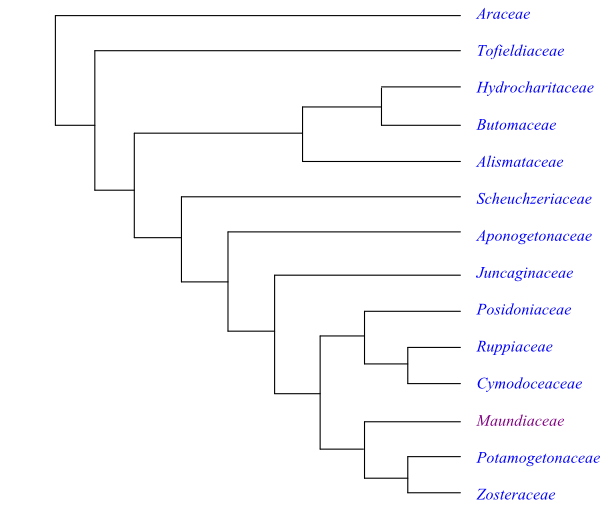

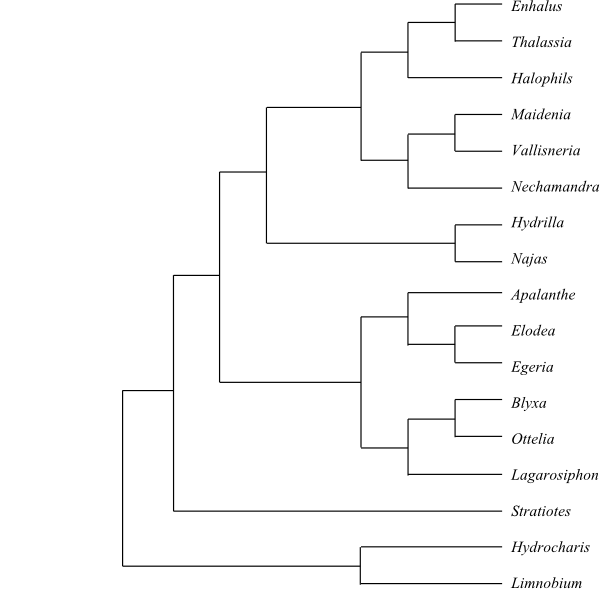

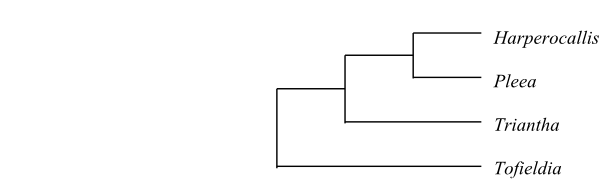

Cladogram of Alismatales based on DNA sequence data.

[Alismatales+[Petrosaviaceae+[Taccales+Pandanales]+[Liliales+[Iridales+Commelinidae]]]]

Alismatineae Engl., Syllabus, ed. 2: 73. Mai 1898; Alismatanae Takht., Sist. Filog. Cvetk. Rast. [Syst. Phylog. Magnolioph.]: 461. 4 Feb 1967; Alismatidae Takht., Sist. Filog. Cvetk. Rast. [Syst. Phylog. Magnolioph.]: 461. 4 Feb 1967

Fossils Pennistemon portugallicus is represented by a flower with spirally arranged stamens and pollen with reticulate exine and acolumellate granular infratectum. These and similar pollen grains (Pennipollis type) from the Late Aptian to the Cenomanian are known from Europe, Africa and North America. Pennicarpus tenuis consists of fossilized unilocular one-seeded fruits from the Early Cretaceous of Portugal, which may emanate from the same plants as Pennistemon. Thalassotaenia debeyi and other Maastrichtian and Danian fossils from western Europe comprise leaves similar to those of extant Cymodoceaceae or Posidonia. Numerous fruits from the Late Paleocene onwards of Asia and Europe resemble Ruppia and Potamogetonaceae and have been described under the name of Limnocarpus.

Habit Bisexual, monoecious, andromonoecious, gynomonoecious, polygamomonoecious, dioecious, or gynodioecious, usually perennial rhizomatous (rarely annual) herbs. Usually aquatic or hygrophilous (sometimes marine).

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza absent. Root stele often triarch to pentarch. Phellogen absent. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels often present in roots and sometimes in stem (sometimes entirely absent). Vessel elements with usually scalariform (sometimes simple, rarely reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform, simple pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2cs or P2cfs type (rarely Ss type?). Nodes multilacunar with several leaf traces. Laticifers sometimes present. Schizogenous ducts and cavities with resins and oils sometimes present. Trichosclereids sometimes present. Silica bodies absent. Calciumoxalate as raphides (H-shaped in cross-section), solitary prismatic crystals, or druses, or absent.

Trichomes Hairs usually absent (sometimes unicellular or multicellular, simple, lepidote, stellate, or prickly).

Leaves Alternate (spiral or distichous), compound (rarely pinnately compound) or simple, entire or lobed, often differentiated into pseudopetiole and pseudolamina, with supervolute, involute or convolute ptyxis (rarely absent). Pseudolamina usually developing from leaf base zone (sometimes from upper part of foliar primordium). Stipules absent or as axillary scales inside leaf sheath (rarely lateral); leaf sheath usually well developed, often with axillary intravaginal (sometimes hair-like) scales/colleters, squamulae intravaginales. Pseudopetiole vascular bundle transection arcuate; inverted bundles frequent. Venation usually pinnate or palmate, pedate, curvipalmate, parallelodromous, acrodromous, campylodromous, sometimes reticulodromous (then usually with tertiary veins). Stomata often absent (sometimes paracytic, tetracytic, anomocytic, or cyclocytic; adjacent cells with or without oblique divisions). Cuticular waxes absent. Mesophyll often with mucilaginous idioblasts containing calciumoxalate raphides, prismatic crystals or druses. Schizogenous laticiferous cavities sometimes present. Tanniniferous cells sometimes abundant. Leaf margin usually entire (sometimes serrate to dentate). Pseudolamina sometimes with apical pore.

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, simple or branched, panicle, spike or raceme, spike-, raceme- or umbel-like, or fleshy cymose spadix, or flowers solitary. Peduncle sometimes laticiferous. Inflorescence bract sometimes large and showy. Floral bracts and prophylls (bracteoles) often absent (lateral bracteole rarely present).

Flowers Usually actinomorphic (sometimes zygomorphic or asymmetrical). Hypanthium rarely present. Usually hypogyny (sometimes epigyny). Tepals (two or 2+2 or) 3+3 (rarely 4+4 or 6+6), all sepaloid or petaloid, or outer tepals sepaloid with valvate aestivation and inner tepals petaloid, crumpled in bud, free or entirely or partially connate, or absent. Septal nectaries present or absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens one to three, 2+2 or 3+3 (sometimes 18 to c. 100, rarely 4+4, 6+3, 6+4 or 6+6), whorled. Filaments short, free or sometimes connate into synandrium, usually free from tepals (rarely adnate to tepals, epitepalous). Anthers basifixed or subbasifixed, non-versatile, sometimes connate into synandrium, usually tetrasporangiate (sometimes disporangiate or 1–12-sporangiate), usually extrorse (rarely latrorse or introrse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits) or poricidal (dehiscing by apical or subapical pores, or short transverse slits); connective often expanded (laminar connective outgrowths sometimes perianth-like). Tapetum amoeboid-periplasmodial, with uninucleate cells. Staminodia usually absent (sometimes extrastaminal or intrastaminal; female flowers sometimes with staminodia).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis usually successive (sometimes simultaneous). Pollen grains sulcate, meridionosulcate (zonate), disulcate, trichotomosulcate, forate (periporate), di-, tri- or polypantoporate, or inaperturate, usually shed as monads (rarely tetrads), bicellular or tricellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate, usually with columellate (sometimes granular) infratectum, or intectate, reticulate, microreticulate, foveolate, foraminate, scabrate, spinulate, echinate, verrucate, fossulate, psilate, or smooth (rarely gemmate, areolate, rugulate, or striate), or absent.

Gynoecium Carpels (one to) three or six (to c. 100), in one whorl or seemingly spiral, secondarily free or connate at base, carpel plicate or conduplicate; or pistil composed of (one to) three (to 15) usually congenitally fused (rarely free) carpels; carpel ascidiate to intermediate, with completely non-fused canals, seemingly occluded by secretion. Closure by transverse slit occurring together with longitudinal slit. Ovary usually superior (sometimes inferior), usually unilocular to trilocular (to 47-locular), usually with mucilaginous hair on inner side. Style single, simple, usually very small, or absent, or stylodia terminal, lateral, gynobasic (sometimes connate at base) or absent. Stigma capitate, lobate or peltate, or stigmas usually linear, papillate or non-papillate, Dry or Wet type. Pistillodium usually absent (male flowers sometimes with pistillodia).

Ovules Placentation axile, parietal, basal, apical, laminar, or (sub)marginal. Ovules one to more than 100 per carpel, anatropous, hemianatropous, orthotropous, amphitropous, anacampylotropous, campylotropous or intermediate, ascending, horizontal or pendulous, apotropous, usually bitegmic (rarely unitegmic), usually tenuinucellar (sometimes crassinucellar or pseudocrassinucellar). Micropyle bistomal, endostomal or exostomal. Parietal cell formed from archesporial cell or absent. Nucellar cap often present. Megagametophyte usually monosporous, Polygonum type (rarely 10- to 12-nucleate; rarely disporous, Allium, Veratrum lobelianum, Endymion or Scilla type). Synergids often with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells usually persistent, often proliferating (sometimes absent). Endosperm development helobial or nuclear. Endosperm appendage (’endosperm haustorium’, ’basal apparatus’) chalazal. Embryogenesis onagrad, asterad, caryophyllad, or solanad.

Fruit Usually a berry, a drupe, a nut, a nutlike or drupaceous fruit, a loculicidal, septicidal or ventricidal capsule, or an assemblage of achenes or follicles (multifolliculus; rarely an indehiscent or dehiscent syncarp with baccate or nutlike mericarps).

Seeds Aril absent. Operculum sometimes present. Testa thick or thin, multiplicative, often parenchymatous (sometimes absent). Exotesta often fleshy and viscid, often with thick epidermal cell walls. Mesotesta sometimes parenchymatous. Endotesta sometimes absent. Mesotestal and endotestal cells usually thick-walled. Exotegmen often reduced or collapsing. Endotegmen tanniniferous or collapsing. Perisperm rarely developed. Endosperm copious, sparse or absent, starchy (starch grains usually Pteridophyte type, amylophilic) or with aleurone and lipids. Embryo large to small (often macropodous), straight or curved, sometimes with starch, well or poorly differentiated, sometimes with chlorophyll. Cotyledon one, not photosynthesizing. Cotyledon hyperphyll assimilating or modified into haustorium or nutrient-storing organ. Hypocotyl internode usually present (sometimes as swollen nutrient-storing organ). Coleoptile absent. Collar rhizoids or collar roots sometimes present. Radicula absent in some genera. Germination phanerocotylar. Seedling with hypocotyl and root well developed.

Cytology x = 5–15

DNA Deletion of 3 bp in atpA in many Alismatales (and in Acorus), but not in Tofieldiaceae or Cymodoceaceae; mitochondrial intron processing in most Alismatales according to cis-splicing mechanism

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), flavones, flavone-C-glycosides, flavone-O-glycosides, flavone aglucones, flavonoid sulfates, protocatechinic aldehyde, cyanidin, tannins, cinnamic acid, caffeic acid derivatives (including caffeic acid sulfate), chlorogenic acid, polyphenolic glycosides with caffeic acid, phenolic sulfates (sulfonated phenolic acids), alkaloids, tyrosine-derived cyanogenic glycosides (e.g. triglochinin), steroidal saponins, chelidonic acid, 5-alkylic- and 5-alkenylic resorcinols homogentisic acid and their glycosides, amines, and bitter substances present. Proanthocyanidins rare or absent. Ellagic acid not found. Sulphated compounds frequent in Juncaginaceae and some allied groups.

Systematics Alismatales are sister-group to all Liliidae except Acorus.

Squamulae intravaginales are a synapomorphy of a main clade in Alismatales (cf. Acoraceae). These structures are intravaginal or axillary non-vascularized scale-, gland- or finger-like trichomes occurring in pairs or multiples in the leaf axils. They are usually multicellular and two-layered and secrete a protective mucilage. Tanniniferous cells are often present at their base, in the middle parts, at the distal end or at the tooth-like border. Alismatales are one of the very few monocot clades in which chlorophyllous embryos have been found. Furthermore, Alismatales comprise most entirely marine angiosperms and the only known marine flowering plants, in which sulphated phenolic compounds are frequent. In some Alismatales intermediates between floral bracts and abaxial tepals seem to be present. It has been suggested that the flowers in at least many taxa are actually pseudanthia.

In most Alismatales, the leaves appear to have developed from the upper part of the leaf primordium (cf. Acorus). However, in many Araceae the leaves probably develop according to the normal monocotyledon principle.

Araceae are usually placed as sister-group to the remaining Alismatales, yet an unresolved basal trichotomy consisting of Araceae, Tofieldiaceae and the remainder has been identified in some analyses, and sometimes Tofieldiaceae are recovered as the sister-group either of all other Alismatales or to Araceae.

Apocarpous gynoecium is a synapomorphy of Alismatales except Araceae, according to Stevens (2001 onwards). Alismatales, except Araceae and Tofieldiaceae, are further characterized by the following potential synapomorphies: aquatic habit; stem with lacunae; absence of druses and raphides; absence of indumentum (trichomes) and bulliform cells; squamulae intravaginales often present; pseudolamina often with an apical pore; pollen grains tricellular at dispersal; absence of endosperm in mature seed; and presence of seedling collar and collar rhizoids.

The clade [Alismataceae+[Butomus+Hydrocharitaceae]] is characterized by, e.g.: bifurcating apical meristems of vegetative axes; inflorescence scapose, cymose and bracteate; outer tepals sepaloid and inner tepals petaloid; both perianth whorls with numerous leaf traces; stamens paired; carpels plicate; seed coat exotestal; and presence of flavone-C-glycosides. Butomus and Hydrocharitaceae have the character of ovary loculi with secretion in common.

The clade [Scheuchzeria+[Aponogeton+[Juncaginaceae+[[Posidoniaceae+[Ruppia+Cymodoceaceae]]+[Maundia+[Zosteraceae+Potamogetonaceae]]]]]] has a poorly developed radicula, and tepals (when present) with a single leaf trace.

The clade [Juncaginaceae+[[Posidonia+[Ruppia+Cymodoceaceae]]+[Maundia+[Zosteraceae+ Potamogetonaceae]]]] is characterized by the following potential synapomorphies (Stevens 2001 onwards): linear ligulate leaves with auriculate base; tepals absent or reduced to a retinaculum (‘abaxial outgrowths’ from the stamens); absence of nectary and filaments; pollen grains inaperturate; carpels with complete postgenital fusion; fruit indehiscent; endosperm development nuclear; presence of sulphated phenolic acids; and absence of flavones and proanthocyanidins.

The clade [[Posidonia+[Ruppia+Cymodoceaceae]]+[Maundia+[Zosteraceae+Potamo-getonaceae]]] has, e.g., the following characteristic features: rhizome with endodermis; epidermis with chlorophyll; one apical orthotropous ovule per carpel; fruit drupaceous; embryo with a massive elongate hypocotyls; and collar or base of hypocotyls much enlarged. [Posidonia+[Ruppia+Cymodoceaceae]] lack vessels, have distichous leaves without stomata, and produce filiform pollen grains. Ruppia and Cymodoceaceae have serrulate leaves and two stamens.

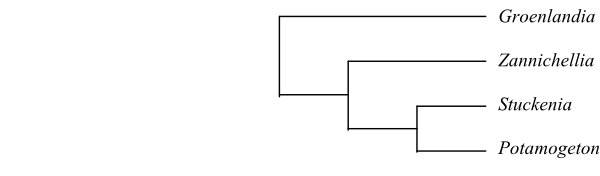

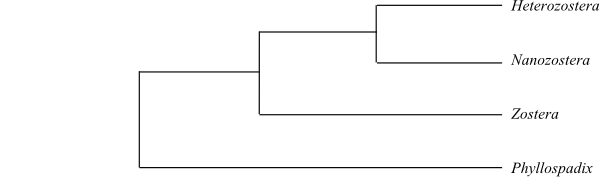

The [Zosteraceae+Potamogetonaceae] clade has the following potential synapomorphies: flowers unisexual; leaf sheath closed; leaves with an apical pore (also present in Scheuchzeria); and staminal pair with a single vascular trace. So far, no obvious morphological synapomorphy uniting Maundia with Zosteraceae and Potamogetonaceae has been found. On the other hand, Maundia is still very poorly investigated.

Petersen & al. (2016) found Acorus as sister to all Alismatales except Tofieldiaceae and Araceae. However, Acorus appeared outside of the Alismatales clade in the analysis by Ross & al. (2016).

According to Ross & al. (2016) and Petersen & al. (2016), Aponogeton (Aponogetonaceae) was sister-group to the remaining Alismatales (with low to moderate support), whereas Scheuchzeria (Scheuchzeriaceae) was successive sister to the rest. Both studies recovered the alternative topology [Maundiaceae+[[Potamogetonaceae+Zosteraceae]+[Posidoniaceae+[Ruppiaceae+Cymodoceaceae]]]].

|

Cladogram of Alismatales based on DNA sequence data. |

ALISMATACEAE Vent. |

( Back to Alismatales ) |

Damasoniaceae Nakai, Chosakuronbun Mokuroku [Ord. Fam. Trib. Nov.]: 213. 20 Jul 1943; Elismataceae Nakai, Chosakuronbun Mokuroku [Ord. Fam. Trib. Nov.]: 213. 20 Jul 1943, nom. illeg.; Limnocharitaceae Takht. ex Cronq., Integr. Syst. Class. Fl. Pl.: 1048. 10 Aug 1981

Genera/species 18/100–105

Distribution Allmost cosmopolitan, with their highest diversity in North and South America.

Fossils Cardstonia tolmanii comprises fossilized leaves from the Campanian to the Maastrichtian of Alberta. Moreover, fruits and seeds of Alismataceae are frequent in Cenozoic layers from the Eocene onwards.

Habit Usually bisexual (sometimes unisexual: in Sagittaria monoecious or polygamomonoecious, in Limnophyton polygamomonoecious, in Burnatia dioecious), usually perennial (rarely annual) herbs. Aquatic or helophytic. Tuberous stem, corm or stolons sometimes present.

Vegetative anatomy Roots fibrous, often septate. Turions sometimes formed (e.g. in Sagittaria). Phellogen absent. Secondary lateral growth absent. Rhizome in Limnochariteae and allied genera with endodermis (similar to root endodermis). Vessels in roots only, as a single vascular strand (sometimes absent). Vessel elements usually with simple (sometimes scalariform) perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystalloid bodies, without starch or protein filaments. Nodes? Schizogenous ducts with milky latex. Calciumoxalate as druses and single prismatic crystals.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate or stellate, or absent.

Leaves Alternate (spiral or distichous), simple, entire, often differentiated into pseudopetiole and pseudolamina, with involute or supervolute ptyxis. Stipules as axillary scales inside leaf sheath (primary leaves in some genera with lateral stipules); leaf sheath well developed; intravaginal scales absent? Venation parallelodromous; mid-vein prominent; usually with transveral veins between primary veins; secondary and tertiary venation reticulate; inverted vascular bundles sometimes present. Stomata usually paracytic, with parallel cell divisions of subsidiary cells (rarely tetracytic). Cuticular wax absent. Mesophyll with prismatic calciumoxalate crystals or druses. Schizogenous secretory cavities with latex. Leaf margin entire (sometimes undulating). Heterophylly frequently occurring. Abaxial surface with an apical subepidermal pore. Extrafloral nectaries present or absent.

Inflorescence Usually terminal or axillary, paniculate, whorled, spike- or umbel-like, with one verticil (flowers sometimes solitary axillary). Sometimes with involucre-like bracts.

Flowers Actinomorphic. Hypogyny. Tepals 3+3, free; outer tepals sepaloid, with valvate aestivation, sometimes persistent; inner tepals petaloid, thin, crumpled in bud (in Burnatia reduced or absent), caducous. Gynoecial-septal nectaries present on lateral walls of carpel bases (in Echinodorus also at tepal bases or stamens; in Sagittaria also on staminodia and filaments of fertile stamens; nectar in Limnocharis and allied genera secreted on entire surface of ovaries). Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens three, six (paired, antesepalous, alternipetalous), 6+3 or numerous (18 to c. 100), whorled (often seemingly spiral). Filaments simple, free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed or subbasifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, usually extrorse (in Limnochariteae and allied genera usually latrorse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum amoeboid-periplasmodial, with uninucleate cells. Outer staminal whorl in, e.g., some species of Hydrocleys and Limnocharis transformed into extrastaminal staminodia.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains 9–30-pantoporate (rarely di- or triporate or inaperturate), shed as monads, tricellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum, foraminate, usually spinulate (in, e.g., Limnocharis and Alisma granulate). Pollen grains often starchy. Excess pollen in one carpel grow out of this carpel through flower base and into another carpel (Endress 2011).

Gynoecium Carpels six, nine (to 20, rarely 20 to c. 100), in a single whorl or seemingly spiral, ab initio antesepalous (sometimes on gynoecial bulges), free (secondary apocarpy) or connate at base; carpel plicate and ascidiate. Ovaries superior, unilocular. Styluli terminal, lateral, gynobasic or absent. Stigmas usually linear (in Limnocharis capitate, in Butomopsis and Hydrocleys hippocrepomorphic), papillate, Dry type. Pistillodia usually absent (male flowers sometimes with pistillodia).

Ovules Placentation in Limnocharis, Butomopsis and Hydrocleys laminar-diffuse (lateral, ovules scattered over carpellary surface), in Alismateae usually basal (in Damasonium marginal). Ovules usually one (sometimes two; in Damasonium two to ten), in Limnocharis, Butomopsis and Hydrocleys numerous per carpel, usually anatropous (rarely campylotropous or amphitropous), ascending, apotropous, bitegmic, tenuinucellar or pseudocrassinucellar. Micropyle usually endostomal. Outer integument two or three cell layers thick. Inner integument approx. two cell layers thick. Parietal tissue often not formed. Nucellar cap formed by periclinal cell divisions of megasporangial epidermis. Megagametophyte usually tetrasporic, quadrinucleate, Allium type (sometimes monosporic, quadrinucleate). Synergids usually with a filiform apparatus. Endosperm development ab initio helobial (Echinodorus, Limnophyton, Sagittaria, Limnocharis, Butomopsis and Hydrocleys) or nuclear (Alisma, Damasonium, Luronium). Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis caryophyllad.

Fruit Usually an assemblage of achenes (in Limnocharis, Butomopsis, Hydrocleys and Damasonium polyspermum follicles), often with persistent style and sometimes persistent outer tepals.

Seeds Aril absent. Seeds U-shaped. Seed coat testal(-tegmic). Exotesta with thickened epidermal cell walls. Testal cells in Limnocharis thin-walled, with upright ends (in Butomopsis and Hydrocleys with glandular hairs). Tegmen more or less reduced or with thickened cell walls. Perisperm? starchy. Endosperm absent. Basal suspensor cell enlarged. Embryo hippocrepomorphic, without chlorophyll. Cotyledon one. Cotyledon hyperphyll elongate, assimilating. Hypocotyl internode present (in Baldellia long). Coleoptile absent. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology x = 5–13 (x = 11) – Chromosomes 2,4–14,4 μm in length (in Limnocharis, Butomopsis and Hydrocleys 2,6–13,6 μm).

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), flavone-C-glycosides (Sagittaria), flavone sulphates, cyanidin, tannins (Echinodorus, Luronium, Wiesneria), phenolic sulphates, and alkaloids present. Proanthocyanidins usually absent. Ellagic acid and saponins not found. Rhizome containing starch and sugar.

Use Ornamental plants, aquarium plants, vegetables (corms and roots of Sagittaria, leaves of Limnocharis), forage plants.

Systematics Alismataceae are sister-group to [Butomaceae+Hydrocharitaceae]. A comprehensive molecular phylogenetical investigation of Alismataceae is needed.

Alismateae Dumort., Fl. Belg.: 135. 1827 [‘Alismeae’]

4/19. Luronium (1; L. natans; western Europe to Scandinavia), Damasonium (6; D. alisma, D. bourgaei, D. californicum, D. constrictum, D. minus, D. polyspermum; West and Central Europe, the Mediterranean, Russia, western and Central Asia, India, North Africa, southeastern Australia, Tasmania, western United States), Baldellia (3; B. alpestris: northern Iberian Peninsula; B. ranunculoides: the Azores, Europe, the Mediterranean to Turkey, Morocco; B. repens: the Canary Islands, Europe, Algeria), Alisma (9; temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere). – Temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere. – Baldellia is sister to [Alisma+Luronium] in a study of Baldellia phylogeny by Arrigo & al. (2011).

Limnochariteae Pichon in Notul. Syst. 12: 183. Feb 1946

14/c 85. Burnatia (1; B. enneandra; tropical to southern Africa), Limnocharis (2; L. flava, L. laforestii; Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America), Butomopsis (1; B. latifolia; tropical Africa, South Asia to northern Australia), Hydrocleys (5; H. martii, H. mattogrossensis, H. modesta, H. nymphoides, H. parviflora; Central America, tropical South America); Albidella (1; A. nymphaeifolia; tropical Africa, coastal areas along the Indian Ocean to tropical Australia, Yucatán and Cuba), Ranalisma (2; R. humile: tropical Africa; R. rostrata: India, Southeast Asia, southern China), Helanthium (3; H. bolivianum, H. tenellum, H. zombiense; eastern United States, southern Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America), Caldesia (3; C. grandis, C. oligococca, C. parnassifolia; central, southern and eastern Europe, Africa, Asia to tropical Australia), Echinodorus (28; southern United States to tropical South America), Albidella (1; A. nymphaeifolia; Mexico, Honduras, Cuba), Sagittaria (c 30; America, few species in Europe, Africa and Asia), Wiesneria (3; W. schweinfurthii: tropical Africa; W. filifolia: Madagascar; W. triandra: southern India), Limnophyton (3; L. angolense, L. fluitans, L. obtusifolium; tropical Africa, Madagascar, South and Southeast Asia, Malesia), Astonia (1; A. australiensis; northeastern Queensland). – Pantropical, Eurasia, eastern and southern North America.

|

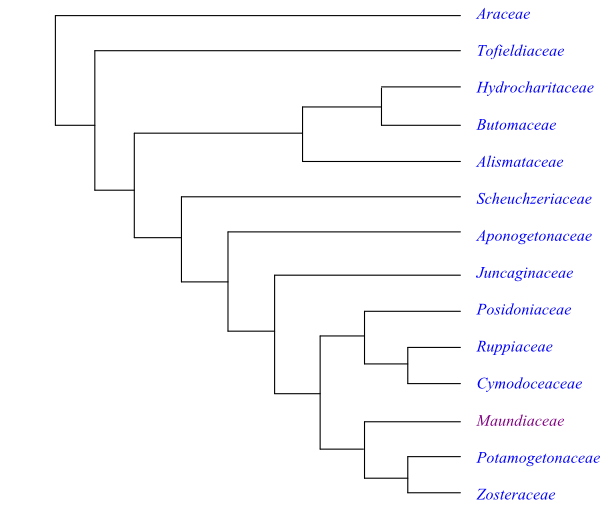

Phylogeny (Bayesian tree, simplified) of Alismataceae based on DNA data (Chen & al. 2012; Butomopis added according to Chen & al. 2013). Burnatia is sister-group to [Luronium+[Damasonium+[Baldellia+Alisma]]] and Albidella sister to the majority of Limnochariteae, according to Lehtonen (2017). |

APONOGETONACEAE Planch. |

( Back to Alismatales ) |

Aponogetonales Hutch., Fam. Fl. Pl., Monocot.: 10, 43. 20 Jul 1934

Genera/species 1/50–55

Distribution Tropical and subtropical regions of the Old World, with their largest diversity in southern Africa and Madagascar.

Fossils Fossil leaves similar to Aponogeton have been found in Late Oligocene layers in Central Asia.

Habit Usually monoecious (rarely dioecious or bisexual?), perennial herbs with corm or rhizome. Aquatic.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen absent. Apical stem meristem usually bipartite. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels usually absent (rarely present in roots, with scalariform perforation plates and ? lateral pits). Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystalloid bodies, without starch or protein filaments. Nodes? Articulated laticifers containing tannins or oils. Calciumoxalate crystals present in rhomboedrical aggregations.

Trichomes Hairs absent.

Leaves Alternate (spiral), simple, often differentiated into pseudopetiole and pseudolamina, entire, with involute or supervolute ptyxis. Stipules absent; leaf sheath well developed, with axillary intravaginal scales, squamulae intravaginales. Venation parallelodromous, with transversal veins connecting primary veins; tertiary veins absent (leaves in Aponogeton madagascariensis reticulate, fenestrate, due to absence of mesophyll between veins). Stomata paracytic. Cuticular wax absent. Mesophyll cells in floating leaves with rhomboedrical accumulations of calciumoxalate crystals. Leaf margin entire. Old pseudolamina with apical pore. Heterophylly often present.

Inflorescence Terminal, with flowers usually spirally arranged in one to 15 spike-like, simple or branched, inflorescences above water level (in Aponogeton ranunculiflorus reduced into few-flowered pseudanthia); each inflorescence as young surrounded by a usually caducous spathe-like bract. Peduncle (scape) with articulated laticifers. Floral bracts absent.

Flowers More or less zygomorphic, small. Hypogyny. Tepals usually two (abaxial lateral, corresponding to inner? tepals; rarely one tepal [one tepal possibly adnate to bract]; in Aponogeton hexatepalus six tepals), petaloid, usually persistent (rarely caducous), free (absent in female flowers of dioecious species). Gynoecial-septal nectaries usually present on lateral walls of carpel bases. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens usually 3+3 (in Aponogeton distachyos eight to 16 in several whorls, sometimes paired). Filaments free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, usually extrorse (sometimes introrse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum amoeboid-periplasmodial, with ab initio uninucleate cells. Female flowers in monoecious species with staminodia.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive or simultaneous. Pollen grains monosulcate, shed as monads, usually tricellular (sometimes bicellular) at dispersal. Exine semitectate, with columellate infratectum, perreticulate, beset with supratectal spinules.

Gynoecium Carpels (two or) three (to nine), alternitepalous, free or connate at base; odd carpel anterior (carpella anterioris). Ovary superior, unilocular (apocarpy). Stylulus short. Stigma adaxially decurrent, papillate, Dry type. Male flowers with pistillodia.

Ovules Placentation basal or marginal. Ovules (one or) two to twelve per carpel, anatropous to hemianatropous, ascending, usually bitegmic (in Aponogeton distachyos unitegmic), crassinucellar. Micropyle ?-stomal. Outer integument usually three cell layers thick. Inner integument two cell layers thick. Parietal cell formed from archesporial cell. Nucellar cap formed by periclinal divisions of megasporangial epidermal cells. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Antipodal cells not proliferating. Endosperm development helobial. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis caryophyllad (sometimes Sagittaria type).

Fruit A multifolliculus with almost free (basally connate) individual follicles.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat testal, mucilaginous. Exotesta thick or thin. Mesotesta often parenchymatous. Endotesta present or absent. Exotegmen collapsing. Endotegmen tanniniferous, or thin and undifferentiated. Perisperm not developed. Starch present. Endosperm absent. Suspensor absent. Embryo straight, with or without chlorophyll. Cotyledon one, large, bifacial. Cotyledon hyperphyll elongate, assimilating. Hypocotyl internode short. Coleoptile absent. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 8, 12, 16, 20, 28 – Polyploidy and aneuploidy frequently occurring. Agamospermy occurring. Chromosomes 0,7–2,3 μm long.

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), cyanidin, tannins (in isolated leaf cells), polyphenolic glycosides with caffeic acid, proanthocyanidins, and chlorogenic acid present. Flavone-C-glycosides, ellagic acid, alkaloids, saponins, cyanogenic compounds, and cell wall bound ferulate not found.

Use Ornamental plants, aquarium plants, vegetables.

Systematics Aponogeton (50–55; Africa south to the Cape Provinces, Madagascar, India to Malesia and northern Australia).

Aponogetonaceae are usually sister-group to the clade [Juncaginaceae+[[Posidoniaceae+ [Ruppia+Cymodoceaceae]]+[Maundia+[Zosteraceae+Potamogetonaceae]]]], although Apono-geton has sometimes been recovered as sister to Scheuchzeria (Kato & al. 2003).

ARACEAE Juss. |

( Back to Alismatales ) |

Arales Juss. ex Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 263. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Aroideae’]; Lemnaceae Gray, Nat. Arr. Brit. Pl. 2: 729. 10 Jan 1822 [‘Lemnadeae’], nom. cons.; Pistiaceae Rich. ex C. Agardh, Aphor. Bot. (9): 130. 19 Jun 1822; Lemnales Link, Handbuch 1: 289. 4-11 Jul 1829 [‘Lemnaceae’]; Aropsida Bartl., Ord. Nat. Pl.: 25, 65. Sep 1830 [’Aroideae’]; Callaceae Reichb. ex Bartl., Ord. Nat. Plant.: 25, 66. Sep 1830; Orontiaceae Bartl., Ord. Nat. Plant.: 24, 68. Sep 1830; Pistiales Rich. in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp. Regn. Veg.: 5. Sep-Oct 1835 [’Pistiaceae’]; Arisaraceae Raf., Fl. Tellur. 4: 16. med 1838 [’Arisaria’]; Pothaceae Raf., Fl. Tellur. 4: 16. med 1838 [‘Pothidia’]; Orontiales J. Presl in Nowočeská Bibl. [Wšobecný Rostl.] 7: 1653 ['1553']. 1846 [‘Orontiaceae’]; Cryptocorynaceae J. Agardh, Theoria Syst. Plant.: 32. Apr-Sep 1858 [‘Cryptocoryneae’]; Caladiaceae Salisb., Gen. Plant.: 5. 15-31 Mai 1866 [‘Caladeae’]; Dracontiaceae Salisb., Gen. Plant.: 7. 15-31 Mai 1866 [‘Draconteae’]; Colocasiaceae Vines, Stud. Text-book Bot. 2: 541. Mar 1895 [’Colocasioideae’]; Lasiaceae Vines, Stud. Text-book Bot. 2: 540. Mar 1895 [‘Lasioideae’]; Monsteraceae Vines, Stud. Text-book Bot. 2: 540. Mar 1895 [‘Monsteroides’]; Philodendraceae Vines, Stud. Text-book Bot. 2: 540. Mar 1895 [‘Philodendroideae’]; Wolffiaceae (Gray) Bubani, Fl. Pyren. 4: 22. 15-28 Feb 1902; Aranae Thorne ex Reveal in Novon 2: 235. 13 Oct 1992; Aridae Takht., Divers. Classif. Fl. Pl.: 579. 24 Apr 1997

Genera/species 117/3.440–3.475

Distribution Mainly tropical but also subtropical regions, and approx. ten genera in temperate regions in the Northern Hemisphere.

Fossils The fossil record of Cretaceous and Cenozoic Araceae is very rich, with a peak during the Paleocene and Eocene (e.g. with the Proxapertites pollen type). Fossils of Orontium have been found in Late Cretaceous and Eocene layers in North America. Fossil stems, leaves, stamens and pollen of Limnobiophyllum have been found in Late Cretaceous to Miocene layers of Europe, Israel, North America and East Asia. Limnobiophyllum had stolons and rosettes of floating leaves or foliaceous branches. This genus has often been interpreted as intermediary between Lemnoideae and other Araceae and is placed in cladistic analyses as sister to Lemnoideae. Fossil pollen grains of Pothooideae-Monstereae are known from the Late Barremian to the Early Aptian of Portugal. These include the Early Cretaceous Mayoa portugallica, if correctly interpreted as a fossil pollen, inaperturate, with striate exine and granular infratectum, similar to Holochlamys in Monsteroideae. Pennipollis may possibly belong here. The Proxapertites pollen grains have a tectate exine, an acolumellate infratectum and an aperture encircling the equator. The infructescence Albertarum pueri from the Campanian of Alberta has been assigned to Orontioideae, and leaves resembling Orontioideae were described from the Early Campanian to Maastrichtian of Europe and North America. Leaves of Cobbania have been found in the Campanian to the Maastrichtian of Asia and North America. Fossil flowers, fruits and seeds occur in Cretaceous and Cenozoic layers of North America and Europe, and Neogene seeds of Araceae (e.g. Pistia) are frequent in European and Siberian lignites. Lasioideaecidites, from the latest Campanian to the earliest Maastrichtian Vilui Basin sediments in Siberia, was assigned to Lasioideae.

Habit Bisexual, monoecious (often with female flowers in lower part of inflorescence and male flowers in middle and upper parts), andromonoecious, gynomonoecious, polygamomonoecious, dioecious, or gynodioecious, usually perennial (rarely annual) herbs (some are giant herbs, whereas others are extremely small [e.g. Wolffia]), often epiphytic or climbing with stem or roots (rarely suffrutices). In the aquatic Lemnoideae, leaves are absent and the stem is reduced to a usually flat thalloid floating structure with or without roots on the lower side. Some genera have a starchy stem tuber (e.g. in Lasioideae and Aroideae). Many representatives are aquatic (e.g. Pistia) or hygrophilous. Turions are formed in, e.g., Spirodela, Wolffia and some species of Lemna.

Vegetative anatomy Roots with mycorrhiza. Water-absorbing velamen, formed from epidermis, present in some representatives (e.g. Anthurium). Root hypodermis dimorphic. Phellogen absent. Secondary lateral growth absent? Vessels present in roots in many species (in some species also in stems). Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids usually P2c, P2cs or P2cfs type (in Pistia Ss type). Nodes multilacunar with several leaf traces. Laticifers (simple or branched, sometimes anastomosing) usually present; latex white or colour-less, often tanniniferous. Schizogenous canals and cavities with resins and oils present in some genera. Trichosclereids abundant in Spathiphylleae and Monstereae. Calciumoxalate as ‘twinned’ raphides (H-shaped in cross-section), druses, prismatic crystals, etc. Silica bodies absent.

Trichomes Hairs usually absent (rarely unicellular or multicellular, lepidote, or as prickles; in Pistia ‘jointed’ uniseriate hairs).

Leaves Alternate (spiral), compound (rarely pinnately compound) or simple, entire or lobed (sometimes fenestrate or perforate; rarely peltate), usually differentiated into pseudopetiole and pseudolamina, or absent (in Lemnoideae), with supervolute ptyxis. Stipules absent; leaf sheath usually well developed (some genera with axillary intravaginal hair-like scales/colleters, squamulae intravaginales). Pseudopetiole often with distal pulvinus, geniculum. Vascular bundles of pseudopetiole scattered. Venation usually pinnate or palmate (sometimes pedate, arcuate from leaf base, curvipalmate, parallelodromous, etc.; only in Gymnostachys distinctly parallel), acrodromous, campylodromous etc.; mid-vein compound; fine venation reticulate to parallel-pinnate (parallel to primary lateral veins). Stomata usually paracytic (sometimes anomocytic, cyclocytic, or tetracytic); adjacent cells usually dividing. Cuticular wax crystalloids as non-orientated platelets, threads or tubuli, or absent. Mesophyll often with mucilage cells containing calciumoxalate raphides. Leaf margin usually entire. Extrafloral nectaries present in some species.

Inflorescence Usually a terminal, thick fleshy cymose spadix (in Lemnoideae reduced to one or two flowers) usually with spiral (rarely whorled) flowers subtended by a usually showy bract, spathe, often with odorous appendage (in Gymnostachys, Orontium and Lemnoideae very small or strongly reduced). Floral prophylls (bracteoles) and bracts absent.

Flowers Actinomorphic to asymmetrical, small (in Lemnoideae extremely small and strongly reduced). Hypogyny. Tepals 2+2 or 3+3 (when dimerous then outer tepals lateral; when trimerous then median tepal in outer whorl adaxial; rarely 4+4 or 6+6), sepaloid, scale-like, free or entirely or partially connate, or absent. Septal nectaries absent (perigonal nectaries present in Anthurium; staminodial nectaries in Aglaonema). Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens one, 2+2 or 3+3 (rarely 4+4 or 6+6), antetepalous. Filaments short, free or connate into a synandrium, free from tepals. Anthers usually basifixed (sometimes ventrifixed), non-versatile, sometimes connate into a synandrium, usually tetrasporangiate (sometimes disporangiate), usually extrorse (rarely latrorse or introrse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits) or poricidal (dehiscing by apical or subapical pores, or short transversal slits); connective often expanded. Tapetum amoeboid-periplasmodial, with usually uninucleate (some species with binucleate) cells. Female flowers sometimes with staminodia.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis usually successive (rarely simultaneous). Pollen grains sulcate, meridionosulcate (zonate), disulcate (diaperturate), forate (periporate), or inaperturate (omniaperturate), usually shed as monads (rarely tetrads), bicellular or tricellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate or granular infratectum, or intectate, pertectate, perforate, reticulate or foveolate, smooth, psilate, scabrate, spinulate, or fossulate (rarely gemmate, verrucate, areolate, regulate, or striate); endexine spongy. Pollen grains usually starchy.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (one to) three (to 15) usually congenitally fused (rarely free) carpels; carpel ascidiate to intermediate, eusyncarpous, seemingly occluded by secretion. Ovary superior, usually unilocular to trilocular (in Spathicarpeae unilocular to octolocular; in Philodendron bilocular to 47-locular), usually with a mucilaginous hair on inner side. Style single, usually very small, or absent. Stigma capitate or lobate, non-papillate, Dry or Wet type. Male flowers sometimes with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation axile to parietal, basal to apical. Ovules one or few to numerous per carpel, anatropous, hemianatropous, orthotropous, amphitropous, anacampylotropous or intermediate, pendulous, horizontal or ascending, usually bitegmic (in Gymnostachys unitegmic), usually tenuinucellar or pseudocrassinucellar (in, e.g., Calla and Symplocarpus crassinucellar). Micropyle bistomal or exostomal. Outer integument (two to) eight to 26 cell layers thick (at base). Inner integument two to ten cell layers thick. Parietal cell often formed from archesporial cell. Nucellar cap, usually two or three cell layers thick, formed by periclinal cell divisions of megasporangial epidermis. Megagametophyte usually monosporous, Polygonum type (in Nephthytis 10- to 12-nucleate; in Lemna, Wolffia and Wolffiella disporous, Allium or Scilla type). Antipodal cells sometimes proliferating. Hypostase present or absent. Endosperm development usually ab initio helobial or nuclear; first cell division usually very asymmetrical; subsequent initial divisions often entirely in micropylar chamber. Endosperm appendage (’endosperm haustorium’, ’basal apparatus’) chalazal. Embryogenesis onagrad, asterad, caryophyllad, or solanad.

Fruit Usually a juicy berry (sometimes dry or leathery; in Lagenandra dehiscing at base; in some genera fused into an indehiscent or dehiscent syncarp), often with mucilaginous envelope and sometimes partially mucilaginous pericarp; in Lemnoideae a nutlike fruit.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa thick or thin, multiplicative, often parenchymatous (absent in Gymnostachys, Nephthytis and Orontium). Operculum present. Exotesta often fleshy and viscid. Mesotestal and endotestal cells usually thick-walled. Tegmen unspecialized, often collapsing. Perisperm rarely present (in, e.g., Pistia). Endosperm copious, sparse or absent, starchy or with aleurone and lipids. Embryo large to small (often macropodous), straight or curved, with or without starch, usually little differentiated, usually with chlorophyll. Cotyledon one, not photosynthesizing. Cotyledon hyperphyll assimilating or transformed into haustorium or nutrient-storing organ. Hypocotyl internode usually present (sometimes as a swollen nutrient-storing organ). Coleoptile absent. Collar rhizoids or collar roots sometimes present. Radicula absent in some genera. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 7–84 – Polyploidy and aneuploidy frequent in some genera.

DNA Mitochondrial coxI intron present in numerous genera.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), O-flavones, flavone-C-glycosides, cyanidin, ethereal oils (in, e.g., Homalomena), cinnamic acid, alkaloids (including benzylisoquinoline alkaloids), cyanogenic glycosides (triglochinin etc.), steroidal saponins, tyrosine-dervided cyanogenic substances, amines, and bitter substances present as well as several irritating or allergenic substances (e.g. protocatechinic aldehyde, homogentisic acid and their glycosides, and 5-alkylic- and 5-alkenylic resorcinols). Ellagic acid and chelidonic acid not found.

Use Ornamental plants, aquarium plants (Cryptocoryne, Pistia etc.), starch sources and vegetables (Colocasia esculenta, Xanthosoma sagittifolium, Amorphophallus paeoniifolius), fruits (Monstera deliciosa), gels in food-stuffs (A. konjac), medicinal plants, arrow poisons, fibres for basketry, animal forage (Lemnoideae).

Systematics Araceae are sister-group to the remaining Alismatales. The clade [Gymnostachys+Orontioideae] is sister to all other Araceae and characterized by, e.g., continuous tectum, orthotropous ovule, an inner integument three or four cell layers thick and multiplicative, and a seedling possessing cataphylls.

[Gymnostachys+Orontioideae]

Gymnostachydoideae Bogner et Nicolson in Willdenowia 21: 37. 11 Dec 1991

1/1. Gymnostachys (1; G. anceps; eastern Queensland, eastern New South Wales). – Vascular bundles with fibre envelopes and girders. Leaves distichous, linear, without pseudopetiole. Venation parallelodromous. Stomata parallel to foliar axis. Leaf margin finely serrate. Inflorescence complex, branched. Spatha absent. Flowers dimerous. Tepals four. Stamens four. Anther thecae running out in a tip above the slit. Pistil composed of a single ascidiate carpel. Ovary unilocular, with non-secreting? locule. Stigma Dry type. Placentation apical. Ovule one per carpel, orthotropous, unitegmic. Micropyle absent. Testa absent. Endosperm copious, starchy, with chlorophyll. Embryo with chlorophyll. Collar rhizoids absent. n = 12. – Gymnostachys is sister-group to the remaining Araceae, according to some molecular analyses. On the other hand, Cabrera & al. (2008) identified Gymnostachys as sister to Orontioideae.

Orontioideae R. Br. ex Müll. Berol. in Ann. Bot. Syst. 5: 898. 1860 [‘Orontiaceae’]

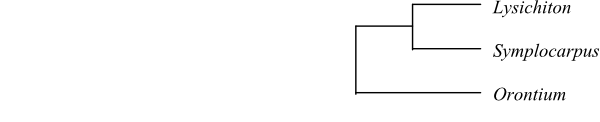

3/8. Orontium (1; O. aquaticum; southeastern Canada, eastern United States), Lysichiton (2; L. camtschatcensis: Kamchatka, Sakhalin, the Kuriles; L. americanus: western North America), Symplocarpus (5; S. egorovii, S. nabekuraensis, S. nipponicus, S. renifolius: northeastern Asia; S. foetidus: southeastern Canada, northeastern United States). – Temperate East Asia, western and eastern North America. Collenchyma sometimes arranged in cortical bands. Vascular bundles often with fibre strands. Simple laticifers present in Orontium. Sieve tube plastids without starch. Leaves spiral, elliptic. Spatha absent in Orontium. Tepals usually 2+2 (in Orontium usually 3+3). Usually epigyny (in Orontium hypogyny). Ovary unilocular or bilocular. Placentation basal or subbasal. Ovule one or two per carpel, usually orthotropous (in Orontium hemianatropous), crassinucellar. Outer integument 22 or more cell layers thick (integument in Symplocarpus lobate). Inner integument five to ten cell layers thick. Parietal tissue usually present. Endosperm absent or rudimentary. n = 13–15. Flavonols present. Flavone glycosides absent. – Orontium is sister to [Lysichiton+Symplocarpus].

[Lemnoideae+[[Pothoideae+Monsteroideae]+[Lasioideae+[Zamioculcadoideae s.lat.+Aroideae]]]]

Megasporangial tissue disappearing during maturation of the ovule. Endothelium present. (Steven 2001 onward)

Lemnoideae Bab., Man. Brit. Bot.: 320. Mai-Jul 1843 [‘Lemneae’]

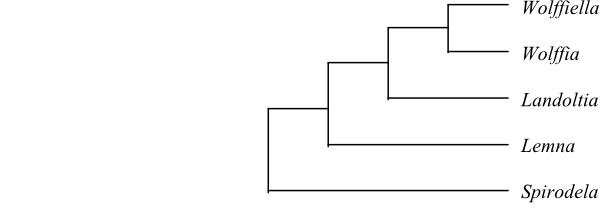

5/37. Spirodela (3; S. oligorrhiza, S. polyrrhiza, S. sichuanensis; cosmopolitan), Landoltia (1; L. punctata; southern Asia, Australia), Lemna (12; cosmopolitan), Wolffia (11; nearly cosmopolitan; paraphyletic; incl. Wolffiella?), Wolffiella (10; tropical and southern Africa, southern Asia, southeastern United States to tropical South America). – Mainly temperate and subtropical regions on the Northern Hemisphere, the Andes, Argentina, eastern and southern Africa, Madagascar, South Asia, Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand. Usually monoecious (rarely dioecious). Annual herbs. Floating, aquatic herbs with usually thalloid stems. Roots single, several or absent. Collenchyma and bundle fibres absent. Vessels absent. Venation only as primary veins. Mucilage cells present. Leaves absent. Prophyll present or absent. Spathe extremely reduced, present at side of leaf sheath, or absent. Spadix extremely reduced. Tepals absent. Stamen single, disporangiate (Wolffia and Wolffiella) or tetrasporangiate. Anther dehiscing by transversal or longitudinal slits or pores (sometimes apically). Pollen grains tricellular at dispersal. Exine ulcerate, spinulate. Pistil composed of a single carpel. Stigma infundibuliform. Placentation basal. Ovules one to seven per carpel, orthotropous, anatropous or hemianatropous, ascending, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle bistomal or endostomal. Inner integument two or three cell layers thick. Parietal tissue one (or two) cell layer thick. Nucellar cap sometimes two cell layers thick. Megagametophyte Polygonum or Allium type. Endosperm development probably cellular. Embryogenesis onagrad or irregular. Fruit an achene. Seed operculate. Endosperm starchy. Embryo undifferentiated. Hypocotyl and radicula absent. Cotyledon sheath wide, photosynthesizing. x = 10. Polyploidy and dysploidy frequently occurring. Flavonols, proanthocyanidins, alkaloids, and cyanogenic substances absent. – Lemnoideae are sister-group to the remaining Araceae (except Gymnostachys and Orontioideae). The thallus is usually interpreted as a combination of a reduced stem and a reduced leaf. The reproductive organ is interpreted as a small bisexual flower or a much reduced inflorescence with a single female flower and one or two male flowers. Spirodela is sister to the clade [Lemna+[Landoltia+[Wolffia+Wolffiella]]]. Wolffia and Wolffiella lack roots and veins on the thallus.

[[Pothoideae+Monsteroideae]+[Lasioideae+[Zamioculcadoideae s.lat.+Aroideae]]]

Araceae sensu stricto

108/3.395–3.430. According to Stevens (2001 onwards) characterized by, e.g., shoot consisting of a reiterated sympodial unit (continuation shoot); branching from the axil of a penultimate foliar organ outside the spathe; pseudopetiole distinctly differentiated from the sheathing base; spathe large and often showy; presence of peduncle; and non-multiplicative inner integument. The collenchyma is of the Type B. Seedling cataphylls may be present or absent. – The Bisexual Climbers clade is sister-group to the remainder.

The Bisexual Climbers clade (sensu Cabrera & al. 2008)

16/>1.420. Stems usually hemiepiphytic, aerial, climbing (plants sometimes terrestrial, rheophytic or helophytic). Vascular bundles often surrounded by fibres. Styloids present. H- or T-shaped trichosclereids usually present. Leaves spiral or distichous. Pseudopetiole distally geniculate. Embryo often surrounded by crystals. Separate cortical vascular bundles may occur, as well as vessels in the stem (Steven 2001 onwards). – Pothoideae are sister to Monsteroideae.

[Pothoideae+Monsteroideae]

Pothoideae Engl. in Nova Acta Acad. Caes. Leop.-Carol. German. Nat. Cur. 39: 140. 1876

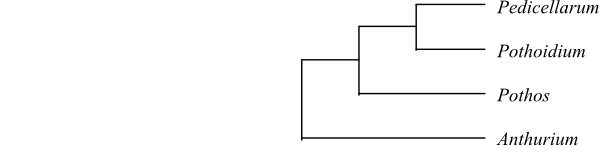

4/>1.060. Anthuriumclade Anthurium (>1.000; Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America). – Potheae Bartl., Ord. Nat. Plant.: 67. Sep 1830 [‘Pothoina’]. Pothos (c 55; Madagascar, tropical Asia to eastern Queensland, northeastern New South Wales and Melanesia), Pedicellarum (1; P. paiei; Borneo), Pothoidium (1; P. lobbianum; the Philippines, Sulawesi, the Moluccas, Orchid Island in Taiwan). – Tropical America, Madagascar, tropical Asia, northeastern Australia, Melanesia. Spadix not enclosed by the spatha. Flowers dimerous or trimerous. Anther thecae often forming a tip above anther slit. Pollen grains in Anthurium porate. Placentation basal-parietal. Ovules one or two per carpel, anatropous?, apotropous. Outer integument six to eight cell layers thick, multiplicative. Inner integument at least sometimes five to seven cell layers thick. Spatha persistent in fruit. Endosperm sparse, starchy, or absent (in Anthurium copious). Embryo sometimes with chlorophyll. n = (10) 12 (14) (15). Seedling internode sometimes long. Unifacial part of cotyledon sometimes very short. Cataphyll absent in Anthurium. – Anthurium is sister to the remaining Pothoideae, Potheae, which are characterized by shoot monopodial, endosperm sparse or absent, and x = 12.

Monsteroideae Engl. in Nova Acta Acad. Caes. Leop.-Carol. German. Nat. Cur. 39: 142. 1876

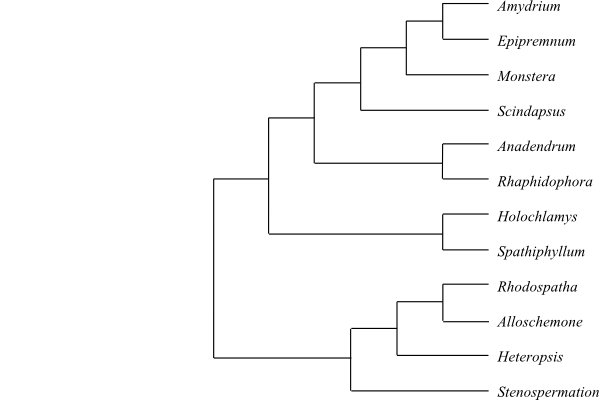

12/c 360. Heteropsideae Engl., Nat. Pflanzenr. 21: 20. 13 Jun 1905. Stenospermation (c 50; southern Mexico, Central America, tropical South America), Heteropsis (17; tropical South America), Rhodospatha (c 30; Costa Rica, Panamá, tropical South America), Alloschemone (2; A. inopinata, A. occidentalis; Brazil, Bolivia). – Spathiphylleae Engl. in Engler et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. II, 3: 112, 121. Aug 1884. Spathiphyllum (c 40; Central Malesia to Solomon Islands, Florida, southern Mexico, Central America, tropical South America), Holochlamys (1; H. beccarii; New Guinea, New Britain). – Rhaphidophoreae Engl. in Nova Acta Acad. Caes. Leop.-Carol. German. Nat. Cur. 39: 143. 1876 [‘Raphidophoreae’]. ‘Rhaphidophora’ (c 100; tropical Africa, Madagascar, tropical Asia to islands in the Pacific; paraphyletic), Anadendrum (12; southern China, Southeast Asia, Malesia to Sulawesi and the Philippines), Scindapsus (c 35; tropical Asia from India to Hainan and Solomon Islands), Monstera (c 50; southern Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America), Epipremnum (15–17; the Himalayas, southern China, Southeast Asia, Malesia to tropical Australia and islands in western Pacific), Amydrium (5; A. hainanense, A. humile, A. medium, A. sinense, A. zippelianum; southern China, Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea). – Pantropical (few species in Africa). Separate stem cortical vascular tissue sometimes present. Vessels sometimes present in stem. Laticifers sometimes present. Spatha early caducous. Flowers usually dimerous (in Spathiphylleae trimerous). Tepals often absent. Pollen grains inaperturate, expanded-monosulcate or zonate. Style often with abundant trichosclereids. Placentation often basal. Ovules one to four (to numerous) per carpel, sometimes hemianatropous. Seed often surrounded by mucilage. Endosperm usually absent (present in Spathiphylleae). Embryo often surrounded by crystals. n = 12, 14, 15, 21. Polyploidy frequently occurring. –Heteropsideae are sister-group to the remaining Monsteroideae and have x = 14. Spathiphylleae are characterized by smaller trichosclereids in bundles, and pollen grains polyplicate-multiaperturate.

[Lasioideae+[Zamioculcadoideae s.lat.+Aroideae]]

The Podolasia clade

92/1.975–2.010. Leaves usually spirally arranged. – Lasioideae are sister to the remaining Podolasia clade.

Lasioideae Engl. in Nova Acta Acad. Caes. Leop.-Carol. German. Nat. Cur. 39: 144. 1876

10/49. Dracontium (24; Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America), Dracontioides (2; D. desciscens, D. salvianii; eastern Brazil), Anaphyllopsis (3; A. americanum, A. cururuana, A. pinnata; tropical South America), Pycnospatha (2; P. arietina, P. palmata; Southeast Asia), Anaphyllum (2; A. beddomei, A. wightii; Laccadive Islands), Cyrtosperma (12; New Guinea to islands in the Pacific), Lasiomorpha (1; L. senegalensis; tropical West and Central Africa), Podolasia (1; P. stipitata; West Malesia), Lasia (2; L. concinna, L. spinosa; India, Tibet, China, Taiwan, Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea), Urospatha (11; Central America, tropical South America). – Tropical West and Central Africa, tropical Asia, Pacific islands, tropical America. Terrestrial or rooted aquatic (helophytic) plants with tuber or rhizome. Vascular bundles surrounded by fibres. Sieve tube plastids with sparse starch. Laticifers present. Pseudopetiole, abaxial surface of primary leaf veins, and peduncle very often prickly and warty. Pseudopetiole geniculate distally, with Type 4 ground tissue. Type 4 foliar spongy aerenchyma. Order of anthesis basipetal. Anther with oblique pore-like slits. Pollen grain without starch; sulcus unique among angiosperms, with ectexine lamella and thick two-layered endexine: outer layer flaky or lamellate and inner layer spongy. Pistil composed of one to three (to 16) connate carpels. Placentation of various types. Ovules one or two (to numerous) per locule, anacampylotropous, apotropous. Mesotestal and endotestal cell walls lignified. Endosperm thin or absent. Embryo curved, with chlorophyll. x = 13. – The phylogeny of Lasioideae is largely unresolved.

[Zamioculcadoideae s.lat.+Aroideae]

The Unisexual Flowers clade (sensu Cabrera & al. 2008)

82/1.925–1.960. Flowers usually unisexual (in Calla bisexual). Spatha differentiated into ‘tube’ and ‘lamina’. Spadix differentiated into zones with female flowers and male flowers, respectively. Pollen grains usually inaperturate (in Zamioculcas and Gonatopus aperturate). – This clade has weak support in molecular analyses, although the Stylochaeton clade [Stylochaeton+Zamioculcadoideae] may be sister to Aroideae.

The Stylochaeton clade (Zamioculcadoideae s.lat.)

3/26. Tropical, with the highest diversity in tropical Africa. Rhizomatous geophytes. Sterile flowers often present between female and male floral zones in inflorescence, developing in various ways. Tepals present. Stamens usually free (sometimes connate). Anthers introrse to extrorse (in Zamioculcas introrse). Pollen grains large, often with encircling sulcus. Columellae twisted, forming an ‘inner tectum’ together with outer tectum. Endexine lamellate. Intine thin. Pistil composed of two connate carpels. Placentation axile. Ovule one per carpel, ascending. Endosperm almost absent. Pistillodia present in male flowers. Ovules tenuinucellar. Micropyle bistomal. Nucellar cap and integumentary endothelium present. – Stylochaeton is sister to a clade consisting of Zamioculcas and Gonatopus.

Stylochaeton

1/20. Stylochaeton (20; central and eastern tropical Africa to Angola). – Biforines present. Leaves simple. Tepals connate. Pollen grains inaperturate. Sporopollenin ectexine very thin, undifferentiated. x = 14. – Stylochaeton resembles Zamioculcadoideae in its floral morphology. However, pollen and leaf morphology correspond well with main stream Araceae.

Zamioculcadoideae Bogner et Hesse in Aroideana 28: 13. Jul 2005

2/6. Zamioculcas (1; Z. zamiifolia; southeastern tropical Africa), Gonatopus (5; G. angustus, G. boivinii, G. clavatus, G. marattioides, G. petiolulatus; tropical East and southeastern Africa). – Kenya to northeastern South Africa. Stem condensed, thickened. Biforines absent. Leaves pinnately compound. Pseudopetiole geniculate. Pollen grains zonasulcate (extended-monosulcate). x = 17. –The pollen grains in Lasioideae, with a lamellate endexine, are relatively similar to those in Zamioculcadoideae.

Aroideae Arn., Botany: 136. 9 Mar 1832 [‘Arineae’], sensu lato

79/1.900–1.935. Tropical and subtropical regions on both hemispheres, temperate regions in Europe and eastern North America. Collenchyma usually in cortical bands or in bundle-associated strands, or absent. Laticifers usually present (simple and articulated or anastomosing; sometimes absent). Biforines often present; biforine walls thick, lignified, papillate at ends, with mucilaginous cell cytoplasm. Leaves spiral. Spatha differentiated into tube and lamina. Tepals absent. Filaments usually connate (rarely free). Anthers usually extrorse (sometimes introrse), longicidal (sometimes poricidal), with thick connectives. Pollen grains usually bicellular (sometimes tricellular) at dispersal. Exine with various sculpturing. Ectexine thin, usually without sporopollenin (consisting of polysaccharides). Endexine thick, spongy. Intine massive. Female flowers usually with staminodia. Stylodia usually free (sometimes connate). Male flowers usually with pistillodium. Placentation apical, basal or parietal. Ovules one to numerous per carpel, usually orthotropous, usually tenuinucellar (in Calla crassinucellar). Outer integument four to ten cell layers thick. Endosperm present, often starchy, or absent. Embryo sometimes chlorophyllous. Collar rhizoids sometimes present.

Callopsideae Engl. in Engler et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. Nachtr. 2: 29, 34. Apr 1906

1/1. Callopsis (1; C. volkensii; Tanzania). – Callopsis may be sister to the remaining Aroideae.

Anubiadeae Engl. in Nova Acta Acad. Caes. Leop.-Carol. German. Nat. Cur. 39: 147. 1876

1/8. Anubias (8; tropical West and Central Africa). – Aquatic or semi-aquatic herbs. Exine smooth. – Anubias may be successive sister to the remaining Aroideae except Callopsis.

Montrichardieae Engl. in Nova Acta Acad. Caes. Leop.-Carol. German. Nat. Cur. 39: 144. 1876

1/2. Montrichardia (2; M. arborescens, M. linifera; southern Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America to Peru and Brazil). – Helophytic herbs. Exine smooth. – Montrichardia may be sister to the remaining Aroideae s.lat. except Callopsideae and Anubiadeae. A fossil species, M. aquatica, has been described from Paleocene layers in Colombia.

Aroideae sensu stricto

76/1.890–1.925. Tropical and warm-temperate. Usually monoecious (sometimes dioecious; in Calla bisexual). Leaves very variable. Pollen grains inaperturate. Cotyledons sometimes nutrient storing. – Zantedeschieae are sister-group to the remainder (Philonotieae).

Zantedeschieae Engl. in Engler et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. II, 3: 113, 136. Aug 1887

24/770–775. Exine often smooth. – The basal branching of Zantedeschieae is unresolved.

The Anchomanes clade

5/36. Aglaonemateae Engl. in Nova Acta Acad. Caes. Leop.-Carol. German. Nat. Cur. 39: 148. 1876. [‘Aglaonemeae’] Aglaonema (21; tropical Asia), Aglaodorum (1; A. griffithii; West Malesia). – Nephthytideae Engl. in Engler et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. II, 3: 112, 128. Aug 1887. Nephthytis (6; N. afzelii, N. bintuluensis, N. hallaei, N. mayombensis, N. poissonii, N. swalnei; tropical West and Central Africa, one species, N. bintuluensis, on Borneo), Pseudohydrosme (2; P. buettneri, P. gabunensis; Gabon), Anchomanes (6; A. abbreviatus, A. boehmii, A. dalzielii, A. difformis, A. giganteus, A. nigritianus; tropical Africa). – Tropical Africa, tropical Asia. Foliar collenchyma usually Type Sb. Spatha boat-shaped, early caducous or marcescent. Nephthytideae are characterized by very strongly developed basal foliar ribs, having dracontioid lobing.

Homalomeneae (Schott) M. Hotta in Mem. Fac. Sci. Kyoto Univ., ser. Biol., 4: 89. 1970

5/645–650. Culcasieae Engl. in Engler et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. II, 3: 112, 116. Aug 1887. Culcasia (27; tropical Africa), Cercestis (10; tropical West and Central Africa). – Philodendreae Schott, Syn. Aroid.: 71. Mar 1856. Philodendron (c 490; Florida, southern Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America), Adelonema (16; tropical America), Homalomena (100–105; tropical Asia, tropical America). – Pantropical. Roots with sclerotic hypodermis and resin canals. Anthers usually without endothecial thickenings (present in Homalomena). – Culcasieae are hemiepiphytic climbing plants. Philodendreae are characterized by female-sterile-male spadix floral zonation. Thaumatophyllum (tropical South America; in Philodendron s.l.) is sometimes recovered as sister-group to Philodendron s.str. (Vasconcelos & al. 2018, Sakuragui & al. 2018).

The Zantedeschia clade sensu stricto

14/88–90. Zantedeschiaclade Zantedeschia (8; eastern tropical and southern Africa). – Spathicarpeae Schott, Syn. Aroid.: 214. Mar 1856. Lorenzia (1; L. umbrosa; Amapá in northern Brazil), Bognera (1; B. recondita; Brazil), Gearum (1; G. brasiliense; central Brazil), Dieffenbachia (c 55; southern Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America), Mangonia (2; M. tweedieana, M. uruguaya; Brazil, Uruguay), Incarum (1; I. pavonii; Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia), Gorgonidium (8; Peru, Bolivia, northern Argentina), Spathantheum (2; S. fallax, S. orbignyanum; the Andes in Peru, Bolivia and northern Argentina), Synandrospadix (1; S. vermitoxicus; Bolivia, northern Argentina), Croatiella (1; C. integrifolium; Ecuador), Spathicarpa (3; S. gardneri, S. hastifolia, S. lanceolata; southern tropical South America), Taccarum (6; T. caudatum, T. crassispathum, T peregrinum, T. ulei, T. warmingii, T. weddellianum; tropical South America), Asterostigma (8; Brazil). – Tropical and southern Africa, tropical America. Spathicarpeae are characterized by connate stamens and x = 17.

Philonotieae S. Y. Wong et P. C. Boyce in S. Y. Wong et al., Taxon 59: 121. 5 Feb 2010

52/1.120–1.150. Calla is sometimes recovered as sister to the Dracunculus clade, although with weak support (Cusimano & al. 2011), and sometimes as sister to the clade [Rheophytes clade+Dracunculeae] (Henriquez & al. 2014).

Calleae Bartl., Ord. Nat. Plant.: 67. Sep 1830 [‘Callea’]

1/1. Calla

(C. palustris; temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere). –

Rooted helophytic herb. Bisexual. Vascular bundles amphivasal. Simple

articulated laticifers present. Biforines absent. Leaves distichous. Leaf

sheath elongate, ligulate. Tepals absent. Pollen grains diporate. Pistil

composed of a single carpel. Placentation basal. Ovules six to nine per carpel,

crassinucellar. Endosperm present. Embryo with chlorophyll. Seedling roots with

chlorophyll. n = 18, 27. – The bisexual flowers are remarkable, yet may be

due to a reversal.

The Rheophytes clade

(sensu Cabrera & al. 2008)

15/255–265. Philonotion clade Philonotion (1; P. spruceanum; northernmost South America). – Cryptocoryneae Blume, Rumphia 1: 83. Jul-Nov 1836. Lagenandra (15; southern India, Sri Lanka, Assam, Bangladesh), Cryptocoryne (65; India and Sri Lanka to southern China and Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea). – Schismatoglottideae Nakai, Chosakuronbun Mokuroku [Ord. Fam. Trib. Nov.]: 218. 20 Jul 1943. Piptospatha (12; peninsular Thailand, the Malay Peninsula, Borneo), Ooia (2; O. grabowskii, O. kinabaluensis; Borneo), Pichinia (1; P. disticha; Sarawak), Schottarum (2; S. josefii, S. sarikeensis; Kanowit-Song-Ai area in Sarawak), Phymatarum (1; P. borneense; Borneo), Schismatoglottis (100–110; southern China, Southeast Asia, Malesia to Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, Taiwan, with their highest diversity on Borneo), Aridarum (10; Borneo), Schottariella (1; S. mirifica; Borneo), Bucephalandra (30; Borneo), Bakoa (1; B. lucens; Sarawak), Apoballis (12; Thailand, West Malesia, Timor), Hestia (1; H. longifolia; Sarawak). – Northernmost South America, tropical Asia, with their highest diversity on Borneo. Mainly aquatics and rheophytes. Anthers with horned thecae. Exine often smooth. – The Rheophytes clade corresponds to Schismatoglottideae sensu lato, with the addition of Philonotion. Cryptocoryneae are characterized by absence of laticifers, foliar Type Sv collenchyma, presence of squamulae intravaginales, spatha and spadix forming two chambers by partial fusion, spatha with internal flap and connate margins, and n = 18. Schismatoglottideae have erect aerial stems, early caducous or marcescent upper pseudolamina, leaf sheath with long ligules at apex, and spatha with persistent basal half.

Dracunculeae Schott in Schott et Endlicher, Melet. Bot.: 16. 1832 [‘Dracunculinae’]

36/865–885. Foliar collenchyma Type Sv. Sympodial inframarginal vein usually present on each side of pseudolamina. Exine usually spinulate. Stamens often more or less connate into a synandrium. – Amorphophalleae are sister-group to the remaining Dracunculeae.

Amorphophalleae Engl. in Nova Acta Acad. Caes. Leop.-Carol. German. Nat. Cur. 39: 144. 1876

12/c 410. Thomsonieae Blume in Rumphia 1: 138. Apr-Jun 1837. Amorphophallus (c 200; tropical regions in the Old World). – Caladieae Schott in Schott et Endlicher, Melet. Bot.: 18. 1832. Jasarum (1; J. steyermarkii; Venezuela, Guyana), Hapaline (8; Burma to Borneo), Caladium (14; Costa Rica, Panamá, tropical South America), Syngonium (c 35; Florida, Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical ), Filarum (1; F. manserichense; Peru), Ulearum (2; U. donburnsii, U. sagittatum; Amazonia in Brazil), Xanthosoma (c 75; Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America), Chlorospatha (c 70; Costa Rica, Panamá, tropical South America, with the largest diversity in the northwestern Andes), Scaphispatha (1; S. gracilis; Bolivia), Zomicarpella (2; Z. amazonica: northwestern Brazil; Z. maculata: Colombia, Peru), Zomicarpa (2; Z. pythonium, Z. steigeriana; northeastern Brazil). – Pantropical. Thomsonieae have tripartite primary leaf development with decompound subdivision, involute ptyxis, often no sterile zone between the male and female zones, and presence of smooth or staminodial spadix appendix. Caladieae are characterized by anastomosing laticifers, persistent spathe tube, and early caducous or marcescent spathe lamina.

Ambrosineae Schott in Schott et Endlicher, Melet. Bot.: 16. 1832 [‘Ambrosinieae’]

24/455–475. The Colletogyne clade is sister to Pistieae.

The Colletogyne clade

7/19. Arisareae Dumort., Fl. Belg.: 162. 1827. Arisarum (3; A. proboscideum, A. simorrhinum, A. vulgare; Macaronesia except Cape Verde Islands, the Mediterranean to the Caucasus), Ambrosina (1; A. bassii; central Mediterranean). – Typhonodoreae Engl. in Nova Acta Acad. Caes. Leop.-Carol. German. Nat. Cur. 39: 146. 1876. Peltandrinae Schott, Syn. Aroid.: 50. Mar 1856. Peltandra (2; P. sagittifolia: southeastern United States; P. virginica: southeastern Canada, eastern and southeastern United States, Cuba), Typhonodorum (1; T. lindleyanum; coastal regions in East Africa, Madagascar, the Mascarene Islands). – Arophyteae A. Lemee ex Bogner in Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 92: 9. 1972. Arophyton (7; A. buchetii, A. crassifolium, A. humbertii, A. pedatum, A. rhizomatosum, A. simplex, A. tripartitum; Madagascar), Carlephyton (3; C. diegonse, C. glaucophyllum, C. madagascariense; northern Madagascar), Colletogyne (1; C. perrieri; Madagascar). – The Mediterranean to the Caucasus, Macaronesia, East Africa, Madagascar, the Mascarene Islands, North America. Arisareae are characterized by striate exine, connate spathe margin, and adnation of the spadix female zone to spathe. Typhonodoreae have staminodia in female zone, endosperm sparse to absent, embryo large, and cotyledon nutrient-storing. Peltandrinae are helophytes with parallel-pinnate fine venation, spathae with a persistent tube and caducous or marcescent lamina, female-sterile-male-sterile zonation of spadix, staminodial spadix appendices, and entirely connate stamens. Arophyteae, in Madagascar, have female-male zonation of spadix, connate stamens, globose pollen grains, and spinulate exine.

Pistieae Lecoq et Juill., Dict. Rais. Term. Bot.: 56, 493. 1831 [‘Pistiaceae’]

17/435–440. Protarumclade Protarum (1; P. sechellarum; the Seychelles). – Pistia clade Pistia (1; P. stratiotes; tropical East Africa?). – Colocasieae Brongn., Enum. Plant. Mus. Paris: 13. 12 Aug 1843. Ariopsis (2; A. peltata: Western Ghats, Sikkim, Assam; A. protanthera: Bhutan, Burma), Steudnera (8; the Himalayas, Southeast Asia to the Malay Peninsula), Remusatia (4; R. hookerana, R. pumila, R. vivipara, R. yunnanensis; tropical Africa, Madagascar, India, Sri Lanka, the Himalayas, Tibet, Burma, southern China, Southeast Asia, Malesia to tropical Australia, Taiwan and islands in the Pacific), Colocasia (10; the Himalayas, Tibet, Burma, southern China, Southeast Asia, the Nicobar Islands, West Malesia). – Englerarum (1; E. hypnosum; southwestern Yunnan, Laos, Thailand). – Alocasiinae Schott, Syn. Aroid.: 43. Mar 1856 [‘Alocasinae’]. Alocasia (c 80; the Hmalayas and southeastern China to Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea and tropical Australia); Arisaema (180–185; eastern Africa, southern Arabian Peninsula, India, the Himalayas, Tibet, East and tropical Asia to New Guinea, southeastern Canada, eastern and southeastern United States, Mexico); Pinellia (9; China, the Korean Peninsula, Japan, the Ryukyu Islands). – Areae Theriophonum (7; T. dalzellii, T. danielii, T. fischeri, T. infaustum, T. manickamii, T. minutum, T. sivaganganum; central and southern India, Sri Lanka), Typhonium (c 70; Mongolia, China, tropical Asia to New Guinea and tropical Australia, Taiwan), Eminium (9; eastern Mediterranean to Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia), Biarum (21; the Mediterranean from Morocco to Syria and Egypt), Arum (c 30; Europe, the Mediterranean to Iran and the Himalayas), Dracunculus (3; D. canariensis: the Canary Islands, Madeira; D. muscivorus: Corsica, Sardinia, the Balearic Islands; D. vulgaris: central and eastern Mediterranean). – Europe, Macaronesia, the Mediterranean, tropical Africa, Madagascar, the Arabian Peninsula, western and Central Asia, East and tropical Asia to tropical Asia and islands in the Pacific, eastern North America. Pistia has exostomal ovules. Colocasieae have peltate leaves, usually anastomosing laticifers, colocasioid fine leaf venation, and entirely connate stamens. Areae are a subclade within the clade Alocasiinae and are characterized by reticulate fine leaf venation, usually smooth spadix appendices, spinulate exine, bristle- or hair-like staminodia (together with Arisaema), and orthotropous ovules.

|

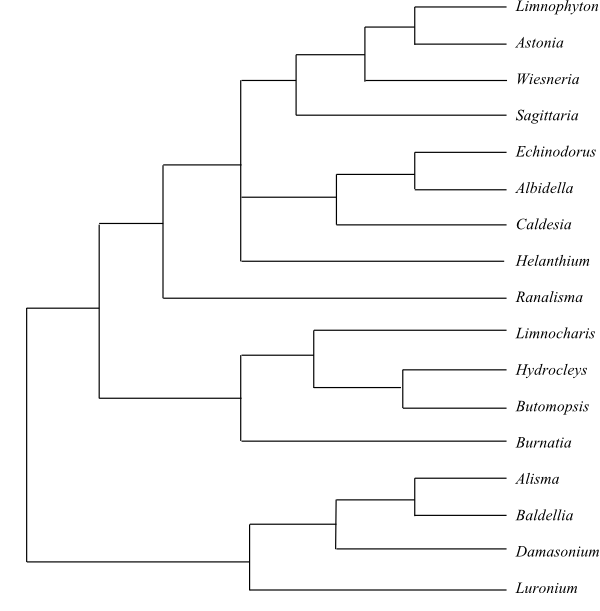

Bayesian summary tree of Araceae based on DNA sequence data (Cabrera & al. 2008). Gymnostachys is identified in some other analyses as sister to the remaining Araceae. In many analyses Lasioideae are sister-group to the Zamioculcadoideae clade plus the rest; this alternative is followed in the text above. |

|

Bayesian summary tree of Orontioideae based on DNA sequence data (Cabrera & al. 2008). |

|

Bayesian summary tree of Lemnoideae based on DNA sequence data (Rothwell & al. 2004; Cabrera & al. 2008). |

|

Bayesian summary tree of Pothoideae based on DNA sequence data (Cabrera & al. 2008). |

|

Bayesian summary tree of Monsteroideae based on DNA sequence data (Cabrera & al. 2008). |

|

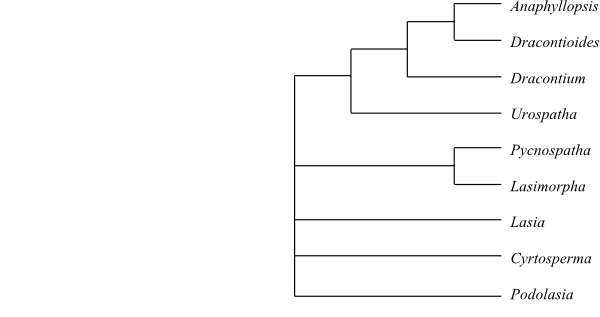

Bayesian summary tree of Lasioideae based on DNA sequence data (Cabrera & al. 2008). |

|

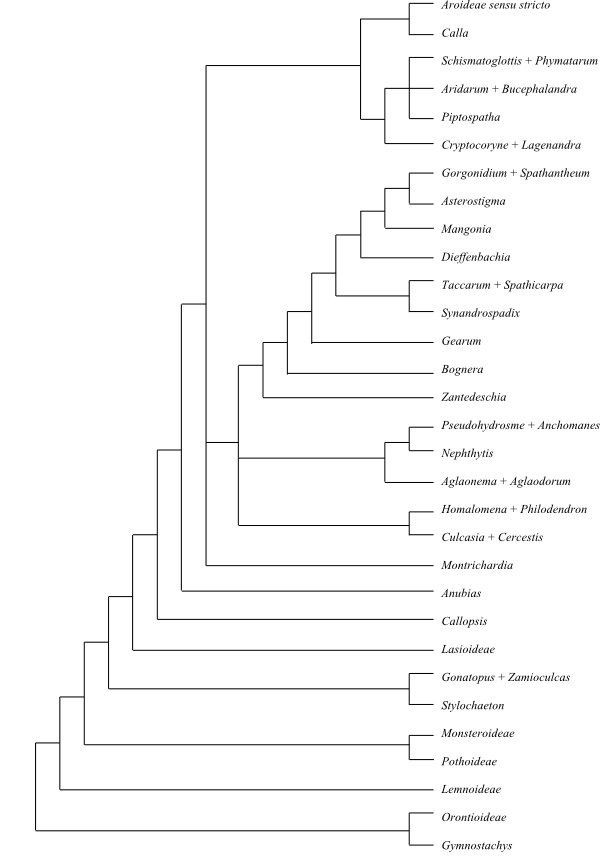

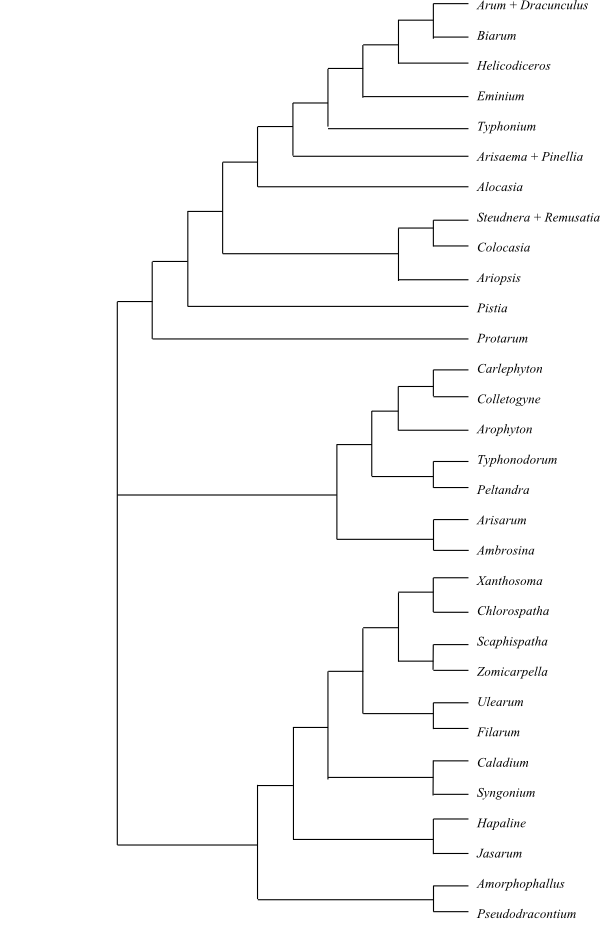

Bayesian summary tree of Aroideae sensu stricto based on DNA sequence data (Cabrera & al. 2008). |

BUTOMACEAE Mirb. |

( Back to Alismatales ) |

Butomineae Engl., Syllabus, ed. 2: 73. Mai 1898; Butomales Rich. in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp. Regn. Veg.: 8. Sep-Oct 1835 [‘Butomeae’]; Butomanae Takht. ex Reveal in Novon 2: 235. 13 Oct 1992

Genera/species 1/1

Distribution Temperate regions in Eurasia and North Africa.

Fossils Seeds that may be attributed to Butomaceae have been described from the Oligocene onwards in Europe.

Habit Bisexual, perennial herb. Aquatic or helophytic. Axillary buds sometimes developing into short-stalked bulbils. Rhizome starchy and with monopodial branching.

Vegetative anatomy Roots sometimes contractile. Phellogen absent. Secondary lateral growth absent. Endodermis absent. Vessels present in roots. Vessel elements with usually simple (sometimes scalariform) perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystalloid bodies, without starch or protein filaments. Nodes multilacunar with several leaf traces. Schizogenous secretory canals absent; laticifers absent. Outer part of rhizome cortex with crystals as irregular polygonal groups or single styloids.

Trichomes Hairs absent.

Leaves Alternate (distichous), simple, entire, linear, triangular in cross-section, not differentiated into pseudopetiole and pseudolamina, with ? ptyxis. Stipules absent; leaf sheath well developed. Leaf base with a row of intravaginal hairlike scales, squamulae intravaginales. Venation parallelodromous. Stomata paracytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids non-orientated. Schizogenous secretory canals and cavities. Mesophyll cells often with calciumoxalate crystals. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal, umbel-like, cymose, on a long peduncle (scape) from rhizome, subtended by usually three (sometimes two or four) spathe-like bracts. Floral bracts sometimes absent.

Flowers Actinomorphic. Hypogyny. Tepals 3+3, free; outer tepals petaloid-sepaloid, with imbricate aestivation; inner tepals petaloid, crumpled in bud, caducous. Gynoecial-septal nectaries present on lateral walls of carpel bases. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens 6+3 (outer stamens paired, bifid?, alternipetalous, alternating with inner stamens). Filaments flat, free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, latrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Corolla/androecium-primordia with one pair of stamens probably first differentiating and subsequently one adaxial stamen. Tapetum amoeboid-periplasmodial, with uninucleate cells. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains monosulcate, shed as monads, tricellular at dispersal. Exine semitectate, with columellate infratectum, reticulate, smooth.

Gynoecium Carpels six, in one whorl, usually at best postgenitally fused; carpel plicate or conduplicate, incompletely closed at apex (carpellary margins held together distally by interwoven hairs). Stylodia very short. Stigmatic surfaces ventral, more or less decurrent, bilobate, papillate, Dry type. Pistillodia absent.

Ovules Placentation laminar-diffuse (lateral, ovules scattered over carpellary surface); placentae covered with secretions. Ovules c. 20 to more than 100 per carpel, anatropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle ?-stomal. Outer integument ? cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Parietal cell formed from archesporial cell. Parietal tissue one cell layer thick. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Synergids with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells not proliferating. Endosperm development helobial. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis caryophyllad.

Fruit An assemblage of follicles.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat testal-tegmic. Exotesta with thickened epidermal cell walls and with incrustations. Endotesta? Tegmen persistent. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm absent. Embryo large, straight, well differentiated, starchy, without chlorophyll. Cotyledon one. Cotyledon hyperphyll elongate, assimilating. Hypocotyl internode long. Coleoptile absent. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = (7) 8, 10–15, 20, 21 – Triploid individuals with 2n = 39 are frequent in Europe. Chromosomes 3,7–8,3 μm long.

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavone-C-glycosides present. Flavonols, ellagic acid, proanthocyanidins, alkaloids, saponins, and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Ornamental plants, starch source (locally).

Systematics Butomus (1; B. umbellatus; temperate regions in Europe, northern Africa and Asia east to Manchuria and eastern China).

Butomus is sister to Hydrocharitaceae.

CYMODOCEACEAE Vines |

( Back to Alismatales ) |

Cymodoceales Nakai, Chosakuronbun Mokuroku [Ord. Fam. Trib. Nov.]: 211. 20 Jul 1943

Genera/species 5/16

Distribution Mainly tropical and subtropical coastal marine areas; some species in warm-temperate seas along coasts of Australia and the Mediterranean.

Fossils Thalassocharis was described from the late Cretaceous in the Netherlands, and Thalassodendron auricula-leporis from the Mid-Eocene of Florida, USA. These may be assigned to Cymodoceaceae. Furthermore, Cymodocea is known from several Cenozoic fossils.

Habit Monoecious or dioecious, perennial herbs. Marine. Submersed. Rhizome in Cymodocea, Halodule and Syringodium herbaceous, monopodially branched, in Amphibolis and Thalassodendron lignified, sympodially branched.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza absent. Roots often with bacterial colonies (nitrogen-fixing?). Epidermal cells of roots usually lignified. Phellogen absent. Endodermal and some outer-cortical and epidermal cell walls of rhizome lignified. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels absent (also in roots). Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve elements in Halodule with thick nacreous cell walls (absent from roots). Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystalloid bodies, without starch or protein filaments. Nodes? Tanniniferous cells abundant. Calciumoxalate crystals absent.

Trichomes Hairs absent.

Leaves Alternate (distichous), simple, entire, linear to terete, with ? ptyxis. Stipules absent; leaf sheath well developed, with basal membranous sheath-like ligule in transition zone to lamina; axillary intravaginal scales, squamulae intravaginales, two or more. Venation parallelodromous; primary veins connected by transversal veins. Stomata absent. Cuticular wax absent. Mesophyll without calciumoxalate crystals. Epidermis with tanniniferous cells. Leaf margin subentire, at apex finely serrate.

Inflorescence Flowers axillary, usually solitary (in Syringodium in few-flowered cymose inflorescences), surrounded by a spatha (bract).

Flowers Zygomorphic?, small. Tepals absent? (in Amphibolis transformed into an attachment organ). Nectary absent. Disc absent.