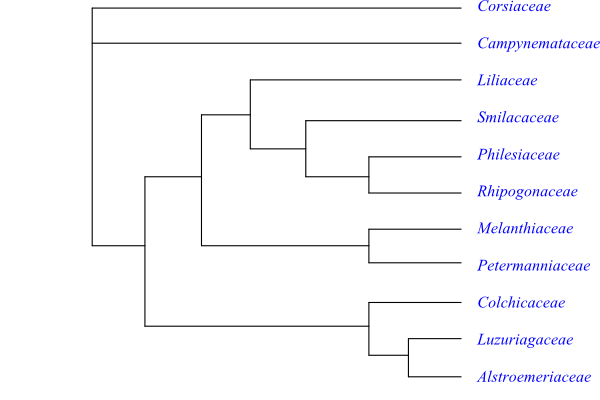

Cladogram of Liliales based on DNA sequence data (Kim & al. 2013; Corsiaceae added). Corsiaceae are sister to Campynemataceae in the analyses by Givnish & al. (2016).

[Liliales+[Iridales+Commelinidae]]

Liriopsida Brongn., Enum. Plant. Mus. Paris: xv, 17. 12 Aug 1843 [’Lirioideae’]

Fossils Monocotylostrobus bracteatus, an inflorescence from the Deccan Intertrappean Beds, has been assigned to Liliaceae, although this assessment may be questioned.

Habit Usually bisexual (sometimes andromonoecious, polygamous, dioecious, androdioecious, or gynodioecious), perennial herbs (sometimes with more or less lignified stem). Usually with a bulb (sometimes a corm, rarely a tuberous rhizome). Sometimes twining or climbing.

Vegetative anatomy Usually Paris type arbuscular mycorrhiza. Bulb with or without tunica. Velamen sometimes present. Phellogen absent. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels present in roots (sometimes also in stem). Vessel elements usually with scalariform (sometimes simple) perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals, without starch or protein filaments. Nodes multilacunar with several leaf traces. Silica bodies absent. Calciumoxalate as raphides or druses (sometimes crystal sand or solitary crystals) present or absent.

Trichomes Hairs usually absent (sometimes unicellular, bicellular or multicellular, uniseriate, simple).

Leaves Alternate (spiral or distichous; sometimes seemingly opposite or verticillate), simple, entire, usually linear (sometimes subulate; sometimes resupinate; rarely differentiated into pseudopetiole and pseudolamina), with convolute, supervolute, conduplicate, curved or flat ptyxis. Stipules absent; leaf sheath usually absent (sometimes well developed, open or closed). Venation usually parallelodromous (sometimes acrodromous or palmatireticulate; rarely reticulate or pinnate-campylodromous). Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids as parallel platelets (Convallaria type, resembling ‘electromagnetic field lines’; sometimes as stalk-like structures). Mesophyll with or without idioblasts containing calciumoxalate raphides (sometimes single prismatic crystals). Tanniniferous cells sometimes present. Leaf margin usually entire (rarely serrate).

Inflorescence Usually terminal (sometimes axillary), paniculate, thyrsoid, botryoid, stachyoid, cincinnus, umbellate, capitate, spicate or raceme-like, or racemose, simple or branched, or flowers solitary terminal. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) lateral or absent.

Flowers Usually actinomorphic (sometimes zygomorphic). Usually hypogyny (sometimes epigyny, rarely half epigyny). Tepals 3(–6)+3(–6) (rarely three, four, seven, twelve or more than twelve), with imbricate or contorted aestivation, usually petaloid (sometimes sepaloid), often spotted or striate, usually free (rarely connate at base). Tepal nectaries (often as nectariferous glands) present at tepal bases (sometimes androecial nectaries; nectary sometimes absent). Septal nectaries absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens usually as many as tepals, in two whorls (rarely only three outer stamens, or up to 24 in several whorls). Filaments free from each other, usually free from tepals (sometimes epitepalous in lower part). Anthers pseudobasifixed (filament apex surrounded by tubular connective), basifixed or dorsifixed, versatile or non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, extrorse, introrse or latrorse, usually longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits, rarely poricidal, dehiscing by apical pores). Tapetum usually secretory (sometimes amoeboid-periplasmodial). Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains usually monosulcate (rarely 2–4-sulcate, 2–4-foraminate, tetraporate, or inaperturate), shed as monads, bicellular or tricellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate (rarely intectate), usually with columellate (rarely granular) infratectum, reticulate, striate or striato-reticulate, foveolate, verrucate-areolate, verrucate, rugulate, clavate, corrugate, echinate, spinulate, gemmate, or psilate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (one to) three (to ten) connate carpels. Ovary usually superior (sometimes inferior, rarely semi-inferior), trilocular (rarely unilocular, bilocular or quadrilocular to decemlocular). Style single, simple or lobate, or stylodia free. Stigma single, capitate or slightly lobate, or stigmas several, punctate, papillate (with unicellular papillae), usually Dry (sometimes Wet) type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation usually axile (rarely parietal or subparietal). Ovules one to more than 100 per carpel, usually anatropous (sometimes campylotropous, rarely hemianatropous, orthotropous or amphitropous), ascending to pendulous, apotropous?, epitropous, plagiotropous, basitropous, pleurotropous, or hypotropous, usually bitegmic (rarely unitegmic), usually tenuinucellar (sometimes crassinucellar). Micropyle usually endostomal (sometimes bistomal). Funicular obturator often present. Parietal cell not formed, or formed from archesporial cell. Periclinal cell divisions sometimes occurring at single-layered megasporangial apex. Nucellar cap sometimes present. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type, or tetrasporous, Fritillaria type (rarely Clintonia type, 8-nucleate, Adoxa type, or 16-nucleate, Drusa type, or disporous, Allium type, Veratrum lobelianum type or Scilla type). Synergids sometimes with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells persistent, sometimes proliferating. Endosperm development usually nuclear (sometimes helobial). Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis onagrad, asterad or chenopodiad.

Fruit Usually a loculicidal capsule (sometimes septicidal, ventricidal or irregularly dehiscent; occasionally a berry or berry-like).

Seeds Aril absent (strophiole or caruncle sometimes present). Elaiosome (from raphe and chalaza, or from raphe and hilum) sometimes present. Testa thin (often with two cell layers), with cells often flat or collapsed (sometimes with lignified walls; exotestal epidermis sometimes with phlobaphene). Sarcotesta rarely present. Exotesta sometimes palisade, sometimes collapsing. Tegmen strongly compressed, thin, often collapsing. Endotegmic cells sometimes with phlobaphene. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, with aleurone and/or oils (starch absent), with thick and pitted cell walls with hemicellulose. Embryo straight, little differentiated to well differentiated, without chlorophyll. Cotyledon one, usually photosynthesizing, bifacial. Cotyledon hyperphyll usually elongate (sometimes compact), usually assimilating. Hypocotyl internode short or absent. Coleoptile absent. Radicula persistent. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology x = 5–14(–19)

DNA Mitochondrial gene sdh3 lost.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), flavones, flavanones, luteolin, apigenin, etc., chalcones, tannins, alkaloids without 7-C-tropolone ring (androcymbine, floramultine, kreysigine, etc.) or with 7-C-tropolone ring (e.g. colchicine), steroidal alkaloids (ceveratrum and jerveratrum alkaloids, veratramine, zigadenine, jervine, etc.), steroidal saponins (e.g. lilagenin, yuccagenin, diosgenin), anthraquinones, tulipalines (butyrolactone), chelidonic acid fructans, glucose esters (tuliposides), and saccharose esters of diferulic or triferulic acid present. Ellagic acid, proanthocyanidins, and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Systematics Liliales are sister-group to the [Iridales+Commelinidae] clade in most molecular analyses.

Corsiaceae, Campynemataceae and the remaining Liliales form a basal trichotomy (Fay & al. 2006). This third clade has relatively high bootstrap support, but no unambiguous morphological synapomorphies can be postulated so far (the fruit is often a berry). A subbasal trichotomy comprises the clades Melanthiaceae, [[Philesiaceae+Rhipogonaceae]+[Smilacaceae+Liliaceae]] and [Petermanniaceae+[Colchicaceae+[Alstroemeriaceae+Luzuriagaceae]]]. Arachnitis (Corsiaceae) and Campynemataceae formed a sister-group to the remaining Liliales and the Melanthiaceae were placed as sister to the PR+SL clade in the analysis by Givnish & al. (2016). In Petersen & al. (2013) Arachnitis was placed as sister-group to the remaining Liliales, whereas Mennes & al. (2015) found the Corsiaceae (Corsia+Arachnitis) to be sister-group to the Campynemataceae. The Philesiaceae-Liliaceae clade is supported by the potential synapomorphies (Stevens 2001 onwards): broad leaves with reticulate venation; relatively small flowers; and a baccate fruit. Philesiaceae and Rhipogonaceae share the synapomorphies: leaves with pseudopetiole, pseudolamina and a midrib; cuticular wax crystalloids as parallel platelets; tepals not spotted; ovules crassinucellar; testa disintegrating; and absence of stem fructans. Smilacaceae and Liliaceae may share the basic chromosome number x=8.

The clade [Petermanniaceae+[Colchicaceae+[Luzuriagaceae+Alstroemeriaceae]]] is characterized by a well developed seedling primary root (Stevens 2001 onwards). Alstroemeriaceae and Luzuriagaceae have the following features in common: resupinate leaves; placentation sometimes parietal; testa and tegmen thin-walled; and a bimodal karyotype.

Colchicaceae, Corsiaceae, Liliaceae, and Melanthiaceae, have tepals with three traces, whereas in Petermannia and Smilacaceae each tepal has a single trace.

|

Cladogram of Liliales based on DNA sequence data (Kim & al. 2013; Corsiaceae added). Corsiaceae are sister to Campynemataceae in the analyses by Givnish & al. (2016). |

ALSTROEMERIACEAE Dumort. |

( Back to Liliales ) |

Alstroemeriales Hutch., Fam. Fl. Pl., Monocot. 2: 12, 111. 20 Jul 1934

Genera/species 2–3/210–240

Distribution Central Mexico and the West Indies southwards to Chile and Argentina, with the largest diversity in the Andes.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, usually perennial (in Alstroemeria rarely annual) herbs. Sometimes climbing. Roots often swollen, fusiform or tuberous, storing water and nutrients.

Vegetative anatomy Roots usually fibrous, without velamen. Phellogen absent. Stem vascular bundles usually present inside a sclerenchymatous cylinder. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels present in roots and stem. Vessel elements usually with scalariform (in roots often also simple) perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals. Nodes? Calciumoxalate raphides present in Alstroemeria.

Trichomes Hairs usually absent (sometimes unicellular, bicellular or multicellular, uniseriate, with a basal cell).

Leaves Alternate (spiral), simple, entire, more or less resupinate (twisted 180° at base), often linear, with conduplicate or supervolute? ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Venation parallelodromous. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids as parallel platelets (Convallaria type). Mesophyll with calciumoxalate raphides. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Usually terminal (sometimes axillary) umbel-like, thyrse, simple or branched, consisting of helicoid cymes (flowers rarely solitary terminal), often subtended by large green foliaceous bracts. Foliar prophylls (bracteoles) lateral.

Flowers Actinomorphic or zygomorphic, often large. Epigyny. Tepals 3+3, petaloid, often dotted to striated, usually caducous, free; in Alstroemeria median tepal of outer whorl adaxial. Inner tepals usually with canaliculate base with tepal nectaries (in Leontochir with nectariferous pocket). Septal nectaries absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens 3+3. Filaments filiform, free from each other and from tepals. Anthers pseudobasifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse to latrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory, with binucleate cells. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains monosulcate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, striate to striato-reticulate (Alstroemeria) or reticulate (Bomarea, Leontochir).

Gynoecium Pistil composed of three connate carpels. Ovary inferior, unilocular (Leontochir, the ’Schickendantzia clade’ of Alstroemeria) or trilocular (Alstroemeria, Bomarea). Style single, simple, filiform. Stigma trilobate, Wet type (at least in Alstroemeria). Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation axile (Alstroemeria, Bomarea) or parietal (Leontochir, the ’Schickendantzia clade’ of Alstroemeria). Ovules c. 20 to more than 100 per carpel, anatropous, bitegmic, tenuinucellar. Micropyle endostomal. Outer integument ? cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Parietal cell not formed (parietal tissue absent). Nucellar cap absent. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit Usually a loculicidal capsule (dry to fleshy, rarely indehiscent; in Alstroemeria usually explosively dehiscent; fruit in some species of Bomarea berry-like).

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat testal. Testa undifferentiated or more or less thick-walled, usually dry. Sarcotesta present in Bomarea and Leontochir. Exotesta? Endotesta? Tegmen collapsing and membranous. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, with oils and aleurone (starch absent), with thick and pitted cell walls. Embryo straight, often short, well differentiated, chlorophyll? Cotyledon one, usually not photosynthesizing (in Alstroemeria graminea, an annual species, photosynthesizing). Cotyledon hyperphyll elongate and assimilating, or compact and not assimilating. Hypocotyl internode short. Coleoptile absent. Radicula persistent. Germination?

Cytology n = 8, 9 – Karyotype bimodal. Chromosomes 6–19 µm long.

DNA Very large genomes (with a C value of c. 350 pg or more) are found in some species.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), steroidal saponins, tannins, anthraquinones, chelidonic acid, and glucose esters (tuliposides) present. Flavones, ellagic acid, proanthocyanidins, alkaloids, and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Ornamental plants, starch sources (Alstroemeria ligtu, Bomarea edulis).

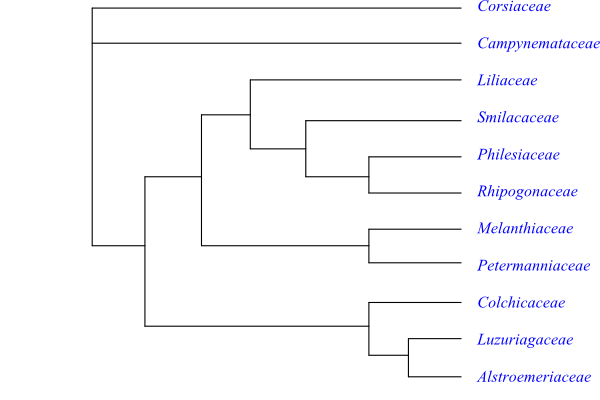

Systematics Leontochir (1; L. ovallei; coast of northern Chile; in Bomarea?), Bomarea (110–120; Mexico, Central America, tropical South America; incl. Leontochir?), Alstroemeria (100–120; western and eastern South America, especially the Andes).

Alstroemeriaceae are sister to Luzuriagaceae.

Based on morphology, Bomarea appears to be paraphyletic, when Leontochir is excluded.

|

Cladogram (simplified) of Alstroemeriaceae based on DNA sequence data (Aagesen & Sanso 2003). |

CAMPYNEMATACEAE Dumort. |

( Back to Liliales ) |

Campynematales Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.: lvi. 23 Dec 2001; Campynematineae Reveal in Kew Bull. 66: 47. Mar 2011

Genera/species 2/4

Distribution New Caledonia,Tasmania.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, perennial herbs.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen absent. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels present in roots (Campynema) or absent (Campynemanthe). Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids probably P2c type. Nodes? Calciumoxalate raphides present in idioblasts.

Trichomes Hairs absent.

Leaves Alternate (spiral), simple, entire, linear, with ? ptyxis. Stipules absent; leaf sheath well developed. Leaf base fibrous, persistent. Venation parallelodromous; reticulate fine venation absent. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Mesophyll with idioblasts containing calciumoxalate raphides. Leaf margin entire (leaf apex in Campynemanthe tridentate).

Inflorescence Terminal, umbel-like (pseudo-umbel) or raceme-like, cymose.

Flowers Actinomorphic. Epigyny (Campynema) or half epigyny (Campynemanthe). Tepals 3+3, sepaloid to petaloid, persistent, free. Tepal nectaries present in Campynemanthe. Septal nectaries absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens 3+3. Filaments free from each other, adnate to tepal bases. Anthers dorsifixed (Campynema) or basifixed (Campynemanthe), usually non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, extrorse (Campynema) or introrse to almost latrorse (Campynemanthe), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory, with binucleate (Campynemanthe) or multinucleate (Campynema) cells. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains monosulcate (Campynema) or inaperturate to indistinctly sulcate (Campynemanthe), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate? infratectum, rugulate (Campynemanthe).

Gynoecium Pistil composed of three connate carpels. Ovary inferior (Campynema) or semi-inferior (Campynemanthe), unilocular (Campynema) or trilocular (Campynemanthe). Style single, simple (Campynemante), or stylodia three free (Campynema). Stigma single, capitate, or stigmas three, punctate, type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation axile (when ovary trilocular) or parietal (when ovary unilocular). Ovules three to more than 50 per carpel, anatropous, bitegmic, weakly crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal. Outer integument two cell layers thick. Inner integument two cell layers thick. Parietal cell (producing parietal tissue) formed from archesporial cell. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A capsule, dehiscing by degradation of lateral or dorsal walls, or indehiscent, with persistent and accrescent perianth.

Seeds Aril absent. Exotestal epidermis with large non-compressed cells. Endotesta? Exotegmen? Endotegmic epidermis with large non-compressed cells; endotegmic cells with (reddish-brown) phlobaphene. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, oily, with hemicellulose in cell walls. Embryo very small, chlorophyll? Cotyledon one. Cotyledon hyperphyll? Hypocotyl internode? Coleoptile? Germination?

Cytology n = 11 – Chromosomes up to 3 µm long.

DNA

Phytochemistry Virtually unknown. Steroidal saponins and sapogenins present.

Use Unknown.

Systematics Campynemanthe (3; C. neocaledonica, C. parva, C. viridiflora; New Caledonia), Campynema (1; C. lineare; Tasmania).

Campynemataceae are sister to the remaining Liliales in the analyses by Kim & al. (2013), although Corsiaceae were not included in their study. Givnish & al. (2016) recovered Corsiaceae as sister-group to Campynemataceae in their phylogenomic study of Liliales.

COLCHICACEAE DC. |

( Back to Liliales ) |

Merenderaceae Mirb., Hist. Nat. Plant. 8: 211. 1804 [‘Merenderae’]; Colchicales Dumort., Anal. Fam. Plant.: 59. 1829 [‘Colchicarieae’]; Methonicaceae E. Mey., Preuss. Pfl.-Gatt.: 43. 1839 [‘Menthoniceae’], nom. illeg.; Uvulariaceae A. Gray ex Kunth, Enum. Plant. 4: 199. 17-19 Jul 1843 [‘Uvularieae’], nom. cons.; Bulbocodiaceae Salisb., Gen. Plant.: 52. 15-31 Mai 1866 [‘Bulbocodeae’]; Burchardiaceae Takht. in Bot. Žurn. 81(2): 85. Mai-Jun 1996

Genera/species 15/275–280

Distribution Europe, Africa, Southwest, East and Southeast Asia to New Guinea, Australia and New Zealand, North America, with their largest diversity in South Africa and Australia.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Usually bisexual (in Wurmbea rarely dioecious), perennial herbs. Usually with a starch-rich corm (with basal innovation; in Gloriosa a hypopodial tuber; corm in Gloriosa and Sandersonia stoloniferous). Stem usually herbaceous (in Kuntheria more or less lignified), in Gloriosa twining with apical foliar tendrils, in Gloriosa, Uvularia etc. branched.

Vegetative anatomy Roots usually fibrous (in Burchardia tuberous). Phellogen absent. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels present in fibrous roots (in some genera also in stem). Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals. Nodes? Laticifers absent. Silica bodies absent. Calciumoxalate raphides usually absent. Crystal sand present in some species.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate, or absent.

Leaves Alternate (distichous) or (pseudo?)verticillate, simple, entire, often linear (sometimes subulate), sometimes differentiated into pseudopetiole and pseudolamina, with conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules absent; leaf sheath often well developed. Venation parallelodromous, often with distinct mid-vein (sometimes with reticulate fine venation). Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids as parallel platelets (Convallaria type). Mesophyll with calciumoxalate as crystal sand. Leaf margin entire. Leaf apex in Gloriosa often transformed into a tendril.

Inflorescence Axillary, usually umbel-, head-, spike- or raceme-like (flowers sometimes solitary).

Flowers Actinomorphic or somewhat zygomorphic, often large. Hypogyny. Tepals usually 3+3 (rarely seven to twelve), at base U-shaped in bud and folded around each stamen, petaloid, sometimes clawed (rarely with basal spur), persistent or caducous, free or more or less connate at base (in, e.g., Colchicum and Wurmbea connivent into a tube). Nectaries present at tepal bases (tepal nectaries) and/or stamens (androecial nectaries in Colchicum), or absent. Septal nectaries absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens 3+3. Filaments subulate or flattened in transverse section (sometimes with basal appendages), usually free (sometimes connate), free from or adnate to tepals. Anthers dorsifixed or basifixed, sometimes versatile, tetrasporangiate, usually extrorse (sometimes latrorse, rarely introrse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains usually monosulcate (sometimes 2–4-sulcate or 2–4-foraminate), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, usually reticulate or microreticulate (rarely foveolate-spinulate). Pollen grains sometimes operculate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (two or) three (or four) connate carpels. Ovary superior, usually trilocular (rarely bilocular or quadrilocular). Style single, simple (Camptorrhiza) or trilobate, or stylodia three, free. Stigma capitate or trilobate, with reflexed lobes, Dry or Wet type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation axile. Ovules two to more than 50 per carpel, anatropous to campylotropous, usually ascending, epitropous, plagiotropous or basitropous, usually bitegmic (rarely unitegmic), (pseudo)crassinucellar. Micropyle bistomal. Outer integument ? cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Nucellar cap sometimes present. Parietal cell not formed (parietal tissue absent). Periclinal cell divisions often taking place in megasporangial epidermis (e.g. Colchicum, Gloriosa, Iphigenia; not in Uvularia). Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Antipodal cells multinucleate, sometimes proliferating (at least in Iphigenia). Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis onagrad or asterad. Nucellar (megasporangial) embryony occurring in Colchicum.

Fruit Usually a septicidal and/or loculicidal capsule (in Disporum a berry).

Seeds Strophiole, caruncle or aril present (in, e.g., Uvularia) or absent. Seed coat testal. Unripe testa starchy. Exotestal epidermis often with phlobaphene, a reddish-brown pigment; exotestal cell walls usually thick (in Colchicum narrower). Tegmen more or less collapsing, often pigmented. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, with oils and aleurone (rarely starch), usually with thick and pitted cell walls. Embryo usually small, straight, chlorophyll? Cotyledon one, usually bifacial (sometimes ligulate), coleoptile-like, often photosynthesizing. Cotyledon hyperphyll compact, not assimilating. Hypocotyl internode and mesocotyl absent. Radicula ephemeral or persistent. Germination?

Cytology x = 5–12(–19) – Polyploidy and aneuploidy occurring. Chromosomes 1–16 µm long.

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols, tannins, alkaloids without a 7-C-tropolone ring (androcymbine, floramultine, kreysigine, etc.) or with a 7-C-tropolone ring (colchicines etc.), anthraquinones, and chelidonic acid present. Flavones and tricine (flavone-3’,5’-dimethyl ether of tricetin) rare. Ellagic acid, proanthocyanidins, steroidal saponins, and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Ornamental plants, medicinal plants (Colchicum, Gloriosa etc.), plant breeding (Colchicum autumnale).

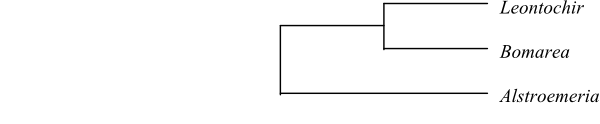

Systematics Colchicaceae are sister to the clade [Luzuriagaceae+Alstroemeriaceae].

[Uvularieae+[Burchardieae+[Tripladenieae+[Colchiceae+[Iphigenieae+Anguillarieae]]]]]

Uvularieae are sister-group to remaining Colchicaceae (Kim & al. 2013; Thi Nguyen & al. 2013). Uvularieae and Tripladenieae are rhizomatous herbs possessing enlarged cells in the megasporangial epidermis. They have flavonols, but seem to lack alkaloids.

Uvularieae A. Gray ex Meisn., Plant. Vasc. Gen.: Tab. Diagn. 397, 402, Comm. 306. 17-20 Aug 1842

2/c 25. Uvularia (5; U. floridana, U. grandiflora, U. perfoliata, U. puberula, U. sessilifolia; southeastern Canada, eastern United States), Disporum (c 20; northern India, East and Southeast Asia to Japan and West Malesia). – Northern India, East and Southeast Asia, West Malesia, eastern North America. Uvularieae are rhizomatous herbs with distichous leaves, often with disulcate pollen grains. Nucellar cap is not formed. n = 7 (Uvularia) or 8, 15, 16 (Disporum). – Chacón & al. (2014) recovered Uvularia as sister to the remaining Colchicaceae except Burchardia.

[Burchardieae+[Tripladenieae+[Colchiceae+[Iphigenieae+Anguillarieae]]]]

Burchardieae (Benth.) J. C. Manning et Vinn. in Taxon 56: 177. 12 Mar 2007

1/6. Burchardia (6; B. bairdiae, B. congesta, B. monantha, B. multiflora, B. rosea: southwestern Western Australia; B. umbellata: southeasternmost Queensland, eastern New South Wales, South Australia, Victoria, Tasmania; paraphyletic). – The vertical rhizome in Burchardia is short and wears papery scales, the leaf base is sheathing, styluli are present, and the capsule is septicidal (Stevens 2001 onwards). n = 24, 48. – Burchardia is possibly sister-group to the remaining Colchicaceae with axillary flowers (Thi Nguyen & al. 2013). On the other hand, Burchardia formed a basal grade in the analysis by Vinnersten & Manning (2007) and was sister to all other Colchicaceae in Chacón & al. (2014).

[Tripladenieae+[Colchiceae+[Iphigenieae+Anguillarieae]]]

Tripladenieae Vinn. et J. C. Manning in Taxon 56: 177. 12 Mar 2007

3/4. Tripladenia (1; T. cunninghamii; southeasternmost Queensland, northeastern New South Wales), Schelhammera (2; S. multiflora: East Malesia, New Guinea, northeastern Queensland; S. undulata: eastern New South Wales, Victoria), Kuntheria (1; K. pedunculata; northeastern Queensland). – East Malesia, New Guinea, southwestern and eastern Australia. Rhizomatous herbs with distichous leaves. n = 7, 18.

[Colchiceae+[Iphigenieae+Anguillarieae]]

Stevens (2001 onwards) lists the following synapomorphies of this clade: corm with tunica; sheathing leaf base; nectaries usually present on filament bases; and presence of alkaloids with a 7-C-tropolone ring.

Colchiceae T. Nees et C. H. Eberm. ex Endl., Gen. Plant.: 137. Dec 1836

5/c 180. Colchicum (c 160; the Canary Islands, the Mediterranean to Ethiopia, Somalia and southern Africa, Central Asia, northern India), Hexacyrtis (1; H. dickiana; Namibia), Ornithoglossum (8; tropical and southern Africa), Sandersonia (1; S. aurantiaca; South Africa, Swaziland), Gloriosa (c 12; tropical and southern Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, tropical Asia to Malesia). – Europe, Africa, Central Asia to Malesia. Usually with nectaries median on tepals or staminal bases. The antipodal cells are often proliferating. n = 9–11, 18–21, 27 (Colchicum), 11 (Hexacyrtis), 11, 22, 33 (Gloriosa), or 12 (Ornithoglossum, Sandersonia). – Sandersonia has vessels in the stem.

[Iphigenieae+Anguillarieae]

Iphigenieae Hutch., Fam. Fl. Plants 2: 84, 101. 20 Jul 1934

2/12–13. Iphigenia (11–12; tropical and southern Africa, Madagascar, Socotra, India, Australia, New Zealand), Camptorrhiza (1; C. strumosa; southern Africa to Zimbabwe and Mozambique). – Old World tropical regions, South Africa. Nectaries absent. n = 11. – The antipodal cells in Iphigenia are persistent. Iphigenia novae-zelandiae in New Zealand should perhaps be transferred to Wurmbea (Anguillarieae).

Anguillarieae (D. Don) Pfeiff., Nomencl. Bot. 1(1): 192. ante 10 Mai 1872

2/35–40. Baeometra (1; B.

uniflora; Western Cape), Wurmbea

(c 40; South Africa, Swaziland, Australia). n = 7, 10, 20 (Wurmbea)

or 11 (Baeometra). – Southern Africa, Australia (possibly New

Zealand). Inflorescence is an ebracteate raceme or spike.

|

Cladogram (simplified) of Colchicaceae based on DNA sequence data (Kim & al. 2013; Thi Nguyen 2013). |

CORSIACEAE Becc. |

( Back to Liliales ) |

Genera/species 1/c 25

Distribution Southern China, New Guinea, Solomon Islands, northern Queensland (Australia), Bolivia, central and southern Chile, the Falkland Islands.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual (extremely protandrous), perennial herbs. Achlorophyllous mycoheterotrophic holoparasites.

Vegetative anatomy Arbuscular mycorrhiza (Glomeraceae). Roots long, widely branched. Phellogen absent. Collateral or concentric stem vascular bundles forming a cylinder, each bundle often surrounded by sclerenchymatous layers. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels absent. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids probably P2c type. Silica bodies absent. Raphides absent.

Trichomes Hairs absent.

Leaves Alternate (spiral or distichous), simple, entire, scale-like. Stipules absent; leaf sheath closed. Venation parallelodromous. Stomata absent? Cuticular wax crystalloids in Corsia as parallel platelets (Convallaria type), in Arachnitis tubuli, chemically dominated by nonacosan-10-ol. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Flowers solitary terminal, without bracts.

Flowers Zygomorphic, usually resupinate. Epigyny. Tepals 3+3, petaloid, persistent?, free; median outer tepal, ’labellum’, strongly enlarged, with a ’callus’ at base consisting of thicker tissue and with outgrowths of various shape (nectariferous in some species). Tepal nectaries sometimes present on median outer tepal. Septal nectaries absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens in Corsia 3+3, in Arachnitis 3 antepetalous. Filaments free from each other and from tepals, in Corsia adnate at base to style into a gynostemium. Anthers dorsifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, extrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum? Antesepalous staminodium present adjacent to ‘labellum’.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains monoporate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine semitectate, with columellate? infratectum, reticulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of three connate carpels. Ovary inferior, unilocular. Style in Corsia single; in Arachnitis stylodia three, free. Stigma trilobate, papillate, type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation intrusively parietal. Ovules c. 25 to more than 100 per ovary, anatropous, pendulous, bitegmic, crassinucellar (tenuinucellar?). Micropyle ?-stomal. Outer integument two cell layers thick. Inner integument two cell layers thick. Funicle long. Parietal tissue one cell layer thick. Nucellar cap? Sometimes two cell layers present above megasporocyte. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development helobial. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A loculicidal? capsule, in Arachnitis circumscissilely dehiscent.

Seeds Aril absent. Seeds extremely small, winged. Seed coat testal. Exotestal epidermis with prosenchymatous, elongate cells with convex periclinal walls (in Arachnitis with collapsing membranous outer periclinal cell walls). Endotesta? Tegmen collapsed? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm small, multicellular, proteinaceous and often oily, with hemicellulose in cell walls. Embryo c. 50-cellular (in Arachnitis tricellular), undifferentiated, chlorophyll? Suspensor short. Cotyledon one. Germination phanerocotylar?

Cytology n = 9

DNA

Phytochemistry Unknown.

Use Unknown.

Systematics Corsia (c 25), Arachnitis (1; A. uniflora; Bolivia, central and southern Chile, the Falkland Islands).

Davis & al. (2004) suggested that Corsiaceae should be included in Liliales. This position has relatively weak support, yet largely corresponds with morphological features and their opinion is followed here (see Mennes & al. 2015, Givnish & al. 2016).

Arachnitis is sister to Thismia, according to some 26SrDNA sequence analyses (Neyland & Hennigan 2003). Like several Thismiaceae Arachnitis has a tuber with a single shoot, whereas Corsia has a rhizome with several shoots. In a study of familial relationships in the Liliales, Kim & al. (2013) added Arachnitis to the analyses and did not find any close affinity between A. uniflora and the investigated taxa of Liliales. Unfortunately, they did not analyse any member of Corsia and used only one locus for the phylogenetic analysis. According to Mennes & al. (2015), the placement of Arachnitis outside of Liliales was probably the result of DNA contamination. However, Givnish & al. (2016) using 75 plastid genes found Arachnitis to be sister to Corsia, although having an extremely long branch-length. Like Corsia but unlike Thismiaceae, Arachnitis has hemicellulose in the cell walls of the endosperm. On the other hand, Arachnitis differs from Corsia in, e.g., having tubular cuticular wax crystalloids, three antepetalous stamens, three free stylodia, capsule with a terminal opening instead of three lateral valves, seeds similar to those in Orchidaceae, and embryo tricellular instead of multicellular.

LILIACEAE Juss. |

( Back to Liliales ) |

Liriaceae Batsch ex Borkh., Bot. Wörterb. 1: 374. 1797 [‘Liria’]; Tulipaceae Batsch ex Borkh., Bot. Wörterb. 2: 391. 1797; Erythroniaceae Martinov, Tekhno-Bot. Slovar: 238. 3 Aug 1820 [‘Erythronides’]; Calochortaceae Dumort., Anal. Fam. Plant.: 53. 1829 [‘Calocorthineae’]; Compsoaceae Horan., Prim. Lin. Syst. Nat.: 51. 2 Nov 1834 [‘Hypoxideae s. Compsoaceae’]; Liriales K. Koch, Nat. Syst. Pflanzenr.: 151. 3-9 Nov 1839 [‘Liranthae’]; Fritillariaceae Salisb., Gen. Plant.: 56. 15-31 Mai 1866 [‘Fritillareae’]; Medeolaceae (S. Watson) Takht., Sist. Magnoliof. [Systema Magnoliophytorum]: 291. 24 Jun 1987; Scoliopaceae Takht. in Bot. Žurn. 81(2): 86. Mai-Jun 1996; Tricyrtidaceae Takht., Divers. Classif. Fl. Pl.: 482. 24 Apr 1997, nom. cons.

Genera/species 16/575–>600

Distribution Temperate and subtropical regions on the Northern Hemisphere, Central America, with their highest diversity in West and East Asia and the Himalayas.

Fossils Uncertain.

Habit Bisexual, perennial herbs. Usually with a bulb (in Medeola a tuberous rhizome). Axillary bulbils sometimes present (in, e.g., some species of Lilium).

Vegetative anatomy Roots often contractile, with or without velamen. Root hypodermis dimorphic. Bulb with or without tunica. Phellogen absent. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels present at least in roots (in Tricyrtis also in stem). Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals. Nodes? Calciumoxalate raphides absent.

Trichomes Hairs usually absent (sometimes unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate).

Leaves Alternate (usually spiral; sometimes seemingly opposite or verticillate), simple, entire, usually linear (sometimes subulate), with convolute to curved or flat ptyxis. Stipules absent; leaf sheath usually absent. Venation usually parallelodromous (rarely reticulate). Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids as non-orientated tubuli or granules, chemically dominated by nonacosan-10-ol (in Tricyrtis absent). Mesophyll with or without calciumoxalate crystals. Leaf margin entire. Extrafloral nectaries sometimes present.

Inflorescence Usually terminal (in Streptopus axillary?), thyrsoid, umbel-like or racemose, or flowers solitary. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) lateral or absent.

Flowers Usually actinomorphic (in some species of Fritillaria slightly zygomorphic), often large. Hypogyny. Tepals 3+3, usually all petaloid (inner tepals rarely, e.g. in Nomocharis, fimbriate or pubescent), often spotted or striated, free. Tepal nectaries (often as nectariferous glands) present at tepal bases. Septal nectaries absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens usually 3+3 (in Scoliopus only three outer stamens). Filaments often filiform, sometimes flattened (rarely swollen with needle-like apex), free, in Calochortus and Streptopeae adnate in lower part to tepals. Anthers pseudobasifixed (filament apex surrounded by tubular connective), basifixed or dorsifixed, often versatile, tetrasporangiate, extrorse, latrorse or introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory, with binucleate or multinucleate cells. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains usually monosulcate (rarely disulcate, trisulcate or inaperturate; in Tulipa sometimes operculate), shed as monads, bicellular or tricellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, reticulate, verrucate-areolate, gemmate or rugulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of three connate carpels. Ovary superior, usually trilocular (rarely unilocular or bilocular). Style single, long, short or rudimentary, or trifid at apex. Stigma capitate or trilobate, papillate (with unicellular papillae), usually Dry (sometimes Wet) type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation usually axile (in Medeola, Calochortus, and Scoliopus parietal). Ovules two to more than 50 per carpel, anatropous, pendulous, pleurotropous, hypotropous or epitropous, bitegmic, tenuinucellar. Micropyle endostomal. Outer integument with two to more than three (to six) cell layers thick. Inner integument two? cell layers thick. Funicular obturator sometimes present. Megasporangial apex one-layered, usually without periclinal cell divisions (occurring in Calochortus and Streptopeae). Nucellar cap usually one to three cell layers thick (sometimes absent?). Parietal cell not formed (parietal tissue absent). Megagametophyte usually tetrasporous, Fritillaria type (in Calochortus and Streptopeae monosporous, Polygonum type; in Streptopus disporous, 8-nucleate, Allium type; in Clintonia and some Tulipa tetrasporous, Clintonia type; in some Erythronium and Tulipa tetrasporous, 8-nucleate, Adoxa type; in some Tulipa tetrasporous, 16-nucleate, Drusa type). Synergids sometimes with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells usually uninucleate. Endosperm development at least usually nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis onagrad, asterad or chenopodiad. Polyembryony sometimes present.

Fruit Usually a loculicidal capsule (sometimes septicidal or irregularly dehiscing; in Medeola, Prosartes, and Streptopus a berry).

Seeds Seed sometimes winged. Aril absent. Elaiosome sometimes present (developing from raphe and chalaza in Gagea, from raphe and hilum in Scoliopus). Seed coat testal. Testa thin (often with two cell layers), with thickened cells often flat or collapsed (sometimes with lignified walls). Exotesta in Medeola palisade. Tegmen usually strongly compressed (in Calochortus and Streptopeae two cell layers thick). Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, with aleurone and oils (starch absent), with thickened and pitted cell walls. Embryo usually small, little differentiated to well differentiated (embryo often growing after seed dispersal but prior to germination, e.g. in Cardiocrinum), without chlorophyll (Fritillaria, Tulipa). Cotyledon one, usually photosynthesizing, bifacial. Cotyledon hyperphyll usually elongate (sometimes compact), usually assimilating (sometimes not assimilating). Hypocotyl internode short or absent. Coleoptile absent. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology x = 6–14 (27) – Polyploidy and aneuploidy occurring. Chromosomes 1,5–19 µm long. The high level of variation in megagametophyte formation in Tulipa may depend on the use of apomictic and otherwise non-fertile cultivated material for most of the investigations.

DNA Plastid gene infA lost (Tricyrtis; pseudogene present). Very large genomes (with C value of c. 350 pg or more) found in some species.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (quercetin, kaempferol), flavanones, chalcones, tannins, steroidal alkaloids (in, e.g., Fritillaria and Notholirion), steroidal saponins (e.g. the sapogenins lilagenin and yuccagenin), tulipalines (α-methylene-γ-butyrolactone, a fungicide), glucose esters (tuliposides), saccharose esters of diferulic or triferulic acid, and fructans present. Ellagic acid, proanthocyanidins, cyanogenic compounds, and chelidonic acid not found.

Use Ornamental plants, medicinal plants, vegetables.

Systematics Liliaceae are sister-group to the clade [Smilacaceae+[Philesiaceae+Rhipogonaceae]].

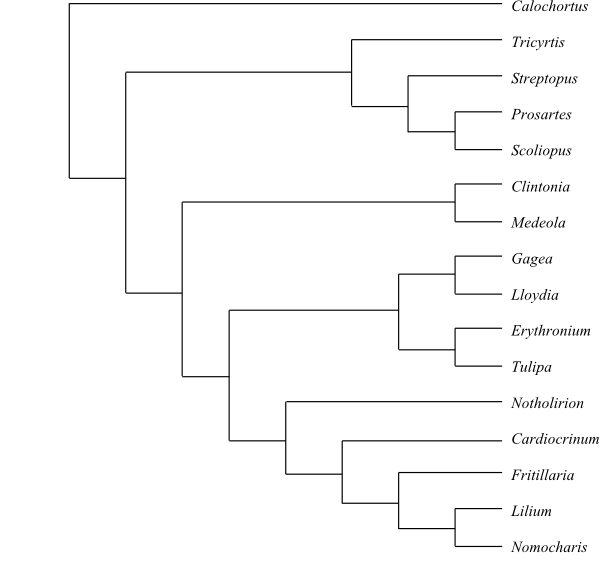

The tree below mainly follows Vinnersten & al. (2001) and Kim & al. (2013). Alternative phylogenies are found by, e.g., Patterson & Givnish (2002), Fay & al. (2006) and Peruzzi & al. (2009).

1/c 70? Calochortus (c 70?; temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere, with their highest diversity in western and eastern North America and East Asia. – Rhizomatous herbs. Bulb sometimes present. Vessels sometimes present in stem. Foliar venation parallelodromous, without reticulation. Flowers large. Tepals pubescent. Tepal nectaries saccate. Style developed, trifid. Placental epidermis papillate. Polar nuclei fusing prior to fertilization. Capsule sometimes septicidal. Seeds of various shape. Exotegmic and endotegmic cuticles developed. Hypocotyl short? n = 6–13; chromosomes 1,1–6,5(–15) μm long. γ-methylene glutamic acid sometimes present. – Calochortus s.lat. may not be a monophyletic group. – Both Calochortus and Streptopeae have an apically divided style. However, the support for the sister-group relationship [Calochortus+Streptopeae] is fairly low.

Streptopeae Baker in Gard. Chron., n.s., 2: 660. 21 Nov 1874

4/36. Tricyrtis (18; the Himalayas, China, the Korean Peninsula, Japan, Taiwan); Streptopus (10; central and southern Europe to the Himalayas, Tibet, East Asia, Siberia, Greenland, Canada, United States), Scoliopus (2; S. bigelovii, S. hallii; western United States), Prosartes (6; P. hookeri, P. lanuginosa, P. maculata, P. parvifolia, P. smithii, P. trachycarpa; southern and western Canada, United States). – Cold-temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere, with their largest diversity in eastern North America and East Asia. Rhizomatous herbs. Style developed, trifid. Megagametophyte development in Streptopus disporous, 8-nucleate, Allium type. Seeds striate. n = 8. – Tricyrtis appears to be sister to the clade [Streptopus+[Scoliopus+Prosartes]], although it has sometimes been recovered as sister to all other Liliaceae (with fairly low support).

Lilioideae Eaton, Bot. Dict., ed. 4: 27. Apr-Mai 1836 [‘Liliaceae’]

Medeoleae Benth. et Hook. f., Gen. Plant. 3: 750, 762. 14 Apr 1883

2/6. Medeola (1; M. virginiana; southeastern Canada, eastern United States), Clintonia (5; C. andrewsiana, C. borealis, C. udensis, C. umbellulata, C. uniflora; the Himalayas and Burma to China, the Korean Peninsula, Japan and the Russian Far East, Canada, western and eastern United States). – East Asia, North America. Fruit a berry. – Clintonia has a diploid endosperm. The megagametophyte has a tetrasporous development of special type: Clintonia type (also found in, e.g., some species of Tulipa).

Lilieae Lam. et DC., Syn. Plant. Fl. Gall.: 159. 30 Jun 1806 [’Liliaceae’]

9/460–490. Gagea (90–>>100; Europe, temperate Asia), Lloydia (10–12; Europe, temperate Asia, southwestern Canada, western United States), Tulipa (80–90; Europe, the Mediterranean, North Africa, West and Central Asia, China, with their highest diversity in southwestern Asia), Erythronium (27; Europe, temperate Asia, temperate North America, with their largest diversity in western North America), Fritillaria (130–140; Europe, the Mediterranean, temperate Asia to Japan); Notholirion (4–5; N. bulbiferum, N. koeiei, N. macrophyllum, N. thomsonianum; Afghanistan to western China), Cardiocrinum (3; C. cathayanum, C. cordatum, C. giganteum; the Himalayas, Tibet, northern Burma, East Asia), Lilium (c 110; temperate and subtropical regions on the Northern Hemisphere south to the Philippines; incl. Nomocharis?), Nomocharis (7–8; northern Assam, southestern Tibet, western China, northeastern Burma; in Lilium?). – Temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere, with their largest diversity in North America and East Asia. Roots often contractile. Bulb often present. Stem simple. Venation usually parallelodromous, without reticulation. Flowers often large. Median outer tepal adaxial? Style entire or absent. Stigma crested. Megagametophyte tetrasporous (Fritillaria type, with three chalazal megaspores fusing and two subsequent cell divisions; Adoxa and Drusa types also observed). Capsule septicidal. Seeds often flattened. Elaiosome sometimes present. Funicle long. Seed coat testal-tegmic. Exotesta palisade or lignified. Tegmen also persistent. Endosperm thick-walled, often pentaploid, in Erythronium without pits. Cotyledon sometimes unifacial. n = 9, 11–14; chromosomes (1,1–)5–27 μm long. Steroidal alkaloids (sometimes present), tuliposides, di- and triferulic acid saccharose esters, and γ-methylene glutamic acid present.

|

Cladogram of Liliaceae based on DNA sequence data (Vinnersten & Bremer 2001, etc.; Kim & al. 2013). Nomocharis is nested inside Lilium, according to Gao & al. (2012). Streptopeae are sister-group to the remaining Liliaceae, according to Kim & al. (2013), and Calochortus sister to the rest, although with weak support. |

LUZURIAGACEAE Lotsy |

( Back to Liliales ) |

Genera/species 2/5

Distribution Easternmost and southeasternmost Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand, Stewart Island, Peru to Tierra del Fuego, the Falkland Islands.

Fossils The fossil flowers Luzuriaga peterbannisteri and Liliacidites contortus were reported from Early Miocene layers in New Zealand. The fossil Acaciaephyllum spatulatum from the Potomac Formation resembles extant Luzuriagaceae in its foliar anatomy.

Habit Bisexual, perennial herbs, often with more or less lignified stem. Twining, climbing or epiphytic.

Vegetative anatomy Roots fibrous, with uniseriate exodermis. Phellogen? Cortex with a ring of fibre bundles and small collateral vascular bundles; centre of stem with scattered vascular bundles. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels present in roots and stem. Vessel elements with scalariform or simple perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays? Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals. Nodes? Laticifers and mucilage cells absent. Tanniniferous cells present in Drymophila. Silica bodies absent. Calciumoxalate raphides and druses present in Drymophila.

Trichomes Hairs absent.

Leaves Alternate (distichous), simple, entire, resupinate (twisted 180º at base), with conduplicate or supervolute ptyxis. Stipules absent; leaf sheath open or absent. Venation parallelodromous, acrodromous, with three to five longitudinal primary veins (mid-vein distinct) and transversal and reticulate secondary and tertiary veins (in Drymophila with free ends). Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids as stalk-like structures (Convallaria type?). Mesophyll with mucilaginous idioblasts containing calciumoxalate raphides. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Axillary, few-flowered cincinnus, or flowers solitary.

Flowers Actinomorphic. Pedicel articulated. Hypogyny. Tepals 3(–4)+3(–4), petaloid, persistent (Luzuriaga) or caducous (Drymophila), free. Tepal nectaries present at tepal bases. Septal nectaries absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens 3+3. Filaments filiform, free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse or extrorse, usually longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); in some species of Luzuriaga poricidal (dehiscing by apical pores). Tapetum amoeboid-periplasmodial, binucleate (Drymophila). Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive (Drymophila). Pollen grains monosulcate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, reticulate or finely foveolate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of usually three (rarely four) connate carpels. Ovary superior, usually trilocular (rarely unilocular or quadrilocular). Style single, in Luzuriaga simple, in Drymophila deeply trilobate. Stigma single, capitate, Dry type (Luzuriaga), or stigmas three, Wet type (Drymophila). Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation axile or subparietal. Ovules three to nine per carpel, hemianatropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal. Outer integument ? cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development nuclear? Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A berry, in Luzuriaga with persistent tepals.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa and tegmen thin-walled. Exotesta collapsing, sometimes caducous. Endotesta? Tegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, with thick-walled cells, with aleurone and oil (starch absent). Embryo straight, chlorophyll? Cotyledon one, little differentiated, not photosynthesizing? Cotyledon hyperphyll compact, not assimilating. Hypocotyl internode short. Coleoptile absent. Radicula well developed, persistent. Epicotyl elongate. Ligule absent. Germination?

Cytology x = 10 – Karyotype bimodal.

DNA

Phytochemistry Virtually unknown. Chelidonic acid present. Alkaloids? Steroidal saponins? Flavonols, ellagic acid, proanthocyanidins, and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Ornamental plants, ropes (Luzuriaga radicans).

Systematics Luzuriaga (4; L. marginata, L. polyphylla, L. radicans: southern Chile, Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego, Falkland Islands; L. parviflora: New Zealand incl. Stewart Island), Drymophila (2; D. cyanocarpa: southern New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania; D. moorei: southeastern Queensland, northeastern New South Wales).

Luzuriagaceae are sister to Alstroemeriaceae.

Drymophila has resupinate leaves, twisted 180° at base. Its taxonomic position has been uncertain, although it was identified as sister to Luzuriaga in the analyses by Kim & al. (2013).

MELANTHIACEAE Borkh. |

( Back to Liliales ) |

Veratraceae Salisb. in Trans. Linn. Soc. London 8: 10. 1807 [’Veratreae’]; Paridaceae Dumort., Fl. Belg.: 131. 1827 [’Parideae’]; Trilliaceae Chevall., Fl. Gén. Env. Paris 2: 297. 1827, nom. cons.; Melanthiales Link, Handbuch 1: 145. 4-11 Jul 1829 [‘Melanthaceae’]; Paridales Link, Handbuch 1: 277. 4-11 Jul 1829 [‘Parideae’]; Veratrales Dumort., Anal. Fam. Plant.: 59. 1829 [’Veratrarieae’]; Heloniadaceae J. Agardh, Theoria Syst. Plant.: 4. Apr-Sep 1858 [’Helonieae’]; Chionographidaceae (Nakai) Takht. in Bot. Žurn. 81(2): 85. Mai-Jun 1996; Xerophyllaceae Takht. in Bot. Žurn. 81(2): 86. Mai-Jun 1996; Trilliales Takht., Divers. Classif. Fl. Pl.: 485. 24 Apr 1997; Melanthianae Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.: lv. 23 Dec 2001

Genera/species 17/175–180

Distribution Europe, the Mediterranean, temperate Asia, the Himalayas, northeastern India, East Asia, Burma, Indochina, North America to the northern Andes.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, andromonoecious, polygamous, dioecious, androdioecious, or gynodioecious, evergreen or deciduous perennial herbs (rarely somewhat lignified at base). Sometimes with a bulb without nutrient-storing scales (in some species of Schoenocaulon a corm).

Vegetative anatomy Roots fibrous. Phellogen absent. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels present in roots. Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals. Nodes? Idioblasts with calciumoxalate raphides, druses or single crystals.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or absent.

Leaves Alternate (in Parideae seemingly verticillate), simple, entire, with usually ? (sometimes curved-plicate) ptyxis, sometimes differentiated into pseudopetiole and pseudolamina. Stipules absent; leaf sheath sometimes well developed. Venation parallelodromous or palmatireticulate, acrodromous, with primary veins connected by reticulate veins (Parideae). Stomata anomocytic (in Parideae with four cells). Cuticular wax crystalloids as parallel platelets with indistinct orientation or absent. Mesophyll with idioblasts containing calciumoxalate as raphides and single prismatic crystals. Leaf margin usually entire (sometimes serrate).

Inflorescence Terminal, panicle, umbel-like, botryoid and raceme-like, or stachyoid and spike-like, simple or branched, or flowers solitary. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) absent.

Flowers Usually actinomorphic (in Chionographis zygomorphic). Usually hypogyny (in Stenanthium and sometimes Zigadenus half epigyny; in some species of Veratrum epigyny). Tepals usually 3+3, 4+4, 5+5 or 6+6 (rarely three, four or more than twelve), with imbricate or contorted (inner tepals in Parideae) aestivation, sepaloid or petaloid (in Parideae differentiated into outer sepaloid and inner petaloid tepals), persistent or caducous (in Melanthium clawed), usually free (sometimes connate at base). Tepal nectaries often (e.g. in Trillium, Veratrum and Zigadenus) present at inner tepal bases. Septal nectaries usually absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens usually as many as tepals (rarely up to 24 in six whorls), in Parideae usually persistent. Filaments filiform to subulate, free from each other and usually free from tepals (sometimes adnate to tepal bases). Anthers basifixed or dorsifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, usually extrorse (rarely latrorse or introrse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits or flaps); connective in, e.g., Parideae with long apical appendage. Tapetum secretory, with binucleate cells. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains usually monosulcate or inaperturate (in Chamaelirium and Chionographis tetraporate; in Trillium omniaperturate), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate (rarely intectate), with columellate infratectum, reticulate, foveolate, clavate, gemmate, corrugate, verrucate, echinate, spinulate, or psilate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of three (to ten) more or less connate carpels (in Amianthium and Stenanthium in lower part only, otherwise half-way or largely connate; rarely one carpel). Ovary usually superior (sometimes semi-inferior, rarely inferior), usually trilocular (to decemlocular) at least in lower part (rarely unilocular). Style single, simple, or stylodia free. Stigma single, capitate, or stigmas three adaxial, more or less papillate, usually Dry (rarely Wet) type. Pistillodium absent?

Ovules Placentation usually axile (rarely parietal, when ovary unilocular). Ovules two to more than 50 per carpel, anatropous or campylotropous, apotropous? or epitropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal. Outer integument ? cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Nucellar cap, formed by periclinal divisions of apical megasporangial epidermal cells, present in at least Amianthium, Chionographis and Trillium. Parietal cell formed from archesporial cell (at least in some genera; parietal tissue one or two cell layers thick). Megagametophyte usually monosporous, Polygonum type (in Veratrum monosporous, modified Polygonum type, or disporous, Allium type or Veratrum lobelianum type: an ephemeral triad formed during second meiotic division, since micropylar cells divides earlier than chalazal cell; in Parideae usually disporous, Allium or Scilla type). Synergids in Amianthium with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells inAmianthium, Heloniopsis and Veratrum multinucleate, proliferating (in Veratrum). Endosperm development usually helobial (in Paris nuclear). Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis asterad (Heloniopsis).

Fruit A berry (many species in Parideae) or a loculicidal and/or septicidal or ventricidal (in Veratreae) capsule (in some species of Trillium irregularly dehiscing) with persistent tepals.

Seeds Aril or sarcotesta present in some species of Parideae. Testa sometimes winged or with terminal appendages, caudate. Phlobaphene present in at least Amianthium. Exotesta? Endotesta? Tegmen collapsed. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, with aleurone and oils (sometimes also with starch grains). Embryo usually small (rarely large), well or little differentiated, without chlorophyll. Cotyledon one, unifacial or bifacial. Cotyledon hyperphyll elongate, assimilating. Hypercotyl internode short or absent. Coleoptile absent. Radicula little differentiated. Germination?

Cytology n = 5, 8, 10–12, 15–17, 21, 22, 27 – Polyploidy occurring in, e.g., Veratrum and Parideae. Chromosomes usually 1–6 µm long (in Parideae 6–>40 μm long).

DNA Very large genomes (with a C value of c. 350 pg or more) are found in some species.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), flavones, luteolin, apigenin, etc., tannins, steroidal alkaloids (ceveratrum and jerveratrum alkaloids, veratramine, zigadenine, jervine, etc.), steroidal saponins, anthraquinones, and chelidonic acid present. Ellagic acid and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Ornamental plants, medicinal plants (Veratrum etc.), insecticides (Schoenocaulon).

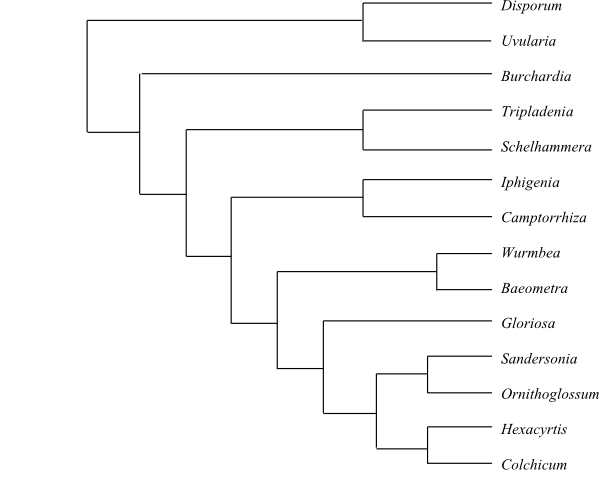

Systematics Melanthiaceae are sister-group to Petermannia (Petermanniaceae), according to Kim & al. (2013).

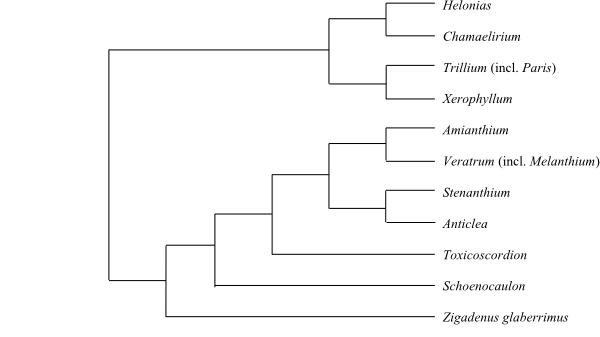

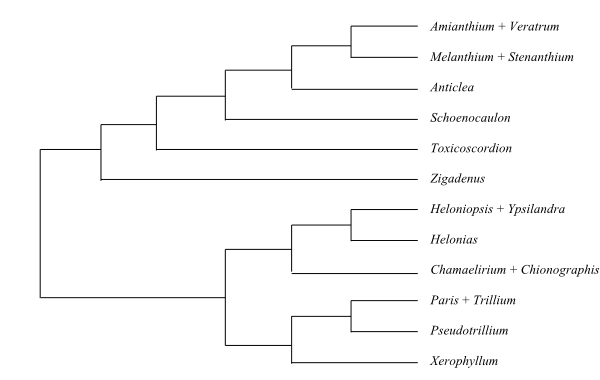

Melanthieae Griseb., Spic. Fl. Rumel. 2: 377. Jan 1846

8/80–85. Zigadenus (1; Z. glaberrimus; southeastern United States), Toxicoscordion (9; southern Canada, western and central United States), Schoenocaulon (c 25; Florida, Mexico, Central America, northern South America to Peru), Anticlea (11; Mongolia, China, the Korean Peninsula, Japan, the Russian Far East, Canada, United States, Mexico, Central America to Guatemala), Stenanthium (5; S. densum, S. diffusum, S. gramineum, S. leimanthoides, S. occidentale; southeastern and eastern United States), Melanthium (4; M. latifolium, M. parviflorum, M. virginicum, M. woodii; central and eastern United States; in Veratrum?), Veratrum (25–30; temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere), Amianthium (1; A. muscitoxicum; eastern United States). – Temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere and southwards to the Andes in Peru. Bulb present (in Amianthium with very toxic substances). Leaves sometimes with curved-plicate ptyxis. Leaf sheath in Veratrum closed. Anthers reniform, dehiscing by valves. Capsule septicidal-ventricidal. n = 8 (10, 11, 16). Strongly oxygenated esterified C-nor-D-homosteroidal alkaloids. Alkaloids in Veratrum and its closest relatives are very complex and typical.

[Heloniadeae+Chionographideae]

Stevens (2001 onwards) lists the following characters: cuboid calciumoxalate crystals; inflorescence without bracts; confluent thecae; and intectate exine.

Helonias

3/13. Helonias (1; H. bullata; eastern United States), Heloniopsis (6; H. kawanoi, H. koreana, H. leucantha, H. orientalis, H. tubiflora, H. umbellata; the Korean Peninsula, Japan, Sakhalin, Taiwan), Ypsilandra (6; Y. alpina, Y. cavaleriei, Y. jinpingensis, Y. kansuensis, Y. thibetica, Y. yunnanensis; the Himalayas, Tibet, western China, Burma, northern Vietnam, Taiwan). – Eastern United States, the Himalayas, East Asia. Raphides absent. Pollen grains with spinulate exine. Seeds linear, at each end with a long caudate appendage. n = 17.

Chionographideae Nakai, Chosakuronbun Mokuroku [Ord. Fam. Trib. Nov.]: 229. 20 Jul 1943

2/7. Chamaelirium (1; C. luteum; eastern United States), Chionographis (6; C. chinensis, C. hisauchiana, C. japonica, C. koidzumiana, C. merrilliana, C. shiwandashanensis; southern China to Japan). – Eastern United States, East Asia. Flowers often unisexual. Tepal one-veined. Pollen grains tetraporate. Exine with clavate processes. Capsule septicidal. Seeds winged (sometimes at one end only). n = 12 (21, 22).

[Xerophylleae+Parideae]

Characterized by distinct thecae (Stevens 2001 onwards).

Xerophylleae S. Watson in Proc. Amer. Acad. Arts 14: 225. 2 Aug 1879

1/2. Xerophyllum (2; X. asphodeloides: eastern United States; X. tenax: western North America). – Bulb present. Pericycle two or three cell layers thick. Leaves long and linear, xeromorphic. Tepal nectaries absent. Styloids present. Ovules two to four per carpel. n = 15. – Xerophyllum is anatomically very distinct and adapted to arid conditions.

Parideae Bartl., Ord. Nat. Plant.: 53. Sep 1830 [‘Paridea’]

3/c 73. Pseudotrillium (1; P. rivale; Siskiyou Mountains in southern Oregon and northern California, usually on ultrabasic soils), Trillium (c 45; temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere), Paris (27; Eurasia to Southeast Asia, with the highest diversity in China). – Temperate and mountainous regions on the Northern Hemisphere. Rhizome monopodial. Root hypodermis dimorphic. Raphides absent. Cuboidal crystals present. Stomata tetracytic. Leaves verticillate, with mid-vein, pseudolamina and sometimes pseudopetiole. Flowers solitary, terminal, up to 12-merous. Hypogyny. Outer tepals three to ten, sepaloid, free (sometimes absent). Inner petals three to six (to eight), petaloid, free (sometimes absent). Septal nectaries sometimes present. Stamens six to 24. Anthers introrse, latrorse or extrorse. Pistil composed of three (to ten) connate carpels. Ovary superior. Style branched or simple. Stigma Dry type. Placentation axile to parietal. Ovules usually numerous per carpel, with various positions, crassinucellar. Nucellar cap two to four cell layers thick. Parietal tissue one or two cell layers thick. Megagametophyte usually disporous, 8-nucleate, Allium or Scilla type. Endosperm development nuclear or helobial. Berry or usually loculicidal (sometimes also septicidal) capsule, often with persistent tepals and stamens. Aril or sarcotesta sometimes present. Embryo very small, undifferentiated (prior to germination growing to approx. the length of the seed). Cotyledon unifacial, sometimes differentiated into pseudopetiole and pseudolamina. n = 5; chromosomes heteromorphic, 6–>40 μm long. Flavonols present.

|

Cladogram of Melanthiaceae based on DNA sequence data (Zomlefer & al. 2001). |

|

Cladogram of Melanthiaceae based on DNA sequence data (Kim & al. 2016). |

PETERMANNIACEAE Hutch. |

( Back to Liliales ) |

Genera/species 1/1

Distribution Easternmost Australia.

Fossils The fossil species Petermanniopsis angleseaensis (with paracytic stomata) from the Eocene of Victoria resembles the extant Petermannia cirrosa.

Habit Bisexual, perennial herb with lignified rhizome. Aerial stem climbing, with spines and branched leaf-opposite tendrils.

Vegetative anatomy Roots fibrous, with uniseriate velamen. Phellogen? Cortex with a cylinder of fibre bundles and small collateral vascular bundles; centre of stem with scattered bundles. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels present in roots, stem and sometimes leaves. Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays absent? Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals. Nodes? Calciumoxalate raphides abundant.

Trichomes Hairs absent; prickles abundant on stem.

Leaves Alternate (spiral), simple, entire, linear, differentiated in pseudopetiole and pseudolamina, with conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Venation pinnate-campylodromous, with three to five longitudinal primary veins connected by reticulate secondary and tertiary veins. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Mesophyll with cells containing calciumoxalate raphides. Tanniniferous cells present. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal (gradually leaf-opposed due to growth of axillary sympodial shoot), panicle or raceme-like. Inflorescence partially transformed into tendrils.

Flowers Actinomorphic. Pedicel not articulated. Epigyny. Tepals 3+3, petaloid to sepaloid, caducous, free or connate at base into a tube. Tepal nectaries present at tepal bases. Septal nectaries absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens 3+3. Filaments filiform, free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile?, tetrasporangiate, extrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum amoeboid-periplasmodial, with binucleate cells. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains monosulcate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate? infratectum, spinulate. Pollen grains containing starch.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of three connate carpels. Ovary inferior, unilocular (sometimes incompletely trilocular due to placental fusion). Style single, simple, long, narrow. Stigma capitate, slightly trilobate, Wet type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation parietal. Ovules c. 15 to more than 50 per ovary, anatropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle ?-stomal. Outer integument ? cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Parietal cell formed from archesporial cell. Nucellar cap formed by periclinal divisions in megasporangial epidermis. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A many-seeded berry.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat testal. Exotesta and endotesta thickened. Mesotesta several cell layers thick. Cuticle present between testa and tegmen. Tegmic cells collapsed (crushed), thin-walled. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, without starch. Embryo straight, chlorophyll? Cotyledon one, compact. Cotyledon hyperphyll? Hypocotyl internode? Coleoptile? Radicula well developed. Primary leaves cataphylls. Germination?

Cytology n = 5

DNA

Phytochemistry Virtually unknown. Saponins not found.

Use Unknown.

Systematics Petermannia (1; P. cirrosa; southeastern Queensland, northeastern New South Wales).

Petermannia is sister to Melanthiaceae, according to Kim & al. (2013).

PHILESIACEAE Dumort. |

( Back to Liliales ) |

Lapageriaceae Kunth, Enum. Plant. 5: 283. 10-11 Jun 1850 [’Lapagerieae’]

Genera/species 2/2

Distribution Southern Chile.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, suffrutex (Philesia) or liana (Lapageria). Aerial roots absent. Rhizome, when present, short, woody, sometimes branched.

Vegetative anatomy Roots fibrous. Velamen present. Phellogen? Cortex with a cylinder of fibre bundles and small collateral vascular bundles; centre of stem with scattered bundles. Secondary lateral growth anomalous? Vessels present or absent in roots and/or stem. Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays? Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals. Nodes? Tanniniferous cells, mucilage cells and laticifers absent. Silica bodies absent. Calciumoxalate present as raphides.

Trichomes Hairs absent.

Leaves Alternate (spiral or distichous), simple, entire, coriaceous or scleromorphic, differentiated into pseudopetiole and pseudolamina or almost ericoid, with conduplicate-flat or curved ptyxis; pseudolamina resupinated (twisted 180° at base). Stipules absent; leaf sheath more or less developed. Venation parallelodromous (seemingly palmate), acrodromous; secondary veins reticulate or transversal. Stomata anomocytic (in Philesia transversely oriented relative to foliar long axis). Cuticular wax crystalloids as parallel or non-orientated platelets. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, few-flowered, or flowers solitary and pendant. Pedicel usually with many scale-like bracts and floral prophylls (bracteoles).

Flowers Actinomorphic, often large. Pedicel not articulated. Hypogyny. Tepals 3+3, all petaloid (Lapageria) or outer tepals sepaloid and inner tepals petaloid and spotted on adaxial side (Philesia), caducous, usually free (sometimes connate at base), forming an infundibuliform or campanulate perianth; perianth tube absent. Nectar secreted from pouch-shaped nectaries on tepal bases (tepal nectaries). Septal nectaries absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens 3+3. Filaments free (Lapageria) or connate in lower half into a tube (Philesia), free from tepals. Anthers subbasifix, non-versatile?, tetrasporangiate, extrorse (Philesia) or introrse (Lapageria), poricidal (dehiscing by pores). Tapetum probably secretory. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains inaperturate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with granular infratectum, spinulate to echinulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of three connate carpels. Ovary superior, unilocular. Style single, simple, filiform, with stylar canal. Stigma capitate or slightly trilobate, papillate, Dry (Philesia) or Wet (Lapageria) type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation intrusively parietal. Ovules ten to more than 100 per ovary, anatropous or amphitropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal. Outer integument ? cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Megasporangial epidermis with periclinal and anticlinal cell divisions. Parietal cell formed from archesporial cell. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Synergids with a filiform apparatus. Endosperm development nuclear? Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A few- to many-seeded berry.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed exotegmic-endotegmic. Testa thin, collapsed. Exotegmen? Endotegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, with oils and aleurone, with thin cell walls. Embryo well differentiated, straight, chlorophyll? Cotyledon one, not photosynthesizing. Cotyledon hyperphyll compact, not assimilating. Hypocotyl internode short. Coleoptile absent. Radicula well developed, persistent. Primary leaf a dorsiventral cataphyll, alternating with cotyledon. Germination?

Cytology n = 15 (Lapageria); n = 19 (Philesia) – Chromosomes 2,5–12 µm long.

DNA

Phytochemistry Very insufficiently known. Steroidal saponins (diosgenin) present in Philesia. Chelidonic acid? Stem fructans not found.

Use Ornamental plants.

Systematics Philesia (1; P. magellanica; southern Chile), Lapageria (1; L. rosea; southern Chile, adjacent parts of Argentina).

Philesiaceae are sister to Rhipogonum (Rhipogonaceae).

RHIPOGONACEAE Conran et Clifford |

( Back to Liliales ) |

Genera/species 1/6

Distribution New Guinea, eastern Australia, New Zealand.

Fossils Fossil Rhipogonum is known from the Early Eocene in Tasmania and South America, and from the Early Eocene to the Miocene in New Zealand.

Habit Bisexual, evergreen shrubs or lianas with short rhizome and without tendrils. Lateral ligules and/or spines present. Aerial roots absent.

Vegetative anatomy Roots fibrous. Root exodermis with thickened cell walls. Phellogen ab initio superficial? Cortex with a cylinder of fibre bundles and small collateral vascular bundles. Rhizome with specialized layer of spirally arranged vascular strands. Stem bundles arranged in a cylinder; two leaf traces arising from each node and connected with one another, stem vascular tissue originating from leaf traces. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels present in roots and stem. Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays? Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals. Nodes ?:2, ?-lacunar with two leaf traces. Laticifers absent. Tanniniferous cells present. Secretory cavities with mucilage often present. Calciumoxalate as raphides.

Trichomes Hairs absent.

Leaves Usually alternate (distichous) or opposite (sometimes verticillate), simple, entire, usually coriaceous, differentiated into pseudopetiole and pseudolamina, with conduplicate or curved ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Pseudopetiole without tendrils or spines. Venation parallelodromous, acrodromous or campylodromous (or brochidodromous?), with five longitudinal primary veins and reticulate fine venation with sometimes free vein endings. Stomata anomocytic (mesoperigenous). Cuticular wax crystalloids as parallel platelets? Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, simple or compound paniculate, often raceme- or spike-like.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Hypogyny. Pedicel not articulated. Tepals 3+3, petaloid, caducous, free. Tepal nectaries present at tepal bases. Septal nectaries absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens 3+3. Filaments free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, latrorse or introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum amoeboid-periplasmodial, with binucleate cells. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains monosulcate, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine semitectate, thin, with columellate infratectum, reticulate and somewhat foveolate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of three connate carpels. Ovary superior, trilocular. Style single, simple, short, or absent. Stigma trilobate, papillate, Wet type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation basal or axile. Ovules two per carpel, anatropous, pendulous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle ?-stomal. Outer integument ? cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Megasporangial epidermis with periclinal and anticlinal cell divisions. Parietal cell formed from archesporial cell. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum-type. Antipodal cells two to six. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A many-seeded berry.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat tegmic. Testa degenerating? Thick cuticle present between testa and tegmen (and on inner tegmic epidermis?). Tegmen well developed? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, with thickened cell walls?, with starch, aleurone and oils. Embryo straight, well differentiated, small, chlorophyll? Cotyledon one, not photosynthesizing. Cotyledon hyperphyll compact, not assimilating. Hypocotyl internode not elongate. Epicotyl long. Coleoptile absent. Ligule absent. Radicula well developed, persistent. Germination?

Cytology n = 15 – Karyotype bimodal.

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), tannins, steroidal saponins, and chelidonic acid present. Ellagic acid, proanthocyanidins, and stem fructans not found.

Use Basketry.

Systematics Rhipogonum (6; R. album, R. brevifolium, R. discolor, R. elseyanum, R. fawcettianum: eastern Queensland, eastern New South Wales, R. album also in eastern Victoria and on New Guinea; R. scandens: New Zealand on North Island, South Island, Stewart Island and Chatham Islands).

Rhipogonum is sister to Philesiaceae.

SMILACACEAE Vent. |

( Back to Liliales ) |

Genera/species: 1–2/310–360

Distribution Tropical, subtropical and temperate regions on both hemispheres.

Fossils Fossil leaves referred to Smilax are known from the Maastrichtian, the Eocene and the Miocene.

Habit Usually dioecious, twining evergreen shrubs, suffrutices or perennial herbs. Tuberous stem present in some species. Lateral ligules and/or spines or pairwise petiolar tendrils present. Aerial roots absent. Rhizome woody.

Vegetative anatomy Roots fibrous. Root exodermis with unthickened cell walls. Phellogen ab initio superficial? Cortex with a cylinder of fibre bundles and small collateral vascular bundles. Stem vascular bundles cylindrically arranged. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels usually present at least in roots and stem (in some species of Heterosmilax also in leaves). Vessel elements with scalariform or simple perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays? Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals. Nodes?, with three main bundles often entering leaf base. Laticifers absent. Tanniniferous cells present. Secretory cavities with mucilage often present. Silica bodies absent. Mucilage cells with calciumoxalate raphides abundant in rhizome and tuberous stem.

Trichomes Hairs usually absent; prickles (often large and spine-like) present in numerous species.

Leaves Usually alternate (spiral or distichous; sometimes opposite), simple, entire, usually coriaceous, differentiated into pseudopetiole and pseudolamina, with conduplicate or supervolute-involute ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Pseudopetiole often with pair of tendrils or spines. One pair of pseudostipules (stipule-like outgrowths) often present at pseudopetiole base. Venation parallelodromous, acrodromous or campylodromous (brochidodromous at margins), with five to seven stout longitudinal primary veins and reticulate fine venation with sometimes free vein endings. Stomata anomocytic or irregular. Cuticular wax crystalloids as usually parallel (sometimes non-orientated) platelets. Leaf margin entire. Extrafloral nectaries sometimes present on abaxial side of pseudolamina.

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, simple or compound, often umbel-, raceme- or spike-like.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Hypogyny. Pedicel not articulated. Tepals 3+3, petaloid to sepaloid, caduous, usually free (in Heterosmilax connate into a tube). Tepal nectaries often present on inner tepal bases in male flowers. Septal nectaries absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens usually 3+3 (in Heterosmilax three in one whorl or nine, twelve, 15 or 18 in several whorls). Filaments usually free from each other (sometimes entirely or partially connate into a tube), free from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, disporangiate (dithecal or sometimes confluent and seemingly monothecal), latrorse or introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory, with binucleate cells. Female flowers often with staminodia. Nectariferous hairs often present on stamens.