticodendraceae).

Betuloideae Rich. ex Arn., Botany: 131. 9 Mar 1832 [‘Betulineae’]

2/c 70. Betula (c 35; temperate, boreal and polar regions on the Northern Hemisphere south to Southeast Asia), Alnus (c 35; temperate, boreal and polar regions on the Northern Hemisphere, mountains in tropical America). – Temperate and cold regions on the Northern Hemisphere, southwards to mountain areas in South America. Vessel elements without spiral thickenings. Peltate glandular hairs present. Female flowers usually without tepals (tepals sometimes two). Parietal tissue one or two cell layers thick. Nucellar cap approx. two cell layers thick. Infructescence with lignified or scale-like bracts separate from fruit. Nutlet samaroid, flat.

Coryloideae Hook. f., Stud. Fl. Brit. Isl.: 343. 1870 [‘Coryleae’]

4/c 70. Corylus (18; temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere), Ostryopsis (3; O. davidiana, O. intermedia, O. nobilis; eastern Mongolia, northern to southwestern China), Carpinus (c 40; temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere, Southeast Asia, mountains in Central America), Ostrya (9; temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere south to Central America). – Temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere, Southeast Asia, Central America. Vessel elements with spiral thickenings. Tracheids present. Dichasium (cymule) with one or two flowers. Male flowers without tepals. Female flowers with indistinct tepals. Filaments hairy. Integuments approx. six cell layers thick. Suprachalazal tissue massive. Parietal tissue four to eight cell layers thick. Nucellar cap one or two cell layers thick or absent. Megagametophyte sometimes with chalazal caecum. Infructescence with foliaceous bracts and accrescent foliaceous floral prophylls (bracteoles). Nuts large, not or little flattened.

|

Cladogram of Betulaceae based on DNA sequence data and morphology (Chen & al. 1999). |

CASUARINACEAE R. Br. |

( Back to Juglandales ) |

Casuarinales Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 261. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Casuarineae’]; Casuarinanae (Lindl.) Takht. ex Reveal et Doweld in Novon 9: 549. 30 Dec 1999

Genera/species 4/95–100

Distribution Madagascar, Malesia to New Guinea, Melanesia, Australia, with their largest diversity in Australia.

Fossils Pollen grains from the Early Paleocene have been found in New Zealand, and Paleocene to Miocene pollen fossils of Casuarinaceae are known from Australia, South Africa, Argentina and the Ninetyeast Ridge in the Indian Ocean. Wood, inflorescences and infructescences are recorded from Neogene layers onwards.

Habit Monoecious or dioecious, evergreen trees or shrubs with narrow furrowed Equisetum-like photosynthesizing branches. Most species are xerophytes.

Vegetative anatomy Root nodules containing nitrogen fixing actinobacteria (Frankia). Higher order rootlets clustered, with limited growth (proteoid roots). Branch furrows usually deep and closed (in Gymnostoma shallow and open). Phellogen ab initio deeply seated. Vessel elements with simple or scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits alternate or opposite, bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids with simple or bordered pits, non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, heterocellular (often compound; sometimes absent). Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or banded, or paratracheal scanty, vasicentric, scalariform. Tyloses sometimes abundant. Sieve tube plastids S type, with starch grains and non-dispersive P-protein bodies. Nodes 1:1, unilacunar with one leaf trace. Stomata tetracytic or paracytic, usually hidden inside closed longitudinal branch furrows perpendicular to length axis of branch (in Gymnostoma exposed). Cuticle thick, with crystalline bodies resembling inverted mushrooms. Heartwood often with resinous substances. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals abundant.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, simple or branched (often dendritic).

Leaves Verticillate (four to c. 20 per whorl), simple, entire, minute and scale-like, membranous, fused with nearest internode and forming longitudinal ridges, with ? ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Venation reduced. Stomata sparse, tetracytic or paracytic, or absent, often hidden. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Male flowers in one or several spicate inflorescences; female flowers in axillary? verticillate capitate inflorescences, cone-like in fruit. Bracts more or less developed, scale-like, connate at base; each bract subtending one flower and two scale-like floral prophylls (bracteoles), in fruit strongly accrescent and lignified.

Flowers Actinomorphic, very small. Tepals in male flowers one or two, scale-like, caducous at anthesis; tepals absent in female flowers. Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamen one. Filament inflexed in bud, free from tepals. Anther basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse?, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective shorter than anther. Tapetum secretory. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous? Pollen grains (2–)3(–5)-por(or)ate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with granular infratectum, microperforate, scabrate, spinulate or rugulate. Pollen tube branching.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of two carpels connate in lower part; usually only abaxial carpel fertile (in Gymnostoma both carpels fertile). Ovary usually unilocular (pseudomonomerous; rarely bilocular). Stylodia two, long, filiform, connate at base, winged in lower part in fruit. Stigmas two, long, decurrent, collateral, non-papillate, Wet type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation axile (basal at maturation). Ovules two per carpel, orthotropous (or anatropous?), ascending, epitropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal. Outer integument three or four cell layers thick. Inner integument two or three cell layers thick. Suprachalazal tissue massive. Parietal tissue five to seven cell layers thick. Megasporangium sometimes with tracheids (vascular bundle branched in chalaza). Archespore multicellular. Several to numerous megasporocytes formed at cell division resulting in two to more than 20 megagametophytes. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type, with chalazal caecum. Chalazogamy. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A single-seeded samara surrounded by two lignified floral prophylls (bracteoles); adjacent ovaries connate into syncarps?; fruit liberated when enlarged floral prophylls separate from each other. Infructescence cone-like, with lignified bracts.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa adnate to pericarp, vascularized? Tegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm absent. Embryo one or often several (polyembryony), straight, well differentiated, oily, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two, large, oily and proteinaceous. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 8 (Gymnostoma) to 14 – Agamospermy sometimes occurring.

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), biflavonoids, flavones, cyanidin, catechin, pentacyclic triterpenes, ellagic acid, ellagitannins, and proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins) present. Myricetin, alkaloids, saponins, and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Ornamental plants, timber (very hard wood), stabilization of sandy areas (Casuarina equisetifolia, etc.).

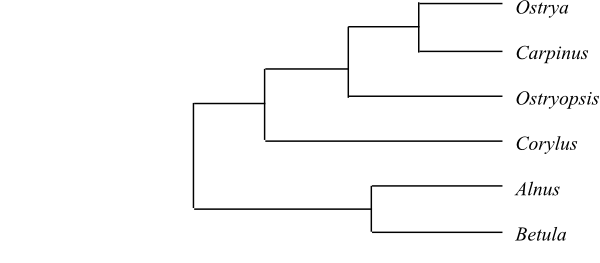

Systematics Gymnostoma (18; Malesia to islands in western Pacific), Ceuthostoma (2; C. palawanense: Palawan; C. terminale: Borneo, Halmahera, New Guinea), Casuarina (17; Southeast Asia and eastwards to islands in the western Pacific), Allocasuarina (c 60; Australia).

Casuarinaceae are sister to [Ticodendraceae+Betulaceae].

Gymnostoma is sister to the remaining Casuarinaceae.

|

Cladogram (simplified) of Casuarinaceae based on DNA sequence data (Sogo & al. 2001). |

FAGACEAE Dumort. |

( Back to Juglandales ) |

Quercaceae Martinov, Tekhno-Bot. Slovar: 525. 3 Aug 1820 [’Quercoides’]; Quercales Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 228. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Quercinae’]

Genera/species 8–10/590–875

Distribution Southern Canada to northwestern South America and Cuba, temperate parts of Europe and Southwest Asia, the Mediterranean, the Himalayas, East Asia to the Russian Far East and Japan, Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea.

Fossils The oldest known flowers of Fagaceae are from the Santonian and fossilized wood is recorded from the Maastrichtian of Mexico. Protofagacea allonensis from the Late Santonian of Georgia in the United States is represented by inflorescences, pollen, fruits and epigynous flowers with six tepals and twelve stamens or three carpels. The cupule is quadrilobate. Fossils from the Cenozoic include a large number of wood, leaves, flowers, pollen and fruits in the Northern Hemisphere. Trigonobalanus is known from the Paleocene to the Oligocene of North America.

Habit Usually monoecious (rarely dioecious), evergreen or deciduous trees or shrubs.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio superficial. Vessel elements with simple or scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits opposite, intermediary or alternate, usually simple (sometimes bordered) pits. Vestured pits present. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform fibres? (fibre tracheids?) with simple or bordered pits, usually non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays usually uniseriate (sometimes multiseriate), homocellular or somewhat heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse, diffuse-in-aggregates, or banded, or paratracheal scanty, vasicentric, aliform, confluent, reticulate, or unilateral, or absent. Wood elements sometimes storied. Tyloses abundant. Tile cells present in some species. Secondary phloem often? stratified into hard fibrous and soft parenchymatous layers. Sieve tube plastids S type, with non-dispersive P-protein bodies. Nodes 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces. Sclereid nests with rhomboid crystals present in bark. Parenchyma sometimes with oil cells and/or mucilage cells. Parenchyma cells sometimes with prismatic calciumoxalate crystals.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate or multiseriate, simple or branched, capitate, fasciculate or stellate; glandular hairs?

Leaves Usually alternate (spiral or distichous, rarely verticillate), simple, entire or lobed, often coriaceous, with conduplicate-plicate ptyxis. Stipules usually caducous; leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection annular. Venation pinnate, craspedodromous? (camptodromous when leaf margin entire). Stomata anomocytic or cyclocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Domatia as hair tufts (comata) or absent. Lamina sometimes gland-dotted? Epidermis with or without mucilaginous idioblasts. Hydathodes sometimes present. Leaf margin sinuate, serrate, biserrate or entire.

Inflorescence Axillary, with male flowers solitary or two to c. 30 together in compound, often branched spicate, catkin-like or capitate inflorescence. Female flowers in distichous one- to three-flowered (to seven-flowered) dichasia, each one or several together surrounded by entire or bilobate to more than octalobate cupule, modified shoot consisting of sterile inflorescence parts, on outer side scaly, prickly or with other types of processes, lignified and sometimes stipitate. Cupule with sclereids, crystals and tannins; cupule lobes supernumerary (one more than number of fruits). Female flowers inserted at base of male inflorescence or in specialized axillary inflorescences. Flowers with numerous stamens interpreted as pseudanthia, formed by fusion of dichasia. Presence of extrafloral nectaries reported from leaf buds in species of Quercus.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Epigyny. Tepals (sepals?) (four to) six (to nine; sometimes absent), with imbricate aestivation, scale-like, usually more or less connate, in one or two whorls. Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens four to c. 20 (to more than 90), antesepalous and/or alternisepalous. Filaments filiform, usually free from each other, free from tepals. Anthers dorsifixed or subbasifixed, versatile?, tetrasporangiate, extrorse?, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective rarely prolonged. Tapetum secretory. Staminodia six to twelve or absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains tricolporate or tricolporoidate (rarely tetracolporate), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate agranular or granular infratectum, striate, anastomosingly striate, scabrate, verrucate, verruculate, rugulate, microrugulate or smooth. Pollen tubes usually branched.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (two or) three to six (in Lithocarpus up to 15) connate carpels; carpels alternitepalous or median carpel abaxial. Ovary inferior, (bilocular or) trilocular to sexalocular (to 15-locular), at least in lower part. Stylodia two to six (to nine), entirely or almost entirely free. Stigmas two to six (to nine), capitate, punctate or adaxially decurrent, often with apical pore, non-papillate, Dry type. Male flowers often with pistillodium (in Trigonobalanus as hair tuft, coma).

Ovules Placentation apical to axile. Ovules two per carpel (or locule), anatropous to hemianatropous, pendulous, usually bitegmic (rarely unitegmic), crassinucellar. Micropyle bistomal (Fagus) or endostomal? Outer integument ? cell layers thick, vascularized. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Suprachalazal tissue massive. Parietal tissue one, four or five cell layers thick. Nucellar cap approx. two cell layers thick. Megasporangium sometimes with tracheids. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type, with lateral or basal chalazal caecum, into which secondary megagametophyte nucleus migrates and becomes fertilized. Synergids sometimes with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells in Castanea multiplicative. Porogamy or chalazogamy. Endosperm development usually nuclear (rarely cellular). Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis onagrad. Fertilization very delayed.

Fruit A unilocular to trilocular nutlet, calybium (sometimes with several secondary septa), rounded, two- or three-angular or winged; fruits surrounded by bivalvular to quadrivalvular, often spiny cupule (possibly modified inflorescence; valves possibly modified partial inflorescences). Pericarp tanniniferous, with lignified outer layer. Endocarp usually hairy on inner side.

Seeds Seed pachychalazal. Aril absent. Testa? Tegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm absent. Embryo large, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, usually not plicate, starchy (in Fagus plicate, fatty). Germination phanerocotylar (in Fagus and Trigonobalanus s. lat.) or cryptocotylar.

Cytology x = (11, n = 22 in Trigonobalanus) 12 (13, 21) – Polyploidy rarely occurring.

DNA Plastid gene rpl22 transferred from plastid genome to nuclear genome (at least in Quercus present as pseudogene in plastid genome). Plastid gene rps16 absent (lost) in Fagus.

Phytochemistry Dihydroflavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), cyanidin, catechins, pentacyclic triterpenes, ellagic and gallic acids, hydrolyzable ellagi- and gallitannins, and condensed tannins (quercite, pentacid alcohol, in Quercus), and proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins) present. Alkaloids rare. Cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Ornamental plants, fruits (Castanea sativa), timber, carpentries, barrels, cork (Quercus suber), tanning (tannin from oak galls).

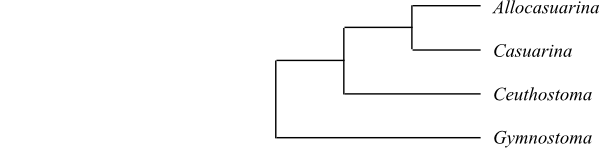

Systematics Fagaceae are sister-group to the remaining Fagales except Nothofagus.

Fagus is sister to all other Fagaceae.

Fagoideae K. Koch, Dendrologie 2(2): 16. Nov 1873 [’Fageae’]

1/10. Fagus (10; temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere). – Male inflorescence capitate. Pollen grains with finely scabrate exine. Stigma capitate. Micropyle bistomal, elongate. Inner integument thinner than outer. Nucellar cap approx. 13 cell layers thick. Cotyledons plicate. Germination phanerocotylar. Ellagic acid absent.

Quercoideae Irvine, London Fl.: 45. Sep-Dec 1838 [‘Quercineae’]

7–9/580–865. Trigonobalanus (1; T. verticillata; Indochina, Fraser’s Hill on the Malay Peninsula, Mt. Kinabalu on Borneo; incl. Colombobalanus? and Formanodendron?), Formanodendron (1; F. doichangensis; southern Yunnan, northern Thailand; in Trigonobalanus?), Colombobalanus (1; C. excelsa; Colombia; in Trigonobalanus?), Castanea (8; temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere, eastern Mediterranean to northern Iran), Castanopsis (c 120; tropical and subtropical regions in Asia, with their highest diversity on Borneo), Lithocarpus (100–335; India, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, Malesia), Chrysolepis (2; C. chrysophylla, C. sempervirens; western North America), Notholithocarpus (1; N. densiflorus; southwestern Oregon, California), Quercus (350–400; temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere south to mountains in Malesia and Colombia). – Temperate to tropical regions on the Northern Hemisphere. Inflorescence spicate or catkin-like. Exine with granular infratectum, scabrate, verrucate, verruculate, rugulate or smooth, anastomosingly striate. Stigmas capitate, decurrent, or punctate, with apical pore. Pistillodium sometimes nectar-secreting. Micropyle endostomal? Outer and inner integuments of approx. same length. Parietal tissue one cell layer thick. Nucellar cap approx. two cell layers thick. Cupule often cup-shaped, scaly. Fruit often rounded. Germination cryptocotylar or phanerocotylar.

|

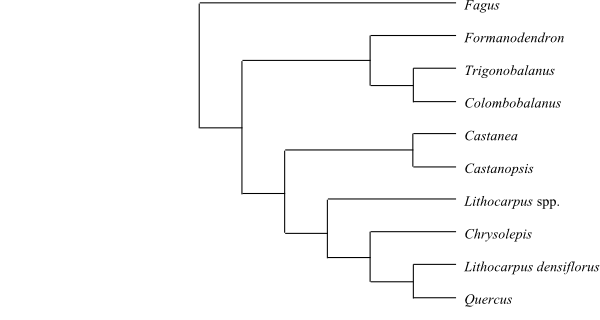

Cladogram of Fagaceae based on DNA sequence data (Manos & al. 2001). ‘Lithocarpus’ densiflorus has been transferred to the monospecific Notholithocarpus (as N. densiflorus). |

JUGLANDACEAE DC. ex Perleb |

( Back to Juglandales ) |

Engelhardtiaceae Reveal et Doweld in Novon 9: 552. 30 Dec 1999; Platycaryaceae Nakai ex Doweld in Byull. Mosk. Obshch. Ispyt. Prir., Biol. 105(5): 59. 9 Oct 2000

Genera/species 8/66

Distribution Southeast Europe to the Himalayas and Assam, East Asia to the Russian Far East and northern Vietnam, Taiwan, Southeast Asia to New Guinea, North America, the West Indies, Mexico to Colombia, the Andes, eastern Brazil.

Fossils Fossil wood, leaves, inflorescences, flowers, pollen grains and fruits of Juglandaceae are abundant in Cenozoic layers from the Paleocene onwards in the Northern Hemisphere. Fossil genera from the Palaeogene are, e.g., Alfaropsis, Casholdia, Cruciptera, Hooleya, Paleocarya, Paleooreomunnea, Paleoplatycarya, Paraengelhardia, Polyptera, and Sphaerocarya. Eocene fruit fossils, Alatonucula, similar to Juglandaceae, were found in Patagonia in Argentina (Hermsen & Gandolfo 2016).

Habit Usually monoecious (sometimes dioecious; in Platycarya occasionally bisexual), usually evergreen or deciduous trees (rarely shrubs). Sometimes aromatic. Buds covered by brown hairs, often scaly.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio superficial. Medulla usually entire (in species of Cyclocarya, Juglans and Pterocarya septated by diaphragms). Vessel elements with simple or scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, simple or bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids or fibre tracheids with simple or bordered pits, non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal scanty, aliform, confluent, vasicentric, scalariform, reticulate, unilateral, or banded (rarely absent). Tyloses abundant, thin-walled. Sieve tube plastids S type (without P-protein bodies). Nodes usually 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces (sometimes 5:5, pentalacunar with five traces). Secretory cells present or absent. Wood with chains of crystalliferous cells. Calciumoxalate as druses or prismatic or rhomboid crystals.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate or multiseriate, simple or branched, fasciculate, multiradiate, stellate, peltate or lepidote; glandular hairs often as resin-producing peltate glandular scales.

Leaves Usually alternate (spiral; in Oreomunnia and Alfaroa opposite), paripinnate or imparipinnate, leaflets entire, with conduplicate or involute ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection? Venation pinnate, semicraspedodromous or camptodromous. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Domatia as pockets or hair tufts, or absent. Mesophyll with idioblasts containing calciumoxalate as druses or single rhomboid crystals. Glands peltate, aromatic, with resin secretions and ethereal oils. Leaflet margins serrate or entire; leaf teeth cunonioid, with splayed, usually glandular apex, main vein of tooth being joined by branches leaving below or one branch proceeding above tooth.

Inflorescence Terminal or lateral, cymes in spicate or catkin-like synflorescence. Male and female inflorescences usually separate (in Platycarya bisexual paniculate inflorescences with central cone-like female inflorescence with male flowers at apex and surrounded by male inflorescences). Male inflorescences solitary or three to eight together; floral prophylls (bracteoles) two, adnate to receptacle (absent in Platycarya). Female inflorescences many-flowered and catkin-like, or two- to many-flowered and spicate; floral prophylls (bracteoles) usually two or three (absent in Alfaroa). Bracts entire or trilobate.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Epigyny. Tepals in male flowers one to five (absent in Carya; in Platycarya reduced), whorled, free; in female flowers four, whorled, connate (absent in Carya). Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens threeto more than 100, in one, antetepalous, or several whorls. Filaments filiform, short, free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse?, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually monoporate to 37-por(or)ate (in Platycarya with two pseudocolpi on each half), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with granular infratectum, spinulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of two (to four) connate carpels; median carpel adaxial. Ovary inferior, unilocular in upper part, incompletely septate in lower part; primary septum always present, secondary and tertiary septa sometimes present (ovary then bilocular, quadrilocular or octalocular at base). Styles single, simple, or stylodia two, free or slightly connate. Stigma bilobate to quadrilobate, usually with decurrent stigmatic surface, carinal (opposite centre of carpel) or commissural (opposite margins of two connate carpels; in Carya adnate to sepals and forming stigmatic disc), non-papillate, Dry type. Male flowers sometimes with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation modified axile (on top of incomplete primary septum) to basal. Ovule one per ovary (unilocular in upper part), orthotropous, ascending, unitegmic, crassinucellar. Integument six to ten cell layers thick. Parietal tissue three to eleven cell layers thick. Nucellar cap approx. two cell layers thick. Archespore multicellular. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Chalazogamy or porogamy. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis asterad.

Fruit A single-seeded nut, often with persistent bracts (in Pterocarya with two wings formed by floral prophylls; in Platycarya with two small processes each formed by one floral prophyll and one tepal; in Engelhardia and Oreomunnea with large trilobate wing formed by bract; in Cyclocarya with large circular wing formed by floral prophylls) or drupaceous (nut shell in Alfaroa formed by sepals; in Carya by involucral bract; in Juglans by involucral bract and sepals). Pericarp (endocarp) intrusive.

Seeds Seed pachychalazal, large, lobed. Aril absent. Testa? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm sparse or absent. Embryo large, well differentiated, oily, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, large, quadrilobate, strongly plicate, often fleshy, oily. Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = 14, 15, 16, 28, 32 (x = 16)

DNA Plastid gene rpl22 absent (lost).

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), flavones, cyanidin, delphinidin, ethereal oils, pentacyclic triterpenes, ellagic acid, galloyl tannins (especially in the bark), cyanogenic compounds, naphthoquinones, and citrullin present. Alkaloids not found. Aluminium accumulated in Carya and Engelhardia. Raffinose and stachyose present in phloem exudates

Use Ornamental plants, seeds and seed oils (Juglans, Carya), medicinal plants, timber, carpentries.

Systematics Juglandaceae are sister to Rhoiptelea (Rhoipteleaceae).

Engelhardioideae are sister-group to the remaining Juglandaceae.

Engelhardioideae Iljinsk. in Bot. Žurn. 75: 793. 11-30 Jun 1990

3/19. ’Engelhardia’ (8; E. apoensis, E. cathayensis, E. hainanensis, E. nudiflora, E. rigida, E. serrata, E. spicata, E. ursina; the Himalayas to China, Taiwan, Southeast Asia to New Guinea; paraphyletic), Oreomunnea (2; O. mexicana, O. pterocarpa; Mexico, Central America), Alfaroa (9; A. columbiana, A. costaricensis, A. guanacastensis, A. guatemalensis, A. hondurensis, A. manningii, A. mexicana, A. roxburghiana, A. williamsii; Mexico, Central America, Colombia). – Eastern Himalayas, China, Taiwan, Southeast Asia to New Guinea, Mexico to Colombia. Buds without bud scales. Foliar parenchyma with druses. Leaves sometimes opposite, pinnate, leaflets usually with entire margin. Bracts trilobate. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) one, two, adnate to lower part of ovary, or absent. Nut with layer of fibrous cells. – Platycarya has male and female flowers (sometimes bisexual flowers) in common spike-like inflorescence, strongly scented flowers, sticky pollen grains, cone-like infructescence, and bracts not forming parts of fruit.

Juglandoideae Eaton, Bot. Dict., ed. 4: 46. Apr-Mai 1836 [‘Juglandeae’]

5/47. Juglans (21; the Mediterranean through temperate Asia to Japan, southeastern Canada and the United States to the Andes in Argentina), Cyclocarya (1; C. paliurus; eastern China), Pterocarya (6; P. fraxinifolia: the Caucasus; P. hupehensis, P. macroptera, P. rhoifolia, P. stenoptera, P. tonkinensis: East and Southeast Asia), Carya (18; East Asia south to northern Vietnam, eastern North America to Central America), Platycarya (1; P. strobilacea; central and eastern China, the Korean Peninsula, Japan, northern Vietnam). – Southeast Europe, northern Turkey to the Himalayas, Assam, East Asia south to northern Vietnam and north to the Russian Far East, Central America, the West Indies, the Andes, eastern Brazil. Buds usually with bud scales. Vessel elements with simple perforation plates. Male flowers with unilobate bracts. Female flowers with entire bracts and floral prophylls (bracteoles) usually lateral and adnate to ovary. Pericarp with sclereids. Endocarp sometimes with lacunae. Outer part of fruit in Carya caducous.

|

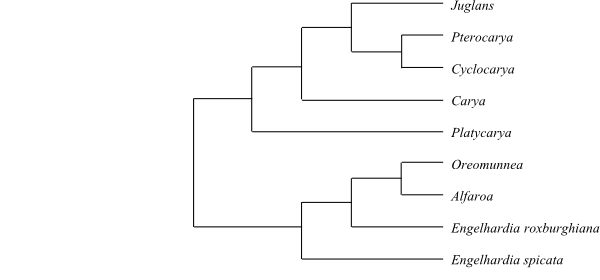

Cladogram of Juglandaceae based on DNA sequence data and morphology (Smith & Doyle 1995; Manos & Stone 2001). |

MYRICACEAE A. Rich. ex Kunth |

( Back to Juglandales ) |

Myricales A. Rich. in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp. Regn. Veg.: 12. Sep-Oct 1835 [’Myriceae’]; Canacomyricaceae Baum.-Bod. ex Doweld in Byull. Mosk. Obshch. Ispyt. Prir., Biol. 105(5): 59. 9 Oct 2000

Genera/species 4/c 50

Distribution Western and northern Europe, Macaronesia, tropical and southern Africa, Sri Lanka, the Himalayas, East Asia to Kamchatka and Japan, Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea, New Caledonia, North America, Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, the Andes south to Bolivia and Argentina.

Fossils Flowers, pollen grains and fruits of Myricaceae are known from the Santonian and the Cenomanian (Cretaceous) and abundant in Cenozoic strata. Fossil Comptonia and Myrica have been found in the Neogene of Europe and Asia. Fossil pollen grains of Canacomyrica have been described from Eocene to Miocene layers in New Zealand.

Habit Monoecious, andromonoecious or dioecious, evergreen or deciduous trees or shrubs. Usually aromatic.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza probably absent. Root nodules containing nitrogen fixing actinobacteria (Frankia) present in most Myricaceae (not found in Canacomyrica). Higher order rootlets clustered, with limited growth (proteoid roots). Phellogen ab initio superficial. Vessel elements with scalariform or simple perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, scalariform or opposite, bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements usually tracheids (in Myrica gale fibre tracheids) with simple or bordered pits, non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma usually apotracheal diffuse, diffuse-in-aggregates, or banded (rarely paratracheal scanty). Sieve tube plastids S type (without P-protein bodies). Nodes usually 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces (rarely 1:1, unilacunar with one trace). Wood with chains of crystalliferous cells. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals abundant.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate, simple, often vesicular; peltate-lepidote glandular hairs usually secreting waxy aromatic substances; sometimes also multicellular uniseriate hairs with oils.

Leaves Alternate (spiral), simple, usually entire (rarely pinnately lobed), with conduplicate to curved ptyxis. Stipules usually absent (in Comptonia laciniate and foliaceous); leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate. Venation pinnate, semicraspedodromous or camptodromous. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Epidermal cells with ethereal oils. Leaf margin serrate or irregularly dentate; leaf teeth cunonioid, with splayed, usually glandular apex, main vein of tooth being joined by branches leaving below or one branch proceeding above tooth.

Inflorescence Axillary, in Canacomyrica simple spicate, in Comptonia, Morella and Myrica branched spicate or catkin-like, or flowers solitary. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) in female flowers two to four, often accrescent and enclosing fruit, or absent.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. In Canacomyrica epigyny (in Comptonia hypogyny?). Tepals usually absent (in Canacomyrica six, very small, connate in lower part, gradually accrescent and enclosing fruit). Nectary absent. Disc annular, present in male flowers.

Androecium Stamens (one to) four to eight (to c. 20; in Canacomyrica six, antetepalous), in one whorl. Filaments usually free (sometimes connate), free from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, extrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory. Staminodia usually absent (female flowers in Canacomyrica with six epigynous staminodia).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tripor(or)ate (rarely tetraporate or di- or hexacolpate), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with granular infratectum, microperforate, coarsely scabrate (Canacomyrica), psilate or microechinate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of two (or three) connate carpels. Ovary inferior (in Canacomyrica), unilocular. Stylodia two (or three), free or connate at base. Stigmas capitate?, non-papillate, Dry type. Male flowers often with pistillodium (most significant in Canacomyrica).

Ovules Placentation basal. Ovule one per ovary, orthotropous, ascending, usually unitegmic (in Canacomyrica bitegmic, with curved and prolonged micropyle), crassinucellar. Integument three to seven cell layers thick, vascularized. Parietal tissue six to nine cell layers thick. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Pseudoporogamy (pollen tube growth temporarily ceasing on surface of megasporangium). Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis? Fertilization delayed.

Fruit Usually a drupe (in Comptonia a nutlet), often covered with outgrowths and sometimes fatty or waxy secretions, sometimes enclosed by floral prophylls (in Comptonia cupular; in Myrica gale modified into two buoyant structures).

Seeds Seed pachychalazal? Aril absent. Testa thickened. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm poorly developed or absent. Embryo straight, well differentiated, oily, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two, plano-convex. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology x = 8, 12 – Polyploidy frequently occurring (Myrica gale is a hexaploid in Europe and a dodecaploid in North America).

DNA

Phytochemistry Dihydroflavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), ethereal oils, resins, and balsam (with O- and C-methylated flavones; in glandular hairs and epidermal cells), cyanidin, delphinidin, pentacyclic triterpenes (of taraxerane, ursane and lupane type), ellagic acid, and hydrolyzable and condensed tannins present. Alkaloids and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Spices (Myrica gale), aromatic waxes, tanninic acid, medicinal plants.

Systematics Myrica (2; M. gale: western and northern Europe, northeastern Siberia, Canada, northern United States; M. hartwegii: Sierra Nevada in California), Comptonia (1; C. peregrina; eastern Canada, eastern United States), Morella (c 45; Macaronesia, tropical and southern Africa, Sri Lanka, the Himalayas, East Asia to Kamchatka and Japan, Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea, southern United States, Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, the Andes south to Bolivia and Argentina), Canacomyrica (1; C. monticola; New Caledonia).

Myricaceae are sister to [Rhoiptelea+Juglandaceae].

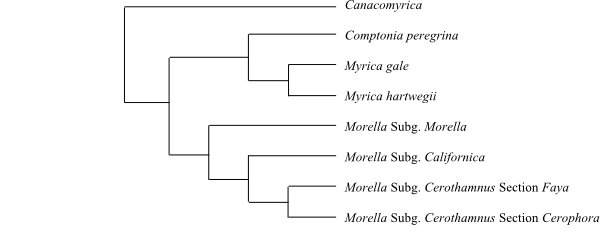

Canacomyrica is sister to the remaining Myricaceae, a probable topology being [Canacomyrica+[Morella+[Myrica+Comptonia]]].

The [Comptonia+Myrica] clade is nodulated by the Alnus-infective Frankia strains, whereas the Morella clade is nodulated by the Elaeagnaceae-infective Frankia strains (Huguet & al. 2005).

|

Cladogram of Myricaceae based on DNA sequence data (Huguet & al. 2005; Herbert & al. 2006). |

NOTHOFAGACEAE Kuprian. |

( Back to Juglandales ) |

Nothofagales Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.: xl. 23 Dec 2001

Genera/species 1/37–38

Distribution New Guinea, the D’Entrecasteaux Islands (Goodenough, Normandie), New Britain, eastern and southeastern Australia, Tasmania, New Caledonia, New Zealand, southern South America (including Staten Island) south of 33ºS.

Fossils Nothofagus, mainly pollen grains, has been recorded in Antarctica and subantarctic areas, in southern South America, Australia, New Zealand and Melanesia in strata from the Maastrichtian onwards, and pollen grains of the fossil Nothofagidites, are known from the Early Campanian of South Australia. Nothofagoxylon, wood of probable nothofagaceous origin, has been found in Antarctica.

Habit Monoecious, evergreen or deciduous trees or shrubs. Horizontal lenticels often abundant. Bud scales decussate.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio superficial. Vessel elements with simple or scalariform (sometimes reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform, opposite or alternate, simple pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform fibres with simple pits, septate or non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or somewhat heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or narrowly banded, or absent. Wood elements partially storied. Tyloses abundant. Sieve tube plastids S type, with non-dispersive P-protein bodies. Nodes usually 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces (in Nothofagus obliqua probably unilacunar). Heartwood with resinous substances? Sclereid nests? Silica bodies present in some species. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals often frequent.

Trichomes Hairs multicellular, simple, branched or stellate?; glandular hairs peltate-lepidote.

Leaves Alternate (usually distichous, sometimes spiral), simple, entire, often with plicate ptyxis. Stipules usually peltate, caducous, at base surrounding narrowly elongate colleters; leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection? Venation pinnate. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Domatia? Epidermis with or without mucilage cells? Leaf margin serrate (often biserrate) or entire; leaf teeth compound. Glands large, multicellular (rarely absent).

Inflorescence Axillary, cymose catkin-like, usually composed of one- to three-flowered dichasia; each female inflorescence usually surrounded by (bilobate to) quadrilobate cupule, shoot consisting of sterile inflorescence parts, scaly on abaxial side (cupule in some species of Nothofagus as two small lobes or absent). Flowers with numerous stamens interpreted as pseudanthia, formed as connate dichasia.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Epigyny. Tepals in male flowers four to seven, with imbricate aestivation, scale-like, in one whorl, connate; tepals absent in female flowers. Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens eight to c. 40. Filaments filiform, free from each other and from tepals; point of connection to anther markedly narrowed. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, extrorse?, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective usually prolonged. Tapetum secretory. Female flowers sometimes with staminodia.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains shortly (3–)6–7(–10)-stephanocolpate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with granular acolumellate infratectum, loosely spinulate or verrucate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of two or three connate carpels; median carpel abaxial; terminal flower often with two carpels, lateral flowers often with three carpels. Ovary inferior, bilocular or trilocular. Style single, simple, sometimes short. Stigma lobate, lobes decurrent, non-papillate, Dry type. Male flowers with or without pistillodium?

Ovules Placentation apical to axile. Ovules two per carpel, anatropous, pendulous, unitegmic, crassinucellar. Integument four to seven cell layers thick. Suprachalazal tissue massive. Parietal tissue probably one or two cell layers thick. Nucellar cap absent. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type, with lateral caecum at base? Porogamy or chalazogamy? Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis onagrad?

Fruit A nutlet, calybium, sometimes winged; (one to) three (to seven) fruits surrounded by bivalvular to quadrivalvular usually lamellate cupule. Pericarp partially sclereidal. Endocarp glabrous inside.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm absent. Embryo large, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, plicate, oily. Germination phanerocotylar?

Cytology n = 13

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin?), flavanones, flavanonols, catechin, ellagic acid, tannins, proanthocyanidins, and stilbenes present. Alkaloids? Cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Ornamental plants, timber, carpentries.

Systematics Nothofagus (37–38; New Guinea, the D’Entrecasteaux Islands of Goodenough and Normandie, New Britain, New Caledonia, eastern Queensland, eastern New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, New Zealand, temperate Chile and Argentina).

Nothofagaceae are sister-group to the remaining Juglandales.

RHOIPTELEACEAE Hand.-Mazz. |

( Back to Juglandales ) |

Rhoipteleales Novák ex Reveal in Novon 2: 239. 13 Oct 1992

Genera/species 1/1

Distribution Southwestern China to northern Vietnam.

Fossils Campanian to Maastrichtian fossil fruits assigned to Rhoiptelea pontwallensis are known from Central Europe. Pollen grains resembling those in Rhoiptelea have been found in the Maastrichtian of eastern North America, and possibly in Late Cretaceous and Paleocene layers in Europe. Pollen grains, Plicapollis, which are associated with the Late Cretaceous Budvaricarpus and Caryanthus flowers, are similar to the Rhoiptelea pollen. Budvaricarpus and Caryanthus resemble to some degree Rhoiptelea flowers in, e.g., the quadritepalous perianth, the hexamerous androecium and the bicarpellate uniovular gynoecium.

Habit Bisexual or gynomonoecious, deciduous trees. Aromatic. Lenticels abundant. Bud scales absent.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen? Wood diffusely porose (pits usually solitary). Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids with simple pits, non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal vasicentric or banded. Tyloses abundant. Sieve tube plastids S type (without P-protein bodies?). Nodes 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces. Wood with chains of crystalliferous cells? Crystals?

Trichomes Hairs multicellular, uniseriate, simple, brown; glandular hairs aromatic, peltate or cupular, resinous.

Leaves Alternate (distichous), imparipinnate, with ? ptyxis. Stipules asymmetrically caudate, thin, caducous; leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection? Venation pinnate. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Leaflet margins serrate; leaf teeth with splayed, usually glandular apex, main vein of tooth being joined by branches leaving below or one branch proceeding above tooth.

Inflorescence Axillary, horsetail-like branched panicle with six to eight catkin-like branches. Partial inflorescences composed of dichasia, with one bisexual terminal flower and female or sterile lateral flowers.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Hypogyny (probably secondarily). Tepals in bisexual flowers 2+2, persistent in fruit. Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens six. Filaments short, free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse?, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory? Staminodia?

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous? Pollen grains tricolporate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate to granular infratectum, scabrate, microperforate; exine plicate, without vestibulum between ectexine and endexine.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of two connate carpels; adaxial carpel usually sterile and degenerated. Ovary superior (probably secondarily), bilocular in lower part, unilocular in upper part. Stylodia two, free. Stigmas two, flattened, commissural, recurved, type? Pistillodium?

Ovules Placentation modified axile (on top of incomplete primary septum in one locule). Ovule one per ovary, campylotropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle ?-stomal. Outer integument ? cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Chalazogamy or porogamy? Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A one-seeded samaroid nut with persistent perianth. Exocarp covered with brown glands and provided with two wing-like processes.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa hard. Tegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm absent. Embryo straight, oily, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two, thick. Germination?

Cytology n = 16

DNA

Phytochemistry Very insufficiently known. Tannins present (especially in bark).

Use Timber.

Systematics Rhoiptelea (1; R. chiliantha; southwestern China to northern Vietnam).

Rhoiptelea is sister to Juglandaceae.

TICODENDRACEAE Gómez-Laur. et L. D. Gómez |

( Back to Juglandales ) |

Genera/species 1/1

Distribution Mountains in southern Mexico and Central America.

Fossils Fossilized fruits, Ferrignocarpus bivalvis, and pollen grains possibly assignable to Ticodendron, have been found in Eocene layers in Oregon and in the Early Eocene London Clay in England.

Habit Dioecious or polygamodioecious, evergreen tree. Bud scales?

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen? Vessel elements with scalariform or reticulate perforation plates; lateral pits usually scalariform (sometimes opposite or intermediate), simple or bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids with bordered pits, non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates. Secondary phloem not stratified. Sieve tube plastids S type (sieve tubes with non-dispersive P-protein bodies?). Nodes probably 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals abundant. Bark cells with sclereids and rhomboidal crystals.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular, T-shaped; glandular hairs absent.

Leaves Alternate (spiral), simple, entire, coriaceous, with ? ptyxis. Stipules narrowly elongate, intrapetiolar, sheathing, caducous; leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection? Venation pinnate, craspedodromous; almost all leaf teeth directly vascularized by secondary veins. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Idioblasts (sometimes with druses) present in hypodermis and below midvein. Mesophyll cells with druses of aberrant type. Epidermis with mucilage cells? Leaf margin biserrate; secondary veins proceeding directly into leaf teeth.

Inflorescence Male flowers in terminal or axillary spicate or catkin-like inflorescences, simple or branched (sometimes with terminal female flower), consisting of verticillate dichasia with one to three flowers; each dichasium subtended by one bract. Female flowers solitary (reduced cymes); each female flower surrounded by one bract and subtended by two floral prophylls (bracteoles); floral prophylls of female flowers with axillary groups of vascularized scales.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Epigyny. Male flowers without tepals; tepals of female flowers very small and reduced, connate. Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens eight or ten or more, in two to four whorls surrounded by three caducous bracts. Filaments filiform, free. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, extrorse?, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective prolonged at apex. Tapetum secretory. Staminodia usually absent (sometimes present in female flowers).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous? Pollen grains tripor(or)ate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate to granular infratectum, microperforate, spinulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of two (or three) connate (tangentially orientated?) carpels. Ovary inferior, quadrilocular, with septate locules. Stylodia two (or three), entirely covered by stigmatic areas. Stigmas long, non-papillate, Dry type? Pistillodium usually absent (rarely present in male flowers).

Ovules Placentation apical-axile. Ovule one per carpel, hemitropous, pendulous, unitegmic, crassinucellar. Integument c. 20 to c. 30 cell layers thick, vascularized. Parietal tissue approx. six cell layers thick. Nucellar cap absent. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Chalazogamy. Endosperm development nuclear? Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis? Fertilization delayed.

Fruit A single-seeded drupe.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa vascularized. Exotestal cells ab initio radially elongate, all cells thick-walled and tanniniferous. Endotesta? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm thin, two-layered. Embryo large, straight, well differentiated, oily, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Germination cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = 13

DNA

Phytochemistry Very insufficiently known. Dihydroflavonols (myricetin) and tannins present. Pentacyclic triterpenes? Ellagic acid?

Use Unknown.

Systematics Ticodendron (1; T. incognitum; southern and southeastern Mexico, Central America, especially eastern mountain slopes in eastern Mexico to central Panamá).

Ticodendron is sister to Betulaceae.

Literature

Abbe EC. 1935. Studies in the phylogeny of the Betulaceae I. Floral and inflorescence anatomy and morphology. – Bot. Gaz. 97: 1-67.

Abbe EC. 1938. Studies in the phylogeny of the Betulaceae II. Extremes in the range of variation of floral and inflorescence morphology. – Bot. Gaz. 99: 431-469.

Abbe EC. 1963. The male flowers and inflorescence of the Myricaceae. – Amer. J. Bot. 50: 632.

Abbe EC. 1972. The inflorescence and flower in male Myrica esculenta var. farquhariana. – Bot. Gaz. 133: 206-213.

Abbe EC. 1974. Flowers and inflorescences of the Amentiferae. – Bot. Rev. 40: 159-261.

Abbe LB, Abbe EC. 1971. The vessel member of Myrica esculenta Buch. Ham. – J. Minnesota Acad. Sci. 37: 72-76.

Acosta MC, Premoli AC. 2010. Evidence of chloroplast capture in South American Nothofagus (subgenus Nothofagus, Nothofagaceae). – Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 54: 235-242.

Akkermans ADL, Roelofsen W, Blom J, Huss-Danell K, Harkink R. 1983. Utilization of carbon and nitrogen compounds by Frankia in synthetic media and in root nodules of Alnus glutinosa, Hippophae rhamnoides, and Datisca cannabina. – Can. J. Bot. 61: 2793-2800.

Akkermans ADL, Hafeez F, Roelofsen W, Chaudhary AH, Baas R. 1983. Ultrastructure and nitrogenase activity of Frankia grown in pure culture and in actinorrhizae of Alnus, Colletia and Datisca. – In: Veeger C, Newton WE (eds), Advances in nitrogen fixation research, Nijhoff/Dr. W. Junk, The Hague, The Netherlands, pp. 311-319.

Aradhya MK, Potter D, Gao F, Simon CJ. 2007. Molecular phylogeny of Juglans (Juglandaceae): a biogeographic perspective. – Tree Gen. Genomes 3 363-378.

Axelrod DI. 1983. Biogeography of oaks in the Arcto-Tertiary province. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 70: 629-657.

Baas P. 1982. Comparative leaf anatomy of Trigonobalanus Forman (Fagaceae). – Blumea 28: 171-175.

Backer CA. 1951. Myricaceae. – In: Steenis CGGJ van (ed), Flora Malesiana I, 4(3), Noordhoff-Kolff N. V., Batavia, pp. 276-279.

Baird JR. 1969. A taxonomic revision of the plant family Myricaceae of North America, North of Mexico. – Ph.D. diss., University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Barlow BA. 1958. Heteroploid twins and apomixis in Casuarina nana Sieb. – Aust. J. Bot. 6: 204-219.

Barlow BA. 1959a. Chromosome numbers in the Casuarinaceae. – Aust. J. Bot. 7: 230-237.

Barlow BA. 1959b. Polyploidy and apomixis in the Casuarina distyla species group. – Aust. J. Bot. 7: 238-251.

Barlow BA. 1983. Casuarina – a taxonomic and biogeographic review. – In: Midgley SJ, Turnbull JW, Johnston RD (eds), Casuarina ecology, management and utilization, CSIRO, Melbourne, Victoria, pp. 10-18.

Barnett EC. 1944. Keys to the species groups of Quercus, Lithocarpus and Castanopsis of eastern Asia with notes on their distribution. – Trans. Bot. Soc. Edinb. 34: 159-204.

Baumann-Bodenheim MG. 1953. Fagacées de la Nouvelle Calédonie. – Bull. Mus. Natl. Hist. Nat., sér. II, 25: 419-421.

Baumann-Bodenheim MG. 1992. Trisyngyne. Systematik der Flora von Neu-Caledonien (Melanesien-Südpazifik). – Mrs A. L. Baumann, Herrliberg.

Belahbib N, Pemonge M-H, Ouassu A, Sbay H, Kremer A, Petit RJ. 2001. Frequent cytoplasmic exchange between oak species that are not closely related: Quercus suber and Q. ilex in Morocco. – Mol. Ecol. 10: 2003-2012.

Behnke H-D. 1991. Sieve-element characters of Ticodendron. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 78: 131-134.

Bellarosa R, Delre V, Schirone B, Maggini F. 1990. Ribosomal RNA genes in Quercus spp. (Fagaceae). – Plant Syst. Evol. 172: 127-139.

Benoît LF, Berry AM. 1997. Flavonoid-like compounds from seeds of red alder (Alnus rubra) influence host nodulation by Frankia (Actinomycetales). – Physiol. Plant. 99: 588-593.

Bergero R, Perotto S, Girlanda M, Vidano G, Luppi AM. 2000. Ericoid mycorrhizal fungi are common root associates of a Mediterranean ectomycorrhizal plant (Quercus ilex). – Mol. Ecol. 9: 1639-1649.

Berquam DL. 1975. Floral morphology and anatomy of staminate Juglandaceae. – Ph.D. diss., University of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota.

Berridge EM. 1914. The structure of the flower of the Fagaceae and its bearing on the affinities of the group. – Ann. Bot. 28: 509-526.

Berry AM, McIntyre L, McCully ME. 1986. Fine structure of root hair infection leading to nodulation in the Frankia-Alnus symbiosis. – Can. J. Bot. 64: 292-305.

Blokhina NI. 2004. On some aspects of systematics and evolution of the Engelhardioideae (Juglandaceae) by wood anatomy. – Acta Palaeont. Rom. 4: 13-21.

Bloom RA, Mullin BC, Tate L III. 1989. DNA restriction patterns and DNA-DNA solution hybridization studies of Frankia isolates from Myrica pensylvanica (Bayberry). – Appl. Environm. Microbiol. 55: 2155-2160.

Bloom RA, Lechevalier MP, Tate RL. 1989. Physiological, chemical, morphological, and plant infectivity characteristics of Frankia isolates from Myrica pensylvanica: correlation to DNA restriction patterns. – Appl. Environm. Microbiol. 5: 2161-2166.

Bond G. 1951. The fixation of nitrogen associated with the root nodules of Myrica Gale L., with special reference to its pH relation and ecological significance. – Ann. Bot., N. S., 15: 447-459.

Bond G. 1952. Some features of root growth in nodulated plants of Myrica gale L. – Ann. Bot., N. S., 16: 467-475.

Boodle LA, Worsdell WC. 1894. On the comparative anatomy of the Casuarinaceae, with special reference to the Gnetaceae and Cupuliferae. – Ann. Bot. 8: 231-264.

Bordács S, Popescu F, Slade D, Csaikl UM, Lesur I, Borovcs A, Kézdy P, König AO, Gömoröy D, Brewer S, Burg K, Petit RJ. 2002. Chloroplast DNA variation of white oaks in northern Balkans and in the Carpathian Basin. – For. Ecol. Manag. 156: 197-209.

Bos JAA, Punt W. 1991. Juglandaceae. – Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 69: 79-95.

Bousquet J, Lalonde M. 1990. The genetics of actinorhizal Betulaceae. – In: Schwintzer CR, Tjepkema JD (eds), The biology of Frankia and actinorhizal plants, Academic Press, Orlando, pp. 239-261.

Bousquet J, Cheliak WM, Lalonde M. 1987a. Genetic differentiation among 22 mature populations of green alder (Alnus crispa) in central Québec. – Can. J. For. Res. 17: 219-227.

Bousquet J, Cheliak WM, Lalonde M. 1987b. Allozyme variability in natural populations of green alder (Alnus crispa). – Genome 29: 345-352.

Bousquet J, Cheliak WM, Lalonde M. 1987c. Genetic diversity within and among 11 juvenile populations of green alder (Alnus crispa) in Canada. – Physiol. Plant. 70: 311-318.

Bousquet J, Cheliak WM, Lalonde M. 1988. Allozyme variation within and among mature populations of speckled alder (Alnus rugosa) and relationships with green alder (A. crispa). – Amer. J. Bot. 75: 1678-1686.

Bousquet J, Girouard E, Strobeck C, Dancik BP, Lalonde M. 1989. Restriction fragment polymorphisms in the rDNA region among seven species of Alnus and Betula papyrifera. – Plant and Soil 118: 231-240.

Bousquet J, Cheliak MW, Yang J, Lalonde M. 1990. Genetic divergence and introgressive hybridization between Alnus sinuata and A. crispa (Betulaceae). – Plant Syst. Evol. 170: 107-124.

Bousquet J, Strauss SH, Li P. 1992. Complete congruence between morphological and rbcL-based molecular phylogenies in birches and related species (Betulaceae). – Mol. Biol. Evol. 9: 1076-1088.

Brett DW. 1964. The inflorescence of Fagus and Castanea and the evolution of the cupules of the Fagaceae. – New Phytol. 63: 96-118.

Brown RW. 1946. Walnuts from the Late Tertiary of Ecuador. – Amer. J. Sci. 243: 554-556.

Brunner F, Fairbrothers DE. 1979. Serological investigation of the Corylaceae. – Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 106: 97-103.

Burger WC. 1975. The species concept in Quercus. – Taxon 24: 45-50.

Callaham D, Newcomb W, Torrey JG, Peterson RL. 1979. Root hair infection in actinomycete-induced root nodule initiation in Casuarina, Myrica, and Comptonia. – Bot. Gaz. (Suppl.) 140: S1-S9.

Campbell JD. 1985. Casuarinaceae, Fagaceae, and other plant megafossils from Kaikorai Leaf Beds (Miocene) Kaikorai Valley, Dunedin, New Zealand. – New Zealand J. Bot. 23: 311-320.

Campbell JD, Holden AM. 1984. Miocene casuarinacean fossils from Southland and Central Otago, New Zealand. – New Zealand J. Bot. 22: 159-167.

Camus A. 1929. Les chataigniers: monographie des Castanea et Castanopsis. – In: Encyclopédie économique de sylviculture 3, Académie des Sciences, Paris.

Camus A. 1936-1954. Les chênes. Monographie du genre Quercus et du genre Lithocarpus. – In: Encyclopédie économique de sylviculture 6-8, Académie de Sciences, Lechevalier, Paris.

Cannon CH, Manos PS. 2000. The Bornean Lithocarpus Bl. section Synaedrys (Lindley) Barnett (Fagaceae): discussion of its circumscription and description of a new species. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 133: 343-357.

Cannon CH, Manos PS. 2001. Combining and comparing morphometric shape descriptors with a molecular phylogeny: the case of fruit type evolution in Bornean Lithocarpus (Fagaceae). – Syst. Biol. 50: 860-880.

Cannon CH, Manos PS. 2003. Phylogeography of the Southeast Asian stone oaks (Lithocarpus). – J. Biogeogr. 30: 211-226.

Carlquist SJ. 1987. Pliocene Nothofagus wood from the Transantarctic Mountains. – Aliso 11: 571-583.

Carlquist SJ. 1991. Wood and bark anatomy of Ticodendron: comments on relationships. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 78: 96-104.

Carlquist SJ. 2002 [2004]. Wood and bark anatomy of Myricaceae: relationships, generic definitions, and ecological interpretations. – Aliso 21: 7-29.

Carpenter RJ, Bannister JM, Lee DE, Jordan

GJ. 2014. Nothofagus subgenus Brassospora (Nothofagaceae) leaf fossils from

New Zealand: a link to Australia and New Guinea? – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 174:

503-515.

Chanda S. 1969. A contribution to the palynotaxonomy of Casuarinaceae. – J. Sen Mem. Vol., Bot. Soc. Bengal, Calcutta, pp. 191-208.

Chang C-Y. 1981. Morphology of the family Rhoipteleaceae in relation to its systematic position. – Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 19: 168-178. [In Chinese with English summary]

Chen G, Sun W-B, Han C-Y, Coombes A. 2007. Karyomorphology of the endangered Trigonobalanus doichangensis (A. Camus) Forman (Fagaceae) and its taxonomic and biogeographical implications. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 154: 321-330.

Chen Y, Manchester SR, Song Z, Wang H. 2014. Oligocene fossil winged fruits of tribe Engelhardieae (Juglandaceae) from the Ningming Basin of Guangxi Province, south China. – Intern. J. Latest Res. Sci. Technol. 3: 13-17.

Chen Z-D. 1991. Pollen morphology of the Betulaceae. – Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 29: 464-475. [In Chinese with English summary]

Chen Z-D. 1994. Phylogeny and phytogeography of the Betulaceae. – Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 32: 1-32, 101-153. [In Chinese with English summary]

Chen Z-D, Li J-H. 2004. Phylogenetics and biogeography of Alnus (Betulaceae) inferred from sequences of nuclear ribosomal DNA ITS region. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 165: 325-335.

Chen Z-D, Zhang Z-Y. 1991. A study on foliar epidermis in the Betulaceae. – Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 29: 156-165. [In Chinese with English summary]

Chen Z-D, Lu A-M, Pan K-Y.1990. The embryology of the genus Ostryopsis (Betulaceae). – Cathaya 2: 53-62.

Chen Z-D, Wang X-Q, Sun H-Y, Han Y, Zhang Z-X, Zou Y-P, Lu A-M. 1998. Systematic position of the Rhoipteleaceae: evidence from nucleotide sequences of rbcL gene. – Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 36: 1-7.

Chen Z-D, Manchester SR, Sun H-Y. 1999. Phylogeny and evolution of the Betulaceae as inferred from DNA sequences, morphology, and paleobotany. – Amer. J. Bot. 86: 1168-1181.

Chevalier A. 1901. Monographie des Myricacées: anatomie et histologie, organographies, classification et description des espèces, distribution géographique. – Mém. Soc. Sci. Nat. Cherbourg 32: 85-340.

Chevalier A. 1941. Variabilité et hybridité chez les noyers. Notes sur des Juglans peu connus, sur l’Annamocarya et un Carya d’Indochine. – Rev. Bot. Appl. Agric. Trop. 21: 477-509.

Chourey MS. 1974. A study of the Myricaceae from Eocene sediments of southeastern North America. – Palaeontographica, B 146: 88-153.

Christophel DC. 1980. Occurrence of Casuarina megafossils in the Tertiary of south-eastern Australia. – Aust. J. Bot. 28: 249-259.

Christopher RA. 1979. Normapolles and triporate pollen assemblages from the Raritan and Magothy Formations (Upper Cretaceous) of New Jersey. – Palynology 3: 73-121.