SAPINDANAE Doweld

Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.: xxxiv. 23 Dec

2001

Rutanae Takht., Sist.

Filog. Cvetk. Rast. [Syst. Phylog. Magnolioph.]: 311. 4 Feb 1967, nom.

illeg.; Rutidae Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant.

Vasc.: xxxiii. 23 Dec 2001; Rutineae Doweld ex Reveal

in Kew Bull. 66: 48. Mar 2011

[Sapindales+[Huerteales+[Capparales+Malvales]]]

SAPINDALES Juss. ex Bercht. et

J. Presl

Berchtold et Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 224. Jan-Apr

1820 [‘Sapindeae’]

Fossils Chaneya, from

the Cenozoic of North America, Europe and Asia, is represented by flowers and

winged fruits. It may be assigned to some group of Sapindales.

Habit Bisexual, monoecious,

andromonoecious, polygamomonoecious, dioecious, androdioecious, gynodioecious,

or polygamodioecious (sometimes morphologically bisexual and functionally

monoecious), evergreen or deciduous trees, shrubs or lianas (sometimes

perennial or annual herbs).

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

ab initio usually superficial (sometimes cortical or pericyclic; sometimes

absent). Secondary lateral growth normal or anomalous (from concentric cambia).

Vessels usually solitary and in radial multiples. Vessel elements usually with

simple (rarely scalariform or reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits

usually alternate (rarely opposite or scalariform), simple or bordered pits.

Vestured pits sometimes present. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements usually

libriform fibres (sometimes fibre tracheids) with usually simple (sometimes

bordered) pits, septate or non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays

uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular, or absent. Axial

parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates, or paratracheal

scanty, aliform, lozenge-aliform, winged-aliform, confluent, vasicentric, or

banded, or absent. Secondary phloem sometimes stratified into hard fibrous and

soft parenchymatous layers. Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes usually 3:3,

trilacunar with three leaf traces, or 5:5, pentalacunar with five traces

(sometimes 1:1, unilacunar with one trace, rarely heptalacunar). Laticifers

with latex or resinous substances sometimes present; resinous cells sometimes

frequent. Sclereids often present in cortex. Parenchyma sometimes with mucilage

cells, often having swollen and layered inner periclinal walls, or with

secretory cavities and ducts containing ethereal oils. Wood often silicified or

with silica bodies. Calciumoxalate as prismatic crystals or druses.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or

multicellular, uniseriate or multiseriate, simple, furcate, stellate or

lepidote (sometimes complex capitate); glandular hairs multicellular (sometimes

peltate-lepidote; helical glands sometimes frequent).

Leaves Usually alternate

(spiral; sometimes opposite, rarely verticillate), usually pinnately or

palmately compound (sometimes bipinnate or unifoliolate, or simple and entire

or lobed), with conduplicate, supervolute or plicate (sometimes curved or flat)

ptyxis. Stipules usually absent (sometimes petiolar, rarely intrapetiolar or

cauline); stipules possibly being modified leaflets (described as

pseudostipules or metastipules, having typical stipule morphology, although

probably being modified pseudostipules); leaf sheath absent. Colleters often

abundant. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate or annular; petiole

sometimes with cortical or adaxial bundles (sometimes wing bundles). Venation

usually pinnate (sometimes palmate), brochidodromous, eucamptodromous, or

craspedodromous. Stomata usually anomocytic, paracytic (sometimes cyclocytic,

tetracytic, actinocytic or parallelocytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids usually

absent (rarely as tubuli). Domatia present as pits, pockets or hair tufts, or

absent. Lamina often gland dotted, usually without secretory cavities

(sometimes with lysigenous or schizogenous cavities and canals containing

resins or ethereal oils). Epidermis usually with mucilaginous idioblasts.

Mesophyll with or without spherical idioblasts containing ethereal oils, with

or without mucilaginous idioblasts, with or without sclerenchymatous

idioblasts. Mesophyll cells often with calciumoxalate druses or prismatic

crystals. Leaf margin and leaflet margins entire, crenate, or serrate. Leaf

teeth, when present, with transparent glandular tip, distally expanding and

with foramen and two accessory veins (or one vein, second vein running above

tooth).

Inflorescence Terminal or

axillary, panicle, thyrsoid, dichasial, raceme- or umbel-like, thyrse, raceme,

spike or head (rarely solitary axillary). Floral prophylls (bracteoles) rarely

absent.

Flowers Usually actinomorphic

(rarely zygomorphic). Usually hypogyny (occasionally epigyny). Sepals (two or)

four or five (to eight), usually with imbricate, valvate or induplicate-valvate

(rarely open) aestivation, free or connate in lower part (rarely absent).

Petals (two or) four or five (to 14), usually with imbricate or valvate

(sometimes induplicate-valvate or contorted) aestivation, often clawed and/or

with scale-like or other appendages or folds enclosing nectaries, usually free

(rarely connate at base; sometimes absent). Nectariferous disc extrastaminal or

intrastaminal, annular or unilateral (sometimes lobate or reduced to glandular

teeth), or nectariferous glands extrastaminal, alternipetalous, and disc

absent.

Androecium Stamens (three or)

five, 3+3, 4+4 or 5+5 (to 18) in one to three (to five) whorls, usually haplo-,

diplo- or obdiplostemonous. Filaments usually free from each other and from

tepals (sometimes more or less connate, sometimes connate into tube), sometimes

articulated. Anthers usually dorsifixed (sometimes basifixed), usually

versatile, tetrasporangiate, usually introrse (rarely extrorse or latrorse),

longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory. Staminodia one

to ten, extrastaminal or intrastaminal, or absent; female flowers often with

staminodia.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually triporate, 2–4-colpate

or 2–5(–8)-colpor(oid)ate (sometimes acolpate, syncolporate or

parasyncolporate, rarely polyporate or rugate), usually shed as monads (rarely

tetrads), usually bicellular (sometimes tricellular) at dispersal. Exine

tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, reticulate,

microreticulate, rugulate, scabrate, striate, gemmate, spinulate or psilate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

(two or) three to five (to 20) connate eusyncarpous antepetalous carpels, or

carpels secondarily free (apocarpy); odd carpel usually adaxial. Ovary usually

superior (rarely inferior), unilocular to quinquelocular (to 20-locular;

sometimes pseudomonomerous). Style single, simple or lobate (sometimes hollow),

or stylodia two to six, free or connate in lower part, or absent. Stigma one,

capitate, clavate, peltate or lobate, or stigmas two to five, punctate, usually

non-papillate, Dry or Wet type. Male flowers often with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation axile,

apical, basal, or parietal. Ovules usually one or two (sometimes three to

numerous) per carpel, usually anatropous or campylotropous (sometimes

hemianatropous or amphitropous, rarely orthotropous), ascending, horizontal or

pendulous, apotropous or epitropous, usually bitegmic (sometimes unitegmic),

crassinucellar. Micropyle bistomal or endostomal. Placental obturator sometimes

present. Archespore sometimes multicellular. Nucellar cap sometimes present.

Megagametophyte usually monosporous, Polygonum type (rarely

tetrasporous, 16-nucleate, 13-celled, Penaea type). Synergids

sometimes with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells sometimes proliferating

(up to 14 cells), rarely persistent. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear.

Endosperm haustoria chalazal or absent. Embryogenesis asterad, solanad or

onagrad.

Fruit Usually a loculicidal

(sometimes septicidal, septifragal or irregularly dehiscent) capsule or a drupe

(sometimes a berry, samara, follicle, pyxidium, nut, hesperidium, syncarp, or

schizocarp with nutlike, samaroid, berry-like or drupaceous mericarps).

Seeds Aril usually absent.

Arillode, sarcotesta or elaiosome sometimes present. Testa often vascularized

(sometimes collapsed). Exotesta often palisade, lignified or non-lignified.

Mestotesta sometimes sclerotic or lignified. Endotesta sometimes with stellate

calciumoxalate crystals, sometimes lignified and tracheidal. Exotegmen often

lignified or fibrous, sometimes tracheidal, or crushed. Endotegmen sometimes

thickened and lignified (rarely tracheidal or fibrous), or crushed. Perisperm

not developed. Endosperm usually sparse or absent (rarely copious). Embryo

usually curved to spirally twisted (sometimes straight), usually well

differentiated, often large, oily, proteinaceous or often starchy, with or

without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar or

cryptocotylar.

Cytology x = 5–13

DNA Plastid gene infA

lost/defunct. Mitochondrial intron coxII.i3 lost.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), flavones, biflavones, flavone methyleters,

biflavonyls, 5-deoxyflavonoids, cyanidin, delphinidin, monoterpenes,

triterpenes, tetranor- and pentanortriterpenes, triterpenoid bitter substances

(meliacins, limonoids, simaroubalides-quassinoids), ethereal oils

(monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, phenylpropans), ellagic acid (rare),

hydrolyzable and non-hydrolyzable tannins, phenols with unsaturated

side-chains, acridines, β-carbaline alkaloids, imidazole, quinoline alkaloids,

benzylisoquinoline alkaloids, anthranilic-derived alkaloids, toxic triterpene

saponins, pentacyclic terpene saponins, leucine- or phenylalanine-derived

cyanogenic compounds, polyacetate- or shikimic acid-derived arthroquinones,

pyranochromones, coumarins, furanocoumarins, quebrachitol (cyclitol), ethereal

oils with high content of aliphatic carbohydrates, polyacetylenes, cyclic

polyvalent alcohols, amides, type C18:3 fatty acids, cyclopropane

amino acids, and polygalitol present.

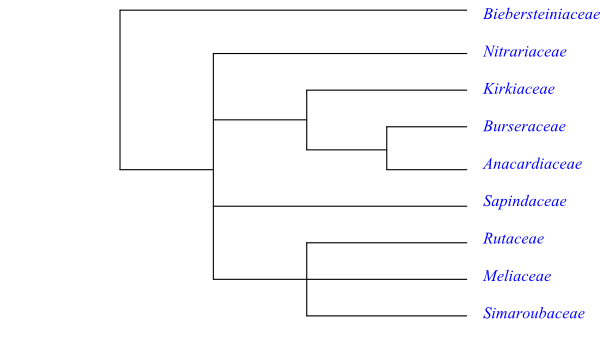

Systematics Sapindales may be sister-group to

the clade [Huerteales+[Capparales+Malvales]].

The sister-group relationships in Sapindales are only partly

resolved and several clades are only weakly supported.

According to Stevens (2001 onwards) Sapindales except

Biebersteinia (Biebersteiniaceae) are

supported by the synapomorphy: stigma papillate, stigmatic head arising from

postgenitally fused free carpellary apices. There is weak support from

molecular data for Nitrariaceae being sister to the

remaining Sapindales

(except Biebersteinia). The following potential synapomorphies are

suggested by Stevens (2001 onwards): remnants of floral apex persisting in

centre of gynoecium; ovules two per carpel, epitropous, superposed; micropyle

endostomal (inner integument elongated), S- or Z-shaped; and presence of

nucellar cap. The clade [Kirkiaceae+[Burseraceae+Anacar-diaceae]]

is usually well supported and has the following synapomorphies: inflorescence

thyrsoid (panicle consisting of cymes); carpels adnate to central receptacular

apex, synascidiate; stigma with uniseriate multicellular papillae, Wet type;

fruits containing one seed per carpel; and endocarp well developed. Finally,

Anacardiaceae and Burseraceae share the following

characters: phloem with vertical intercellular secretory resinous ducts, and

surrounded by light-coloured, sinuous sclerenchymatous band; glandular hairs

with uniseriate stalk; absence (usually) of cuticular waxes; flowers fairly

small; sepals often connate; petals little longer than sepals; central

receptacular apex more or less exposed in floral centre; ovule pachychalazal;

fruit an operculate drupe; endocarp cells lignified and not orientated; and

presence of biflavonoids.

[Sapindaceae+[Simaroubaceae+[Meliaceae+Rutaceae]]] is a clade with

relatively low support in molecular analyses. Muellner-Riehl & al. (2016)

present the following topology (Maximum Likelihood): [Sapindaceae+[Rutaceae+[Simaroubaceae+Meliaceae]]]. Stevens (2001

onwards) lists the following potential synapomorphies: anthers with pseudo-pit;

tapetal cells multinucleate, nuclei fusing to form polyploid mass; presence of

hypostase; and testa multiplicative and more than five cell layers thick. The

clade [Simaroubaceae+Rutaceae+Meliaceae] has the following

characters in common: absence of cuticular waxes; inflorescence branches

cymose; and presence of alkaloids and bitter-tasting pentanortriterpenes

(limonoids, protolimonoids, meliacins, cneorids, quassinoids, etc. – all

triterpenoids – are closely related biosynthetically). Moreover, Meliaceae and Rutaceae share the potential

synapomorphies: capitate stigma; and presence of flavones and

tetranortriterpenes (bitter-tasting).

Brown in J. H. Tuckey, Narr. Exped. Zaire: 431. 5

Mar 1818 [‘Cassuviae (or Anacardeae)’], nom. cons.

Terebinthaceae Juss.,

Gen. Plant.: 368. 4 Aug 1789 [’Terebintaceae’], nom. illeg.;

Cassuviaceae Juss. ex R. Br. in J. H. Tuckey, Narr.

Exped. Zaire: 431. 5 Mar 1818 [‘Cassuviae (or

Anacardeae)’], nom. illeg.; Comocladiaceae

Martinov, Tekhno-Bot. Slovar: 144. 3 Aug 1820 [‘Comocladieae’];

Pistaciaceae Martinov, Tekhno-Bot. Slovar: 485. 3 Aug

1820 [‘Pistaceae’]; Spondiadaceae

Martinov, Tekhno-Bot. Slovar: 594. 3 Aug 1820 [‘Spondiaceae’];

Terebinthales Juss. ex Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir.

Rostlin: 228. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Terebinthaceae’], nom. illeg.;

Rhoaceae Spreng. ex J. Sadler, Fl. Comit. Pest. 2:

135. 30 Mai 1826 [‘Therebinthaceae, Rhoes Spr.,

Dumosae L.’]; Anacardiineae Link, Handbuch

2: 124. 4-11 Jul 1829 [‘Anacardiaceae’];

Spondiadineae Link, Handbuch 2: 126. 4-11 Jul 1829

[‘Spondiaceae’]; Terebinthopsida Bartl.,

Ord. Nat. Pl.: 229, 382. Sep 1830 [’Terebinthinae’], nom. illeg.;

Vernicaceae Schultz Sch., Nat. Syst. Pflanzenr.: 488.

30 Jan-10 Feb 1832 [’Verniceae’];

Cassuviales R. Br. in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp.

Regn. Veg.: 41. Sep-Oct 1835 [‘Cassuvieae’], nom. illeg.;

Spondiadales Kunth in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp.

Regn. Veg.: 56. Sep-Oct 1835 [‘Spondiaceae’];

Schinaceae Raf., Fl. Tellur. 3: 55. Nov-Dec 1837

[‘Schinidia’]; Sumachiaceae DC. ex

Perleb, Clav. Class.: 31. Jan-Mar 1838 [’Sumachineae’], nom.

illeg.; Lentiscaceae Horan., Tetractys: 25. Jun-Dec

1843 [‘Lentiscaceae (Pistaceae Link et Mart.)’];

Podoaceae Baill. ex Franch., Pl. Delav.: 145. Mai

1889 [‘Podoonaceae’]; Julianaceae Hemsl.

in J. Bot. 44: 379. Oct 1906 [‘Julianiaceae’], nom. cons.;

Julianales Engl., Syllabus, ed. 5: 111. Jul 1907

[‘Julianiales’]; Blepharocaryaceae Airy

Shaw in Kew Bull. 18: 254. 8 Dec 1965

Genera/species 77/830–875

Distribution Mainly tropical

and subtropical regions in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres; some species

in warm-temperate areas north to southern Canada, Central and East Europe, and

northeastern China.

Fossils Fruits are found in

the Early Eocene of North America and England, and Paleogene wood has been

attributed to Anacardiaceae.

Habit Monoecious,

andromonoecious, polygamomonoecious, dioecious, or gynodioecious (sometimes

bisexual), evergreen or deciduous trees or shrubs (sometimes with spines;

rarely lianas or perennial herbs to suffrutices).

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

ab initio usually superficial (sometimes cortical). Medulla loose, shining.

Primary medullary rays narrow or wide. Vessel elements usually with simple

(rarely scalariform or reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits alternate,

simple pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform fibres with simple

or bordered pits, septate or non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood

rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial

parenchyma usually paratracheal scanty, aliform, vasicentric, or banded

(sometimes absent). Wood often fluorescent. Tyloses often frequent. Sieve tube

plastids S type. Nodes usually 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces (rarely

unilacunar or 5:5, pentalacunar with five traces). Phloem with vertical

intercellular secretory ducts and surrounded by pale sinuous sclerenchymatous

band. Bark in many species with laticifers or vertical resinous ducts with

black, red to yellow, white or colour-less exudate. Wood often silicified or

with silica grains. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals frequent.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or

multicellular, uniseriate; stellate or peltate-lepidote glandular hairs often

present.

Leaves Usually alternate

(spiral; in, e.g., Bouea and Blepharocarya opposite, rarely

verticillate), trifoliolate or imparipinnate (sometimes unifoliolate, or simple

and entire or lobed; rarely palmate bipinnately compound), with conduplicate?

ptyxis. Stipules absent; leaf sheath absent. Petiole base often pulvinate.

Petiole vascular bundle transection?; petiole with cylinder of wing bundles.

Petiole base often swollen. Distal part of petiole sometimes with paired

extrafloral nectaries. Petiolules not articulated. Venation usually pinnate

(sometimes palmate). Stomata anomocytic, paracytic, cyclocytic, tetracytic or

parallelocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids as clustered tubuli

(Berberis type), chemically dominated by nonacosan-10-ol. Domatia as

pits, pockets or hair tufts. Larger leaf veins and petiole phloem with usually

lysigenous (rarely schizogenous) secretory cavities and ducts containing resin,

balsam or latex. Mesophyll cells sometimes with calciumoxalate druses. Leaf

margin and leaflet margins serrate, crenate or entire. Extrafloral nectaries

sometimes present on stipules, petiole and lamina (e.g. in Anacardium

and Holigarna).

Inflorescence Terminal or

axillary, panicle, thyrsoid or raceme- or spike-like (flowers rarely solitary).

Extrafloral nectaries present on bracts in, e.g., Holigarna.

Flowers Usually actinomorphic

(rarely zygomorphic), small. Pedicel often articulated (in Anacardium

accrescent and swollen in fruit). Hypanthium sometimes present. Usually

hypogyny (in Drimycarpus and Holigarna epigyny). Sepals

(three or) four or five (to eight), with imbricate or valvate aestivation,

usually connate in lower part (sometimes absent), persistent or caducous,

sometimes accrescent in fruit. Petals (three or) four or five (to eight), with

imbricate or valvate (rarely open) aestivation, usually free (rarely connate at

base; sometimes absent), persistent (rarely accrescent) in fruit or caducous.

Nectariferous disc usually intrastaminal (in Mangifera extrastaminal),

usually annular (sometimes quinquelobate or modified into androphore or

gynophore, or absent). Floral tissues usually resiniferous.

Androecium Stamens usually

five, haplostemonous, antesepalous, alternipetalous, or 5+5, diplostemonous

(rarely one, in Anacardium, to four, 4+4, or more than ten to more

than 100). Filaments usually free (rarely connate at base), free from tepals,

sometimes inserted on nectariferous disc. Anthers usually dorsifixed (sometimes

basifixed), versatile, tetrasporangiate, usually introrse (rarely extrorse or

latrorse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory,

often with at least binucleate cells. Staminodia one to nine or absent; female

flowers often with staminodia.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually (2–)3(–8)-colporate

(rarely colpate, rugate or polyporate), shed as monads, bicellular at

dispersal. Exine semitectate, with columellate infratectum, reticulate or

microreticulate to striate or striate-reticulate.

Gynoecium Carpels usually one

to five (rarely up to 13 [Pleiogynium]), usually connate (rarely free

in upper part; often only one carpel fertile leading to pseudomonomery). Ovary

usually superior (rarely inferior), usually bilocular to quinquelocular (rarely

up to 13-locular; often only a single locule fertile: pseudomonomerous), or

unilocular (monomerous). Style single, simple, or stylodia three to five

(rarely up to 13; sometimes gynobasic), connate in upper parts. Stigma(s) one

to five, usually capitate (sometimes discoid, spatulate or lobate, rarely

punctate), non-papillate, Dry type. Male flowers sometimes with

pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation apical to

axile or basal (when ovary multilocular), or parietal to basal (when ovary

unilocular). Ovule one per fertile carpel, usually anatropous (rarely

hemianatropous), ascending or pendulous, usually apotropous (sometimes

epitropous), unitegmic or bitegmic, crassinucellar. Funicle often long.

Micropyle usually bistomal, Z-shaped (zig-zag; sometimes endostomal). Outer

integument ? cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Hypostase

present or absent. Often with a placental obturator, ponticulus, at funicular

base. Nucellar beak absent. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum

type. Synergids hooked. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm

haustoria? Embryogenesis usually onagrad (sometimes asterad, Penaea or

Euphorbia type) Polyembryony occurring in several species. Chalazogamy

present in many species (pollen tube growing via ponticulus to chalaza).

Fruit Usually a drupe, often

asymmetrical, often operculate, flattened, sometimes with accrescent calyx

(sometimes a samara; rarely with accrescent corolla; rarely a berry- or nutlike

fruit, or a syncarp; fruits in Blepharocarya adnate to cupule-like

lignified inflorescence branches; fruit in Amphipterygium attached to

wing-like flat peduncle). Mesocarp sometimes with black resins. Endocarp often

consisting of unorientated sclerified and crystalliferous cells.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed often

pachychalazal. Seed coat usually reduced. Exotestal cells (and hypodermis)

sometimes thickened. Endotesta? Exotegmen? Endotegmen usually thickened, with

lignified cell walls. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm sparse, with oil and

sometimes starch, or absent. Embryo usually curved (sometimes straight, rarely

hippocrepomorphic), usually well differentiated, oily, with or without

chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, in e.g. Mangifera folded. Germination

phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = 7–12, 14–16,

21

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), biflavones, biflavonyls, 5-deoxyflavonoids,

cyanidin, delphinidin, balsams containing mono- and triterpenes, hydrolyzable

and condensed tannins, often extremely allergenic phenols with unsaturated

side-chains and cyclic polyvalent alcohols and their derivatives, often very

toxic and dermatitis-causing resins (e.g. campnospermonol, catechols,

resorcinols, anacardic acid, cardanol, cardol, and urushiol), triterpene

saponins and polyacetate-derived arthroquinones present. Ellagic acid and

cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Ornamental plants, fruits

(Anacardium occidentale, Magnifera indica, Pistacia

vera, Schinus, Semecarpus, Spondias, etc.),

spices, terpentine, lacquer, resins, tannins, oils, varnish (Pistacia,

‘Rhus’ s.l., Toxicodendron), timber.

Systematics (under

construction) Anacardiaceae are sister to

Burseraceae.

Pegia and the doubtfully monophyletic

Spondias appear to form a sister-group (here Spondiadoideae

s.str.) to the remaining Anacardiaceae (Pell 2004).

Spondiadoideae Kunth

ex Arn., Botany: 106. 9 Mar 1832 [‘Spondiaceae’]

4/>20.

Haplospondias (1; H. brandisiana; Yunnan,

Burma),Pegia (2; P. nitida, P. sarmentosa; eastern

Himalayas, East Asia, West Malesia), Spondias (>16; Madagascar,

tropical Asia to tropical China and Indochina, islands in southern Pacific,

tropical America; monophyletic?), Poupartiopsis (1; P.

spondiocarpus; eastern Madagascar). – Madagascar, tropical Asia to West

Malesia, tropical America. Trees or lianas. Stamens eight or ten. Nectariferous

disc intrastaminal. Ovary quadrilocular or quinquelocular. Style one, simple,

or stylidia four or five, connate above. Fruit a drupe. Endocarp consisting of

unorientated sclerified cells and crystalliferous cells.

Anacardioideae Arn.,

Botany: 106. 9 Mar 1832 [’Anacardiaceae’]

Tapirireae Marchand,

Rév. Anacardiac.: 161. Jan–Jun 1869 [‘Tapirieae’]

10/85–90. Choerospondias (1;

C. axillaris; northeastern India to northern Thailand, Vietnam,

southeastern China, Taiwan and Japan), Cyrtocarpa (5; C.

caatingae, C. edulis, C. kruseana, C. procera,

C. velutinifolia; southern Baja California, western Mexico, northern

Colombia to Guyana, Venezuela and northern Brazil, the Caatinga in northeastern

Brazil), Pleiogynium (2; P. solandri, P. timoriense;

Indochina and Malesia to Queensland and islands in the Pacific),

Dracontomelon (8; Southeast Asia, Malesia to Fiji), Tapirira

(8–10; tropical America), Antrocaryon (4; A. klaineanum,

A. micraster, A. nannanii, A. schorkopfii;

tropical Africa, tropical South America), Poupartia (c 10; Madagascar,

the Mascarene Islands), Harpephyllum (1; H. caffrum; southern

Africa), Lannea (c 40; tropical Africa, Madagascar, Socotra, tropical

Asia), Operculicarya

(8; Madagascar, the Comoros, Aldabra). – Pantropical. Stamens

obdiplostemonous. Pistil composed of (one to) four or five (to twelve) connate

carpels. Ovary (1–)4–5(–12)-locular. When locule single, then ovary

possibly pseudomonomerous. Placentation apical. Ovules usually one (sometimes

two) per carpel, pendulous (when two then one ovule epitropous). Hypostase

present. Funicle massive. Exocarp thick, with or without operculum. Endocarp

consisting of unorientated sclerified cells and crystalliferous cells.

Exotestal cells thickened or not, persistent. Tegmen often absent. Hypostase

persistent, saddle-shaped. Biflavonoids present. Alkylcathechols and

alkylresorcinols absent.

Buchananieae Marchand,

Rév. Anacardiac.: 191. Jan-Jun 1869

3/43–50. Buchanania (25–30;

tropical Asia to islands in western Pacific), Campnosperma (>13;

Madagascar, the Seychelles, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea,

islands in western Pacific, tropical America), Pentaspadon (5; P.

annamensis, P. curtisii, P. motleyi, P.

poilanei, P. velutinus; Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea,

Solomon Islands). – Madagascar, the Seychelles, tropical Asia to western

Pacific, tropical America. Pistil in Buchanania composed of six

partially connate carpels. – Buchanania is sister to the remaining

Anacardioideae (except the Lannea clade) in several analyses.

They differ from Anacardieae in the number of carpels (four to six),

the position of the fertile carpel, the endocarp anatomy (endocarp consisting

of unorientated sclerified cells and crystalliferous cells), and

phytochemistry. Campnosperma and Pentaspadon have similar

endocarp and Campnosperma may have bilocular fruit.

Anacardieae DC.,

Prodr. 2: 62. Nov (med.) 1825

39/555–585. Mainly tropical, but also

temperate regions. Leaves sometimes opposite, usually simple (sometimes

compound). Stamens usually five or ten (sometimes one+staminodia, or numerous).

Filaments sometimes connate at base. Pistil composed of usually one or three

connate carpels; only antesepalous carpel fertile. Styles sometimes connate.

Placentation apical to basal. Ponticulus sometimes present. Exocarp thin, with

lignified epidermis. Endocarp stratified, with up to three layers of lignified

palisade sclereids; inside these crystalliferous layer. Seed coat

undifferentiated.

Clade 1

7/185–190. Faguetia (1;

F. falcata; eastern Madagascar), Semecarpus (70–75;

tropical Asia to tropical Australia, New Caledonia and Fiji),

Fegimanra (3; F. acuminatissima, F. africana, F.

afzelii; tropical West and Central Africa), Anacardium (11;

southern Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America),

Gluta (c 30; Madagascar, tropical Asia), Bouea (3; B.

macrophylla, B. oppositifolia, B. poilanei; Southeast

Asia, West Malesia), Mangifera

(c 70; tropical Asia to Solomon Islands). – Tropical Africa, Madagascar,

tropical Asia to New Caledonia and Fiji, tropical America.

Clade 2

22/280–300. Thyrsodium

(7–8; T. africanum, T. bolivianum, T. guianense,

T. herrerense, T. paraense, T. puberulum, T.

schomburgkianum, T. spruceanum; tropical South America),

Amphipterygium (4–5; A. adstringens, A.

amplifolium, A. glaucum, A. molle, A.

simplicifolium; western Mexico to northwestern Costa Rica),

Orthopterygium (1; O. huaucui; western Peru),

Loxopterygium (3; L. grisebachii, L. huasango,

L. sagotii; northern and southern tropical South America),

Astronium (11; southern Mexico, Central America, tropical South

America), Schinopsis (8; tropical South America), Bonetiella

(1; B. anomala; northern and central Mexico), Comocladia

(16–20; Mexico, Central America, the West Indies), Metopium (3;

M. brownei, M. toxiferum, M. venosa; Florida,

Mexico, the West Indies), Cotinus

(7; C. carranzae, C. chiangii, C. kanaka, C.

szechuanensis, C. coggygria: the Mediterranean to China; C.

nanus: northwestern Yunnan; C. obovatus: southeastern United

States), Mosquitoxylum (1; M. jamaicense; southern Mexico to

northwestern Ecuador, Jamaica; in Rhus?), Rhus

(35–40; temperate and subtropical regions on both hemispheres), Searsia

(110–115; the Mediterranean, tropical and subtropical Africa, Socotra, the

Middle East, the Arabian Peninsula, India, the Himalayas, Burma, southwestern

China), Baronia (1; B. taratana; Madagascar),

Malosma (1; M. laurina; southwestern California, Baja

California), Laurophyllus

(1; L. capensis; Western and Eastern Cape), Lithraea

(3; L. brasiliensis, L. caustica, L. molleoides;

South America), Schinus

(30–35; Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical and subtropical

South America), Pachycormus (1; P. discolor; Baja California

in northwestern Mexico), Pistacia

(12; the Mediterranean, Asia to Malesia, southern United States to Central

America), Actinocheita (1; A. filicina; south central

Mexico), Toxicodendron

(22; tropical and East Asia to New Guinea, North America, Central America to

Bolivia). – Temperate to tropical regions on both hemispheres. – ‘Rhus’

is polyphyletic and needs extensive investigations.

Clade 3

10/90–95. Dobinea (2; D.

delavayi, D. vulgaris; eastern Himalayas to southern China);

Loxostylis (1; L. alata; KwaZulu-Natal, Western and Eastern

Cape), Smodingium (1; S. argutum; South Africa, Swaziland,

Lesotho), Sorindeia (9; tropical Africa, Madagascar, the Mascarene

Islands), Mauria (10–15; Central America, the Andes),

Protorhus (1; P. longifolia; Namibia, South Africa,

Swaziland, Madagascar), Abrahamia (19; Madagascar), Heeria

(1; H. argentea; Western Cape), Ozoroa (c 40; Africa,

Yemen)?, Micronychia (6; M. acuminata, M. danguyana,

M. humberti, M. macrophylla, M. madagascariensis,

M. tsiramiramy; Madagascar). – Tropical and southern Africa,

Madagascar, the Mascarene Islands, the Arabian Peninsula, eastern Himalayas to

southern China, the Andes.

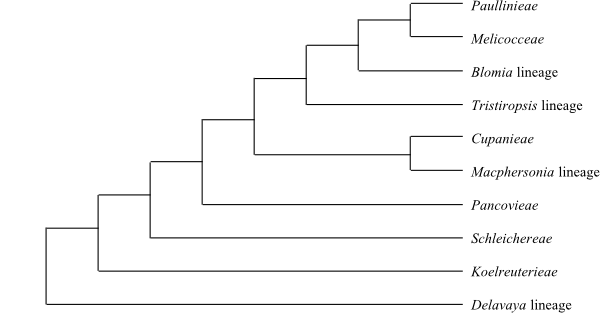

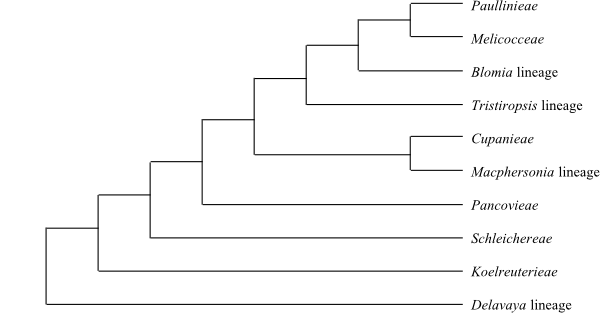

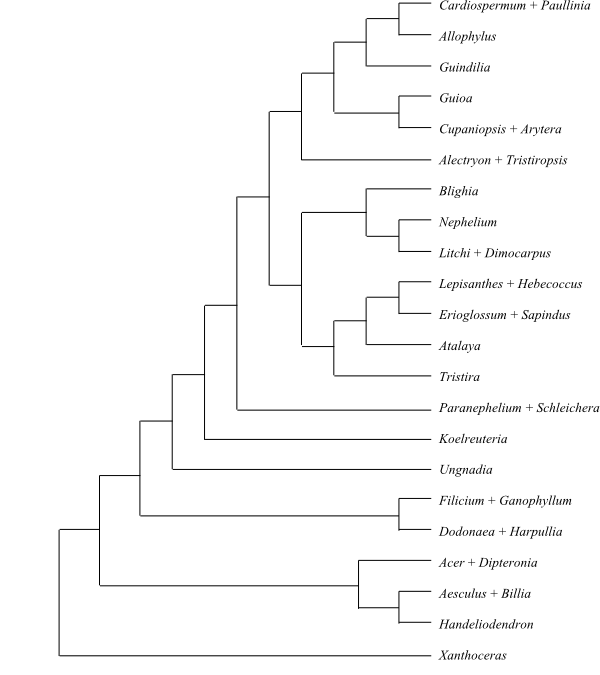

|

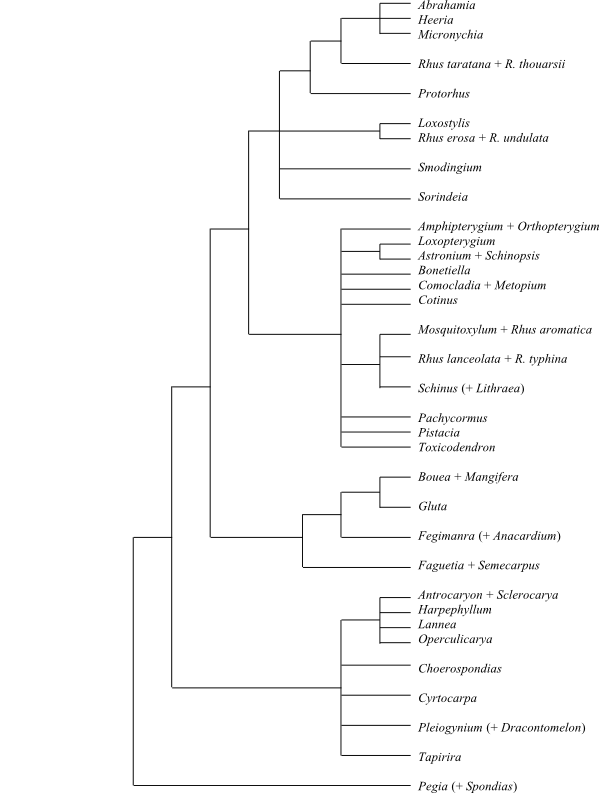

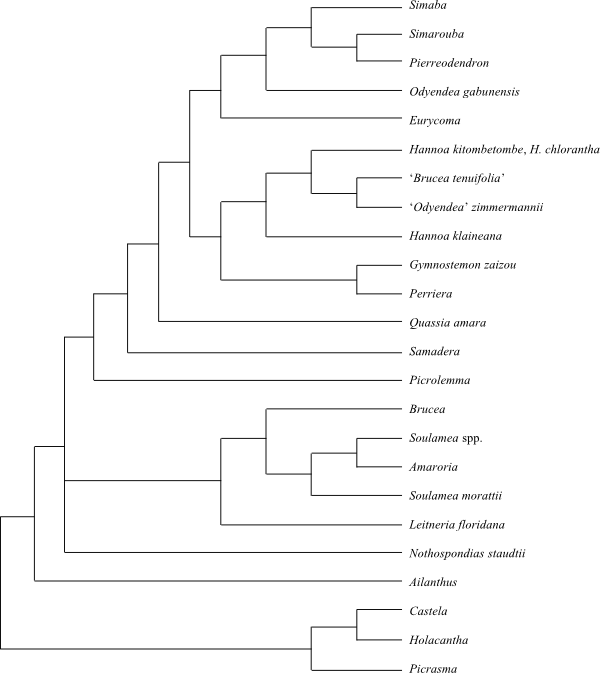

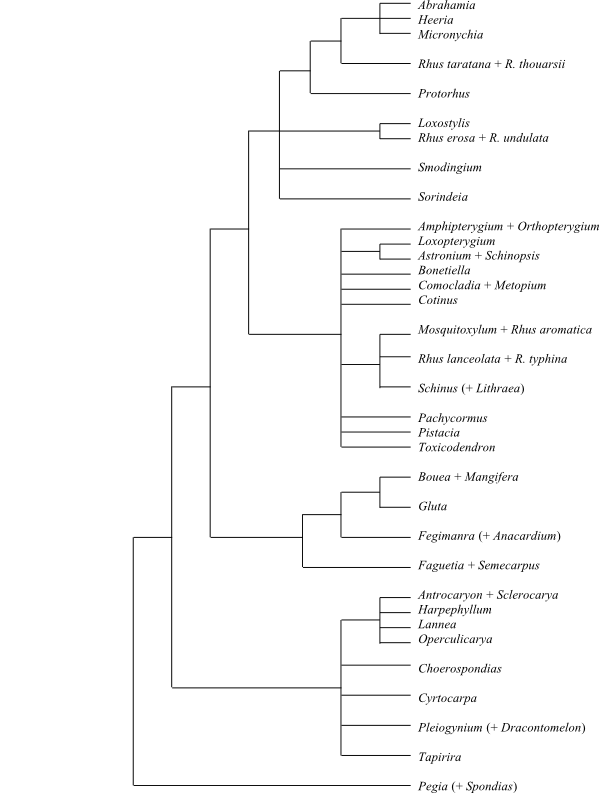

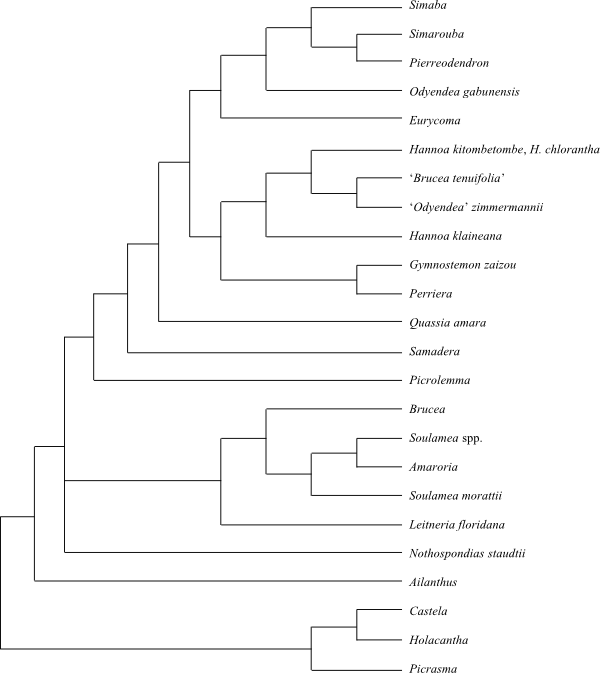

Bootstrap consensus tree of Anacardiaceae based on

DNA sequence data (Pell 2004).

|

Unplaced

Anacardioideae

Androtium (1; A.

astylum; West Malesia), Blepharocarya (2; B.

depauperata, B. involucrigera; Arnhem Land in Northern Territory,

northeastern Queensland), Campylopetalum (1; C. siamense;

Thailand), Cardenasiodendron (1; C. brachypterum; Bolivia),

Drimycarpus (3–4; D. anacardifolius, D. luridus,

D. maximus, D. racemosus; India to Borneo),

Euroschinus (>9; Malesia to New Guinea, eastern Queensland, eastern

New South Wales, New Caledonia), Haplorhus (1; H. peruviana;

the Andes in Peru and northern Chile), Melanochyla (c 30; southern

Thailand, Malesia), Nothopegia (>10; India, Sri Lanka),

Ochoterenaea (1; O. colombiana; Panamá, northern and central

Andes), Parishia (5; P. insignis, P. maingayi,

P. malabog, P. paucijuga, P. sericea; Burma,

Thailand, West Malesia), Pseudosmodingium (5; P. andrieuxii,

P. anomalum, P. barkleyi, P. multifolium, P.

perniciosum; Mexico), Rhodosphaera (1; R. rhodanthema;

southeastern Queensland, northeastern New South Wales), Swintonia (12;

the Andaman Islands, Southeast Asia, West and Central Malesia),

Trichoscypha (32; tropical and southern Africa).

Unplaced Anacardiaceae

Euleria (1; E.

tetramera; Cuba), Haematostaphis (1; H.

barteri; western tropical Africa to Nigeria), Hermogenodendron

(1; H. concinnum; Bahia and Espírito Santo in Brazil),

Holigarna (8; India, Southeast Asia), Koordersiodendron (1;

K. pinnatum; Borneo, the Philippines, Sulawesi, Maluku, New Guinea),

Pseudospondias (2; P. longifolia, P. microcarpa;

tropical West and Central Africa).

Schnizlein, Anal. Nat. Ordn. Gew.: 14. 1856

[‘Biebersteinieae’]

Biebersteiniales

Takht., Divers. Classif. Fl. Pl.: 327. 24 Apr 1997

Genera/species 1/5

Distribution Greece, Turkey,

the Caucasus and Iran to Central Asia and eastern Tibet.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, perennial

herbs with tuberous rhizome. Often evil-smelling.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

absent. Vessel elements with simple? perforation plates; lateral pits?

Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform fibres? Wood rays absent. Axial

parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids? Nodes? Crystals?

Trichomes Eglandular hairs

absent; glandular hairs with long multiseriate stalk and multicellular head.

Leaves Alternate (spiral), 2-

or 3-imparipinnate with lobed leaflets, or simple and pinnately lobed, with ?

ptyxis. Stipules petiolar, often lobed; leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular

bundle transection? Venation pinnate. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax

crystalloids? Leaflet margins serrate.

Inflorescence Terminal, erect

panicle or raceme.

Flowers Actinomorphic, large.

Hypogyny. Sepals five, with imbricate aestivation, persistent, free. Petals

five, with imbricate or contorted aestivation, often clawed, caducous, free.

Nectariferous glands extrastaminal, antesepalous, alternipetalous, fleshy

(staminodial?). Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens 5+5,

diplostemonous, antesepalous, alternipetalous, unequal in length. Filaments

connate at base, free from tepals. Anthers dorsifixed, versatile,

tetrasporangiate, introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits).

Tapetum secretory, with up to duodecemnucleate cells. Staminodia absent

(alternatively as extrastaminal nectariferous glands?).

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains dicolporate, shed as monads,

tricellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum,

striate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

five connate carpels. Ovary superior, deeply lobed, on short gynophore.

Stylodia five, compressed, gynobasic (inserted at base of ovary lobes), free in

lower part, connate at apex. Stigma capitate, type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation apical.

Ovule one per carpel, anatropous, pendulous, epitropous, unitegmic,

crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal. Integument four or five cell layers

thick. Funicle long, massive and irregularly bent. Obturator absent.

Megagametophyte tetrasporous, 16-nucleate, 13-celled, Penaea type.

Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A schizocarp with five

single-seeded nutlike mericarps, persistent central columella and accrescent

calyx.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa

thin-walled, more or less collapsed. Exotestal cells thick-walled,

non-lignified, non-fibrous, with sinuous anticlinal walls. Endotestal cells

polygonal, tanniniferous, with lignified walls. Perisperm not developed.

Endosperm sparse or absent. Suspensor absent. Embryo somewhat curved, well

differentiated, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two, foliaceous. Germination?

Cytology n = 5

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavone

methylethers, fatty acids of the type C18:3, and ethereal oils with

high content of aliphatic carbohydrates, alkaloids, bisabalone-type

sesquiterpene glycoside, myricetin, procyanidin and prodelphinidin present.

Ellagitannins and oxygenated sesquiterpenes not found.

Use Medicinal plants.

Systematics

Biebersteinia (5; B. emodii, B. heterostemon, B.

multifida, B. odora, B. orphanidis; Greece, Turkey, the

Caucasus and Iran to Central Asia, eastern Tibet and western Siberia).

Biebersteinia is sister to the

remaining Sapindales.

In Biebersteinia the pollen tube

reaches the apex of the megasporangium prior to micropyle formation

(pseudoporogamy; Yamamoto & al. 2014). The Penaea type of female

gametophyte is not known in other representatives of Sapindales (Kamelina & Konnova

1990).

Kunth in Ann. Sci. Nat. (Paris) 2: 346. Jul 1824,

nom. cons.

Balsameaceae Dumort.,

Anal. Fam. Plant.: 36, 41. 1829; Burserineae Link,

Handbuch 2: 127. 4-11 Jul 1829 [‘Burseraceae’];

Burserales Kunth in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp.

Regn. Veg.: 55. Sep-Oct 1835 [‘Burseraceae’];

Burseranae Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.: xxxiv.

23 Dec 2001

Genera/species 19/>765

Distribution Tropical and

subtropical regions on both hemispheres north to California, the Himalayas and

eastern China, and south to Uruguay, South Africa and northern Australia.

Fossils Fruits and seeds have

been found in Eocene layers in North America and Eocene fruits in England.

Habit Usually dioecious or

polygamomonoecious (sometimes bisexual), evergreen or deciduous trees or shrubs

(Bursera standleyana epiphytic). Branches usually spinose. Sometimes

pachycaul. Stilt roots or plank buttresses often present. Resin often fragrant

(often like almond).

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

usually superficial (in Santiria deeplier seated). Medulla often with

vascular strands. Vessel elements usually with simple (in Beiselia

scalariform) perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, bordered pits.

Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform fibres with simple or bordered

pits, usually septate. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or

heterocellular. Axial parenchyma usually paratracheal scanty vasicentric, or

absent. Tyloses often abundant. Secondary phloem sometimes stratified into hard

fibrous and soft parenchymatous layers. Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes

usually 5:5, pentalacunar with five leaf traces (sometimes multilacunar).

Phloem with vertical intercellular secretory ducts and surrounded by light

sinuous sclerenchymatous band. Schizogenous secretory cavities and canals with

white or uncoloured resinous exudate, aromatic (often almond-scented).

Sclereids present in stem cortex. Parenchyma often with mucilage cells. Wood

often silicified or with silica grains. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals

frequent.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or

multicellular, uniseriate, usually simple (sometimes furcate or stellate);

helical glands (spirally twisted, uniseriate glandular hairs) abundant.

Leaves Alternate (spiral),

usually imparipinnate (sometimes unifoliolate, rarely bipinnate or seemingly

trifoliolate), lobed, with conduplicate? ptyxis. Stipules usually absent

(rarely petiolar or cauline, laciniate to entire, possibly in reality reduced

basal leaflets); leaf sheath absent. Colleters often abundant. Stipule-like

leaflets or colleters often present. Petiole and petiolules often pulvinate.

Petiole vascular bundle transection usually annular (in Commiphora

arcuate); petiole sometimes with medullary rays. Leaf base often swollen,

adaxially concave. Venation pinnate. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax

crystalloids? Domatia as pits or hair tufts, or absent. Epidermis usually with

mucilage cells, sometimes with pellucid dots. Mesophyll with or without

mucilaginous idioblasts. Secretory cavities absent. Leaflet margins serrate or

entire.

Inflorescence Axillary,

thyrsoid, often raceme-, spike- or fascicle-like.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small.

Hypanthium present in, i.a., Garuga. Hypogyny. Sepals (three or) four

or five (to seven), with induplicate-valvate or imbricate (sometimes open)

aestivation, usually caducous (sometimes accrescent in fruit), usually connate

at base. Petals (three or) four or five (to seven), usually with

induplicate-valvate (in Boswellia and Canarium sometimes

imbricate) aestivation, usually free (sometimes connate at base; sometimes

absent). Nectariferous disc usually intrastaminal (in Aucoumea and

Triomma extrastaminal), usually annular or quinquepartite (sometimes

absent or as ovariodisc).

Androecium Stamens usually

3+3, 4+4 or 5+5, obdiplostemonous (sometimes three to five, haplostemonous,

alternisepalous, with antepetalous whorl absent; rarely antesepalous).

Filaments usually free from each other (in Canarium often more or less

connate), free from tepals. Anthers dorsifixed or basifixed, non-versatile or

somewhat versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse or latrorse, longicidal

(dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective sometimes slightly prolonged

apically. Tapetum secretory, with often binucleate cells. Female flowers often

with staminodia.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains 3(–6)-colporate, shed as

monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine semitectate, with columellate

infratectum, reticulate, microreticulate, often spinulate, sometimes striate or

psilate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

(two or) three to five (nine to twelve in Beiselia) connate carpels

(odd carpel in Amyris abaxial); symplicate zone of carpel well

developed; occasionally only one carpel developing. Ovary usually superior

(when hypanthium present then semi-inferior), (bilocular or) trilocular to

quinquelocular (novem- to duodecemlocular in Beiselia); most locules

usually reduced and sterile. Style usually single, simple (stylodia sometimes

free at apex), usually short. Stigma capitate or (bilobate or) trilobate to

quinquelobate (novem- to duodecemlobate in Beiselia), with stigmatic

head formed by postgenital fusion, non-papillate?, type? Male flowers often

with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation

apical-axile. Ovules (one or) two per carpel, usually anatropous or

hemianatropous to campylotropous (rarely orthotropous), collateral, pendulous,

epitropous (in Beiselia superposed), usually bitegmic (rarely

unitegmic), crassinucellar. Micropyle usually endostomal (sometimes bistomal,

Z-shaped, zig-zag). Outer integument approx. four cell layers thick. Inner

integument approx. four cell layers thick. Obturator absent. Megasporangium six

to twelve cell layers thick. Nucellar cap massive. Megagametophyte monosporous,

Polygonum type. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm

haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit Usually a drupe with one

to five single-seeded pyrenes, or one multilocular pyrene (often with only one

locule developed); pyrene with valves (rarely winged); pseudo-aril sometimes

present (formed from pericarp in, e.g., Bursera and

Commiphora); mesocarp often dehiscing along loculicidal radius (rarely

a septifragal pseudocapsule with a columella; in Beiselia,

Boswellia and Triomma a dry schizocarp). Endocarp often

consisting of unorientated sclerified cells and crystalliferous cells.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat

testal. Exotesta sometimes with unthickened radially elongate cells. Endotesta

lignified, tracheidal. Tegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm very sparse

or absent. Embryo small, usually straight (rarely curved), well differentiated,

with hemicellulose, oil and proteins, with chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, usually

entire (sometimes palmately lobed, sometimes folded, rarely transversely folded

twice). Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = 11–13,

22–24

DNA Mitochondrial

coxI intron present in Bursera.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin), biflavones, bitter-tasting triterpenoid substances

(triterpenes with ursane and oleanane components), oleoresins (with mono- and

bicyclic monoterpenes), ellagic acid, alkaloids, ethereal oils, cyanidin

pentacyclic terpene saponins, and polyacetylenes present.

Use Aromatic substances (myrrh

and frankincense from Commiphora, Boswellia etc.), medicinal

plants, timber, carpentry, varnish (Bursera).

Systematics Burseraceae are sister-group to

Anacardiaceae.

Beiselia is sister to the remaining

Burseraceae (Clarkson

2002; Thulin & al. 2008).

Beiselieae Thulin,

Beier et Razafim. in Nord. J. Bot. 26: 226. 22 Dec 2008

1/1. Beiselia (1; B.

mexicana; Michoacán in Mexico). – Vessel elements sometimes with

scalariform perforation plates. Leaf bases? persistent and provided with spine.

Pistil composed of nine to twelve connate carpels. Ovary deeply furrowed.

Ovules superposed. Fruit a capsule with pericarp dehiscing septifragally

separately from endocarp; mericarps winged at apex; columella provided with

deep flanges. Cotyledons simple. n = ?

Burseroideae Arn.,

Botany: 106. 9 Mar 1832 [‘Burseraceae’]

18/>765.

Protieae Marchand in Adansonia 8: 62. Oct 1867.

Crepidospermum (6; C. atlanticum, C. cuneifolium,

C. goudotianum, C. multijugum, C. prancei, C.

rhoifolium; northern South America), Tetragastris (9; Central

America, the West Indies, tropical South America), ’Protium’

(>180; Madagascar, Mauritius, tropical Asia from Pakistan to New Guinea,

tropical America; polyphyletic). – Bursereae DC.,

Prodr. 2: 75. Nov (med.) 1825 [’Burseraceae’].

Aucoumea (1; A. klaineana; Central Africa); Bursera

(c 100; southwestern United States, Mexico, Central America, the West Indies,

northern South America), Commiphora

(c 190; tropical and subtropical Africa, Madagascar, the Arabian Peninsula to

India and Sri Lanka, Vietnam, tropical South America). –

Garugeae Marchand in Adansonia 8: 66. Nov 1867.

Garuga (4; G. floribunda, G. forrestii, G.

pierrei, G. pinnata; the Himalayas, Southeast Asia, Malesia to

Melanesia and tropical Australia), ’Boswellia’ (c 20; semiarid

regions in tropical Africa, Madagascar, Socotra, drier parts of tropical and

subtropical Asia; polyphyletic). – Canarieae Engl.

in H. G. A. Engler et C. G. O. Drude, Veg. Erde 9(3, 1): 780. 22-29 Jul

1915.Triomma (1; T. malaccensis; Bihar in India, West

Malesia), Ambilobea (1; A. madagascariensis; northernmost

Madagascar), Canarium (c 120; tropical Africa, Madagascar, islands in

the Indian Ocean, tropical Asia to southern China and New Guinea, northern and

eastern Australia, Fiji, Micronesia, Tonga, Samoa), Dacryodes (c 77;

tropical regions on both hemispheres), Santiria (22–24; West Africa,

Malesia), Trattinnickia (13–14; Costa Rica to Brazil and Bolivia),

Rosselia (1; R. bracteata; Rossel Island in the Louisiade

Archipelago southeast of New Guinea). – Unplaced

Burseroideae Haplolobus (c 16; Borneo, Sulawesi, the

Moluccas, New Guinea to Fiji and Samoa, with their highest diversity on New

Guinea), Pseudodacryodes (1; P. leonardiana; Congo),

Scutinanthe (2; S. brunnea, S. engleri; Sri Lanka,

West Malesia to Sulawesi). – Pantropical, with their highest diversity in

tropical Asia and tropical America. Characters principally as for Burseraceae. – The phylogenetic

relationship among the four clades are not resolved.

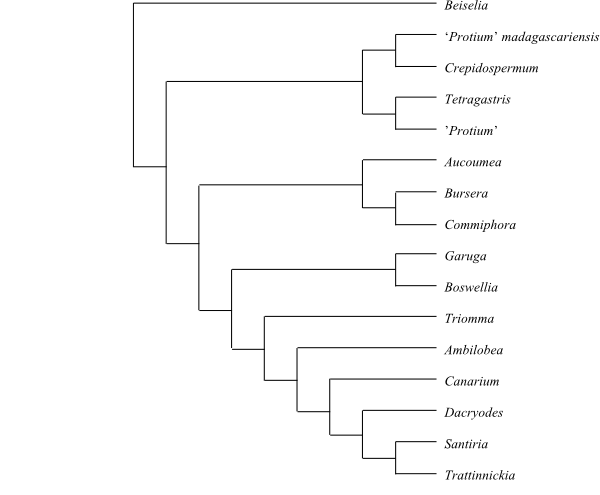

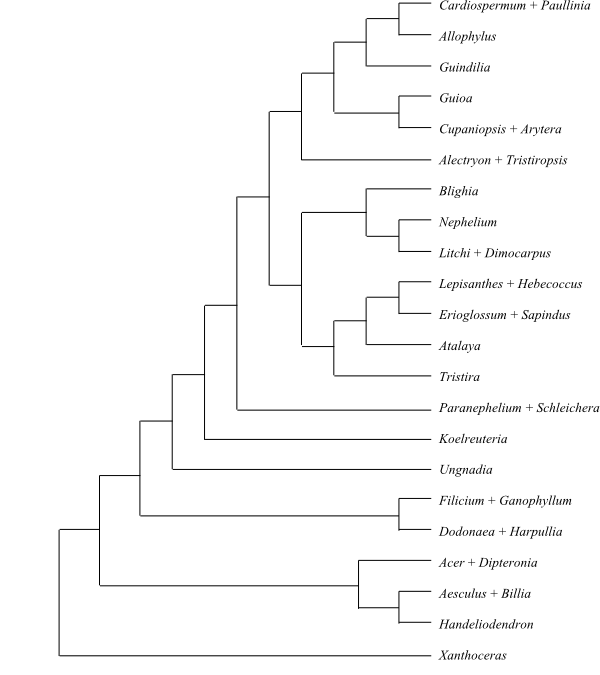

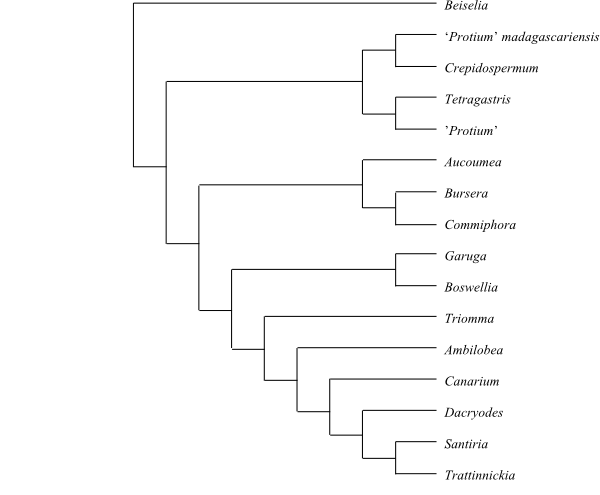

|

Bayesian majority rule consensus tree of

Burseraceae based

on DNA sequence data (Thulin & al. 2008).

|

Takhtajan, Sist. Filog. Cvetk. Rast. [Syst.

Phylog. Magnolioph.]: 321. 4 Feb 1967

Genera/species 1/6

Distribution Tropical and

subtropical East and Southeast Africa, Angola?, Madagascar.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Morphologically

bisexual, functionally monoecious, polygamomonoecious or dioecious, usually

deciduous trees or shrubs. Heartwood often honey-scented.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen?

Vessel elements with simple perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, simple

or bordered pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform fibres with

simple or bordered pits, septate. Wood rays multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial

parenchyma paratracheal vasicentric. Tyloses frequent. Sieve tube plastids S

type. Nodes usually 3:3?, trilacunar with three? leaf traces. Parenchyma

without secretory cavities. Crystals?

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or

multicellular, uniseriate or multiseriate; glandular hairs with multiseriate

stalk and multicellular head.

Leaves Alternate (spiral),

imparipinnate, leaflets entire, with ? ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent.

Petiole vascular bundle transection annular; petiole with medullary bundles.

Venation pinnate. Stomata anomocytic or paracytic? Cuticular waxes absent.

Epidermis sometimes with mucilaginous idioblasts. Leaflet margins serrate.

Inflorescence Axillary,

compound thyrsoid consisting of dichasial and monochasial cymes, changing

between functionally female and functionally male flowers from one branching

order to next.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small.

Hypogyny. Sepals (three or) four (to six), decussate, usually with valvate

(sometimes imbricate quincuncial) and later open aestivation, free or connate

at base. Petals (three or) four (to six), with open aestivation at base and

imbricate aestivation in upper part, free. Nectariferous disc intrastaminal,

annular, angular, wide, fleshy, well developed in male flowers, reduced in

female flowers.

Androecium Stamens (three or)

four (to six), haplostemonous, antesepalous, alternipetalous. Filaments

conical, free from each other and from tepals. Anthers dorsobasifixed,

non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by

longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory. Female flowers with staminodia.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains trisyncolporate, shed as monads,

bicellular at dispersal. Exine semitectate, with columellate infratectum,

reticulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

four (or eight) antepetalous connate carpels. Ovary superior, quadrilocular (or

octalocular), lobate. Gynophore short, glandular. Stylodia four (or eight),

separate, tightly connivent in lower part, connate in upper part, upright,

finally radiating. Stigmas four, short, connate, capitate, oblique, flattened,

papillate, Wet type. Male flowers with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation apical to

axile. Ovules one (or two) per carpel, epitropous (longitudinal direction of

ovule opposite involution direction of carpel) and somewhat campylotropous,

pendulous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle bistomal, Z-shaped (zig-zag),

elongate (outer integument longer than inner integument). Outer integument two

or three cell layers thick. Inner integument three or four cell layers thick.

Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development ab

initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A lignified schizocarp

with four (or seven or eight) nutlike mericarps, with ridges and persistent

columellar strands. Endocarp leathery, strongly lignified, with crystalliferous

cells and cells containing elongate sclereids. Mericarps single-seeded, pendant

from apex of central columella (carpophore) and dorsally with basal remnants of

stylodium recurved over apex.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa thin.

Exotesta? Endotesta? Tegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm sparse or

absent. Embryo somewhat curved, well differentiated. chlorophyll? Cotyledons

two. Germination?

Cytology n = ?

DNA

Phytochemistry Ellagic acid,

lignans and nor-carotenoids ((+)-dihydrodehydrodiconiferyl alcohol;

(+)-lyoniresinol; (-)-ent-isolariciresinol;

(-)-4′,9,9′-trihydroxy-3′-methoxy-3.O.8′,4.O.7′-neolignan;

(+)-de-O-methyllasiodiplodin; (+)-(6S,7E,9R)-blumenol A;

(+)-(6S,7E)-dehydrovomifoliol;

(+)-4-ethanone-3,4-dihydro-6,8-dihydroxy-5-methylisocoumarin;

(+)-(2R,3R)-7-O-methylaromadendrin; etc.) present. Quassinoids and limonoids

not found.

Use Timber, carpentry,

medicinal plants.

Systematics Kirkia (6; K.

acuminata, K. burgeri, K. dewinteri, K.

leandrii, K. tenuifolia, K. wilmsii; tropical and

subtropical East and Southeast Africa from Ethiopia to Transvaal, Angola?,

Madagascar).

Kirkia is sister to [Anacardiaceae+Burseraceae].

de Jussieu, Gen. Plant.: 263. 4 Aug 1789

[’Meliae’], nom. cons.

Cedrelaceae R. Br. in

M. Flinders, Voy. Terra Austr. 2: 595, 596. 19 Jul 1814

[’Cedreleae’]; Meliales Juss. ex Bercht.

et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 219. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Meliaceae’];

Swieteniales Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin:

219. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Swieteniae’];

Swieteniaceae E. D. M. Kirchn., Schul-Bot.: 415.

13-20 Oct 1831; Cedrelales R. Br. in C. F. P. von

Martius, Consp. Regn. Veg.: 61. Sep-Oct 1835 [‘Cedreleae’];

Aitoniaceae R. A. Dyer, Gen. S. Afr. Fl. Pl. 1: 298.

1975, nom. illeg.

Genera/species 48/650–665

Distribution Tropical and

subtropical lowland areas, mainly southern and southeastern Asia; few species

in warm-temperate regions; Xylocarpus consists of mangrove trees.

Fossils Eocene and Oligocene

fruits of Meliaceae are

found in North America and Eocene fruits in England.

Habit Bisexual, monoecious,

polygamomonoecious or dioecious, evergreen trees and shrubs (in

Munronia suffrutices, in Naregamia perennial herbs). Bark

often with a bitter taste, often with a strong garlic-like or sweet smell,

etc.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen

ab initio superficial. Vessel elements with simple perforation plates; lateral

pits alternate, bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre

tracheids or libriform fibres with simple or bordered pits, septate or

non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or

heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse, or paratracheal scanty,

aliform, lozenge-aliform, winged-aliform, confluent, vasicentric, or banded.

Wood elements often storied. Secondary phloem sometimes stratified into hard

fibrous and soft parenchymatous layers. Sieve tube plastids S type (in, e.g.,

Azadirachta and Melia Ps type with protein crystalloids and

starch). Nodes usually 5:5, pentalacunar with five leaf traces (sometimes 3:3,

trilacunar with three traces). Secretory cells with resins and ethereal oils

present in leaves, cortex and medulla (rarely with secretory cavities).

Laticifers with white latex present in heartwood of some species. Prismatic

calciumoxalate crystals frequent.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or

multicellular, simple, furcate or stellate, sometimes lepidote;

peltate-lepidote glandular hairs sometimes present.

Leaves Usually alternate

(spiral; in Turraea distichous; in Capuronianthus opposite),

usually paripinnate or imparipinnate (rarely trifoliolate or bipinnate; in

Nymania, Turraea and Vavaea simple [unifoliolate?]),

leaflets entire or lobed, with conduplicate? ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath

absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection annular? Leaf base swollen,

vertically elongate. Petiolules usually not articulated (in Walsura

often pulvinate). Venation pinnate. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax

crystalloids? Domatia as pits, pockets or hair tufts. Epidermis with or without

mucilaginous idioblasts. Mesophyll with or without sclerenchymatous idioblasts.

Secretory cells with resins and ethereal oils. Leaflet margins (or margin)

usually entire (sometimes serrate). Extrafloral nectaries sometimes present on

petiole and abaxial side of lamina.

Inflorescence Usually axillary

(sometimes terminal), raceme, spike or panicle with thyrsoid partial

inflorescences (flowers sometimes solitary or pairwise, axillary; rarely

epiphylly).

Flowers Usually actinomorphic

(rarely slightly zygomorphic). Hypogyny. Sepals (two to) three to five (to

eight), usually with imbricate (rarely valvate or open) aestivation, usually

entirely or partially connate. Petals three to seven (to 14), usually with

imbricate or contorted (rarely valvate) aestivation, usually in one whorl

(rarely two whorls), usually free (sometimes connate below). Nectariferous disc

intrastaminal, annular, or absent.

Androecium Stamens usually

four to ten (sometimes three or up to 20 or more, rarely up to c. 30), twice as

many as petals, diplostemonous, or three to six, haplostemonous. Filaments

usually connate into tube around pistil (staminal tube sometimes very long

[rarely up to 14 cm!], sometimes corolla-like), often also adnate to petals

(filaments in Vavaea, Walsura, Cedrela and

Toona secondarily free or almost free). Anthers dorsifixed, versatile,

tetrasporangiate, introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits).

Tapetum secretory, with binucleate to quadrinucleate (rarely up to

decemnucleate) cells. Staminodia few to numerous or absent; female flowers

often with staminodia. Secondary pollen display present in, e.g.,

Vavaea.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains (2–)3–5(–6)-colporate

(rarely porate), usually shed as monads (rarely tetrads), usually bicellular

(rarely tricellular) at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum,

rugulate, scabrate or psilate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

usually two to six (rarely one or in Turraea up to 20) antepetalous

connate carpels, postgenitally fused. Ovary superior, usually bilocular to

sexalocular (rarely unilocular or up to 20-locular). Style single, simple, or

absent. Stigma usually capitate, clavate or peltate (sometimes punctate or

lobate), usually large, papillate, Wet type. Male flowers often with

pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation usually

axile and ovary multilocular (rarely parietal and ovary unilocular). Ovules

usually two (sometimes one or more than two to numerous) per carpel,

anatropous, campylotropous or orthotropous (rarely amphitropous), usually

pendulous, epitropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle usually endostomal

(rarely bistomal or exostomal). Outer integument two to five cell layers thick.

Inner integument two to four cell layers thick. Placental obturator often

present. Parietal tissue three to nine (to 18) cell layers thick. Archespore

often multicellular. Nucellar cap present. Megagametophyte monosporous,

Polygonum type. Synergids sometimes with a filiform apparatus.

Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis

onagrad.

Fruit A loculicidal or

septicidal capsule, a berry or drupe (rarely a nutlet).

Seeds Seeds often

pachychalazal, often with chalazal aril and/or sarcotesta (Melioideae)

or with suberinized/corky outer layer, or seeds winged and inserted at woody

central columella (Cedreloideae). Seed coat usually exotegmic

(sometimes reduced and undifferentiated). Testa vascularized, usually

multiplicative. Exotesta unspecialized. Endotesta with calciumoxalate crystals.

Tegmen usually multiplicative. Exotegmen usually fibrous. Endotegmen

unspecialized? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm usually absent (rarely

copious). Embryo straight or curved, elongate, well differentiated, with or

without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar or

cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = 10–14

(sometimes more); x = 6 or 7

DNA Mitochondrial

coxI intron present.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin), flavones, cyanidin, tetracyclic triterpenes,

tetranortriperpenes, pentanortriterpenes, limonoids and meliacins and other

bitter-tasting triterpenoid substances (turraeanthin, melianone, azadirone,

homoazadirone, azadiradione, gedunin, grandifolin, khivorin, khivol,

anthothecol, andirobin, methyl angolensate, nimbin, salannin, mexicanolide,

swietenine, astrotrichilin, etc.), tannins, proanthocyanidins, alkaloids,

triterpene saponins, polyacetylenes, coumarins, and ethereal oils present.

Ellagic acid and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Ornamental plants, fruits

(Lansium domesticum, Sandoricum koetjape), seed oils,

medicinal plants, cosmetics, timber (e.g. Swietenia, Khaya),

carpentries.

Systematics (under

construction) Meliaceae are

sister to Simaroubaceae.

The subdivision below follows Muellner &

al. 2003, and Muellner, Samuel & al. 2008. Two main clades can be

discerned, corresponding to Melioideae and Cedreloideae,

respectively.

Melioideae Arn.,

Botany: 103. 9 Mar 1832 [‘Melieae’]

34/580–585. Azadirachta (2;

A. excelsa, A. indica; tropical Asia), Melia (2;

M. volkensii: southern tropical Africa; M. azedarach:

tropical Asia to New Guinea), Astrotrichilia (c 12; Madagascar);

Quivisianthe (1–2; Q. papinae; Madagascar),

Walsura (16; India and Sri Lanka to New Guinea); Sandoricum

(4; S. bamboli, S. beccarianum, S. dubia, S.

koetjape; Malesia; three species endemic to Borneo); Munronia (3;

M. humilis, M. pinnata, M. unifoliolata; subtropical

China and tropical Asia to Timor), Lepidotrichilia (4; L.

ambrensis, L. convallariiodora, L. sambiranensis, L.

volkensii; tropical East Africa, Madagascar), Vavaea (4?; V.

amicorum, V. australiana, V. bantamensis, V.

pauciflora; Sumatra and the Philippines to northern Australia, Fiji, the

Caroline Islands and Tonga), Pseudoclausena (1; P.

chrysogyne; Indochina to New Guinea), Cipadessa (1; C.

baccifera; tropical and subtropical Asia from India, Sri Lanka and Nepal

to southern China, Indochina and Central Malesia), Ekebergia (4;

E. benguelensis, E. capensis, E. pterophylla, E.

pumila; tropical and southern Africa), Trichilia (c 95; tropical

Africa, Madagascar, tropical America), Owenia (5; O. acidula,

O. cepiodora, O. reliqua, O. reticulata, O.

vernicosa; northern, central and eastern Australia), Malleastrum

(23; Madagascar, the Comoros, Aldabra), Pterorhachis (2; P.

letestui, P. zenkeri; Central Africa), Nymania

(1; N. capensis; southern Namibia, Northern, Western and Eastern

Cape), Calodecaryia (2; C. crassifolia, C.

pauciflora; Madagascar), Humbertioturraea (10; Madagascar), Turraea (c

60; tropical and southern Africa, Madagascar, the Mascarene Islands, Socotra,

tropical Asia to northern and eastern Australia), Synoum (1; S.

glandulosum; eastern Queensland, eastern New South Wales),

Anthocarapa (1; A. nitidula; northeastern and southeastern

Queensland, northeastern New South Wales, New Guinea to New Caledonia and

Rotuma), Heckeldora (7; H. acuminata, H.

angustifolia, H. klainei, H. latifolia, H.

mangenotiana, H. staudtii, H. zenkeri; tropical West and

Central Africa), Turraeanthus (3; T. africana, T.

longipes, T. mannii; western and central tropical Africa),

Guarea (c 40; tropical Africa, Central America, tropical South

America), Ruagea (12; Guatemala to Peru), ’Dysoxylum’ (c

80; India and Sri Lanka to southern China, Indochina, Malesia to New Guinea,

Christmas Island, islands in southern and southwestern Pacific to northern and

eastern Australia, New Caledonia, Norfolk Island, Lord Howe, New Zealand, Tonga

to Niue; non-monophyletic?), Chisocheton (53–55; Assam, southern

China, Southeast Asia, Malesia to northeastern Queensland and Vanuatu),

Cabralea (1; C. canjerana; Central America, tropical South

America), Sphaerosacme (1; S. decandra; the Himalayas),

'Aglaia' (c 120; tropical Asia to islands in western Pacific;

paraphyletic; incl. Aphanamixis?), Aphanamixis (3; A.

borneensis, A. polystachya, A. sumatrana; tropical Asia

to Solomon Islands; in Aglaia?), Lansium (1; L.

parasiticum; Malesia; in Aglaia?), Reinwardtiodendron

(7; R. anamalaiense, R. celebicum, R. cinereum,

R. humile, R. kinabaluense, R. kostermansii, R.

merrillii; Southeast Asia, West and Central Malesia; in Aglaia?).

– Pantropical, with their largest diversity in tropical regions in the Old

World. Trees or shrubs. Buds naked. Stigma capitate. Ovules usually one to

three (rarely numerous) per carpel, epitropous. Fruit usually a loculicidal

capsule (rarely berry, drupe or nut). Seeds usually without wings (in

Quivisianthe winged), usually with arillode (in Naregamia

funicular aril) or sarcotesta. n = 8, 11, 12, 14, 15, 18 up to 140. –

Guarea in tropical America and Chisocheton in Malesia have

leaves with unlimited growth. The clade [Melia+Azadirachta]

is sister-group to the remaining Melioideae and has several unique

anatomical features, such as clusters of minute vessels with spiral wall

thickening (Muellner, Samuel & al. 2008). The position of

Ekebergia is doubtful. In the rbcL tree in Muellner, Samuel

& al. (2008), it is recovered as sister to Quivisianthe,

Sandoricum being sister to the other two genera. In the Bayesian ITS

nrDNA tree, Ekebergia is nested inside the

Turraeeae/Trichilieae clade and sister to Cipadessa,

whereas Quivisianthe and Walsura form a subbasal clade in

Melioideae.

Cedreloideae Arn.,

Botany: 103. 9 Mar 1832 [‘Cedreleae’]

14/70–80. Chukrasia (1;

C. tabularis; India, Sri Lanka and southern China to West Malesia),

Schmardaea (1; S. microphylla; the Andes from Venezuela to

Peru), Neobeguea (3; N. ankaranensis, N. leandriana,

N. mahafaliensis; Madagascar), Cedrela (c 17; southern

Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America),

Toona (5; T. australis, T. ciliata, T.

fargesii, T. sinensis, T. sureni; eastern Pakistan to

southern China, Southeast Asia to eastern Queensland and eastern New South

Wales), Capuronianthus (2; C. mahafalensis, C.

vohemarensis; Madagascar; in Lovoa?), Lovoa (3; L.

swynnertonii, L. tomentosa, L. trichilioides; tropical

Africa; incl. Capuronianthus?), Carapa (10–20; tropical

Africa, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America),

Xylocarpus (3; X. granatum, X. moluccensis, X.

rumphii; mangroves in East Africa to Tonga), Khaya (6; K.

anthotheca, K. grandifoliola, K. ivorensis, K.

madagascariensis, K. nyasica, K. senegalensis; tropical

Africa, Madagascar), Swietenia (5; S. aubrevilleana, S.

humilis, S. krukovii, S. macrophylla, S.

mahagoni; Florida, Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical

South America), Entandrophragma (11; tropical Africa),

Pseudocedrela (1; P. kotschyi; tropical Africa),

Soymida (1; S. febrifuga; India, Sri Lanka). – Pantropical,

with their highest diversity in tropical regions in tropical Africa and

Madagascar. Buds usually perulate (in Capuronianthus naked). Stylar

apex usually discoid (rarely capitate). Ovules usually three to numerous (in

Capuronianthus two) per carpel, collateral. Fruit a septifragal

capsule with caducous valves, persisting central columella and winged seeds, or

rudimentary columella and seeds with massive woody or corky testa. n = 13, 18,

23, 25, 26, 28.

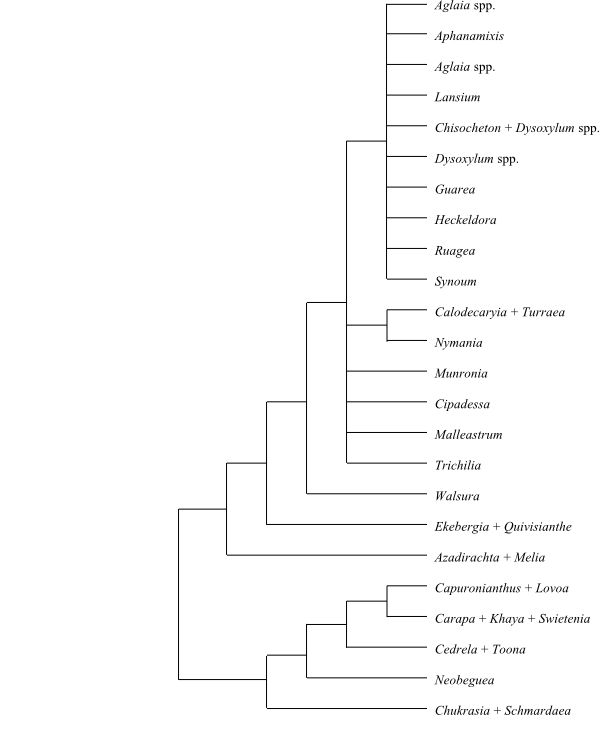

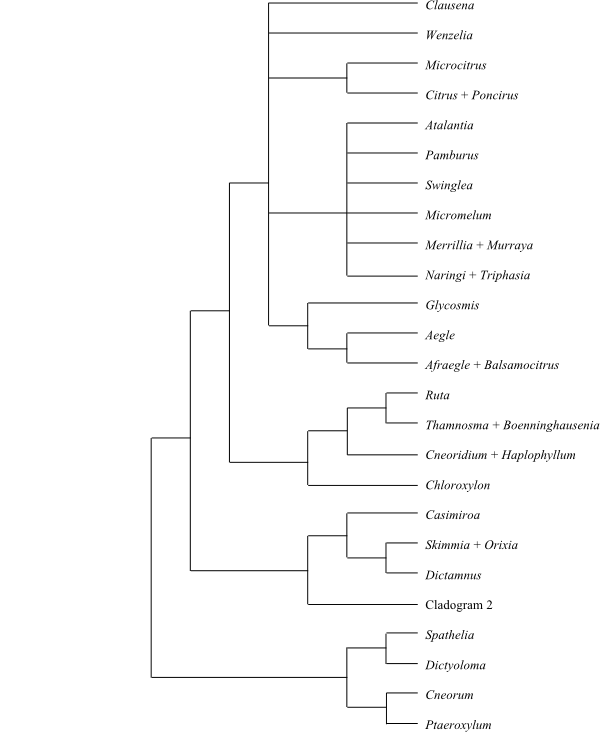

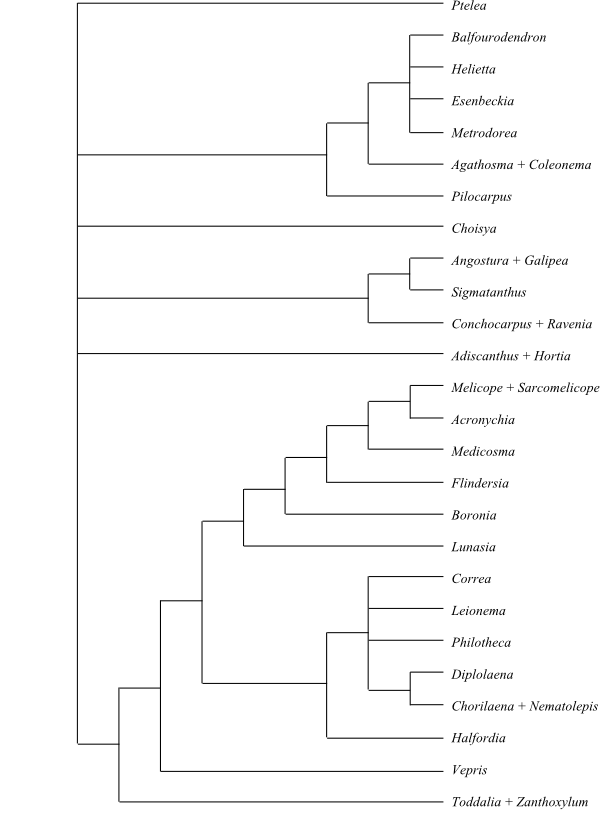

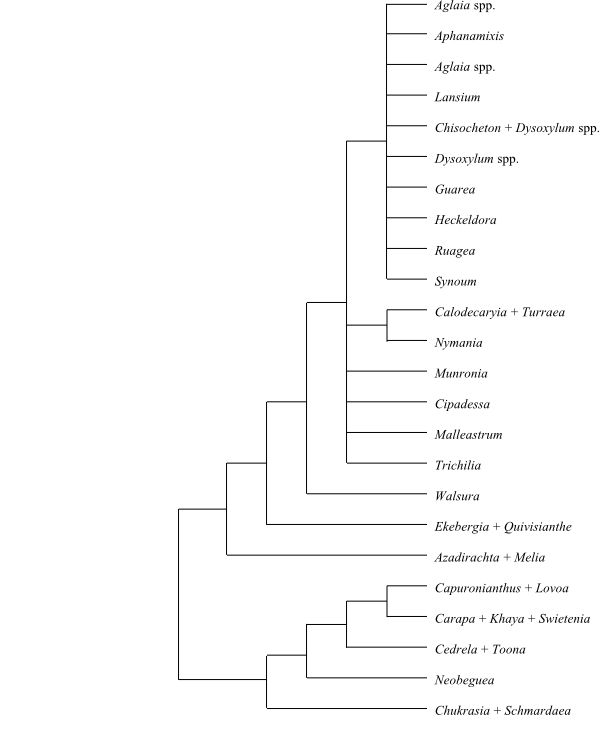

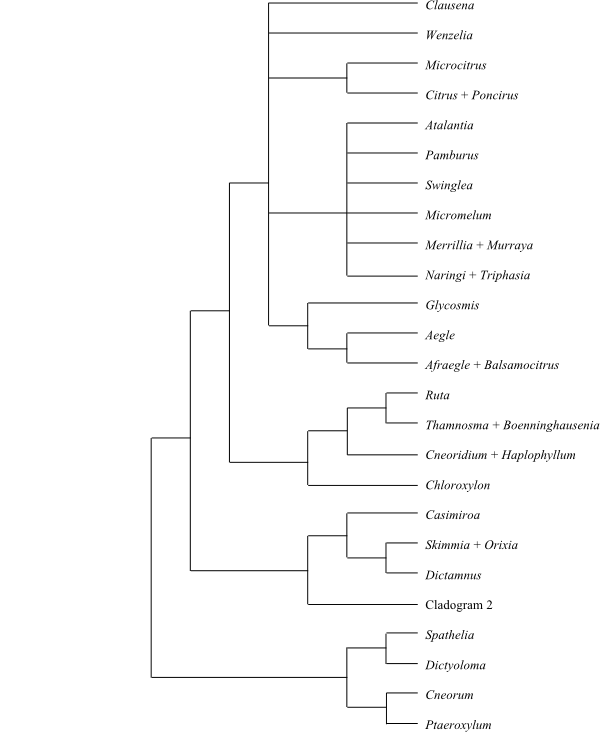

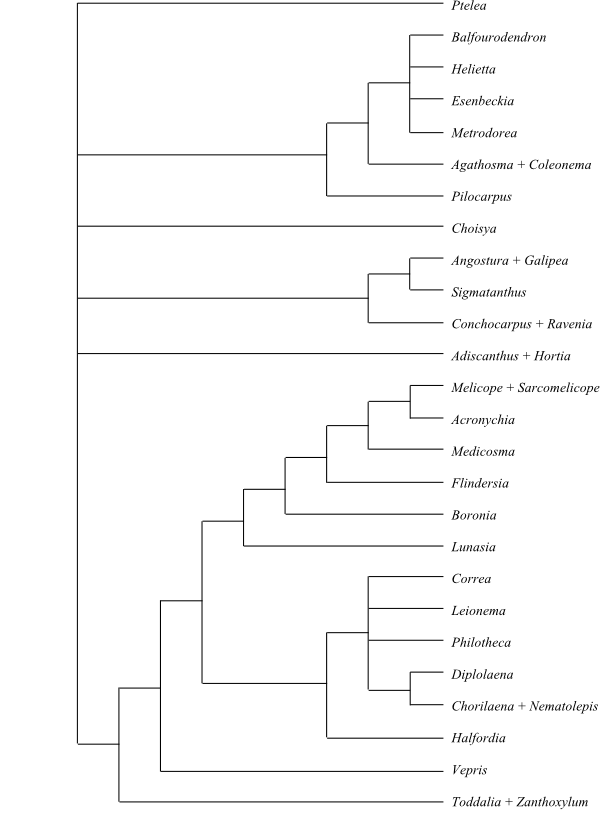

|

Cladogram of Meliaceae based on DNA

sequence data (Muellner & al. 2003).

|

Lindley, Intr. Nat. Syst. Bot.: 149. 27 Sep

1830

Nitrariales Bercht.

et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 238. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Nitrariae’];

Tetradiclidaceae (Engl.) Takht., Florist. Reg. World:

333. 27 Apr 1986; Peganaceae (Engl.) Tiegh. ex

Takht., Sist. Magnoliof. [Systema Magnoliophytorum]: 178. 24 Jun 1987

Genera/species 4/16–17

Distribution North Africa,

southern and southeastern Europe to Siberia and Mandshuria, Afghanistan,

Central Asia, the Arabian Peninsula, southern Australia, southeastern Texas,

northern Mexico.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, deciduous

shrubs (Malacocarpus, Nitraria) or perennial

(Peganum) or annual (Tetradiclis) herbs. Often xerophytic.

Often succulent. Sometimes spiny.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza

absent in at least Peganum. Phellogen ab initio inner-cortical.

Primary vascular tissue cylinder, without separate vascular bundles. Vessel

elements with simple perforation plates; lateral pits usually alternate,

bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform fibres usually

with bordered (sometimes simple) pits, non-septate (in Nitraria also

vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or

heterocellular. Axial parenchyma usually apotracheal (at least in

Nitraria paratracheal aliform-confluent, vasicentric, or banded). Wood

elements and/or parenchyma storied. Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes 3:3,

trilacunar with three leaf traces. Secretory cavities and mucilage cells

present in Nitraria. Heartwood in Nitraria with gum-like

substances. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals frequent.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or

multicellular, uniseriate and complex capitate hairs (not in

Nitraria); uniseriate glandular hairs present in Peganum.

Leaves Usually alternate

(spiral; in Nitraria often two or three per node; in Peganum

often two per node; two lowermost leaf pairs in leaf rosette of

Tetradiclis opposite), simple or pinnately or palmately compound,

entire or pinnately or palmately lobed, often carnose, sometimes coriaceous,

with ? ptyxis. Stipules small, bristle-like or foliaceous (in Peganum

often also divided), cauline or intrapetiolar, persistent or caducous (absent

in Tetradiclis); leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle

transection arcuate; petiole with wing bundles. Venation pinnate or palmate

(leaves sometimes one-veined). Stomata usually anomocytic (sometimes paracytic

or actinocytic). Cuticular waxes usually absent (wax crystalloids rarely as

platelets or rodlets). Epidermis with or without mucilaginous idioblasts.

Mesophyll in Nitraria sometimes with mucilaginous idioblasts and

occasionally with sclerenchymatous idioblasts. Calciumoxalate as raphides

(Peganum, Malacocarpus), druses and solitary prismatic

crystals. Leaflet margins usually entire (rarely serrate or lobate).

Inflorescence Terminal or

axillary, cymose (in Nitraria scorpioid), or flowers solitary

axillary. Floral prophyls (bracteoles) absent in Nitraria.

Flowers Actinomorphic.

Hypanthium present. Hypogyny. Sepals (three or) four or five (in

Tetradiclis usually four), with usually imbricate (in Peganum

valvate) aestivation, sometimes pinnately compound, often persistent, free or

more or less connate (Nitraria, Tetradiclis). Petals (three

or) four or five (in Tetradiclis usually four), with imbricate,

contorted or (induplicate-)valvate aestivation, free. Nectariferous disc

extrastaminal or intrastaminal, annular (in Nitraria and

Peganum as antepetalous nectaries; nectary in Tetradiclis

absent).

Androecium Stamens 5+5, 4+4+4,

or 15 in antesepalous fascicles of three, or in antepetalous pairs

(occasionally five; in Peganum sometimes paired, antepetalous; in

Tetradiclis usually four, antesepalous), obdiplostemonous (sometimes

haplostemonous). Filaments free from each other and from tepals, in

Nitraria inserted at hypanthium, often widened at base. Anthers

dorsifixed, versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by

longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory, with binucleate cells (in

Peganum finally often polyploid; in Tetradiclis finally

modified into false plasmodium). Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grans 3(–4)-colporate, shed as monads,

bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate

infratectum, reticulate (sometimes reticulate-rugulate) or striate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

two to four (or six) connate carpels (carpels in Nitraria and

Tetradiclis alternisepalous, antepetalous; each of usually four

carpels in Tetradiclis divided into three partitions). Ovary superior,

bilocular to quadrilocular, in Tetradiclis on gynophore. Style single,

simple, usually terminal (in Nitraria and Tetradiclis basal),

sometimes hollow. Stigma usually two- to four-keeled (rarely six-keeled), as

commissural compital lines down upper part of style (stigma in

Tetradiclis clavate, tetrasulcate, with four short decurrent double

rows of papillae, stigmatic ridges running down widened apical part),

papillate, Dry type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation axile to

apical (in Nitraria subapical; ovules in Tetradiclis

pendulous from free basal-central placenta). Ovules one (Nitraria) or

six (Tetradiclis: four ovules in central locellus and one ovule in

each of two lateral locelli) or numerous (Peganum,

Malacocarpus) per carpel, usually anatropous (in Tetradiclis

hemianatropous), pendulous, apotropous or epitropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar.

Micropyle bistomal, Z-shaped (zig-zag). Outer integument two to four cell

layers thick, in Tetradiclis with mucilage cells. Inner integument two

or three, or four to seven cell layers thick. Funicular-placental obturator

present in Malacocarpus. Parietal tissue approx. three cell layers

thick. Endothelium absent. Archespore in Peganum multicellular.

Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development ab

initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis solanad

(Nitraria).

Fruit A loculicidal capsule

(Peganum, Tetradiclis), a single-seeded drupe with lignified

scleromesocarp (Nitraria), or a berry (Malacocarpus,

Peganum). In Tetradiclis only seeds of central locelli

liberated as capsule opens, seeds in lateral locelli liberated later.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa in

Peganum and Malacocarpus spongy, mucilaginous, in

Tetradiclis thin, in Peganum multiplicative. Exotesta and

endotesta (short) palisade; exotestal cells often enlarged (cells in

Tetradiclis inflated), sometimes mucilaginous; endotesta often

palisade. Exotegmen crushed. Endotegmic cells tangentially elongate; endotegmen

in Peganum almost fibriform, with lignified cells. Perisperm not

developed. Endosperm sparse to copious, oily, or absent. Embryo straight or

curved, well differentiated, sometimes with chlorophyll. Cotyledons two.

Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 7

(Tetradiclis), 12, 13 (Peganum, Malacocarpus,

Nitraria), 30 (Nitraria)

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin), flavonoids (apigenin, rutin, kaempferol,

isorhamnetin-3-rhamnogalactoside in Nitraria), β-carboline alkaloids (harmine,

harmaline, harmalol) and pyrroloquinazoline alkaloids (vasicine, vasicinone,

desoxyvasicinone, etc.) present. Nitrarin and carbolin present in Nitraria, in

Peganum also peganol and peganine; anabasin D in Malacocarpus. Mustard oils

reported from some species. Proanthocyanidins and cyanogenic compounds not

found. Ethereal oils?

Use Dyeing substances (turkish

red) from seeds used for dyeing hats (tarboosh), medicinal plants and narcotics

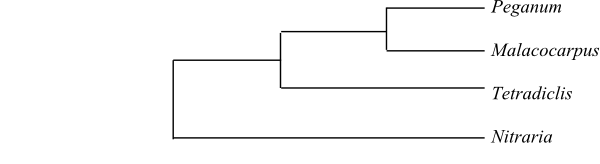

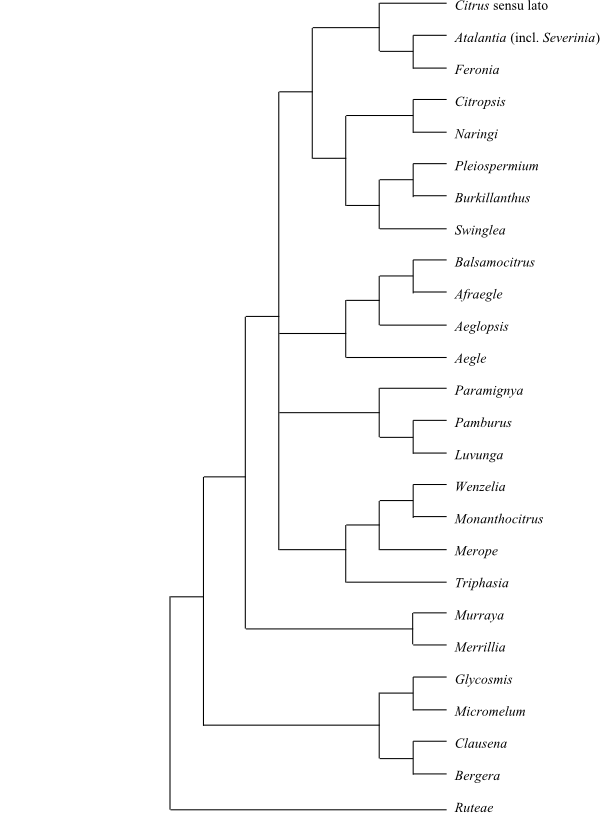

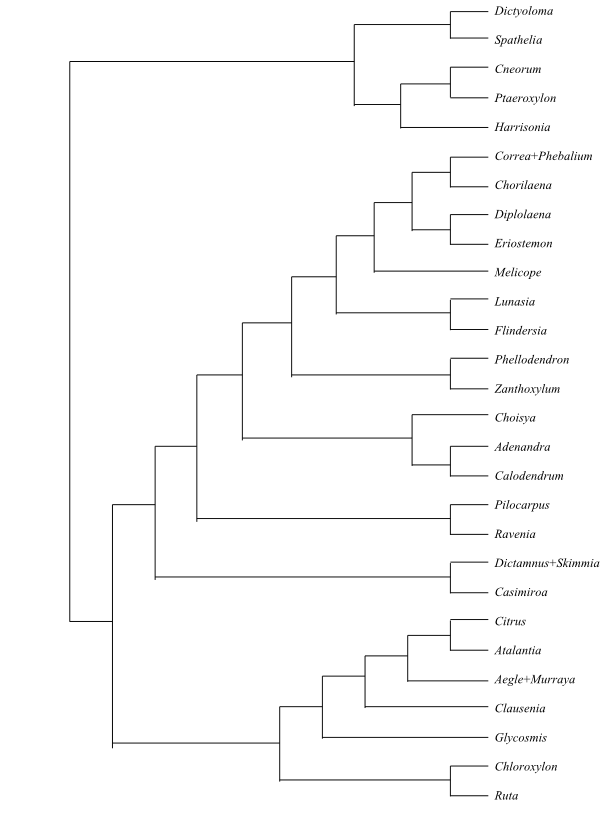

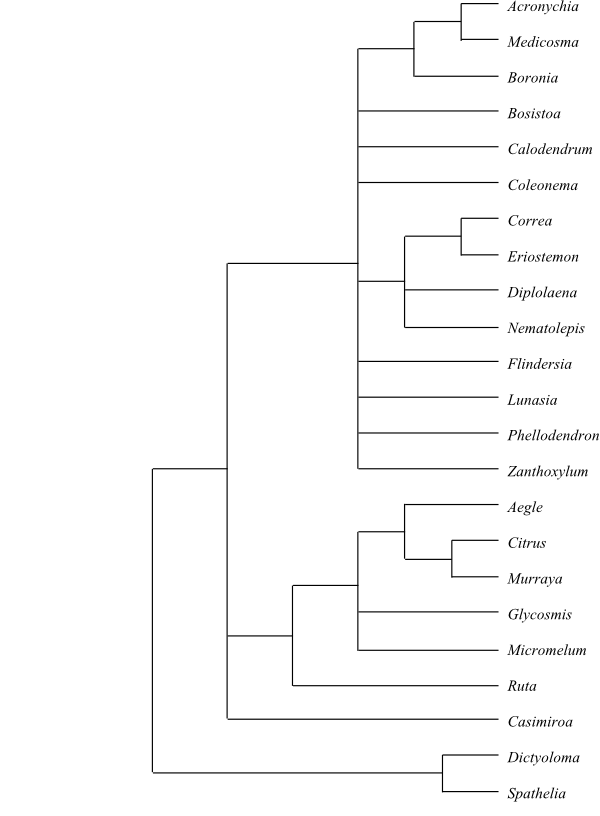

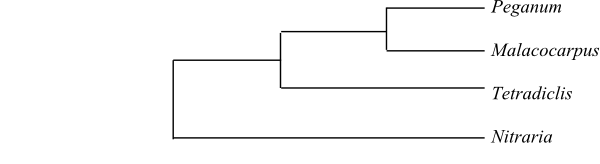

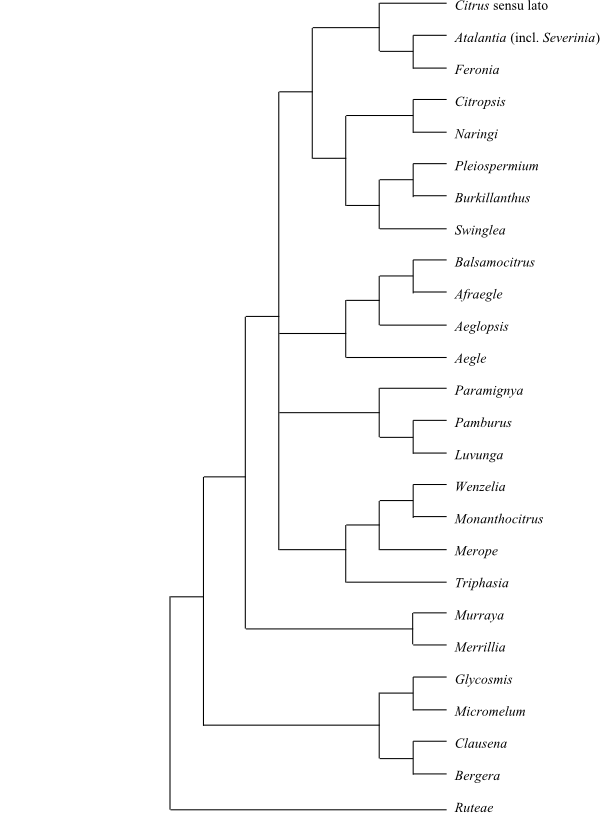

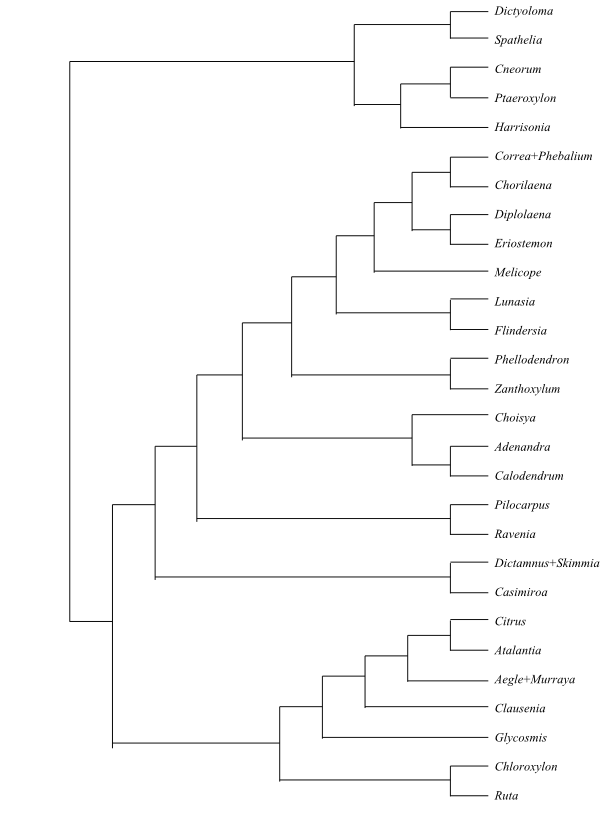

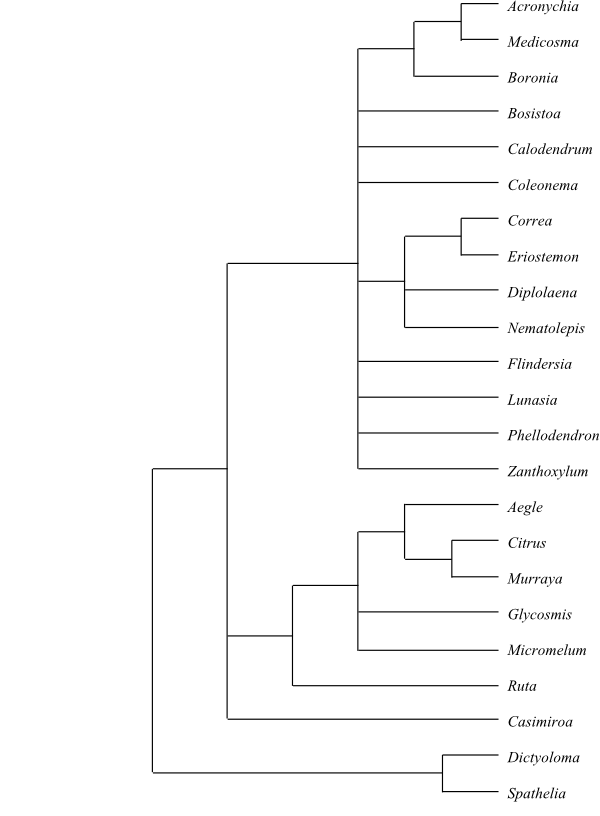

(Peganum harmala).