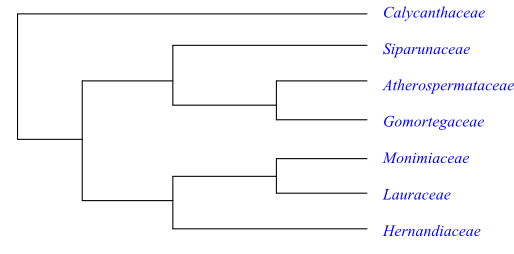

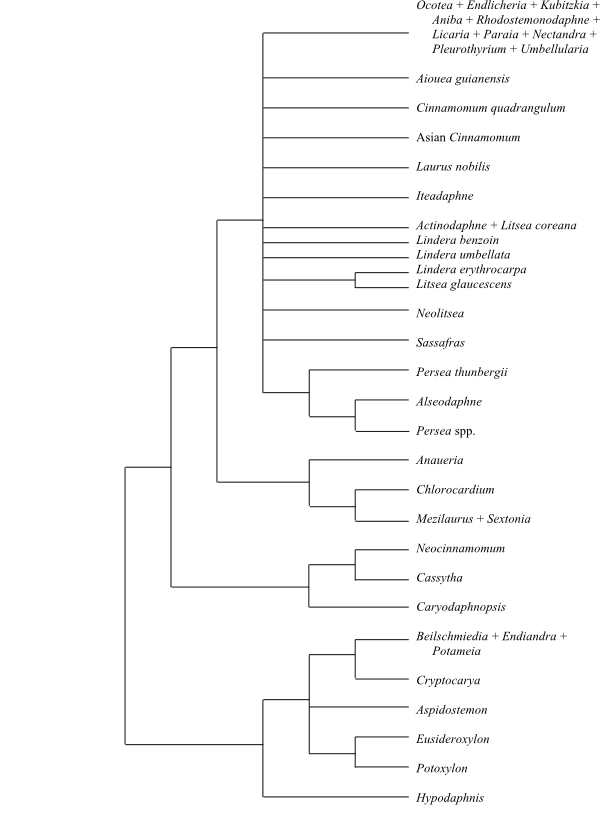

Cladogram of Laurales based on DNA sequence data (Renner 1999; Massoni & al. 2014). Lauraceae are sister to [Hernandiaceae+Monimiaceae], according to Soltis & al. (2011).

Lauropsida Horan., Prim. Lin. Syst. Nat.: 59. 2 Nov 1834 [’Laureales’]; Lauranae Takht., Divers. Classif. Fl. Pl.: 53. 24 Apr 1997; Lauridae C. Y. Wu in Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 40: 292. 2002

Fossils Fossilized hermaphroditic lauralean flowers, Saportanthus, with spirally arranged organs were described from Early Cretaceous layers in Portugal. Trimerous floral fossils from the Early to mid-Albian of Virginia have been assigned to Laurales. In one of the flowers the six anthers dehisced by apical valves and the gynoecium consists of a single carpel. The Late Albian to Early Cenomanian Australian (Queensland) floral fossil Lovellea wintonensis has 16 tepals and 16 stamens situated on the margin of a cup-shaped hypanthium. The c. 40 free uniovulate carpels are adnate to the hypanthium wall and the styles are free. The morphology corresponds well with Gomortega and some Monimiaceae.

Habit Bisexual, monoecious, andromonoecious, gynomonoecious, polygamomonoecious, dioecious, androdioecious or polygamodioecious, usually evergreen (sometimes deciduous) trees or shrubs (sometimes lianas). Bark and leaves usually aromatic.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza? Phellogen ab initio usually superficial (rarely pericyclic). Vessel elements with usually simple or scalariform (sometimes reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, scalariform or opposite, simple or bordered pits. Vestured pits sometimes present. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids, fibre tracheids or libriform fibres with simple or bordered pits, septate or non-septate (often also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma usually paratracheal scanty, aliform, lozenge-aliform, winged-aliform, confluent, vasicentric, unilateral, or banded (sometimes apotracheal diffuse), or often absent. Wood elements often storied. Sieve tube plastids usually Psc type (sometimes Pcsf or S type). Nodes 1:1–3, unilacunar with one to three leaf traces (sometimes five to seven traces). Pericycle often with hippocrepomorphic sclereids. Silica bodies present in some species. Calciumoxalate as prismatic or acicular crystals, styloids or crystal sand sometimes present.

Trichomes Hairs usually unicellular (sometimes multicellular), simple, furcate, T-shaped, stellate, peltate, lepidote, or absent.

Leaves Usually alternate (sometimes opposite, rarely verticillate), simple, usually entire (rarely lobed or scale-like), often coriaceous, with conduplicate, supervolute, involute, flat or curved ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection usually arcuate (sometimes flattened annular). Venation usually pinnate, brochidodromous (rarely palmate, triplinerved to eucamptodromous or pedate). Stomata usually paracytic (sometimes anomocytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids as platelets or rodlets (often transversely ridged Aristolochia type crystalloids), chemically characterized by presence of palmitone (hentriacontan-16-one) and absence of nonacosan-10-ol. Lamina usually gland-dotted. Domatia (as hair tufts or pockets, also acarodomatia) sometimes present in axils of abaxial secondary veins. Mesophyll usually with idioblasts (secretory cavities) containing ethereal oils and sometimes calciumoxalate crystals. Mucilage cells sometimes present. Secretory cavities with resins usually absent. Leaf margin usually entire (sometimes serrate with monimioid teeth).

Inflorescence Usually axillary (sometimes terminal), umbel-like, corymb, panicle, thyrse or cyme (rarely capitate, spicate or raceme; flowers rarely solitary axillary).

Flowers Usually actinomorphic (rarely zygomorphic). Receptacle expanded into cupular, campanulate or urceolate hypanthium, surrounding floral parts. Usually hypogyny (sometimes half epigyny or epigyny). Tepals usually 3+3(+3) (sometimes 3, 2+2[+2] or 4+4, rarely up to 40), with usually imbricate (sometimes valvate, rarely decussate) aestivation, spiral or whorled, sepaloid or petaloid, usually free, or absent. Nectariferous disc present or absent.

Androecium Stamens (one or) two to more than 150, spiral or whorled. Filaments free or connate at base, free from tepals, often with two basal nectariferous glands. Anthers basifixed (to subbasifixed), non-versatile, disporangiate or tetrasporangiate, introrse, extrorse or latrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits) or valvicidal (dehiscing from base by two or four longitudinal valves; sometimes poricidal). Tapetum usually amoeboid-periplasmodial, with binucleate or quadrinucleate cells (sometimes secretory). Staminodia intrastaminal, extrastaminal or absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous or successive. Pollen grains inaperturate, dicolpate (with diffuse apertures), disulcate, di- or trisulculate or meridionosulcate, usually shed as monads (rarely tetrads), usually bicellular (rarely tricellular) at dispersal. Exine extremely thin, tectate (sometimes almost intectate), with usually granular acolumellate infratectum (infratectum sometimes absent), usually imperforate or microperforate, echinate (sometimes verrucate, rugulate or spinulate), striate (sometimes tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, perforate or reticulate, psilate).

Gynoecium Carpels one to more than 100, free (apocarpy), spiral, often enclosed by receptacle; carpel plicate and ascidiate (intermediary), postgenitally occluded by fusion, with or without secretory canal. Ovary usually superior (sometimes semi-inferior or inferior), unilocular (to quinquelocular). Stylodium single, simple, or stylodia lateral to gynobasic, or absent. Stigma capitate, discoid, lobate or decurrent, papillate or non-papillate, Dry or Wet type. Male flowers often with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation apical, subapical, basal or marginal. Ovule one per ovary, or one per carpel, usually anatropous (rarely hemianatropous), ascending or pendulous, apotropous, usually bitegmic (sometimes unitegmic), crassinucellar. Micropyle usually endostomal (rarely bistomal; megasporangium sometimes not completely covered by integuments, micropyle then absent). Archespore usually unicellular (rarely multicellular). Nucellar cap or nucellar beak often present. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Synergids usually with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells persistent, sometimes proliferating, or antipodal nuclei early degenerating (antipodal cells sometimes two). Endosperm development ab initio nuclear or cellular. Endosperm haustoria micropylar or absent. Embryogenesis onagrad, asterad, piperad, or undefined.

Fruit A single-seeded berry, a drupe or an assemblage of achenes or drupelets surrounded by lignified or fleshy hypanthium (rarely a samara).

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat testal, exotestal or endotestal. Testa usually thin, multiplicative. Mesotesta usually unspecialized, crushed, or absent. Endotesta tracheidal, with lignified cell walls, or undeveloped. Tegmen unspecialized, crushed. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, oily, or absent (often ruminate). Embryo large to small, straight, well differentiated, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two (to four). Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = 10–12, 15, 19–22, 24, 30, 36, 39, 41, 43, 44, 48, 57 or more

DNA Gene PI duplicated. Intergenic inversion of c. 200 bp present in plastid inverted repeat (IR region).

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, isorhamnetin), 5-O-methylflavonols, flavones, luteolin, sesquiterpene lactones, proanthocyanidins, isoquinoline alkaloids (benzylisoquinoline alkaloids, liriodenine etc., roemerine and other aporphine alkaloids), protoberberine alkaloids, indole alkaloids (calycanthidine, calycanthine, tryptamine), cyanogenic glycosides (taxiphyllin), myristicin, asarone, lignans (austrobailignan, veraguensin etc.), neolignans, polyketides (acetogenins), nitrophenyl ethan, germacrane-like compounds, myo-inisitol, syringaresinol, galbacin, licarin A, arbutin, and phenanthrenes present. Ellagic acid, condensed tannins and sesquiterpenes not found.

Systematics Calycanthaceae are sister-group to the remaining Laurales. Potential synapomorphies in Laurales excluding Calycanthaceae are, according to Stevens (2001 onwards), are e.g.: pericycle often with hippocrepomorphic sclereids; leaf margin sometimes with fairly distant teeth, glandular cap entered by one opaque persistent vein; filaments provided with paired basal nectariferous glands; anthers disporangiate and unithecal, with valvate dehiscence; pollen grains inaperturate, with spinulate sexine; and uniovular carpels.

Siparunaceae, Gomortega (Gomortegaceae) and Atherospermataceae do not seem to share any obvious morphological synapomorphies and the phytochemistry is very insufficiently investigated. Gomortega and Atherospermataceae have the following potential synapomorphies in common: presence of bud scales; protein fibrils present in sieve tube plastids; and outer (not inner) stamens staminodial (if present).

Monimiaceae, Lauraceae and Hernandiaceae share the characters: usually whorled stamens; usually reduced exine and absence of endexine, columellae and foot layer; and placentation usually apical. Hernandiaceae and Lauraceae have the following presumed synapomorphies: absence of separate vascular bundles in the primary stem; usually simple vessel perforation plates (rare in Monimiaceae); mucilage cells sometimes present; leaves spiral, with entire margin; floral parts always whorled; tapetum amoeboid-periplasmodial; intine usually thick; pistil composed of a single carpel; outer integument usually more than five cell layers thick; ovules usually pachychalazal; megagametophyte linear and often elongate; hypostase usually absent; testa usually vascularized and multiplicative; tegmen ephemeral (early crushed); and absence of endosperm. However, Lauraceae are sister to either Monimiaceae or [Hernandiaceae+Monimiaceae] in most molecular analyses.

|

Cladogram of Laurales based on DNA sequence data (Renner 1999; Massoni & al. 2014). Lauraceae are sister to [Hernandiaceae+Monimiaceae], according to Soltis & al. (2011). |

ATHEROSPERMATACEAE R. Br. |

( Back to Laurales ) |

Atherospermatales R. Br. in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp. Regn. Veg.: 38. Sep-Oct 1835 [‘Atherospermeae’]

Genera/species 6–7/18

Distribution New Guinea, eastern and southeastern Australia, Tasmania, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Chile, southern Argentina.

Fossils The oldest fossil remnants of Atherospermataceae are pollen grains from the Coniacian (the Kerguelen Plateau) and wood represented by Laurelites jamesrossii from the Campanian of Antarctica and Late Cretaceous Protoatherospermoxylon (South Africa). Pollen, leaves and wood of Atherospermataceae are more frequent in Cenozoic layers of southern South America, Africa, Tasmania, New Zealand and Antarctica, and also from Eocene layers in Germany and Austria.

Habit Bisexual, monoecious, polygamomonoecious, or dioecious, evergreen trees (rarely shrubs). Aromatic.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio superficial. Primary stem? Vessel elements with scalariform or reticulate perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform or opposite, simple pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements ? with bordered pits, septate or non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma rare (apotracheal diffuse) or absent. Sieve tube plastids usually Pcsf type (PIa type; sometimes Psc type), with protein crystalloids, protein fibrils and few starch grains. Nodes 1:2, unilacunar with two leaf traces. Pericycle with hippocrepomorphic sclereids. Crystals acicular?

Trichomes Hairs simple or T-shaped.

Leaves Opposite, simple, entire, with usually conduplicate (in Laurelia involute) ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection? Venation pinnate, brochidodromous. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Lamina often gland-dotted. Idioblasts with ethereal oils abundant. Mucilage cells absent. Leaf margin coarsely serrate.

Inflorescence Axillary, raceme, or flowers solitary axillary.

Flowers Actinomorphic or slightly zygomorphic. Receptacle hollow, expanded into a campanulate or urceolate, lignified hypanthium, enclosing floral parts. Hypogyny to epigyny. Tepals often four to eight (to more than 20; sometimes 4+4), with imbricate aestivation, spiral or almost whorled, free (sometimes reduced or absent); outer tepals sepaloid; inner tepals petaloid; Atherosperma has two outer tepals, completely enclosing bud, and eight inner tepals. Nectaries staminal. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens several to twelve to more than 100, spiral, free from each other and from tepals. Filaments branched or unbranched; outer filaments with two basal scale-like nectariferous glands; inner filaments in Doryphora as sterile staminodia. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, disporangiate, extrorse, dehiscing from base by two longitudinal valves; connective sometimes slightly prolonged; vascular strands of anther glands in Atherosperma running independently of anther strands. Tapetum amoeboid-periplasmodial. Staminodia usually extrastaminal (outer stamens staminodial; in Doryphora intrastaminal).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis modified simultaneous (in ‘Laurelia’ a callose furrow forming at end of meiose I and cytoplasm entirely subdivided at end of meiose II by centrifugally growing cell plates). Pollen grains polar disulcate or meridionosulcate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine semitectate, with columellate infratectum, reticulate.

Gynoecium Carpels three to more than 100, free (apocarpy), spiral; carpel plicate and ascidiate (intermediary), partially postgenitally fused (also occluded by secretion), with a secretory canal; extragynoecial compitum present. Ovary superior to inferior, unilocular. Stylodia lateral or gynobasic, in upper parts connivent into a column, or absent. Stigma papillate, Wet type? Hyperstigma absent. Pistillodia?

Ovules Placentation basal. Ovule one per carpel, anatropous, ascending, with micropylepointing downwards, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Ovular apex exposed. Micropyle ?-stomal. Outer integument two (or three?) cell layers thick. Inner integument approx. three cell layers thick. Archespore unicellular or multicellular. Chalaza? Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development cellular. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit An assemblage of plumose achenes surrounded by lignified urceolate or pyriform hypanthium, usually descending at fruit maturity. Inner staminodia in Atherosperma and Laureliopsis prolonged in fruit.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat? Exotesta? Mesotesta unspecialized, crushed? Endotesta tracheoidal, usually little developed. Tegmen unspecialized, crushed. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, oily. Embryo small to intermediary, straight, well differentiated, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Germination?

Cytology n = 22, 41, 44, 57.

DNA Duplication of PI?

Phytochemistry Insufficiently known. Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, isorhamnetin) and benzylisoquinoline and other alkaloids present. Ellagic acid and proanthocyanidins not found. Aluminium not accumulated.

Use Tea (Atherosperma moschatus), fruits (‘Laurelia’), timber, carpentry.

Systematics Daphnandra (6; D. apetala, D. johnsonii, D. melasmena, D. micrantha, D. repandula, D. tenuipes; eastern Queensland, eastern New South Wales, Tasmania), Doryphora (4; D. aromatica: northerastern Queensland; D. sassafras: northeastern New South Wales, eastern Queensland, D. austrocaledonica: New Caledonia, D. vieillardii: New Caledoniaeastern Queensland, eastern New South Wales, Tasmania), Atherosperma (1; A. moschatum; eastern New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania), Nemuaron (1; N. vieillardii; New Caledonia), Laureliopsis (1; L. philippiana; central and southern Chile from c 45° to 35°S, southern Argentina), ‘Laurelia’ (2; L. novae-zelandiae: New Zealand; L. sempervirens: Peru, Chile; paraphyletic), Dryadodaphne (3; D. crassa: Papua New Guinea, D. novoguineensis: New Guinea, D. trachyphloia: northeastern Queensland).

Atherospermataceae are sister to Gomortega (Gomortegaceae).

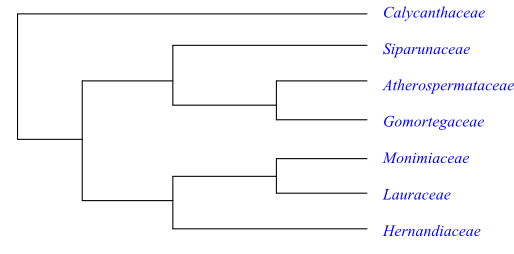

Atherospermataceae comprise six or seven species-poor genera with a disjunct Gondwanan distribution. Fossils confirm the Gondwana origin of the group and also indicate a wide former distribution on the Southern Hemisphere. A molecular phylogeny by Renner & al. (2000) identified three well supported lineages. A clade consisting of Doryphora and Daphnandra (Queensland, New South Wales) may form a sister group to the remaining Atherospermataceae. Atherosperma (eastern Australia, Tasmania) and Nemuaron (New Caledonia) were sisters. Laurelia sempervirens (Chile) was sister to the New Zealand-Chilean clade [Laurelia novae-zelandiae+Laureliopsis philippiana]. Unfortunately, Dryadodaphne was not included in the analysis.

|

Cladogram of Atherospermataceae based on DNA sequence data (Renner & al. 2000). |

CALYCANTHACEAE Lindl. |

( Back to Laurales ) |

Calycanthales Link, Handbuch 2: 71. 4-11 Jul 1829 [‘Calycantheae’]; Chimonanthaceae Perleb, Clav. Class.: 33. Jan-Mar 1838 [‘Chimonantheae’]; Butneriaceae Barnhart in Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 22: 24. 15 Jan 1895 [’Buettneriaceae’] – non Byttneriaceae R. Br. [‘Buttneriaceae’]; Idiospermaceae S. T. Blake in Contr. Queensland Herb. 12: 3. 4 Sep 1972; Calycanthidae C. Y. Wu in Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 40: 292. 2002

Genera/species 4/6–9

Distribution China, Queensland, the United States.

Fossils Virginianthus calycanthoides, from the Early to mid-Albian (113-98 Mya) of Virginia, is assigned to Calycanthaceae with hesitation, but may be even more basal relative to the extant Laurales crown clade. The fossilized flowers bear 30 to 40 stamens with anthers dehiscing by lateral hinged valves, and anamonocolpate pollen grains (resembling Idiospermum) with a reticulate exine and columellate infratectum. Jerseyanthus calycanthoides, from the Turonian of New Jersey, has typical Calycanthaceae pollen and may be sister to Calycanthus. Jerseyanthus possess flowers with 30 to 50 distally petaloid tepals, extrastaminal abaxially curved petaloid staminodia, extrorse anthers, peculiar prolonged connective and inside the androecium c. 24 carpels. The leaf fossil Araipa florifera, with lobate leaves, from the Crato formation of the Early Cretaceous in Brazil (Mohr & Eklund 2003), possess flowers superficially resembling those in Calycanthaceae.

Habit Bisexual (Idiospermum andromonoecious?), evergreen or deciduous trees or shrubs. Bark and often leaves aromatic.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio superficial. Primary stem with four inverted cortical vascular bundles or pericycle, visible as four ridges along stem ([pseudo]siphonostele). Vessel elements with usually simple (rarely scalariform) perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, usually simple (sometimes bordered) pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids or libriform fibres with simple and/or bordered pits, non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate, biseriate or multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma rare (apotracheal diffuse or, in Idiospermum, in tangential bands, or paratracheal scanty, aliform, winged-aliform, vasicentric, or banded) or absent. Tyloses sometimes abundant. Sieve tube plastids Pcsf type with protein crystalloids, protein filaments and few starch grains. Nodes 1:2 (sometimes 1:≥5; in Idiospermum 1:1), unilacunar with usually two leaf traces (sometimes five or more traces; in Idiospermum one). Parenchyma with idioblasts containing ethereal oils. Secretory cells frequent.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular, simple, or absent.

Leaves Opposite, simple, entire, more or less coriaceous, with flat to curved (conduplicate?) ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate. Venation pinnate. Stomata paracytic. Lamina gland-dotted. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Mesophyll with idioblasts containing ethereal oils and often calciumoxalate as single prismatic crystals. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Flowers terminal or axillary, usually solitary (sometimes in terminal, few-flowered cymose inflorescence).

Flowers Actinomorphic. Receptacle an urceolar to calyculate hip-like hypanthium covered by scale-like bracts. Half epigyny. Tepals usually fewer than ten, or (in Idiospermum) c. 15 to c. 40, with imbricate? aestivation, spiral, in hypanthial apex, caducous, free; outermost tepals sepaloid, usually grading into inner petaloid tepals. Nectaries staminodial. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens five to c. 30 (to more than 100), spiral (in Idiospermum often tepaloid), inserted at margin of (and sometimes inside) hypanthium. Filaments short and usually thin, or absent (in Idiospermum flattened), free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, extrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective prolonged. Tapetum secretory. Staminodia ten to c. 25 (to more than 50), intrastaminal (in Idiospermum often tepaloid), nectariferous or with nutritious bodies.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually disulculate (vertically and equatorially; or sometimes trisulculate), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate to semitectate, with columellate infratectum, perforate to finely reticulate, psilate.

Gynoecium Carpels usually one or two (in Idiospermum, rarely three to five), or five to 35(–45), free (apocarpy), spiral, enclosed by receptacle; carpel plicate and ascidiate, postgenitally completely fused, without canal; extragynoecial compitum (formed by stigmas) present in Idiospermum, Chimonanthus and Sinocalycanthus. Ovary semi-inferior, unilocular (apocarpy). Most carpels enclosing two lateral ovules. Stylodia usually long, narrow (in Idiospermum very short or absent). Stigma usually decurrent (in Idiospermum obliquely terminal), usually non-papillate (in Idiospermum fleshy and hairy), Dry type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation basal to marginal. Ovule usually one (ovules rarely two, upper one degenerating) per carpel, anatropous, ascending, apotropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar or pseudocrassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal (in Chimonanthus and Sinocalycanthus?) or bistomal (in Idiospermum and Calycanthus). Outer integument usually five or six (rarely seven or eight), or, in Idiospermum, twelve to 15 cell layers thick. Inner integument four or five cell layers thick. Ovular apex sometimes exposed. Chalaza? Nucellar cap present (Calycanthus). Nucellar beak present in Idiospermum. Megagametophyte monosporous, variation of Polygonum type. Polar nuclei not fusing. Antipodal cells two. Endosperm development cellular (triple fusion not occurring during fertilization at least in Calycanthus occidentalis, endosperm developing independently; in other Calycanthaceae?). Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit An assemblage of achenes surrounded by fleshy enlarged hypanthium.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat testal. Testa usually multiplicative (not in Idiospermum). Exotestal cells cuboid, somewhat lignified. Mesotesta unspecialized, crushed (in Idiospermum?). Endotesta tracheidal, with more or less lignified cell walls (in Idiospermum?). Tegmen unspecialized, crushed (in Idiospermum?). Perisperm not developed. Endosperm absent. Embryo large, well differentiated, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons usually two (in Idiospermum three or usually four), usually spirally twisted and convolute (in Idiospermum massive, peltate). Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 11 (occasionally 12) – Isozyme duplication in Calycanthus indicates paleopolyploidy.

DNA Nuclear gene PI duplicated. Mitochondrial intron coxII.i3 lost (Calycanthus).

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin; not found in Idiospermum), flavone glycosides, luteolin, mono- and sesquiterpenes (very abundant), benzylisoquinoline alkaloids, indole alkaloids (calycanthidine, calycanthine, chimonanthine, folicanthine, etc.; in seeds of Calycanthus and very toxic to mammals), piperidinoindoline and pyrrolidinoindoline alkaloids (idiospermine, idiospermamine, idiospermuline, etc.; in Idiospermum), and tyrosine derived cyanogenic compounds present. Ellagic acid, condensed tannins and proanthocyanidins not found.

Use Ornamental plants, spices (Calycanthus), medicinal plants.

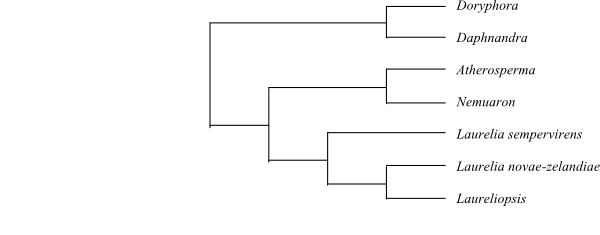

Systematics Calycanthaceae are sister-group (with very high support) to the remaining Laurales.

Idiospermoideae (Blake) Thorne in Aliso 8: 175. 9 Sep 1974

Idiospermum (1; I. australiense; the Daintree Rainforest in northeastern Queensland). – Apotracheal axial parenchyma in tangential bands. Nodes 1:1. Tepals numerous (c. 15–40). Stamens and staminodia often tepaloid. Carpels one or two (to five). Inner carpels often ascidiate for most of their length. Stylodia absent or almost so. Stigma obliquely terminal, short, fleshy and hairy. Micropyle bistomal. Outer integument 12–15 cell layers thick. Nucellar beak present. Testa not multiplicative. Cotyledons three or four, massive and peltate. Flavone glycosides, C-glycosylflavone, piperidinoindoline and pyrrolidinoindoline alkaloids (idiospermine, idiospermamine, idiospermuline, etc.) present. Myricetin, flavonoid sulphates and proanthocyanins not found. – Idiospermum is sister to the remaining Calycanthaceae.

Calycanthoideae Burnett, Outlines Bot.: 710, 1092, 1135. Feb 1835 [‘Calycanthidae’]

3/6–9. Calycanthus (2; C. floridus: southeastern United States; C. occidentalis: California, Oregon), Sinocalycanthus (1; S. chinensis; northern Zhejiang in China), Chimonanthus (3–6; C. campanulatus, C. grammatus, C. nitens, C. praecox, C. salicifolius, C. zhejiangensis; central and eastern China). – Nodes 1:2(≥5). Tepals usually fewer than ten. Carpels five to 35 (to c. 45). Stigmas filiform. Micropyle usually endostomal. Cotyledons usually twisted, convolute.

|

Cladogram of Calycanthaceae based on DNA sequence data (Renner 1999). |

GOMORTEGACEAE Reiche |

( Back to Laurales ) |

Genera/species 1/1

Distribution Central Chile.

Fossils Uncertain. Lovellea wintonensis, from Upper Albian layers (the Winton Formation) in western Queensland, a floral fossil with cup-shaped receptacle, plausibly represents the oldest known remnants of Gomortegaceae. Perianth and stamens are borne on the margin and numerous carpels are embedded in the wall, with upper part of the long tapering styles free. Unicellular hairs are inserted on the inner surface and directed upwards towards the orifice. The stamens with introrse valvicidal anthers occur in two whorls. The pollen grains are disulcate and have a retitectate exine. Each carpel has a single laterally inserted bitegmic ovule. The endotestal cells are crystalliferous.

Habit Bisexual, evergreen tree. Aromatic. Young branches quadrangular in transverse section.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio superficial. Primary stem with separate vascular bundles. Vessel elements elongate, thin-walled, with usually scalariform (in young wood often simple) perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform, opposite or alternate, simple pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids with bordered pits, non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse. Secondary phloem in upper part with expanding wood rays. Sieve tube plastids Pcsf type with few protein crystalloids and protein fibrils, and single starch grains. Nodes 1:2, unilacunar with two leaf traces. Parenchyma in stem, branches and leaves with secretory cavities containing a yellowish resinous substance. Pericycle with hippocrepomorphic sclereids? Mucilage cells absent. Crystals acicular?

Trichomes Hairs simple.

Leaves Opposite, simple, entire, coriaceous, with ? ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundles? Venation pinnate. Stomata paracytic. Lamina gland-dotted. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Mesophyll with idioblasts containing ethereal oils. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, racemose. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) two, small, caducous.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Hypanthium absent. Epigyny. Tepals five to seven (to ten), spiral to almost whorled, sepaloid, free. Nectaries staminal. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens (two to) seven to 13, spiral; outermost one to three stamens petaloid (extrastaminal), often nearly sterile (staminodia with incompletely developed microsporangia); intermediate five to ten staminal filaments with two basal nectariferous glands; innermost one to three stamens often sterile intrastaminal staminodia. Filaments relatively thin, free from one another and from tepals. Anthers disporangiate, introrse (outer stamens) or latrorse (intermediate stamens), dehiscing from base by two longitudinal apically hinged valves. Tapetum secretory, with binucleate cells. Staminodia extrastaminal (outer stamens staminodial) or absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains inaperturate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, reduced, with intermediary infratectum, and beset with small supratectal spinules.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (two or) three (to five) connate carpels; carpel plicate or ascoplicate, postgenitally fused, without canal. Ovary inferior, usually trilocular (sometimes bi-, quadri- or quinquelocular). Style single, simple, very short. Stigma with usually two (rarely three) upright lobes, papillate, Dry type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation apical, with oblique insertion on funicle. Ovule one per carpel, hemianatropous (almost orthotropous), pendulous, apotropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle bistomal. Outer integument two or three cell layers thick. Inner integument four cell layers thick. Endothelium not produced. Ovule pachychalazal. Chalaza unspecialized. Nucellar cap two to four cell layers thick. Obturator absent. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development cellular. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A one-seeded drupe.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat exotestal. Exotesta well developed. Mesotesta little developed or absent. Endotesta tracheoidal, little developed. Tegmen unspecialized, crushed? Hypostase produced. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, oily. Embryo large, straight, well differentiated, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Germination?

Cytology n = 21 – Paleohexaploidy?

DNA Duplication of PI?

Phytochemistry Very insufficiently known. Flavonols (isorhamnetin)? Alkaloids?

Use Fruits, timber.

Systematics Gomortega (1; G. nitida; central Chile) is sister to Atherospermataceae.

HERNANDIACEAE Blume |

( Back to Laurales ) |

Hernandiales Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 235. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Hernandiae’]; Gyrocarpaceae Dumort., Anal. Fam. Plant.: 13, 14. 1829 [’Gyrocarpeae’]; Gyrocarpales Dumort., Anal. Fam. Plant.: 13. 1829 [’Gyrocarparieae’]; Illigeraceae Blume, Nov. Plant. Expos.: 12. Aug-Dec 1833 [‘Illigereae’]; Illigerales Blume in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp. Regn. Veg.: 15. Sep-Oct 1835 [‘Illigereae’]

Genera/species 4/c 70

Distribution Hernandioideae: pantropical, with the largest diversity in Madagascar and in Southeast Asia and Malesia; Gyrocarpoideae: tropical and subtropical regions, particularly in coastal areas and also on oceanic islands: eastern and southern India, Sri Lanka, Indochina, parts of Malesia, northern Australia, with the highest diversity in Central America and northern South America.

Fossils Uncertain.

Habit Bisexual, monoecious, andromonoecious, polygamomonoecious, or dioecious, evergreen trees, shrubs or lianas. Aromatic.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio superficial. Primary vascular tissue a cylinder; separate vascular bundles absent. Vessel elements with simple perforation plates; lateral pits usually alternate, simple pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids (Gyrocarpoideae) or libriform fibres (Hernandioideae) with simple or bordered pits, non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma usually paratracheal scanty vasicentric, aliform or lozenge-aliform. Wood elements sometimes storied. Sieve tube plastids Psc type (PIb type), with less than ten starch grains. Nodes 1:1–2(–7?), unilacunar with one or two (to seven?) leaf traces. Pericycle with hippocrepomorphic sclereids? Cystoliths present in Gyrocarpus and Sparattanthelium. Crystals?

Trichomes Hairs unicellular, simple, often with an apical hook. Foliar glandular hairs in Hernandia and Illigera sunken in epidermis.

Leaves Alternate (spiral), palmately compound or simple, entire or trilobate, with ? ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection horizontally (some species of Hernandia) or vertically elliptic. Venation palmate, triplinerved to camptodromous or pedate. Stomata paracytic (Hernandioideae) or anomocytic (Gyrocarpoideae). Cuticular wax crystalloids? Mesophyll with idioblasts containing ethereal oils. Secretory cavities with mucilage (mucilage cells) or oils present (Hernandioideae) or absent (Gyrocarpoideae). Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal, corymb, panicle or compound thyrse (in Hernandia flowers of first and second order in each cyme male and flower of third order female); in Gyrocarpoideae dense thyrse.

Flowers Actinomorphic. Hypanthium absent. Epigyny. Tepals three to ten, with imbricate or valvate aestivation, sepaloid, sometimes persistent, whorled, in one series with (two to) four to eight (Gyrocarpoideae), or in two series each with three to five (to seven) (Hernandioideae), free. Nectaries extrastaminal or absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens three to five (to seven) in a single whorl. Filaments free from each other and from tepals, usually with one or two extrastaminal dorsibasal or basilateral nectariferous glands (staminodia). Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, disporangiate, latrorse, dehiscing from base by longitudinal apically or laterally hinged valves. Tapetum in at least Gyrocarpoideae amoeboid-periplasmodial. Staminodia in some species of Gyrocarpoideae three to seven, in one or two outer whorls.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis at least in Gyrocarpoideae successive. Pollen grains inaperturate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine almost intectate (indistinct and very thin), with granular acolumellate infratectum, and beset with supratectal spines and globuli. Intine usually thick to very thick.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of one carpel (monocarpellate), usually abaxially directed; carpel plicate or ascidiate (to ascoplicate), postgenitally fused, without canal. Ovary inferior, unilocular. Style single, simple, with a ventral furrow running downwards from stigma. Stigma peltate, papillate, Dry type. Male flowers often with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation apical (Hernandioideae) or marginal (Gyrocarpoideae). Ovule one per ovary, anatropous, pendulous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal?, directed upwards. Outer integument nine to 23 cell layers thick. Inner integument three to eight cell layers thick. Ovule sometimes pachychalazal. Nucellar beak present in Hernandioideae. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Hypostase absent. Endosperm development ab initio cellular. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit Usually a drupe with massive endocarp (in Gyrocarpus and Illigera a samara with wings formed from ovary; in Hernandia surrounded by bracts often forming a cupule).

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat testal. Testa at least usually vascularized and multiplicative. Mesotesta spongy. Endotesta in Hernandioideae unspecialized; endotesta in Gyrocarpoideae tracheidal, with more or less lignified cell walls. Tegmen unspecialized, early crushed. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm absent. Embryo large, straight, in Gyrocarpus and Sparattanthelium contortuplicate (much folded), chlorophyll? Cotyledons two, fleshy, oily, convolute. Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = 10, 20, 30 (Hernandioideae); n = 15, 24, 48 (Gyrocarpoideae) – Polyploidy occurring.

DNA Duplication of PI?

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), O-glycosylated flavonoids, benzylisoquinoline alkaloids, polyacetate derived anthraquinones?, lignans (of furfurane, dibenzoylbutyrolactone and podophyllotoxin type), and ethereal oils (particularly perrillar aldehyde) present. Aluminium not accumulated. Ellagic acid and proanthocyanidins not found.

Use Ornamental trees, timber.

Systematics Hernandiaceae may be sister to either Lauraceae or Monimiaceae, or to a clade consisting of these two groups.

Hernandioideae Endl. ex Miq., Fl. Ned. Ind. 1(1): 886. 19 Aug 1858 [’Hernandiaceae’]

2/c 50. Hernandia (>30; tropical regions, with their largest diversity in tropical Asia to southwestern Pacific), Illigera (18; tropical regions in the Old World). – Pantropical. Trees (Hernandia) or lianas (Illigera). Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform fibres. Cystoliths absent. Nodes 1:3(–7?). Leaves in Illigera palmately compound. Stomata paracytic. Foliar epidermis with sunken glandular hairs. Secretory cavities with mucilage (mucilage cells) or oils present. Inflorescence thyrsoid. Tepals in two whorls. Anther valves sometimes laterally hinged. Tapetal cells radially elongated. Single layer of microspore mother cells. Pollen grains 90–160 μm in diameter. Placentation apical. Outer integument ten to 23 cell layers thick. Megasporangium massive, with parietal cells in six to eight layers. Nucellar beak present. Floral prophylls usually accrescent in fruit (not in Illigera). Seeds ruminate (in Hernandia). Testa vascularized, spongy, tanniniferous; mesotesta massive, seven to 17 cell layers thick; endotesta unspecialized. Testal cell walls in Hernandia not thickened. n = 10, 20, 30.

Gyrocarpoideae J. Williams in J. H. Balfour, Man. Bot., ed. 3: 425. 1855 [‘Gyrocarpeae’]

2/19. Gyrocarpus (5; G. americanus, G. angustifolius, G. hababensis, G. jatrophifolius, G. mocinnoi; tropical and subtropical regions on both hemispheres), Sparattanthelium (14; tropical South America). – Tropical and subtropical regions. Trees (Gyrocarpus) or hooked lianas (Sparattanthelium). Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids. Stem (including wood) and leaves with cystoliths. Nodes 1:2. Stomata anomocytic. Secretory mucilage or oil cavities absent. Inflorescence dichasial, ebracteate. Tepals in one whorl. Pollen grains 19–45 μm in diameter. Placentation marginal. Apical part of megagametophyte protruding from the megasporangium. Endotesta tracheidal; endotestal cells radially elongated, with spiral thickenings (Gyrocarpus). Cotyledons contortuplicate. n = 15, 24, 48.

|

Cladogram of Hernandiaceae based on DNA sequence data (Renner 1999; Renner & Chanderbali 2000). |

LAURACEAE Juss. |

( Back to Laurales ) |

Cassythaceae Bartl. ex Lindl., Nix. Plant.: 15. 17 Sep 1833 [‘Cassytheae’], nom. cons.; Perseaceae Horan., Prim. Lin. Syst. Nat.: 61. 2 Nov 1834 [’Perseaceae. (Laurinae)’]

Genera/species c 45/2.475–2.515

Distribution Tropical and subtropical regions, with their largest diversity in Southeast Asia and tropical America, and a few genera in temperate areas.

Fossils Potomacanthus lobatus, from the Early to mid-Albian of Virginia, represents the oldest known fossil Lauraceae, a bisexual trimerous flower with tepals and stamens each in two whorls and a monocarpellate ovary with a single ovule in the ascidiate-plicate carpel. Mauldinia is a number of Cenomanian to Late Santonian inflorescences and trimerous flowers found in several places in Europe, Central Asia and North America. The petals are inserted in two whorls and the stamens in three fertile whorls and one staminodial whorl, and the gynoecium consists of a single uniovular carpel. Pragocladus lauroides, from the mid-Cenomanian of the Czech Republic, bore bisexual trimerous flowers – similar to Mauldinia – in a compound spike-like inflorescence. Neusenia tetrasporangiata (Early Campanian of North Carolina), Lauranthus futabensis (Early Coniacian of Japan) and Perseanthus crossmanensis (Turonian of New Jersey), are three more trimerous and mostly bisexual flowers, which strongly resemble Mauldinia. Wood and leaves of presumed lauraceous origin have been described from both Early and Late Cretaceous layers (e.g. the Santonian-Maastrichtian Sassafrasoxylon gottwaldii from the Antarctic Peninsula) and the Cenozoic fossil record of Lauraceae is very rich and diverse.

Habit Bisexual, monoecious, polygamomonoecious or dioecious, usually evergreen (rarely deciduous) trees or shrubs. Aromatic. Cassytha consists of parasitic, climbing herbs with more or less photosynthesizing stems.

Vegetative anatomy Cassytha with haustoria on stems and branches, without mycorrhiza. Phellogen ab initio usually superficial (in Cinnamomum pericyclic; in Cassytha absent?). Primary vascular tissue a cylinder; separate vascular bundles absent. Vessel elements with usually simple (sometimes also scalariform) perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, simple and/or bordered pits. Vestured pits present (e.g. Sassafras) or absent. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids, fibre tracheids or libriform fibres with simple pits, septate or non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma usually paratracheal scanty, aliform, lozenge-aliform, winged-aliform, confluent, vasicentric, unilateral, or banded (sometimes apotracheal diffuse). Wood elements often storied. Wood often fluorescent. Tyloses often common (sometimes sclerotic). Secondary phloem sometimes stratified into hard fibrous and soft parenchymatous layers. Sieve tube plastids usually Psc type (PIb type), with fewer than ten starch grains (rarely S type, with ten or fewer starch grains). Nodes 1:1–3, unilacunar with one to three leaf traces. Pericycle with hippocrepomorphic sclereids? Silica bodies present in some species. Prismatic or acicular calciumoxalate crystals, styloids and crystal sand sometimes present.

Trichomes Hairs usually unicellular, simple, thick-walled, or absent.

Leaves Usually alternate (rarely opposite or verticillate), simple, usually entire (rarely lobed; in Cassytha small, scale-like), often coriaceous, with conduplicate or supervolute ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate. Venation usually pinnate (rarely palmate). Stomata usually paracytic (sometimes anomocytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids as transversely ridged rodlets (Aristolochia type), chemically dominated by palmitone. Domatia (as hair tufts or pockets, also acarodomatia) present in axils of abaxial veins in some genera. Lamina usually gland-dotted. Mesophyll usually with idioblasts containing ethereal oils; mucilaginous idioblasts present in some genera. Secretory cavities absent. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Usually axillary (sometimes terminal), umbel-like to thyrsoid (rarely capitate or raceme-like; flowers rarely solitary), in fruit often with large involucrate and often accrescent bracts.

Flowers Actinomorphic, usually small. Receptacle expanded into a cupular, campanulate or urceolate hypanthium, surrounding floral parts. Usually hypogyny (sometimes half epigyny; in Hypodaphnis epigyny). Tepals usually 3+3(+3) (sometimes 2+2[+2]; flowers in Potameia dimerous), with imbricate aestivation, whorled, sepaloid or petaloid (in some genera tepals may be modified stamens), persistent (and sometimes accrescent) or caducous, or absent. Nectaries staminal or absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens (three to) nine (to 26), usually in multiples of three, usually in four whorls, occasionally somewhat foliaceous to petaloid; first and second staminal whorls with introrse anthers; third whorl with extrorse to introrse anthers, and filaments often with two basal nectariferous glands; innermost staminal whorl sterile or absent (inner two or three whorls in some genera staminodial or absent). Filaments free or connate at base, free from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, with widely separated thecae, disporangiate or tetrasporangiate, usually introrse (sometimes varying within a flower), usually dehiscing from base by two or four longitudinal hinged valves (sometimes poricidal; in Cassytha extrorse, dehiscing by longitudinal valves); connective sometimes slightly expanded. Tapetum usually amoeboid-periplasmodial, with usually binucleate (sometimes quadrinucleate) cells (in Cassytha etc. secretory). Staminodia intrastaminal or absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains inaperturate or dicolpate (with diffuse apertures), shed as monads, usually bicellular at dispersal (in at least Beilschmiedia often tricellular). Exine extremely thin, usually acolumellate, with granular infratectum, usually echinate (sometimes verrucate, rugulate or spinulate), striate. Pollen grains in ‘Dahlgrenodendron’ with well developed columellate exine. Intine usually thick to very thick.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of one carpel (monocarpellate?, perhaps in reality three carpels, two of which aborting); carpel plicate or ascoplicate, postgenitally fused, without canal. Ovary usually superior (sometimes semi-inferior, rarely inferior), unilocular. Stylodium single, often with deep ventral furrow, or absent. Stigma capitate, discoid, lobate or decurrent, papillate, Dry type. Male flowers often with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation apical or subapical. Ovule one per ovary, anatropous, pendulous, apotropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle usually endostomal (in Cassytha bistomal). Outer integument four to eleven cell layers thick. Inner integument three to ? cell layers thick. Archespore usually unicellular (in Cassytha multicellular). Nucellar cap usually present (absent in Cassytha). Chalaza pachychalazal. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type; megagametophyte often prolonged and protruding through micropyle. Synergids usually with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells four, usually non-proliferating, or three antipodal nuclei early degenerating. Hypostase usually absent (present in some genera). Endosperm development usually nuclear (in Cassytha cellular). Endosperm haustoria micropylar (Cryptocarya; absent in Cassytha etc.). Embryogenesis onagrad, asterad, piperad or undefined.

Fruit Usually a one-seeded berry or a berry-like drupe with thin endocarp. Fruit stalk and receptacle often widened and coloured or forming a fleshy to woody cupule around fruit base or surrounding entire fruit (hence resembling an acorn).

Seeds Aril absent. Seeds ruminate. Seed coat endotestal. Testa usually thin (in Cassytha thick and coarse), vascularized and multiplicative. Mesotesta unspecialized, crushed. Endotestal cells tracheidal, with lignified cell walls, longitudinally or transversally elongate. Tegmen unspecialized, early crushed. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm absent. Multiseriate massive suspensor present. Embryo large, straight, well differentiated, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, large (rarely ruminate; in Cassytha and Ravensara connate). Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = 12 (15, 24, 36) – Isozyme duplications indicate paleopolyploidy.

DNA The nuclear gene PI is duplicated.

Phytochemistry 5-O-methylflavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, isorhamnetin), flavones, proanthocyanidins, benzylisoquinoline alkaloids, indole alkaloids (tryptamines) and other alkaloids, lignans, neolignans, polyketides (acetogenins), and nitrophenyl ethan present. Ellagic acid not found. Inulin? Aluminium accumulated in some species in the Perseeae-Laureae clade.

Use Ornamental plants, fruits (Persea americana), spices and flavours (Cinnamomum, Laurus nobilis), medicinal plants (Cinnamomum camphora, Litsea), oils (Persea, Sassafras), timber.

Systematics Hypodaphnis (1; H. zenkeri; tropical West and Central Africa); Cryptocarya (c 370; tropical and subtropical regions on both hemispheres), Eusideroxylon (1; E. zwageri; Sumatra, Borneo), Potoxylon (1; P. melagangai; Borneo), Aspidostemon (c 30; Madagascar), Dahlgrenodendron (1; D. natalense; the southern Natal/Pondoland sandstone area in South Africa), Beilschmiedia (c 290; tropical and subtropical regions on both hemispheres; incl. Endiandra?), Endiandra (c 125; Malesia to tropical Australia, New Caledonia, Fiji; in Beilschmiedia?); Caryodaphnopsis (16; East and Southeast Asia, southern United States, Mexico, Central America, tropical South America), Cassytha (c 20; tropical and subtropical regions in the Old World, with their largest diversity in Australia), Neocinnamomum (4; N. caudatum, N. delavayi, N. lecomtei, N. mekongense; southern China, Southeast Asia); Chlorocardium (2; C. rodiei, C. venenosum; tropical South America), Anaueria (1; A. brasiliensis; Amazonas), Williamodendron (4; W. cinnamomeum, W. glaucophyllum, W. quadrilocellatum, W. spectabile; Brazil), Mezilaurus (c 20; Costa Rica to tropical South America), Sextonia (2; S. pubescens, S. rubra; tropical South America), Sassafras (3; S. tzumu: central and southwestern China; S. randaiense: Taiwan; S. albidum: southeastern Canada, eastern and central United States); ‘Phoebe’ (c 50; India, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, Malesia; polyphyletic), Persea (c 120; Macaronesia, tropical and subtropical regions in Asia and America; incl. Alseodaphne?), Alseodaphne (55–60; India, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, Malesia; in Persea?), Laurus (2–3; L. nobilis: the Mediterranean; L. azorica, L. novocariensis: Macaronesia), Dodecadenia (1; D. grandiflora; southern Himalayas), ’Lindera’ (50–55; temperate to tropical regions in Asia and Australia, eastern North America; polyphyletic), ’Actinodaphne’ (c 35; India, Sri Lanka, East and Southeast Asia, Malesia; polyphyletic), ’Neolitsea’ (c 60; India, Sri Lanka, East and Southeast Asia, Malesia to tropical Australia; polyphyletic), ’Litsea’ (c 135; Madagascar, tropical and subtropical Asia to Japan, New Guinea, northern and eastern Australia and islands in southwestern Pacific, southeastern United States, Mexico, Central America; polyphyletic), Cinnamomum (340–350; Cameroon, East and Southeast Asia, Malesia to Australia, Fiji and Samoa, southern California, Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America), Umbellularia (1; U. californica; western North America), ‘Ocotea’ (425–430; Macaronesia, tropical and southern Africa, Madagascar, the Mascarene Islands, tropical and subtropical America; non-monophyletic), Aniba (c 50; the Andes in Colombia to Bolivia), Dicypellium (2; D. caryophyllatum, D. manausense; eastern Amazonas), Kubitzkia (2; K. macrantha, K. mezii; northeastern South America), Licaria (c 40; Central America, tropical South America), Phyllostemonodaphne (1; P. geminiflora; southeastern Brazil), Pleurothyrium (35–40; Central America, western tropical South America), Paraia (1; P. bracteata; Amazonas), ‘Nectandra’ (115–120; tropical South America; non-monophyletic), Damburneya (c 20; Florida, Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, northern South America), Endlicheria (c 60; the West Indies, tropical South America), Rhodostemonodaphne (c 35; tropical South America). – Unplaced Lauraceae: Apollonias (1; A. barbujana; Macaronesia except Cape Verde Islands), Cinnadenia (2; C. malayana, C. paniculata; Bhutan, Assam, Burma, the Malay Peninsula), Dehaasia (c 35; Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea), Micropora (1; M. curtisii; the Malay Peninsula), Urbanodendron (3; U. bahiense, U. macrophyllum, U. verrucosum; eastern Brazil). – Generic delimitations are very problematic.

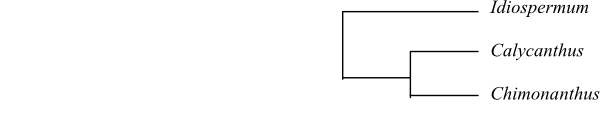

In the molecular analysis of c. 35 genera by Chanderbali & al. (2001), the most basal clade has the following topology: [Hypodaphnis+[[Cryptocarya+[Beilschmiedia+Endiandra+Potameia]]+ Aspidostemon+[Potoxylon+Eusideroxylon]]]. This clade has a secretory (glandular) anther tapetum and a megagametophyte protruding from the megasporangium (Kimoto & al. 2006). Hypodaphnis zenkeri – sometimes identified as sister to the other Lauraceae – is epigynous, has tetrasporangiate anthers, lack staminodia and may have anomocytic stomata (or the subsidiary cells enclose the guard cells). The next clade consists of [Caryodaphnopsis+[Cassytha+Neocinnamomum]]. This second clade also has a protruding megagametophyte.

|

Parsimony strict consensus tree (simplified) of Lauraceae based on DNA sequence data (Chanderbali & al. 2001). Apollonias may belong in the Persea-Alseodaphne clade. Hypodaphnis is sometimes recovered as sister to the remaining Lauraceae. |

MONIMIACEAE Juss. |

( Back to Laurales ) |

Genera/species 24–26/c 280?

Distribution Central and East Africa, Sri Lanka, Malesia, eastern Australia, Melanesia, New Zealand, tropical and subtropical regions in Central and South America, with their largest diversity in Madagascar, Malesia, on islands in the southwestern Indian Ocean, and in South America.

Fossils Several species of Hedycaryoxylon, comprising fossil wood, have been described from the Early Senonian to the Cenozoic of Europe, South Africa and Antarctica. Fossilized leaves and pollen grains of Monimiaceae are also known.

Habit Monoecious, andromonoecious, gynomonoecious, polygamomonoecious, dioecious, androdioecious, or polygamodioecious (in Hortonia bisexual), evergreen trees or shrubs (Palmeria consists of lianas). Often aromatic.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio superficial. Primary stem with vascular tissue a cylinder or consisting of separate vascular bundles. Vessel elements with usually scalariform (sometimes reticulate; in, e.g., Monimia, Palmeria and Peumus also simple) perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform, alternate or opposite, simple pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids or often fibre tracheids or libriform fibres with simple and/or bordered pits, septate or non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse, or paratracheal scanty, or absent. Tyloses often abundant. Secondary phloem often with glimmering rays. Sieve tube plastids S type, with approx. ten starch grains, or Psc type, with protein crystalloids and ten to 15 starch grains. Sieve tube nuclei with rosette-shaped non-dispersive protein bodies. Nodes 1:1–7, unilacunar with one to seven leaf traces. Pericycle with hippocrepomorphic sclereids. Crystal sand present in some species.

Trichomes Foliar hairs unicellular or multicellular, simple, furcate, stellate, peltate, lepidote, or absent.

Leaves Usually opposite (rarely verticillate three to seven together), simple, entire, often coriaceous, with conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate? Venation usually brochidodromous and festoon-shaped, with secondary veins almost always arising at regular angle and intervals (in Hortonia palmate). Stomata paracytic or anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Lamina often gland-dotted. Domatia, as pockets, present in Tetrasynandra. Secretory cavities with resins present or absent. Mesophyll with idioblasts containing ethereal oils. Mucilage cells absent. Leaf margin usually serrate, with monimioid teeth (one vein proceeding into opaque persistent glandular cap on tooth; in Monimioideae entire).

Inflorescence Usually axillary or (seemingly) terminal, cymose (helicoids, etc.) (flowers rarely solitary, axillary).

Flowers Actinomorphic or slightly zygomorphic, usually small. Receptacle hollow, enlarged into a cupulate, campanulate or urceolate hypanthium enclosing floral parts (receptacle of male flowers reduced in Levieria and Xymalos; hypanthium in some genera closed by a ‘roof’ opening at anthesis). Usually half epigyny (in Tambourissa epigyny). Tepals (three or) 2+2 to more than 50, spiral or whorled, with usually imbricate (rarely decussate) aestivation, sepaloid, petaloid or calyptrate (with bud apex caducous like a calyptra; inner tepals in Hortonia and Peumus petaloid), usually free, or absent. Nectaries staminal or absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens eight to more than 150 (to more than 1.800 in Tambourissa), spiral or whorled. Filaments usually free (in Tetrasynandra connate at base), free from tepals. Paired nectariferous glands usually absent (fertile outer filaments in Hortonia, Monimia and Peumus with two basal nectariferous glands; intrastaminal? staminodia present in Hortonia and Peumus). Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (in Monimia transversally disporangiate), extrorse or introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits; in Hennecartia by transversal hinged valves). Tapetum secretory. Female flowers often with staminodia.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous or successive. Pollen grains inaperturate, usually shed as monads (in Kibaropsis and some species of ‘Hedycarya’ as acalymmate tetrads), bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or intectate, with intermediary or no infratectum, microperforate or imperforate, wrinkled, spinulate, echinate or with echinulate-stellate supratectal processes. Intine usually thin. Pollen grains in Hortonia with spirally twisted hollow sexine strands and thick intine with tangentially arranged canals.

Gynoecium Carpels usually numerous (sometimes few; in Xymalos one; Decaryodendron with up to c. 1.000 and Tambourissa up to c. 2.000 carpels in a single flower), whorled, free (apocarpy); carpel plicate and ascidiate (intermediary), partially postgenitally fused, with secretory canal (carpels in Mollinedia ascidiate, at first open, later occluded by secretion); extragynoecial compitum sometimes present. Carpels in Faika, Hennecartia, Kibara, Tambourissa, and Wilkiea enclosed in a floral cup apically open by a pore, a hyperstigma (pollen grains germinate into pore by secretion from minute tepals, pollen tubes growing through a line of secretion into floral cup thus reaching stigmas from inside). Ovary usually semi-inferior (in Tambourissa inferior), unilocular. Stylodia single, simple, long or short. Stigma papillate, Dry type. Hyperstigma (appendage above stigma) present in Tambourissa, Kibara, Wilkiea and Hennecartia. Pistillodia?

Ovules Placentation apical. Ovule one per carpel, usually anatropous (in Kibaropsis hemianatropous), usually ascending (rarely pendulous), bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle usually endostomal (sometimes bistomal), erect (in Kibaropsis lateral). Outer integument two to five cell layers thick. Inner integument at least three cell layers thick. Obturator usually present. Megagametophyte usually monosporous, Polygonum type (seemingly Allium type). Antipodal cells at least sometimes proliferating (up to five to c. 20 cells). Hypostase present at least in some genera. Endosperm development cellular. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis asterad.

Fruit A head-like cluster of drupelets, often more or less connate into a secondary drupaceous syncarp, with fleshy appendages, usually surrounded by often fleshy hypanthium and/or receptacle, together forming a pseudofruit, at maturation dehiscing by longitudinal slits or by an operculum.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat endotestal?, with or without tracheids. Exotesta unspecialized? Mesotesta unspecialized, crushed. Endotesta tracheidal, with lignified cell walls. Tegmen unspecialized, finally crushed. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, oily. Embryo short to relatively long, straight, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons usually two (in Kibaropsis four). Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 19–22, 39, 43, 57 or more – Polyploidy occurring in some genera.

DNA Duplication of PI?

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, isorhamnetin), cyanidin, proanthocyanidins, and benzylisoquinoline and other alkaloids present. Ellagic acid not found. Aluminium sometimes accumulated.

Use Medicinal plants (Peumus), timber.

Systematics Monimia (3; M. amplexicaulis: Réunion; M. rotundifolia: Réunion; M. ovalifolia: Mauritius, Réunion), Palmeria (15–20?; New Guinea, eastern Queensland, eastern New South Wales, Victoria), Peumus (1; P. boldus; southern Peru, central Chile, central Argentina); Lauterbachia (1; L. novoguineensis; New Guinea), Macrotorus (1; M. utriculatus; southeastern Brazil), Hortonia (2; H. angustifolia, H. floribunda; Sri Lanka), Austromatthaea (1; A. elegans; northeastern Queensland), Decarydendron (4; D. helenae, D. lamii, D. perrieri, D. ranomafanensis; Madagascar), Ephippiandra (7; E. domatiata, E. madagascariensis, E. masoalensis, E. microphylla, E. myrtoidea, E. perrieri, E. tsaratanensis; Madagascar), Faika (1; F. villosa; western New Guinea), Grazielanthus (1; G. arkeocarpus; southeastern Brazil), ’Hedycarya’ (c 30?; Sulawesi to New Guinea, eastern Queensland, eastern New South Wales, Victoria, King Island, New Caledonia, Fiji, New Zealand; paraphyletic; incl. Kibaropsis and Levieria?), Kibaropsis (1; K. caledonica; New Caledonia; in Hedycarya?), Levieria (7; L. acuminata, L. beccariana, L. montana, L. nitens, L. orientalis, L. scandens, L. squarrosa; Sulawesi to eastern Queensland; in Hedycarya?), Hennecartia (1; H. omphalandra; southern Brazil, Paraguay, northeastern Argentina), Kairoa (2; K. endressiana, K. suberosa; Papua New Guinea), Kibara (43; Nicobar Islands, Malesia to tropical Australia), Macropeplus (4; M. dentatus, M. friburgensis, M. ligustrinus, M. schwackeanus; eastern Brazil), Matthaea (6; M. chartacea, M. heterophylla, M. intermedia, M. pubescens, M. sancta, M. vidalii; Malesia), Mollinedia (c 90?; southern Mexico, Central America, tropical South America), Parakibara (1; P. clavigera; the Moluccas), Steganthera (c 30; East Malesia to New Guinea and Solomon Islands, northeastern Queensland), Tambourissa (18; Madagascar, the Mascarene Islands), Tetrasynandra (3; T. laxiflora, T. longipes, T.pubescens; northeastern Queensland), Wilkiea (8; eastern Papua New Guinea, eastern Queensland, eastern New South Wales), Xymalos (1; X. monospora; East and southern Africa).

Monimiaceae are either sister-group to Hernandiaceae or Lauraceae, or to a clade consisting of these two groups. Romanov & al. (2007) emphasize the similarities in fruit morphology between Monimiaceae and Lauraceae.

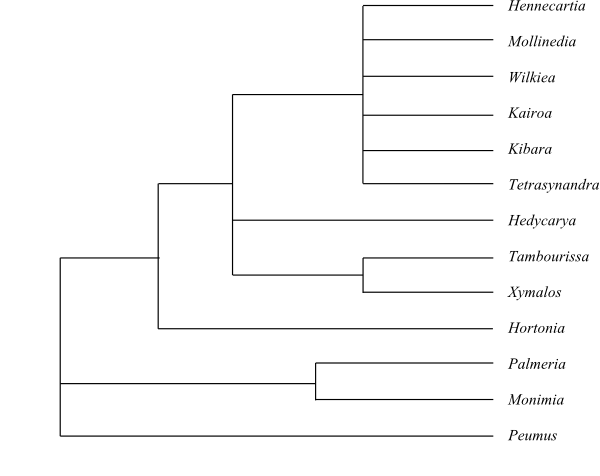

One main clade is identified by Renner (1998) and comprises Hortonia, Hedycarya, Xymalos, Tambourissa, Hennecartia, Kairoa, Kibara, Mollinedia, Tetrasynandra, and Wilkiea (with Hortonia sister to the rest), whereas Peumus, Monimia and Palmeria are basal.

|

Cladogram of Monimiaceae based on DNA sequence data (Renner 1998). |

SIPARUNACEAE (A. DC.) Schodde |

( Back to Laurales ) |

Genera/species 2/c 75

Distribution Central Africa, southern Mexico to tropical South America.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Monoecious or (secondarily) dioecious, evergreen trees or shrubs (sometimes lianas). Often aromatic.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio superficial. Primary stem? Vessel elements with scalariform and/or simple (sometimes reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, simple pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements libriform fibres (fibre tracheids absent?) with simple or bordered pits, non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse, diffuse-in-aggregates, or banded. Sieve tube plastids Psc type, with protein crystalloid and few starch grains. Nodes 1:1–2, unilacunar with one or two leaf traces. Pericycle without hippocrepomorphic sclereids. Crystals acicular?

Trichomes Hairs often stellate or fasciculate (sometimes peltate-lepidote), or absent.

Leaves Opposite, simple, entire, with curved to conduplicate ptyxis; in Glossocalyx anisophylly (one leaf in each leaf pair reduced to tendril-like mid-rib). Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection flattened annular. Venation pinnate, brochidodromous. Stomata paracytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Lamina usually gland-dotted. Medullary plate may occur. Mesophyll with idioblasts containing ethereal oils. Mucilage cells absent. Leaf margin entire or serrate, with monimioid teeth.

Inflorescence Usually axillary (rarely terminal), panicle or spicate. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) two, small, persistent.

Flowers Actinomorphic or zygomorphic. Receptacle expanded into a globose or urceolate hypanthium, surrounding floral parts. Half epigyny. Tepals four to six (to eight), or indistinct (in Glossocalyx), calyptrate, sepaloid, with valvate aestivation, spiral or almost whorled, usually more or less connate, basally forming an annular or flask-shaped inner disc (velum) around androecium and gynoecium, respectively, inside and enclosing hypanthial ostiole. Nectary? Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens two to more than 100 (e.g. 2+2+2; rarely one), spiral. Filaments free from each other and from tepals. Paired nectariferous glands absent. Anthers basifixed to subbasifixed, non-versatile, disporangiate (Siparuna) or tetrasporangiate (Glossocalyx), introrse, dehiscing by longitudinal apically hinged valves (with a single slit). Tapetum secretory. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains inaperturate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with intermediary infratectum, verrucate to echinate or finely spinulate.

Gynoecium Carpels three to more than 100, free or connate at base, embedded in hypanthial wall and disc; carpel plicate and ascidiate (intermediary), partially postgenitally fused, with secretory canal; extragynoecial compitum present. Ovary semi-inferior, unilocular or multilocular. Style single, simple, protruding through ostiole. Stigma capitate, papillate, Dry type? Hyperstigma absent. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation basal. Ovule one per carpel, anatropous, ascending, with micropyle directed downwards, unitegmic (Siparuna) or bitegmic (Glossocalyx), crassinucellar. Micropyle ?-stomal. Outer integument ? cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Ovule pachychalazal. Ovule apex sometimes exposed. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type; megagametophytes in Siparuna several, starchy, uninucleate. Endosperm development ab initio cellular. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A pseudofruit consisting of an assemblage of drupelets surrounded by fleshy hypanthium. Pseudofruit at maturity dehiscing and liberating drupelets. Styles forming a fleshy, arilloid structure, often with different colour and ocurring in dioecious species only.

Seeds Seeds in Glossostigma bilaterally flattened. Aril absent. Seed coat? Exotesta? Mesotesta unspecialized, crushed. Endotesta tracheidal? Tegmen crushed? Endotegmic cells with reticulate thickenings. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, not oily. Embryo very small?, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 22, 44

DNA Duplication of PI?

Phytochemistry Virtually unknown. Isorhamnetin? Benzylisoquinoline alkaloids? Aluminium accumulated.

Use Medicinal plants.

Systematics Siparuna (c 75; southern Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America), Glossocalyx (1; G. longicuspis; tropical West and Central Africa).

Siparunaceae are sister to the clade [Atherospermataceae+Gomortegaceae]. The distribution is tropical amphiatlantic: Siparuna in Central and tropical South America, and Glossocalyx longicuspis in tropical West Africa (Gabon and Cameroon).

Literature

Ablett EM, Playford J, Mills S. 1997. The use of rubisco DNA sequences to examine the systematic position of Hernandia albiflora (C. T. White) Kubitzki (Hernandiaceae), and relationships among the Laurales. – Austrobaileya 4: 601-607.

Adinarayana D, Gunsekar D. 1979. A new flavone from Actinodaphne madraspatana. – Indian J. Chem. 18B: 552.

Alleluia IB de, Braz F R, Gottlieb OR, Magalhães EG, Marques R. 1978. (-)-Rubranine from Aniba rosaeodora. – Phytochemistry 17: 517-521.

Allen CK. 1942. Studies in Lauraceae IV. Preliminary study of the Papuasian species collected by the Archbold expeditions. – J. Arnold Arbor. 23: 112-155.

Allen CK. 1945. Studies in Lauraceae VI. Preliminary survey of the Mexican and Central American species. – J. Arnold Arbor. 26: 280-434.

Allen CK. 1966. Notes on Lauraceae of tropical America I. The generic status of Nectandra, Ocotea, and Pleurothyrium. – Phytologia 13: 221-231.

Alvarez López E. 1955. Comentario sibre “Laurus”, de Ruiz y Pavón, con notas de Dombey acerca de algunas de sus especies. – An. Inst. Bot. Cavanilles 13: 71-78.

Alves FM, Souza VC. 2013. Phylogenetic analysis of the Neotropical genus Mezilaurus and reestablishment of Clinostemon (Lauraceae). – Taxon 62: 281-290.

Bakker ME, Gerritsen AF, Schaaf PJ van der. 1991. Development of oil and mucilage cells in Cinnamomum burmanni: an ultrastructural study. – Acta Bot. Neerl. 40: 339-356.

Balthazar M von, Pedersen KR, Crane PR, Stampanoni M, Friis EM. 2007. Potomacanthus lobatus gen. et sp. nov., a new flower of probable Lauraceae from the Early Cretaceous (Early to Middle Albian) of eastern North America. – Amer. J. Bot. 94: 2041-2053.

Balthazar M von, Crane PR, Pedersen KR, Friis EM. 2011. New flowers of Laurales from the Early Cretaceous (Early to Middle Albian) of eastern North America. – In: Wanntorp L, Ronse DeCraene LP (eds), Flowers on the Tree of Life, Systematic Association Special Volume Series, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 49-87.

Bambacioni-Mezzetti V. 1941. Ricerche morfologiche sulle Lauracee, embriologia della Umbellularia californica Nutt. e del Laurus canariensis Webb. – Ann. Bot. (Roma) 22: 99-119.

Bandulska H. 1926. On the cuticles of some fossil and recent Lauraceae. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 47: 383-425.

Bannister JM, Lee DE, Conran JG. 2012. Lauraceae from rainforest surrounding an early Miocene maar lake, Otago, southern New Zealand. – Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 178: 13-34.

Baruah A, Nath SC. 2007. Cinnamomum champokianum sp. nov. (Lauraceae) from Assam, northeastern India. – Nord. J. Bot. 25: 281-285.

Behnke H-D. 1988. Sieve-element plastids, phloem protein, and evolution of flowering plants III. Magnoliidae. – Taxon 37: 699-732.

Bello MA, González F, Romero de Pérez G. 2002. Morfología del androeceo, tapete y ultrastructura del pollen de Siparuna aspera (Ruiz & Pavón) A. DC. (Siparunaceae). – Rev. Acad. Colomb. Ci. 26(99): 155-167.

Bernardi L. 1962. Lauráceas. – Talleres Gráficos Universitarios, Universidad de Los Andes, Mérida.

Blake ST. 1972. Idiospermum (Idiospermaceae), a new genus and family for Calycanthus australiensis. – Contr. Queensland Herb. 12: 1-37.

Boyle EM. 1980. Vascular anatomy of the flower, seed, and fruit of Lindera benzoin. – Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 107: 409-417.

Brizicky GK. 1959. Variability in the floral parts of Gomortega (Gomortegaceae). – Willdenowia 2: 200-207.

Brophy JJ, Goldsack RJ. 1992. The leaf essential oil of Idiospermum australiense (Diels) S. T. Blake (Idiospermaceae). – Flavour Fragrance J. 7: 79-80.

Brophy JJ, Buchanan AM, Copeland LM, Dimitriadis E, Goldsack RJ, Hibbert DB. 2009. Differentiation between the two subspecies of Atherosperma moschatum Labill. (Atherospermataceae) from their leaf oils. – Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 37: 479-483.

Burger WC. 1988. A new genus of Lauraceae from Costa Rica, with comments on problems of generic and specific delimitation within the family. – Brittonia 40: 275-282.

Buzgó M, Chanderbali AS, Kim S, Zheng Z, Oppenheimer DG, Soltis PS, Soltis DE. 2007. Floral developmental morphology of Persea americana (avocado, Lauraceae): The oddities of male organ identity. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 168: 261-284.

Capuron R. 1966. Hazomalania R. Capuron, nouveaeu genre malgache de la famille des Hernandiacées. – Adansonia, sér. II, 6: 375-376.

Carlquist SJ. 1983. Wood anatomy of Calycanthaceae: ecological and systematic implications. – Aliso 10: 427-441.

Carpenter RJ, Jordan GJ, Hill RS. 2007. A toothed Lauraceae leaf from the early Eocene of Tasmania, Australia. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 168: 1191-1198.

Carpenter RJ, Truswell EM, Harris WK. 2010. Lauraceae fossils from a volcanic Palaeocene oceanic island, Ninetyeast Ridge, Indian Ocean: ancient long-distance dispersal? – J. Biogeogr. 37: 1202-1213.

Chanderbali AS. 2004. Flora Neotropica monograph 91. Endlicheria (Lauraceae). – New York Botanical Garden Press, Bronx, New York.

Chanderbali AS, Werff H van der, Renner SS. 2001. Phylogeny and historical biogeography of Lauraceae: evidence from the chloroplast and nuclear genomes. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 88: 104-134.

Chanderbali AS, Werff H van der, Renner SS, Zheng Z, Oppenheimer DG, Soltis DE, Soltis PS. 2006. Genetic footprints of stamen ancestor guide perianth evolution in Persea (Lauraceae). – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 167: 1075-1089.

Chanderbali AS, Werff H van der, Renner SS. 2001. Phylogeny and historical biogeography of Lauraceae: evidence from the chloroplast and nuclear genomes. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 88: 104-134.

Chang R-H, Ding C-S. 1980. The seedling characters of Chinese Calycanthaceae with a new species of Chimonanthus Lindl. – Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 18: 328-332. [In Chinese with English summary]

Cheadle CL, Esau K. 1958. Secondary phloem of Calycanthaceae. – Univ. Calif. Publ. Bot. 29: 397-510.

Cheng C-H, Chen Y-H, Liu J-W. 2009. Classifying Cinnamomum using rough sets classifier based on interval-discretization. – Plant Syst. Evol. 280: 89-97.

Cheng W-C, Chang S-Y. 1964. Genus novum calycanthaceaearum chinae orientalis. – Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 9: 135-138.

Christophel DC, Rowett AI. 1996. Leaf and cuticle atlas of Australian leafy Lauraceae. – Australian Biological Resources Study, Canberra.

Christophel DC, Kerrigan R, Rowett AI. 1996. The use of cuticular features in the taxonomy of the Lauraceae. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 83: 419-432.

Collins RPN, Chang N, Knaak LE. 1969. Anthocyanins in Calycanthus floridus. – Amer. Midl. Natur. 82: 633-637.

Crepet WL, Nixon KC. 1998. Two new fossil flowers of magnoliid affinity from the Late Cretaceous of New Jersey. – Amer. J. Bot. 85: 1273-1288.

Crepet WL, Friis EM, Gandolfo MA. 2005. An extinct calycanthoid taxon, Jerseyanthus calycanthoides, from the Late Cretaceous of New Jersey. – Amer. J. Bot. 92: 1475-1485.

Crepet WL, Nixon KC, Grimaldi D, Riccio M. 2016. A mosaic Lauralean flower from the Early Cretaceous of Myanmar. – Amer. J. Bot. 103: 290-297.

Datta K, Chanda S. 1980. Pollen morphology of a few members of the order Laurales (sensu Takhtajan) with reference to taxonomy and phylogeny. – Trans. Bose Res. Inst. Calcutta 43: 73-79.

Dengler NG. 1972. Ontogeny of the vegetative and floral apex of Calycanthus occidentalis. – Can. J. Bot. 50: 1349-1356.

Dettmann ME, Clifford HT, Peters M. 2009. Lovellea wintonensis gen. et sp. nov. – Early Cretaceous (late Albian), anatomically preserved, angiospermous flowers and fruits from the Winton Formation, western Queensland, Australia. – Cretaceous Res. 30: 339-355.

Doweld AB. 2001. Carpology and phermatology of Gomortega (Gomortegaceae): systematic and evolutionary implications. – Acta Bot. Malacitana 26: 19-37.

Drinnan AN, Crane PR, Friis EM, Pedersen KR. 1990. Lauraceous flowers from the Potomac group (Mid-Cretaceous) of eastern North America. – Bot. Gaz. 151: 370-384.

Duke RK, Allan RD, Johnston GAR, Mewett KN, Mitrovic AD. 1995. Idiospermuline, a trimeric pyrrolidinoindoline alkaloid from the seed of Idiospermum australense. – J. Nat. Prod. 58: 1200-1208.

Duyfjes BEE. 1996. Hernandiaceae. – In: Kalkman C et al. (eds), Flora Malesiana I, 12(2), Flora Malesiana Foundation, Rijksberbarium/Hortus Botanicus, Leiden, pp. 737-761.

Eklund H. 1999. Big survivors with small flowers. Fossil history and evolution of Laurales and Chloranthaceae. – Acta Univ. Upsal., Uppsala.

Eklund H. 2000. Lauraceous flowers from the Late Cretaceous of North Carolina, U.S.A. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 132: 397-428.

Eklund H, Kvaček J. 1998. Lauraceous inflorescences and flowers from the Cenomanian of Bohemia (Czech Republic, Central Europe). – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 159: 668-686.

Endress PK. 1972. Zur vergleichenden Entwicklungsmorphologie, Embryologie und Systematik bei Laurales. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 92: 331-428.

Endress PK. 1979. Noncarpellary pollination and ‘hyperstigma’ in an angiosperm (Tambourissa religiosa, Monimiaceae). – Experientia 35: 45.

Endress PK. 1980a. Floral structure and relationships of Hortonia (Monimiaceae). – Plant Syst. Evol. 133: 199-221.

Endress PK. 1980b. Ontogeny, function, and evolution of extreme floral construction in Monimiaceae. – Plant Syst. Evol. 134: 79-120.

Endress PK. 1983. Dispersal and distribution in some small archaic relic angiosperm families (Austrobaileyaceae, Eupomatiaceae, Himantandraceae, Idiospermoideae-Calycanthaceae). – Sonderb. Naturwiss. Ver. Hamburg 7: 201-217.

Endress PK. 1992. Protogynous flowers in Monimiaceae. – Plant Syst. Evol. 181: 227-232.

Endress PK, Igersheim A. 1997. Gynoecium diversity and systematics of the Laurales. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 125: 93-168.

Endress PK, Lorence DH. 1983. Diversity and evolutionary trends in the floral structure of Tambourissa (Monimiaeae). – Plant Syst. Evol. 143: 53-81.

Endress PK, Lorence DH. 2004. Heterodichogamy of a novel type in Hernandia (Hernandiaceae) and its structural basis. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 165: 753-763.

Fahn A, Bailey IW. 1957. The nodal anatomy and the primary vascular cylinder of the Calycanthaceae. – J. Arnold Arbor. 38: 107-117.

Feil JP. 1992. Reproductive ecology of dioecious Siparuna (Monimiaceae) in Ecuador – a case of gall midge pollination. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 110: 171-203.

Feil JP, Renner SS. 1991. The pollination of Siparuna (Monimiaceae) by gall-midges (Cecidomyiidae): another likely ancient association. – Amer. J. Bot. 78: 186.

Ferguson DK. 1974. On the taxonomy of recent and fossil species of Laurus (Lauraceae). – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 68: 51-72.

Fernandes JB, Gottlieb OR, Xavier LM. 1978. Chemosystematic implications of flavonoids in Aniba riparia. – Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 86: 55-58.

Ferreira ZS, Gottlieb OR, Roque NF. 1980. Chemosystematic implications of benzyltetrahydroisoquinolines in Aniba. – Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 88: 51-54.

Fijridiyanto IA, Murakami N. 2009. Phylogeny of Litsea and related genera (Laureae-Lauraceae) based on analysis of rpb2 gene sequences. – J. Plant Res. 122: 283-298.

Foreman DB. 1984. The morphology and phylogeny of the Monimiaceae (sensu lato) in Australia. – Ph.D. diss., University of New England, Armidale, Australia.