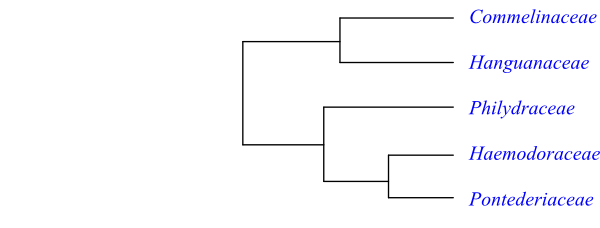

Cladogram of Commelinales based on DNA sequence data (Saarela & al. 2008).

Habit Usually bisexual (sometimes monoecious or andromonoecious, rarely polygamomonoecious), usually perennial (rarely annual) herbs. Usually somewhat succulent, sometimes twining, very rarely epiphytic. Bulb, corm or tuber rarely present. Often aquatic or helophytic.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza not found. Phellogen absent. Primary vascular tissue cylinder of bundles, or two or several cylinders, or scattered bundles. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels in roots, and sometimes stems and/or leaves. Vessel elements usually with scalariform (sometimes simple or reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform or alternate, simple or bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids with simple pits. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals, without starch or protein filaments. Nodes usually multilacunar with several leaf traces. Mucilage ducts and chambers with cells containing calciumoxalate raphides. Latex rarely present. Tanniniferous (sometimes lignified) idioblasts sometimes present. Silica bodies usually absent. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals rarely present.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, usually uniseriate (rarely multiseriate), simple or branched; tricellular glandular microhairs present in most clades.

Leaves Alternate (usually spiral, sometimes distichous), simple, entire, usually linear, sometimes equitant (ensiform), rarely subulate, with conduplicate, involute, convolute or supervolute (rarely plicate) ptyxis, sometimes differentiated into pseudopetiole and pseudolamina. Stipules absent; leaf sheath closed, open or absent (rarely reduced to ligule). Colleters sometimes present. Venation (pinnate-)parallelodromous, sometimes acrodromous. Stomata paracytic, tetracytic or hexacytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids as aggregated rodlets (Strelitzia type), non-aggregated rodlets or absent. Epidermis thick, sometimes with idioblasts containing silica bodies. Mesophyll often with mucilaginous idioblasts or mucilage canals containing calciumoxalate raphides (mesophyll rarely with tanniniferous idioblasts). Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, panicle, thyrse, or corymb, often composed of cincinni, sometimes raceme-, head- or spike-like (flowers rarely solitary). Bracts sometimes large, sometimes boat-shaped. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) sometimes lateral or absent.

Flowers Actinomorphic or zygomorphic. Hypogyny, epigyny or half epigyny. Tepals usually 3+3 (sometimes 2+2, rarely 3+2); outer tepals usually with imbricate (rarely valvate) aestivation, sepaloid or petaloid, free or more or less connate; inner tepals with usually imbricate (rarely valvate) aestivation, usually petaloid (rarely sepaloid), thin, often stipitate, free or more or less connate (sometimes into tube); when zygomorphic, then median inner tepal often abaxial. Nectary absent, or septal nectaries inserted below insertion point of tepals or present on staminodia. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens 3+3, two to four of which often staminodial, or three fertile stamens and no staminodium (sometimes one fertile stamen and two staminodia, or one stamen and no staminodium). Filaments glabrous or entirely or partially covered with long and usually moniliform hairs, free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed to dorsifixed, sometimes versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse, latrorse, or extrorse, usually longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits; rarely poricidal, dehiscing by apical pores). Tapetum usually amoeboid-periplasmodial (sometimes secretory). Staminodia absent or alternating with stamens (antesepalous or antepetalous), or inserted on only one (anterior or posterior) side of flower, and stamens on opposite side; female flowers with staminodia.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains usually monosulcate (sometimes disulcate to tetrasulcate, or monosulculate to trisulculate, rarely inaperturate, diporate, triporate, heptaporate or octoporate), usually shed as monads (rarely tetrads or polyads), bicellular or tricellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or intectate, usually with columellate (sometimes acolumellate) infratectum, verrucate, rugulate, spinulate or granulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (one to) three connate carpels. Ovary superior, inferior or semi-inferior, unilocular or entirely or partially bilocular or trilocular. Style single, simple, straight or curved, usually narrow. Stigma simple, small or large, punctate, capitate, penicillate, triangular or somewhat trilobate, papillate or non-papillate, Dry or Wet type. Male flowers often with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation usually axile (rarely parietal or basal). Ovules one to more than 50 (to more than 100) per carpel, orthotropous, hemianatropous or campylotropous (sometimes hypotropous, pleurotropous, anatropous or irregular), ascending or pendulous, apotropous, epitropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar or weakly crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal or bistomal (sometimes exostomal). Funicular obturator sometimes present. Parietal cell usually formed from archesporial cell (sometimes further dividing forming parietal tissue). Nucellar cap sometimes present. Periclinal divisions sometimes taking place in megasporangial epidermis (then parietal cell not formed). Megagametophyte monosporous, usually Polygonum type (rarely disporous, Allium type, or tetrasporous, Adoxa, Oenothera or Scilla types). Synergids sometimes with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells ephemeral, not proliferating. Endosperm development nuclear or helobial. Cell wall formation in small chalazal chamber preceding that in large micropylar chamber. Endosperm haustoria micropylar or absent. Embryogenesis asterad or onagrad.

Fruit A loculicidal or poricidal capsule (rarely irregularly dehiscent or indehiscent, a nut, or a schizocarp with nut-like mericarps), a berry-like capsule or berry.

Seeds Aril sometimes present. Seed coat testal-tegmic. Exotesta sometimes with pigmented outer epidermis, sometimes collapsed, sometimes with thick cell walls. Endotestal cells often with silica bodies. Tegmic cells sometimes compressed, sometimes degenerating or crushed. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, starchy, often also with lipids and aleurone. Embryo small, straight, situated opposite hilum (often near micropyle), usually well differentiated, often covered with discoid or conical embryostega, testal operculum, usually surrounded by micropylar collar, without chlorophyll, Xyris-Scirpus or Trillium type. Cotyledon usually one (sometimes two, one of which rudimentary). Cotyledon hyperphyll elongate or compact, often assimilating. Hypocotyl internode short to long, or absent. Mesocotyl usually absent. Coleoptile often present. Collar rhizoids usually present. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 4–17, 19–21, 24, 26, 28–30, 36, 37, 40, 41, >45

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, syringetin), O-methylated flavonols, 6-hydroxyflavonoids (6-hydroxyluteolin), flavone-C-glycosides, cyanidin, cyanidin-3,7,3’-triglycoside, delphinidin, proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins), phenolic acids, chelidonic acid, tyrosine-derived cyanogenic compounds, phenylphenalenones (perinaphthenones), arylphenalenones, polyamines, and fructans present. Ferulic or diferulic acids and p-coumaric acids often present in cell walls. Alkaloids and steroidal saponins rare. Ellagic acid not found.

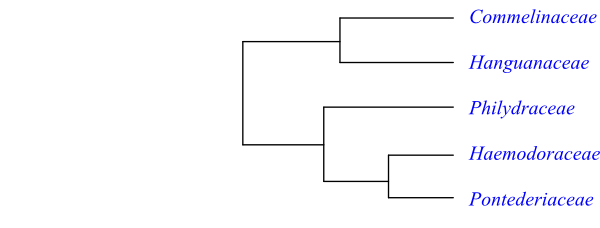

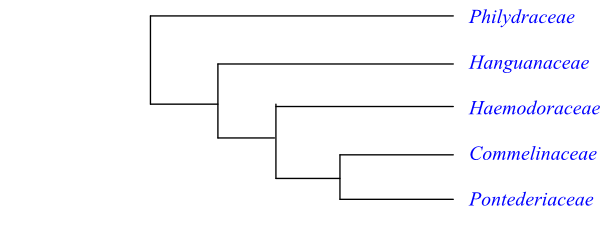

Systematics Commelinales are sister-group to Zingiberales. Two main clades were discerned by Saarela & al. (2008), one comprising Commelinaceae and Hanguanaceae, and another clade including Philydraceae, Haemodoraceae and Pontederiaceae. Both Commelinaceae and Hanguanaceae have a non-photosynthesizing (non-chlorophyllous) cotyledon.

Stevens (2001 onwards) lists the following potential synapomorphies of the clade [Philydraceae+[Haemodoraceae+Pontederiaceae]]: absence of silica bodies; presence of styloids; perianth with tanniniferous cells; perianth persistent in fruit; and placentae containing sclereids. Haemodoraceae and Pontederiaceae have the following characters in common (Stevens 2001 onwards): ectexine not tectate or columellate; endothecial cells with basal plates; and presence of phenylphenalenones (also found in some clades of Cannales).

|

Cladogram of Commelinales based on DNA sequence data (Saarela & al. 2008). |

|

Cladogram of Commelinales based on DNA sequence data (Janssen & Bremer 2004). |

COMMELINACEAE Mirb. |

( Back to Commelinales ) |

Ephemeraceae Batsch, Tab. Affin. Regni Veg.: 125. 2 Mai 1802 [‘Ephemera’], nom. illeg.; Tradescantiaceae Salisb. in Trans. Linn. Soc. London 8: 9. 1807 [‘Tradescanteae’]; Ephemerales Burnett, Outl. Bot.: 1153. Jun 1835 [‘Ephemerinae’], nom. illeg.; Cartonemataceae Pichon in Notul. Syst. (Paris) 12: 219. Feb 1946, nom. cons.

Genera/species 37/650–660

Distribution Tropical and subtropical regions, with the largest diversity in Africa, South Asia, Mexico and northern Central America; some species in temperate East Asia, eastern and southern North America and Australia.

Fossils Leaves and fruits have been found in mid-Miocene layers in Kenya and interpreted as Pollia.

Habit Usually bisexual (often monoecious or andromonoecious, rarely polygamomonoecious), usually perennial (rarely annual) herbs. Usually somewhat succulent, sometimes twining, very rarely epiphytic. Bulb rarely present. Nodes swollen.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza absent. Roots fibrous or tuberous. Phellogen absent. Cortex usually without vascular tissue (cortical vascular bundles usually absent; present in Cartonema). Primary vascular tissue as scattered bundles. Central vascular cylinder surrounded by endodermis-like envelope; longitudinal vascular bundles arranged in a typical pattern and connected only at nodes. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels in root, stem and leaves. Vessel elements with scalariform or reticulate (Cartonematoideae), or simple (Commelinoideae) perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals. Nodes? Raphide canals (mucilage canals) consisting of cells with calciumoxalate raphides (usually absent in Cartonematoideae). Silica bodies usually absent (present in some species).

Trichomes Hairs multicellular, usually uniseriate (in Palisota multiseriate, with some cells thin-walled and sometimes branched); tricellular glandular microhairs present in most genera (absent in Cartonematoideae).

Leaves Alternate (usually spiral, sometimes distichous), simple, entire, often linear, with usually convolute (supervolute; sometimes involute, rarely plicate) ptyxis. Stipules absent; leaf sheath closed; ligule absent. Venation parallelodromous; midvein distinct; few primary veins connected to thin secondary and tertiary veins. Stomata tetracytic, hexacytic or paracytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids as longitudinally aggregated rodlets (Strelitzia type). Epidermis thick, sometimes with silica bodies. Mesophyll with mucilaginous idioblasts or mucilaginous canals containing calciumoxalate raphides (absent in Cartonematoideae). Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal and/or axillary, principally cymose paniculate thyrse composed of helicoid partial inflorescences (cincinni), in Cartonematoideae raceme- or spike-like (flowers sometimes solitary), in some species surrounded by large bracts, spathae. Bracts sometimes boat-shaped. Floral prophyll (bracteole) usually median (prophylls in Dichorisandra lateral).

Flowers Actinomorphic or zygomorphic (transversally so i Dichorisandra; asymmetric in, e.g., Cochliostema). Hypogyny. Tepals usually 3+3 (rarely 3+2); outer tepals with imbricate aestivation, usually sepaloid or scale-like (sometimes petaloid), free or connate below; inner tepals with imbricate aestivation, petaloid, thin, often stipitate, usually early caducous, free or connate at base (in some species connate into a tube); when zygomorphic, then usually median inner tepal abaxial. Nectaries usually absent (possibly present on staminodia in species of Commelina). Septal nectaries absent. Disc absent. Enantiostyly present in Murdannia.

Androecium Stamens usually 3+3 (rarely fewer), two or three (rarely four) of which often staminodial (rarely three fertile stamens and no staminodia); some stamens often strongly yellow, showy, attracting and with fewer pollen grains than in remaining stamens. Filaments glabrous or often entirely or partially covered with long and usually moniliform hairs, free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed or dorsifixed, sometimes versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse, latrorse, or extrorse, usually longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits; rarely poricidal, dehiscing by apical pores); connective sometimes slightly prolonged. Tapetum amoeboid-periplasmodial; tapetal cell contents early invading anther cavity. Tapetal cells often with calciumoxalate raphides. Endothecium present. Staminodia absent or alternating with stamens (antesepalous or antepetalous), or inserted on one (anterior or posterior) side of flower, and stamens on opposite side; female flowers with staminodia.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains usually monosulcate (rarely inaperturate or di-, tri- or tetrasulcate), shed as monads, bicellular or tricellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum, verrucate, spinulate or granulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of usually three connate carpels (sometimes two by degeneration of dorsal carpel); median carpel abaxial. Ovary superior, usually bilocular or trilocular (rarely unilocular; sometimes unilocular at apex and trilocular in lower part). Style single, simple, straight or curved, usually narrow. Stigma simple, small or large, punctate, capitate, penicillate, triangular or somewhat trilobate, papillate or non-papillate, Dry or Wet type. Male flowers often with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation usually axile (rarely parietal or basal). Ovules one to c. 20 (to more than 50; in Cartonematoideae two) per carpel, orthotropous, hemianatropous or campylotropous (rarely anatropous), ascending, bitegmic, weakly crassinucellar. Micropyle usually endostomal (sometimes exostomal). Outer integument three to seven (to ten) cell layers thick. Inner integument two cell layers thick. Nucellar cap one or two cell layers thick. Parietal cell usually formed from archesporial cell. Parietal tissue one or two cell layers thick. Periclinal divisions sometimes taking place in megasporangial epidermis (parietal cell not formed). Megagametophyte monosporous, usually Polygonum type (rarely disporous, Allium type, or tetrasporous, Adoxa, Oenothera or Scilla types). Antipodal cells usually early degenerating (in Tinantia persistent). Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustorium chalazal. Embryogenesis asterad.

Fruit A loculicidal capsule, a berry-like capsule or a berry.

Seeds Aril present in some genera. Operculum formed by testa (and combined with micropylar collar). Seed coat usually endotestal-exotegmic. Exotesta thin. Endotestal cells usually with silica bodies. Endotegmen thin. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, starchy; starch grains usually complex. Suspensor absent. Embryo small, straight, situated opposite hilum, usually well differentiated (in Cartonematoideae little differentiated), covered by discoid or conical operculum, embryotega, usually surrounded by a micropylar collar (absent in Cartonema), without chlorophyll (non-photosynthesizing), Xyris-Scirpus type. Cotyledon usually one (sometimes two, one of which rudimentary). Cotyledon hyperphyll elongate (directed downwards) or compact, not assimilating. Hypocotyl internode long, short or absent. Mesocotyl usually absent (present in Cartonema). Coleoptile often present. Collar rhizoids usually present (absent in Cartonema). Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 4, 6, 7, 9–17, 20, 29 (Commelinoideae); n = 12 (Cartonematoideae) – Polyploidy and aneuploidy occurring.

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols, 6-hydroxyluteolin, flavone-C-glycosides, cyanidin-3,7,3’-triglycoside, and phenolic acids present. Alkaloids, steroidal saponins, and tyrosine-derived cyanogenic compounds rare. Ellagic acid and chelidonic acid not found.

Use Ornamental plants, medicinal plants.

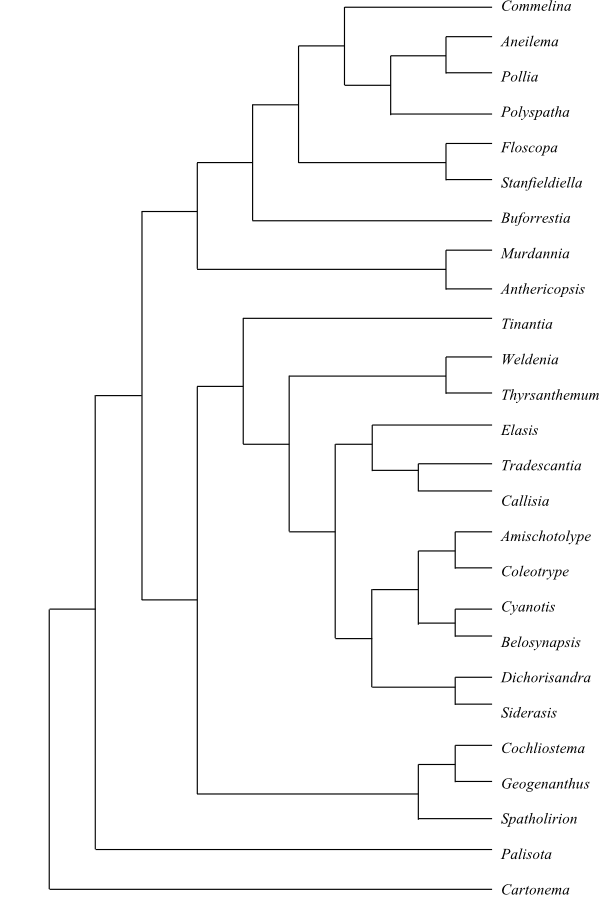

Systematics Commelinaceae are probably sister-group to Hanguanaceae. Cartonema (Australia) and Triceratella (Africa) together form a sister to the remaining Commelinaceae.

Cartonematoideae (Pichon) Faden ex G. C. Tucker in J. Arnold Arbor. 70: 99. 10 Jan 1989

2/12. Cartonema (11; tropical Australia), Triceratella (1; T. drummondii; Zimbabwe). – Cortical vascular bundles present. Stem collenchyma absent. Vessel elements with scalariform or reticulate perforation plates. Silica bodies absent. Raphide canals present adjacent to veins or absent. Stomata paracytic or tetracytic. Microglands absent; normal glandular hairs frequent. Inflorescence racemose or with a single flower per cincinnus. Flowers sessile, yellow. Ovules two per carpel. Fruit a berry. Main part of testa caducous. Operculum without collar. Collar short. Collar rhizoids absent. Mesocotyl present. Radicula stout. n = 12.

Commelinoideae Eaton, Bot. Dict., ed. 4: 27. Apr-Mai 1836 [‘Commelineae’]

35/645–655. Palisota (18); Commelineae Dumort., Anal. Fam. Plant.: 55. 1829. Murdannia (50–55; tropical and subtropical regions on both hemispheres), Anthericopsis (1; A. sepalosa; tropical East Africa), Buforrestia (3; B. candolleana: French Guiana, Suriname; B. mannii, B. obovata: tropical West and Central Africa), Floscopa (c 20; tropical and subtropical regions on both hemispheres), Stanfieldiella (4; S. axillaris, S. brachycarpa, S. imperforata, S. oligantha; tropical Africa), Commelina (c 170; tropical and subtropical regions on both hemispheres), Polyspatha (3; P. hirsuta, P. oligospatha, P. paniculata; tropical West Africa), Aneilema (68; tropical and southern Africa, Madagascar, Yemen, few species in tropical Asia to tropical Australia and islands in southwestern Pacific; one species, A. brasiliense; in tropical South America), Pollia (17; tropical regions in the Old World, tropical Australia; one species, P. americana, in Panamá). – Tradescantieae Meisn., Plant. Vasc. Gen.: Tab. Diagn. 406. 17-20 Aug 1842. Spatholirion (6; S. calcicola, S. decumbens, S. elegans, S. longifolium, S. ornatum, S. puluongense; southern China, Southeast Asia), Cochliostema (2; C. odoratissimum, C. velutinum; Nicaragua to Ecuador), Geogenanthus (3; G. ciliatus, G. poeppigii, G. rhizanthus; tropical South America); Tinantia (13–14; Texas to tropical South America), Thyrsanthemum (3; T. floribundum, T. goldianum, T. macrophyllum; Mexico), Weldenia (1; W. candida; Mexico, Guatemala), Elasis (2; E. hirsuta: Ecuador; E. guatemalensis: Central America), Callisia (c 20; southern United States to Argentina), Tradescantia (c 80; North to South America), Dichorisandra (c 30; Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America), Siderasis (1; S. fuscata; southeastern Brazil), Amischotolype (15; tropical regions in the Old World), Coleotrype (9; tropical and southern Africa, Madagascar), Belosynapsis (6; B. ciliata, B. epiphytica, B. kawakamii, B. kewensis, B. moluccana, B. vivipara; Madagascar, tropical Asia from India to New Guinea), Cyanotis (c 50; tropical and subtropical regions of the Old World, from Africa to northern Australia). – Unplaced Commelinoideae Aetheolirion (1; A. stenolobium; Thailand), Dictyospermum (5; D. conspicuum, D. humile, D. montanum, D. ovalifolium, D. ovatum; India, Sri Lanka to New Guinea), Gibasoides (1; G. laxiflora; Mexico), Matudanthus (1; M. nanus; Mexico), Plowmanianthus (5; P. dressleri, P. grandifolius, P. panamensis, P. perforans, P. peruvianus; Panama, Amazonas), Pseudoparis (3; P. cauliflora, P. monandra, P. tenera; Madagascar), Sauvallea (1; S. blainii; Cuba), Streptolirion (1; S. volubile; eastern Himalayas to Southeast Asia and the Korean Peninsula), Tapheocarpa (1; T. calandrinioides; northeastern Queensland), Tricarpelema (8; tropical Asia; one species, T. africanum, in Cameroon, Gabon and Equatorial Guinea). – Tropical, subtropical, temperate parts of North America and East Asia. Cortical vascular bundles absent. Stem collenchyma present. Vessels present also in stem and leaves. Vessel elements with simple perforation plates. Stem with narrow cortex and endodermis-like envelope surrounding vascular bundles connected to one another only at nodes. Silica bodies sometimes present. Raphide canals present between veins. Stomata tetracytic, hexacytic, and other types. Tricellular microglands present. Petals sometimes connate into a tube. Stamens one to six. Filaments often densely beset with uniseriate hairs. Anthers often procidal. Staminodia often two to four, attracting pollinators. Pollen grains usually with calciumoxalate raphides. Polar nuclei early fusing. Seed operculum (embryotega) testal, with one micropylar collar. Collar roots present. Mesocotyl absent. Cyanidin-3,7,3’-triglucoside present. – Palisota is sister to the remaining Commelinoideae in the study by Evans & al. (2003).

|

Cladogram of Commelinaceae based on DNA sequence data (Evans & al. 2003). |

HAEMODORACEAE R. Br. |

( Back to Commelinales ) |

Xiphidiaceae Dumort., Anal. Fam. Plant.: 59, 61. 1829 [‘Xiphideae’, ‘Xiphidieae’, ‘Xiphineae’]; Haemodorales R. Br. in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp. Regn. Veg.: 9. Sep-Oct 1835 [‘Haemodoraceae’]; Wachendorfiaceae Herb., Amaryllidaceae: 48. late Apr 1837; Dilatridaceae M. Roem., Handb. Allg. Bot. 3: 476. 1840 [’Dilatrideae’]; Conostylidaceae (Benth.) Takht., Sist. Magnoliof. [Systema Magnoliophytorum]: 313. 24 Jun 1987

Genera/species 14/95–105

Distribution South Africa, New Guinea, Australia, Tasmania, eastern and southeastern North America, Central America, northern South America, with their largest diversity in Australia.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, perennial herbs. Tuberous stem (Pyrrorhiza, Tribonanthes) or bulb (Haemodorum) and often stolons. Roots and subterranean stems often intensely red to reddish-brown.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza absent. Phellogen absent. Primary vascular tissue a single cylinder of bundles, or two or several bundle cylinders, or scattered bundles. Stem vascular bundles numerous, collateral to amphivasal, surrounded by a sclerified cylinder. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels at least in root metaxylem (in Lachnanthes also in stem). Vessel elements with simple or scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform or alternate, simple and/or bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids with simple pits. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals. Nodes? Coloured latex present in some representatives. Tanniniferous lignified idioblasts present in Conostylidoideae. Calciumoxalate raphides usually numerous. Styloids? Silica bodies usually absent (often present in Conostylis).

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, narrowing, pilate, uniseriate or branched, usually with multicellular base.

Leaves Alternate (distichous), simple, entire, linear, often ensiform, isobifacial, sometimes subulate (in Tribonanthes tubular), often coriaceous, with conduplicate or plicate ptyxis. Stipules absent; leaf sheath short. Venation parallelodromous. Stomata paracytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids small or non-orientated. Mesophyll in Dilatris with mucilaginous idioblasts usually containing calciumoxalate raphides. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal, usually panicle, thyrsoid, racemoid, head-like or corymb, usually compound, with helicoid partial inflorescences (flowers in Tribonanthes uniflora solitary). Extrafloral nectaries sometimes present.

Flowers Actinomorphic or zygomorphic (sometimes transversally zygomorphic, sometimes split-monosymmetric; in Anigozanthus somewhat oblique), sometimes large. Epigyny, half epigyny or hypogyny (probably secondary). Tepals 3+3, membranous to thick, externally usually with numerous narrowing, pilate or dendritic hairs (sometimes glabrous), usually with imbricate aestivation (posterior outer tepal median), free or connate only at base (tepals in Anigozanthos, Blancoa, Conostylis six in a single whorl, usually with valvate aestivation, connate and tubular); tanniniferous cells? Septal nectaries usually present below insertion point of tepals (absent in Phlebocarya and Xiphidium). Disc absent. Mucilaginous chamber present in flowers of Dilatris. Enantiostyly present in Wachendorfia.

Androecium Stamens three antepetalous (outer staminal whorl absent in most Haemodoroideae; in Pyrrorhiza two staminodia and one fertile stamen; in Schiekia two staminodia and four fertile stamens) or 3+3 (Conostylidoideae). Filaments subulate or flattened, free, often adnate to inner tepals or perianth tube, respectively. Anthers basifixed, subbasifixed or dorsifixed, sometimes versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective sometimes with appendage. Tapetum usually amoeboid-periplasmodial (sometimes secretory). Tapetal cells often with calciumoxalate raphides. Staminodia in Pyrrorhiza and Schiekia two.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains monosulcate (Haemodoroideae) or di- or triporate or hepta- or octoporate (Conostylidoideae), heteropolar, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Pollen grains sometimes without starch. Exine usually two-layered (sometimes one- or three-layered), intectate, without foot layer, verrucate (Haemodoroideae, rarely foveolate) or rugulate (Conostylidoideae).

Gynoecium Pistil composed of usually three connate carpels (in Barberetta only one fertile). Ovary inferior, semi-inferior or superior (probably secondarily), usually trilocular (in Phlebocarya trilocular at base and unilocular at apex; in Barberetta unilocular due to reduction of two carpels). Style single, subulate or flattened, simple or trifid, with stylar canal. Stigma single, round, or stigmas three, papillate, Dry or Wet type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation usually axile (in Phlebocarya basal); placentae swollen. Ovules one to more than 50 per carpel, anatropous (hemianatropous?) or orthotropous, hypotropous or pleurotropous, or irregular, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle usually endostomal (sometimes exostomal). Outer integument usually two cell layers thick. Inner integument usually two cell layers thick. Parietal cell formed from archesporial cell. Nucellar cap sometimes present. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development helobial. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis probably asterad (or onagrad).

Fruit A loculicidal to apically poricidal capsule (in some species indehiscent; in Phlebocarya a nut; in one species of Anigozanthos a schizocarp with three nut-like mericarps).

Seeds Aril absent. Caruncle present in Wachendorfia. Testal cells elongate, more or less thin-walled. Outer exotestal epidermis sometimes with brown or black pigments. Exotesta collapsed in Conostyloideae. Tegmic cells compressed, brown, sometimes elongate. Operculum absent. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, with outer layer of thick-walled pitted cells containing lipids and aleurone, and inner layer of thin-walled unpitted cells containing starch; starch grains usually simple (sometimes compound). Embryo small, present near micropyle, Trillium type, chlorophyll? Cotyledon one. Hypocotyl internode short to long. Mesocotyl? Cotyledon hyperphyll elongate, assimilating, or compact, not assimilating. Coleoptile absent (sometimes with a median lobe of cotyledon sheath). Collar rhizoids? Germination?

Cytology n = 4–8, 11, 14, 16, 21, 28 (Conostylidoideae); n = 12, 15, 19–21, 24 (Haemodoroideae)

DNA 5 bp insertion absent from the plastid gene matK

Phytochemistry O-methylated flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), proanthocyanidins (cyanidin, prodelphinidin), chelidonic acid, phenylphenalenones (perinaphthenones), arylphenalenones, and fructans present. Diferulic acids and p-coumaric acids in cell walls. Ellagic acid, saponins, and cyanogenic compounds not found. Alkaloids?

Use Ornamental plants, medicinal plants.

Systematics Haemodoraceae may be sister-group to Pontederiaceae. There are two distinct main clades in Haemodoraceae (Hopper & al. 2009): Haemodoroideae and Conostylidoideae, the latter endemic in Southwest Australia.

Haemodoroideae Arn., Botany: 133. 9 Mar 1832 [’Haemodoreae’]

8/34. Dilatris (4; D. corymbosa, D. ixioides, D. pillansii, D. viscosa; Western Cape), Haemodorum (20; southwestern, northern and eastern Australia, Tasmania), Lachnanthes (1; L. caroliniana; Nova Scotia and Massachusetts to Louisiana and Florida, Cuba), Barberetta (1; B. aurea; Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal), Wachendorfia (4; W. brachyandra, W. multiflora, W. paniculata, W. thyrsiflora; Western and Eastern Cape), Schiekia (1; S. orinocensis; northern South America, Brazil, Bolivia), Xiphidium (2; X. caeruleum: southern Mexico Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America; X. xanthorrhizon: western Cuba, Isla de la Juventud), Pyrrorhiza (1; P. neblinae; Venezuela). – Tropical, subtropical and warmtemperate regions, southern Africa, in Southeast Asia only West of Wallace’s line, absent from southern South America. Bulb sometimes present. Roots red. Hairs with distinct basal cells. Zygomorphic flowers resupinate (median inner tepal abaxial, median carpel adaxial). Hypogyny (secondary). Perianth sometimes differentiated. Adaxial outer tepal in Wachendorfia and Schiekia adnate at base to the lateral/abaxial outer tepals and the two lateral/adaxial inner tepals. Flowers often enantiostylous. Supralocular septal nectaries present in Dilatris. Stamens usually three (antepetalous; outer staminal whorl usually absent; in Pyrrorhiza a single stamen; staminodia sometimes present). Pollen grains monosulcate. Seeds often flattened, finely hairy or winged. Cotyledon not photosynthesizing. Hypocotyl short or absent. n = 12, 15, 19–21, 24. Tannins absent.

Conostylidoideae Lindl., Veg. Kingd.: 153. Jan-Mai 1846 [‘Conostyleae’]

6/62–70. Tribonanthes (6–7; T. australis, T. brachypetala, T. longipetala, T. minor, T. purpurea, T. violacea; southwestern Western Australia), Phlebocarya (3; P. ciliata, P. filifolia, P. pilosissima; southwestern Western Australia), Blancoa (1; B. canescens; southwestern Western Australia), Conostylis (40–45; southwestern Western Australia), Anigozanthos (11–12; southwestern Western Australia), Macropidia (1; M. fuliginosa; western Western Australia). – Mainly southwestern Australia. Tanniniferous lignified idioblasts present. Silica sand present. Epidermal cell walls sometimes thickened. Hairs branched. Leaf margin sometimes spiny. Inner tepals often connate (in Anigozanthus six tepals connate into a tube). Flowers usually hairy, sometimes pseudomonocyclic, valvate, zygomorphic. Supralocular septal nectaries usually present. Stamens 3+3. Filaments sometimes adnate to inner tepals. Pollen grains 2–3-porate or 7–8-porate. Placentae with tanniniferous cells. Fruit sometimes a schizocarp or indehiscent. Seeds sometimes ridged. Cotyledon photosynthesizing. Hypocotyl present. Radicula well developed. n = 4–8, 11, 14, 16, 21, 28.

|

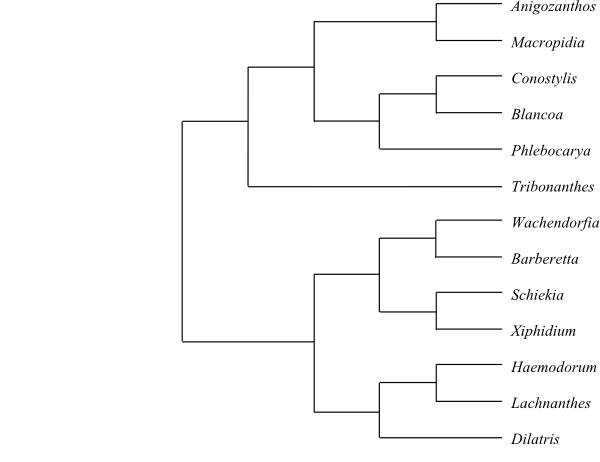

Cladogram of Haemodoraceae based on DNA sequence data (Hopper & al. 2009). |

HANGUANACEAE Airy Shaw |

( Back to Commelinales ) |

Hanguanales R. Dahlgren ex Reveal in Novon 2: 239. 13 Oct 1992

Genera/species 1/12

Distribution Sri Lanka, Indochina, Malesia to Palau and northern Australia.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Dioecious, perennial herbs. Helophytes.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen absent. Stem cortex thin, with scattered vascular bundles. Endodermis distinct. Central tissue of stem starchy and with fibrous vascular bundles. Primary vascular tissue as scattered closed bundles. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels present in roots. Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements probably tracheids. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals. Nodes? Tanniniferous idioblasts and mucilage canals present. Silica bodies present. Raphides rare.

Trichomes Hairs multicellular, branched, with sunken uniseriate base (frequent especially on younger individuals).

Leaves Alternate (spiral), simple, entire, sometimes linear, with supervolute ptyxis, differentiated into pseudopetiole and pseudolamina. Stipules absent; leaf sheath open. Venation pinnate-parallelodromous, tessellate, with distinct midvein and numerous transversal secondary veins. Stomata tetracytic. Cuticular waxes absent. Silica bodies present in endodermis, abaxial hypodermis and mesophyll in some species. Epidermis without silica bodies. Mesophyll with tanniniferous idioblasts. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal, panicle with spike-like partial inflorescences consisting of few-flowered monochasia. Floral prophyll (bracteole) absent.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Pedicel absent. Hypogyny. Tepals 3+3, pseudomonocyclic, sepaloid, bract-like, persistent, connate at base. Septal (gynoecial) nectary tripartite, present in male flowers; basal-adaxial staminodial nectaries present in female flowers. Disc absent (male floral receptacle terminating in an accumulation of fleshy structures).

Androecium Stamens 3+3. Filaments filiform, wider at base, almost free (connate at base), adnate to tepals at base. Anthers basifixed to subbasifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum amoeboid-periplasmodial. Female flowers with 3+3 reduced staminodia, three inner ones nectar-secreting (nectaries).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains inaperturate, shed as monads, ?-cellular at dispersal. Pollen grains without starch. Exine tectate, with columellate? infratectum, spinulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of three connate carpels. Ovary superior, unilocular above and trilocular below, with mucilaginous hairs on inner side. Style single, simple, very short and wide, or absent. Stigma deeply trilobate, type? Male flowers with reduced pistillodium consisting of three stigmatic lobes and three basal nectaries.

Ovules Placentation basal-axile. Ovule one per carpel, orthotropous to hemianatropous, pendulous, bitegmic, tenuinucellar. Micropyle ?-stomal. Outer integument ? cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Obturator funicular. Epidermal cells anticlinally elongate. Parietal cell not formed (parietal tissue absent). Suprachalazal zone massive. Megagametophyte? Endosperm development nuclear? Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A one-seeded (to three-seeded) berry (berry-like drupe?).

Seeds Aril absent. Seed enclosing placenta during development. Seed coat testal(-tegmic). Testa approx. five cell layers thick. Mesotesta sclerified. Endotesta sclerified, with thickened inner periclinal cell walls. Tegmen collapsing and degenerating, with two layers of crossing fibres. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, starchy, surrounded by a layer of aleurone-rich cells. Embryo small, well differentiated, without chlorophyll. Cotyledon one, compact, not photosynthesizing. Hypocotyl internode? Cotyledon hyperphyll? Coleoptile? Collar rhizoids? Radicula well developed. Germination? First leaf of seedling a cataphyll.

Cytology n = c. 24, 36, ≥45 – Chromosomes very small (less than 1 µm).

DNA 5 bp insertion present in the plastid gene matK

Phytochemistry Insufficiently known. Cyanidin and proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins) present. Ferulic acid present in cell walls. Flavonols not found.

Use Medicinal plants.

Systematics Hanguana (12; Sri Lanka, Indochina, Malesia to Palau and tropical Australia).

Hanguana is probably sister to Commelinaceae.

PHILYDRACEAE Link |

( Back to Commelinales ) |

Philydrales Dumort., Anal. Fam. Plant.: 62. 1829 [‘Phylidrarieae’]

Genera/species 3/5

Distribution India, the Andaman Islands, East and Southeast Asia to New Guinea, southwestern, northern and eastern Australia, Guam, with their highest diversity in Australia.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, perennial herbs. Philydrella has a starch-storing corm. Roots fibrous.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen absent. Stem cortex and stem centre in Philydrum with vascular bundles and in between with lignified sclerenchymatous tissue containing small collateral or semiconcentric bundles. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels present in root (and sometimes stem) metaxylem. Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids, simple pits? Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals. Nodes? Tanniniferous cells frequent. Laticifers absent. Idioblasts with calciumoxalate styloids abundant. Silica bodies absent.

Trichomes Hairs multicellular, uniseriate, with long terminal cell, densely spaced and woolly; glandular hairs small, sunken.

Leaves Alternate (usually spiral, lower leaves usually distichous), usually isobifacial-equitant (ensiform) with margin facing stem (not in Philydrella), simple, entire, usually linear (in Philydrella subulate), with conduplicate ptyxis. Stipules and ligule absent; leaf sheath short, open. Venation parallelodromous, with numerous primary veins connected to transversal secondary veins. Stomata paracytic (sometimes almost tetracytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids? Mesophyll with cells containing calciumoxalate raphides. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal, simple or compound spike in axil of spathe-like bract, sometimes partially adnate to flowers.

Flowers Zygomorphic. Hypogyny or almost hypogyny. Tepals 2(–3)+2(–3), petaloid, usually partially connate (rarely free; all tepals in Helmholtzia connate in lower part); median outer tepal larger than two lateral inner tepals (in Philydrum two inner tepals very small); two lateral outer tepals and median adaxial inner tepal connate into an upper lip; median abaxial outer tepal forming a lower lip; two lateral inner tepals small and usually free (in Philydrella adnate to stamen); tanniniferous cells? Nectaries present in some representatives. Septal nectaries absent. Disc absent. Enantiostyly present.

Androecium Stamen single (probably corresponding to median abaxial inner stamen). Filament wide, flattened, usually free from (sometimes adnate to) median abaxial inner tepal. Anther basifixed to dorsifixed, versatile, peltate, tetrasporangiate, usually introrse to latrorse (in Philydrella curved and hence extrorse; in Philydrum spirally twisted), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Placentoid present. Tapetum secretory, with uninucleate to quadrinucleate cells. Tapetal cells often with calciumoxalate raphides. Staminodia usually absent (in Philydrum rarely a small lateral staminodium from outer staminal whorl).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains monosulcate, trisulcate, monosulculate, trisulculate or zonoaperturate, shed as monads, tetrads (Philydrum) or polyads, bicellular at dispersal, with calciumoxalate raphides. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, reticulate or microreticulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of three connate carpels; median carpel abaxial, often smaller than lateral carpels. Ovary superior or almost so, trilocular, or unilocular in upper part and trilocular in lower part (Philydrum). Style single, simple. Stigma large, usually capitate (sometimes trilobate), papillate, Dry type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation usually axile (when ovary trilocular; in Philydrum intrusively parietal and ovary unilocular in upper part). Ovules c. 15 to more than 100 per ovary (Philydrum) or c. 15 to c. 50 per carpel (Philydrella, Helmholtzia), anatropous, apotropous or epitropous, pleurotropous, bitegmic, weakly crassinucellar. Micropyle ?-stomal. Outer integument one or two cell layers thick. Inner integument two or three cell layers thick. Obturator funicular. Hypostase present. Parietal cell formed from archesporial cell; parietal tissue sometimes two cell layers thick. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development helobial of an aberrant type: small chalazal endosperm chamber with rapid cell division as compared to large micropylar chamber, which develops into nutrient tissue. Endosperm haustorium chalazal. Embryogenesis variation of onagrad.

Fruit Usually a loculicidal capsule (rarely irregularly dehiscent; fruit in Helmholtzia berry-like, leathery).

Seeds Aril absent. Seed sometimes with chalazal hood-shaped structure. Exotestal outer epidermis at micropylar end forming caruncle-like prolongation formed from outer integument. Exotestal cells thick-walled. Endotesta? Exotegmen? Endotegmen tanniniferous. Operculum formed from tegmen (and combined with micropylar collar?). Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, proteinaceous, oily and starchy, and with crystalline aleurone bodies; starch grains large elliptic to bean-shaped, and small isodiametric, respectively. Suspensor almost undeveloped. Embryo straight, well differentiated, Trillium type, with chlorophyll. Cotyledon one, linear, photosynthesizing, dorsiventrally flattened (bifacial). Cotyledon hyperphyll prolonged, assimilating. Hypocotyl internode absent. Coleoptile absent. Collar rhizoids present. Radicula very short. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 8, 16, 17

DNA

Phytochemistry O-methylated flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, syringetin), cyanidin, delphinidin, and proanthocyanidins present. Ferulic and diferulic acids present in cell walls. Ellagic acid, alkaloids, saponins, and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Ornamental plants.

Systematics Helmholtzia (2; H. glaberrima: southeastern Queensland, northeastern New South Wales; H. acorifolia: New Guinea, northestern Queensland), Philydrum (1; P. lanuginosum; India, the Andaman Islands, southern China, Japan, Taiwan, Burma, Thailand, Vietnam, Malesia to New Guinea, northern and eastern Australia to Victoria, Guam), Philydrella (2; P. drummondii, P. pygmaea; southwestern Western Australia).

Philydraceae are probably sister to [Haemodoraceae+Pontederiaceae].

Philydrella is sister to the [Philydrum+Helmholtzia] clade, according to Saarela & al. (2008).

PONTEDERIACEAE Kunth |

( Back to Commelinales ) |

Pontederiales A. Rich. in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp. Regn. Veg.: 7. Sep-Oct 1835 [‘Pontederaceae’]; Unisemataceae Raf., New Fl. N. Amer. 2: 75. Jul-Dec 1837 [’Unisemides’], nom. illeg.; Heterantheraceae J. Agardh, Theoria Syst. Plant.: 36. Apr-Sep 1858 [’Heteranthereae’]; Pontederianae Takht. ex Reveal in Novon 2: 236. 13 Oct 1992

Genera/species 5/31

Distribution Pantropical, with their largest diversity in tropical America, some species in subtropical and warm-temperate regions on both hemispheres.

Fossils A fossilized shoot with roots, which is similar to extant Monochoria or ‘Eichhornia’, was described from the Maastrichtian Deccan Intertrappean Beds in India. Pontederites, which may be assigned to Pontederiaceae, has been found in Eocene layers in the United States, and seeds and leaves of Pontederiaceae occur in Cenozoic layers.

Habit Bisexual, usually perennial (sometimes annual) herbs. Aquatic (sometimes freely floating) or helophytes. Vegetative stems with indeterminate growth.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen absent. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels in root (in some species ‘Eichhornia’ and Heteranthera also in stem). Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids with simple? pits. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals. Nodes? Idioblasts (myriophyllin cells) with condensed tannins present in some species. Laticifers absent. Calciumoxalate raphides present, in Pontederia also cells with styloids or one or two prismatic crystals. Tanniniferous cells (idioblasts) sometimes present in pseudopetioles. Silica bodies absent.

Trichomes Hairs usually absent; glandular hairs absent.

Leaves Alternate (usually distichous, sometimes spiral; rarely verticillate), simple, entire, linear or differentiated into pseudopetiole and pseudolamina (pseudopetiole in ‘Eichhornia’ swollen and air-filled); pseudolamina of younger leaves often enclosing pseudopetiole of older leaves (leaves in Hydrothrix strongly reduced, filiform), with ? ptyxis. Stipules absent; leaf sheath short, open or closed, often as an axillary or median ochrea-like structure, large and enclosing stem, or reduced to a ligule or absent. Colleters present. Venation parallelodromous with converging veins or pinnate-parallel, acrodromous; primary veins longitudinal and connected to transversal secondary veins. Stomata paracytic; adjacent cells with oblique divisions. Cuticular wax crystalloids absent. Mesophyll with calciumoxalate raphides or single prismatic crystals. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal, panicle, thyrse, raceme-, spike- or umbel-like, subtended by two basal foliaceous or sheathing bracts, upper one often a spatha (flowers sometimes solitary; in Hydrothrix enantiomery: two flowers in each pair mirror images, densely inserted inside a spatha and forming a pseudanthium).

Flowers Zygomorphic (sometimes almost actinomorphic; sometimes obliquely zygomorphic), sometimes large. Hypogyny. Tepals usually 3+3 (sometimes three or 2+2), pseudomonocyclic, petaloid (outer tepals in Monochoria almost sepaloid), usually early caducous, more or less connate at base into a tube. Septal nectaries present in ‘Eichhornia’ and Pontederia. Triheterostyly and pollen trimorphism present in species of Pontederia and ‘Eichhornia’; (somatic) enantiostyly with left-hand and right-hand oriented flowers and staminal dimorphism present in Monochoria and Heteranthera.

Androecium Stamens usually 3+3 (sometimes 2+2, three or one, by reduction of outer staminal whorl). Filaments glandular hairy or with moniliform hairs, free, adnate to tepals. Anthers basifixed (sometimes auriculate and seemingly dorsifixed), sometimes versatile?, tetrasporangiate, introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits) or poricidal (dehiscing by apical pores). Tapetum amoeboid-periplasmodial or secretory, with ab initio uninucleate or binucleate cells. Staminodia usually absent (sometimes two or three, when fertile stamens fewer than six).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains usually disulculate (rarely monosulculate or trisulculate), shed as monads, bicellular or tricellular at dispersal. Exine intectate, acolumellate, with pollen surface verrucate, scabrate or finely reticulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of three connate carpels (in Pontederia pseudomonomerous, with only median carpel developing and fertile). Ovary superior, unilocular (sometimes due to reduction of two carpels) or trilocular. Style single, simple, glabrous or hairy. Stigma small, capitate or trilobate, papillate, Dry type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation usually axile (when ovary unilocular, then seemingly parietal, with intrusive placentae). Ovules one per ovary or usually ten to more than 50 per carpel, anatropous, pendulous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle bistomal. Outer integument two cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Parietal cell formed from archesporial cell but usually not forming a parietal tissue (parietal tissue in Monochoria one cell layer thick). Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Synergids with a filiform apparatus. Endosperm development helobial (cell wall formation starting much earlier in small chalazal chamber than in large micropylar chamber). Endosperm haustoria at least in Monochoria two micropylar, developing from each side of chalazal chamber and protruding into chalazal tissue, micropylar chamber subsequently fusing with haustoria. Embryogenesis asterad.

Fruit Usually a loculicidal or irregularly dehiscent capsule (in Pontederia an achene, surrounded by hardening persistent petiole bases, forming an anthocarp).

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat testal. Exotestal cells longitudinally elongate, box-shaped. Endotestal cells thin, transversally elongate, with prolonged end-walls, with silica crystals? Tegmen crushed, containing a reddish-brown pigment. Operculum present (combined with the micropylar collar?). Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, starchy, with simple starch grains. Suspensor little or not developed. Embryo large, straight, well differentiated, Trillium type, chlorophyll? Cotyledon one, linear, bifacial. Hypocotyl internode absent. Cotyledon hyperphyll elongate, assimilating. Coleoptile absent (tubular cotyledon ligule present). Collar rhizoids present. Plumule lateral. Germination phanerocotylar? First leaves of seedling linear.

Cytology n = (7) 8 (9, 13–17, 20, 21, 24, 26, 29, 30, 36, 37, 40, 41) – Polyploidy and aneuploidy occurring.

DNA 5 bp insertion often present in the plastid gene matK

Phytochemistry O-methylated flavonols, cyanidin, proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins), alkaloids, cyanogenic compounds, phenylphenalenones, arylphenalenones, and polyamines present. Diferulic and p-coumaric acids in cell walls? Ellagic acid chelidonic acid, and saponins not found.

Use Ornamental plants, aquarium plants, vegetables, forage plants.

Systematics ‘Eichhornia’ (7; E. azurea, E. crassipes, E. diversifolia, E. heterosperma, E. natans, E. paniculata, E. paradoxa; southeastern United States?, Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America; incl. Heteranthera, Monochoria and Pontederia etc?), Monochoria (6; M. africana, M. cyanea, M. elata, M. hastata, M. korsakowii, M. vaginalis; northeastern Africa to Japan and Austrtalia; in Eichhornia?), Pontederia (6; P. rotundifolia, P. sagittata, P. subovata, P. triflora, P. angustifolia; Canada to Argentina; in Eichhornia?), Heteranthera (9; tropical and subtropical Africa and America; in Eichhornia), Hydrothrix (1; H. gardneri; northeastern Brazil; in Eichhornia?), Eurystemon (1; E. mexicanum; Mexico, northern Central America; in Eichhornia?), Scholleropsis (1; S. lutea; Lake Chad in northern Cameroon, Madagascar; in Eichhornia?).

Pontederiaceae are probably sister-group to Haemodoraceae.

Generic delimitations are unclear. ’Eichhornia’ is paraphyletic and should either include the entire Pontederiaceae or be split. Zosterella is included in Heteranthera.

In Heteranthera, Eichhornia s. str. and Pontederia s. str. the leaves of the axillary shoot entirely enclose the main stem in bud, or the pseudolamina of the young leaf completely enclose the pseudopetiole of the second oldest leaf. This may be a synapomorphy.

|

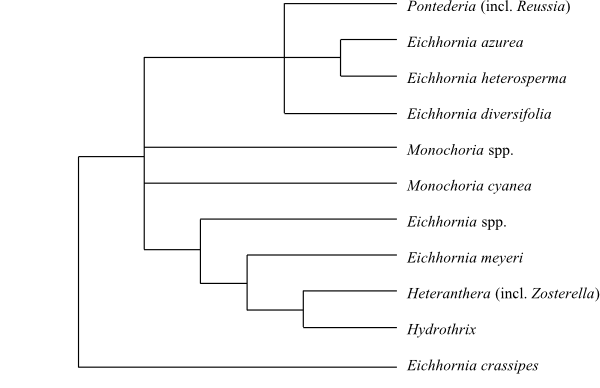

Cladogram (simplified) of Pontederiaceae based on DNA sequence data (Kohn & al. 1996). Eichhornia meyeri was identified as sister-group to the remaining Pontederiaceae in the analysis by Ness & al. (2011). |

Literature

Adams LG. 1987. Philydraceae. – In: George AS (ed), Flora of Australia 45, Australian Government Publ. Service, Canberra, pp. 40-46, 454.

Aerne-Hains L, Simpson MG. 2017. Vegetative anatomy of the Haemodoraceae and its phylogenetic significance. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 178: 117-156.

Airy Shaw HK. 1979. Three interesting plants from the Northern Territory of Australia (Thymelaeaceae, Flacourtiaceae and Hanguanaceae). – Kew Bull. 33: 1-5.

Airy Shaw HK. 1981. A new species of Hanguana from Borneo. – Kew Bull. 35: 819-821.

Anderberg AA, Eldenäs P. 1991. A cladistic analysis of Anigozanthos and Macropidia (Haemodoraceae). – Aust. J. Bot. 4: 655-664.

Anderson E, Woodson RE. 1935. The species of Tradescantia indigenous to the United States. – Contr. Arnold Arbor. Harvard Univ. 9: 1-132.

Aston HI. 1987. Pontederiaceae. – In: George AS (ed), Flora of Australia 45, Australian Government Publ. Service, Canberra, pp. 46-55.

Backer CA. 1951. Flagellariaceae. – In: Steenis CGGJ van (ed), Flora Malesiana I, 4(3), Noordhoff-Kolff N. V., Batavia, pp. 245-250.

Banerji I, Haldar S. 1942. A contribution to the morphology and cytology of Monochoria hastaefolia Presl. – Proc. Indian Acad. Sci., Sect. B, 16: 91-106.

Barker NP, Faden RB, Brink E, Dold AP. 2001. Notes on African plants. Commelinaceae. Rediscovery of Triceratella drummondii, and comments on its relationships and position within the family. – Bothalia 31: 37-39.

Barrett RL, Hopper SD, MacFarlane TD, Barrett MD. 2015. Seven new species of Haemodorum (Haemodoraceae) from the Kimberley region of Western Australia. – Nuytsia 26: 111-125.

Barrett SCH. 1977. The breeding system of Pontederia rotundifolia, a tristylous species. – New Phytol. 78: 209-220.

Barrett SCH. 1978. Floral biology of Eichhornia azurea (Swartz) Kunth (Pontederiaceae). – Aquatic Bot. 5: 217-228.

Barrett SCH. 1979. The evolutionary breakdown of tristyly in Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms (water hyacinth). – Evolution 33: 499-510.

Barrett SCH. 1980. Sexual reproduction in Eichhornia crassipes (water hyacinth) II. Seed production in natural populations. – J. Appl. Ecol. 17:113-124.

Barrett SCH. 1985. Floral trimorphism and monomorphism in continental and island populations of Eichhornia paniculata (Sprengl.) Solms (Pontederiaceae). – Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 25: 41-60.

Barrett SCH. 1988. Evolution of breeding systems in Eichhornia: a review. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 75: 741-760.

Barrett SCH, Anderson JM. 1985. Variation in expression of trimorphic incompatibility in Pontederia cordata L. (Pontederiaceae). – Theor. Appl. Gen. 70: 355-362.

Barrett SCH, Graham SW. 1997. Adaptive radiation in the aquatic plant family Pontederiaceae: insights from phylogenetic analyses. – In: Givnish TJ, Sytsma KJ (eds), Molecular evolution and adaptive radiation, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 225-238.

Barrett SCH, Harder LD. 1992. Floral variation in Eichhornia paniculata (Spreng.) Solms II: effects of development and environment on the formation of selfing flowers. – J. Evol. Biol. 5: 83-107.

Barrett SCH, Husband BC. 1990. Variation in outcrossing rates in Eichhornia paniculata: the role of demographic and reproductive factors. – Plant Spec. Biol. 5: 41-55.

Barrett SCH, Price SD, Shore JS. 1983. Male fertility and anisoplethic population structure in tristylous Pontederia cordata (Pontederiaceae). – Evolution 37: 745-759.

Barrett SCH, Morgan MT, Husband B. 1989. The dissolution of a complex genetic polymorphism: the evolution of self-fertilization in tristylous Eichhornia paniculata (Pontederiaceae). – Evolution 43: 1398-1416.

Bayer C, Appel O, Rudall PJ. 1998. Hanguanaceae. – In: Kubitzki K (ed), The families and genera of vascular plants IV. Flowering plants. Monocotyledons. Alismatanae and Commelinanae (except Gramineae), Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 223-225.

Bazan AC, Edwards JM. 1976. Phenalenone pigments of the flowers of Lachnanthes tinctoria. – Phytochemistry 15: 1413-1415.

Bick IRC, Blackman AJ. 1973. Haemodorin – phenalenone pigment. – Aust. J. Chem. 26: 1377-1380.

Bohm BA, Collins FW. 1975. Flavonoids of Philydrum lanuginosum. – Phytochemistry 14: 315-316.

Brenan JPM. 1952. Notes on African Commelinaceae. – Kew Bull. 7: 179-208.

Brenan JPM. 1960. Notes on African Commelinaceae II. The genus Buforrestia C. B. Cl. and a new related genus, Stanfieldiella Brenan. – Kew Bull. 14: 280-286.

Brenan JPM. 1961. Triceratella, a new genus of Commelinaceae from southern Rhodesia. – Kirkia 1: 14-19.

Brenan JPM. 1964. Notes on African Commelinaceae IV. Ballya, a new genus from East Africa. – Kew Bull. 19: 63-68.

Brenan JPM. 1966. The classification of Commelinaceae. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 59: 349-370.

Brenan JPM. 1984. Two new species of Palisota (Commelinaceae) from West Africa. – Kew Bull. 39: 829-832.

Brückner G. 1926. Beiträge zur Anatomie, Morphologie und Systematik der Commelinaceae. – Engl. Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 61, Beibl. 137: 1-70.

Brückner G. 1930. Commelinaceae. – In: Engler A (ed), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien, 2. Aufl., Bd. 15a, W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 159-181.

Buchmann SL. 1980. Preliminary anthecological observations on Xiphidium caeruleum Aubl. (Monocotyledonae: Haemodoraceae) in Panama. – J. Kansas Entomol. Soc. 53: 685-699.

Burns JH, Munguia P, Nomann BE, Braun SJ, Terhorst CP, Miller TE. 2008. Vegetative morphology and trait correlations in 54 species of Commelinaceae. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 158: 257-268.

Burns JH, Faden RB, Steppan SJ. 2011. Phylogenetic swtudies in the Commelinaceae subfamily Commelinoideae inferred from nuclear ribosomal and chloroplast DNA squences. – Syst. Bot. 36: 268-276.

Cabezas FJ, Estrella M de la, Aedo C, Velayos M. 2009. Checklist of Commelinaceae of Equatorial Guinea (Annobón, Bioko and Río Muni). – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 159: 106-122.

Calderon AI, Chung KS, Gupta MP. 2009. Ecdysteroids from Dichorisandra hexandra (Commelinaceae). – Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 37: 693-695.

Carlquist SJ. 2005. Origins and nature of vessels in monocotyledons 7. Haemodoraceae and Philydraceae. – J. Torrey Bot. Soc. 132: 377-383.

Caro H. 1903. Beiträge zur Anatomie der Commelinaceen. – Ph.D. diss., Universität Heidelberg, Germany.

Cheadle VI. 1968. Vessels in Haemodorales. – Phytomorphology 18: 412-420.

Cheadle VI. 1970. Vessels in Pontederiaceae, Ruscaceae, Smilacaceae, and Trilliaceae. – In: Robson NKB, Cutler DF, Gregory M (eds), New research in plant anatomy, Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 63 [Suppl. 1]: 45-50.

Cheadle VI, Kosakai H. 1980. Occurrence and specialization of vessels in Commelinales. – Phytomorphology 30: 98-117.

Chikkannaiah PS. 1962. Morphological and embryological studies in the Commelinaceae. – In: Plant embryology – A symposium, C.S.I.R., New Delhi, pp. 23-26.

Chikkannaiah PS. 1963. Embryology of some member of the family Commelinaceae: Commelina subulata Roth. – Phytomorphology 13: 174-184.

Coker WC. 1907. The development of the seed in the Pontederiaceae. – Bot. Gaz. 44: 293-301.

Conran JG. 1994. Tapheocarpa (Commelinaceae), a new Australian genus with hypogeous fruits. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 7: 585-589.

Cook CDK. 1989. Taxonomic revision of Monochoria (Pontederiaceae). – In: Kit Tan (ed), The Davis and Hedge Festschrift, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, pp. 149-184.

Cook CDK. 1998. Pontederiaceae. – In: Kubitzki K (ed), The families and genera of vascular plants IV. Flowering plants. Monocotyledons. Alismatanae and Commelinanae (except Gramineae), Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 395-403.

Cooke RG. 1970. Phenylnaphthalene pigments of Lachnanthes tinctoria. – Phytochemistry 9: 1103-1106.

Cooke RG, Dagley IJ. 1979. Coloring matters of Australian plants 21. Naphthoxanthenones in the Haemodoraceae. – Aust. J. Chem. 32: 1841-1847.

Cooke RG, Edwards JM. 1981. Naturally occurring phenalenones and related compounds. – Progr. Chem. Org. Nat. Prod. 40: 153-190.

Cooke RG, Segal W. 1955a. Colouring matters of Australian plants VI. Haemocorin – a unique glycoside from Haemodorum corymbosum Vahl. – Aust. J. Chem. 8: 107-113.

Cooke RG, Segal W. 1955b. Colouring matters of Australian plants V. Haemocorin – the chemistry of the aglycone. – Aust. J. Chem. 8: 413-421.

Cooke RG, Thomas RL. 1975. Colouring matters of Australian plants XVIII. Constituents of Anigozanthos rufus. – Aust. J. Chem. 28: 1053-1057.

Cremona TL, Edwards JM. 1974. Xiphidone, the major phenalenone pigment of Xiphidium caeruleum. – Lloydia 37: 112-113.

Cristobal de Hinojo ME, González L, Frias de Fernández AM. 1998. Estudios citogenéticos en el género Commelina L. (Commelinaceae I. Análisis cariotípico de Commelina erecta L. y Commelina diffusa Burm. – Lilloa 39: 157-164.

Cruzan MB, Barrett SCH. 1993. Contribution of cryptic self-incompatibility to the mating system of Eichhornia paniculata (Pontederiaceae). – Evolution 47: 925-934.

Daumann E. 1965. Das Blütennektarium bei den Pontederiaceen und die systematische Stellung dieser Familie. – Preslia 37: 407-412.

Della Greca M, Molinaro A, Monaco P, Previtera L. 1993. Degraded phenalene metabolites in Eichhornia crassipes. – Nat. Prod. Lett. 1: 233-238.

Dellert R. 1933. Zur systematischen Stellung von Wachendorfia. – Österr. Bot. Zeitschr. 82: 335-345.

Dias DA, Goble DJ, Silva CA, Urban S. 2009. Phenylphenalenones from the Australian plant Haemodorum simplex. – J. Nat. Prod. 72: 1075-1080.

Dora G, Xiang-Qun X, Edwards JM. 1993. Two novel phenylphenalenones from Dilatris viscosa. – J. Nat. Prod. 56: 2029-2033.

Dutt BSM. 1970. Comparative embryology of angiosperms: Haemodoraceae. – Bull. Indian Acad. Natl. Sci., Sect. B, 41: 358-361.

Eckenwalder JE, Barrett SCH. 1986. Phylogenetic systematics of Pontederiaceae. – Syst. Bot. 11: 373-391.

Edwards JM. 1974. Phenylphenalenones from Wachendorfia species. – Phytochemistry 13: 290-291.

Edwards JM, Weiss U. 1970. Perinaphthenone pigments from fruit capsules of Lachnanthes tinctoria. – Phytochemistry 9: 1653-1657.

Edwards JM, Weiss U. 1974. Phenalenone pigments of the root system of Lachnanthes tinctoria. – Phytochemistry 13: 1597-1602.

Engler A. 1888. Philydraceae. – In: Engler A, Prantl K (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien II(4), W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 75-76.

Evans TM. 1995. A phylogenetic analysis of the Commelinaceae based on morphological and molecular data. – Ph.D. diss., University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin.

Evans TM, Faden RB, Sytsma KJ. 2000. Homoplasy in the Commelinaceae: a comparison of different classes of morphological characters. – In: Wilson KL, Morrison DA (eds), Monocots: systematics and evolution, CSIRO, Melbourne, pp. 557-566.

Evans TM, Faden RB, Simpson MG, Sytsma KJ. 2000. Phylogenetic relationships in the Commelinaceae I. A cladistic analysis of morphological data. – Syst. Bot. 25: 668-691.

Evans TM, Sytsma KJ, Faden RB, Givnish TJ. 2003. Phylogenetic relationships in the Commelinaceae II. A cladistic analysis of rbcL sequences and morphology. – Syst. Bot. 28: 270-292.

Faden RB. 1975. A biosystematic study of the genus Aneilema R. Br. (Commelinaceae). – Ph.D. diss., Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri.

Faden RB. 1977. The genus Rhopalephora Haask. (Commelinaceae). – Phytologia 37: 479-481.

Faden RB. 1980. The taxonomy and nomenclature of some Asiatic species of Murdannia (Commelinaceae): the identity of Commelina medica Lour. and Commelina tuberosa Lour. – Taxon 29: 71-83.

Faden RB. 1983a. Phytogeography of African Commelinaceae. – Bothalia 14: 553-557.

Faden RB. 1983b. Isolating mechanisms among five sympatric species of Aneilema R. Br. (Commelinaceae) in Kenya. – Bothalia 14: 907-1002.

Faden RB. 1988a. Vegetative and reproductive features of forest and nonforest genera of African Commelinaceae. – Monogr. Syst. Bot. Missouri bot. Gard. 25: 521-526.

Faden RB. 1991. The morphology and taxonomy of Aneilema R. Brown (Commelinaceae). – Smithsonian Contr. Bot. 76: 1-166.

Faden RB. 1992. Floral attraction and floral hairs in the Commelinaceae. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 79: 46-52.

Faden RB. 1993. Murdannia cryptantha (Commelinaceae), a new species with cleistogamous flowers from Australia and Papua New Guinea. – Novon 3: 133-136.

Faden RB. 1995. Palisota flagelliflora (Commelinaceae), a new species from Cameroon with a unique habit. – Novon 5: 246-251.

Faden RB. 1998. Commelinaceae. – In: Kubitzki K (ed), The families and genera of vascular plants IV. Flowering plants. Monocotyledons. Alismatanae and Commelinanae (except Gramineae), Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 109-128.

Faden RB. 2000. Floral biology of Commelinaceae. – In: Wilson KL, Morrison DA (eds), Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Comparative Biology of the Monocots, CSIRO Publ., Melbourne, pp. 109-128.

Faden RB. 2001. The Commelinaceae of Northeast Tropical Africa (Eritrea, Ethiopia, Djibouti, Somalia and Kenya): diversity and phytogeography. – In: Friis I, Ryding O (eds), Biodiversity research in the Horn of Africa region. Proceedings of the Third International Symposium on the Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea at the Carlsberg Academy, Copenhagen, August 25-27, 1999, Biol. Skr. 54: 213-231.

Faden RB. 2008. Commelina mascarenica (Commelinaceae): an overlooked Malagasy species in Africa. – Adansonia, sér. III, 30: 47-55.

Faden RB, Evans TM. 1999. Reproductive characters, habitat and phylogeny in African Commelinaceae. – In: Timberlake J, Kativu S (eds), African plants. Biodiversity, taxonomy and uses, Proceedings of the 1997 AETFAT Congress, Harare, Zimbabwe, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, pp. 23-38.

Faden RB, Hunt DR. 1987. Reunion of Phaeosphaerion and Commelinopsis with Commelina (Commelinaceae). – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 74: 121-122.

Faden RB, Hunt DR. 1991. The classification of the Commelinaceae. – Taxon 40: 19-31.

Faden RB, Inman KE. 1996. Leaf anatomy of the African genera of Commelinaceae: Anthericopsis and Murdannia. – In: Maesen LJG van der, Burgt XM van der, Madenbach de Rooy JM van (eds), Proceedings of the XIVth AETFAT Congress, 22-27 August, 1994, Wageningen, The Netherlands, Kluwer Academic Publ., London, pp. 464-471.

Faden RB, Suda Y. 1980. Cytotaxonomy of Commelinaceae: chromosome numbers of some African and Asiatic species. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 81: 301-325.

Fenster CB, Barrett SCH. 1994. Inheritance of mating-system modifier genes in Eichhornia paniculata (Pontederiaceae). – Heredity 77: 433-445.

Forman LL. 1962. Aëtheolirion, a new genus of Commelinaceae from Thailand, with notes on allied genera. – Kew Bull. 16: 209-221.

Fourcroy M. 1956. Nouvel exemple de racine bistélique: Tradescantia virginiana. – Bull. Soc. Bot. France 103: 590-595.

Gale RMO, Owens SJ. 1983. The occurrence of an epicuticular layer on the abaxial surface of petals in Tradescantia species (Commelinaceae). – Kew Bull. 37: 515-519.

Geerinck D. 1968. Considérations taxonomique au sujet des Haemodoraceae et des Hypoxidaceae (Monocotylédones). – Bull. Soc. Bot. Belg. 101: 265-278.

Geerinck D. 1969a. Génera des Haemodoraceae et des Hypoxidaceae. – Bull. Jard. Bot. Natl. Belg. 39: 47-82.

Geerinck D. 1969b. Le genre Conostylis R. Br. (Haemodoraceae d’Australie). – Bull. Jard. Bot. Natl. Belg. 39: 167-177.

Geerinck D. 1970. Révision du genre Anigozanthos Labill. (Haemodoraceae d’Australie). – Bull. Jard. Bot. Natl. Belg. 40: 261-276.

Givnish TJ, Evans TM, Pires JC, Sytsma KJ. 1999. Polyphyly and convergent morphological evolution in Commelinales and Commelinidae: evidence from rbcL sequence data. – Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 12: 360-385.

Glover DE, Barrett SCH. 1983. Trimorphic incompatibility in Mexican populations of Pontederia sagittata. – New Phytol. 95: 439-455.

Glover DE, Barrett SCH. 1986a. Pollen loads in tristylous Pontederia cordata populations from the southern USA. – Amer. J. Bot. 73: 1601-1621.

Glover DE, Barrett SCH. 1986b. Variation in the mating system of Eichhornia paniculata (Spreng.) Solms (Pontederiaceae). – Evolution 40: 1122-1131.

Gopal B. 1987. Water hyacinth. – Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. i-xii: 1-471.

Graham SW, Barrett SCH. 1995. Phylogenetic systematics of Pontederiales: implications for breeding-system evolution. – In: Rudall PJ, Cribb PJ, Cutler DF, Humphries CJ (eds), Monocotyledons: systematics and evolution, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, pp. 415-441.

Graham SW, Kohn JR, Morton BR, Eckenwalder JE, Barrett SCH. 1998. Phylogenetic congruence and discordance among one morphological and three molecular data sets from Pontederiaceae. – Syst. Biol. 47: 545-567.

Gravis A. 1898. Recherches anatomiques et physiologique sur le Tradescantia virginiana. – Mém. Acad. Roy. Sci. Belg. 57: 1-304.

Green JW. 1959. The genus Conostylis R. Br. I. Leaf anatomy. – Proc. Linn. Soc. New South Wales 84: 194-206.

Green JW. 1961. The genus Conostylis R. Br. II. Taxonomy. – Proc. Linn. Soc. New South Wales 85: 334-373.

Grootjen CJ. 1983. Development of ovule and seed in Cartonema spicatum R. Br. (Cartonemataceae). – Aust. J. Bot. 31: 297-305.

Grootjen CJ, Bouman F. 1981. Development of ovule and seed in Stanfieldiella imperforata (Commelinaceae). – Acta Bot. Neerl. 30: 265-275.

Hamann U. 1962a. Über Bau und Entwicklung des Endosperms der Philydraceae und über die Begriffe “mehliges Nährgewebe” und ”Farinosae”. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 81: 397-407.

Hamann U. 1962b. Weiteres über Merkmalsbestand und Verwandtschaftsbeziehungen der “Farinosae”. – Willdenowia 3: 169-207.

Hamann U. 1963. Die Embryologie von Philydrum lanuginosum (Monocotyledoneae-Philydraceae). – Ber. Deutsch. Bot. Ges. 76: 203-208.

Hamann U. 1966. Embryologische, morphologisch-anatomische und systematische Untersuchungen an Philydraceen. – Willdenowia, Beih. 4: 1-178.

Hamann U. 1998. Philydraceae. – In: Kubitzki K (ed), The families and genera of vascular plants IV. Flowering plants. Monocotyledons. Alismatanae and Commelinanae (except Gramineae), Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 389-394.

Handlos WL. 1975. The taxonomy of Tripogandra (Commelinaceae). – Rhodora 77: 213-333.

Hardy CR, Faden RB. 2004. Plowmanianthus, a new genus of Commelinaceae with five new species from tropical America. – Syst. Bot. 29: 316-333.

Hardy CR, Stevenson DW. 2000a. Development of gametophytes, flower and floral vasculature of Cochliostema odoratissimum (Commelinaceae). – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 134: 131-157.

Hardy CR, Stevenson DW. 2000b. Floral organogenesis in some species of Tradescantia and Callisia (Commelinaceae). – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 161: 551-562.

Hardy CR, Stevenson DW, Kiss HG. 2000. Development of the gametophytes, flower, and floral vasculature in Dichorisandra thyrsiflora (Commelinaceae). – Amer. J. Bot. 97: 1228-1239.

Hardy CR, Davis JR, Stevenson DW. 2004. Floral organogenesis in Plowmanianthus (Commelinaceae). – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 165: 511-519.

Hasskarl JK. 1870. Commelinaceae Indicae, Imprimis Archipelagi Indica. – M. Slazer, Wien.

Helme NA, Linder HP. 1992. Morphology, evolution, and taxonomy of Wachendorfia (Haemodoraceae). – Bothalia 22: 59-75.

Hertweck KL, Pires JC. 2014. Systematics and

evolution of inflorescence structure in the Tradescantia alliance (Commelinaceae). – Syst. Bot. 39:

105-116.

Hewson HJ. 1986. Hanguanaceae. – In: George AS (ed), Flora of Australia 46, Australian Government Publ. Service, Canberra, p. 172.

Hofreiter A, Tillich H-J. 2002. Root anatomy of the Commelinaceae (Monocotyledoneae). – Feddes Repert. 113: 231-255.

Holm T. 1906. Commelinaceae. Morphological and anatomical studies of the vegetative organs of some N. and C. American species. – Mem. Natl. Acad. Sci. 10: 159-192.

Hölscher D, Schneider B. 1997. Phenylphenalenones from root cultures of Anigozanthos preissii. – Phytochemistry 45. 87-91.

Hong D. 1974. Revisio Commelinacearum Sinacarum. – Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 12: 459-488.

Hooker JD. 1887. On Hydrothrix, a new genus. – Ann. Bot. 1: 89-94.

Hopper SD. 1978. Nomenclatural notes and new taxa in the Conostylis aculeata group (Haemodoraceae). – Nuytsia 2: 254-264.

Hopper SD. 1980a. A biosystematic study of the kangaroo paws, Anigozanthos and Macropidia (Haemodoraceae). – Aust. J. Bot. 28: 659-680.

Hopper SD. 1980b. Conostylis neocymosa sp. nov. (Haemodoraceae) from south-western Australia. – Bot. Not. 133: 223-226.

Hopper SD. 1993. Kangaroo paws and catspaws: a natural history and field guide. – Dept. of Conservation and Land Management, Perth.

Hopper SD, Burbidge AH. 1978. Assortative pollination by red wattlebirds in a hybrid population of Anigozanthos Labill. (Haemodoraceae). – Aust. J. Bot. 26: 335-350.

Hopper SD, Campbell NA. 1977. A multivariate morphometric study of species relationships in kangaroo paws (Anigozanthos Labill. and Macropidia Drumm. ex Harv.: Haemodoraceae). – Aust. J. Bot. 25: 523-544.

Hopper SD, Fay MF, Rossetto M, Chase MW. 1999. A molecular phylogenetic analysis of the bloodroot and kangaroo paw family, Haemodoraceae: taxonomic, biogeographic and conservation implications. – Bot. J Linn. Soc. 131: 285-299.

Hopper SD, Chase MW, Fay MF. 2006. A molecular phylogenetic study of generic and subgeneric relationships in the Southwest Australian endemics Conostylis and Blancoa (Haemodoraceae). – In: Columbus JT, Friar EA, Porter JM, Prince LM, Simpson MG (eds), Monocots: comparative biology and evolution. Excluding Poales, Rancho Santa Ana Botanical Garden, Claremont, California. – Aliso 22: 527-538.

Hopper SD, Smioth RJ, Fay MF, Manning JC, Chase MW. 2009. Molecular phylogenetics of Haemodoraceae in the Greater Cape and Southwest Australian floristic regions. – Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 51: 19-30.

Horn CN. 1985. A systematic revision of the genus Heteranthera (sensu lato; Pontederiaceae). – Ph.D. diss., University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

Horn CN. 1987. 205. Pontederiaceae. – In: Harling G, Sparre B (eds), Flora of Ecuador 29, Swedish Natural Science Research Council, Stockholm, pp. 1-19.

Horvat F. 1966. Contribution à la connaissance de l’ultrastructure des parois du pollen de Tradescantia paludosa L. – Grana Palynol. 6: 416-434.

Hunt DR. 1975. American Commelinaceae I. The reunion of Setcreasea and Separotheca with Tradescantia. – Kew Bull. 30: 443-458.

Hunt DR. 1978. American Commelinaceae IV. Three new genera in Commelinaceae. – Kew Bull. 33: 331-334.

Hunt DR. 1980. American Commelinaceae IX. Sections and series in Tradescantia. – Kew Bull. 35: 437-442.

Hunt DR. 1981. American Commelinaceae X. Precursory notes on Commelinaceae for the flora of Trinidad and Tobago. – Kew Bull. 36: 195-197.

Hunt DR. 1983. American Commelinaceae XI. New names in Commelinaceae. – Kew Bull. 38: 131-133.

Hunt DR. 1985. American Commelinaceae XII. A revision of Gibasis Rafin. – Kew Bull. 41: 107-129.

Hunt DR. 1986a. American Commelinaceae XIII. Campelia, Rheo, and Zebrina united with Tradescantia. – Kew Bull. 41: 401-405.

Hunt DR. 1986b. American Commelinaceae XV. Amplification of Callisia Loefl. – Kew Bull. 41: 407-412.

Hunt DR. 1993. The Commelinaceae of Mexico. – In: Ramamoorthy TP, Bye R, Lot A, Fa J (eds), Biological diversity of Mexico: origins and distribution, Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 421-437.

Husband BC, Barrett SCH. 1992. Genetic drift and the maintenance of the style length polymorphism in tristylous populations of Eichhornia paniculata (Pontederiaceae). – Heredity 69: 440-449.

Husband BC, Barrett SCH. 1993. Multiple origins of self-fertilization in tristylous Eichhornia paniculata (Pontederiaceae): inferences from style morph and isozyme variation. – J. Evol. Biol. 6: 591-608.

Iyengar MOT. 1923. On the biology of flowers of Monochoria. – J. Indian Bot. Soc. 3: 170-173.

Jacobs BF, Kabuye CHS. 1989. An extinct species of Pollia Thunberg (Commelinaceae) from the Miocene Ngorora Formation, Kenya. – Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 59: 67-76.

Jesson LK, Barrett SCH. 2002. Enantiostyly in Wachendorfia (Haemodoraceae): the influence of reproductive systems on the maintenance of the polymorphism. – Amer. J. Bot. 89: 253-262.

Jesson LK, Barrett SCH. 2003. The comparative biology of mirror-image flowers. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 164(Suppl.): S237-S249.

Jones K. 1974. Chromosome evolution by Robertsonian translocation in Gibasis (Commelinaceae). – Chromosoma 45: 353-368.

Jones K. 1990. Robertsonian change in allies of Zebrina (Commelinaceae). – Plant Syst. Evol. 172: 263-271.

Jones K, Jopling C. 1972. Chromosomes and the classification of the Commelinaceae. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 65: 129-162.

Jones K, Kenton A, Hunt DR. 1981. Contributions to the cytotaxonomy of the Commelinaceae. Chromosome evolution in Tradescantia section Cymbispatha. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 83: 157-188.

Kapil RN, Walia K. 1965. The embryology of Philydrum lanuginosum Banks ex Gaertn. and the systematic position of the Philydraceae. – Beitr. Biol. Pflanzen 41: 381-404.

Keighery GJ. 1981. Pollination and the generic status of Blancoa canescens Lindl. (Haemodoraceae). – Flora 171: 521-524.

Kenton A. 1978. Giemsa C-banding in Gibasis (Commelinaceae). – Chromosoma 65: 309-324.

Kohn JR, Barrett SCH. 1994. Pollen discounting and the spread of a selfing variant in tristylous Eichhornia paniculata: evidence from experimental populations. – Evolution 48: 1576-1594.

Kohn JR, Grahaw SW, Morton B, Doyle JJ, Barrett SCH. 1996. Reconstruction of the evolution of reproductive characters in Pontederiaceae using evidence from chloroplast DNA restriction-site variation. – Evolution 50: 1454-1469.

Larsen K. 1972. Flagellariaceae, Hanguanaceae. – Flora of Thailand 2(2): 162-166.

Larsen K. 1983. Hanguanaceae. – In: Leroy JF (ed), Flore du Cambodge, du Laos et du Viet-nam 20, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, pp. 129-132.

Lee RE. 1961. Pollen dimorphism in Tripogandra grandiflora. – Baileya 9: 53-56.

Lewis WH. 1964. Meiotic chromosomes in African Commelinaceae. – Sida 1: 274-293.

Lowden RM. 1973. Revision of the genus Pontederia. – Rhodora 75: 426-483.

Maas PJM, Maas-van der Kamer H. 1993. Flora Neotropica. Monograph 61. Haemodoraceae. – New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York.

Maas PJM, Maas-van der Kamer H. 2003. 201. Haemodoraceae. – In: Harling G, Andersson L (eds), Flora of Ecuador 71, Botanical Institute, Göteborg University, pp. 109-114.

MacFarlane TD, Hopper SD, Purdie RW, George AS, Patrick SJ. 1987. Haemodoraceae. – Flora of Australia 45, Australian Government Publ. Service, Canberra, pp. 55-148, 454-466.

Maheshwari SC, Baldev B. 1958. A contribution to the morphology of Commelina forskalaei Vahl. – Phytomorphology 8: 277-298.

Manning JC, Goldblatt P. 2017. A review of Dilatris P. J. Bergius (Haemodoraceae: Haemodoroideae). – South Afr. J. Bot. 113: 103-110.

Matthews JF. 1966. A paper chromatographic study of North and South American species of the genus Tradescantia. – Bot. Gaz. 127: 74-78.

Matuda E. 1955. Las Commelinaceae mexicanas. – Sobretiro de los Anales del Instituto de Biología 26: 303-432.

Maury P. 1888. Sur les affinités du genre Susum. – Bull. Soc. Bot. France 35: 410-417.

Mepham R, Lane G. 1969. Formation and development of the tapetal periplasmodium in Tradescantia bracteata. – Protoplasma 68: 175-192.