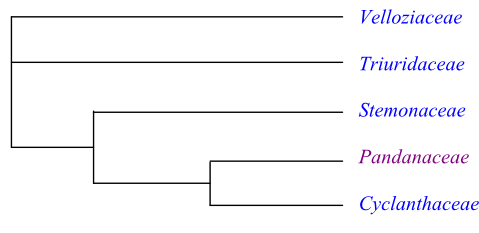

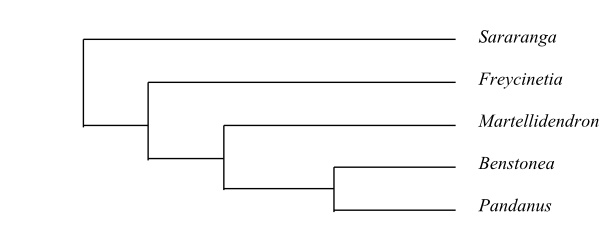

Phylogeny of Pandanales based on DNA sequence data. Triuridaceae are sister-group to the clade [Stemonaceae+[Pandanaceae+Cyclanthaceae]], according to Mennes & al. (2013).

Pandanopsida Brongn., Enum. Plant. Mus. Paris: xv, 14. 12 Aug 1843 [’Pandanoideae’]

Habit Bisexual, monoecious, dioecious or polygamodioecious, trees, shrubs, suffrutices or lianas (rarely epiphytes). Sometimes achlorophyllous mycoheterotrophs.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio subepidermal or outer-cortical, or absent. Stem vascular bundles collateral or bipolar, or stem cylinder consisting of narrow bundles. Secondary lateral growth usually absent. Vessels present in root, stem and leaves, or absent. Vessel elements usually with scalariform (rarely simple) perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays absent? Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c or P2cf types. Nodes multilacunar with several leaf traces. Secretory mucilage ducts often present. Laticifers or tanniniferous cells rarely present. Silica bodies absent. Calciumoxalate as druses, raphides, styloids, crystal sand or solitary prismatic or rhomboidal crystals.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate or multiseriate, simple or branched (stellate, fasciculate, etc.), or absent; multicellular glandular hairs rarely present.

Leaves Alternate (usually tristichous, sometimes distichous, rarely tetrastichous), simple, palmately lobed or entire, linear, with conduplicate, plicate or flat ptyxis (often M-shaped in cross-section). Stipules absent; leaf sheath well developed, open or closed, or absent. Venation parallelodromous or consisting of one vascular strand. Stomata tetracytic, anomocytic, (twice) paracytic, or cyclocytic (sometimes absent). Cuticular wax crystalloids as longitudinally parallel or aggregated rodlets (Strelitzia type) or non-oriented platelets, or amorphous. Mesophyll with schizogenous or lysigenous cavities; mesophyll with mucilaginous cells and canals containing calciumoxalate as raphides, druses, styloids or single prismatic crystals. Leaf margin entire or serrate-dentate (sometimes spinulose).

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, raceme- or spadix-like, simple or compound, spike-like in compound raceme- or umbel-like cymose inflorescence, sometimes raceme, spike, panicle, or thyrse with flowers in spirals or whorls (inflorescence then surrounded by one or several usually petaloid spathae), or flowers solitary. Floral prophyll (bracteole) sometimes absent.

Flowers Usually actinomorphic (sometimes asymmetrical, rarely slightly zygomorphic). Hypanthium sometimes present. Hypogyny, epigyny or half epigyny. Tepals three to c. 30, with imbricate or valvate aestivation, usually sepaloid (sometimes petaloid), free or more or less connate, in one or two whorls, or strongly reduced or absent. Nectary usually absent (septal nectaries sometimes present). Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens (two or) three to more than 300 (delimitation of single flowers sometimes indistinct). Filaments simple or branched, free from each other or more or less connate, usually free from tepals (rarely adnate to tepal bases or absent). Anthers usually basifixed (sometimes dorsifixed), non-versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (sometimes disporangiate or trisporangiate), introrse, extrorse or latrorse, usually longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum usually secretory (sometimes amoeboid-periplasmodial). Female flowers often with staminodia.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains monoporate, monosulcate, monosulcoidate, monoulcerate or monoulceroidate (sometimes inaperturate, rarely disulcate), usually shed as monads (rarely dyads or tetrads), usually bicellular (sometimes tricellular) at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate (sometimes intectate), with columellate infratectum, microreticulate, reticulate, rugate, foveolate, spinulate, verrucate, verruculate, granulate, gemmate, psilate or smooth.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of one to more than 70 usually more or less connate carpels; carpels often incompletely closed. Ovary superior, inferior or semi-inferior, unilocular to multilocular. Style single, simple, short, or stylodia four, free or connate at base, or absent. Stigma capitate, clavate, reniform, hippocrepomorphic or lobate (rarely elongate), ventral or dorsal in unicarpellate pistils, centrifugal or centripetal in multicarpellate pistils, or stigmas four, laterally flattened, wide, papillate or non-papillate, Dry or Wet type. Pistillodium usually absent (male flowers sometimes with pistillodium).

Ovules Placentation parietal, apical, axile, subbasal or basal. Ovules one to more than 150 per carpel, anatropous or hemianatropous, ascending or horizontal, apotropous or epitropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar to incompletely tenuinucellar. Micropyle endostomal or bistomal. Funicular obturator sometimes present. Parietal cell formed from archesporial cell, or absent. Nucellar cap sometimes formed. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type, disporous, Allium type, or tetrasporous, Fritillaria type). Synergids sometimes with a filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells three, 64 to more than 200, due to immigration of nuclei from megasporangium, persistent, often proliferating. Endosperm development nuclear or helobial. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis at least sometimes asterad.

Fruit A loculicidal or poricidal capsule, a berry (often connate and adnate to receptacle into a compound fruit; sometimes with fibres or crystals in pericarp) or a drupe with fibre strands in pericarp, sometimes entirely or partially fusing with each other and with inflorescence receptacle into syncarps (sometimes an assemblage of achenes or a multifolliculus, rarely a pyxidium or an explosively dehiscing capsule). Pericarp sometimes rich in oils.

Seeds Aril absent. Strophiole sometimes developed from raphe. Elaiosome sometimes present. Exotestal cells often thick- or thin-walled. Endotesta sometimes palisade. Tegmen persistent and well developed, crushed or absent. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, proteinaceous and oily or starchy (sometimes ruminate). Embryo small to minute, straight, well differentiated or rudimentary, chlorophyll? Cotyledon one, not photosynthesizing. Hypocotyl internode long or absent. Cotyledon hyperphyll compact, not assimilating. Coleoptile absent. Collar rhizoids often present. Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology x = 7–9, 11, 12, 15–17, 19, 24, 25, 28, 30

DNA Deletion of 6 bp in atpA in most investigated taxa.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), O-methylated, C-methylated and prenylated lipophilic flavonoids, flavone-C-glycosides, resins of oxidized tetracyclic and pentacyclic diterpenes and triterpenes, tannins, caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, piperidine alkaloids, lactone alkaloids (tuberostemonine), steroidal saponins, and cyanogenic compounds present. Phlobaphene sometimes present in testal epidermis. Ellagic acid, proanthocyanidins, and quinones not found.

Systematics Pandanales are sister-group to Taccales. The basal branching of Pandanales is unresolved, and Velloziaceae, Triuridaceae and a clade consisting of Stemonaceae, Pandanaceae and Cyclanthaceae together form a trichotomy. There is weak support for Triuridaceae being sister to [Stemonaceae+[Pandanaceae+Cyclanthaceae]]. Nectaries are absent in at least the last three clades and probably also in Triuridaceae.

Steven (2001 onwards) lists flowers not trimerous; style absent; and placentation parietal as potential synapomorphies of the clade [Stemonaceae+ [Pandanaceae+Cyclanthaceae]]. The clade [Pandanaceae+Cyclanthaceae] is characterized by, e.g., the following features: stem vascular bundles compound; leaves plicate when mature; stomata tetracytic, the subsidiary cells of which having oblique divisions; inflorescence a spadix with densely spaced (congested) sessile unisexual flowers and large inflorescence bracts; stamens usually several to numerous; female flowers with staminodia; pollen grains porate; styloids present; male flowers with pistillodium; ovules apotropous, with radiating subepidermal megasporangial/chalazal cells; fruit a baccate or drupaceous syncarp; endotesta well developed, with two persistent inner cuticular layers; cotyledon not photosynthesizing; and all seedling internodes prolonged.

|

Phylogeny of Pandanales based on DNA sequence data. Triuridaceae are sister-group to the clade [Stemonaceae+[Pandanaceae+Cyclanthaceae]], according to Mennes & al. (2013). |

CYCLANTHACEAE Poit. ex A. Rich. |

( Back to Pandanales ) |

Cyclanthales Poit. in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp. Regn. Veg.: 6. Sep-Oct 1835 [‘Cyclantheae’]; Cyclanthineae J. Presl in Nowočeská Bibl. [Wšobecný Rostl.] 7: 1655, 1666. 1846 [‘Cyclantheae’]; Cyclanthanae Thorne ex Reveal in Phytologia 79: 71. 29 Apr 1996

Genera/species 12/230–235

Distribution Central and tropical South America, the West Indies.

Fossils Fossil infructescences with seeds have been found in Eocene layers in Germany and England and are assigned to Cyclanthus. Cyclanthus messelensis comprises flowers and seeds of Cyclanthaceae from the mid-Eocene of Germany.

Habit Monoecious, perennial herbs, suffrutices or lianas. Some species are epiphytes.

Vegetative anatomy Root cortex with air cavities. Phellogen ab initio subepidermal or outer-cortical (Carludovicoideae; absent in Cyclanthus); cortex with a girdle of subepidermal sclereids (Cyclanthus). Central vascular cylinder with simple, collateral or amphivasal, peripheral or compound, diffuse vascular bundles with delimited simple bundles of separate xylem and phloem surrounded by a common envelope. Secondary lateral growth absent. Tracheids (’vessel tracheids’) or vessels present in root and leaves. Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays? Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals. Nodes? Secretory mucilage canals present in vegetative organs in most genera (absent in Cyclanthus). Vessels in Cyclanthus with inarticulated laticifers with white or colourless latex. Tanniniferous cells usually frequent (absent in Cyclanthus). Silica bodies absent. Calciumoxalate as druses, raphides or styloids (in styloid sacs, in Evodianthus and Dianthoveus arranged in all directions), or single crystals or crystal sand.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate or multiseriate.

Leaves Alternate (usually spirotristichous, rarely distichous), simple, usually shallowly to deeply bilobed (sometimes divided and flabelliform; in Carludovica quadrilobate; in Ludovia entire), differentiated into pseudopetiole and pseudolamina, with plicate (in Carludovicoideae) or modified plicate (unique type, in Cyclanthus) ptyxis. Stipules absent; leaf sheath well developed, open. Petiole vascular bundles, fibre bundles, numerous and scattered, peripheral; pseudopetiole in Cyclanthus with air canals V-shaped in cross-section. Venation parallelodromous (often seemingly palmate), with one or three primary veins. Stomata tetracytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids as longitudinally aggregated rodlets (Strelitzia type) or absent. Mesophyll usually with schizogenous (in Cyclanthus lysigenous) cavities; mesophyll with mucilaginous cells containing calciumoxalate as raphides, druses, styloids or single prismatic crystals. Leaf margin serrate or deeply divided.

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, simple, spadix-like (spadiciform), ab initio enclosed by (two or) three or four (to eleven), sometimes petaloid, usually caducous bracts, spathae, usually with male and female flowers alternating in spirally arranged dense partial inflorescences, thyrses, in which each female flower is sourrounded by four male flowers. In Cyclanthus alternating whorls (rarely partially spirals) of female and male flowers; individual flowers indistinctly delimited and usually entirely connate. Inflorescence in Cyclanthus with mucilaginous canals and laticifers (absent in Carludovicoideae).

Flowers Actinomorphic or asymmetrical, small. Usually epigyny or half epigyny (in a few species of Sphaeradenia and Stelestylis hypogyny). Tepals often with single abaxial glands; tepals in male flowers of Carludovicoideae six to c. 30, with imbricate aestivation, sepaloid, reduced, usually in one whorl (rarely in two whorls or absent); tepals in female flowers of Carludovicoideae four, sepaloid, fleshy, often persistent and accrescent in fruit, free or connate at base (rarely reduced). Male flowers in Cyclanthus as linear rows (usually four rows in each whorl) of stamens; female flowers in Cyclanthus as two rows of strongly reduced sepaloid tepals, two rows of staminodia and two rows of pistils with ovaries connate into a common cavity. Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens less than ten to more than 150. Filaments usually swollen at base and connate, free from tepals (rarely absent). Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, latrorse, usually longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits; in Dicranopygium mirabile a two-phase dehiscence occurs in which rupture of inner anther wall layer is delayed), sometimes with an apical secreting gland. Tapetum secretory, with binucleate to at least quadrinucleate cells. Female flowers usually with four long, filiform, antetepalous staminodia, usually adnate at base to tepals (staminodia reduced in Cyclanthus).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains usually monosulcate or monosulcoidate to monoulcerate or monoulceroidate (in Carludovica monoporate with a distal furrow; in Evodianthus and Dianthoveus inaperturate; in Thoracocarpus disulcate/biforaminate), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum, usually foveolate (in Evodianthus and Dianthoveus psilate).

Gynoecium Pistil composed of four connate usually alternitepalous carpels. Ovary usually inferior or semi-inferior (rarely superior), unilocular (ovaries in Cyclanthus connate in whorls forming a common cavity). Stylodia four, free or more or less connate at base, usually persistent, or absent. Stigmas four, alternitepalous, laterally more or less flattened, wide, sometimes fleshy, usually persistent, papillate, Wet type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation usually parietal (rarely apical or subapical). Ovules c. 50 to more than 150 per carpel, anatropous, apotropous or epitropous, bitegmic, tenuinucellar to pseudocrassinucellar (not in Cyclanthus) or crassinucellar. Micropyle bistomal. Outer integument three to five cell layers thick. Inner integument two cell layers thick. Hypostase sometimes present. Parietal cell not formed (parietal tissue absent). Nucellar cap, in Carludovicoideae two or three cell layers thick (absent in Cyclanthus), formed by periclinal cell divisions in megasporangial epidermis. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development helobial. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit In Carludovicoideae berries, usually more or less connate and adnate to floral receptacle into a berry-like compound fruit, often lignified in upper part, usually with persistent and accrescent tepals, styles and stigmas (in some genera a fleshy pyxidium, rarely an explosively dehiscing capsule). Ovaries in Cyclanthus connate into dry hollow whorls filled with seeds surrounded by mucilage, each inflorescence whorl forming a compound fruit.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed in Stelestylis with long apical wing-like process. Seed coat testal. Exotestal cells thin-walled, undifferentiated, or thick-walled. Endotesta sometimes a palisade layer. Tegmen usually collapsed (exotegmen sometimes persistent). Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, fleshy, horny, fatty, proteinaceous and with aleurone (sometimes ruminate; in Dicranopygium also with starch). Embryo usually small, straight (rarely curved), well differentiated, often with calciumoxalate raphides (embryo in Dicranopygium starchy), chlorophyll? Cotyledon one, little differentiated, not photosynthesizing. Cotyledon hyperphyll compact, not assimilating. Hypocotyl internode absent. Coleoptile absent (lobes of cotyledon leaf sheath distinct). Collar rhizoids present. Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar.

Cytology n = 9 (Cyclanthus); n = 9, 15, 16 (Carludovicoideae)

DNA

Phytochemistry Unsufficiently known. Polyphenols, (steroidal?) saponins, p-coumaric acid, and cyanogenic compounds present. Ellagic acid, proanthocyanidins, and alkaloids not found.

Use Ornamental plants, textile plants, carpets, Panama hats (toquilla from Carludovica palmata), thatching, basketry, handicraft, medicinal plants (Asplundia).

Systematics

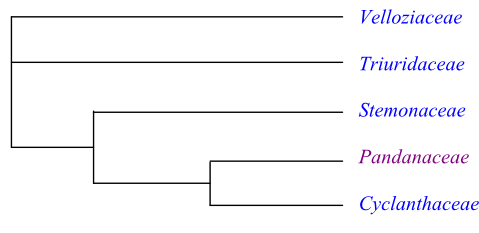

Cyclanthaceae are sister-group to Pandanaceae. Cyclanthus is sister to the remaining Cyclanthaceae. There is no molecular phylogeny available.

Cyclanthoideae Burnett, Outline Bot.: 405. Feb 1835 [’Cyclanthidae’]

1/1. Cyclanthus (1; C. bipartitus; Central America, the Lesser Antilles, northern South America). – Laticifers inarticulated. Lysigenous air spaces with transversal septa. Subepidermal sclereids present. Leaves bifid, with two veins. Inflorescence with whorls of male and female “flowers”. Tepals absent. Stamens in four rows per whorl, connate at base. Ovary locules with densely spaced placentae. Nucellar cap absent. Funicle long. Fruit dry, compound, dehiscing along middle of carpellary annulus. Seeds embedded in mucilage. Endotestal cells palisade, with granular inner periclinal walls.

Carludovicoideae (Drude) Harling in Acta Hort. Berg. 18: 126. 1958

11/230–235. Carludovica (4; C. drudei, C. palmata, C. rotundifolia, C. sulcata; southern Mexico, Central America, tropical South America), Evodianthus (1; E. funifer; Central America, northern tropical South America), Dianthoveus (1; D. cremnophilus; southwestern Colombia, northern Ecuador), Asplundia (c 100; Central America, the West Indies, tropical South America), Thoracocarpus (1; T. bissectus; tropical South America), Dicranopygium (c 55; southern Mexico, Central America, tropical South America), Schultesiophytum (1; S. chorianthum; northwestern South America), Ludovia (10; Central America, northwestern South America), Sphaeradenia (c 50; tropical America), Chorigyne (7; C. cylindrica, C. densiflora, C. ensiformis, C. paucinervis, C. pendula, C. pterophylla, C. tumescens; Costa Rica, Panamá), Stelestylis (4; S. anomala, S. coriacea, S. stylaris, S. surinamensis; northern tropical South America). – Central and tropical South America, the Greater Antilles. Sometimes climbing. Leaves sometimes distichous. Veins one or three. Inflorescence usually terminal (sometimes axillary), with spatha. Tepals ten to c. 30, with abaxial gland. Flowers spirally arranged. Male flowers usually with abaxial gland. Filaments swollen at base. Female flowers with four (to eight) tepals. Carpels four. Epigyny or with tepals. Staminodia long, filamentous, antepetalous. Placentation sometimes apical. Fruit berry-like, often compound, dehiscing with caducous lid, irregularly or by other unusual types of dehiscence.

|

Cladogram of Cyclanthaceae based on morphology (Eriksson 1994). |

PANDANACEAE R. Br. |

( Back to Pandanales ) |

Freycinetiaceae Brongn. ex Le Maout et Decne., Traité Général Bot.: 624. Jan-Apr 1868 [’Freycinetieae’]

Genera/species 5/c 720

Distribution Tropical West and Central Africa, Madagascar, the Seychelles, South India, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia to northern Australia, Melanesia, with the largest diversity in Malesia, Melanesia and Madagascar; some species in temperate parts of China, Japan or New Zealand; Martellidendron: Madagascar, the Seychelles; Sararanga: the Philippines, New Guinea, the Solomon Islands.

Fossils Pandaniidites consists of fossil pollen grains from the Late Maastrichtian and the Paleocene of North and South America. Their pandanaceous origin is highly doubtful, however (Araceae?).

Habit Usually monoecious, dioecious or polygamodioecious, trees, shrubs (Martellidendron, Pandanus, Sararanga) or lianas (Freycinetia; some species of Pandanus may be epiphytic). Some species are helophytes. Usually with axillary and often branched adventitious roots in the form of stout stilt roots or climbing roots, spines or other outgrowths. Stem growth distinctly sympodial (seemingly dichotomous).

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen? Stem vascular bundles collateral or bipolar; bipolar or tripolar bundles separate (not fusing at base). Primary and sometimes a certain amount of secondary lateral growth (secondary lateral growth usually absent). Vessels present in roots, stem and leaves. Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays? Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids usually P2cf type, with cuneate protein crystals and peripheral annular protein filaments (sometimes P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals). Nodes? Silica bodies absent. Oil cells present especially in Sararanga. Crystalliferous cells with one prismatic calciumoxalate crystal. Raphide cells frequent.

Trichomes Hairs usually absent (in Sararanga philippinensis stellate hairs on inflorescence receptacle).

Leaves Alternate (in Pandanus, Martellidendron and Freycinetia spirotristichous; in Sararanga ab initio spirotristichous, later spirotetrastichous), simple, entire, linear, differentiated into pseudopetiole and pseudolamina, with conduplicate to flat ptyxis, when mature M-shaped in cross-section. Stipules absent; leaf sheath well developed, usually open (sometimes closed). Leaf base in Freycinetia auriculate. Venation parallelodromous, with primary veins connected? by transversal veins; mid-vein of adaxial side often prickly. Stomata tetracytic. Mesophyll with mucilaginous cells and mucilaginous canals containing calciumoxalate as raphides or single prismatic crystals. Cuticular wax crystalloids as non-orientated aggregated platelets or longitudinally aggregated rodlets (Strelitzia type) or amorphous. Leaf margin usually serrate-dentate.

Inflorescence Usually terminal (sometimes lateral or axillary), cymose: in Pandanus raceme-like, simple or compound, in Freycinetia spike-like in compound raceme- or umbel-like cymose inflorescences, sometimes separate spikes, and in Sararanga panicles. Inflorescence surrounded by a usually petaloid bract (a spatha rich in fragrant ethereal oils). Flowers often difficult to separate from partial inflorescences (especially male flowers in Freycinetia).

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Hypogyny (at least in some species of Freycinetia). Tepals usually strongly reduced or absent (tepals in Sararanga reduced, sepaloid, connate into a cupule). Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens (two or) nine to more than 300 (delimitation of single flowers often indistinct). Filaments simple or branched, smooth or papillate, free or connate below (in Pandanus usually free and inserted on a peltate stemonophore), free from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile?, tetrasporangiate, possibly latrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective often somewhat prolonged. Tapetum secretory or amoeboid-periplasmodial? Female flowers in Freycinetia, Martellidendron and some species of Pandanus with staminodia.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains monoporate to monosulcate or monoulcerate (rarely inaperturate?), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate and one-layered (Pandanus) or semitectate and three-layered (Freycinetia, Martellidendron, Sararanga and some species of Pandanus), with columellate infratectum, in Sararanga and Martellidendron reticulate, in Pandanus usually spinulate (sometimes smooth), in Freycinetia smooth.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of a single carpel (pseudomonomerous?) or numerous (in Sararanga up to c. 70 to 80?) usually more or less connate carpels; carpels often incompletely closed. Ovary superior (or sometimes inferior?), unilocular (apocarpous or monomerous?) to multilocular (syncarpous), with (intra-ovarian) hairs inside. Style single, simple, short or absent. Stigma reniform or hippocrepomorphic (in some species of Pandanus elongate), ventral or dorsal in unicarpellate pistils, centrifugal or centripetal in multicarpellate pistils, type? Male flowers in Freycinetia, Sararanga, Martellidendron and some species of Pandanus with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation parietal (when ovary unilocular) or axile to subbasal (when ovary multilocular). Ovules usually one to five (in Freycinetia numerous) per carpel, anatropous, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle usually endostomal (in Freycinetia bistomal). Outer integument ? cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Obturator present. Hypostase often present. Parietal cell formed from archesporial cell. Parietal tissue one to five cell layers thick. Nucellar cap present. Megagametophyte in Freycinetia monosporous, Polygonum type, in Pandanus usually disporous, Allium type. Antipodal cells in Freycinetia three, in Pandanus often 64 to more than 200, due to immigration of nuclei from megasporangium; often proliferating, persistent. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear (in Pandanus often aberrant). Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A berry (in Freycinetia usually with fibres or crystals in pericarp, in Sararanga without fibres or crystals) or a drupe with fibre strands in pericarp (Martellidendron, Pandanus), in some species entirely or partially fusing with one another and with inflorescence receptacle into syncarps. Pericarp in Pandanus sometimes rich in oils.

Seeds Aril absent. Strophiole sometimes developed from raphe. Testa in Pandanus thin, in Freycinetia and Sararanga approx. five cell layers thick, with developed exotesta. Endotesta in some species of Freycinetia well developed, with two persistent cuticle layers. Tegmen? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, proteinaceous and usually oily (in Freycinetia starchy). Embryo small, straight, often rudimentary, chlorophyll? Cotyledon one, not photosynthesizing. Cotyledon hyperphyll compact, not assimilating. Hypocotyl internode long (Freycinetia). Coleoptile absent. Radicula branched (Pandanus). Germination?

Cytology n = 25, 28, 30 (Freycinetia); n = 30 etc. (Pandanus) – Aneuploidy occurring in Pandanus.

DNA

Phytochemistry Caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid and piperidine alkaloids present. Flavonols and other flavonoids, ellagic acid, tannins, proanthocyanidins, saponins, cyanogenic compounds, and quinones not found.

Use Ornamental plants, thatching, textiles, carpets, ropes, basketry and other handicraft, vegetables, fruits (Freycinetia, Pandanus), perfumes and flavours (pollen and bracts from Pandanus).

Systematics Sararanga (2; S. philippinensis: the Philippines; S. sinuosa: New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, Solomon Islands), Freycinetia (c 200; Sri Lanka to New Zealand and the Hawaiian Islands), Martellidendron (6–7; M. androcephalanthos, M. cruciatum, M. gallinarum, M. hornei, M. karaka, M. kariangense; Madagascar, the Seychelles), Benstonea (c 60; India, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea, Queensland, Solomon Islands, Fiji), Pandanus (c 450; tropical regions in the Old World).

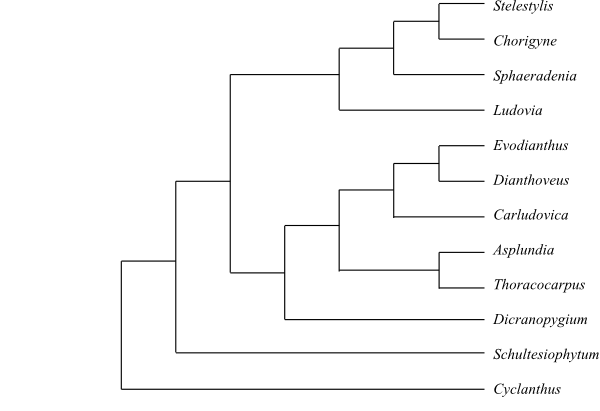

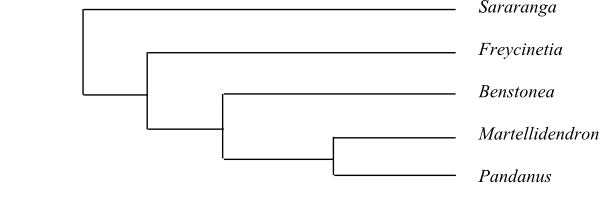

Pandanaceae are sister-group to Cyclanthaceae. Sararanga is sister to the remaining Pandanaceae. Martellidendron is recovered as sister to Pandanus by Buerki & al. (2012), whereas Benstonea was sister to Pandanus in a later analysis (Buerki & al. 2016).

|

Bayesian half-compatible consensus tree of Pandanaceae based on DNA sequence data (Buerki & al. 2012). |

|

Bayesian half-compatible consensus tree of Pandanaceae based on DNA sequence data (Buerki & al. 2016). |

STEMONACEAE Caruel |

( Back to Pandanales ) |

Roxburghiaceae Wall., Plant. Asiat. Rar. 3: 50. 15 Aug 1832; Roxburghiales Wall. in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp. Regn. Veg.: 8. Sep-Oct 1835 [‘Roxburghiaceae’]; Croomiaceae Nakai, Iconogr. Pl. As. Orient. 2: 159. Nov 1937; Pentastemonaceae Duyfjes in Blumea 36: 552. 9 Jun 1992; Stemonales Takht. ex Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.: lx. 23 Dec 2001

Genera/species 4/30–32

Distribution Sri Lanka, southeastern China, Taiwan, southern Japan, Southeast Asia, Malesia to northern Australia, southeastern United States.

Fossils Spirellea, from the German Maastrichtian and Paleocene, has provisionally been assigned to Stemonaceae.

Habit Usually bisexual (in Stichoneuron and often in Pentastemona functionally unisexual), perennial herbs, twining to climbing (Stemona) or erect, often with root nodules.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen absent. Stem in Stemona and Stichoneuron with two interlacing peripheral cylinders of vascular bundles, collateral in outer cylinder, amphivasal in inner cylinder; stem in Croomia with a single cylinder of amphivasal bundles. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels present in root and stem (rarely in leaves). Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals. Nodes? Tanniniferous cells numerous. Calciumoxalate raphides abundant. Calciumoxalate crystals in Stemona and Stichoneuron long prismatic, in Pentastemona as styloids, raphides, druses, and single crystals.

Trichomes Hairs usually unicellular or absent (in Pentastemona multicellular, usually uniseriate).

Leaves Usually alternate (distichous) or opposite (rarely verticillate), simple, entire, differentiated into pseudopetiole and pseudolamina, with ? ptyxis. Scaly leaves usually present on rhizome (absent in Pentastemona). Stipules absent; leaf sheath present or absent. Venation parallelodromous; primary veins connected by thin transversal veins. Stomata usually anomocytic (in Pentastemona tetracytic, paracytic or cyclocytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids absent. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Usually axillary, few-flowered cymose of various shape (sometimes umbel-like; in Stemona phyllantha epiphyllous; in Pentastemona simple or compound raceme-like), or flowers solitary axillary.

Flowers Actinomorphic (rarely somewhat zygomorphic). Pedicel articulated. Hypogyny or sometimes almost half epigyny (in Pentastemona epigyny, with hypanthium). Tepals usually 2+2 (in Pentastemona five in one whorl), usually with valvate (in Pentastemona quincuncial) aestivation, usually caducous (in Pentastemona persistent), sepaloid or petaloid, free or connate at base (in Pentastemona connate for most of their length into a tube). Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens usually 2+2, obdiplostemonous? (in Pentastemona five in one whorl, with corona-like appendages). Filaments free (Croomia, Stichoneuron) or connate at base (Stemona), usually free from tepals (in Stichoneuron adnate to tepal bases; in Pentastemona connate into a carnose annular structure and adnate to base of tepals and perianth tube). Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate (thecae sometimes connate at apex, in Stemona with an adaxial appendage as a central ridge), usually introrse (in Pentastemona latrorse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); each connective in Stemona with a long apical appendage; connective in Pentastemona together with hypanthium apex and ovary fused into a swollen discoid structure with five (nectariferous?) pockets and in each of these pockets a theca from each of two adjacent anthers; inner appendage of filament tube in Pentastemona adnate to stigmatic lobes. Tapetum secretory. Female flowers with staminodia.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains monosulcate (Croomia, Stemona) or inaperturate (Pentastemona, Stichoneuron), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine usually tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, microreticulate (Stemona, Stichoneuron) or reticulate (Croomia; in Pentastemona intectate, scabrate).

Gynoecium Pistil composed of one (Croomia, Stemona, Stichoneuron) or (two or) three (Pentastemona) connate carpels. Ovary usually more or less superior (rarely inferior), unilocular. Style usually absent (in Pentastemona single, simple, short). Stigma capitate (in Pentastemona wide and flattened, usually trilobate or quadrilobate), papillate, type? Male flowers with pistillodium.

Ovules Placentation basal (Stemona), apical (Croomia, Stichoneuron) or intrusively parietal (Pentastemona). Ovules two to c. 50 per carpel, anatropous or hemianatropous (or orthotropous?), apotropous, ascending or horizontal, bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal. Outer integument three to five cell layers thick. Inner integument two or three cell layers thick. Funicular obturator present in Stemona. Hypostase present at least in Pentastemona. Parietal cell formed from archesporial cell. Parietal tissue one or two cell layers thick. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Synergids with a filiform apparatus. Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis asterad.

Fruit Usually a capsule with two valves (sometimes indehiscent; in Pentastemona a many-seeded berry with persistent tepals).

Seeds Seed in Pentastemona to one third covered with an annular arillode. Elaiosome formed (in Croomia and Stemona) by uniseriate or bladder-like hairs from hilum, raphe or micropyle. Seed coat testal. Testa usually multi-layered (in Pentastemona two-layered), ridged, multiplicative, tanniniferous. Sarcotesta usually absent (exotesta in Pentastemona a thin translucent sarcotesta). Endotestal cell walls thickened (in Pentastemona with massive U-shaped thickenings). Tegmen two-layered, sometimes persistent, with thickened cell walls. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, with oils, starch and aleurone. Embryo small, usually little differentiated (in Pentastemona well differentiated), chlorophyll? Cotyledon one, not photosynthesizing. Hypocotyl internode absent. Cotyledon hyperphyll compact, not assimilating. Coleoptile absent. Radicula well differentiated, persistent. Germination?

Cytology n = 7 (Stemona, Pentastemona); n = 9 (Stichoneuron); n = 12 (Croomia)

DNA

Phytochemistry Unsufficiently known. Tannins, lactone alkaloids (tuberostemonine in Croomia and Stemona), and saponins (in Stemona) present. Cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Unknown.

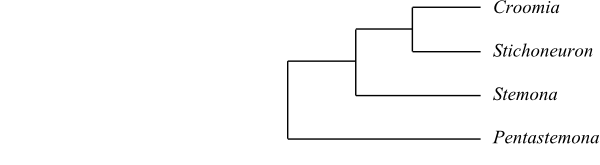

Systematics Pentastemona (2; P. egregia, P. sumatrana; Sumatra), Stemona (20–22; Sri Lanka, the Nicobar Islands, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Malesia to tropical Australia), Stichoneuron (5; S. bognerianum, S. calcicola, S. caudatum, S. halabalense, S. membranaceum; Assam to the Malay Peninsula), Croomia (3; C. heterosepala, C. japonica: southeastern China, southern Japan; C. pauciflora: southeastern United States).

Pentastemona is sister to the remaining Stemonaceae.

Rudall & Bateman (2006) found Triuridaceae as nested within Stemonaceae, Pentastemona being sister to Triuridaceae and the remaining Stemonaceae.

The pyrrolo- or pyrido(-1,2-α-)azepine alkaloids present in Stemonaceae, are probably an apomorphy in Stemonaceae.

|

Cladogram of Stemonaceae based on morphology and DNA sequence data (Caddick & al. 2002; Rudall & al. 2005). |

TRIURIDACEAE Gardner |

( Back to Pandanales ) |

Triuridales J. D. Hooker in Le Maout et Decaisne, General Syst. Bot.: 1018. 25 Apr 1873 [’Triurales’]; Lacandoniaceae E. Martínez et Ramos in Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 76: 128. 25 Apr 1989; Triuridanae Thorne ex Reveal in Novon 2: 236. 13 Oct 1992; Triurididae Takht. ex Reveal in Novon 2: 235. 13 Oct 1992

Genera/species 7/c 50

Ditribution Tropical Central and East Africa, northern Madagascar, the Seychelles, East and Southeast Asia, Malesia to Queensland, islands in southwestern Pacific, Central America to central South America.

Fossils Mabelia and Nuhliantha are fossil male flowers which were described from the Late Cretaceous (Turonian) of New Jersey. Their systematic affiliation is highly doubtful and the morphology only partially corresponds to extant Triuridaceae. The flowers have six tepals and three stamens. The anthers are dithecal, extrorse, longicidally dehiscent, and possess an endothecium with U-shaped thickenings. The pollen grains are monosulcate.

Habit Usually monoecious, polygamomonoecious? or dioecious (in species of Sciaphila bisexual), usually perennial (rarely annual) herbs. Achlorophyllous mycoheterotrophic holoparasites.

Vegetative anatomy Arbuscular mycorrhiza present. Roots filiform, without medulla, with Paris type mycorrhiza in cortical parenchyma with a thickness of one to three cell layers. Root stele monarch or diarch, solid. Root endodermis with cell wall thickenings. Stem vascular cylinder consisting of narrow bundles. Phellogen absent. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels absent. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals. Nodes? Silica bodies absent. Calciumoxalate raphides rare. Single calciumoxalate crystals absent.

Trichomes Hairs absent.

Leaves: Alternate (spiral), simple, entire, scaly, with ? ptyxis. Stipules absent; leaf sheath sometimes well developed, closed. Venation consisting of a single vascular strand. Stomata absent. Cuticular wax crystalloids as parallel series of platelets, transversely arranged in each series and resembling ‘electromagnetic field lines’ (Convallaria type). Mesophyll without calciumoxalate crystals. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Terminal, usually raceme (inflorescence rarely cymose, or flowers solitary). Floral prophyll (bracteole) usually absent.

Flowers Actinomorphic (male flowers in Kupea and Kihansia zygomorphic), usually small. Hypogyny. Tepals usually three (antesepalous or antepetalous) or 3+3 (rarely four, 4+4 or 5+5), with valvate aestivation, petaloid, acute, often with filiform apical appendage (sometimes with glandular apex), persistent, more or less connate; median tepal in outer whorl adaxial. Nectary absent? Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens usually three or 3+3 (rarely two or 4+4), sometimes on central androphore consisting of receptacular or connective tissue. Filaments thick, free or connate, free from tepals, or absent. Anthers basifixed or dorsifixed, non-versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (sometimes disporangiate or trisporangiate), usually extrorse (sometimes introrse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits; sometimes transversal or diagonal); connective appendage usually absent (appendage long in Seychellaria madagascariensis and Andruris). Tapetum secretory, with uni-, bi- or trinucleate cells; or amoeboid-periplasmodial, with ab initio uninucleate cells (sometimes intermediate). Staminodia usually absent (in male flowers of Seychellaria three staminodia alternating with three fertile stamens).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains usually inaperturate (in Sciaphila, Seychellaria and Triuris also monosulcate), shed as monads, tricellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or intectate, with columellate? infratectum, verruculate to verrucate, granulate, gemmate (with spinulate or tuberculate gemmae), or absent.

Gynoecium Carpels six to c. 50, plicate, secondarily free; fruiting carpels often with irregular surface. Ovary superior, unilocular (apocarpy), sometimes on gynophore. Stylodia narrow, solid, (sub)basal to (sub)apical, usually lateral. Stigmas often penicillate, papillate or non-papillate, Dry type? Pistillodium usually absent.

Ovules Placentation basal. Ovules usually one (in Kupea? two) per carpel, anatropous, ascending, bitegmic, tenuinucellar. Micropyle endostomal. Outer integument two cell layers thick. Inner integument two cell layers thick. Hypostase present. Parietal cell not formed (parietal tissue absent). Nucellar cap not formed. Megagametophyte usually monosporous, Polygonum type (in Triuris probably tetrasporous, Fritillaria type). Endosperm development ab initio nuclear. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit An assemblage of abaxially dehiscent follicles or (in Soridium) achenes.

Seeds Aril absent. Seed coat testal or endotestal. Exotesta often persistent. Endotesta often with inner cuticle strongly thickened. Tegmen absent. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, oily, fatty and proteinaceous and with hemicellulose (in young plants often starchy). Embryo small, undifferentiated, chlorophyll? Cotyledon one. Germination?

Cytology n = (9) 11, 12(–16), 24 – Agamospermy (parthenogenesis) may be frequent.

DNA

Phytochemistry Unknown.

Use Unknown.

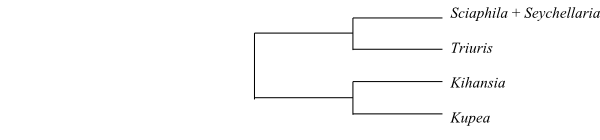

Systematics Kupeeae Cheek in Kew Bull. 58: 940. Feb 2004. Kupea (1; K. martinetugei; Bakossi Mountains in western Cameroon); Kihansia (1; K. lovettii; Udzungwa Mountains in Tanzania). – Triurideae Miers in J. Lindley, Veg. Kingd., ed. 3: 144a, 144b. Aug 1853. Triuris (4; T. alata, T. brevistylis, T. hexophthalma, T. hyalina; the Yucatan Peninsula, Guatemala, northern tropical South America, Brazil). – Sciaphileae Hook. f. in J. E. M. Le Maouit et J. Decaisne, General Syst. Bot.: 797. 25 Apr 1873. Sciaphila (36; tropical and subtropical regions on both hemispheres). – Unplaced Triuridaceae Soridium (1; S. spruceanum; Belize, Guatemala, northern tropical South America); Peltophyllum (2; P. caudatum, P. luteum; Brazil, Paraguay, northern Argentina), Triuridopsis (2; T. intermedia, T. peruviana; Peru, Bolivia).

Kupea is sister to the remaining Triuridaceae (Rudall & Bateman 2006; Mennes & al. 2013). Rudall & Bateman (2006) identified Triuridaceae as nested inside Stemonaceae. A phylogeny comprising most genera of Triuridaceae is published by Mennes & al. (2013) and they found the following topology: [[Sciaphila+Triuris][Kihansia+Kupea]].

Apocarpy with numerous carpels is a reversal. Multiplication (delayed determinacy) of the carpel number in an ancestor with free carpels in unisexual flowers, or, alternatively, flowers evolving from an ancestor with three connate carpels in unisexual flowers are two potential evolutionary scenarios which might explain the apocarpous multicarpellary female flowers in Triuridaceae, according to Rudall & Bateman (2006). The third alternative, that the flower in Triuridaceae actually represents a pseudanthium, is less probable.

Lacandonia, with two species described, represents a mutation in Triuris causing shift of organ positions (heterotopy). The androecium is central and the gynoecium peripheral, i.e. the carpels are extrastaminal. The carpellary and staminal precursors in Lacandonia develop from a common primordium. In Triuris, the precursors are formed from compound primordia.

|

Phylogeny of Triuridaceae based on DNA sequence data (Mennes & al. 2013). |

VELLOZIACEAE J. Agardh |

( Back to Pandanales ) |

Barbaceniaceae Arn., Encycl. Brit., ed. 7, 5: 134. 9 Mar 1832 [‘Barbacenieae’]; Acanthochlamydaceae (S.-C. Chen) P.-C. Kao in Acta Bot. Sichuan 2: 1. Mar 1989; Velloziales R. Dahlgren ex Reveal in Novon 2: 239. 13 Oct 1992

Genera/species 5/265–270

Distribution Tropical and southern Africa, Madagascar, southwestern Arabian Peninsula, southeastern Tibet, southwestern China, Panamá and northwestern South America, Peru to Argentina.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Usually bisexual (in Barbaceniopsis unisexual), usually perennial herbs (sometimes shrubby or almost tree-like). Xeromorphic. Stem more or less woody, covered with persistent leaves and leaf sheaths usually intermingled with extensive adventitious roots.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen? Primary vascular tissue in scattered bundles. Cortex present in three different zones. Secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels present in root and leaves (sometimes also in stem). Vessel elements in root with simple perforation plates, in stem and leaves with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids. Wood rays? Axial parenchyma? Phloem present in at least smaller bundles in two abaxial-lateral vascular strands. Sieve tube plastids P2cc type (with only starch and many cuneate protein crystals), P2cca type (with starch, many cuneate protein crystals and a single large loosely-packed polygonal protein crystal), P2ccl type (with starch, many cuneate and additional loosely-packed square, rhomboidal etc. protein crystals), P2cclf type (with starch, many cuneate and additional loosely-packed square, rhomboidal etc. protein crystals, and protein filaments), or P2ccaf type (with starch, many cuneate protein crystals and a single large loosely-packed polygonal protein crystal, and protein filaments). Nodes? Vascular tissues with resin. Tanniniferous cells present in many species of Vellozioideae. Calciumoxalate raphides and styloids sometimes present. Rhomboidal crystals sometimes present in leaves.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate or branched, often tufted; flowers often with multicellular glandular hairs of different shape.

Leaves Alternate (tristichous), simple, entire, linear, with conduplicate to flat ptyxis. Stipules absent; leaf sheath well developed. Leaf base persistent. Venation parallelodromous. Stomata usually twice (brachy)paracytic, present in longitudinal furrows. Cuticular wax crystalloids usually absent (rarely as longitudinally aggregated rodlets, Strelitzia type). Mesophyll often with mucilaginous cells containing calciumoxalate raphides. Leaf margin serrate-dentate to spinulose or entire.

Inflorescence Terminal – gradually lateral due to stem growth – and cymose, one- to many-flowered (in Acanthochlamys capitate), or flowers solitary.

Flowers Actinomorphic, often large. Hypanthium at least as long as ovary and adnate to this. Usually epigyny (rarely half epigyny). Tepals 3+3, petaloid, usually free (in Acanthochlamys connate at base); inner tepals large (sometimes with corona consisting of free or connate tepal appendages alternatively filament appendages); median outer tepal sometimes adaxial. Septal nectaries present in ovary wall. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens usually 3+3 (in Vellozia often 18 to 66, due to division of staminal initials and ramification of filament appendages, in three or six fascicles with connate anthers). Filaments subulate, simple and often with adaxial appendages at base (Vellozia), sometimes flat and bifid, free from each other and from tepals or adnate to corona (Barbacenia) or to tepals (Barbaceniopsis, some species of Vellozia). Anthers basifixed to dorsifixed, non-versatile?, usually tetrasporangiate (in Acanthochlamys disporangiate; in ‘Xerophyta’ schnizleiniana decasporangiate), usually introrse to latrorse (rarely extrorse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis successive. Pollen grains usually monosulcate (in Vellozia occasionally inaperturate), usually shed as monads (rarely as dyads or tetrads), bicellular or tricellular at dispersal. Exine semitectate, with columellate infratectum, reticulate or rugate, often verrucate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of three connate carpels. Ovary usually inferior (rarely semi-inferior), trilocular. Style single, simple, long, narrow, widened at apex. Stigma capitate, clavate or trilobate, with apical or subapical lobes, delimited to entirely confluent, linear to orbicular, type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation intrusively parietal to axile (laminar). Ovules c. 30 to more than 50 per carpel, anatropous, horizontal, bitegmic, tenuinucellar to weakly crassinucellar. Micropyle usually bistomal (sometimes endostomal). Outer integument ? cell layers thick. Inner integument ? cell layers thick. Funicular obturator often present. Parietal cell not formed (parietal tissue absent). Megasporangial epidermis usually (always?) without periclinal cell divisions. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development usually helobial (in Acanthochlamys nuclear). Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A capsule, poricidal, loculicidal or with intercostal openings.

Seeds Aril usually absent. Seed coat usually exotestal. Testa mainly consisting of thick outer exotestal epidermis; epidermal cells with phlobaphene; testa in Acanthochlamys collapsed. Endotesta and tegmen usually more or less crushed. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, outer layers with oils and aleurone, inner layers with starch grains. Embryo usually small (in Acanthochlamys large), chlorophyll? Cotyledon one. Hypocotyl internode short. Cotyledon hyperphyll compact, not assimilating. Coleoptile absent. Collar rhizoids? Germination?

Cytology x = 8; n = 19 (Acanthochlamys); n = 7, 8, 17, 24 (Vellozioideae) – Polyploidy occurring.

DNA The 6 bp deletion in atpA is absent at least in Talbotia (in Barbaceniopsis?).

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), O-methylated, C-methylated and prenylated lipophilic flavonoids, flavone-C-glycosides, and resins consisting of oxidized tetracyclic and pentacyclic diterpenes and triterpenes present. Steroidal saponins present in Acanthochlamys? (triterpene saponins in ’Barbacenia’?). Ellagic acid, proanthocyanidins, and cyanogenic compounds not found. Alkaloids absent (not found) at least in Acanthochlamys.

Use Ornamental plants, paint brushes, etc.

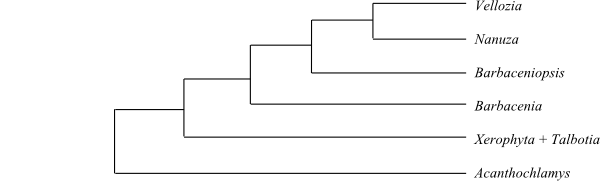

Systematics Acanthochlamys is sister to the remaining Velloziaceae. Mello-Silva & al. (2011), in a study comprising 48 species in all ten formerly recognized genera and using both molecular and morphological data, identified the topology [Acanthochlamys+[Xerophyta+[Barbacenia+ [Barbaceniopsis+[Nanuza+Vellozia]]]]].

Acanthochlamydoideae P. C. Kao in Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 19: 323. Aug 1981

1/1. Acanthochlamys (1; A. bracteata; southeastern Tibet, western Sichuan). – Perennial herb. Root vascular cylinder actinostele, usually tetrarch (rarely triarch), without medulla. Vessels also in stem and leaves. Vessel elements with simple perforation plates. Peduncular anatomy unusual; stipe on one side with a longitudinal furrow, cordate in cross-section; stele consisting of a central tetrarch vascular cylinder resembling that in roots; in upper part of peduncle vascular cylinder dissolving into five or six collateral bundles; outside stele inner part of cortex sclerified and inside longitudinal furrow cortex transversed by two obliquely arranged bundles (a single trace supplying an involucral bract), resembling those forming leaf mid-vein, although being fused in their xylem parts; peduncular anatomy resembling that in a rhizome-enclosing leaf sheath. Raphides and tanniniferous cells absent. Mid-vein with two vascular bundles arranged ‘back-to-back’. Leaves with comparatively large basal adaxial ligule sheathing stem. Inflorescence compound capitate, with long peduncle. Tepals connate at base. Septal nectaries absent. Antepetalous anthers positioned higher than antesepalous anthers in perianth tube. Endosperm development nuclear. Testal cells elongate, lignified. Tegmen tanniniferous. Embryo large. n = 19. – Mello-Silva & al. (2011) listed stem cortex divided into three regions, two phloem strands, persistent leaves, and violet tepals as morphological synapomorphies of Acanthochlamys.

Vellozioideae Rendle, Class. Fl. Plants, ed. 2, 1: 309. 1930

4/265–270. Xerophyta (c 30; tropical Africa, Madagascar, southwestern Arabian Peninsula), Barbacenia (c 110; northern South America), Barbaceniopsis (4; B. boliviensis, B. castillonii, B. humahuaquensis, B. vargasiana; the Andes in Peru, Bolivia and northwestern Argentina), Vellozia (c 125; tropical America from Panamá to Argentina, with their largest diversity in southeastern Brazil). – Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, Madagascar, South America. Woody or herbaceous. Adventitious roots alternating with leaves and during growth often penetrating the lower, older, persistent fibrous leaf sheaths gradually covering these at base.Velamen sometimes present. Vessels often only in roots. Vessel elements with simple or scalariform perforation plates. Petiole vascular bundles with transfusion tracheids. Phloem present in two abaxial-lateral vascular strands. Stomata (brachy)paracytic. Leaf margin usually spiny. Inflorescence sessile or almost sessile, often one-flowered. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) lateral. Hypanthium sometimes present. Tepals with valvate aestivation, largely free. Corona present in Barbacenia, usually adnate to (part of?) androecium. Septal nectaries present. Filaments usually adnate to (in some species of Xerophyta free from) hypanthial mouth. Anthers long, sometimes dithecal, sometimes in three or six fascicles (anthers sometimes connate within fascicles), sometimes numerous. Pollen grains sometimes shed in tetrads. Multicellular glandular hairs sometimes present on abaxial side of ovary. Stigmas large, erect or spreading. Placentae bilobate. Micropyle usually bistomal (sometimes endostomal). Endothelium and funicular obturator often present. Endosperm development helobial; cell wall formation in small chalazal space preceding that in large micropylar space. Testa tanniniferous. Exotesta often thickened. Tegmen in Pleurostima clade of Barbacenia tanniniferous. Embryo often short. Collar rhizoids present. n = 7 (Barbacenia), 8, 17, 24. Biflavonoids present in some species of Vellozia. – The multicellular glandular hairs sometimes present on the ovary closely resemble the glands in some Dioscorea (Dioscoreaceae; Caddick & al. 2000). Mello-Silva & al. (2011) stated that leaves with marginal vascular bundles, presence of transfusion tracheids and inflorescence without axis are synapomorphies of Vellozioideae. Xerophyta has basally loculicidal capsules. The American clade [Barbacenia+[Barbaceniopsis+Vellozia]] is supported by homoplastic morphological characters only, whereas Barbacenia itself has a double sheath in foliar vascular bundles and a corona. Finally, they did not manage to find any unambiguous morphological synapomorphies for the clade [Barbaceniopsis+Vellozia], although Barbaceniopsis alone is supported by five characters and Vellozia by inner stem cortex cells with secondary walls and stigma with horizontal lobes. Vellozia is characterized by, e.g., pollen grains shed in tetrads.

|

Cladogram of Velloziaceae based on DNA sequence data (Mello-Silva & al. 2011). |

Literature

Alcantara S, Ree RH, Mello-Silva R. 2018. Accelerated diversification and functional trait evolution in Velloziaceae reveal new insights into the origins of the campos rupestres’ exceptional floristic richness. – Ann. Bot. 122: 165-180.

Álvarez-Buylla ER, Ambrose BA, Flores-Sandoval E, Englund M, Garay-Arroyo A, García-Ponce B, de la Torre-Bárcena E, Espinosa-Matías S, Martínez E, Piñeyro-Nelson A, Engström P, Meyerowitz EM. 2010. B-function expression in the flower center underlies the homeotic phenotype of Lacandonia schismatica (Triuridaceae). – Plant Cell 22: 3543-3559.

Alves RJV. 1994. Morphological age determination and longevity in some Vellozia populations in Brazil. – Folia Geobot. Phytotaxon. 29: 55-59.

Ambrose BA, Espinosa-Matís S, Vázquez-Santana S, Márquez-Guzmán J, Alvarez-Buylla ER. 2006. Comparative developmental series of the Mexican triurids support a euanthial interpretation for the unusual reproductive axes of Lacandonia schismatica (Triuridaceae). – Amer. J. Bot. 93: 15-35.

Ayensu ES. 1968a. Comparative vegetative anatomy of the Stemonaceae (Roxburghiaceae). – Bot. Gaz. 129: 160-165.

Ayensu ES. 1968b. The anatomy of Barbaceniopsis, a new genus recently described in the Velloziaceae. – Amer. J. Bot. 55: 399-405.

Ayensu ES. 1969a. The identity of Vellozia uaipenensis – anatomical evidence. – Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 18: 291-298.

Ayensu ES. 1969b. Leaf-anatomy and systematics of Old World Velloziaceae. – Kew Bull. 23: 315-335.

Ayensu ES. 1973a. Biological and morphological aspects of Velloziaceae. – Biotropica 5: 135-149.

Ayensu ES. 1973b. Phytogeography and evolution of the Velloziaceae. – In: Meggers BJ, Ayensu ES, Duckworth WD (eds), Tropical forest ecosystems in Africa and South America. A comparative review, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., pp. 105-119.

Ayensu ES. 1974. Leaf anatomy and systematics of New World Velloziaceae. – Smithsonian Contr. Bot. 15: 1-125.

Ayensu ES, Skvarla JJ. 1974. Fine structure of Velloziaceae pollen. – Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 101: 250-266.

Bande MB, Awasthi N. 1986. New thoughts on the structure and affinities of Viracarpon hexaspermum Sahni from the Deccan Intertrappean beds of India. – Stud. Bot. Hung. 19: 13-22.

Beach JH. 1982. Beetle pollination of Cyclanthus bipartitus (Cyclanthaceae). – Amer. J. Bot. 69: 1074-1081.

Beccari O. 1890. Le Triuridaceae della Malesia. – Malesia 3: 318-344.

Behnke H-D, Treutlein J, Wink M, Kramer K, Schneider C, Kao PC. 2000. Systematics and evolution of Velloziaceae, with special reference to sieve-element plastids and rbcL sequence data. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 134: 93-129.

Behnke H-D, Kramer K, Hummel E. 2002. Xerophyta seinei (Velloziaceae), a distinctive new species from Zimbabwe. – Taxon 51: 55-67.

Behnke H-D, Hummel E, Hillmer S, Sauer-Gürth H, Gonzalez J, Wink M. 2013. A revision of African Velloziaceae based on leaf anatomy characters and rbcL nucleotide sequences. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 172: 22-94.

Bennett BC, Alarcón R, Cerón C. 1992. The ethnobotany of Carludovica palmata Ruiz & Pavón (Cyclanthaceae) in Amazonian Ecuador. – Econ. Bot. 46: 233-240.

Biradar NV, Bonde SD. 1990. The genus Cyclanthodendron and its affinities. – Proceedings, 3rd IOP Conference, Melbourne, pp. 51-57.

Bonde SD. 1990. A new palm peduncle Palmostroboxylon umariense (Arecaceae) and a fruit Pandanusocarpon umariense (Pandanaceae) from the Deccan Intertrappean Beds of India. – Proc. 3rd IOP Conference, Melbourne, pp. 59-65.

Bosser J, Guého J. 2002. Deux nouvelles espèces de Pandanus (Pandanaceae) de l’Île Maurice. – Adansonia, sér. III, 24: 239-242.

Bouman F, Devente N. 1992. A comparison of the structure of ovules and seeds in Stemona (Stemonaceae) and Pentastemona (Pentastemonaceae). – Blumea 36: 501-514.

Buerki S, Callmander MW, Devey DS, Chappell L, Gallaher T, Munzinger J, Haevermans T, Forest F. 2012. Straightening out the screw-pines: a first step in understanding phylogenetic relationships within Pandanaceae. – Taxon 61: 1010-1020.

Buerki S, Gallaher T, Booth T, Brewer G, Forest F, Pereira JT, Callmander MW. 2016. Biogeography and evolution of the screw-pine genus Benstonea Callm. & Buerki (Pandanaceae). – Candollea 71: 217-229.

Callmander MW. 2000. Pandanus subg. Martellidendron (Pandanaceae) I: new findings on Pandanus hornei Balf. f. (sect. Seychellea) from the Seychelles. – Webbia 55: 317-329.

Callmander MW. 2001. Pandanus subg. Martellidendron (Pandanaceae) II: revision of sect. Martellidendron Pic. Serm. in Madagascar. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 137: 353-374.

Callmander MW, Buerki S. 2016. Two new species of Benstonea Callm. & Buerki (Pandanaceae) from Sabah (Borneo, Malaysia). – Candollea 71: 257-263.

Callmander MW, Laivao MO. 2002. Le genre Pandanus (Pandanaceae) à Madagascar: révision de la section Dauphinensia St John. – Bot. Helv. 112: 47-67.

Callmander MW, Laivao MO. 2003. New findings on Pandanus sect. Imerinenses and sect. Rykiella (Pandanaceae) from Madagascar. – Adansonia, sér. III, 25: 53-63.

Callmander MW, Wohlhauser S, Laivao MO. 2001. Une nouvelle section du genre Pandanus (Pandanaceae) à Madagascar: Pandanus sect. Tridentistigma. – Adansonia, sér. III, 23: 49-57.

Callmander MW, Wohlhauser S, Laivao MO. 2003. Les Pandanus sect. Acanthostyla Martelli (Pandanaceae) d’altitude du nord de Madagascar, avec description de deux nouvelles espèces. – Candollea 58: 63-74.

Callmander MW, Chassot P, Küpfer P, Lowry PP II. 2003. Recognition of Martellidendron, a new genus of Pandanaceae, and its biogeographic implications. – Taxon 52: 747-762.

Callmander MW, Wohlhauser S. Gautier L. 2003. Notes biogéographiques sur les Pandanaceae du nord de Madagascar. – Candollea 58: 351-367.

Callmander MW, Lowry II PP, Forest F, Devey DS, Beentje H, Buerki S. 2012. Benstonea Callm. & Buerki (Pandanaceae): characterization, circumscription, and distribution of a new genus of screw-pines, with a synopsis of accepted species. – Candollea 67: 323-345.

Callmander MW, Booth TJ, Beentje H, Buerki S. 2013. Update on the systematics of Benstonea (Pandanaceae): when a visionary taxonomist foresees phylogenetic relationships. – Phytotaxa 112: 57-60.

Callmander MW, Buerki S, Keim AP, Phillipson PB. 2014. Notes on Benstonea (Pandanaceae) from the islands of Halmahera, New Guinea and Sulawesi. – Phytotaxa 175: 161-165.

Campbell DH. 1909. The embryo-sac of Pandanus. – Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 36: 205-220.

Campbell DH. 1911. The embryo-sac of Pandanus. – Ann. bot. 25: 773-789.

Cheah CH, Stone BC. 1973. Chromosome studies of the genus Pandanus (Pandanaceae). – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 93: 498-529.

Cheek MR. 2003. Kupeeae, a new tribe of Triuridaceae from Africa. – Kew Bull. 58: 939-949.

Cheek MR, Williams SA, Etuge M. 2003. Kupea martinetugei, a new genus and species of Triuridaceae from Western Cameroon. – Kew Bull. 58: 225-228.

Chen S-C. 1981. Acanthochlamydoideae – a new subfamily of Amaryllidaceae. – Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 19: 323-329. [In Chinese with English summary]

Chuakul W. 2000. Stemona hutanguriana sp. nov. (Stemonaceae) from Thailand. – Kew Bull. 55: 977-980.

Coetzee H, Schijff HP van der, Steyn E. 1973. External morphology of the species of the South African Velloziaceae including a key based on external morphological characteristics. – Dinteria 9: 3-21.

Cox PA. 1981. Bisexuality in the Pandanaceae: new findings in the genus Freycinetia. – Biotropica 13: 195-198.

Cox PA. 1984. Chiropterophily and ornithophily in Freycinetia (Pandanaceae) in Samoa. – Plant Syst. Evol. 144: 277-290.

Cox PA. 1990. Pollination and the evolution of breeding systems in Pandanaceae. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 77: 816-840.

Cox PA, Huynh K-L, Stone BC. 1995. Evolution and systematics of Pandanaceae. – In: Rudall PJ, Cribb PJ, Cutler DF, Humphries CJ (eds), Monocotyledons: systematics and evolution, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, pp. 663-684.

Davidse G, Martínez S E. 1990. The chromosome number of Lacandonia schismatica (Lacandoniaceae). – Syst. Bot. 15: 635-637.

Drude O. 1889. Cyclanthaceae. – In: Engler A, Prantl K (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien II(3), W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 93-101.

Dutt BSM. 1970. Comparative embryology of angiosperms: Velloziaceae. – Bull. Indian Natl. Sci. Acad. 41: 373-374.

Duyfjes BEE. 1991. Stemonaceae and Pentastemonaceae; with miscellaneous notes on members of both families. – Blumea 36: 239-252.

Duyfjes BEE. 1992. Formal description of the family Pentastemonaceae with some additional notes on Pentastemonaceae and Stemonaceae. – Blumea 36: 551-552.

Duyfjes BEE. 1993. Pentastemonaceae. – In: Kalkman C et al. (eds), Flora Malesiana I, 11(2), Rijksherbarium/Hortus Botanicus, Leiden, pp. 393-398.

Duyfjes BEE. 1993. Stemonaceae. – In: Kalkman C et al. (eds), Flora Malesiana I, 11(2), Rijksherbarium/Hortus Botanicus, Leiden, pp. 399-409.

Engler A. 1888. Stemonaceae [Roxburghiaceae] . – In: Engler A, Prantl K (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien II(5), W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 8-9.

Engler A. 1889. Triuridaceae. – In: Engler A, Prantl K (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien II(1), W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 235-238.

Eriksson R. 1989. Chorigyne, a new genus of the Cyclanthaceae from Central America. – Nord. J. Bot. 9: 31-45.

Eriksson R. 1993. The rise and fall of Pseudoludovia andreana (Cyclanthaceae). – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 80: 458-460.

Eriksson R. 1994a. The remarkable weevil pollination of the neotropical Carludovicoideae (Cyclanthaceae). – Plant Syst. Evol. 189: 75-81.

Eriksson R. 1994b. Phylogeny of the Cyclanthaceae. – Plant Syst. Evol. 190: 31-47.

Eriksson R. 1995. The genus Sphaeradenia (Cyclanthaceae). – Opera Bot. 126: 1-106.

Ernst A, Bernard C. 1910. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Saprophyten Javas III. – Ann. Jard. Bot. Buitenzorg 23: 48-61.

Fagerlind F. 1940. Stempelbau und Embryosackentwicklung bei einigen Pandanazeen. – Ann. Jard. Bot. Buitenzorg 49: 55-83.

French CH, Klancy K, Tomlinson PB. 1983. Vascular patterns in stems of the Cyclanthaceae. – Amer. J. Bot. 70: 1386-1400.

Fukuhara T, Nagamasu H, Okada H. 2003. Floral vasculature, sporogenesis and gametophyte development in Pentastemona egregia (Stemonaceae). – Syst. Geogr. Plants 73: 83-90.

Furness CA, Rudall PJ. 2006. Comparative structure and development of pollen and tapetum in Pandanales. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 167: 331-348.

Furness CA, Rudall PJ, Eastman A. 2002. Contribution of pollen and tapetal characters to the systematics of Triuridaceae. – Plant Syst. Evol. 235: 209-218.

Gaff DF. 1971. Desiccation-tolerant flowering plants of southern Africa. – Science 174: 1033-1034.

Galeano-Garcés G, Bernal-Gonzalez R. 1984. Nuevas Cyclanthaceae de Colombia. – Caldasia 14: 27-35.

Gallaher T, Callmander MW, Buerki S, Keeley

SC. 2015. A long distance dispersal hypothesis for the Pandanaceae and the origins of the

Pandanus tectorius complex. – Molec. Phylogen. Evol. 83: 20-32.

Gallaher T, Callmander MW, Buerki S, Keeley SC. 2015. A long distance dispersal hypothesis for the Pandanaceae and the origins of the Pandanus tectorius complex. – Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 83: 20-32.

Gandolfo MA, Nixon KC, Crepet WL. 2002. Triuridaceae fossil flowers from the Upper Cretaceous of New Jersey. – Amer. J. Bot. 89: 1940-1957.

Ganguly B. 1959. Chromosome number in Pandanales. – Curr. Sci. 28: 82.

Gao B-C. 1987. The sociological characteristics and pollen morphology of Acanthochlamys. – Acta Bot. Yunnan. 9: 401-405. [In Chinese with English summary]

Gao B-C, Li P. 1993. Studies on the morphology and embryology of Acanthochlamys bracteata: I. Morphological and anatomic studies on vegetative organs. – J. Sichuan Univ. (Science ed.) 30: 534-537. [In Chinese with English summary]

Garcin H. 1958. Contribution à la connaissance de la structure florale des Cyclanthacées. – Nat. Monspel. Sér. Bot. 10: 7-32.

Goldblatt P, Poston ME. 1988. Observations on the chromosome cytology of Velloziaceae. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 75: 192-195.

Gottsberger G. 1991. Pollination of some species of the Carludovicoideae, and remarks on the origin and evolution of the Cyclanthaceae. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 113: 221-235.

Grayum MH, Hammel BE. 1982. Three new species of Cyclanthaceae from the Caribbean lowlands of Costa Rica. – Syst. Bot. 7: 221-229.

Green PS, Solbrig O. 1966. Sciaphila dolichostyla (Triuridaceae). – J. Arnold Arbor. 47: 266-269.

Greves S. 1921. A revision of the Old World species of Vellozia. – J. Bot. 59: 273-284.

Ham RWJM van der. 1991. Pollen morphology of the Stemonaceae. – Blumea 36: 127-159.

Ham RWJM van der. 1994. Pollen morphology of the Stemonaceae and Pentastemonaceae. – Acta Bot. Gallica 141: 285-293.

Hammel BE. 1986. Notes on the Cyclanthaceae of southern Central America including three new species. – Phytologia 60: 5-15.

Hammel BE, Wilder GJ. 1989. Dianthoveus, a new genus of Cyclanthaceae. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 76: 112-123.

Harada I. 1947. Chromosome numbers in Pandanus, Sparganium and Typha. – Cytologia 14: 214-218.

Harborne JB, Williams CA, Greenham J, Eagles J. 1994. Variation in the phenolic and vacuolar flavonoids of the genus Vellozia. – Phytochemistry 35: 1475-1480.

Harling G. 1946. Studien über den Blütenbau und die Embryologie der Familie Cyclanthaceae. – Svensk Bot. Tidskr. 40: 257-272.

Harling G. 1958. Monograph of the Cyclanthaceae. – Acta Horti Berg. 18(1): 1-428.

Harling G. 1963. Notes on Venezuelan Cyclanthaceae. – Bol. Soc. Venez. Ci. Nat. 25: 59-69.

Harling G. 1972. Cyclanthaceae. – In: Maguire B & al. (eds), The botany of the Guayana highlands, Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 23: 107-114.

Harling G. 1973. 216. Cyclanthaceae. – In: Harling G, Sparre B (eds), Flora of Ecuador 1, Swedish Natural Science Research Council, Stockholm, pp. 1-48.

Harling G. Wilder GJ, Eriksson R. 1998. Cyclanthaceae. – In: Kubitzki K (ed), The families and genera of vascular plants III. Flowering plants. Monocotyledons. Lilianae (except Orchidaceae), Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 202-215.

Heel WA van. 1992. Floral morphology of Stemonaceae and Pentastemonaceae. – Blumea 36: 481-499.

Hemsley WB. 1895. Pandanaceae. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 30: 216-217.

Henrard JT. 1937. Velloziaceae americanae nonnullae novae vel minus cognita. – Blumea 2: 339-382.

Holm T. 1905. Croomia pauciflora, an anatomical study. – Amer. J. Sci. 20: 50-54.

Hotton CL, Leffingwell HA, Skvarla JJ. 1994. Pollen ultrastructure of Pandanaceae and the fossil genus Pandaniidites. – In: Kurmann MH, Doyle JA (eds), Ultrastructure of fossil spores and pollen, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, pp. 173-191.

Huynh K-L. 1974. La morphologie microscopique et la taxonomie du genre Pandanus I. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 94: 190-256.

Huynh K-L. 1979. La morphologie microscopique de la feuille et la taxonomie du genre Pandanus V. P. subg. Vinsonia et P. subg. Martellidendron 1. Partie systématique. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 100: 321-371.

Huynh K-L. 1980. La morphologie du pollen de Pandanus subg. Vinsonia (Pandanaceae) et sa signification taxonomique. – Pollen Spores 22: 173-189.

Huynh K-L. 1981. Pandanus kariangensis (sect. Martellidendron), une espèce nouvelle de Madagascar. – Bull. Mus. Natl. Hist. Nat., B, Adansonia, sér. II, 1: 37-55.

Huynh K-L. 1982. La fleur mâle de quelques espèces de Pandanus subg. Lophostigma (Pandanaceae) et sa signification taxonomique, phylogénique et évolutive. – Beitr. Biol. Pflanzen 57: 15-83.

Huynh K-L. 1983. The taxonomic significance of the anther structure in the genus Pandanus (Pandanaceae) with reference to Pandanus sect. Martellidendron. – Webbia 37: 141-148.

Huynh K-L. 1991a. The flower structure in the genus Freycinetia, Pandanaceae I. Potential bisexuality in the genus Freycinetia. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 112: 295-328.

Huynh K-L. 1991b. The flower structure in the genus Freycinetia, Pandanaceae II. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 114: 417-441.

Huynh K-L. 1991c. New data on the taxonomic position of Pandanus eydouxia (Pandanaceae), a species of the Mascarene Islands. – Bot. Helv. 101: 29-37.

Huynh K-L. 1995. A new species of Freycinetia (Pandanaceae) from the Society Islands. New subgenus and new sections. – Candollea 50: 231-245.

Huynh K-L. 1996. The genus Freycinetia (Pandanaceae) in New Guinea (part 1). – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 118: 529-545.

Huynh K-L. 1997. The genus Pandanus (Pandanaceae) in Madagascar 1. – Bull. Soc. Neuchâtel. Sci. Nat. 120: 35-44.

Huynh K-L. 1999a. The genus Pandanus (Pandanaceae) in Madagascar 4. – Bull. Soc. Neuchâtel. Sci. Nat. 122: 35-43.

Huynh K-L. 1999b. The genus Freycinetia (Pandanaceae) in New Guinea (part 2). – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 121: 149-186.

Huynh K-L. 2000a. The genus Pandanus (Pandanaceae) in Madagascar 5. – Bull. Soc. Neuchâtel. Sci. Nat. 123: 27-35.

Huynh K-L. 2000b. The genus Freycinetia (Pandanaceae) in New Guinea (part 3). – Candollea 55: 283-306.

Huynh K-L. 2001a. Contribution to the flower structure of Sararanga (Pandanaceae). – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 136: 239-245.

Huynh K-L. 2001b. The genus Freycinetia (Pandanaceae) in New Guinea (part 5). – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 123: 321-340.

Huynh K-L. 2002a. The genus Freycinetia (Pandanaceae) in New Guinea (part 4). – Blumea 47: 513-536.

Huynh K-L. 2002b. The genus Freycinetia (Pandanaceae) in New Guinea (part 6). – Candollea 57: 55-65.

Huynh K-L. 2002c. The genus Freycinetia (Pandanaceae) in New Guinea (part 7). – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 124: 151-161.

Huynh K-L. 2003a. The genus Freycinetia (Pandanaceae) in New Guinea (part 8). – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 125: 73-83.

Huynh K-L. 2003b. The genus Freycinetia (Pandanaceae) in New Caledonia (part 1). – Candollea 58: 297-304.

Huynh K-L. 2004. The genus Freycinetia (Pandanaceae) in New Caledonia (part 2). – Candollea 59: 175-180.

Huynh K-L, Cox PA. 1992. Flower structure and potential bisexuality in Freycinetia reineckei (Pandanaceae), a species of the Samoa Islands. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 110: 235-265.

Ibisch PL, Nowicki C, Vasquez R, Koch K. 2001. Taxonomy and biology of Andean Velloziaceae: Vellozia andina sp. nov. and notes on Barbaceniopsis (including Barbaceniopsis castillonii comb. nov.). – Syst. Bot. 26: 5-16.

Imhof S. 1998. Subterranean structures and mycotrophy of the achlorophyllous Triuris hyalina (Triuridaceae). – Can. J. Bot. 76: 2011-2019.

Imhof S. 2004. Morphology and development of the subterranean organs of the achlorophyllous Sciaphila polygyna (Triuridaceae). – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 146: 295-301.

Inthachub P, Vajrodaya S, Duyfjes BEE. 2009. review of the genus Stichoneuron (Stemonaceae). – Edinburgh J. Bot. 66: 213-228.

Jarzen DM. 1983. The fossil pollen record of the Pandanaceae. – Gard. Bull. (Singapore) 36: 163-175.

Jiang R-W, Hon P-M, Xu Y-T, Chan Y-M, Xu H-X, Shaw PC, But PP-H. 2006. Isolation and chemotaxonomic significance of tuberostemospironine-type alkaloids from Stemona tuberosa. – Phytochemistry 67: 52-57.

Kao P-C. 1980. A new genus of Amaryllidaceae from China. – Acta Phytotaxon. Chengdu Inst. Biol. Acad. Sin. 1: 1-3. [In Chinese and Latin]

Kao P-C. 1989. Acanthochlamydaceae – a new monocotyledonous family. – In: Kao P-C, Tan Z-M (eds), Flora of Sichuan 9, pp. 483-507. [In Chinese and English]

Kao P-C, Kubitzki K. 1998. Acanthochlamydaceae. – In: Kubitzki K (ed), The families and genera of vascular plants III. Flowering plants. Monocotyledons. Lilianae (except Orchidaceae), Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 55-58.

Kao P-C, Tang Y, Guo W-H. 1993. A cytological study of Acanthochlamys bracteata P. C. Kao (Acanthochlamydaceae). – Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 31: 42-44. [In Chinese with English summary]

Krause K. 1930. Stemonaceae. – In: Engler A (ed), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien, 2. Aufl., Bd. 15a, W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 224-227.

Kubitzki K. 1998a. Pentastemonaceae. – In: Kubitzki K (ed), The families and genera of vascular plants III. Flowering plants. Monocotyledons. Lilianae (except Orchidaceae), Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 404-406.

Kubitzki K. 1998b. Stemonaceae. – In: Kubitzki K (ed), The families and genera of vascular plants III. Flowering plants. Monocotyledons. Lilianae (except Orchidaceae), Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 422-425.

Kubitzki K, Smith LB. 1998. Velloziaceae. – In: Kubitzki K (ed), The families and genera of vascular plants III. Flowering plants. Monocotyledons. Lilianae (except Orchidaceae), Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 459-467.

Lachner-Sandoval V. 1892. Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Gattung Roxburghia. – Bot. Centralbl. 50: 65-70, 97-104, 129-135.

Laivao MO, Callmander MW, Wohlhauser S. 2000. Une espèce nouvelle de Pandanus sect. Martellidendron (Pandanaceae) de la péninsule de Masoala, Madagascar. – Bot. Helvetica 110: 41-49.

Laivao MO, Callmander MW, Buerki S. 2006. Sur les Pandanus (Pandanaceae) à stigmates saillants de la côte est de Madagascar. – Adansonia, sér. III, 28: 267-285.

Laivao MO, Callmander MW, Buerki S. 2007. Révision de Pandanus sect. Foullioya Warb. (Pandanaceae) à Madagascar. – Adansonia, sér. III, 29: 39-57.

Lam VKY, Gomez MS, Graham SW. 2015. The highly reduced plastome of mycoheterotrophic Sciaphila (Triuridaceae) is colinear with its green relatives and is under strong purifying selection. – Genome Biol. Evol. 7: 2220-2236.

Li E-X, Yi S, Qiu Y-X, Guo J-T, Comes HP, Fu C-X. 2008. Phylogeography of two East Asian species in Croomia (Stemonaceae) inferred from chloroplast DNA and ISSR fingerprinting variation. – Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 49: 702-714.

Li P, Gao B-C. 1993. Studies on morphology of Acanthochlamys bracteata III. The investigation on double fertilization, embryogenesis and endosperm development of Acanthochlamys bracteata. – J. Sichuan Univ. (Science ed.) 30: 260-263. [In Chinese with English summary]

Li P, Gao B-C, Chen F, Luo HX. 1992. Studies on morphology and embryology of Acanthochlamys bracteata II. The anther and ovule development. – Bull. Bot. Res. 12: 389-395. [In Chinese with English summary]

Maas PJM. 1988. Triuridaceae. – In: Pinto P, Lozano G (eds), Flora de Colombia, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, pp. 1-26.

Maas PJM, Rübsamen T. 1986. Flora Neotropica. Monograph 40. Triuridaceae. – New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York.

Maas-van de Kamer H. 1995. Triuridiflorae – gardner’s delight? – In: Rudall PJ, Cribb PJ, Cutler DF, Humphries CJ (eds), Monocotyledons: systematics and evolution, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, pp. 287-301.

Maas-van de Kamer H, Maas PJM. 1994. Triuridopsis, a new monotypic genus in Triuridaceae. – Plant Syst. Evol. 192: 257-262.

Maas-van de Kamer H, Weustenfeld T. 1998. Triuridaceae. – In: Kubitzki K (ed), The families and genera of vascular plants III. Flowering plants. Monocotyledons. Lilianae (except Orchidaceae), Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 452-458.

Mallik R, Sharma AK. 1966. Chromosome studies in Indian Pandanales. – Cytologia 31: 402-410.

Márquez-Guzmán J, Engelman EM, Martínez Mena A, Martínez E, Ramos C. 1989. Anatomia reproductiva de Lacandonia schismatica (Lacandoniaceae). – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 76: 124-127.

Márquez-Guzmán J, Vásquez-Santana S, Engleman EM, Martínez-Mena A, Martínez E. 1993. Pollen development and fertilization in Lacandonia schismatica (Lacandoniaceae). – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 80: 891-897.

Martelli U. 1913. Enumerazione delle ‘Pandanaceae’ II. Pandanus. – Webbia 4: 391-438.

Martelli U. 1929. The Pandanaceae collected for the Arnold Arboretum by L. J. Brass in New Guinea. – J. Arnold Arbor. 10: 137-142.

Martelli U. 1933. Notizie sul sottogenere Vinsonia e la posizione sistematica del Pandanus spinifer. – Atti Soc. Tosc. Sci. Nat. Pisa Processi Verbali 12: 55-57.

Martelli U, Pichi-Sermolli R. 1951. Les Pandanacées récoltées par Henri Perrier de la Bâthie à Madagascar. – Mém. Inst. Sci. Madagascar, sér. B, Biol. Vég. 3(1): 1-174.

Martinez E, Ramos CH. 1989. Lacandoniaceae (Triuridales): una nueva familia de México. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 76: 128-135.

Meerendonk JPM van de. 1984. Triuridaceae. – In: Steenis CGGJ van (ed), Flora malesiana I, 10(1), Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague, Boston, London, pp. 109-121.

Meijer W, Bogner J. 1983. Pentastemona (Stemonaceae): the elusive plant. – Nature Malaysiana 8(1): 26-27.