CARYOPHYLLIDAE Takht.

Takhtajan, Sist Filog. Cvetk. Rast. [Syst.

Phylog. Magnolioph.]: 144. 4 Feb 1967

[Berberidopsidales+Caryophyllales]

CARYOPHYLLALES Juss. ex Bercht.

et J. Presl

Berchtold et Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 239. Jan-Apr

1820 [‘Caryophyllaceae’]

Caryophyllanae

Takht., Sist. Filog. Cvetk. Rast. [Syst. Phylog. Magnolioph.]: 144. 4 Feb

1967

Fossils There are relatively

few unambiguous fossils of Caryophyllales. Fossil

flowers (e.g. Caryophylloflora paleogenica) with pantoporate pollen

grains and campylotropous ovules, but with segmented ovary, have been found in

Late Cretaceous (Turonian) and Eocene layers.

Habit Usually bisexual

(sometimes monoecious, andromonoecious, gynomonoecious, polygamomonoecious,

dioecious, androdioecious, or gynodioecious), usually perennial, biennial or

annual herbs (sometimes evergreen or deciduous trees, shrubs, suffrutices or

lianas). Often leaf or stem succulents. Often halophytes. Often with spines.

C4 or CAM (crassulacean acid metabolism) physiologies often present

as well as Kranz’ anatomy. Often mucilaginous. Sometimes carnivorous.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza

absent in most groups (present in, i.a., Amaranthaceae and Nyctaginaceae). Root hair

cells arranged in vertical rows. Phellogen epidermal, subepidermal,

outer-cortical or pericyclic, or absent. Stem cortex often with two zones,

outer with thick-walled fibrous cells, inner with thin-walled cells. Secondary

lateral growth normal or anomalous (from concentric/successive cambia or from

inner whorl of vascular bundles), or absent. Vessel elements with simple

perforation plates; lateral pits usually alternate (sometimes opposite or

pseudoscalariform), usually simple (sometimes bordered) pits. Imperforate

tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids or libriform fibres (sometimes

tracheids) with usually simple (sometimes bordered) pits, septate or

non-septate (sometimes also vasicentric tracheids). Vestured pits sometimes

present. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular,

or absent. Axial parenchyma apotracheal, diffuse (sometimes

diffuse-in-aggregates), or paratracheal, scanty vasicentric, aliform,

winged-aliform, confluent, unilateral, or banded, or absent. Intraxylary phloem

rarely present. Sieve tube plastids S0, Ss, Pcs, P3c, P3cf, P3c’f,

P3f, P3c’’f, P3cfs, or P3c’’fs type. Nodes usually 1:1, 1:3 or 3:3,

unilacunar or with one or three leaf traces, or trilacunar with three traces

(sometimes 5–9:5–9, multilacunar with five to nine traces). Parenchyma

often with mucilaginous cells, often with sclereids. Wood with idioblasts

containing sphaerites. Tanniniferous cells sometimes present. Silica bodies

sometimes present in parenchyma cells. Calciumoxalate often present as druses,

sphaerites, styloids, raphides, prismatic or acicular crystals, or crystal

sand.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or

multicellular, uniseriate or multiseriate, simple or branched (two-branched,

T-shaped, dendritic, candelabra-shaped, stellate, fasciculate, lepidote,

rosulate, barbed or vesicular), or absent; glandular hairs often frequent,

multicellular, stalked or sessile (occasionally peltate-lepidote; sometimes

secreting viscous mucilage).

Leaves Alternate (usually

spiral, rarely distichous) or opposite (rarely verticillate), simple, usually

entire (rarely lobed), often succulent, with conduplicate, supervolute, flat,

involute or circinate ptyxis (sometimes scale-like or absent). Stipules usually

absent (sometimes intrapetiolar); leaf sheath usually absent (leaf bases

sometimes sheathingly connate). Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate or

annular, with peripheral ring of fibres. Venation pinnate or palmate,

brochidodromous or parallelodromous (sometimes indistinct; leaves sometimes

one-veined). Stomata usually paracytic, diacytic or anomocytic (sometimes

anisocytic, cyclocytic, tetracytic or actinocytic, rarely brachyparacytic).

Cuticular wax crystalloids as rodlets, threads or platelets, or absent. Leaf

margin usually entire (rarely dentate, sinuate, serrate or glandular-serrate).

Salt-secreting glands sometimes present.

Inflorescence Terminal or

axillary, cymose combinations of dichasia and cincinni, thyrsoid, fasciculate,

panicle, raceme-, spike- or head-like (flowers sometimes single). Floral

prophylls (bracteoles) sometimes numerous, sometimes absent.

Flowers Usually actinomorphic

(rarely zygomorphic). Hypanthium sometimes present. Usually hypogyny (rarely

half epigyny). Sepals (one to) five (to 23), usually with imbricate (sometimes

valvate, induplicate-valvate or open, rarely valvate-decussate, plicate or

descending-cochlear) aestivation, free or more or less connate. Petals alt.

petaloid staminodia (four or) five, with contorted or imbricate aestivation,

free, or absent. Nectaries/nectariferous disc present at staminal bases or in

tube formed by filament bases and petal bases or on inner side of receptacle,

or nectary and disc absent.

Androecium Stamens (one to)

five to more than 4.000 (staminal primordia usually five), in one or more

whorls or in several groups (outer stamens often initiated in pairs),

antetepalous when stamens isomerous relative to tepals; staminal development

usually centrifugal. Filaments free or more or less connate, sometimes adnate

to sepals or petals. Anthers basifixed or dorsifixed (sometimes latrorse),

versatile or non-versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (rarely disporangiate),

usually introrse (sometimes extrorse), usually longicidal (dehiscing by

longitudinal slits; rarely poricidal, dehiscing by apical pores or pore-like

slits); outer parietal cells developing directly into endothecium. Tapetum

usually secretory (rarely amoeboid-periplasmodial). Female flowers often with

staminodia (staminodia sometimes numerous in bisexual flowers). ‘Petaloids’

possibly in reality petaloid staminodia, developing simultaneously as or after

androecium (not prior to); petaloid staminodia (’petals’) and

’antepetalous’ stamens possibly forming a developmental unit.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tricolpate (rarely di- or

tricolporate, or di- or tricolporoidate) or tetra-, hexa- or polypantoporate

(sometimes tri- or hexarugate, rarely 4–12-colpate, spiraperturate,

triporate, etc.), shed as monads, usually tricellular rarely bicellular) at

dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate (rarely intectate), with columellate

infratectum, perforate, microperforate, punctate, punctitegillate or

reticulate, scabrate, or spinulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

(one or) two to five (to numerous) free or connate carpels; closure of carpels

sometimes delayed in at least Polygonaceae and in “the

betalain clade” (Caryophyllales s.str.).

Ovary superior, semi-inferior or inferior, unilocular to multilocular; ovary

sometimes with subepidermal cell layer containing large amounts of

calciumoxalate. Stylodia two to five, free or more or less connate, or style

single, simple; style sometimes unifacial. Stigmas two to five, or stigma one,

capitate or lobate, papillate, Dry type. Pistillodium usually absent (male

flowers often with pistillodium).

Ovules Placentation axile,

basal, basal-parietal, basal-lateral or free central (sometimes

parietal-laminar, rarely apical or basal-laminar). Ovules one to numerous per

carpel, campylotropous, hemianatropous or anacampylotropous (rarely anatropous,

circinotropous or amphitropous), ascending, erect, horizontal or pendulous,

apotropous or epitropous, usually bitegmic (rarely unitegmic), crassinucellar

(rarely tenuinucellar). Placental or funicular obturator sometimes present.

Micropyle usually endostomal (rarely bistomal). Funicle often with short hairs

directed against micropyle. Megasporangium usually thin. Archespore unicellular

to tricellular, only one developing further. Nucellar cap or nucellar beak

often present. Apical cells of megasporangium often radially elongate, forming

nucellar pad. Megagametophyte usually monosporous, Polygonum type

(rarely disporous or tetrasporous, Allium,

Adoxa,Endymion, Penaea, Drusa,

Fritillaria, Chrysanthemum, Plumbago, or

Plumbagella type). Synergids sometimes with a filiform apparatus.

Antipodal cells three, ephemeral, sometimes with early degenerating nuclei.

Chalazal caecum developed. Endosperm development ab initio usually nuclear

(sometimes cellular). Endosperm haustoria chalazal or absent. Embryogenesis

caryophyllad, chenopodiad or solanad (sometimes onagrad or asterad).

Fruit Usually a loculicidal

and/or septicidal (rarely denticidal, circumscissile or valvate) capsule

(sometimes a nut or an irregularly dehiscing capsule; rarely a berry, a

berry-like fruit, a drupe, a schizocarp or a syncarp), sometimes with

persistent calyx. Bracts and floral prophylls often partitioning in formation

of dispersal unit.

Seeds Aril usually absent.

Seed coat usually exotestal and/or endotegmic. Exotesta often tanniniferous;

outer exotestal wall sometimes with stalactite-like processes. Endotesta

sometimes thickened, often crystalliferous. Exotegmen? Endotegmen sometimes

with rod-shaped thickenings in cell walls, often tanniniferous. Perisperm

copious, starchy (with starch grains), surrounded by embryo, or not developed.

Endosperm copious, sparse or absent. Embryo usually lateral-peripheral, curved

around perisperm or straight (rarely cochleate or annular), with or without

chlorophyll. Cotyledons usually two (rarely one or three). Germination

phanerocotylar.

Cytology x = (4–)5–19

DNA Three large deletions

present in plastid ORF2280. Intron absent from plastid gene rpl2. The

plastid gene rpl23 is a pseudogene at least in the Caryophyllales analysed.

I copy of nuclear gene RPB2 lost. Mitochondrial intron

coxII.i3 sometimes lost.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), flavonol sulphates,

flavone-C-glycosides (vitexin, isovitexin), flavones (e.g. luteolin),

isoflavones, glycoflavones, cyanidin, delphinidin, catechines, anthocyanins or

betalains (betacyanins, e.g. amaranthin, celosianin, betamin, phyllocactin, and

betaxanthins), oleanolic acid derivatives, sterols, methylated and

non-methylated ellagic acids, gallic acid, tannins, proanthocyanidins

(prodelphinidins), mesembrine, tyramine alkaloids, phenethylamines, peyote

alkaloids, indole alkaloids, tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids, acetogenic

benzylisoquinoline alkaloids, naphthyl-isoquinoline alkaloids (e.g.,

ancistrocline, dioncophylline, michellamines), cyanogenic compounds (e.g.

cyclopentenoid cyanogenic glycosides), betaine, triterpene saponins,

anthraquinones, acetophenones, naphthoquinones and naphthoquinone derivatives

(plumbagin, droserone, 5-O-methyl droserone, 7-methyljuglone,

hydroxyserone; toxic naphthoquinones and their derivatives act as antimicrobial

protectors and at least plumbagin as an insect ecdysis inhibitor e.g. in the

pitchers of Nepenthes), simmondsin, fagopyrine, protofagopyrine,

syringaresinol, oxalic acid, phytoferritin, phytoecdysones, cyclopeptides, and

pinitol present. Ferulic acid often present in non-lignified cell walls. Inulin

rarely present. Sulphated betalains present in the clade [Phytolaccaceae+ Petiveriaceae+Agdestis].

Benzylisoquinoline alkaloids and betalains both derived via shikimic acid

(especially phenylalanine) pathway.

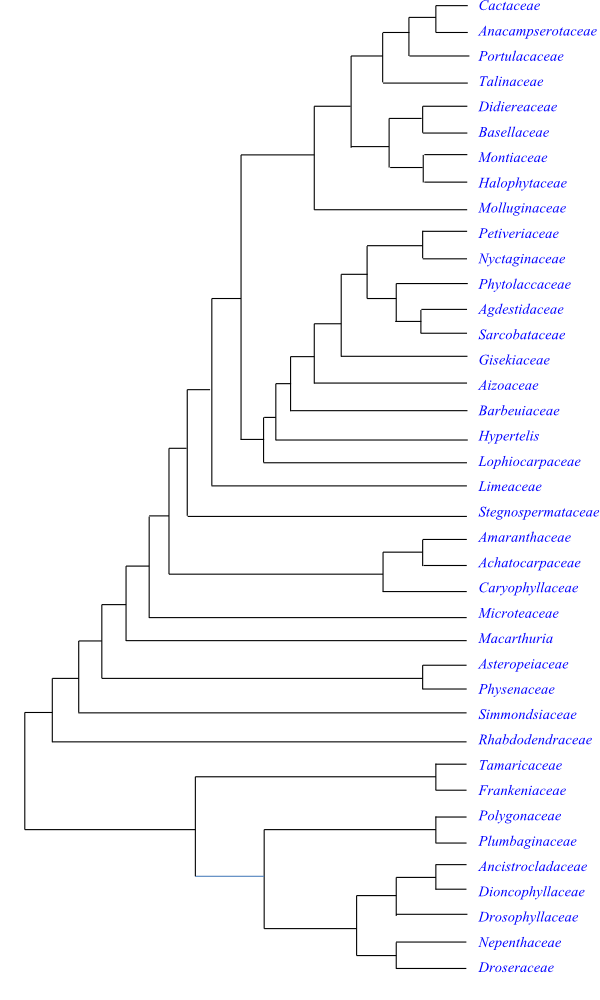

Systematics Caryophyllales are

sister-group to Berberidopsidales.

Two strongly supported main clades can be

discerned. One large monophyletic group comprises “the carnivorous clade”

plus [[Tamaricaceae+Frankeniaceae]+[Polygonaceae+Plumbaginaceae]]. The

second main clade includes [Rhabdodendraceae+[Simmondsiaceae+[Asteropeiaceae+Physenaceae]]] plus the core

Caryophyllales in

the strict sense.

Potential synapomorphies of the first main

clade are according to Stevens (2001 onwards): presence of pit glands;

endosperm starchy; and presence of acetogenic naphthoquinones. The first of the

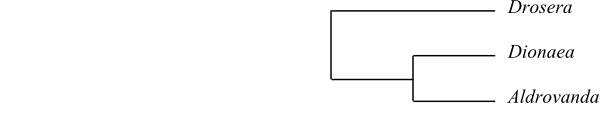

two subclades, “the carnivorous clade”, has the topology [[Droseraceae+Nepenthaceae]+[Drosophyllaceae+[Ancistrocladaceae+Dioncophyllaceae]]] and

is characterized by the following potential synapomorphies: presence of

vascularized multicellular glands; cymose inflorescence; corolla with contorted

aestivation; extrorse anthers; unilocular ovary; and presence of plumbagin

present. A clade identified in some analyses has the topology [Nepenthaceae+[Drosophyllaceae+[Ancistrocladaceae+Dioncophyllaceae]]] and

the synapomorphies: presence of fibriform vessel elements; wood rays one or two

cells wide; leaf vernation abaxially circinate; petiole vascular bundles

surrounded by massive sclerenchymatous cylinder with embedded bundles; presence

of wing bundles; and basifixed anthers. Ancistrocladaceae and

Dioncophyllaceae

share the following characters: climbing woody habit; phellogen deeply seated;

absence of cortical vascular bundles; petiole with inverted vascular bundles in

sclerenchyma cylinder; actinocyclocytic stomata; introrse anthers; and

acetogenic naphthyl isoquinoline alkaloids biosynthesized from polyketides (not

from aromatic amino acids).

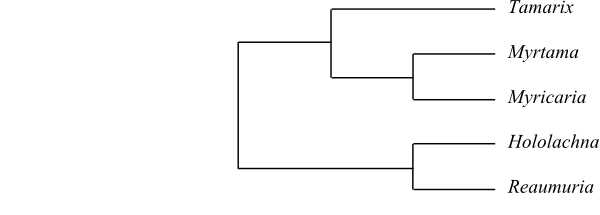

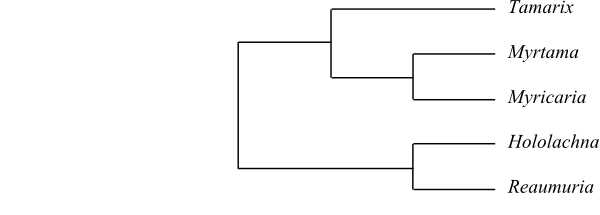

The clade [[Frankeniaceae+Tamaricaceae]+[Plumbaginaceae+Polygonaceae]] is sometimes

discerned and has the potential synapomorphies (Stevens 2001 onwards): vessel

elements with minute lateral wall pits; outer and inner integuments two or

three cell layers thick; exotestal seed coat; and presence of sulphated

flavonols and ellagic acid. Frankeniaceae and Tamaricaceae share the

characters: wood storied; halophytic habit with small leaves covered by

salt-excreting glands; flowers small, tetra- to hexamerous; petals with basal

adaxial appendages; exine not spinulate; median carpel abaxial; placentation

usually parietal; loculicidal capsule; exotestal cells bulging or as hairs;

presence of endosperm; presence of bisulphated flavonols; and absence of

myricetin. Plumbaginaceae and Polygonaceae share the

synapomorphies: wood storied; absence of successive cambia; presence of

cortical and/or medullary vascular bundles; nodes 3:3; wide leaf bases; pollen

grains usually starchy; median carpel adaxial; ovary unilocular; placentation

basal; ovule one per carpel; fruit an anthocarp surrounded by accrescent calyx

forming part of dispersal unit; seed coat indistinguished except persistent

exotesta; loss of mitochondrial intron coxII.i3; and presence of

O-methylflavonols, myricetin and quinones.

The second main clade has the topology [Rhabdodendraceae+[Simmondsiaceae+[[Asteropeiaceae+Physenaceae]+[Macarthuriaceae+[Microteaceae+[[Caryophyllaceae+[Achatocarpaceae+Amaranthaceae]]+[Stegnospermataceae to

Cactaceae]]]]]]] and the

potential synapomorphies (Stevens 2001 onwards): filament much shorter than

anther; stylodia stigmatic (receptive) their entire length; ovules one or two

per carpel; fruit single-seeded; and endosperm sparse. This clade minus

Rhabdodendron is characterized by nodes 1:1 and absence of petals.

Asteropeia and Physena lack successive cambia; have a

vascular cylinder in the young stem; fibre tracheids; vasicentric tracheids;

wood rays one or two cells wide; aliform-confluent axial parenchyma; latrorse

anthers; and one-seeded fruit.

The core Caryophyllales – “the

betalain clade” – comprise [Macarthuriaceae+[Microteaceae+[[Caryophyllaceae+[Achatocarpaceae+Amaranthaceae]]+[Stegnospermataceae to

Cactaceae]]]]. Hence,

they include the caryophyllids in the traditional strict sense. It is a group

with very high bootstrap support and characterized by a large number of

potential synapomorphies (Stevens 2001 onwards): herbaceous habit; absence of

normal secondary lateral growth; CAM photosynthesis and C4

photosynthesis frequently present; sieve tube plastids P-type, with a central

angular protein crystal surrounded by a ring of protein filaments; absence of

pericyclic fibres; cymose inflorescence; presence of adaxial nectaries on

stamen bases; pollen grains tricellular at dispersal; exine with thin foot

layer; median carpel adaxial; ovary unilocular; stigmas papillate; placentation

free central or basal; ovules campylotropous; thickened exotestal and

endotegmic cells; endotegmic cells with bar-like thickenings; perisperm well

developed; absence of endosperm; starch grains clustered; embryo curved and

periferal; cotyledons incumbent; absence of mitochondrial gene rps10;

absence of plastid gene rpl2 intron; ferulic acid ester-linked to

unlignified primary cell walls; presence of flavonols and O-methylated

flavonols, quinones, usually betalains (chromoalkaloids) instead of

anthocyanins, triterpenoid saponins and phytoferritin; and absence of tannins

and myricetin. Usually phenylalanine-derived shikimic acid biosynthesis as

starting point for synthesis of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids and betalains. An

undifferentiated perianth evolved after the separation of the

Rhabdodendron lineage, and a differentiated perianth may have

originated at least nine times (Brockington & al. 2009):

Asteropeia, Caryophyllaceae,

Stegnosperma, species of Limeum, Corbichonia,

Mesembryanthemoideae and Ruschioideae in Aizoaceae, Mirabilis

in Nyctaginaceae,

Glinus in Molluginaceae,

Portulaca, Didiereaceae, Basellaceae, and Cactaceae.

The clade [Caryophyllaceae+[Achatocarpaceae+Amaranthaceae]] has the

potential synapomorphies: stamens as many as tepals, antetepalous; a single

ovule; parietal tissue approx. four cell layers thick; nucellar cap two to four

cell layers thick; especially outer exotestal cell walls thick, with

stalactite-like processes; mitochondrial genes rps1 and rps19

absent (lost); and often presence of phytoecdysteroids.

The lineages “above” Stegnosperma

are characterized by apotropous ovules. “The globular inclusion clade”

comprises Lophiocarpaceae to Cactaceae and posesses sieve

tube plastids with globular crystalloids. The clade comprising Sarcobataceae, Nyctaginaceae, Agdestidaceae, Phytolaccaceae and Petiveriaceae often forms

an unresolved polytomy (sometimes also including Gisekiaceae). It is

characterized by a single usually basal ovule per carpel; similarities in

ORF2280 sequence; and a 210 bp deletion in the plastid genome. They have

usually (Sarcobatus?) a subepidermal phellogen; also paracytic

stomata; and protein bodies in the nucleus. This clade minus Nyctaginaceae has racemose

inflorescence and a baccate fruit.

The second large clade of “the globular

inclusion lineage” comprises Molluginaceae to Cactaceae. The clade with the

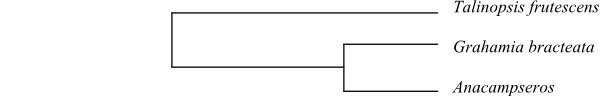

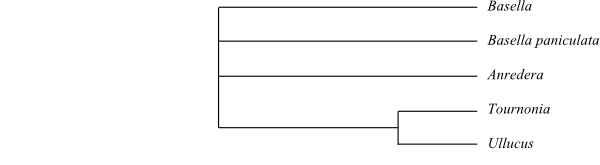

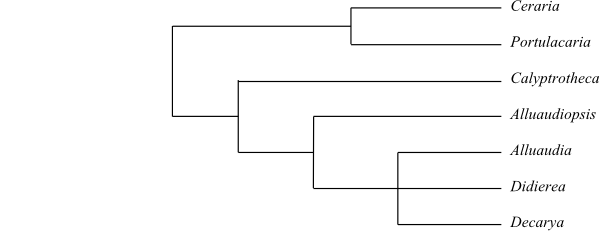

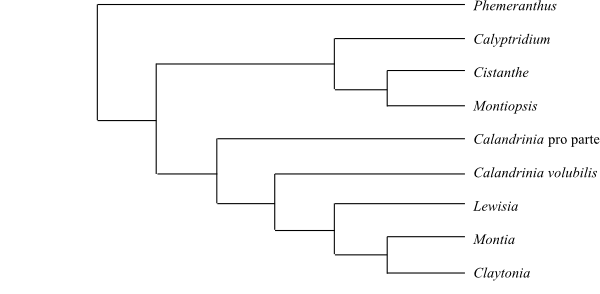

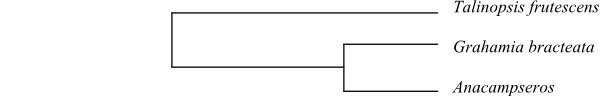

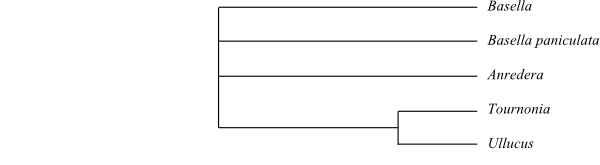

topology (Brockington & al. 2013) [[[Montiaceae+Halophytaceae]+[Didieraceae+Basellaceae]]+[Talinaceae+[Portulacaceae+[Anacampserotaceae+Cactaceae]]]]

(Portulacineae, of Nyffeler & Eggli 2010; Cactineae of

Ocamp & Columbus 2010) has the following potential synapomorphies,

according to Stevens (2001 onwards): succulent leaves and/or stem; normal

secondary lateral growth; phloem parenchyma cells with phytoferritin; stem

epidermis with calciumoxalate crystals; presence of mucilage cells; leaves

amphistomatic; median inner pair of floral prophylls enclosing flower;

hypogyny; petaloid tepals; median tepal abaxial (opposite outer median floral

prophyll); pollen grains pantocolpate; absence of funicular obturator; and a

six bp deletion in plastid gene ndhF. The clade [Talinaceae+[Portulacaceae+[Anacampserotaceae+Cactaceae]]] is further

characterized by columellae narrowed towards middle or expanded towards base,

sometimes fused; pollen grains with granular internal surfaces; perforated foot

layer; and very thin non-apertural endexine (Nowicke 1996). Halophytaceae, Basellaceae and Didiereaceae sometimes form

a monophyletic group, with Halophytum sister to the remainder.

Potential synapomorphies are ovary with a single basal ovule; and a

single-seeded indehiscent fruit. Basellaceae may be

sister-group to Didiereaceae or even nested

within that clade (Didiereaceae and Basellaceae have often

paracytic stomata). In this case, Halophytum may be sister to Didiereaceae including

Basellaceae.

The monophyletic group [Talinaceae+[Portulacaceae+[Anacampserotaceae+Cactaceae]]] is supported by

the potential synapomorphies (Stevens 2001 onwards): presence of mucilaginous

cells; absence of pericyclic fibres; leaves with axillary uniseriate, biseriate

or multiseriate hairs, bristles or scales; stomata parallelocytic (stoma with a

lateral series of at least three alternating subsidiary cells increasing in

size away from guard cells; also present in Montiaceae); pericarp

two-layered; fruit covered by dry tepals; exocarp completely or almost

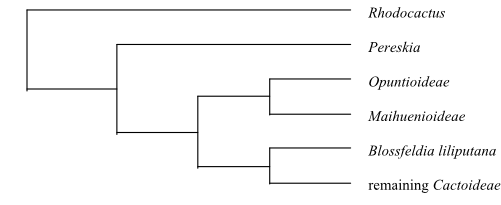

caducous. Portulacaceae and Cactaceae may be sister-groups,

according to Ocampo & Columbus (2010), using data mainly from non-coding

plastid DNA. Portulaca and at least Pereskia share, e.g., a

c. 500 bp deletion in rbcL, and non-lignified parenchyma cells are

sometimes present in the wood in Portulaca and Cactaceae. On the other hand,

Nyffeler & Eggli (2010), using sequence data from matK and

ndhF, identified Anacampserotaceae and

Cactaceae as

sister-groups (they share among morphological features the character of

numerous stamens). A special arrangement of testa cells along the dorsal

juncture, presence of a dry aril and a central field type of cuticular

ornamentation are characteristic features in several clades of Caryophyllales such as

Cactaceae and Portulacaceae (Barthlott

1984).

A characteristic feature of the “ACPT

clade” (Talinaceae,

Portulaca, Anacampserotaceae and

Cactaceae) are the

non-vascularized hair-, bristle- or scale-like trichomes present at the nodes

in the leaf axils (sometimes on internodes or on the lamina) (Ogburn &

Edwards 2009). They arise from the epidermis and are persistent. The hair-like

trichomes are either uniseriate or multiseriate (three or more cells in width).

The bristle-like trichomes are wide, flat and multiseriate (up to more than 20

cells in width). The species in Anacampseros sect. Avonia

possess wide scale-like trichomes which entirely surround the leaf distal to

the subtending leaf; these scales are apically lignified. Bristle-like

trichomes have been reported from species in Anacampserotaceae,

whereas hair-like trichomes are present in Portulaca, Anacampserotaceae and

Cactaceae. Membranous,

often paired, scale-like trichomes are present in Talinum (Talinaceae). They have often

been interpreted as homologous with the axillary trichomes, although they seem

to be apices of vascularized prophylls subsequently often developing into

leaves (Ogburn & Edwards 2009).

Problems concering homologies of the perianth

parts are notorious in Caryophyllales. A

uniseriate perianth is most probably plesiomorphic in Caryophyllales, and the

uniseriate floral organs may be homologous (Brockington & al. 2009). A

perianth may have originated by formation of homologous organs (perhaps in most

lineages of Caryophyllales), or by

differentiation of structures derived either from the androecium (in

Corbichonia in Lophiocarpaceae, in the

[Mesembryanthemoideae+Ruschioideae] clade of Aizoaceae, and in Molluginaceae) or from

bracts (in Nyctaginaceae and in the

“ACPT” clade), whereas ‘petaloid staminodia’ refer to floral parts that

are anambiguously derived from the androecium. The terms ‘sepaloid tepals’

and ‘petaloid tepals’ are applied to floral organs (with

quincuncial-imbricate aestivation) present in the core clade of Caryophyllales

(Brockington & al. 2009). ‘Petaloid tepals’ in Caryophyllaceae,

Stegnosperma, and Limeaceae have often been

interpreted as modified stamens (e.g. Ronse De Craene 2007, 2008, etc.).

|

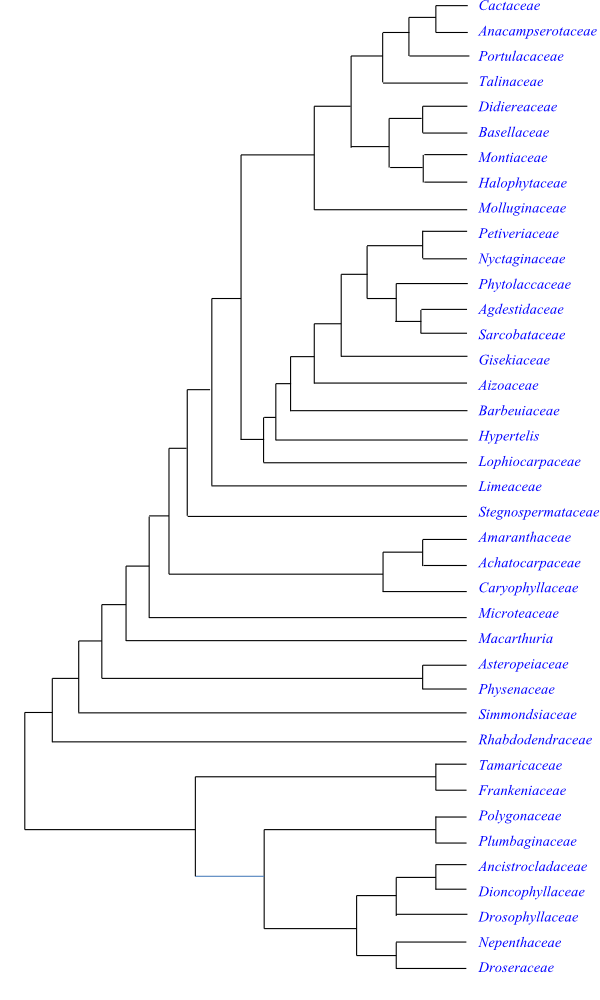

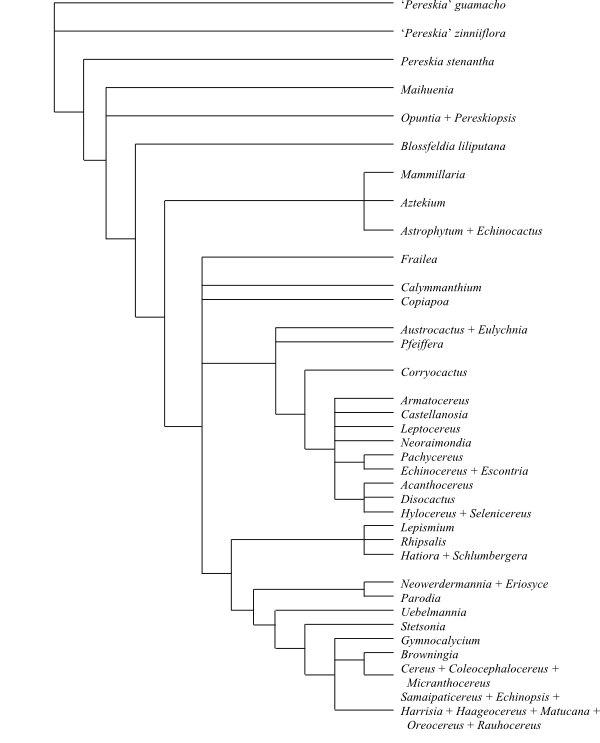

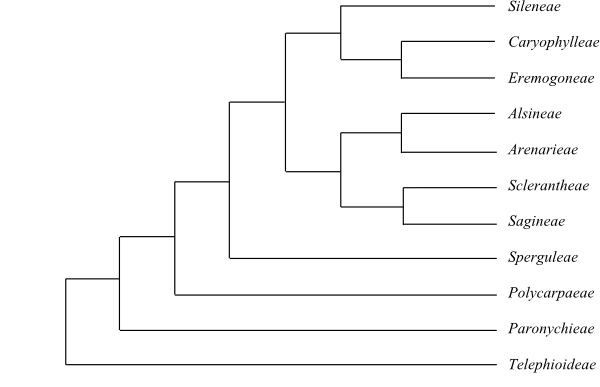

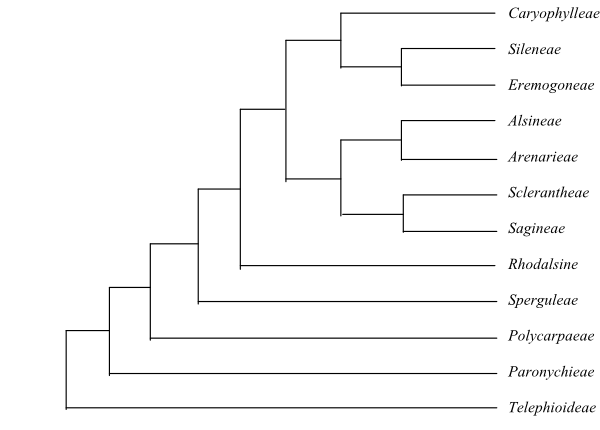

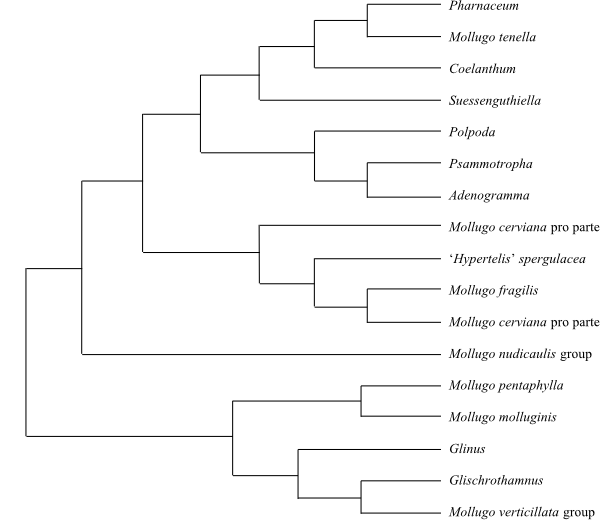

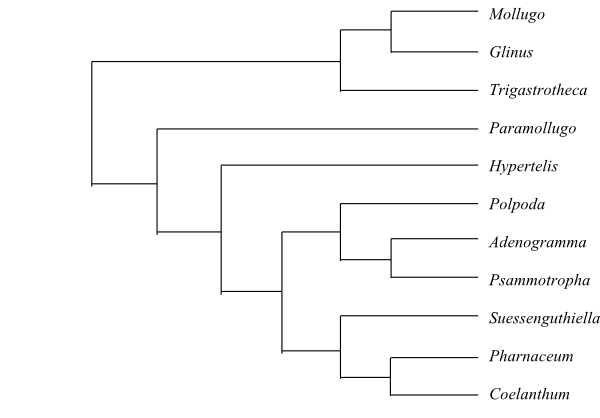

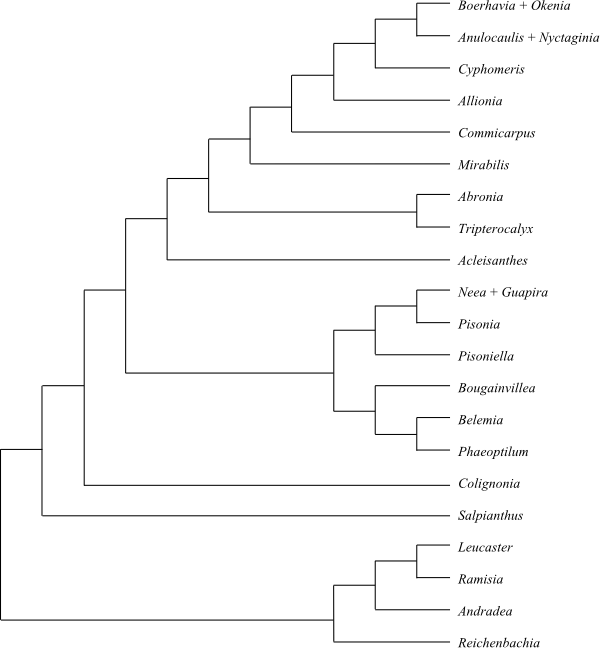

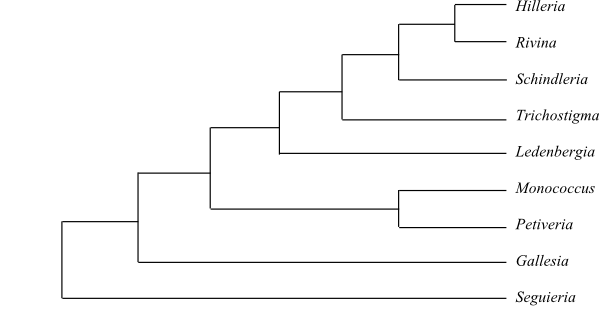

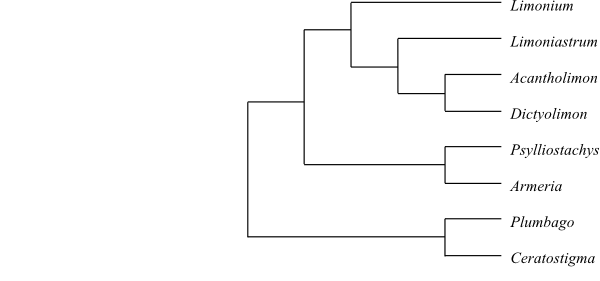

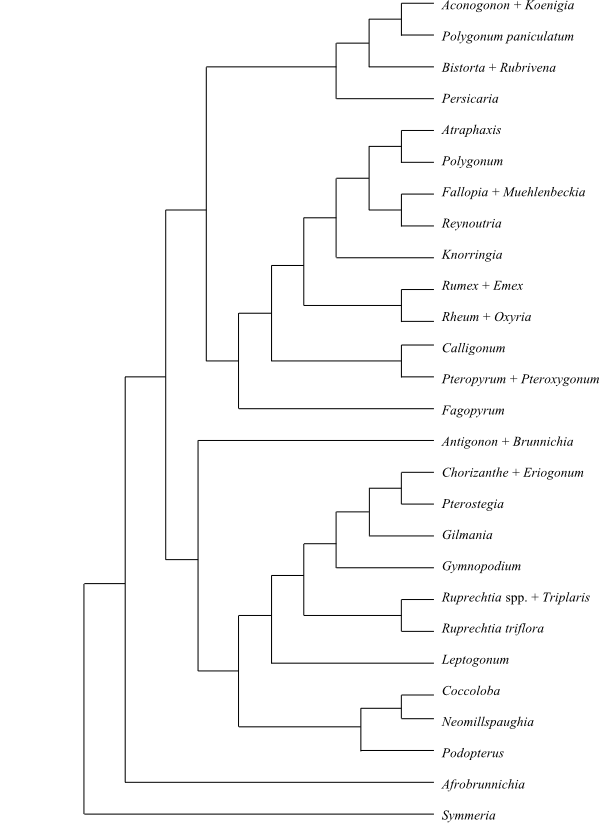

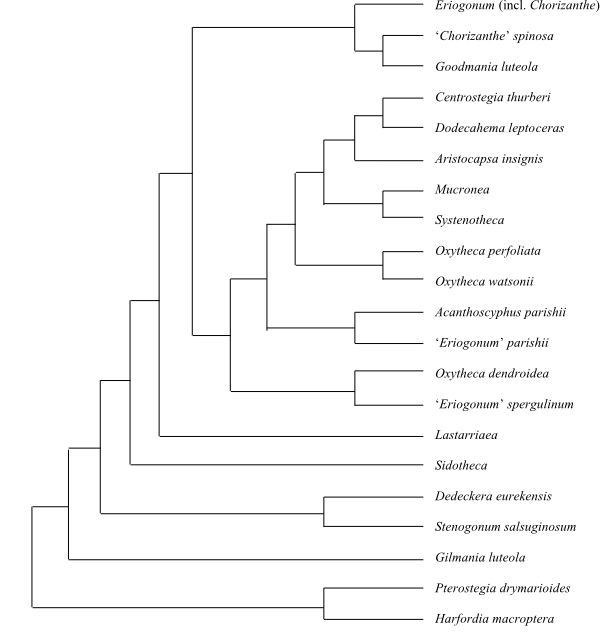

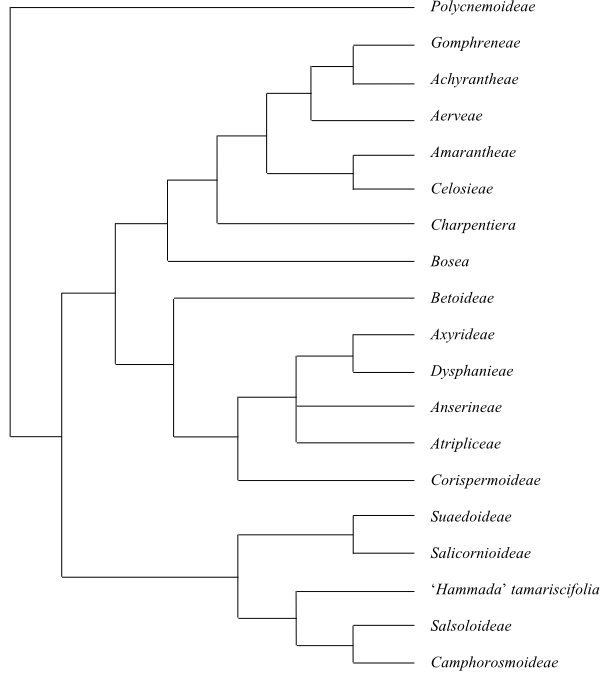

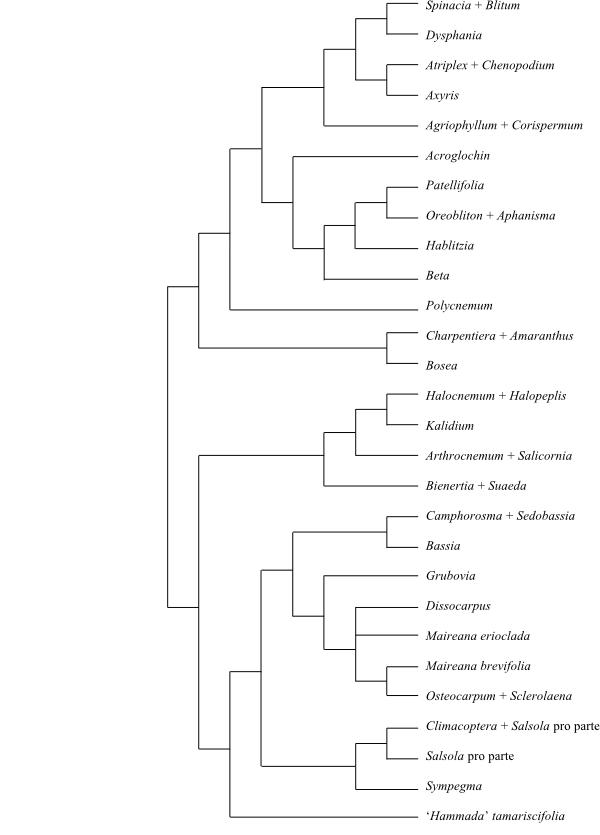

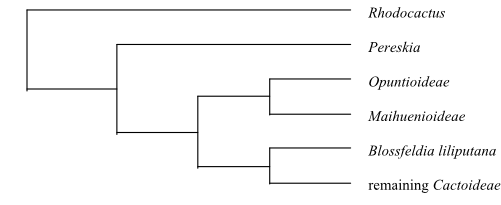

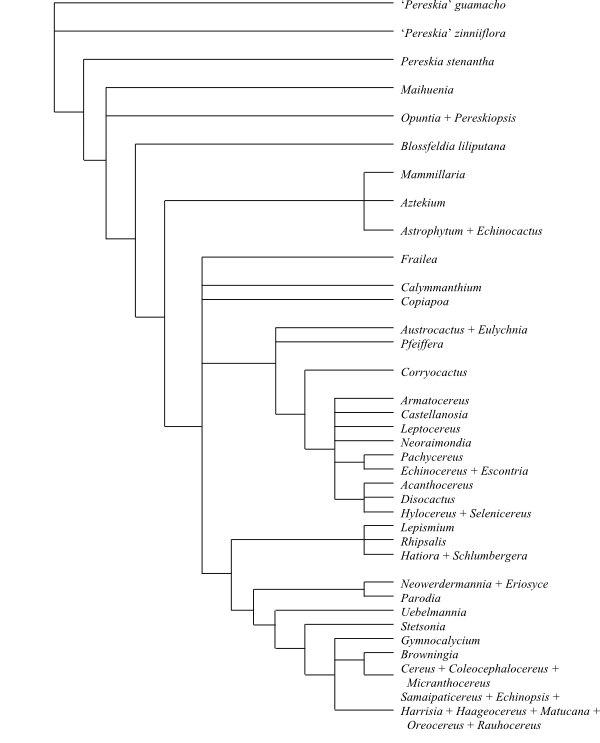

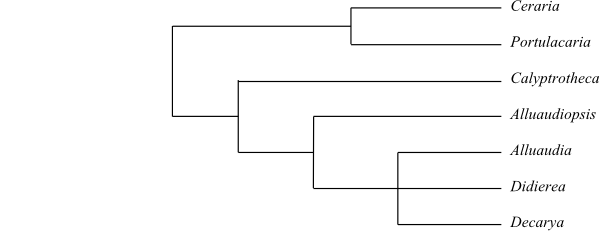

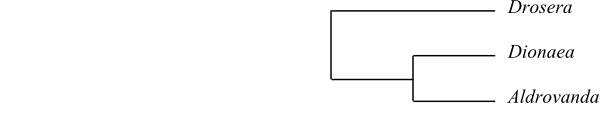

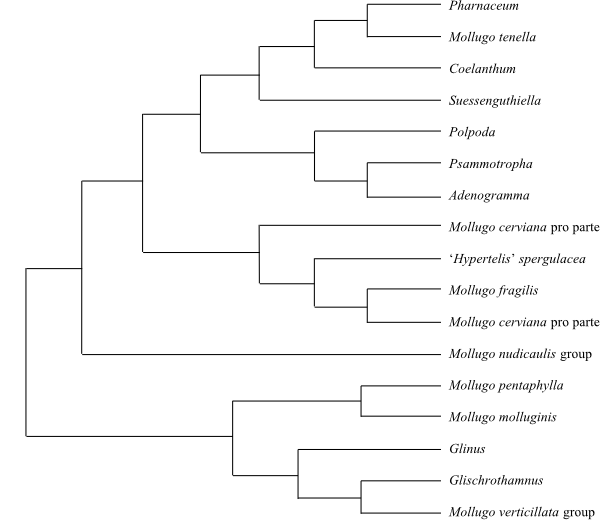

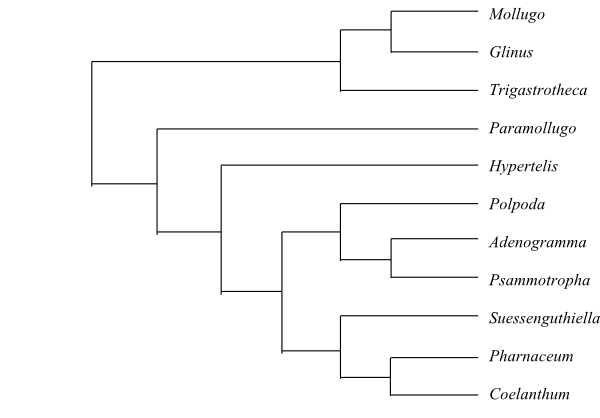

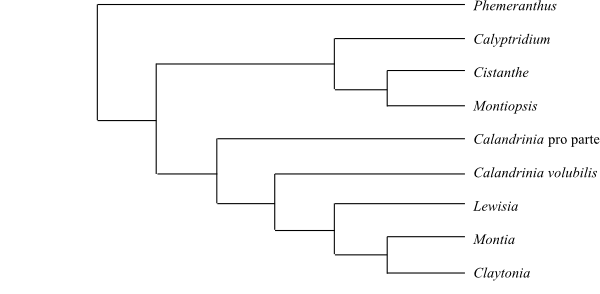

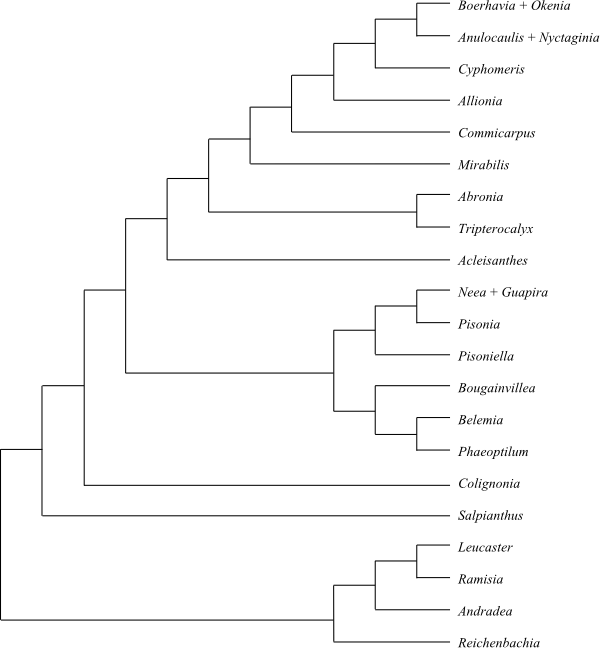

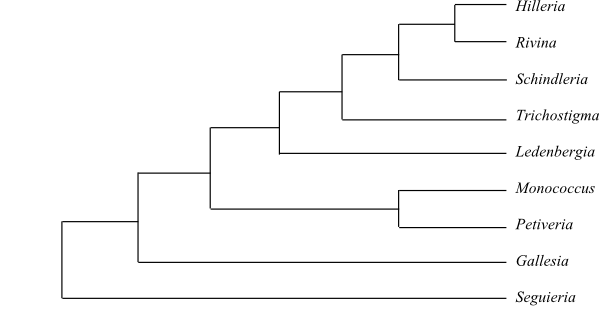

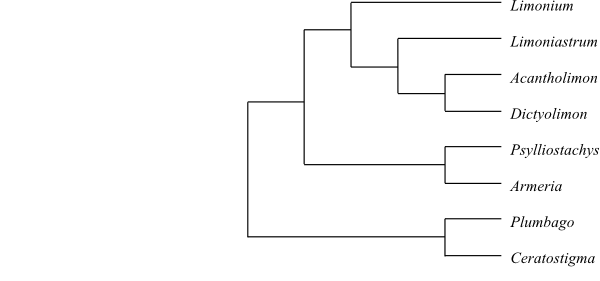

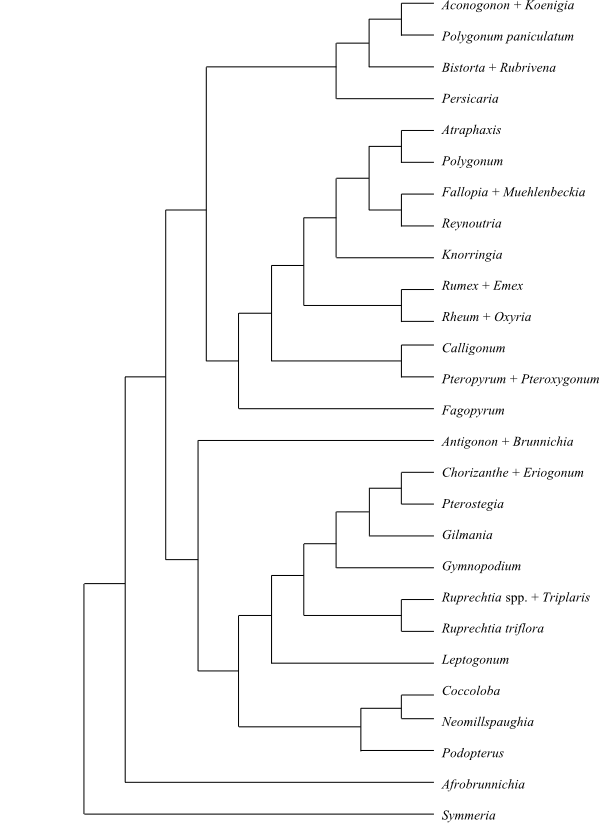

Phylogeny of Caryophyllales

based on DNA sequence data (“core Caryophyllales”

– Caryophyllineae: Brockington & al. 2013; “basal

Caryophyllales”

– Polygonineae: Brockington & al. 2009).

‘Hypertelis’ on this tree (according to Brockington &

al. 2013) is now synonymous with Kewaceae, whereas the

monospecific Hypertelis s. str. (H. spergulacea) is

nested inside Molluginaceae>

(Christenhusz & al. 2014).

|

Heimerl in Engler et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam.,

ed. 2, 16c: 174. Jan-Apr 1934, nom. cons.

Genera/species 2/c 11

Distribution California,

Texas, Mexico to Paraguay and Argentina.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Dioecious, evergreen

trees or shrubs. Apices of short shoots often modified into spines.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

ab initio superficial. Phelloderm with thick-walled sclereid cells. Secondary

lateral growth normal (successive cambia absent). Vessel elements with simple

perforation plates; lateral pits opposite or alternate, simple pits.

Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform fibres with simple pits. Wood

rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial

parenchyma (paratracheal) scanty vasicentric. Wood non-storied. Pericycle with

sclerenchyma and stone cells. Phloem fibres present (scattered in older

secondary phloem). Sieve tube plastids P3c’f type, with a single polygonal

central protein crystal and a subperipheral dense ring of protein fibrils.

Nodes? Tanniniferous cells often present. Calciumoxalate druses, sphaerites and

prismatic crystals present (raphides and styloids absent).

Trichomes Hairs absent on

older individuals; younger individuals with short hairs.

Leaves Alternate (spiral),

simple, entire, with ? ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole

vascular bundles? Venation pinnate. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax

crystalloids as lobed platelets (often arranged in groups). Leaf margin

entire.

Inflorescence Axillary,

raceme-like, fasciculate or panicle. Foliar prophylls (bracteoles) absent in

Achatocarpus.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small.

Hypogyny. Tepals five (Achatocarpus) or usually four (rarely five;

Phaulothamnus), with imbricate quincuncial (Achatocarpus) or

decussate (Phaulothamnus) aestivation, sepaloid, free. Nectary absent.

Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens ten to 20

(Achatocarpus) or twelve to 14 (Phaulothamnus). Filaments

thin, free or connate at base. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile,

tetrasporangiate, extrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits).

Tapetum secretory? Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous? Pollen grains tetraporate to hexaporate or

apertures more or less irregular and often little delimited, shed as monads,

?-cellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum,

microperforate, scabrate (beset with microspinules) or coarsely granulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

two usually free carpels (sometimes slightly connate at base), collateral or

superposed. Ovary superior, unilocular. Stylodia two, long, hairy and

papillate, free or connate at base. Stigmas two, acute, hairy and papillate,

type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation basal.

Ovule usually one (rarely two) per ovary, campylotropous, ascending, bitegmic,

crassinucellar. Funicle present. Micropyle ?-stomal. Outer integument ? cell

layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Parietal tissue?

Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type? Endosperm development?

Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A usually one-seeded

(occasionally two-seeded) berry.

Seeds Aril tiny (present at

hilum). Testa? Outer exotestal wall with stalactite-shaped outgrowths? Tegmen?

Perisperm copious, mealy. Endosperm rudimentary or absent. Embryo annular,

peripheral, enclosing perisperm, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Germination?

Cytology n = ?

DNA

Phytochemistry

Flavone-C-glycosides (vitexin, isovitexin) and tannins present.

Anthocyanin and betalains? Ferulic acid in non-lignified cell-walls? Ellagic

acid not found.

Use Medicinal plants.

Systematics

Achatocarpus (c 10; southern Mexico to Paraguay and Argentina),

Phaulothamnus (1; P. spinescens; California, Texas, northern

Mexico, Tres Marias Islands).

Nakai in J. Jap. Bot. 18: 104. 10 Mar 1942

Genera/species 1/1

Distribution Southern United

States to Nicaragua.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, evergreen,

more or less lignified liana. Roots often napiform.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

ab initio subepidermal. Secondary lateral growth anomalous (via

concentric/successive cambia). Vascular bundles present as concentric cylinders

in inner pericycle. Vessel elements with simple perforation plates; lateral

pits alternate, simple pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform

fibres and tracheids with simple pits, septate or non-septate (also vasicentric

tracheids). Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma apotracheal, diffuse, or

paratracheal. Wood non-storied. Tyloses sometimes present in vessels. Sieve

tube plastids P3cf type, with a central globular protein crystal surrounded by

a ring of protein filaments. Nodes? Parenchyma with idioblasts containing

calciumoxalate as coarse raphide-like crystals.

Trichomes Hairs?

Leaves Alternate (spiral),

simple, entire, with conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent.

Petiole twisted at base. Petiole vascular bundles? Venation pinnate. Stomata

anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids as rounded platelets. Idioblasts with

calciumoxalate as coarse raphide-like crystals. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Axillary,

thyrsoid or panicle. Foliar prophylls (bracteoles) present.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small.

Half epigyny. Tepals usually four (in terminal flowers sometimes five), with

imbricate? aestivation, sepaloid, persistent, usually free (sometimes connate

at base). Nectariferous disc narrow.

Androecium Stamens (twelve to)

15 to c. 30, in alternitepalous fascicles. Filaments filiform, usually connate

at base (sometimes free), free from tepals, inserted at nectariferous disc.

Anthers dorsifixed, versatile?, tetrasporangiate, introrse, longicidal

(dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains tricolpate, shed as monads,

tricellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum, punctate

or perforate, scabrate, spinulate or smooth.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

(three or) four connate carpels. Ovary semi-inferior, ab initio (trilocular or)

quadrilocular, later usually unilocular by degeneration of remaining locules.

Style single, simple, short, cylindrical. Stigma (trilobate or) quadrilobate,

recurved, papillate on ventral side, type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation basal to

axile. Ovule one per carpel, hemianatropous (or campylotropous?), bitegmic,

crassinucellar. Micropyle ?-stomal. Outer integument ? cell layers thick. Inner

integument ? cell layers thick. Parietal tissue approx. two cell layers thick.

Hypostase present. Nucellar cap massive. Megagametophyte monosporous,

Polygonum type. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm

haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A one-seeded unilocular

achene with wings formed by persistent and accrescent dry tepals. Pericarp

coriaceous, with reticulate pattern, adnate to seed coat.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa?

Tegmen? Perisperm probably copious and nutritious. Endosperm poorly developed

or absent. Embryo peripheral, curved around perisperm, well differentiated,

chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Germination?

Cytology n = 9 – Cell nuclei

with protein bodies?

DNA 210 bp deletion present in

plastid DNA?

Phytochemistry Betacyanins and

betaxanthins present. Proanthocyanidins and alkaloids not found. Triterpenoid

saponins? Free oxalates accumulated?

Use Medicinal plant,

ornamental plant.

Systematics Agdestis

(1; A. clematidea; southern United States, Mexico, Central America

southwards to Nicaragua, probably introduced in the West Indies and Brazil).

Agdestis is sister to Sarcobatus,

according to Brockington & al. (2013).

Martinov, Tekhno-Bot. Slovar: 15. 3 Aug 1820

[’Aizoonides’], nom. cons.

Mesembryanthemaceae

Philib., Intr. Bot., ed. 2, 3: 268. 20 Dec 1801, [‘Mesembraceae’],

nom. rejic.; Galeniaceae Raf. in Amer. J. Sci. 1:

376. Mai-Dec 1819; Mesembryaceae Dumort., Anal. Fam.

Plant.: 37, 41. 1829 [‘Mesembryneae’];

Mesembryanthemales Link, Handbuch 2: 12. 4-11 Jul

1829 [‘Mesembrinae’]; Sesuviaceae

Horan., Prim. Lin. Syst. Nat.: 83. 2 Nov 1834 [‘Sesuviaceae

(Ficoideae)’]; Tetragoniaceae Lindl.,

Intr. Nat. Syst. Bot., ed. 2: 209. 13 Jun 1836, nom. cons.;

Aizoales Boerl., Handl. Fl. Nederl. Ind. 1: li. 2 Aug

1890; Aizoineae Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.:

xli. 23 Dec 2001

Genera/species

124/1.675–1.695

Distribution Arid tropical and

subtropical regions including western and southern Australia, with their

highest diversity in southern and southwestern Africa.

Mesembryanthemoideae and, above all, Ruschioideae dominate

much of the succulent vegetation in the Karroo areas of South Africa, where

they constitute more than half the number of species and more than 90% of the

biomass.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Usually bisexual (rarely

monoecious or dioecious), perennial or annual herbs (rarely climbing),

suffrutices or shrubs. Usually leaf succulents (sometimes stem succulents,

rarely root succulents; some species are almost entirely subterranean). Almost

all representatives are xerophytes; some species are halophytes. C4

or CAM (rarely C3) physiology present. Kranz’ anatomy present in

some species. Usually mucilaginous.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza

usually absent. Kranz’ anatomy present in some species. Phellogen ab initio

inner-cortical or endodermal, or absent. Primary medullary strands wide.

Medullary wide-band tracheid cells frequent, also present in foliar tissue

other than mid-vein; bands narrow yet very tall, cell lumen in places very

narrow. Endodermis significant. Secondary lateral growth normal or sometimes

anomalous (via concentric/successive cambia) or absent. Vessel elements usually

with simple perforation plates; lateral pits alternate? Imperforate tracheary

xylem elements libriform fibres with bordered pits? (in at least one species of

Ruschia also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays usually absent (present

in Tetragonia). Axial parenchyma paratracheal? (in Tetragonia

also vasicentric). Wood elements often partially storied. Sieve element

plastids P3cf type, with a central globular protein crystal surrounded by

protein filaments. Nodes 1:1, unilacunar with one leaf trace, or 3:3,

trilacunar with three traces. Tanniniferous idioblasts often present in

water-storing tissue. Epidermis in many species with densely spaced

water-storing vesicular idioblasts with wide base. Calciumoxalate crystals

often present.

Trichomes Hairs usually

unicellular or multicellular and uniseriate (rarely stipitate, two-branched or

stellate), often vesicular, or absent.

Leaves Usually opposite (often

pairwise fused; sometimes alternate), simple, entire, often cuboidal, conical,

cylindrical or prismatic, with usually curved or flat ptyxis. Stipules usually

absent (petiole base in Sesuvioideae with stipule-like appendages);

leaf bases often membranous and sheathingly connate around stem (sometimes

entirely connate). Petiole vascular bundles forming cortical reticulum.

Venation pinnate or palmate, usually indistinct, with sunken main veins.

Stomata anomocytic, paracytic or anisocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids as

rodlets (often terete), threads or platelets. Mesophyll sometimes with

idioblasts containing calciumoxalate raphides. Epidermis of upper side of

lamina often with numerous water-storing wide-based vesicular idioblasts. Outer

epidermal cell walls often with calciumoxalate crystals. Leaf margin entire,

dentate or serrate.

Inflorescence Terminal (often

seemingly axillary), cymose (sometimes capitate), or flowers usually solitary

terminal. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) usually large, often foliaceous.

Flowers Actinomorphic, often

large. Hypanthium usually present. Hypogyny, half epigyny or epigyny. Tepals

(three to) five (to eight), in one whorl, with usually imbricate quincuncial

(rarely valvate) aestivation, usually sepaloid (adaxial tepals sometimes

petaloid), persistent, connate at base, often with subapical abaxial appendage.

Nectary usually continuous, annular on adaxial side of perianth-stamen tube

(nectaries in Mesembryanthemoideae partially tubular). Disc present or

absent.

Androecium Stamens usually

numerous (to more than 2.000; sometimes four, five, eight, or ten), in one or

more whorls or in three to nine groups; staminal primordia five,

alternitepalous, or as annular meristem. Outer whorls usually consisting of

petaloid staminodia, inner whorls consisting of fertile stamens, median whorls

often intermediary. Filaments free or connate (all or in three to nine groups),

free from tepals. Anthers dorsifixed, often versatile, tetrasporangiate,

introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory, with

usually trinucleate (rarely septanucleate) cells. Staminodia petaloid,

extrastaminal, usually numerous (absent in some genera).

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tricolpate (rarely

tetracolpate or tricolporoidate), shed as monads, tricellular at dispersal.

Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, perforate, punctate

or anulopunctate, spinulate (rarely reticulate or rugate).

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

(one or) two to five (to numerous) connate carpels. Ovary superior to inferior,

(unilocular or) bilocular to quinquelocular (to multilocular), usually entirely

septate (septa in Acrosanthes incomplete). Stylodia usually free

(rarely connate). Stigmatic areas adaxial, papillate, Dry or Wet type.

Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation usually

axile (in early stage, primary; rarely basal or apical) to parietal (in later

stage, secondary). Ovules one to numerous per carpel (in Acrosanthes a

single basal ovule per carpel), campylotropous (hemianatropous?) to

anacampylotropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal. Outer

integument two or three cell layers thick. Inner integument two cell layers

thick. Obturator placental. Parietal tissue approx. three cell layer thick.

Nucellar cap micropylar. Apical cells of megasporangium often radially

elongate. Megagametophyte usually monosporous, Polygonum type (rarely

Endymion, Penaea, Drusa, or Adoxa type).

Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria chalazal?

Embryogenesis caryophyllad or solanad.

Fruit Usually a loculicidal

capsule (sometimes a nut, rarely a pyxidium, a berry or a schizocarp; in

Gunniopsis a septicidal capsule), usually hydrochastic, dehiscing in

moist weather, when septa and other tissues swell (septal keels, reaching from

central axis to valve apices).

Seeds Aril sometimes present

(surrounding seed in Sesuvioideae). Exotesta palisade or tangentially

elongate. Endotesta and tegmen usually crushed. Perisperm copious, starchy.

Endosperm sparse or absent. Suspensor massive, usually biseriate to

multiseriate. Embryo peripheral, curved around perisperm, without chlorophyll.

Cotyledons two. Radicula dorsal. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology x = 8

(Sesuvioideae, Aizooideae); x = 9

(Mesembryanthemoideae, Ruschioideae) – Polyploidy

frequently occurring.

DNA Intron absent from plastid

gene rpoC1 (at least in Delospera and Faucaria).

Plastid gene infA transferred to nucleus (Mesembryanthemum;

pseudogene present in plastid genome).

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin), cyanidin, condensed tannins, betacyanins,

betaxanthins, mesembrine alkaloids (Phyllobolus etc.), and ferulic

acid (in non-lignified cell walls) present. C-glycosylflavonoids,

ellagic acid and saponins not found. Some species oxidize free oxalates.

Use Ornamental plants,

vegetables (Tetragonia tetragonioides), fruits (Carpobrotus

edulis), stabilization of soil (Carpobrotus etc.).

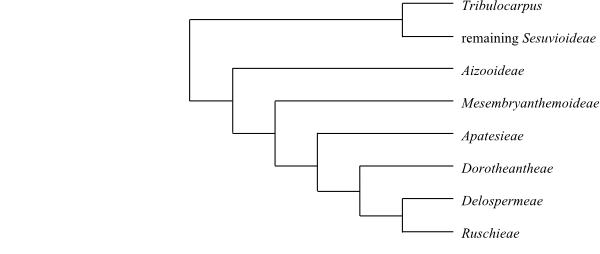

Systematics Aizoaceae are possibly sister

to a clade comprising Gisekia, Phytolaccaceae, Sarcobatus,

Agdestis, Nyctaginaceae, and Petiveriaceae.

There is strong bootstrap-support for the

following topology within Aizoaceae:

[Sesuvioideae+[Aizooideae+[Acrosanthoideae+[Mesembryanthemoideae+Ruschioideae]]]]

Sesuvioideae Lindl.,

Veg. Kingd.: 527. Jan-Mai 1846 [‘Sesuveae’]

6/63.

Anisostigmateae Klak in Taxon 66(5): 1167. 24 Oct

2017 Anisostigma (1; A. schenckii; Namibia),

Tribulocarpus (3; ‘T. dimorphanthus’ [non-monophyletic]:

Somalia, Namibia; T. retusus: Somalia);

Sesuvieae Fenzl in Ann. Wiener Mus. Naturgesch. 2:

289. 1839. Cypselea (3; C. humifusa, C. meziana,

C. rubriflora; southern Florida, the West Indies, Venezuela), Sesuvium (22;

tropical and subtropical coastal areas), Trianthema (27; Africa,

tropical and subtropical Asia, Australia, T. portulacastrum also in

northern South America), Zaleya (7; Z. camillei, Z.

decandra, Z. galericulata, Z. govindia, Z.

pentandra, Z. redimita, Z. sennii; northeastern and

eastern Africa, Madagascar, India, Sri Lanka, the Lesser Sunda Islands,

northern Australia). – Tropical and subtropical regions. C4

photosynthesis and Kranz’ anatomy present. Nodes 1:1 or 3:3. Stipules

petiolar. Inflorescence distinct from vegetative parts of plant. Prophylls

often prominent. Inflorescence bracteates, usually separated from vegetative

parts. Hypanthium often present. Nectary annular (holonectary). Stamens one to

five. Androecial primordia often antetepalous. Carpels (one or) two (to five),

alternitepalous. Ovules two to numerous per carpel. Fruit usually a pyxidium

(not a hygrochastic capsule). Seed glossy black, usually arillate.

Tribulocarpus, with a syncarpous fruit

fused with spiny bracts, and with non-arillate seeds, is sister to the

remaining Sesuvioideae.

[Aizooideae+[Acrosanthoideae+[Mesembryanthemoideae+Ruschioideae]]]

Inflorescence usually indistinct. Floral

prophylls foliaceous. Androecial primordia usually alternitepalous. Carpels

antetepalous. Fruit a hygrochastic capsule.

Aizooideae Spreng. ex

Arn., Botany: 112. 9 Mar 1832 [‘Aizoideae’]

5/c 100. Aizoanthemopsis (1;

A. hispanicum; the Mediterranean, northern Africa, the Middle East to

Iran), Gunniopsis (14; Australia except northern and eastern parts),

Tetragonia (c 50; southern Africa, Namibia, Morocco, Australia, New

Zealand, islands in the Pacific, temperate and subtropical South America, one

species, T. tetragonioides, worldwide), Aizoanthemum (4;

A. dinteri, A. galenioides, A. mossamedense, A.

rehmannii; southern Angola, northern Namibia), Aizoon (c 30;

southern Angola to South Africa, one species, A. canariense, in

Macaronesia, the Mediterranean, Zimbabwe, northern Kenya and Socotra to India).

– Drier parts of South Africa, South America, Australia

(Gunniopsis), a few species in North Africa, Southwest and East Asia.

Vesicular hairs with large vesicular terminal cell and multicellular stalk.

Accessory lateral branches often present. Inflorescence with leaves. Hypanthium

present. Hypogyny to epigyny. Nectary annular, continuous (holonectary),

present on apex of hypanthium. Stamens four to ten. Pistil composed of two to

ten connate carpels. Ovary superior to inferior. Ovule one per carpel, apical,

apotropous; or basal, several to numerous per carpel. Capsule usually a

loculicidal (in Gunniopsis a septicidal) capsule (in Tetragonia a

nutlet). Testal cell walls usually thickened (sometimes only little thickened).

Tetragonia

has a single pendulous ovule, megasporangium with druses, inner layer of the

inner integument well developed, and an indehiscent fruit. –

Aizoanthemopsis hispanicum is sister to the rest (Klak & al.

2017).

[Acrosanthoideae+[Mesembryanthemoideae+Ruschioideae]]

Leaves strongly succulent. Epigyny to

half epigyny. Nectary disrupted (meronectary). Stamens and petaloid staminodia

numerous. x = 9. – The androecial development is centrifugal. Basipetal

members become progressively more sterile and petaloid, and intermediates link

the outermost petals to the inner fertile stamens (Brockington & al. 2009).

Correspondingly, the outer pentamerous uniseriate perianth loses its petaloid

features and appears like a calyx.

Acrosanthoideae

Klak in Taxon 66(5): 1161. 24 Oct 2017

1/6. Ovules basal, shortly stipitate.

Capsule xerochastic, parchment-like. Acrosanthes (6; A.

anceps, A. angustifolia, A. humifusa, A.

microphylla, A. parviflora, A. teretifolia; Western

Cape). – Acrosanthes is sister-group to

[Mesembryanthemoideae+Ruschioideae], according to Klak &

al. (2017).

Mesembryanthemoideae

Burnett, Outlines Bot.: 736, 1092, 1131. Feb 1835

[‘Mesembryanthidae’]

6/c 95. Aspazoma (1; A.

amplectens; Namaqualand and Richtersveld in Northern and Western Cape),

Brownanthus (10; southern Angola, Namibia, Northern and Western Cape),

Caulipsolon (1; C. rapaceum; Namaqualand in Northern Cape),

Mesembryanthemum

(c 70; southern Angola, Namibia, western and central South Africa to Eastern

Cape), Psilocaulon

(13; southern Angola, western Namibia, western, southern and central South

Africa), Synaptophyllum (1; S. juttae; near Lüderitz in

southwestern Namibia). – Southern Africa. CAM photosynthesis present.

Cortical vascular bundles present. Stem sometimes with succulent persistent

green cortex. Wide-band tracheids absent. Stomata usually transversely

orientated. Inflorescence indistinct. Flowers tetra- or pentamerous. Half

epigyny. Tepals, petaloid staminodia and stamens often more or less united at

base into a tube. Nectaries usually hollow or koilomorphic (shell-shaped),

discontinuous (meronectary). Pistil composed of (three or) four or five (or

six) connate carpels. Placentation axile. Expanding fruit keels entirely

septal. Alkaloids usually present.

Ruschioideae Schwantes

in Ihlenfeldt, Schwantes et Straka in Taxon 11: 54. 28 Feb 1962

106/1.410–1.430.

Apatesieae Schwantes in H. D. Ihlenfeldt, G.

Schwantes et H. Straka in Taxon 11: 55. 28 Feb 1962. Apatesia (4;

A. helianthoides, A. mughani, A. pillansii, A.

sabulosa; Vanrhynsdorp to Cape Town in Western Cape), Carpanthea

(1; C. pomeridiana; southwesternmost Western Cape), Conicosia (3;

C. bijlii, C. elongata, C. pugioniformis; southern

Namibia, Northern and Western Cape), Hymenogyne (3; H.

conica, H. glabra, H. stephensiae; Cape Peninsula to

Clanwilliam in western Western Cape), Skiatophytum (1; S.

tripolium; southwestern Western Cape). –

Dorotheantheae Chesselet, G. F. Sm. et A. E. van Wyk

in Taxon 51: 306. 12 Jun 2002. Cleretum (14;

Northern and Western Cape). – Delospermeae

Chesselet, G. F. Sm. et A. E. van Wyk in Taxon 51: 306. 12 Jun 2002.

Dicrocaulon (7–9; Namaqualand in southern Northern Cape and northern

Western Cape), Diplosoma (2; D. luckhoffii, D.

retroversum; northwestern Western Cape), Jacobsenia (3; J.

halii, J. kolbei, J. vaginata; Vanrhynsdorp and

Vredendal in Northern and Western Cape), Meyerophytum

(1; M. meyeri; Richtersveld to southern Namaqualand in Northern Cape),

Mitrophyllum (7; M. abbreviatum, M. clivorum, M.

dissitum, M. grande, M. margaretae, M.

mitratum, M. roseum; Richtersveld in Northern Cape),

Monilaria (5; M. chrysoleuca, M. moniliformis,

M. obconica, M. pisiformis, M. scutata; Namaqualand

in Northern and Western Cape), Oophytum (2;

O. nanum, O. oviforme; Knersvlakte north of Vanrhynsdorp in

Western Cape), Disphyma (6;

D. australe, D. blackii, D. clavellatum, D.

crassifolium, D. dunsdonii, D. pupillatum; Western and

Eastern Cape, southern Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand), Glottiphyllum

(16; Western and Eastern Cape); Corpuscularia (2; C.

lehmannii, C. taylorii; Port Elizabeth to Grahamstown in Eastern

Cape), Delosperma (c

160; South Africa to eastern Africa and Arabian Peninsula, Madagascar,

Réunion), Drosanthemum

(c 110; southern Namibia, western, central and southern South Africa),

Knersia (1; K. diversifolia; western Western Cape), Malephora (c

17; southern Namibia, Northern, Western and Eastern Cape), Mestoklema

(7; M. albanicum, M. arboriforme, M. copiosum,

M. elatum, M. illepidum, M. macrorhizum, M.

tuberosum; Namibia, western parts of South Africa), Trichodiadema

(34; southern Namibia, western and southern parts of South Africa),’Lampranthus’

(c 95; southern Namibia, Northern, Western and Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal;

polyphyletic), Oscularia (c

10; southern Northern Cape, Western Cape), Gibbaeum (c 18;

Little Karoo in Western Cape and southernmost Northern Cape), Muiria

(1; M. hortenseae; northern side of Langeberg in Western Cape);

Frithia (2; F. humilis, F. pulchra; northeastern

South Africa), Chasmatophyllum (6; C. braunsii, C.

maninum, C. musculinum, C. nelii, C. stanleyi,

C. willowmorense; Namibia, South Africa), Hammeria (3; H.

cedarbergensis, H. gracilis, H. meleagris; Tanqua Karoo

and Ceres Karoo in Northern and Western Cape), Rabiea (6; R.

albinota, R. albipuncta, R. comptonii, R.

difformis, R. jamesii, R. lesliei; eastern Northern

Cape, Eastern Cape, Free State), Rhinephyllum (c 10; Northern, Western

and Eastern Cape), Stomatium (40; western and southern parts of South

Africa), Mossia (1; M. intervallaris; Eastern Cape to eastern

Free State and northwestern Lesotho, Mpumalanga, Gauteng), Neohenricia

(2; N. sibbettii, N. spiculata; Northern Cape to Free State,

Eastern Cape), Faucaria (6–8; F. bosscheana, F.

britteniae, F. felina, F. gratiae, F. nemorosa,

F. subintegra, F. tigrina, F. tuberculosa; Eastern

Cape, eastern Western Cape), Orthopterum

(2; O. coeganum, O. waltoniae; Eastern Cape). –

Ruschieae Schwantes in H. D. Ihlenfeldt, G. Schwantes

et H. Straka in Taxon 11: 54. 28 Feb 1962. Aloinopsis (c 8; Western,

Eastern and Northern Cape), Deilanthe (3; D. hilmarii, D.

peersii, D. thudichumii; Western Cape and adjacent areas of

Northern and Eastern Cape, Free State), Ihlenfeldtia (2; I.

excavata, I. vanzyhlii; Northern Cape), Nananthus (5;

N. aloides, N. margaritiferus, N. pallens, N.

pole-evansii, N. vittatus; Namibia, Northern and Eastern Cape,

Free State, North-West, Gauteng), Titanopsis (3; T. calcarea,

T. hugo-schlechteri, T. schwantesii; southern Namibia,

central South Africa), Vanheerdia (2; V. primosii, V.

roodiae; Bushmanland in eastern Northern Cape), Didymaotus (1;

D. lapidiformis; Tanqua Karoo in Western Cape), Tanquana (3;

T. archeri, T. hilmarii, T. prismatica; Tanqua

Karoo, southwestern Great Karoo and Little Karoo to south of Laingsburg in

Western Cape), Dinteranthus (6; D. inexpectatus, D.

microspermus, D. pole-evansii, D. vallis-mariae, D.

vanzylii, D. wilmotianus; southeastern Namibia, northwestern

Northern Cape), Lapidaria (1; L. margaretae; southern

Namibia, northern Northern Cape), Lithops (36;

Namibia, South Africa, Botswana), Schwantesia (11; southern Namibia,

Northern Cape); Dracophilus (4; D. dealbatus, D.

delaetianus, D. montis-draconis, D. proximus; Lüderitz

in southwestern Namibia to northern Richtersveld in Northern Cape),

Hartmanthus (2; H. hallii, H. pergamentaceus;

Sperrgebiet in southern Namibia, northern Richtersveld in Northern Cape),

Jensenobotrya (1; J. lossowiana; Dolphin Head in Spencer Bay

in coastal Namibia), Juttadinteria (5; J. albata, J.

attenuata, J. ausensis, J. deserticola, J.

simpsonii; Lüderitz to Aus in Namibia, northern Richtersveld in Northern

Cape), Namibia (3; N. cinerea, N. pomonae, N.

ponderosa; around Lüderitz and east of Prince of Wales Bay in Namibia),

Nelia (4; N. meyeri, N. pillasii, N.

robusta, N. schlechteri; Richtersveld to Namaqualand in Northern

Cape), Psammophora (4; P. longifolia, P. modesta,

P. nissenii, P. saxicola; Lüderitz in western Namibia to

Richtersveld in Northern Cape), Ruschianthus (1; R. falcatus;

edge of the Namib desert in southern Namibia), Conophytum

(85–90; Northern and Western Cape to western Eastern Cape);

Bergeranthus (7–10; B. albomarginatus, B.

concavus, B. longisepalus, B. multiceps, B.

nanus, B. scapiger, B. vespertinus; Eastern Cape),

Machairophyllum (4; M. albidum, M. bijlii, M.

brevifolium, M. stayneri; Barrydale to Willowmore in Western

Cape, Zuurberg in Eastern Cape), Carruanthus

(2; C. peersii, C. ringens; around Willowmore in easternmost

Western Cape and westernmost Eastern Cape), Hereroa (c 30;

southern Namibia, South Africa), Bijlia (2; B. dilatata,

B. tugwelliae; near Prince Albert in Western Cape),

Cerochlamys (3; C. gemina, C. pachyphylla, C.

trigona; Little and Great Karoo in Western Cape); Antegibbaeum

(1; A. fissoides; Little Karoo in Western Cape), Braunsia (7;

B. apiculata, B. bina, B. edentula, B.

geminata, B. maximiliani, B. stayneri, B.

vanrensburgii; southwestern South Africa), Carpobrotus

(13; southern Africa, Australia, South America), Circandra (1; C.

serrata; at Ceres, Tulbagh and Villiersdorp in Western Cape),

Enarganthe (1; E. octonaria; Richtersveld in Northern Cape),

Erepsia (c 30; Western Cape, western Eastern Cape),

Esterhuysenia (5; E. alpina, E. drepanophylla,

E. inclaudens, E. mucronata, E. stokoei; at Caledon,

Ceres, Robertson and Worcester in Western Cape), Namaquanthus (1;

N. vanheerdii; northwest of Springbok in Northern Cape),

Scopelogena (2; S. bruynsii, S. verruculata; near

Cape Town and near Riversdale in Western Cape), Smicrostigma (1;

S. viride; north of Langeberg and Outeniqua Mountains in Western

Cape), Vlokia (2; V. ater, V. montana; near Montagu

in western Little Karoo in Western Cape), Wooleya (1; W.

farinosa; coastal parts of Namaqualand in Northern Cape),

Zeuktophyllum (2; Z. calycinum, Z. suppositum; at

Ladismith and Laingsburg in Western Cape), Octopoma (9–10; Little

Karoo in Western Cape); Acrodon (6; A. bellidiflorus, A.

deminutus, A. parvifolius, A. purpureostylus, A.

quarcicola, A. subulatus; coastal Little Karoo in Western Cape to

southwestern Eastern Cape), Arenifera (4; A. pillansii,

A. pungens, A. spinescens, A. stylosa;

Northern and Western Cape), Astridia (11; southern Namibia,

northern Northern Cape), Brianhuntleya (1; B. intrusa;

Worcester-Robertson Karroo in Western Cape), Ebracteola (6; E.

candida, E. derenbergiana, E. fulleri, E.

montis-moltkei, E. vallis-pacis, E. wilmaniae; central

Namibia, Northern Cape to central South Africa, North-West, Free State and

Gauteng), Khadia (6–8; K. acutipetala, K.

alticola, K. beswickii, K. borealis, K.

carolinensis, K. media; North-West, Gauteng, Mpumalanga and

KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa), Marlothistella (1; M.

stenophylla; Little Karoo in Western Cape), Polymita (2;

northern Namaqualand in Northern Cape), ‘Ruschia’

(220–225; Namibia, South Africa, Lesotho; non-monophyletic),

Stayneria (1; S. neilii; Breede River Valley in Western

Cape); Antimima (c 100; coastal parts of Namibia to Eastern Cape), Argyroderma

(11–12; Knersvlakte in southern Namaqualand in northwestern Western Cape),

Cephalophyllum (c 30; Namibia, Northern and Western Cape), Cheiridopsis

(23; Namibia, southwards to northern Western Cape), Cylindrophyllum

(5; C. calamiforme, C. comptonii, C. hallii, C.

obsubulatum, C. tugwelliae; Northern, Western and Eastern Cape),

Fenestraria (1; F. rhopalophylla; coastal parts of Namibia to

Richtersveld in Northern Cape), Hallianthus (1; H. planus;

Namaqualand in Northern Cape to Tanqua Karoo in Western Cape), Jordaaniella

(7; J. anemoniflora, J. clavifolia, J. cuprea,

J. dubia, J. maritima, J. spongiosa, J.

uniflora; southern Namibia, Northern and Western Cape),

Leipoldtia (8; Namibia, Northern, Western and Eastern Cape),

Octopoma (8; northern Namaqualand in Northern Cape, Little Karoo in

Western Cape), Odontophorus (4; O. angustifolius, O.

marlothii, O. nanus, O. pusillus; at Steinkopf in

Richtersveld in Northern Cape), Ottosonderia (1; O.

monticola; Namaqualand in southern Northern Cape and northern Western

Cape), Pleiospilos

(4–5; P. bolusii, P. compactus, P. leipoldtii,

P. nelii, P. simulans; Little Karoo in northern Western to

Great Karoo in western Eastern Cape), Schlechteranthus (15; northern

Namaqualand, especially Richtersveld, in Northern Cape), Vanzijlia (1;

V. annulata; coastal areas of Northern and Western Cape, Knersvlakte

in Namaqualand); Amphibolia (5; A. laevis, A.

obscura, A. rupis-arcuatae, A. saginata, A.

succulenta; coastal parts of Namibia south to southwestern Western Cape),

Eberlanzia (8; southern Namib Desert in southwestern Namibia, western

Namaqualand in Northern Cape), Ruschianthemum (1; R. gigas;

lower Orange River Valley in Namibia and Northern Cape), Stoeberia (5;

S. arborea, S. beetzii, S. carpii, S.

frutescens, S. utilis; Namaqualand in Namibia and Northern Cape),

Ectotropis (1; E. alpina; at Hogsback in the Amatola

Mountains and Katberg in Eastern Cape; in Delosperma?),

Rhombophyllum (5; R. albanense, R. dolabriforme,

R. dyeri, R. nelii, R. rhomboideum; around Uitenhage

and Port Elizabeth to Graaff-Reinet in Eastern Cape, southeastern Northern

Cape). – Southern Africa, with their largest diversity in the western coastal

part of the succulent karoo (Northern and Western Cape, Kalahari Desert etc.),

few species in eastern Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, Madagascar, Réunion and

Australia. CAM photosynthesis present. Wide-band tracheids usually frequent

(absent in basal taxa). Vesicular hairs usually absent. Leaves usually opposite

(sometimes spiral), succulent, of other form than flat (often terete or

trigonous). Inflorescence often distinct. Hypanthium usually present. Epigyny.

Tepal bases free. Nectary a koilomorphic meronectary, a wide and flat annular

holonectary, a lophomorphic (crested or lobed) holonectary, or nectary

inconspicuous or absent. Filaments usually free (sometimes connate at base),

papillate or hairy at base. Pistil composed of (three to) five to 15 (to 25)

connate carpels. Ovary inferior. Placentation basal or parietal. Fruit a

hygrochastic capsule, liberating a few seeds at a time. Expanding fruit keels

usually only on valves.

Apatesieae are sister-group to the

clade [Dorotheantheae+[Delospermeae+Ruschieae]] and

possess an annular holonectary. The capsule often lack hygrochastic properties

and has very reduced expanding keels. The clade

[Dorotheantheae+[Delospermeae+Ruschieae]] has a

covering membrane. Dorotheantheae are annual herbs with semi-succulent

leaves. The nectar is a wide and flat meronectary. The

[Delospermeae+Ruschieae] clade has a lophomorphic nectary and

a hygrochastic capsule. Moreover, the intron of the plastid gene rpoC1

is absent (lost). Delospermeae have a lophomorphic meronectary.

Ruschieae have a lophomorphic holonectary and the nuclear gene

ARP (a leaf developmental gene) is often duplicated (absent in some

species). Fruit characters are highly homoplasious. Apatesieae are

confined to the Cape Floristic Region.

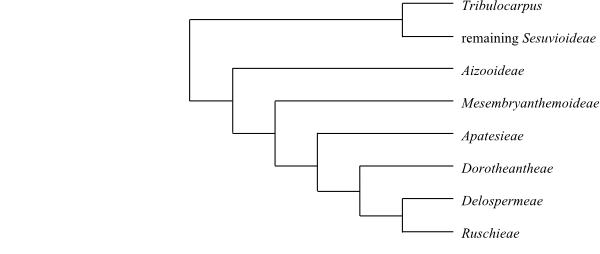

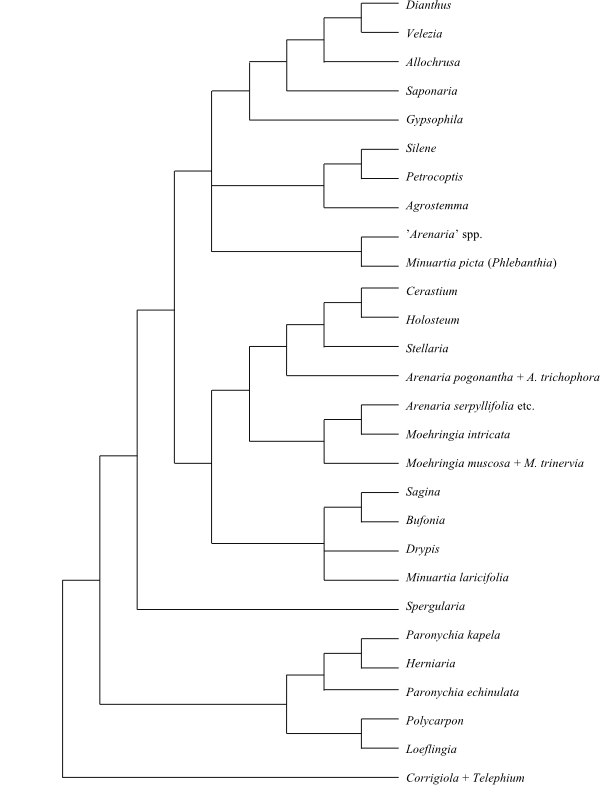

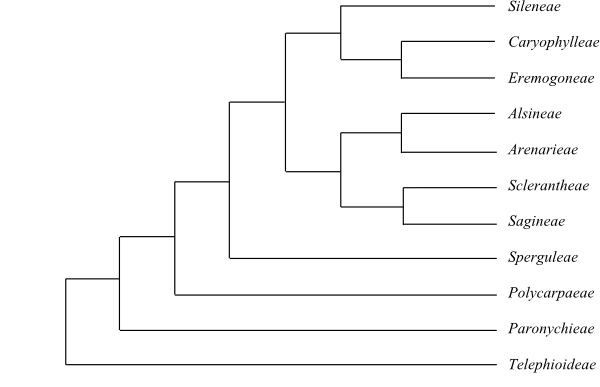

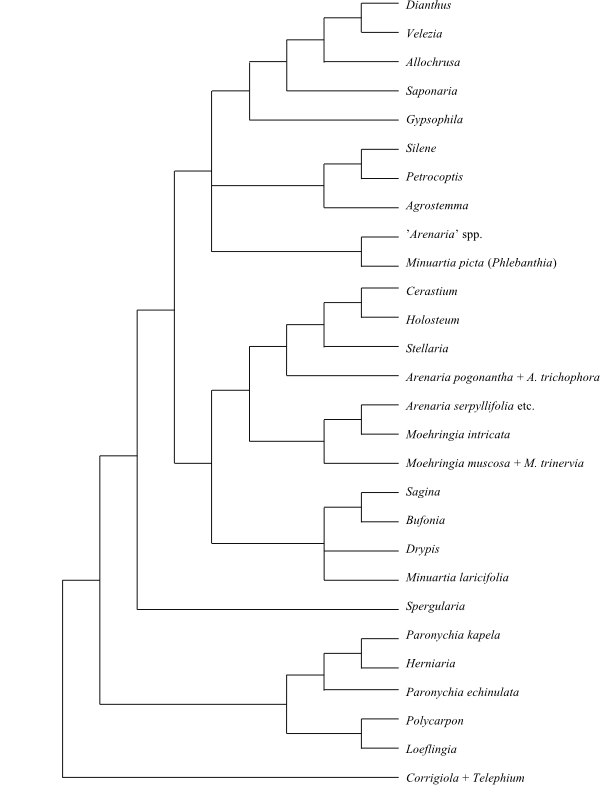

|

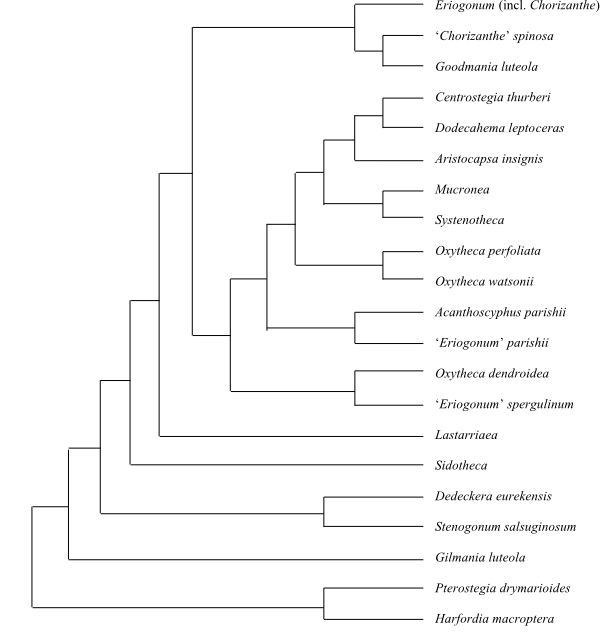

Cladogram (simplified) of Aizoaceae based on

morphology and DNA sequence data (Chesselet & al. 2002, etc.).

|

de Jussieu, Gen. Plant.: 87. 4 Aug 1789

[’Amaranthi’], nom. cons.

Atriplicaceae Juss.,

Gen. Plant.: 83. 4 Aug 1789 [’Atriplices’];

Chenopodiaceae Vent., Tabl. Règne Vég. 2: 253. 5

Mai 1799 [’Chenopodae’], nom. cons.;

Amaranthales R. Br. ex Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir.

Rostlin: 240. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Amaranthaceae’];

Celosiaceae Martinov, Tekhno-Bot. Slovar: 117. 3 Aug

1820 [’Celosiae’]; Chenopodiales Juss.

ex Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 240. Jan-Apr 1820

[‘Chenopodeae’]; Salicorniaceae

Martinov, Tekhno-Bot. Slovar: 558. 3 Aug 1820 [’Salicorniae’];

Amaranthopsida Horan., Prim. Lin. Syst. Nat.: 58. 2

Nov 1834 [’Amaranthoideae’]; Betaceae

Burnett, Outl. Bot.: 591, 1091, 1142. Feb 1835;

Achyranthaceae Raf., Fl. Tellur. 3: 35. Nov-Dec 1837

[’Achyranthidia’]; Gomphrenaceae Raf.,

Fl. Tellur. 3: 38. Nov-Dec 1837 [’Gomphrenidia’];

Polycnemaceae Menge, Cat. Plat. Grudent. Gedan.: 161.

1839 [’Polycneminae’]; Salsolaceae

Menge, Cat. Plant. Grudent. Gedan.: 165. 1839 [’Salsolinae’];

Spinaciaceae Menge, Cat. Plant. Grudent. Gedan.: 166.

1839 [’Spinacinae’]; Chenopodiineae J.

Presl in Nowočeská Bibl. [Wšobecný Rostl.] 7: 1272, 1274. 1846;

Atriplicales Horan., Char. Ess. Fam.: 63. 30 Jun 1847

[‘Atriplicastra s. Curvembryae’];

Deeringiaceae J. Agardh, Theoria Syst. Plant.: 369.

Apr-Sep 1858 [’Deeringieae’]; Blitaceae

Post et Kuntze, Lex. Gen. Phan.: 637, 710. 20-30 Nov 1903;

Dysphaniaceae (Pax) Pax in Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 61: 230.

15 Jun 1927, nom. cons.

Genera/species

176/2.000–2.075

Distribution Cosmopolitan

except polar areas, with their highest diversity in saline, arid and semiarid

areas.

Fossils Fossil pollen (e.g.

Chenopodipollis) are known from Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian),

Paleocene and Late Eocene layers in North America.

Habit Usually bisexual

(sometimes monoecious, andromonoecious, gynomonoecious, dioecious,

androdioecious, rarely polygamomonoecious), perennial, biennial or annual

herbs, evergreen or deciduous suffrutices or shrubs (rarely trees or lianas),

sometimes with spines. Often leaf or stem succulents. C4 plants with

c. 17 different types of foliar anatomy. Many species are halophytes or

xerophytes.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza

usually absent (sometimes with vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhiza). Kranz’

anatomy present in numerous species. Phellogen usually superficial or

pericyclic. Stem collenchyma well developed. Cortical and/or medullary bundles

usually present. Primary medullary strands usually wide. Endodermis usually

significant. Secondary lateral growth usually anomalous (polycyclic, anomalous

secondary vascular bundles from concentric cambia; not in

Polycnemoideae) or absent. Pericyclic fibres few or absent. Vessel

elements with simple perforation plates; lateral pits usually alternate

(sometimes opposite), simple or bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem

elements libriform fibres (with cell nuclei) with simple or (reduced) bordered

pits, non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays usually absent

(sometimes uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular). Axial

parenchyma paratracheal scanty, aliform, winged-aliform, confluent,

vasicentric, or banded. Vessel elements, fibres and/or parenchyma sometimes

partially or entirely storied. Intraxylary (concentric or diffuse) phloem

present. Sieve tube plastids P3cf type, without a central protein crystal, with

circular peripheral protein fibrils (sometimes with starch grains). Nodes 1:1

or 1:3, unilacunar with one or three leaf traces (sometimes 1:5, unilacunar

with five traces), often swollen. Heartwood sometimes with gum-like substances.

Calciumoxalate usually as crystal sand, druses or prismatic crystals (raphides

and styloids absent).

Trichomes Hair types

unicellular to multicellular, uniseriate, T-shaped or many-armed (also

malpighiaceous hairs), dendritic, stellate, candelabra-shaped, fasciculate,

lepidote, capitate and/or vesicular, often with salt-storing apical cell;

glandular hairs often present.

Leaves Alternate (spiral) or

opposite, simple, usually entire (sometimes lobed; in some stem succulents

reduced), with ? ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular

bundle transection arcuate or annular. Venation pinnate; leaves sometimes

one-veined. Stomata usually anomocytic (sometimes paracytic, diacytic or

anisocytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids as platelets (Chenopodioideae,

Salsoloideae etc.) or without platelets (Amaranthoideae etc.;

cuticular wax crystalloids absent in Dysphania). Domatia present in

many species. Hydathodes sometimes present. Leaf margin serrate, sinuate,

crenate or entire.

Inflorescence Terminal or

axillary, cymose, head-, raceme- or spike-like, thyrsoid, fasciculate or

panicle (flowers sometimes solitary, axillary). Lateral flowers of dichasial

partial inflorescences sometimes sterile and modified into scales, spines,

bristles or hairs. Bracts often membranous or coloured. Floral prophylls

(bracteoles) often petaloid (sometimes membranous). Extrafloral nectaries

rarely present (Iresine).

Flowers Actinomorphic, small.

Usually hypogyny (rarely half epigyny). Tepals (one or) three to five (to

eight), with usually imbricate (rarely valvate) aestivation, sepaloid, often

fleshy, often with tuberculate, spinulose or wing-like outgrowths, persistent,

free or connate at base, or rudimentary or absent. Nectary absent. Disc

(sometimes lobate) present in some species.

Androecium Stamens (one or)

three to five (to nine), usually as many as tepals, antetepalous, or absent.

Filaments free or connate in lower part (sometimes entirely) into a tube, often

adnate to tepals (epitepalous); tuberculate, scale-like or fringed

staminodium-like lobes, pseudostaminodia, often present between stamens and

usually fused with filaments. Anthers usually dorsifixed, often versatile,

usually tetrasporangiate (sometimes disporangiate), usually introrse (rarely

extrorse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective sometimes

with apical appendage (sometimes vesicular and coloured); anther wall

development monocotyledonous. Tapetum usually secretory, with binucleate or

multinucleate cells (sometimes amoeboid-periplasmodial). Staminodia one to

five, often petaloid, or absent.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains polypantoporate, shed as monads,

usually tricellular (rarely bicellular) at dispersal. Pollen grains often with

starch. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum,

microperforate, punctate or reticulate (in Gomphrenoideae

metareticulate), spinulate or tubuliferous.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

(one or) two or three (to six) connate carpels (median carpel sometimes

abaxial); when two carpels then usually transverse. Ovary usually superior

(rarely semi-inferior), unilocular. Style single, simple, or stylodia two or

three, long or short, more or less connate. Stigma one, capitate (simple or

penicillate), or stigmas two or three (to six), narrowly elongate, papillate,

Dry type, often persistent. Pistillodium usually absent (male flowers sometimes

with pistillodium).

Ovules Placentation usually

basal (sometimes free central or apical). Ovule usually one (ovules sometimes

few or many) per ovary, campylotropous, anacampylotropous or circinotropous

(rarely amphitropous), erect to pendulous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle

usually endostomal (rarely bistomal). Outer integument ? cell layers thick.

Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Parietal tissue? Nucellar beak present.

Apical cells of megasporangium often radially elongate. Megagametophyte usually

monosporous, Polygonum type (sometimes disporous, Allium

type). Synergids sometimes with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells usually

persistent. Chalazal caecum developed. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear.

Endosperm haustorium chalazal or absent. Embryogenesis chenopodiad or

solanad.

Fruit Usually a nut (often a

utriculus or an achene) or an irregularly dehiscent capsule (often a pyxidium,

rarely a berry, a baccaceous fruit or a drupe; adjacent ovaries sometimes

fusing and forming a syncarp), often surrounded by more or less fleshy perianth

forming an anthocarp; persistent and often accrescent bracts and floral

prophylls sometimes forming parts of dispersal unit.

Seeds Aril usually absent.

Seed coat usually exotestal-endotegmic. Outer exotestal cell walls with

stalactite-shaped appendages. Outer exotegmic cell walls often tanniniferous.

Endotegmen often thickened and lignified, tanniniferous. Perisperm usually

copious and starchy (rarely absent), usually surrounded by embryo. Endosperm

sparse or absent. Embryo curved or annular around perisperm (rarely straight;

in Salsoloideae spirally twisted), well differentiated, with or

without chlorophyll. Cotyledons usually two (rarely three). Radicula dorsal.

Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 6–36 –

Polyploidy frequently occurring.

DNA Intron absent from plastid

gene rpl2. Deletion of 300 bp in plastid IR in many clades. Plastid

genome in at least Chenopodium and Atriplex with 6 kb

inversion.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin), 6-7-methylene-dioxyflavonols, isoflavones, flavonol

sulphates, betacyanins (e.g. amaranthin, celosianin and betamin or

phyllocactin), betaxanthins, isoquinoline alkaloids and other alkaloids

(particularly in Salsoleae), triterpene saponins, cyanogenic

compounds, betaine, anthraquinones, and sterols present. Ferulic acid present

in non-lignified cell walls. Ellagic acid and proanthocyanidins not found.

Nitrate or free oxalates accumulated in many species.

Use Ornamental plants,

vegetables (Beta vulgaris, Spinacia oleracea, Chenopodium

quinoa, Atriplex hortensis, etc.), sugar (Beta vulgaris

var. altissima), forage-plants (Beta vulgaris,

Atriplex, Chenopodium, Rhagodia,

Cornulaca), glass production (Salicornia, Salsola,

etc.), timber, wood carving, medicinal plants (Dysphania etc.).

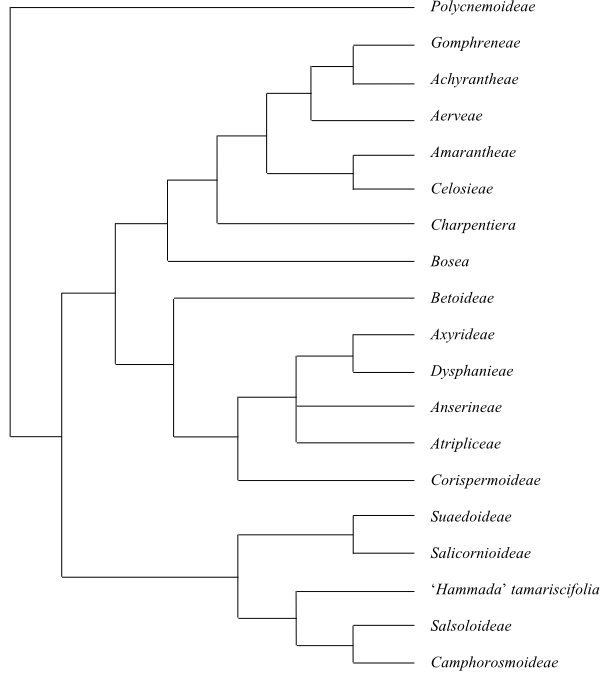

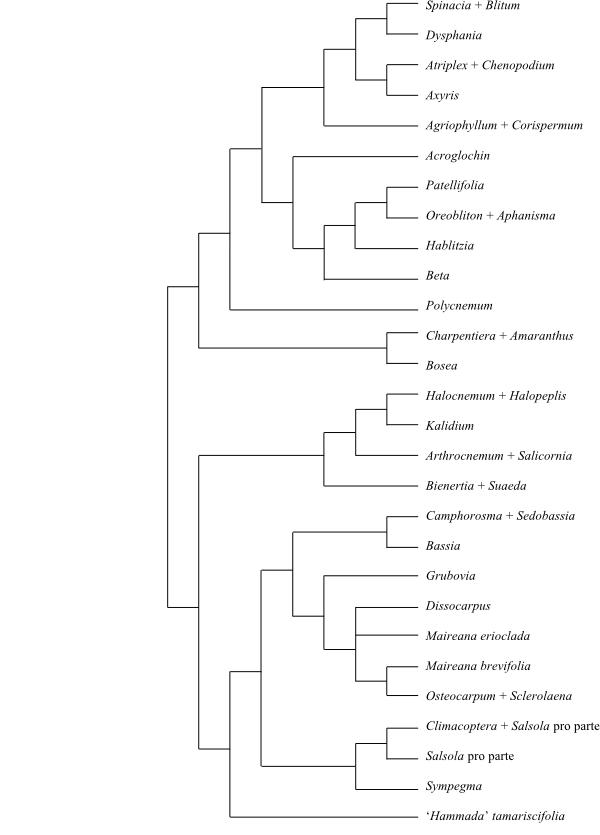

Systematics Amaranthaceae are

sister-group to Achatocarpaceae or to the

clade [Caryophyllaceae+Achatocarpaceae].

A plausible topology is, according to Kadereit

& al. (2006) and Kadereit & Freitag (2011):

[Polycnemoideae+[[Amaranthoideae+[Betoideae+[Corispermoideae+Chenopodioideae]]]+[[Suaedoideae+Salicornioideae]+[‘Hammada’tamariscifolia+[Salsoloideae+Camphorosmoideae]]]]].

Polycnemoideae Raf.,

Fl. Tellur. 3: 44. Nov-Dec 1837 [‘Polycnemides’]

4/14. Hemichroa (1; H.

pentandra; Australia, Tasmania), Surreya (2; S.

diandra, S. mesembryanthema; Australia), Nitrophila (5;

N. atacamensis, N. australis, N. mexicana, N.

mohavensis, N. occidentalis; western United States, northwestern

Mexico, Chile, Argentina), Polycnemum (6; P. arvense, P.

fontanesii, P. heuffelii, P. majus, P. perenne,

P. verrucosum; central, southern and eastern Europe, the

Mediterranean, northewesternmost Africa, Central Asia). – Europe, the

Mediterranean, Central Asia, Australia, western United States, northwestern

Mexico. Normal secondary lateral growth present. Flowers unisexual. Filaments

connate at base. Anthers in Polycnemum monothecal (disporangiate).

Pollen grains smooth or spinulose. – Polycnemoideae were sister to

all other Amaranthaceae in one

matK/trnK analysis (Müller & Borsch 2005), but nested

deeply within Amaranthaceae in analyses

by Kadereit & Freitag (2011). Polycnemum is sister to the clade

[Nitrophila+[Hemichroa+Surreya]] (Masson &

Kadereit 2013).

[[Amaranthoideae+[Betoideae+[Corispermoideae+Chenopodioideae]]]+[[Suaedoideae+Salicornioideae]+[‘Hammada’tamariscifolia+[Salsoloideae+Camphorosmoideae]]]]

[Amaranthoideae+[Betoideae+[Corispermoideae+Chenopodioideae]]]

Amaranthoideae

Burnett, Outlines Bot.: 591, 593, 1091, 1142. Feb 1835

[‘Amarantidae’] (under construction)

76/800–830. Bosea (3;

B. yervamora: the Canary Islands; B. cypria: Cyprus; B.

amherstiana: western Himalayas); Charpentiera

(6; C. densiflora, C. elliptica, C. obovata, C.

ovata, C. tomentosa: the Hawaiian Islands; C. australis:

Tubuai in the Austral Islands). – Amarantheae

Rchb., Fl. Germ. Excurs. 2(2): 575, 583. 1832. Amaranthus

(c 50; cosmopolitan), Chamissoa (2; C. acuminata, C.

altissima; warmer regions in North to South America). –

Celosieae Fenzl in S. F. L. Endlicher, Gen. Plant.:

303. Oct 1837. Celosia (c

50; warmer regions in North to South America), Deeringia (12; tropical

and subtropical regions in the Old World), Henonia (1; H.

scoparia; Madagascar), Hermbstaedtia (c 15; tropical and southern

Africa except the Cape provinces), Pleuropetalum

(3; P. pleiogynum, P. sprucei: Mexico to Peru; P.

darwinii: the Galápagos Islands). – Pleuropetalum

has racemose inflorescence, five tepals, eight stamens developed in pairs,

filaments connate at base, pistil composed of five or six connate carpels,

basal placenta with several ovules, fruit ab initio fleshy, and n = 8 or 9. –

Aerveae Fenzl in S. F. L. Endlicher, Gen. Plant.:

302. Oct 1837. Aerva (c 20;

tropical and subtropical regions in the Old World), Nothosaerva (1;

N. brachiata; tropical Africa from Senegal to Ethiopia and northern

Somalia, south to southern Africa, Mauritius, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka,

Burma, Mauritius), Ptilotus

(100–110; drier regions in Australia, one species, P. conicus, also

on Flores and Timor). – Gomphreneae Fenzl in S. F.

L. Endlicher, Gen. Plant.: 301. Oct 1837. Irenella (1; I.

chrysotricha; Ecuador), Iresine (35–40; tropical West Africa,

southern Japan, tropical and subtropical America), Woehleria (1;

W. serpyllifolia; Cuba); Alternanthera

(130–140; tropical and subtropical regions on both hemispheres, with their

largest diversity in tropical America), Pedersenia (9–10; tropical

America), Tidestromia (6; T. carnosa, T. lanuginosa,

T. rhizomatosa, T. suffruticosa, T. tenella, T.

valdesiana; southwestern United States, Mexico); Blutaparon (4;

B. portulacoides, B. rigidum [extinct], B.

vermiculare, B. wrightii; tropical West Africa, Ryukyu Islands,

tropical and subtropical America), Froelichia

(15; tropical and subtropical America, the Galápagos Islands),

Froelichiella (1; F. grisea; Brazil), ‘Gomphrena’

(130–135; tropical and subtropical regions in North to South America;

polyphyletic), Gossypianthus (2; G. lanuginosus, G.

tenuiflorus; United States, Mexico, Central America), Guilleminea

(8; Central America), Hebanthodes (1; H. peruviana; Peru),

Lecosia (2; L. formicarum, L. oppositifolia;

southeastern Brazil), Lithophila (2; L. radicata, L.

subscaposa; the Galápagos Islands), Pfaffia (c 30; tropical

South America), Pseudogomphrena (1; P. scandens; Brazil),

Pseudoplantago (2; P. bisteriliflora, P. friesii;

Venezuela, Argentina), Quaternella (3; Q. confusa, Q.

ephedroides, Q. glabratoides, Brazil), Xerosiphon (2;

X. angustiflorus, X. aphyllus; tropical South America). –