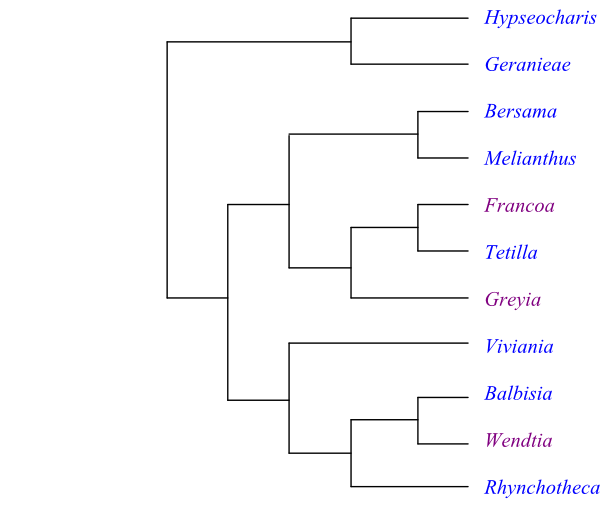

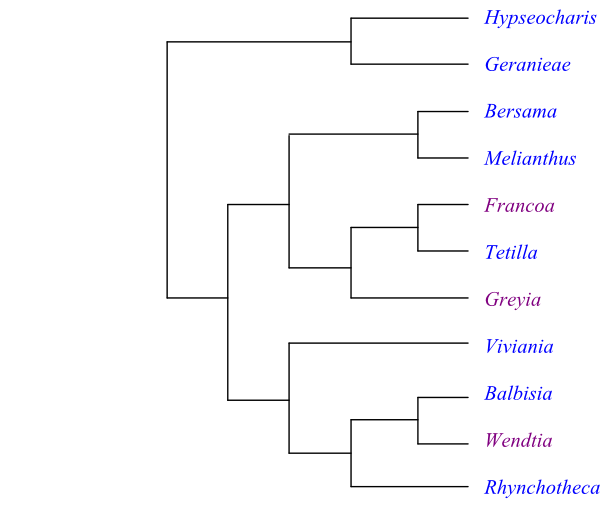

Cladogram of Geraniales based on DNA sequence data (Soltis & al. 2007).

Rosopsida Batsch, Tab. Regni Veg.: 1. 1802 [’Rosaceae’]; Hamamelididae Takht, Sist. Filog. Cvetk. Rast. [Syst. Phylog. Magnolioph.]: 461. 4 Feb 1967, pro parte; Rosidae Takht., Sist. Filog. Cvetk. Rast. [Syst. Phylog. Magnolioph.]: 264. 4 Feb 1967 pro parte; Dilleniidae Takht. ex Reveal et Takht. in Phytologia 74: 171. 25 Mar 1993, pro parte

[Fabidae+Malvidae]

(eurosids II)

[Myrtanae+Malvanae]

Myrtopsida Bartl., Ord. Nat. Plant.: 225, 326. Sep 1830 [’Myrtinae’]; Myrtidae J. H. Schaffn., Ohio Naturalist [’Myrtiflorae’] 11: 416. Dec 1911; Geranianae Thorne ex Reveal in Novon 2: 236. 13 Oct 1992

Habit Bisexual (rarely functionally polygamodioecious), evergreen or deciduous trees or shrubs, suffrutices, perennial or annual herbs (rarely trees), often xerophytic stem-succulents or geophytes, often with root- or stem-tubers.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio usually superficial (subepidermal, sometimes outer-cortical). Secondary lateral growth normal or absent (rarely anomalous). Vessel elements usually with simple (rarely reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits usually alternate (rarely scalariform). Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids or libriform fibres with simple or bordered pits, septate or non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays multiseriate, usually heterocellular (occasionally homocellular) or absent. Axial parenchyma usually paratracheal scanty or vasicentric (sometimes apotracheal diffuse), or absent. Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes usually 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces (sometimes 1:1, unilacunar with one trace, rarely 3:5, trilacunar with five traces, or 5–10:5–10, multilacunar with five to ten traces). Medullary parenchyma with starch grains. Calciumoxalate as single prismatic crystals or groups of crystals, raphides, styloids or druses.

Trichomes Hairs usually multicellular (sometimes unicellular), uniseriate, simple or branched (rarely stellate); glandular hairs simple or branched, often containing ethereal oils.

Leaves Alternate (spiral) or opposite (rarely verticillate), simple or compound, entire or lobed, with conduplicate to plicate ptyxis. Stipules intrapetiolar or interpetiolar (rarely pairwise and lateral, or absent); leaf sheath usually absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection annular. Venation pinnate or palmate, usually brochidodromous or craspedodromous (rarely actinodromous). Stomata usually anomocytic (sometimes paracytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids usually absent (sometimes as rodlets or platelets). Leaflets and lobes usually serrate (sometimes glandular serrate), crenate or sinuate (sometimes entire).

Inflorescence Terminal, axillary or leaf-opposite, corymbose, thyrse, cymose umbel-like or few-flowered (rarely raceme or panicle), or flowers solitary axillary. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) sometimes absent.

Flowers Actinomorphic or zygomorphic. Hypanthium present or absent. Usually hypogyny (rarely half epigyny). Sepals (four or) five, with imbricate (often apically valvate, rarely induplicate-valvate) aestivation, free or connate at base. Petals (two to) five (or six; rarely absent), usually with imbricate (sometimes contorted) aestivation, usually clawed, caducous, free. Nectaries (nectariferous glands) five, antesepalous, alternipetalous, alternating with stamens (nectariferous disc rarely lobate, annular, extrastaminal). Disc extrastaminal (sometimes absent).

Androecium Stamens usually five or 5+5 (rarely four or 4+4, 10+5, or 5+5+5), obdiplostemonous. Filaments usually connate at base (sometimes free), free from tepals. Anthers usually dorsifixed (sometimes basifixed), usually versatile, tetrasporangiate, usually introrse (rarely extrorse or latrorse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory or amoeboid-periplasmodial. Staminodia usually absent (sometimes five, extrastaminal, or three to eight, rarely ten, extrastaminal and alternating with stamens).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis usually simultaneous (rarely successive). Pollen grains (2–)3(–15)-colpate, (2–)3(–15)-colporate or inaperturate (rarely polypantoporate), shed as monads, bicellular or tricellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, reticulate, reticulate-striate, or striate, gemmate, echinate or with other types of supratectal processes.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (two to) five (to seven) antepetalous connate carpels. Ovary usually superior (rarely semi-inferior), (bilocular to) quinquelocular, (bilobate to) quinquelobate. Stylodia (four or) five (style sometimes single, simple, or absent). Stigmas (two to) five (sometimes one, capitate or tri- or quinquelobate), punctate to slightly widened, usually papillate (rarely non-papillate), usually Dry (sometimes Wet) type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation usually axile (sometimes marginal, rarely apical, basal or intrusively parietal). Ovules usually one or two (rarely up to twelve, only one of which is developing, or up to c. 50) per carpel, usually anatropous to campylotropous by insertion of inner integument (rarely hemianatropous), ascending, pendulous or ascending, usually epitropous, bitegmic (outer integument sometimes mostly epidermal in origin), crassinucellar. Micropyle usually bistomal (sometimes endostomal), often Z-shaped (zig-zag). Nucellar cap usually absent (rarely present). Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis onagrad or asterad.

Fruit Usually a schizocarp with (four or) five single-seeded (rarely follicular) mericarps (rarely a loculicidal, septicidal or septifragal capsule).

Seeds Aril usually absent. Seed coat usually testal-exotegmic (rarely exotestal). Exotesta usually unspecialized (rarely palisade). Endotesta palisade, consisting of malpighian-like cells with calciumoxalate crystals and thickened unlignified cell walls. Exotegmen usually palisade, with sinuous, anticlinal and poorly lignified cell walls. Endotegmen sometimes with slightly lignified cell walls. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm usually absent (sometimes sparse, rarely copious), oily. Embryo straight to curved (rarely spirally twisted), oily, well differentiated, usually with chlorophyll. Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology x = 4, 7–15

DNA Plastid gene infA lost/defunct. Mitochondrial intron coxII.i3 lost.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), flavone-C-glycosides, desoxyflavonoids with B-ring, monoterpenoids (citronellol, geraniol) and their esters (citronellyl, geraniyl [pelargonium-oil]), oleanolic acid derivatives, ellagic and gallic acids, ellagitannins (e.g. geraniins), alkaloids, toxic bufadienolides, and tartaric acid present. Non-hydrolyzable tannins, proanthocyanidins, and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Systematics Geraniales are sister-group to Myrtales.

A probable topology of Geraniales is [Geraniaceae+[Ledocarpaceae+[Melianthaceae+ Francoaceae]]].

Melianthaceae and Francoaceae share the following potential synapomorphies (Stevens 2001 onwards): leaves spiral, with fairly broad insertion and conduplicate ptyxis; inflorescence terminal, racemose, with sterile bract(s) at apex; absence of floral prophylls (bracteoles); carpels lobate; long style; placentae intrusive; ovules in two rows; micropyle bistomal; endosperm copious; embryo short; and presence of inulin.

|

Cladogram of Geraniales based on DNA sequence data (Soltis & al. 2007). |

FRANCOACEAE A. Juss. |

( Back to Geraniales ) |

Francoales A. de Jussieu in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp. Regn. Veg.: 48. Sep-Oct 1835 [‘Francoaceae’]; Greyiaceae Hutch., Fam. Fl. Pl. 1: 202. 15 Jan 1926, nom. cons.; Greyiales Takht., Divers. Classif. Fl. Pl.: 265. 24 Apr 1997

Genera/species 3/5

Distribution South Africa, Chile.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Usually bisexual, evergreen or deciduous trees or shrubs (Greyia) or rhizomatous perennial herbs (Francoa, Tetilla).

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio subepidermal to cortical. Young stem in Francoa and Tetilla with pseudosiphonostele. Cortical or medullary vascular bundles sometimes present. Primary medullary rays wide. Secondary lateral growth normal (Greyia), anomalous or absent. Vessel elements with simple perforation plates; lateral pits alternate to scalariform, bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform fibres (sometimes tracheids?) with simple or bordered pits, non-septate. Wood rays multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma usually paratracheal scanty or vasicentric (in Greyia also with few diffusely dispersed cells). Cambium and wood elements usually storied (tall wood rays not storied). Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes 3:5, trilacunar with five leaf traces (Francoa, Tetilla), or 9:9, novemlacunar with nine traces (Greyia). Calciumoxalate as raphides, druses, styloids or single prismatic crystals; raphides present in xylem in Greyia.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate (sometimes multi-armed); glandular hairs densely spaced in Francoa and Tetilla.

Leaves Alternate (spiral), pinnately compound or simple and pinnately lobed, with conduplicate-plicate ptyxis. Stipules usually absent (rarely present in Greyia); leaf sheath present in Francoa and Greyia; widened leaf bases in Greyia fused with stem and forming pseudocortex. Petiole vascular bundle transection usually annular. Venation palmate or pinnate, actinodromous or craspedodromous (Francoa). Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids as irregularly orientated platelets, or cuticular waxes absent. Mesophyll with calciumoxalate as raphides (often in idioblasts), druses, styloids or solitary prismatic crystals. Leaf margin usually serrate (rarely entire); hydathodes present in leaf teeth in Greyia.

Inflorescence Usually terminal or lateral (rarely axillary), raceme or panicle. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) absent.

Flowers Actinomorphic or zygomorphic, in Greyia resupinate. Hypogyny or half epigyny. Sepals four or five (Francoa, Tetilla) or (four or) five (Greyia), with contorted to imbricate (or induplicate-valvate?; in Greyia imbricate) aestivation, more or less free, or three sepals free and two connate, without spur; sepals in Greyia persistent. Petals (three or) four or five (or six), usually with imbricate-ascending aestivation, clawed or sessile, unequally sized, recurved, caducous (Greyia), free. Nectariferous disc extrastaminal, large, annular, often lobate (in Greyia decemlobate, corona-like, with ten interstaminal ridges adnate to ovary).

Androecium Stamens in Francoa and Tetilla usually eight (sometimes four), in Greyia (eight or) ten, in one whorl, obdiplostemonous (Francoa, Greyia) or diplostemonous (Tetilla). Filaments usually free (in, e.g., Francoa connate at base), free from tepals. Anthers basifixed, often versatile, tetrasporangiate, latrorse to introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory, with uninucleate or multinucleate (Francoa) cells. Staminodia in Tetilla four, in Francoa eight, alternating with stamens (lobes of nectariferous disc with ten gland-like extrastaminal staminodia alternating with stamens).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous or successive. Pollen grains tricolporate (Greyia, Francoa) with complex endoapertures, shed as monads, usually bicellular (rarely tricellular) at dispersal. Exine semitectate, with columellate? infratectum, reticulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (three or) four (Francoa, Tetilla) or (four or) five (to seven; Greyia) connate carpels. Ovary superior or semi-inferior, usually quadrilocular or quinquelocular, often deeply lobed (in Greyia unilocular, with carpels paracarp connate, or quinquelocular with free carpels except common central part). Style single, simple, short (Greyia) or absent (Francoa, Tetilla). Stigma entire, punctate or somewhat expanded and ridged (in Greyia quinquelobate; in Francoa and Tetilla commissural, usually with two lobes each composed of two carpels), non-papillate (Greyia), Wet type. Pistillodium?

Ovules Placentation axile to apical, with intrusive placentae (in Greyia intrusively parietal, when ovary unilocular). Ovules c. 20 to c. 50 per carpel, anatropous, pendulous, horizontal or ascending, apotropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle bistomal. Outer integument ? layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Funicular obturator present in Francoa and Tetilla. Parietal tissue approx. five cell layers thick. Nucellar cap? Hypostase present. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type, elongated. Suspensor present in Greyia. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear (Francoa). Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis in Greyia asterad.

Fruit A septicidal capsule (Francoa, Tetilla); in Greyia a schizocarp with five ventricidal follicular mericarps.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat exotestal (Francoa, Tetilla) or testal-tegmic (Greyia). Testa multiplicative. Exotesta palisade; exotestal cells crystalliferous, elongate, with thickened outer walls. Mesotestal and endotestal cells thin-walled, with calciumoxalate as styloids and other crystal types; endotestal cells in Greyia with thickened and lignified radial walls, in Francoa and Tetilla elongate, with thickened anticlinal walls. Tegmen in Greyia fibrous; in Francoa and Tetilla consisting of pigmented cells. Mesotegmic cells elongate. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, oily and sometimes starchy, thick-walled (Greyia). Embryo minute, straight, well differentiated, with chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, narrow. Radicula with anthocyanin (Francoa). Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 26 (Francoa), 16, 17 (Greyia)

DNA

Phytochemistry Deoxyflavonoids with B-ring (Greyia), anthocyanins (in roots), oleanolic acid derivatives, and inulin? present. Flavonols, ellagic acid, proanthocyanidins, saponins, cyanogenic compounds, rutinosides, and cyanolipids not found.

Use Ornamental plants, medicinal plants, timber, carpentries.

Systematics Greyia (3; G. flanaganii, G. radlkoferi, G. sutherlandii; Northern Province, Mpumalanga, KwaZulu-Natal, Eastern Cape, with their largest diversity in eastern Transvaal and Drakensberg); Francoa (1; F. appendiculata; mountains in central Chile), Tetilla (1; T. hydrocotylifolia; mountains in central Chile).

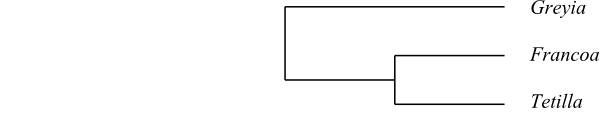

Francoaceae are sister-group to Melianthaceae.

|

Cladogram of Francoaceae based on DNA sequence data and morphology. |

GERANIACEAE Juss. |

( Back to Geraniales ) |

Geraniopsida Meisn., Plant. Vasc. Gen.: Tab. Diagn.: 57, Comm.: 41. 21-27 Mai 1837; Erodiaceae Horan., Char. Ess. Fam.: 192. 30 Jun 1847; Hypseocharitaceae Wedd., Chlor. Andina 2: 288. Nov 1861 [’Hypseocharideae’]; Geraniineae Bessey in C. K. Adams, Johnson’s Universal Cyclop. 8: 461. 15 Nov 1895

Genera/species 6/835–840

Distribution Cosmopolitan except polar areas, especially in temperate and subtropical regions, with their largest diversity in South Africa; few species in tropical regions.

Fossils Fossil pollen grains of Geranium and Pelargonium are known from the Miocene of Spain, and of Pelargonium from the Pliocene of southeastern Australia.

Habit Bisexual, usually perennial or annual herbs (sometimes suffrutices or shrubs; in Geranium section Neurophyllodes trees), some species are xerophytic stem succulents and a large number are geophytes, often with root or stem tubers.

Vegetative anatomy Roots usually diarch (sometimes triarch). Phellogen ab initio usually superficial (in Pelargonium section Hoarea within outermost cortical parenchyma; in Monsonia section Sarcocaulon thick waxy bark, ’bushmen candle’, formed from periderm). Endodermis sometimes significant. Secondary lateral growth normal or absent. Vessel elements usually with simple (rarely reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits usually alternate. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform fibres with simple pits, often septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays usually heterocellular (often absent). Axial parenchyma usually paratracheal scanty (sometimes apotracheal diffuse). Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces. Medullary parenchyma with starch grains. Groups of calciumoxalate crystals abundant.

Trichomes Hairs multicellular, simple; glandular hairs containing ethereal oils often frequent, especially on leaves.

Leaves Usually alternate (spiral; sometimes opposite, especially lower ones), often in basal rosette, simple, pinnately or palmately compound, entire or lobed, with conduplicate-plicate ptyxis. Stipules intrapetiolar or interpetiolar (rarely modified into spines; absent in Hypseocharis); leaf sheath absent. Petiolules not articulated. Petiole vascular bundle transection annular. Venation palmate or pinnate. Stomata usually anomocytic (sometimes paracytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids usually absent (rarely as rodlets). Leaflets and lobes usually serrate, crenate or sinuate (sometimes entire).

Inflorescence Terminal, axillary or leaf-opposite, umbel-like cymose, two-flowered cymes in compound cymose partial inflorescences (often pseudo-umbellate; in Geranium geranioid inflorescence, according to Schroeder 1987; multiple thyrse, according to Endress 2010), or flowers solitary axillary (in Monsonia section Sarcocaulon).

Flowers Actinomorphic or zygomorphic. Hypanthium present (Pelargonium) or absent. Hypogyny. Sepals (four or) five, with imbricate (often quincuncial; apically valvate) aestivation, persistent in fruit, aristate, free or connate at base (in Pelargonium adaxial sepal often prolonged into tube); sepal layer with small hypodermal druse-containing cells often present. Petals usually five (rarely two, four or absent), usually with imbricate (sometimes contorted?) aestivation, clawed, caducous, free. Nectaries five, antesepalous, alternipetalous, vascularized, alternating with stamens; nectary in Pelargonium usually deeply sunken into hypanthium; nectaries in Monsonia often in axils of sepals or abaxially on staminal bases (nectariferous disc in Hypseocharis lobate, annular, extrastaminal). Disc usually present.

Androecium Stamens usually five or 5+5 (rarely two, four, seven or 4+4; in Monsonia usually 10+5 [outer ten stamens antepetalous and pairwise, inner five stamens antesepalous], in Hypseocharis usually 5+5+5 [rarely five antepetalous]; when 15, then sometimes five fascicles of three connate stamens), obdiplostemonous or antepetalous. Filaments usually connate at base (sometimes free), free from tepals. Anthers dorsifixed, usually versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory or amoeboid-periplasmodial. Staminodia usually absent; in Erodium five, extrastaminal; in Pelargonium three to eight; in one species of Monsonia ten, extrastaminal and alternating with stamens.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains (2–)3(–15)-colpate (Hypseocharis?, Monsonia) or (2–)3(–15)-colporate (Geranium, Erodium, Pelargonium, Hypseocharis?) or inaperturate, shed as monads, bicellular or tricellular at dispersal; sometimes starchy. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, striate (often with interwoven striate elements), reticulate, reticulate-striate or reticulate and beset with gemmae or other supratectal processes.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (four or) five connate carpels, usually prolonged into beak in fruit. Ovary superior, (quadrilocular or) quinquelocular, (quadrilobate or) quinquelobate (in Hypseocharis with gynophore). Stylodia (four or) five (in Hypseocharis one, narrow, simple). Stigmas (four or) five (in Hypseocharis one, capitate), papillate, Dry type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation axile(-marginal). Ovules usually one or two (rarely up to twelve, only one of which developing; in Hypseocharis c. 20 to more than 50) per carpel, usually anatropous to campylotropous by invagination of inner integument due to cell development (sometimes hemianatropous), ascending or pendulous, usually epitropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle bistomal (Hypseocharis), Z-shaped (zig-zag) or endostomal (rarely exostomal). Outer integument two or three cell layers thick. Inner integument two or three cell layers thick. Hypostase present in Hypseocharis. Parietal tissue approx. four cell layers thick. Nucellar cap usually absent. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development usually nuclear (in Hypseocharis later cellular). Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis onagrad or asterad.

Fruit Usually a capsule-like schizocarp with (four or) five one-seeded mericarps; one mericarp and one usually hygroscopic stylar segment dehiscing elastically and acropetally from common central rostrum (central column developed from ovary septa), seeds often thrown out (some species of Hypseocharis with five one- or few-seeded mericarps not connate via central column; in other species of Hypseocharis loculicidal capsule).

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat endotestal-exotegmic. Exotesta unspecialized. Endotesta palisade, consisting of malpighian-like cells with calciumoxalate crystals and heavily thickened unlignified cell walls. Exotegmen palisade, with poorly lignified sinuous anticlinal cell walls. Endotegmen sometimes with slightly lignified cell walls. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm usually absent (sometimes sparse). Embryo straight to curved (in Hypseocharis coiled), oily, well differentiated, with chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, folded. Radicula dorsal. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology x = 4, 7–15 – Polyploidy frequently occurring (up to 12x).

DNA Plastid genome extensively rearranged in Geraniaceae. Examples as follows. Plastid gene rpl16 intron lost. Plastid gene infA lost/defunct (Erodium, Pelargonium). Plastid gene rpl2 intron lost in Monsonia (incl. Section Sarcocaulon). Plastid gene accD and ORF2280 absent in numerous species. Plastid gene clpP absent in at least two species of Geranium and in Monsonia (incl. section Sarcocaulon). Plastid gene rpoA absent in Pelargonium, and rpl20 from Monsonia section Sarcocaulon. Group II intron between mitochondrial gene nad1 b and c exons absent. In Pelargonium x hortorum the plastid inverted repeat has expanded by 76 kb. Ribosomal protein and succinate dehydrogenase genes transferred from mitochondrial genome to nuclear genome (Erodium). Plastid inverted repeat absent in Erodium and Monsonia section Sarcocaulon. Plastid genome in Erodium chamaedryoides with one or two inversions, in Geranium grandiflorum (?) several inversions, in Pelargonium x hortorum approx. six inversions, and in Monsonia section Sarcocaulon several inversions.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), flavone-C-glycosides, ellagic and gallic acids, hydrolyzable tannins (ellagitannins, e.g. geraniins), alkaloids, petroselinic acid, and vernolic acid (Geranium) present; in many species of Pelargonium also the monoterpenoids citronellol, geraniol and their esters citronellyl och geraniyl (pelargonium-oil), and tartric acid. Proanthocyanidins and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Ornamental plants, perfumes, flavours and aromatic additives (Pelargonium).

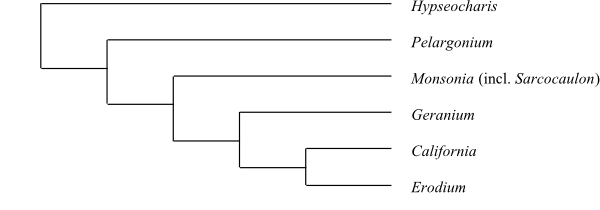

Systematics Geraniaceae are sister-group to the remaining Geraniales.

Hypseocharis is sister to the remaining Geraniaceae.

Hypseocharis

1/8. Hypseocharis (8; H. bilobata, H. fiebrigii, H. malpasensis, H. moschata, H. pedicularifolia, H. pilgeri, H. pimpinellifolia, H. tridentata; the Andes in Chile and Argentina). – Perennial acaulescent or almost stemless herbs with tuber or thick taproot. Stipules absent. Nectariferous disc lobate, annular, extrastaminal. Stamens usually 5+5+5, with ten stamens in antepetalous pairs (rarely five antepetalous). Gynophore present. Style single, simple, filiform. Stigma capitate. Ovules approx. c. 20 to more than 50 per carpel. Micropyle bistomal, Z-shaped (zig-zag). Hypostase present. Endosperm development later cellular. Fruit in some species with five one- or few-seeded mericarps not connate via central column, in other species a loculicidal (in H. tridentata septicidal-ventricidal) capsule with persistent filaments. Endosperm sparce. Embryo coiled. Cotyledons alternate. n = ? – Hypseocharis is sister to all other Geraniaceae. – Hypseocharis tridentata seems to be sister to the remaining species of Hypseocharis.

Geranieae Sweet, Geraniaceae 1: vii. 1820

5/c 830. Pelargonium (c 250; Africa, Madagascar, Asia, St. Helena [P. cotyledonis], Tristan da Cunha, Australia, New Zealand, with their highest diversity in the Cape Provinces in South Africa), Monsonia (c 40; Africa, Madagascar, southwestern Asia, with their highest diversity in southern Africa), Geranium (c 415; temperate regions on both hemispheres, tropical mountains, the Hawaiian Islands), Erodium (c 125; Europe, the Mediterranean to Central Asia, southern Australia, southern tropical South America), California (1; C. macrophylla; southern Oregon, California, Baja California in northwestern Mexico). – Subcosmopolitan. Usually annual or perennial herbs (often geophytes; sometimes stem succulents; rarely shrubs). Stem often articulated. Phellogen epidermal. Vessel elements usually with simple (rarely scalariform) perforation plates. Wood rays often absent. Nodes 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf-traces. Glandular hairs often frequent. Leaves usually alternate (sometimes opposite), simple, pinnately or palmately compound, entire or lobed, with conduplicate-plicate ptyxis. Stipules paired, often well developed, interpetiolar or cauline. Colleters present. Petiole vascular bundle transection annular; medullary bundles sometimes present. Cuticular wax crystalloids usually absent (rarely as rodlets). Flowers actinomorphic or zygomorphic (especially in Pelargonium). Sepals often with nectariferous spur (sometimes adaxial spur adjacent to pedicel; in Pelargonium nectary in pedicel; nectary in Monsonia antepetalous), aristate. Petals (four or) five (sometimes fimbriate). Stamens usually 5, 10 or 15 (in Pelargonium two to five or seven, antepetalous staminal whorl staminodial). Filaments often connate at base. Pollen grains rarely colpate, often large, tricellular at dispersal. Pistil composed of (two to) five connate carpels. Style usually short, stout, hollow. Stigma lobate. Placentation apical. Ovules usually one or two per carpel. Micropyle usually endostomal (rarely exostomal). Megagametophyte invading and obliterating apical part of megasporangial tissue. Fruit a capsule-like septicidal schizocarp, with upper ovary part prolonged; mericarps twisting upwards, separating from columella. Exotestal cells stellate in outline, indistinctly delimited. Endotegmic cells walls sometimes slightly lignified. Endosperm absent. Embryo curved, usually with chlorophyll. Cotyledons longitudinally plicate or accumbent. Radicula long. n = 4, 7–11, 14, 15 or higher. Sporophytic incompatibility often occurring.

|

Cladogram (simplified) of Geraniaceae based on DNA sequence data (Fiz & al. 2008). |

LEDOCARPACEAE E. Mey. |

( Back to Geraniales ) |

Vivianiaceae Klotzsch in Linnaea 10: 433. Mai 1836, nom. cons. prop.; Rhynchothecaceae (Endl.) A. Juss. in V. V. D. d’Orbigny, Dict. Univ. Hist. Nat. 11: 131. 9 Sep 1848 [’Rhyncotheceae’]; Ledocarpales Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.: xxxvii. 23 Dec 2001

Genera/species 4/22

Distribution Western South America, with their highest diversity in the Andes.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, evergreen or deciduous shrubs or suffrutices (sometimes perennial or annual herbs). In Rhynchotheca and some species of Viviania many short shoots are modified into spines.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen? Cork cells with tannins. Medulla parenchymatous or sclerenchymatous. Cortex parenchymatous (without sclerenchyma). Vessel elements with simple perforation plates (in Viviania sometimes with rib crossing perforation); lateral pits circular or elliptic. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids with simple (Balbisia) or bordered (Viviania) pits. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma paratracheal or absent. Wood elements often storied; cambium in Viviania storied. Tyloses spherical or absent. Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes in Viviania 1:1, unilacunar with one leaf trace. Calciumoxalate druses present.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular, simple or branched; glandular hairs uniseriate, simple or branched.

Leaves Usually opposite or almost opposite (rarely verticillate), simple or compound (pinnately compound or trifoliolate), entire or pinnately lobed, with ? ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent (petiole bases united by transverse line across stem/branch). Petiole vascular bundle transection? Venation pinnate to subpalmate (Viviania), brochidodromous or craspedodromous. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids as platelets (in Viviania band-shaped) or absent. Leaf margin serrate or entire.

Inflorescence Terminal, corymb-like (thyrse with monochasial to asymmetrical dichasial paraclades, often reduced to two or three flowers), or flowers solitary; inflorescence in Viviania sometimes entirely or partially modified into branched spine.

Flowers Actinomorphic. Hypogyny. Epicalyx consisting of bracts present or absent. Sepals four or five, with imbricate (apically valvate) aestivation, persistent in fruit, free or connate at base (in Viviania; sepals in Viviania with eight or ten distinct ridges), often aristate. Calyx layer with small hypodermal druse-containing cells present in Viviania. Petals usually four or five (absent in Rhynchotheca), with contorted or imbricate aestivation, free. Nectary absent or nectariferous glands alternipetalous, rarely bilobate (Viviania). Disc extrastaminal, consisting of separate alternipetalous units (absent in Balbisia).

Androecium Stamens usually five long and five short (in Viviania rarely four, five, eight or 5+5+5), usually obdiplostemonous. Filaments often widened at base and connate into ring (in Viviania often with pair of basal appendages, probably nectaries), free from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse or extrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory? Staminodia absent or as (four or) five nectariferous glands.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous? Pollen grains inaperturate (Balbisia, Wendtia) or 21–60-pantoporate (Rhynchotheca, Viviania), shed as monads, bicellular? at dispersal. Exine usually semitectate (in some species of Viviania pertectate), with columellate infratectum, usually reticulate, often finely echinate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of two, three or five connate antesepalous carpels; odd carpel in Viviania abaxial. Ovary superior, bilocular, trilocular or quinquelocular and bilobate, trilobate or quinquelobate. Style single, short, or absent. Stigma single, trilobate or quinquelobate, with revolute margins, or two or three; stigmatic areas adaxial, usually Dry type (in Rhynchotheca Wet type and mucilaginous). Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation usually axile (rarely apical). Ovules usually one or two to twenty, collateral or superposed (rarely more than twenty; in Viviania two, superposed) per carpel, anatropous (Rhynchotheca), twisted and campylotropous (Viviania) or hemianatropous to campylotropous (Balbisia), ascending or pendulous, epitropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal. Outer integument two or three cell layers thick. Inner integument two or three cell layers thick. Integument more or less thickened near micropyle. Obturator hairy at funicle. Nucellar cap present. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit Usually a loculicidal and sometimes septifragal (Balbisia, Rhynchotheca) or septicidal (Rhynchotheca, Viviania) acute capsule (in Rhynchotheca with columella).

Seeds Aril absent. Funicle hairy. Testa four- or five-layered (in Viviania sometimes hairy). Raphe in Viviania tanniniferous. Exotesta inBalbisia often with mucilaginous or tanniniferous cells (some representatives of Rhynchotheca and Viviania with thick-walled, narrowly elongate, non-lignified exotegmic cells). Endotesta? Exotegmic cells in Viviania sometimes thick-walled, elongate, unlignified. Endotegmen tanniniferous. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm sparse (in Rhynchotheca thin-walled) or copious and starchy (some species of Viviania), oily, with thick and pitted cell walls. Embryo straight (Rhynchotheca), cordate or spirally twisted (Viviania, in some species with long suspensor), or strongly twisted (Balbisia), well differentiated, sometimes with chlorophyll (Viviania). Cotyledons one? (Viviania, Rhynchotheca) or two (Balbisia). Germination?

Cytology x = 7 (Viviania), 9 (Balbisia, Rhynchotheca)

DNA

Phytochemistry Very insufficiently known. Anthocyanins and ellagitannins present.

Use Unknown.

Systematics Viviania (9; V. albiflora, V. crenata, V. elegans, V. guevarana, V. marifolia, V. montevidensis, V. ovata, V. parviflorum, V. tenuicaulis; southern Brazil, Uruguay, Chile, northern and western Argentina, with their largest diversity in the Andes); Rhynchotheca (1; R. spinosa; the Andes in Chile and Argentina), Balbisia (11; the Andes of Peru, Bolivia, northern Chile and northwestern Argentina), Wendtia (1; W. gracilis; Chile, western Argentina).

Vivianiaceae are sister to Ledocarpaceae.

Balbisia is sister to Wendtia. Both Balbisia and Wendtia have inaperturate pollen grains.

MELIANTHACEAE Horan. |

( Back to Geraniales ) |

Melianthales Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 220. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Meliantheae’]; Bersamaceae Doweld in Plant Syst. Evol. 227: 83. 7 Mai 2001

Genera/species 2/14

Distribution Tropical and southern Africa.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Usually bisexual (in Bersama functionally polygamodioecious), evergreen or deciduous small trees or shrubs (Bersama) or suffrutices (Melianthus).

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio subepidermal to cortical. Cortical or (phloic) medullary vascular bundles sometimes present. Primary medullary rays wide. Secondary lateral growth anomalous or absent. Vessel elements with simple perforation plates; lateral pits alternate to scalariform, bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform fibres (sometimes tracheids?) with simple or bordered pits, non-septate. Wood rays multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma usually paratracheal scanty or vasicentric. Cambium and wood elements usually storied (tall wood rays not storied). Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes 5–10:5–10, multilacunar with five to ten leaf traces. Calciumoxalate as raphides, druses, styloids or single prismatic crystals.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate or multiseriate, simple or branched (sometimes multi-armed, sometimes stellate); glandular hairs often present.

Leaves Alternate (spiral), imparipinnate (leaflets entire, articulated), with conduplicate-plicate ptyxis. Stipules paired and usually lateral, cauline, persistent (Melianthus), or single intrapetiolar and caducous (Bersama); leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection usually annular; petiole sometimes with cortical or medullary vascular bundles. Venation palmate or pinnate, actinodromous. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids as irregularly orientated platelets, or cuticular waxes absent. Mesophyll with calciumoxalate as raphides (often in idioblasts), druses or styloids (sometimes solitary prismatic crystals). Leaf margin usually serrate (rarely entire); hydathodes present in leaf teeth in at least Bersama.

Inflorescence Usually terminal (rarely axillary), raceme or panicle. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) absent.

Flowers Zygomorphic (in Bersama with zygomorphic calyx), resupinate (in Melianthus with significant mentum consisting of adaxially widened receptacle). Hypogyny or half epigyny. Sepals (four or) five (in Melianthus two showy adaxial sepals arched at least above androecium and gynoecium), with induplicate to valvate aestivation, more or less free, or three sepals free and two connate, adaxial sepal with (Melianthus) or without spur. Petals (three or) four or five (or six), with imbricate-ascending (contorted?) or valvate (Bersama) aestivation, clawed or sessile, unequally sized, recurved, free (in Melianthus densely connivent via crystalline hairs). Nectary adaxial, extrastaminal, large, annular (nectariferous disc; Bersama) or unilateral, often lobed.

Androecium Stamens four, haplostemonous, antesepalous, alternipetalous, without adaxial stamens. Filaments free from each other and from tepals. Anthers usually basifixed (in Bersama dorsifixed), often versatile, tetrasporangiate, latrorse to introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory, with uninucleate or multinucleate cells. Staminodia?

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous or successive. Pollen grains dicolporate or tricolporate (Melianthus), shed as monads, usually bicellular (rarely tricellular) at dispersal. Exine semitectate, with columellate? infratectum, reticulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (three or) four (Melianthus), or (four or) five (to seven; Bersama) connate carpels. Ovary superior or semi-inferior, usually quadrilocular or quinquelocular, lobate. Style single, simple. Stigma entire, punctate or somewhat widened and ridged, non-papillate?, Wet type. Male flowers in Bersama with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation usually axile to apical (in Bersama basal), with intrusive placentae. Ovule one (Bersama) or two to five (Melianthus), anatropous, pendulous, horizontal (Melianthus) or ascending (Bersama), apotropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal (Melianthus) or bistomal (Bersama). Outer integument three to seven cell layers thick. Inner integument two to four cell layers thick. Funicular obturator? Hypostase present, later massive. Nucellar cap present in Melianthus. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis asterad.

Fruit A membranous caducous (some species of Melianthus) or coriaceous to woody persistent capsule, loculicidal (in Bersama also partially septicidal).

Seeds Aril usually absent (present in Bersama). Seed coat exotestal. Testa multiplicative (to 20 or more cell layers). Exotesta palisade, crystalliferous, with thick outer cell walls. Mesotestal and endotestal cells thin-walled, with calciumoxalate as styloids and other crystal types. Tegmen crushed, unlignified. Mesotegmic cells elongating. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, oily and sometimes starchy, thick-walled (Bersama) or with amyloid (xyloglucans; Melianthus). Embryo small, straight, well differentiated, with chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, narrow. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 18, 19

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols (quercetin, myricetin), anthocyanins (in roots), oleanolic acid derivatives, ellagic acid, toxic bufadienolides (cardiac glycosides), glucuronide triterpenoid saponins, and inulin present. Proanthocyanidins, saponins, cyanogenic compounds, rutinosides, and cyanolipids not found.

Use Ornamental plants, medicinal plants, timber, carpentries, aromatic substances (incense wood).

Systematics Bersama (8; B. abyssinica, B. lucens, B. palustris, B. stayneri, B. swinnyi, B. swynnertonii, B. tysoniana, B. yangambiensis; tropical and southern Africa), Melianthus (6; M. comosus, M. dregeanus, M. elongatus, M. major, M. pectinatus, M. villosus; southern Africa).

Melianthaceae are sister-group to Francoaceae.

Literature

Adams KL, Palmer JD. 2003. Evolution of mitochondrial gene content: gene loss and transfer to the nucleus. – Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 29: 380-395.

Aedo C. 1997. Twelve new names in Geranium L. (Geraniaceae). – Kew Bull. 52: 725-727.

Aedo C. 2001. Taxonomic revision of Geranium sect. Brasiliensia (Geraniaceae). – Syst. Bot. 26: 205-215.

Aedo C. 2016. Taxonomic revision of Geranium sect. Polyantha (Geraniaceae). – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 101: 611-635.

Aedo C. 2017. Taxonomic revision of Geranium Sect. Ruberta and Unguiculata (Geraniaceae). – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 102: 409-465.

Aedo C, Muñoz-Garmendia F, Pando F. 1998. World checklist of Geranium. – An. Jard. Bot. Madrid 56: 211-252.

Aedo C, Aldasoro JJ, Navarro C. 2002. Revision of Geranium sections Azorelloidea, Neoandina, and Paramensia (Geraniaceae). – Blumea 47: 205-297.

Aedo C, Aldasoro JJ, Saez L, Navarro C. 2003. Taxonomic revision of Geranium sect. Gracilia (Geraniaceae). – Brittonia 55: 93-126.

Aedo C, Navarro C, Alarcón ML. 2005. Taxonomic revision of Geranium sections Andina and Chilensia (Geraniaceae). – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 149: 1-68.

Aedo C, Fiz O, Alarcon ML, Navarro C, Aldasoro JJ. 2005. Taxonomic revision of Geranium sect. Dissecta (Geraniaceae). – Syst. Bot. 30: 533-558.

Aedo C, García MÁ, Alarc´n ML, Aldasoro JJ, Navarro C. 2007. Taxonomic revision of Geranium subsect. Mediterranea (Geraniaceae). – Syst. Bot. 32: 93-128.

Aedo C, Barberá P, Buira A. 2016. Taxonomic revision of Geranium sect. Trilopha (Geraniaceae). – Syst. Bot. 41: 354-377.

Agarwal JS, Rastogi RP. 1976. Queretaroic (30) caffeate and other constituents of Melianthus major. – Phytochemistry 15: 430-431.

Alarcón ML, Aldasoro JJ, Aedo C, Navarro C. 2003. A new species of Erodium L’Hér. (Geraniaceae) endemic to Australia. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 141: 243-250.

Alarcón ML, Vargas P, Séz L, Molera J, Aldasoro JJ. 2012. Genetic diversity of mountain plants: two migration episodes of Mediterranean Erodium (Geraniaceae). – Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 63: 866-876.

Albers F. 1988. Strategies in chromosome evolution in Pelargonium (Geraniaceae). – Monogr. Syst. Bot. Missouri Bot. Gard. 25: 499-502.

Albers F. 1990. Comparative karyological studies in Geraniaceae on family, genus, and section level. – In: Vorster P (ed), Proceedings of the 1st International Geraniaceae Symposium, University of Stellenbosch, Republic of South Africa, pp. 115-122.

Albers F. 1996a. The taxonomic status of Sarcocaulon (Geraniaceae). – South Afr. J. Bot. 62: 345-347.

Albers F. 1996b. The generic status of Sarcocaulon (Geraniaceae). – I. O.S. Bull. 6: 51.

Albers F. 2002. Geraniaceae. – In: Eggli U (ed), Illustrated handbook of succulent plants. Dicotyledons, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 241-272.

Albers F, Becker M. 2010. Phylogeny and speciation in succulent Geraniaceae (Geraniales). – Schumannia 6: 59-67.

Albers F, Walt JJA van der. 1984. Untersuchungen zur Karyologie und Mikrosporogenese von Pelargonium sect. Pelargonium (Geraniaceae). – Plant Syst. Evol. 147: 177-188.

Albers F, Walt JJA van der. 2006. Geraniaceae. – In: Kubitzki K (ed), The families and genera of vascular plants IX. Flowering plants. Eudicots. Berberidopsidales, Buxales, Crossosomatales, Fabales p. p., Geraniales, Gunnerales, Myrtales p. p., Proteales, Saxifragales, Vitales, Zygophyllales, Clusiaceae Alliance, Passifloraceae Alliance, Dilleniaceae, Huaceae, Picramniaceae, Sabiaceae, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 157-167.

Albers F, Gibby M, Austmann M. 1992. A reappraisal of Pelargonium sect. Ligularia (Geraniaceae). – Plant syst. Evol. 179: 257-276.

Aldasoro JJ, Aedo C, Navarro C. 2000. Insect attracting structure on Erodium petals (Geraniaceae). – Plant Biol. 2: 471-481.

Aldasoro JJ, Navarro C, Vargas P, Aedo C. 2001. Anatomy, morphology, and cladistic analysis of Monsonia L. (Geraniaceae). – An. Jard. Bot. Madrid 59: 75-100.

Aldasoro JJ, Navarro C, Vargas P, Saez L, Aedo C. 2002. California, a new genus of Geraniaceae endemic to the southwest of North America. – An. Jard. Bot. Madrid 59: 209-216.

Al-Nowaihi AS, Khalifa SF. 1973. Studies on some taxa of the Geraniales II. Floral morphology of certain Linaceae, Rutaceae and Geraniaceae with a reference to the consistency of some characters. – J. Indian Bot. Soc. 52: 198-206.

Al-Shammary KI, Gornall RJ. 1994. Trichome anatomy of the Saxifragaceae s.l. from the Southern Hemisphere. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 114: 99-131.

Anderson LA. 1968. Occurrence of oleanolic acid acetate and ellagic acid in Melianthus comosus Vahl. – J. South Afr. Chem. Inst. 21: 91-92.

Anderson LA, Koekemoer JM. 1968. Chemistry of Melianthus comosus Vahl 2. Isolation of hellebrigenin 3-acetate and other unidentified bufadienolides from rootbark of Melianthus comosus Vahl. – J. South Afr. Chem. Inst. 21: 155-159.

Anderson LA, Koekemoer JM. 1969. Chemistry of Melianthus comosus Vahl 3. Constitution of melianthugenin and melianthusigenin, new bufadienolides from root-bark. – J. South Afr. Chem. Inst. 22: 191-197.

Andrews S. 1987. Melianthus villosus. – Kew Mag. 4: 123-127.

Ariza Espinar L. 1995a. Flora Fanerogámica Argentina fasc. 8, 129b. Vivianiaceae. – CONICET, Córdoba, Argentina.

Ariza Espinar L. 1995b. Flora Fanerogámica Argentina fasc. 18, 129a. Ledocarpaceae. – CONICET, Córdoba, Argentina.

Bakker FT, Helbrügge D, Culham A, Gibby M. 1998. Phylogenetic relationships within Pelargonium section Peristera (Geraniaceae) inferred from nrDNA and cpDNA sequence comparisons. – Plant Syst. Evol. 211: 273-287.

Bakker FT, Culham A, Daugherty LC, Gibby M. 1999. A trnL-trnF based phylogeny for species of Pelargonium (Geraniaceae) with small chromosomes. – Plant Syst. Evol. 216: 309-324.

Bakker FT, Culham A, Pankhurst CE, Gibby M. 2000. Mitochondrial and chloroplast DNA-based phylogeny of Pelargonium (Geraniaceae). – Amer. J. Bot. 87: 727-734.

Bakker FT, Culham A, Hettiarachi P, Touloumenidou T, Gibby M. 2004. Phylogeny of Pelargonium (Geraniaceae) based on DNA sequences from three genomes. – Taxon 53: 17-28.

Bakker FT, Culham A, Marais EM, Gubby M. 2005. Nested radiation in Cape Pelargonium. – In: Bakker FT, Chatrou LW, Gravendeel B, Pelser PB (eds), Plant species-level systematics: new perspectives on pattern and process, Regnum Vegetabile 143, A. R. G. Gantner, Ruggel, Liechtenstein, pp. 75-100.

Bakker FT, Breman F, Merckx V. 2006. DNA sequence evolution in fast-evolving mitochondrial DNA nad1 exons in Geraniaceae and Plantaginaceae. – Taxon 55: 887-896.

Bate-Smith EC. 1972. Ellagitannin content of leaves of Geranium species. – Phytochemistry 11: 1755-1757.

Bate-Smith EC. 1973. Chemotaxonomy of Geranium. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 67: 347-359.

Becker M, Albers F. 2005. Pelargonium adriaanii (Geraniaceae), a new species from the Northern Cape Province, South Africa. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 126: 153-161.

Behnke H-D, Mabry TJ. 1977. S-Type sieve-element plastids and anthocyanins in Vivianiaceae: evidence against its inclusion into the Centrospermae. – Plant Syst. Evol. 126: 371-375.

Boesewinkel FD. 1979. Development of ovule and testa of Geranium pratense L. and some other representatives of the Geraniaceae. – Acta Bot. Neerl. 28: 333-348.

Boesewinkel FD. 1988. The seed structure and taxonomic relationships of Hypseocharis Remy. – Acta Bot. Neerl. 37: 111-120.

Boesewinkel FD. 1997. Seed structure and phylogenetic relationships of the Geraniales. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 119: 277-291.

Boesewinkel FD, Been W. 1979. Development of ovule and testa of Geranium pratense L. and some other representatives of the Geraniaceae. – Acta Bot. Neerl. 28: 335-348.

Bohm BA, Chan J. 1992. Flavonoids and affinities of Greyiaceae with a discussion of the occurrence of B-ring deoxyflavonoids in dicotyledonous families. – Syst. Bot. 17: 272-281.

Bohm BA, Collins FW, Bose R. 1977. Flavonoids of Bergenia, Francoa, and Parnassia. – Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 13: 221-233.

Bohm BA, Donevan LS, Bhat UG. 1986. Flavonoids of some species of Bergenia, Francoa, Parnassia and Lepuropetalon. – Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 14: 75-77.

Bortenschlager S. 1967. Vorläufige Mitteilungen zur Pollenmorphologie in der Familie der Geraniaceen und ihre systematische Bedeutung. – Grana Palynol. 7: 400-468.

Campagna ML, Downie SR. 1998. The intron in chloroplast gene rpl16 is missing from the flowering plant families Geraniaceae, Goodeniaceae and Plumbaginaceae. – Trans. Illinois State Acad. Sci. 9: 1-11.

Carlquist SJ. 1986. Wood anatomy and familial status of Viviania. – Aliso 11: 159-165.

Carlquist SJ, Bissing DR. 1976. Leaf anatomy of Hawaiian Geraniums in relation to ecology and taxonomy. – Biotropica 8: 248-259.

Carolin RC. 1958. The species of the genus Erodium L’Hér. endemic to Australia. – Proc. Linn. Soc. New South Wales 83: 92-100.

Carolin RC. 1964. The genus Geranium L. in the south western Pacific area. – Proc. Linn. Soc. New South Wales 89: 326-361.

Chumley TW, Palmer JD, Mower JP, Fourcade HM, Calie PJ, Boore JL, Jansen RK. 2006. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Pelargonium x hortorum: organization and evolution of the largest and most highly rearranged chloroplast genome of land plants. – Mol. Biol. Evol. 23: 2175-2190.

Craib C. 1995. The Sarcocaulons of southern Africa. – Hystrix 1: 1-60.

Dahlgren G. 1980. Cytological and morphological investigation of the genus Erodium L’Hér. in the Aegean. – Bot. Not. 133: 491-514.

Dahlgren KVO. 1930. Zur Embryologie der Saxifragaceen. – Svensk Bot. Tidskr. 24: 429-448.

Dahlgren R, Wyk AE van. 1988. Structures and relationships of families endemic to or centered in southern Africa. – Monogr. Syst. Bot. Missouri Bot. Gard. 25: 1-94.

Demarne F-E. 1990. Essential oils in Pelargonium, sect. Pelargonium. – In: Vorster P (ed), Proceedings of the 1st International Geraniaceae symposium, University of Stellenbosch, Republic of South Africa, pp. 245-268.

Dlamini T. 1999. Systematic studies in the genus Melianthus L. (Melianthaceae). – M.Sc. thesis, University of Cape Town, Republic of South Africa.

Doweld AB. 1998a. The systematic relevance of phermatology and carpology of Bersama and Melianthus (Melianthaceae). – Ann. Bot. 83: 321-333.

Doweld AB. 1998b. The melianthaceous seed and its rhamnaceous affinity. – Acta Bot. Malac. 23: 71-88.

Doweld AB. 2001. The systematic relevance of fruit and seed structure in Bersama and Melianthus. – Plant Syst. Evol. 227: 75-103.

Dreyer LL, Marais EM. 2000. Section Reniformia, a new section in the genus Pelargonium (Geraniaceae). – South Afr. J. Bot. 66: 44-51.

Dreyer LL, Leistner OA, Burgoyne P, Smith GF. 1997. Sarcocaulon: genus or section of Monsonia (Geraniaceae)? – South Afr. J. Bot. 63: 240.

Dunbar KB, Stephens CT. 1992. Resistance in seedlings of the family Geraniaceae to bacterial blight caused by Xanthomonas campestris pv. pelargonii. – Plant Disease 76: 693-695.

El-Oqlah AA. 1989. A revision of the genus Erodium L’Héritier in the Middle East. – Feddes Repert. 100: 3-4.

Endress PK. 2010. Synorganisation without organ fusion in the flowers of Geranium robertianum (Geraniaceae) and its not so trivial obdiplostemony. – Ann. Bot. 106: 687-695.

Engler A. 1891. Saxifragaceae. – In: Engler A, Prantl K (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien III(2a), W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 41-93.

Engler A. 1930. Saxifragaceae. – In: Engler A, Harms H (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien, 2. Aufl., Bd. 18a, W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 74-226.

Fehrenbach S, Barthlott W. 1988. Mikromorphologie der Epicuticular-Wachse der Rosales s.l. und deren systematische Gliederung. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 109: 407-428.

Ferreira JPR, Hessemer G, Campestrino S, Trevisan R. 2016. A revision of the extra-Andean Vivianiaceae. – Phytotaxa 246: 23-36.

Fiz O, Vargas P, Alarcón ML, Aldasoro JJ. 2006. Phylogenetic relationships and evolution in Erodium (Geraniaceae) based on trnL-trnF sequences. – Syst. Bot. 31: 739-763.

Fiz O, Vargas P, Alarcón ML, Aedo M, Garcia JL, Aldasoro JJ. 2008. Phylogeny and historical biogeography of Geraniaceae in relation to climate changes and pollination ecology. – Syst. Bot. 33: 326-342.

Fiz-Palacios O, Vargas P, Vila R, Papadopoulos AST, Aldasoro JJ. 2010. The uneven phylogeny and biogeography of Erodium (Geraniaceae): radiations in the Mediterranean and recent recurrent intercontinental colonization. – Ann. Bot. 106: 871-884.

Gama-Arachchige NS, Baskin JM, Geneve RL, Baskin CC. 2010. Identification and characterization of the water gap in physically dormant seeds of Geraniaceae, with special reference to Geranium carolinianum. – Ann. Bot. 105: 977-990.

Gauger W. 1937. Ergebnisse einer zytologischen Untersuchung der Familie der Geraniaceae I. – Planta 26: 529-531.

Gäumann E. 1919. Studien über die Entwicklungsgeschichte einiger Saxifragales. – Rec. Trav. Bot. Néerl. 16: 85-322.

Gibby M, Hinnah S, Albers F, Marais EM. 1996. Cytological variation and evolution within Pelargonium sect. Hoarea. – Plant Syst. Evol. 203: 111-142.

Goldblatt P. 1978. Chromosome number in two cytologically unknown New World families, Tovariaceae and Vivianiaceae. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 65: 776-777.

Gornall RJ, Al-Shammary KIA. 1998. Francoaceae. – In: Cutler DF, Gregory M (eds), Anatomy of the dicotyledons, Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp. 243-244.

Gornall RJ, Bohm BA, Dahlgren R. 1979. The distribution of flavonoids in the angiosperms. – Bot. Not. 132: 1-30.

Green BB. 1978. Comparative ecology of Geranium richardsonii and Geranium nervosum. – Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 105: 108-113.

Gregory M. 1998. Greyiaceae. – In: Cutler DF, Gregory M (eds), Anatomy of the dicotyledons, Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp. 238-242.

Guérin P. 1901. Développement de la graine et en particulier du tégument séminal de quelques Sapindacées. – J. Bot. (Morot) 15: 336-362.

Guisinger MM, Kuehl JV, Boore JL, Jansen RK. 2008. Genome-wide analyses of Geraniaceae plastid DNA reveal unprecedented patterns of increased nucleotide substitutions. – Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105: 18424-18429.

Guisinger MM, Kuehl JV, Boore JL, Jansen RK. 2011. Extreme reconfiguration of plastid genomes in the angiosperm family Geraniaceae: rearrangements, repeats, and codon usage. – Mol. Biol. Evol. 28: 583-600.

Guittonneau G-G. 1963. Nouvelles etudes taxonomiques sur les espèces d’Erodium du basin méditerranéen occidental II. – Bull. Soc. Bot. France 110: 43-48.

Guittonneau G-G. 1964. Contribution à l’étude caryologique du genre Erodium L’Hér. I. – Bull. Soc. Bot. France 111: 1-4.

Guittonneau G-G. 1965. Contribution à l’étude caryosystématique du genre Erodium L’Hér. II. – Bull. Soc. Bot. France 112: 25-32.

Guittonneau G-G. 1966. Contribution à l’étude caryosystématique du genre Erodium L’Hér. III. – Bull. Soc. Bot. France 113: 3-11.

Guittonneau G-G. 1967. Contribution à l’étude caryosystématique du genre Erodium L’Hér. IV. – Bull. Soc. Bot. France 114: 32-42.

Guittonneau G-G. 1972. Contribution à l’étude biosystématique du genre Erodium L’Hér. dans le basin méditerranéen occidental. – Boissiera 20: 9-154.

Guittonneau G-G. 1990. Taxonomy, ecology, and phylogeny of the genus Erodium L’Hér. in the Mediterranean region. – In: Vorster P (ed), Proceedings of the 1st International Geraniaceae Symposium, University of Stellenbosch, Republic of South Africa, pp. 69-91.

Gürke M. 1896. Melianthaceae. – In: Engler A, Prantl K (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien III(5), W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 374-383.

Halfdan-Nielsen B. 1996. Five new species of Geranium (Geraniaceae) from Ecuador. – Nord. J. Bot. 16: 267-275.

Hallier H. 1923. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Linaceae (DC. 1819) Dumort. 25. Lepidobotrys Engl., die Oxalidaceen und die Geraniaceen. – Beih. Bot. Centralbl. 39: 1-178.

Halloy SRP. 1998. A new and rare, plate-shaped Geranium from the Cumbres Calchaquíes, Tucumán, Argentina. – Brittonia 50: 467-472.

Hessing MB. 1989. Variation in self-fertility and floral characters of Geranium caespitosum (Geraniaceae) along an elevational gradient. – Plant Syst. Evol. 166: 225-241.

Hewson HJ. 1985. Melianthaceae. – In: George AS (ed), Flora of Australia 25, Australian Government Publ. Service, Canberra, pp. 1-2.

Hideux M, Ferguson IK. 1976. The stereostructure of the exine and its evolutionary significance in Saxifragaceae sensu lato. – In: Ferguson IK, Muller J (eds), The evolutionary significance of the exine, Linn. Soc. Symposium, No. 1, Academic Press, London and New York, pp. 327-377.

Hilger HH. 1978. Der multilakunäre Knoten einiger Melianthus- und Greyia-Arten in Vergleich mit anderen Knotentypen. – Flora 167: 165-176.

Hilger HH. 1978. Leitbündelverbindungen in den Rhachisknoten der Fiederblätter von Melianthus comosus, M. minor, M. major und Bersama abyssinica (Melianthaceae, Sapindales). – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 100: 221-236.

Hilliard OM, Burtt BL. 1985. A revision of Geranium in Africa South of the Limpopo. – Notes Roy. Bot. Gard. Edinb. 42: 171-225.

Hofmann U. 1987. Der Bau des Gynoeceums von Tropaeolum und Pelargonium. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 108: 439-448.

Hooker JD. 1873. On Melianthus trimenianus H. F. and the affinities of Greyia sutherlandii. – J. Bot. 11: 353-358.

Hunziker AT, Ariza Espinar L. 1973. Aporte a la rehabilitación de Ledocarpaceae, familia monotipica. – Kurtziana 7: 233-240.

Jackson BP, Jethwa KR. 1973. Morphology and anatomy of the leaves of Bersama abyssinica from Kenya and Uganda. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 66: 245-257.

James CM, Gibby M, Barrett JA. 2004. Molecular studies in Pelargonium (Geraniaceae). A taxonomic appraisal of section Ciconium and the origin of the “Zonal” and “Ivy-leaved” cultivars. – Plant Syst. Evol. 243: 131-146.

Jay MM. 1967. Recherches chimiotaxinomiques sur les plantes vasculaires: les flavonoides de Greyia sutherlandii Harv. – Compt. Rend. Acad. Sci. Paris 265: 1086-1088.

Jay MM. 1970 [1971]. Quelques problèmes taxinomiques et phylogénétiques des Saxifragacées vus à la lumière de la biochimie flavonique. – Bull. Mus. Natl. Hist. Nat. Paris, sér. II, 42: 754-775.

Jeiter J, Weigend M, Hilger HH. 2017. Geraniales flowers revisited: evolutionary trends in floral nectaries. – Ann. Bot. 119: 395-408.

Jeiter J, Hilger HJ, Smets EF, Weigend M. 2017. The relationship between nectaries and floral architecture: a case study in Geraniaceae and Hypseocharitaceae. – Ann. Bot. 120: 791-803.

Johnson MAT, Özhatay N. 1988. The distribution and cytology of Turkish Pelargonium (Geraniaceae). – Kew Bull. 43: 139-148.

Jones CS, Price RA. 1996. Diversity and evolution of seedling Baupläne in Pelargonium (Geraniaceae). – Aliso 14: 281-295.

Jones CS, Bakker FT, Schlichting CD, Nicotra AB. 2009. Leaf shape evolution in the South African genus Pelargonium L’Hér. (Geraniaceae). – Evolution 63: 479-497.

Kandori I. 2002. Diverse visitors with various pollinator importance and temporal change in the important pollinators of Geranium thunbergii (Geraniaceae). – Ecol. Res. 17: 283-294.

Kenda G. 1956. Das Hypoderm der Geraniaceen-Kelchblätter. – Planta 6: 206-210.

Kers LE. 1968. Contributions towards a revision of Monsonia (Geraniaceae). – Bot. Not. 121: 44-50.

Kers LE. 1971. Monsonia parvifolia Schinz (Geraniaceae), a species with concealed spurs. – Bot. Not. 124: 208-212.

Khushalani I. 1963. Floral morphology and embryology of Melianthus major Linnaeus. – Phyton (Buenos Aires) 10: 145-156.

Killick DJB. 1976. Greyia sutherlandii. – In: Killick DJB (ed), Flowering plants of Africa 44, Pretoria.

Klopfer K. 1972. Beiträge zur floralen Morphogenese und Histogenese der Saxifragaceae 7. Parnassia palustris und Francoa sonchifolia. – Flora 161B: 320-332.

Knuth R. 1931. Geraniaceae. – In: Engler A (†), Harms H, Pax F (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien, 2. Aufl., Bd. 19a, W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 43-66.

Koekemoer JM, Anderson LA, Pachler KGR. 1970. Chemistry of Melianthus comosus Vahl 4. 6-beta-acetoxymelianthugenin, a new toxic principle from root-bark. – J. South Afr. Chem. Inst. 23: 146-153.

Koekemoer JM, Anderson LA, Pachler KGR. 1971. Chemistry of Melianthus comosus Vahl 5. 2 novel bufadienolides from root-bark. – J. South Afr. Chem. Inst. 24: 75-86.

Koekemoer JM, Vermeulen NMJ, Anderson LA. 1974. Chemistry of Melianthus comosus Vahl 6. Structure of a new triterpenoid acid from root-bark. – J. South Afr. Chem. Inst. 27: 131-136.

Kokwaro J. 1969. Notes on East African Geraniaceae. – Kew Bull. 23: 527-530.

Kokwaro J. 1971. Geraniaceae. – In: Milne-Redhead E, Polhill RM (eds), Flora of Tropical East Africa, Crown Agents for Oversea Governments and Administrations, London, pp. 1-24.

Kolodziej H, Kayser O. 1998. Pelargonium sidoides DC. Neueste Erkenntnisse zum Verständnis des Phytotherapeutikums Umckaloabo. – Zeitschr. Phytotherapie 19: 141-151.

Krach JE. 1976. Samenanatomie der Rosifloren I. Die Samen der Saxifragaceae. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 97: 1-60.

Kumar A. 1976. Studies in Geraniales II. The floral anatomy. – J. Indian Bot. Soc. 55: 233-253.

Kupchan SM, Ognyanov I. 1969. The isolation and structural elucidation of a novel naturally-occurring bufadienolide orthoacetate. – Tetrahedron Lett. 10: 1709-1712.

Kupchan SM, Hemingway RJ, Hemingway JC. 1968. The isolation and characterization of hellebrigenin C-acetate and hellebrigenin 3,5-diacetate, bufadienolide tumor inhibitors from Bersama abyssinica. – Tetrahedron Lett. 9: 149-152.

Larsen K. 1958. Cytological and experimental studies on the genus Erodium with the special references to the collective species E. cicutarium L’Hér. – Biol. Meddel. Kongl. Danske Vidensk. Selsk. 23: 1-25.

Laundon JR. 1961. Notes on Geranium in Africa and Arabia. – Bol. Soc. Brot. 35: 59-73.

Laundon JR. 1963. Geranium. – In: Exell AW, Fernandes A, Wild H (eds), Flora Zambesiaca 2, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, pp. 131-136.

Lefor MWM. 1975. A taxonomic revision of the Vivianiaceae. – Univ. Connecticut Occas. Papers, Biol. Sci., Ser. II, 15: 225-255.

Legault A. 1908. Recherches anatomiques sur l’appareil végétatif des Géraniacées. – Compt. Rend. Acad. Sci. Paris CXLVII, no 7.

Linder HP. 2006. Melianthaceae. – In: Kubitzki K (ed), The families and genera of vascular plants IX. Flowering plants. Eudicots. Berberidopsidales, Buxales, Crossosomatales, Fabales p. p., Geraniales, Gunnerales, Myrtales p. p., Proteales, Saxifragales, Vitales, Zygophyllales, Clusiaceae Alliance, Passifloraceae Alliance, Dilleniaceae, Huaceae, Picramniaceae, Sabiaceae, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 250-259.

Linder HP, Dlamini T, Henning J, Verboom GA. 2006. The evolutionary history of Melianthus (Melianthaceae). – Amer. J. Bot. 93: 1052-1064.

Link DA. 1989. Die Nektarien der Geraniales. Morphologie, Anatomie, Histologie, Blütenökologische Bedeutung und Konsequenzen für die Systematik. – Ph.D. diss., Johannes-Gutenberg-Universität, Mainz, Germany.

Link DA. 1990. The nectaries of Geraniaceae. – In: Vorster P (ed), Proceedings of the 1st International Geraniaceae Symposium, University of Stellenbosch, Republic of South Africa, pp. 25-43.

Lis-Balchin M. 1990. the commercial usefulness of the Geraniaceae, including their potential in the perfumery, food manufacture, and pharmacological industries. – In: Vorster P (ed), Proceedings of the 1st International Geraniaceae Symposium, University of Stellenbosch, Republic of South Africa, pp. 269-277.

Lis-Balchin M (ed). 2002. Geranium and Pelargonium: the genera Geranium and Pelargonium. – Taylor and Francis, London.

Loon JC van. 1984a. Chromosome numbers in Geranium from Europe I. The perennial species. – Proc. Kon. Nederl. Akad. Wetensch., C, 87: 263-277.

Loon JC van 1984b. Chromosome numbers in Geranium from Europe II. The annual species. – Proc. Kon. Nederl. Akad. Wetensch., C, 84: 279-296.

Loon JC van 1984c. Hybridization experiments in Geranium. – Genetica 65: 167-171.

McDonald DJ, Walt JJA van der. 1992. Observations on the pollination of Pelargonium tricolor, section Campylia (Geraniaceae). – South Afr. J. Bot. 58: 386-392.

Marais EM. 2014. One name change and three

new species of Pelargonium, section Hoarea (Geraniaceae) from the Western Cape

Province. – South Afr. J. Bot. 90: 118-127.

Marais EM. 2016. Five new species of Pelargonium, section Hoarea (Geraniaceae), from the Western and Northern Cape Provinces of South Africa. – South Afr. J. Bot. 103: 145-155.

Marais EM. 2017. Three new geophytic species of Pelargonium (Geraniaceae) from the Western Cape Province, South Africa and their relationships within section Hoarea. – South Afr. J. Bot. 113: 261-269.

Marcussen T, Meseguer AS. 2017. Species-level phylogeny, fruit evolution and diversification history of Geranium (Geraniaceae). – Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 110: 134-149.

Mathur S. 1977. Embryology of Melianthus major L. 1. Microsporangium and pollen. – Curr. Sci. 46: 820-821.

Mauritzon J. 1933. Studien über Embryologie der Familien Crassulaceae und Saxifragaceae. – Ph.D. diss, University of Lund, Sweden.

Mauritzon J. 1936. Zur Embryologie und systematische Abgrenzung der Reihen Terebinthales und Celastrales. – Bot. Not. 1936: 161-212.

Medeiros AC, St. John H. 1988. Geranium hananense (Geraniaceae), a new species from Maui, Hawaiian Islands. – Brittonia 40: 214-220.

Meisert A, Schulz D, Lehmann H. 2001. The ultrastructure and development of the light line in the Geraniaceae seed coat. – Plant Biol. 3: 351-356.

Merxmüller H, Schreiber A. 1965. Drei verkannte Monsonien der Südnamib. – Mitt. Bot. Staatssamml. München 5: 551-562.

Meve U. 1995. Autogamie bei Pelargonium-Wildarten. – Palmengarten 59: 100-108.

Mikkelsen KS, Seberg O. 2001. Morphometric analysis of the Bersama abyssinica Fresen. complex (Melianthaceae) in East Africa. – Plant Syst. Evol. 227: 157-182.

Moffett RO. 1979. The genus Sarcocaulon. – Bothalia 12: 581-613.

Moffett RO. 1997. The taxonomic status of Sarcocaulon. – South Afr. J. Bot. 63: 239-240.

Monkhe T, Mulholland D, Nicholls G. 1998. Triterpenoids from Bersama swinnyi. – Phytochemistry 49: 1819-1820.

Moore HE Jr. 1943. A revision of the genus Geranium in Mexico and Central America. – Contr. Gray Herb. Harvard Univ. CXLVI: 1-180.

Moore HE Jr. 1961. A remarkable new Geranium from Ecuador. – Brittonia 13: 141-144.

Morf E. 1950. Vergleichend-morphologische Untersuchungen am Gynoeceum der Saxifragaceen. – Ber. Schweiz. Bot. Ges. 60: 516-590.

Morgan DR, Soltis DE. 1993. Phylogenetic relationships among members of Saxifragaceae sensu lato based on rbcL sequence data. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 80: 631-660.

Mosebach G. 1934. Die Fruchtstielschwellung der Oxalidaceen und Geraniaceen. – Jahrb. Wiss. Bot. 79: 353-384.

Müller T. 1963. 37. Geraniaceae. – In: Exell AW, Fernandes A, Wild H (eds), Flora Zambesiaca 2 (Part 1), Crown Agents for Oversea Governments and Administrations, London, pp. 130-149.

Narayana HS, Arora PK. 1963. Floral anatomy of Monsonia senegalensis Guill. & Perr. – Curr. Sci. 32: 184-185.

Narayana LL. 1970. Geraniaceae. – In: Proceedings of the symposium on comparative embryology of angiosperms, Indian National Science Academy, New Delhi, pp. 117-119.

Narayana LL, Rama Devi D. 1995. Floral anatomy and systematic position of the Vivianiaceae. – Plant Syst. Evol. 196: 123-129.

Nemirovich-Danchenko EN. 1994. The seed structure of the species of the genera Francoa and Tetilla (Francoaceae). – Bot. Žurn. 79: 109-114. [In Russian]

Nemirovich-Danchenko EN. 1995. The seed structure in Greyia sutherlandii (Greyiaceae). – Bot. Žurn. 80: 99-104. [In Russian]

Okuda T, Mori k, Hatano T. 1980. The distribution of geraniin and mallotusinic acid in the order Geraniales. – Phytochemistry 19: 547-551.

Oltmann O. 1971. Pollenmorphologisch-systematische Untersuchungen innerhalb der Geraniales. – Diss. Bot. 11: 1-163.

Palmer JD, Nugent JM, Herbon LA. 1987. Unusual structure of geranium chloroplast DNA: a triple-sized inverted repeat, extensive gene duplications, multiple inversions and two repeat families. – Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84: 769-773.

Parkinson CL, Mower JP, Qiu Y-L, Shirk AJ, Song K, Young ND, dePamphilis CW, Palmer JD. 2005. Multiple major increases and decreases in mitochondrial substitution rates in the plant family Geraniaceae. – BMC Evol. Biol. 5: 73. www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/5/73

Pax DL, Price RA, Michaels HJ. 1997. Phylogenetic position of the Hawaiian geraniums based on rbcL sequences. – Amer. J. Bot. 84: 72-78.

Pedro L, Campos P, Pais MS. 1990. Morphology, ontogeny and histochemistry of secretory trichomes of Geranium robertianum (Geraniaceae). – Nord. J. Bot. 10: 501-509.

Philipp M. 1985. Reproductive biology of Geranium sessiliflorum 1. Flower and flowering biology. – New Zealand J. Bot. 23: 567-580.

Philipp M, Hansen T. 2000. The influence of plant and corolla size on pollen deposition and seed set in Geranium sanguineum (Geraniaceae). – Nord. J. Bot. 20: 129-140.

Phillips EP. 1922. The genus Bersama. – Bothalia 1: 33-39.

Price RA, Palmer JD. 1993. Phylogenetic relationships of the Geraniaceae and Geraniales from rbcL sequence comparisons. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 80: 661-671.

Price RA, Calie PJ, Downie SR, Logsdon JM Jr, Palmer JD. 1990. Chloroplast DNA variation in the Geraniaceae – a preliminary report. – In: Vorster P (ed), Proceedings of the 1st International Geraniaceae Symposium, University of Stellenbosch, Republic of South Africa, pp. 237-244.

Rama Devi D. 1991. Floral anatomy of Hypseocharis (Oxalidaceae) with a discussion of its systematic position. – Plant Syst. Evol. 177: 161-164.

Ramamonjiarisoa BA. 1980. Comparative anatomy and systematics of African and Malagasy woody Saxifragaceae sensu lato. – Ph.D. diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts.

Reiche K. 1896. Geraniaceae. – In: Engler A, Prantl K (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien III(4), W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 1-14.

Ronse De Craene L-P, Smets E. 1999. Similarities in floral ontogeny and anatomy between the genera Francoa (Francoaceae) and Greyia (Greyiaceae). – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 160: 377-393.

Ronse De Craene L-P, Linder HP, Dlamini T, Smets EF. 2001. Evolution and development of floral diversity of Melianthaceae, an enigmatic southern African family. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 162: 59-82.

Sant Prasad Reddy T, Narayana LL. 1986. Chemotaxonomy of Geraniaceae. – J. Indian Bot. Soc. 65: 228-235.

Sauer H. 1933. Blüte und Frucht der Oxalidaceen, Linaceen, Geraniaceen, Tropaeolaceen und Balsaminaceen. Vergleichend-entwicklungsgeschichtliche Untersuchungen. – Planta 19: 417-481.

Scheltema AG, Walt JJA van der. 1990. Taxonomic revision of Pelargonium sect. Jenkinsonia (Geraniaceae). – South Afr. J. Bot. 59: 259-264.

Schoenagel E. 1931. Chromosomenzahl und Phylogenie der Saxifragaceen. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 64: 266-308.

Schonland S. 1914. Notes on the genus Greyia Hook. and Harv. – Rec. Albany Mus. 3: 40-51.

Schürhoff PN. 1924. Zytologische Untersuchungen in der Reihe der Geraniales. – Jahrb. Wiss. Bot. 63: 707-759.

Seigler DS, Kawahara W. 1976. New reports of cyanolipids from sapindaceous plants. – Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 4: 263-265.

Slanis AC, Grau A. 2001. El género Hypseocharis (Oxalidaceae) en la Argentina. – Darwiniana 39: 343-352.

Soltis DE, Soltis PS. 1997. Phylogenetic relationships in Saxifragaceae sensu lato: a comparison of topologies based on 18S rDNA and rbcL sequences. – Amer. J. Bot. 84: 504-522.

Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Clegg MT, Durbin M. 1990. rbcL sequence divergence and phylogenetic relationships in Saxifragaceae sensu lato. – Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87: 4640-4644.

Stafford PJ, Gibby M. 1992. Pollen morphology of the genus Pelargonium (Geraniaceae). – Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 71: 79-109.

Stamp NE. 1984. Self-burial behaviour of Erodium cicutarium seeds. – J. Ecol. 72: 611-620.

Stamp NE. 1989. Seed dispersal of four sympatric grassland annual species of Erodium. – J. Ecol. 77: 1005-1020.

Steele PR, Guisinger-Bellian M, Linder CR, Jansen RK. 2008. Phylogenetic utility of 141 low-copy nuclear regions in taxa at different taxonomic levels in two distantly related families of rosids. – Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 48: 1013-1026.

Steyn EMA. 1974a. Leaf anatomy of Greyia Hooker & Harvey (Greyiaceae). – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 69: 45-51.

Steyn EMA. 1974b. Abscission of leaves in Greyia Hook. & Harv. – J. South Afr. Bot. 40: 193-200.

Steyn EMA. 1975. Embriogenie van Melianthus major L. – J. South Afr. Bot. 41: 199-205.

Steyn EMA, Wyk AE van. 1987. Floral development of Greyia flanaganii with notes on inflorescence initiation and sympodial branching. – South Afr. J. Bot. 53: 194-201.

Steyn EMA, Robbertse PJ, Schijff HP van der. 1986. An embryogenetic study of Bersama transvaalensis and Greyia sutherlandii. – South Afr. J. Bot. 52: 25-29.

Steyn EMA, Robbertse PJ, Wyk AE van. 1987. Floral development in Greyia flanaganii with notes on inflorescence initiation and sympodial branching. – South Afr. J. Bot. 53: 194-201.

Struck M. 1997. Floral divergence and convergence in the genus Pelargonium (Geraniaceae) in southern Africa: ecological and evolutionary considerations. – Plant Syst. Evol. 208: 71-97.

Struck M, Walt JJA van der. 1996. Floral structure and pollination in Pelargonium. – In: Maesen LJG van der, Burgt XM van der, Medenbach de Rooy JM van (eds), The biodiversity of African plants, Kluwer Academic, The Hague, pp. 631-638.

Touloumenidou T, Bakker FT, Albers F. 2007. The phylogeny of Monsonia L. (Geraniaceae). – Plant Syst. Evol. 264: 1-14.

Tsevegsuren N, Aitzetmüller K, Vosmann K. 2004. Geranium sanguineum (Geraniaceae) seed oil: a new source of petroselinic and vernolic acid. – Lipids 39: 571-576.

Tutel B. 1984. Comparison on the taxonomy and leaf anatomy of the genus Biebersteinia with the other genera of Geraniaceae in Turkey. – Istanbul Univ. Fen Fak. Mecm., B, 47-48: 51-87.

Umadevi I, Daniel M, Sabnis SD. 1986. Interrelationships among the families Aceraceae, Hippocastanaceae, Melianthaceae, Staphyleaceae. – J. Plant Anat. Morph. 3: 169-172.

Venter HJT. 1979. A monograph of Monsonia L. (Geraniaceae). – Meded. Landbouwh. Wageningen 79: 1-128.

Venter HJT. 1983. Phytogeography and interspecies relationships in Monsonia L. (Geraniaceae). – Bothalia 14: 865-869.

Venter HJT. 1990. An account of Monsonia. – In: Vorster P (ed), Proc. 1st International Geraniaceae Symposium, University of Stellenbosch, Republic of South Africa, pp. 331-351.

Verdcourt B. 1950. Notes on the genus Bersama in Africa. – Kew Bull. 1950: 233-244.

Verdcourt B. 1958. Melianthaceae. – In: Hubbard CE, Milne-Redhead E (eds), Flora of tropical East Africa, Crown Agents for Oversea Governments and Administrations, London, pp. 1-7.

Verhoeven RL, Marais EM. 1990. Pollen morphology of the Geraniaceae. – In: Vorster P (ed), Proceedings of the 1st International Geraniaceae Symposium, University of Stellenbosch, Republic of South Africa, pp. 137-173.

Verhoeven RL, Venter HJT. 1986. Pollen morphology of Monsonia. – South Afr. J. Bot. 52: 361-368.

Vorster P (ed). 1990. Proceedings of the 1st International Geraniaceae Symposium held at the University of Stellenbosch, Republic of South Africa. – Stellenbosch.

Vorster P, Gilbert MG. 1993. Pelargonium wonchiense (Geraniaceae): a new species from Ethiopia. – Nord. J. Bot. 13: 395-398.

Walt JJA van der. 1977. Pelargoniums of Southern Africa 1. – Purnell, Cape Town.

Walt JJA van der, Vorster PJ. 1981. Pelargoniums of Southern Africa 2. – Juta, Cape Town.

Walt JJA van der, Vorster PJ. 1983. Phytogeography of Pelargonium. – Bothalia 14: 517-523.

Walt JJA van der, Vorster PJ. 1988. Pelargoniums of Southern Africa 3. – National Botanical Gardens, Kirstenbosch, Cape Town.

Walt JJA van der, Werker E, Fahn A. 1987. Wood anatomy of Pelargonium (Geraniaceae). – IAWA Bull., N. S., 8: 95-108.

Walt JJA van der, McDonald DJ, Wik N van. 1990. A new species of Pelargonium with notes on its ecology and pollination biology. – South Afr. J. Bot. 56: 467-470.

Warburg EF. 1938. Taxonomy and relationships in the Geraniales in the light of their cytology. – New Phytol. 37: 130-159, 189-210.

Weber M. 1996. The existence of a special exine coating in Geranium robertianum pollen. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 157: 195-202.

Weigend M. 2005. Notes on the floral morphology in Vivianiaceae (Geraniales). – Plant Syst. Evol. 253: 125-131.

Weigend M. 2006. Ledocarpaceae. – In: Kubitzki K (ed), The families and genera of vascular plants IX. Flowering plants. Eudicots. Berberidopsidales, Buxales, Crossosomatales, Fabales p. p., Geraniales, Gunnerales, Myrtales p. p., Proteales, Saxifragales, Vitales, Zygophyllales, Clusiaceae Alliance, Passifloraceae Alliance, Dilleniaceae, Huaceae, Picramniaceae, Sabiaceae, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 213-220.

Weigend M. 2011. The genus Balbisia (Vivianiaceae, Geraniales) in Peru, Bolivia and northern Chile. – Phytotaxa 22: 47-56.

Weng M-L, Ruhlman TA, Gibby M, Jansen RK. 2012. Phylogeny, rate variation, and genome size evolution of Pelargonium (Geraniaceae). – Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 64: 654-670.

Weng M-L, Blazier JC, Govindu M. Jansen RK. 2014. Reconstruction of the ancestral plastid genome in Geraniaceae reveals a correlation between genome rearrangements, repeats and nucleotide substitution rates. – Mol. Biol. Evol. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst257

White F. 1966. 57. Melianthaceae. – In: Exell AW, Fernandes A, Wild H (eds), Flora Zambesiaca 2 (Part 2), Crown Agents for Oversea Governments and Administrations, London, pp. 544-547.

Williams CA, Newman M, Gibby M. 2000. The application of leaf phenolic evidence for systematic studies within the genus Pelargonium (Geraniaceae). – Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 28: 119-132.

Willson MF, Miller LJ, Rathcke BJ. 1979. Floral display in Phlox and Geranium: adaptative aspects. – Evolution 33: 52-63.

Xifreda CC. 1973. Anatomia foliar de Wendtia y Balbisia (Geraniaceae). – Kurtziana 7: 213-232.

Yeo PF. 1969. Two new Geranium species endemic to Madeira. – Bol. Mus. Munic. Funchal 23: 25-35.

Yeo PF. 1973. The biology and systematics of Geranium, sections Anemonifolia Knuth and Ruberta Dum. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 67: 285-346.

Yeo PF. 1984. Fruit-discharge-type in Geranium (Geraniaceae): its use in classification and its evolutionary implications. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 89: 1-36.

Yeo PF. 1990. The classification of Geraniaceae. – In: Vorster P (ed), Proceedings of the 1st International Geraniaceae Symposium, University of Stellenbosch, Republic of South Africa, pp. 1-22.

Yeo PF. 2004. The morphology and affinities of Geranium sections Lucida and Unguiculata. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 144: 409-429.