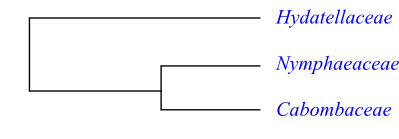

Phylogeny of Nymphaeales based on DNA sequence data. Trithuria (Hydatellaceae) is sister to [Nymphaeaceae+Cabombaceae] with a bootstrap support of 100%. Trithuria has ascidiate carpel development like other Nymphaeaceae.

[Nymphaeales+[Schisandrales+[[Chloranthaceae+Magnoliidae]+[Liliidae+[Ceratophyllum+Tricolpatae]]]]]

Hydropeltidopsida Bartl., Ord. Nat. Plant.: 78, 86. Sep 1830 [’Hydropeltideae’]; Hydropeltidales Spenn., Handb. Angew. Bot. 1: 202. 1-19 Jul 1834 [‘Hydropeltideae’]; Nymphaeopsida Horan., Prim. Lin. Syst. Nat.: 55. 2 Nov 1834 [’Nymphaeales’]; Cabombales Rich. in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp. Regn. Veg.: 38. Sep-Oct 1835 [‘Cabombeae’]; Euryalales H. L. Li in Amer. Midl. Naturalist 54: 39. 27 Aug 1955; Nymphaeanae Thorne ex Reveal in Novon 2: 236. 13 Oct 1992; Barclayales Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.: xxiii. 23 Dec 2001

Fossil Pluricarpellatia peltata is the oldest known fossil of presumably nymphaealean origin and was described from the Late Aptian to Early Albian (the Early Cretaceous, 125–115Mya) layers of Brazil. This probably aquatic species had peltate leaves and an apocarpous gynoecium. A number of fossil seeds, leaves and pollen are known from the Late Cretaceous of, e.g., Europe, North America, Israel, and Japan. There is also a vast fossil record of Nymphaeales from the Cenozoic of Portugal and eastern North America, consisting of leaves, roots, stems and reproductive organs including seeds. These can be assigned to extant groups as well as to the fossil Braseniella, Dusembaya, Eoeuryale, Irtyshenia, Nikitinella, Palaeoeuryale, Palaeonymphaea, Protobarclaya, Pseudoeuryale, Sabrenia, Tavdenia and Tomskiella.

Habit Usually bisexual (rarely monoecious or dioecious), usually perennial (rarely annual) herbs. Aquatic. Usually with a rhizome or tuberous stem (some species stoloniferous).

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza absent. Primary root ephemeral, replaced by adventitious roots, initiated from the nodes (single root arising from point below each leaf); proximal cell comparatively small; root cap enlarged; root cap and epidermis not of common ontogenetical origin; secondary dermatogen present in root apex; root epidermis with short cells alternating with long cells; root endodermis with casparian strips; root aerenchyma interrupted by diaphragms. Phellogen absent. Epidermis initiated from outer cortical layer. Primary stem with scattered closed vascular bundles; axial vascular bundles concentric. Stem vascular tissue complex near nodes. Development of primary xylem mesarch; primary xylem with tracheids (with annular, spiral or reticulate secondary cell wall thickenings) and protoxylem with lacunae. Cambium and secondary lateral growth absent. Vessels or vessel-like elements (primary protoxylem lacunae, present in root primary xylem) with complex to scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform, simple pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids with annular or spiral secondary cell wall thickenings and with simple pits. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids usually S type (sometimes P2c type). Nodes 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces, or 1:2, unilacunar with two traces, or more complex. Trichoblasts in vertical rows and articulated unbranched laticifers usually abundant. Sclerenchymatous idioblasts and sclereids present or absent; sclereids when present stellate to girdle- or H-shaped; asterosclereids with calciumoxalate crystals often frequent in cell walls. Starch grains complex. Tanniniferous parenchyma cells often abundant in rhizome. Silica probably absent.

Trichomes Hairs tricellular or quadricellular, uniseriate, simple, often as secretory mucilage hairs or nectariferous hairs with large terminal cell, hydropotes.

Leaves Alternate (spiral), simple, entire, peltate, or much divided (sometimes linear to filiform), usually with involute ptyxis, usually floating or submersed. Stipules adaxial and bicarinate, pairwise and lateral, or absent; leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle? Venation palmate, actinodromous, brochidodromous or semidichotomous. Stomata stephanocytic or anomocytic, only on adaxial side of leaf, or absent. Cuticular waxes absent. Mesophyll with sclerenchymatous idioblasts (asterosclereids present), with or without mucilage cells. Idioblasts with ethereal oils absent. Leaf margin serrate, sinuate or entire.

Inflorescence Flowers solitary, axillary or extra-axillary, often not in normal axillary position, alternating with leaves in foliar spiral or arising from separate spirals (sometimes terminal, capitate, bisexual pseudanthia surrounded by membranous bracts, with central male flowers surrounded by female flowers). Bracts usually absent.

Flowers Actinomorphic. Hypanthium usually present. Hypogyny to epigyny. Tepals spiral or whorled, with imbricate aestivation, usually free (sometimes absent), at least inner ones probably extrastaminal staminodia; outer (two to) four to six (to twelve) tepals sepaloid to petaloid; inner two to more than 70 tepals (sometimes absent) usually petaloid staminodia with nectaries (nectaries rarely spur-like or absent). Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens 14 to more than 200, spiral or whorled, usually broad, three-veined, free, outwards and inwards often grading into staminodia (stamens rarely with narrow filaments). Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, usually introrse (sometimes latrorse, rarely extrorse), longicidal (dehiscing usually with longitudinal slits, sometimes H-shaped). Tapetum usually secretory or amoeboid-periplasmodial. Staminodia often numerous.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis usually simultaneous (rarely successive). Pollen grains globose or boat-shaped, usually zonasulculate (with band-shaped aperture encircling equator; sometimes anasulcate; rarely inaperturate? or anatrichotomocolpate), usually shed as monads (in ’Victoria clade’ of Nymphaea as tetrads), bicellular or tricellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with granular, intermediary or columellate infratectum, perforate, microperforate, scabrate or striate, spinulate, verrucate, echinulate or psilate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (one or) three to c. 35 conduplicate carpels, whorled, free or partially or entirely connate; carpel usually ascidiate (rarely plicate or intermediary), postgenitally occluded by secretion, with secretory canal; extragynoecial compitum probably absent; carpels usually with uniseriate hairs with tanniniferous elongate terminal cell. Ovary superior to inferior, usually multilocular (sometimes unilocular). Style transformed into carpellary appendages, or single, or absent. Stigmas usually capitate, with receptive surfaces radiating from centre (rarely deeply decurrent, sometimes penicillate consisting of hairs), papillate (with multicellular papillae) or non-papillate, usually Wet (sometimes Dry) type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation usually laminar (sometimes apical). Ovules (one to) numerous per carpel, usually anatropous, pendulous (rarely orthotropous, horizontal), bitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal to bistomal. Nucellar cap sometimes present. Megagametophyte monosporous, quadrinucleate and quadricellular, Nuphar/Schisandra type. Antipodal cells absent. A single uninucleate haploid central cell. The two nuclei after first division present at micropylar pool. Egg cell differentiated from one of the three micropylar cells after second division. One sperm nucleus and one polar nucleus fusing during second fertilization. Endosperm development usually cellular (rarely helobial or nuclear). Endosperm cells diploid. Endosperm haustorium chalazal. Embryogenesis asterad.

Fruit Usually a berry-like capsule with fleshy spongy tissue, dehiscing dorsally to irregularly (sometimes an achene-like follicle; rarely an assemblage of achenes).

Seeds Funicular aril usually present. Operculum dehiscent at germination, present at micropylar end. Seed coat exotestal. Exotesta often palisade. Mesotesta and endotesta unspecialized. Tegmen usually unspecialized. Perisperm well developed, usually copious, starchy, containing multinucleate cells with compound starch grains, or absent. Endosperm scarse, little developed, enclosing embryo at micropylar end. Embryo small, slightly triangular to broad, with or without chlorophyll. Suspensor absent. Cotyledons (one or) two, more or less fused. Germination phanerocotylar or cryptocotylar. Radicula ephemeral. Seedlings and young plants monopodial, with linear first leaves.

Cytology n = 10, 12, 14–112

DNA An intergenic inversion of c. 200 bp is present in the plastid inverted repeat (IR region). Exon 5’ in PI-homologues 42 bp, at least in Nymphaeaceae (ancestral character state among angiosperms).

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), flavone-C-glycosides, ellagic and gallic acid, hydrolyzable gallo- and ellagitannins (ellagitannins different from those occurring elsewhere), proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins etc.), and special sulphuric sesquiterpene pseudoalkaloids present.

Systematics Nymphaeales and Schisandrales both have a quadrinucleate and quadricellular megagametophyte comprising a tricellular egg apparatus and a central cell with a single haploid polar nucleus at maturity (Friedman & Ryerson 2008). The two nuclei resulting from the first mitotic division of the single functional megaspore do not migrate to opposite regions of the developing megagametophyte, but remain at the micropylar pole. A second division produces four micropylar megagametophyte nuclei and the egg cell develops from one of these nuclei during the differentiation of the three-celled egg apparatus. The fourth cell forms the nucleus of the central cell and the endosperm resulting from the double fertilization becomes diploid.

Hydatellaceae (Trithuria) is sister to the clade [Nymphaeaceae+Cabombaceae]. Cabombaceae and Nymphaeaceae have rhizome. The tracheid end walls are provided with a unique reticulate fibrillar structure (at least in species of Nuphar and Nymphaea). The peltate leaves have an involute ptyxis (vernation) and palmate actinodromous or brochidodromous secondary veins. The flowers are borne singly on usually long scapes along the stem and possess a cortical vascular tissue. The tepals and stamens are whorled and the outer tepals enclose the remaining bud. The carpel margins are postgenitally fused and placentation is laminar. The exotesta is palisade and the anticlinal testal cell walls are sinuate.

The presence of hydropotes is a synapomorphy of at least Cabombaceae and Nymphaeaceae. It is not known whether they occur also in Trithuria (Hydatellaceae). Hydropotes are gland-like cellular structures on the abaxial leaf surface, responsible for the uptake of nutrients and water. A hydropote consists of a caducous unicellular or multicellular uniseriate portion which is abscised when mature, and a basal row of three or four partially overlapping epidermal cells (Carpenter 2006). In Cabombaceae the hydropotes are secretory with one or two terminal mucilaginous hair cells on top of two discoid cells and below these a basal foot cell. Carpenter (2006) interprets these structures as homologous with, e.g., (actinocytic/stephanocytic) stomata present in Amborella and Trimenia and the epidermal ethereal oil cell complexes of Schisandrales. Intermediates between true stomata, oil cell complexes and hydropotes are sometimes present.

|

Phylogeny of Nymphaeales based on DNA sequence data. Trithuria (Hydatellaceae) is sister to [Nymphaeaceae+Cabombaceae] with a bootstrap support of 100%. Trithuria has ascidiate carpel development like other Nymphaeaceae. |

CABOMBACEAE Rich. ex A. Rich. |

( Back to Nymphaeales ) |

Hydropeltidaceae (DC.) Dumort., Comment. Bot.: 64. Nov-Dec 1822 [’Hydropeltideae’]

Genera/species 2/6

Distribution Cabomba: tropical, subtropical and temperate parts of North and South America; Brasenia: tropical, subtropical and temperate parts of North and Central America, the West Indies, Africa, East Asia (China, the Korean Peninsula, Taiwan, Japan, Manchuria), northern India, and northeastern and southeastern Australia.

Fossils Cabombaceae are known from the Early Cretaceous. Pluricarpellatia peltata is a Late Aptian to Early Albian Brazilian fossil with apocarpous gynoecium, suggesting affinity with Cabombaceae. Subfossils of Brasenia schreberi are described from a large number of localities in Europe and other parts of the Northern Hemisphere, and fossil leaves (Braseniopsis) resembling Brasenia are known from the Early Cretaceous of Portugal. Scutifolium jordanicum (Albian of Jordan) consists of peltate small leaves similar to Cabomba.

Habit Bisexual, perennial herbs. Aquatic, with rhizome and usually floating stem; submersed organs of Brasenia covered by a gelatinous layer (absent in Cabomba). Leaves of Brasenia isomorphous (monomorphous), in Cabomba anisomorphous (dimorphous).

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza absent. Primary root ephemeral, replaced by adventitious roots, initiated from nodes (a single root arising from a point below each leaf); proximal cell comparatively small?; root cap enlarged?; secondary dermatogen present in root apex; root epidermis with short cells alternating with long cells; root endodermis with casparian strips and suberine lamels?; root aerenchyma interrupted by diaphragms. Phellogen absent. Epidermis initiated from outer cortical layer. Aerenchyma abundant. Stem with air canals and one to four vascular bundles (single or pairwise, collateral). Primary stem with scattered closed vascular bundles. Development of primary xylem mesarch? Axial vascular bundles concentric. Secondary lateral growth and cambium absent. Vessel elements (in Brasenia present in roots and stems; in Cabomba only in stems) – primary protoxylem lacunae – with perforation plates provided with series of pores or sometimes scalariform; tracheid end walls with reticulum of coarse fibrils; lateral cell wall thickenings annular to helical to scalariform (in root vessels unlignified), often inconspicuous, simple pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids with annular or spiral secondary cell wall thickenings and with simple pits. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids S type, with approx. ten starch grains. Sieve tube elements of primary phloem with almost transverse end walls and simple sieve plates. Nodes 1:2, unilacunar with two leaf traces; node anatomy difficult to interpret; in Cabomba one leaf trace initiated from each pair of vascular bundles, these immediately united commissurally and forming a nodal plexus. Laticifers present. Sclerenchymatous idioblasts and sclereids absent. Stems in Brasenia covered by thick mucilaginous layer. Starch grains complex. Prismatic calciumoxalate crystals often present in epidermal cells.

Trichomes Hairs tricellular or quadricellular, uniseriate, simple, in the form of secretory mucilage hairs, hydropotes, with a large terminal cell (in Brasenia).

Leaves Floating leaves in Brasenia alternate (spiral), simple, entire, usually peltate, with involute ptyxis, actinodromous venation, stomata and entire margin; specialized submerged leaves absent. Floating leaves in Cabomba alternate (spiral) or opposite (rarely verticillate), simple, entire or bifurcate, usually peltate, with involute ptyxis, actinodromous venation, stomata and entire margin (floating leaves few, developed at anthesis); specialized submersed leaves five- to seven-dissected, with each foliar part dichotomously or trichotomously branched, with stomata at margins near vein ends. Stipules adaxial bicarinate, pairwise lateral, or absent; leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle? Venation palmate, semidichotomous. Stomata stephanocytic or anomocytic, only on adaxial side of leaf, or absent. Cuticular waxes absent. Mesophyll with or without mucilage cells. Idioblasts with ethereal oils absent. Thin-walled spherical crystalliferous processes similar to oil cells often present on adaxial epidermis.

Inflorescence Flowers axillary or extra-axillary (arising laterally relative to leaf, with common vascular tissue), solitary (reduced raceme).

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Hypogyny. Outer tepals (two or) three (or four), sepaloid, whorled, free (Brasenia) or connate at base (Cabomba); inner tepals (two or) three (or four), petaloid, whorled, free (Brasenia) or connate at base (Cabomba), with retarded development; tepals probably staminodial. Nectariferous spurs in Cabomba two adaxial at base of inner petaloid tepals; nectary absent in Brasenia. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens three or six (Cabomba), or 18 to 36 (Brasenia), spiral or whorled. Filaments filiform, free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, latrorse (Brasenia) or extrorse (Cabomba), longicidal (dehiscing with longitudinal slits). Tapetum amoeboid-periplasmodial (Cabomba), with migratory tapetal cells in direct contact with developing free microspores within anther locule. Staminodia intra- or extrastaminal.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous (Brasenia) or successive (Cabomba). Pollen grains boat-shaped, anasulcate (in Cabomba sometimes anatrichotomocolpate), shed as monads, bicellular (Cabomba) or tricellular (Brasenia) at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum, microperforate or scabrate (with rods, Brasenia) or striate (Cabomba); endexine not lamellate, initiated as plates.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (one or) three (to seven) (Cabomba) or four to 19 (Brasenia) carpels, whorled, free (in Cabomba rarely connate at base); carpel ascidiate, with margins apparently occluded by secretion (carpel margins not fused). Ovary superior, unilocular (apocarpy). Style single, simple, short (Brasenia) or long (Cabomba). Stigma capitate (Cabomba) or deeply decurrent (Brasenia), papillate, Dry type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation laminar-dorsal or laminar-median. Ovules usually two or three (sometimes one, four or five) per carpel, anatropous, pendulous, bitegmic, weakly crassinucellar. Micropyle endostomal (to bistomal?). Outer integument in Cabomba two, in Brasenia two to four cell layers thick. Inner integument two cell layers thick. Hypostase present. Megagametophyte in Cabomba (and Brasenia?) monosporous, quadricellular, Nuphar/Schisandra type. Antipodal cells ephemeral (Brasenia) or absent (Cabomba). Pollen tubes growing directly into dense substigmatic ground tissue subsequently reaching stylar canal through breakdown of mid-lamellae. Suspensor absent (proembryo with suspensor). Endosperm development helobial (first division transversal, micropylar cell free nuclear, chalazal cell enlarged). Endosperm haustorium chalazal. Embryogenesis asterad?

Fruit An assemblage of achenes (Brasenia) or dorsally dehiscent follicle-like fruits (Cabomba).

Seeds Aril absent. Operculum at micropylar end. Hilum and micropyle with common opening in centre of operculum. Seed coat mainly exotestal. Exotesta palisade, with sinuous anticlinal cell walls. Sclerotesta in Brasenia with very thick outer periclinal and anticlinal cell walls. Mesotesta and endotesta unspecialized. Tegmen unspecialized. Perisperm well developed, with multinucleate cells, starchy; starch grains compound. Endosperm sparse, little developed, enclosing embryo at micropylar end. Embryo small, slightly triangular, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar? Radicula ephemeral.

Cytology n = 40 (Brasenia); n = 48, 52 (Cabomba)

DNA Intergenic inversion present in plastid IR?

Phytochemistry Hydrolyzable gallo- and ellagitannins (in Brasenia) present. Mucilage in Brasenia containing glucuronic acid, galactose, rhamnose, etc. Alkaloids not found.

Use Aquarium plants, vegetables.

Systematics Brasenia (1; tropical, subtropical and temperate parts of North and Central America, the West Indies, Africa, China, the Korean Peninsula, Taiwan, Japan, Manchuria, northern India, northeastern and southeastern Australia), Cabomba (5; C. aquatica, C. caroliniana, C. furcata, C. haynesii, C. palaeformis; tropical, subtropical and temperate parts of North and South America).

Cabombaceae are sister-group of Nymphaeaceae.

The vessel elements probably evolved in parallel in Nymphaeaceae and Cabombaceae (Schneider & Carlquist 1996).

HYDATELLACEAE U. Hamann |

( Back to Nymphaeales ) |

Hydatellales Cronquist in Takhtajan, Bot. Rev. (Lancaster) 46: 317. 1980; Hydatellanae Takht. ex Reveal in Novon 2: 236. 13 Oct 1992

Genera/species 1/12

Distribution Western India, coastal areas in northern, southwestern and southern Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Usually monoecious (rarely dioecious), usually annual (rarely perennial) very small herbs. Caespitose aquatic and marsh plants. Trithuria inconspicua may flower at a depth of more than one metre.

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza absent. Primary root early aborted, replaced by endogenous adventitious roots; air canals absent from roots and replaced by endodermis cells with large vacuoles. Phellogen absent. Epidermis initiated from outer cortical layer? Vessels – primary protoxylem lacunae – present in roots. Secondary lateral growth and cambium absent. Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pitting? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements? Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma absent? Sieve tube plastids P2c type, with cuneate protein crystals, without starch or protein filaments. Nodes 1:1 (unilacunar with one leaf-trace)? Laticifers absent. Mucilage cells absent. Sclerenchyma absent. Calciumoxalate and silica probably absent.

Trichomes Eglandular hairs at stem bases only, axillary, uniseriate, multicellular (sometimes absent); glandular hairs (hydropotes?) with one to three basal cells and one elongate terminal (secretory?) cell present between flowers.

Leaves Alternate (spiral), simple, entire, linear to filiform, often in a basal rosette, with ? ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole one-veined. Leaf with schizogenous air canal. Vein single, simple. Stomata anomocytic or absent. Cuticular waxes Strelitzia type or absent. Leaf margin entire. Vorläuferspitze (fore-runner point, apical precursor point) absent.

Inflorescence Terminal, capitate, cymose pseudanthia (possibly thyrse), surrounded by usually two or four (sometimes three or five, rarely six to eight) opposite, membranous, linear to tepaloid bracts. Inflorescence usually bisexual, with central centrifugally initiated male flowers surrounded by centrifugally initiated female flowers. Inflorescence hairs (hydropotes?) multicellular, with elongate (perhaps secretory) terminal cell. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) two, transversal (one of them sometimes undeveloped).

Flowers Actinomorphic, very small. Tepals absent. Pedicel at least sometimes articulated. Nectaries absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamen one. Filaments filiform. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, latrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum? Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains boat-shaped, usually monosulcate (or indistinctly monoporate; occasionally trichotomosulcate), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum, perforate, usually microechinate (sometimes striate).

Gynoecium Pistil composed of one in transverse section triangular carpel (or primarily three carpels forming a pseudomonomerous gynoecium); carpel ascidiate; carpel margins probably not fused (carpel seemingly ’closed’ by two compressed but not fused surfaces), at anthesis with a very short narrow canal. Closure by transverse slit occurring together with longitudinal slit. Ovary superior?, unilocular, briefly stipitate. Style absent. Stigma penicillate, consisting of two to ten uniseriate multicellular hairs, Dry type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation apical. Ovule one per ovary, anatropous, apotropous, pendulous (with erect micropyle), bitegmic, pseudocrassinucellar or incompletely tenuinucellar. Micropyle bistomal. Outer integument two cell layers thick. Inner integument two cell layers thick. Nucellar cap ephemeral, formed by apical epidermis of megasporangium. Perisperm present outside megagametophyte in unfertilized ovules. Megagametophyte monosporous, quadrinucleate and probably quadricellular, Nuphar/Schisandra type; antipodal cells ephemeral or absent. Two megagametophytes often present in one and the same ovule (possibly developed from different megaspores in tetrad). Endosperm development ab initio cellular. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A one-seeded, thin-walled achenoid indehiscent follicle or a dehiscent follicle, dehiscing by three valves separating from three ribs. A single pericarp layer (exocarp) with except in regions adjacent to vascular bundles and at base and apex.

Seeds Aril absent. Operculum at micropylar end, with thickened tegmic cells (those adjacent to embryo strongly expanding during seedling growth). Seed coat mainly exotestal. Testa membranous, consisting of exotesta. Exotesta palisade; anticlinal cell walls not sinuous. Endotesta and exotegmen collapsing. Endotegmen tanniniferous. Perisperm well developed, rich in starch, formed subdermally from multicellular chalazal part of megasporangium. Endosperm few-celled, almost absent. Suspensor weakly developed or absent. Embryo small, peripheral, little differentiated, covered by operculum consisting of apical cells of inner layer of inner integument, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two, free from each other or fused through a leaf-like organ. Hypocotyl with collar rhizoids at base (rhizoids consisting of collar cells), developing asymmetrically. Germination cryptocotylar. Radicula ephemeral.

Cytology n = ? Agamospermy possibly occurring in Trithuria filamentosa.

DNA

Phytochemistry Virtually unknown. Tannins present.

Use Unknown.

Systematics Trithuria (12; western India, coastal areas in northern, southwestern and southern Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand; T. konkanensis: western India; T. inconspicua: New Zealand; probably overlooked).

Trithuria (Hydatellaceae) is sister to the clade [Nymphaeaceae+Cabombaceae].

Trithuria shares numerous characters with especially Cabombaceae, but also Nymphaeaceae, several of which being unknown in Cyperales to which Hydatellaceae were formerly assigned. However, a number of these features also occur in different monocot clades. Cambium and pericyclic sclerenchyma are absent. The multicellular and probably secretory hairs present between stamens and carpels in Trithuria may be comparable to similar hairs in flowers of Brasenia. The stomata are anomocytic. The pollen grains are monosulcate and boat-shaped. The carpel is ascidiate, almost actinomorphic and similar to the early stages of the carpel in Cabomba. The ovule is anatropous and the megagametophyte develops according to the four-nucleate Nuphar/Schisandra type. The endosperm development is cellular. The exotesta is palisade and the outer integument is semi-annular (annular in, e.g., Barclaya). A seed operculum is formed by the enlargement of cells in the two-layered inner integument. The perisperm is usually early developed and rich in starch and the perisperm cells become multinucleate during their development. Also the weakly differentiated embryo in Trithuria is similar to certain Nymphaeales, having either a single cotyledon or possibly two fused cotyledons.

On the other hand, Trithuria has sieve tube plastids of P2c type (instead of S type as in Nymphaeaceae and Cabombaceae) and the leaves are linear. The ovule is tenuinucellar or pseudocrassinucellar (instead of crassinucellar). P2c type plastids also occur in Asaraceae (Asarum and Saruma). The linear leaves concentrated in a basal rosette and other superficial similarities between Trithuria and many monocotyledons – Cyperales in particular – may be due to adaptations to identical aquatic environments. The linear leaves in Trithuria resemble the first leaves of the seedling in Nymphaeaceae.

The inflorescence and flowers of Trithuria have been interpreted in several different ways. Is the gynoecium represented by a single ascidiate carpel or a pseudomonomerous pistil? The inflorescence consists of bracts which surround gynoecium and/or androecium, in bisexual units with the carpels outside the stamens. According to the interpretation by Rudall & al. (2007), the reproductive unit is an assemblage of apetalous unisexual flowers, each pistil thus corresponding to a solitary carpel.

In most species of Trithuria a bilobate membranous sheath (adnate to the testa) surrounds the main axis below the first seedling leaf. This sheath (reduced to a short outgrowth in some species) has been interpreted as homologous with the two connate cotyledons in Nymphaeaceae.

NYMPHAEACEAE Salisb. |

( Back to Nymphaeales ) |

Barclayaceae (Endl.) H. L. Li in Amer. Midl. Naturalist 54: 40. 27 Aug 1955; Euryalaceae J. Agardh, Theoria Syst. Plant.: 51. Apr-Sep 1858 [’Euryaleae’]; Nupharaceae A. Kern., Pflanzenleben 2: 699. 6-13 Jun 1891

Genera/species 3/70–90

Distribution Almost cosmopolitan.

Fossils Nymphaeaceae were previously much more diverse. Fossil Nymphaeaceae, flowers, seeds and leaf impressions, are known from Early Cretaceous (Turonian, c. 90 Mya) layers of, e.g., New Jersey. Monetianthus mirus is a 2 mm wide bisexual floral structure from the Late Aptian to the Early Albian of Portugal. Microvictoria svitkoana from the Early Cretaceous (possibly a species of Nymphaeaceae) may have belonged in the Nymphaeales stem group (Gandolfo & al. 2004). Its flowers are very similar to those in extant “Victoria” except for being approx. one tenth the size of the flowers in modern species. In “Victoria” the gynoecium is surrounded by ‘paracarpels’ also occurring in Microvictoria. The late Early Cretaceous aquatic Jaguariba wiersemana has been described from northeastern Brazil. Maastrichtian pollen grains of probable nymphaeacean origin have been found in Canada.

Habit Bisexual, usually perennial (rarely annual) herbs. Aquatic. Usually with rhizome or tuberous stem (some species of Nymphaea stoloniferous).

Vegetative anatomy Mycorrhiza absent. Radicula ephemeral, replaced by adventitious roots, initiated from nodes (one root arising from a point below each leaf). Proximal cell comparatively small; root cap enlarged; root apex with secondary dermatogen; root epidermis with short cells alternating with long cells; root endodermis with casparian strips; root aerenchyma interrupted by diaphragms. Inner root epidermis absent. Phellogen absent? Medulla of primary stem, rhizome, sometimes septate through diaphragms (with sclereids). Epidermis initiated from outer cortical layer. Rhizome with scattered closed vascular bundles; axial vascular bundles concentric. Stem vascular tissue complex near nodes. Maturation of primary xylem mesarch; primary xylem with tracheids (with annular, spiral or reticulate secondary cell wall thickenings) and protoxylem with lacunae. Secondary lateral growth and cambium absent. Vessels or vessel-like elements present in root primary xylem; vessel elements – primary protoxylem lacunae – with complex to scalariform perforation plates; pit membranes of root and stem tracheid end walls composed of coarse fibrils forming a meshwork (at least in Nuphar and some species of Nymphaea); lateral cell wall thickenings annular, helical or scalariform, simple pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids with simple pits. Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma? Sieve tube plastids S type, with approx. ten starch grains. Nodes 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces. Trichoblasts in vertical rows and articulated unbranched laticifers abundant. Sclereids stellate to girdle- or H-shaped; asterosclereids with calciumoxalate crystals frequent in cell walls at least in Nuphar and Nymphaea, and also occurring in Barclaya. Starch grains complex. Tanniniferous parenchyma cells often abundant in rhizome.

Trichomes Hairs quadricellular, uniseriate, simple, on young organs often secretory (mucilaginous or nectariferous hairs) with large terminal cell, hydropotes.

Leaves Alternate (spiral), simple, entire, peltate or divided, with involute ptyxis, usually floating or submersed. Stipules adaxial and bicarinate or pairwise and lateral (Nymphaea), or absent (Nuphar, Barclaya); leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle? Venation palmate, actinodromous, brochidodromous. Stomata stephanocytic or anomocytic, on adaxial side of leaf only. Cuticular waxes absent. Mesophyll with sclerenchymatic idioblasts; asterosclereids present. Idioblasts with ethereal oils absent. Leaf margin serrate, sinuous or entire (in “Victoria amazonica” bent upwards by c. 90º).

Inflorescence Flowers axillary or extra-axillary, often not in normal axillary position, solitary (reduced raceme), with often very long pedicel, alternating with leaves in leaf spiral (Nuphar, Nymphaea, “Ondinea”) or arising from separate spirals from leaves (in the “Euryale” and “Victoria clades” of Nymphaea). Floral pherophylls (bracteoles and bracts) present in Nuphar.

Flowers Actinomorphic, often very large. Hypanthium usually present (absent in Nuphar). Hypogyny to epigyny. Tepals spiral, with imbricate aestivation, free (absent in some species of “Ondinea”), at least inner ones probably extrastaminal staminodia; outer (two to) four to six (to twelve) tepals sepaloid to petaloid; inner two to more than 70 tepals (rarely absent) usually petaloid staminodia with nectaries. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamens 14 to more than 200, spiral or whorled, foliaceous, three-veined, free, outwards and inwards often grading into staminodia. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, usually introrse (rarely latrorse), longicidal (dehiscing usually with longitudinal slits, in Nuphar H-shaped); connective present or absent. Tapetum usually secretory (in Nuphar amoeboid-periplasmodial). Staminodia often numerous.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually globose (in Nuphar boat-shaped), usually zonasulculate (with band-like aperture encircling equator; in Nuphar anasulcate; in Barclaya inaperturate), usually shed as monads (in the “Victoria clade” of Nymphaea as tetrads), tricellular (or bicellular?) at dispersal. Exine tectate, with granular to intermediary infratectum; tectum in Nymphaea psilate, spinulate or verrucate, in Nuphar and the “Euryale clade” of Nymphaea echinulate or spinulate, in Barclaya psilate or scabrate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of three to c. 35 conduplicate carpels, whorled, laterally partially or entirely connate (receptacle often intruding into centre); carpel usually ascidiate (in Barclaya plicate to intermediate due to expanding central floral parts), postgenitally fused, with secretory canal; extragynoecial compitum present in Nymphaea. Ovary superior to inferior, plurilocular. Style absent or (in Barclaya and most species of Nymphaea) transformed into carpellary appendages. Stigma capitate, papillate (with unicellular or multicellular papillae), in Nuphar Wet and in Nymphaea usually Wet type (in the “Victoria” and “Euryale clades” and in Barclaya Dry type), with receptive surfaces radiating from centre (either on expanded apical disc or along cupular ovary surface; in Barclaya as indistinct radial disc with central conical appendage).

Ovules Placentation laminar-diffuse. Ovules (three to) numerous per carpel, usually anatropous, pendulous (in Barclaya orthotropous, horizontal and radially-laterally arranged), bitegmic, crassinucellar (in Barclaya weakly crassinucellar). Micropyle bistomal or endostomal. Outer integument cupular, two to numerous cell layers thick (in Barclaya two; in the “Euryale clade” of Nymphaea up to c. 20 cell layers thick). Inner integument two cell layers thick. Chalaza sometimes pachychalazal. Nucellar cap present in Nuphar. Megagametophyte monosporous, quadrinucleate, Nuphar/Schisandra type. Pollen tubes growing through short substigmatic zone, consisting of fused ground tissue, prior to reaching stylar canal. Endosperm development usually cellular (in some species of Nymphaea helobial; in the “Euryale clade” of Nymphaea nuclear). Endosperm haustorium chalazal. Embryogenesis asterad.

Fruit A berry-like capsule with fleshy spongy tissue, dorsally to irregularly dehiscing by expansion of mucilage in ovary locules.

Seeds Seeds in Nymphaea with funicular aril (absent in Barclaya and Nuphar) and at micropylar end an apical hood-shaped operculum dehiscing at germination; hilum present outside operculum. Seed coat exotestal. Exotesta often palisade (in Barclaya with special hairs), with sinuous anticlinal cell walls. Mesotesta and endotesta unspecialized. Tegmen unspecialized. Perisperm well developed, usually copious, with multinucleate cells, with compound starch grains, or absent. Endosperm scarce, little developed, enclosing embryo at micropylar end. Suspensor absent. Embryo small, wide, slightly triangular, well differentiated, with or without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, thick and fleshy, often fused. Germination phanerocotylar. Radicula ephemeral.

Cytology Barclaya, Nuphar: n = 17, 18; Nymphaea: n = (10–)14–112 (“Victoria clade”: n = 10, 12; “Euryale clade”: n = 29) – Polyploidy occurring at least in Nymphaea.

DNA An intergenic inversion of c. 200 bp is present in the plastid inverted repeat.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin), flavone-C-glycosides, ellagic and gallic acid, hydrolyzable gallo- and ellagitannins (unique ellagitannins in Nuphar, Nymphaea), proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidins etc.), and special sulphuric sesquiterpene pseudoalkaloids present. Benzylisoquinoline alkaloids?

Use Ornamental plants, aquarium plants (Barclaya longifolia etc.), edible seeds.

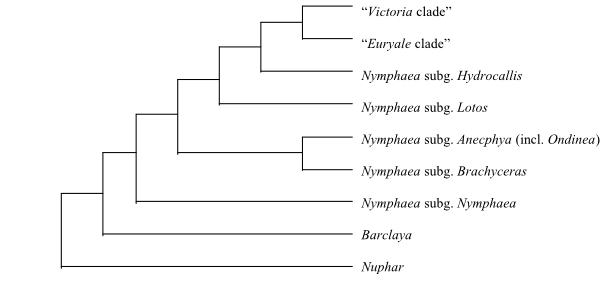

Systematics Nymphaeaceae are sister-group of Cabombaceae and Nuphar is sister to the clade [Barclaya+Nymphaea]. Barclaya is sister to an extended Nymphaea.

Nuphareae Endl., Gen. Plant.: 900. Nov 1839 [‘Nupharinae’]

Nuphar (c 20 [7–25]; North America, Europe, East Asia). – Roots with ten to 18 xylem poles. Pith extensive. Petiole and pedicel with numerous narrow air canals. Hypogyny. Outer (sepaloid) tepals five to 14, spiral. Distal part of gynoecium forming a more or less flattened disc with rays of stigmatic tissue. Stamens numerous. Staminodia absent. Pollen grains spinulate. Carpels five to 23 (to 30). Seeds non-arillate.

Nymphaeeae DC., Syst. Nat. 2: 43, 48. late Mai 1821

2/55–70. Nymphaea (c 50–65; almost cosmopolitan; “Ondinea clade“: northern Western Australia; “Victoria clade“: northern and central South America; “Euryale clade“: northern India, China, Japan), Barclaya (4; B. kunstleri, B. longifolia, B. motleyi, B. rotundifolia; Southeast Asia, Malesia). – Roots with five to nine xylem poles. Pith not extensive. Petioles and pedicels in Nymphaea s.lat. with few wide (in Barclaya numerous narrow) air canals. Inner satellite peduncular vascular bundle present. Epigyny or half epigyny. Outer (sepaloid) tepals (three or) four (or five), spiral. Stamens (14 to) numerous. Staminodia well developed, large, showy, or absent. Pollen grains zonasulcate (to inaperturate), with various supratectal sculpturing (filaments in the “Euryale clade” of Nymphaea thin and adnate at base to staminodia). Carpels (three to) eight to numerous. Stigmatic surface continuous. Placentation usually laminar. Ovules in Barclaya orthotropous. Fruits ripening below water surface. Seeds arillate (seeds in Barclaya echinate, non-arillate; exotestal cells in the “Euryale clade” of Nymphaea cuboid). x = 10, 12, 14–18. Polyploidy occurring. – The aril in Nymphaea has evolved into a floating device for the seed.

|

Cladogram of Nymphaeaceae based on DNA sequence data and morphology (Les & al. 1999; Löhne & al. 2007; Borsch & al. 2008). The former genera Euryale, Ondinea and Victoria are nested deep inside Nymphaea. |

Literature

Alaux M. 2011. Cabomba as a model for studies of early angiosperm evolution. – Ann. Bot. 108: 589-598.

Batygina TB, Shamrov II. 1983. Embryology of the Nelumbonaceae and Nymphaeaceae: pollen grain structure. – Bot. Žurn. 68: 1177-1183. [In Russian]

Batygina TB, Kravtsova TI, Shamrov II. 1980. Comparative embryology of some representatives of the orders Nymphaeales and Nelumbonales. – Bot. Žurn. 65: 1071-1087. [In Russian]

Batygina TB, Shamrov II, Kolesova GE. 1982. Embryology of the Nymphaeales and Nelumbonales II. Development of the female embryonic structures. – Bot. Žurn. 67: 1179-1195. [In Russian]

Beal EO. 1958. Taxonomic revision of the genus Nuphar Sm. of North America and Europe. – J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 72: 317-346.

Borsch TS. 2000. Phylogeny and evolution of the genus Nymphaea (Nymphaeaceae). – Ph.D. diss., Friedrich-Wilhelms Universität, Bonn, Germany.

Borsch TS, Soltis PS. 2008. Nymphaeales – the first globally diverse clade? – Taxon 57: 1051.

Borsch TS, Hilu KW, Wiersema JH, Löhne C, Barthlott W, Wilde V. 2007. Phylogeny of Nymphaea (Nymphaeaceae): evidence from substitutions and microstructural changes in the chloroplast trnT-trnF region. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 168: 639-671.

Borsch TS, Löhne C, Wiersema JH. 2008. Phylogeny and evolutionary patterns in Nymphaeales: integrating genes, genomes and morphology. – Taxon 57: 1052-1081.

Bruggen HWE van. 1961. Barclaya motleyi Hooker f. – Het Aquarium 33: 6-8.

Bruggen HWE van. 1968. Cabomba-soorten. – Het Aquarium 38: 152-156.

Bukowiecki H, Furmanowa M, Oledzka H. 1972. The numerical taxonomy of Nymphaeaceae Bentham et Hooker I. Estimation of taxonomic distance. – Acta Pol. Pharm. 29: 319-327.

Bukowiecki H, Furmanowa M, Oledzka H. 1974. The numerical taxonomy of Nymphaeaceae Bentham et Hooker II. Estimation of similarity coefficients. – Acta Pol. Pharm. 31: 385-391.

Capperino ME, Schneider EL. 1985. Floral biology of Nymphaea mexicana Zucc. (Nymphaeaceae). – Aquatic Bot. 23: 83-93.

Carlquist SJ, Schneider EL. 2009a. Distinctive tracheid microstructure in stems of Victoria and Euryale (Nymphaeaceae). – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 159: 52-57.

Carlquist SJ, Schneider EL. 2009b. Do tracheid microstructure and presence of minute crystals link Nymphaeaceae, Cabombaceae and Hydatellaceae? – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 159: 572-582.

Carlquist SJ, Schneider EL, Hellquist CB. 2009. Xylem of early angiosperms: Nuphar (Nymphaeaceae) has novel tracheid microstructure. – Amer. J. Bot. 96: 207-215.

Caspary R. 1891. Nymphaeaceae (Seerosen, Teichrosen, Wasserlilien). – In: Engler A, Prantl K (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien III(2), W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 1-10.

Cevallos-Ferriz SRS, Stockey RA. 1989. Permineralized fruits and seeds from the Princeton Chert (Middle Eocene) of British Columbia: Nymphaeaceae. – Bot. Gaz. 150: 207-217.

Chassat J-F. 1962. Recherches sur la ramification chez les Nymphaeacées. – Bull. Soc. Bot. France, Mém., 1962: 72-95.

Cheeseman TF. 1907. Notice on the occurrence of Hydatella, a new genus to the New Zealand flora. – Trans. New Zealand Inst. 39: 433-434.

Chen I, Manchester SR, Chen Z. 2004. Anatomically-preserved seeds of Nuphar from the early Eocene of Wutu, Shandong Province, China. – Amer. J. Bot. 91: 1265-1272.

Chifflot JBJ. 1902. Contributions à l’étude de la classe des Nymphéinées. – Ann. Univ. Lyon, n. s. I, Sci. Med. 10: 19-38.

Chrysler MA. 1938. The winter buds of Brasenia. – Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 65: 277-283.

Clarke GCS, Jones MR. 1981. Cabombaceae. – Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 33: 51-55.

Coiffard C, Mohr BAR, Bernardes-de-Oliveira MEC. 2013. Jaguariba wiersemana gen. nov. et sp. nov., an Early Cretaceous member of crown group Nymphaeales (Nymphaeaceae) from northern Gondwana. – Taxon 62: 141-151.

Coiro M, Lumaga MRB. 2013. Aperture evolution in Nymphaeacee: insights from a micromorphological and ultrastructural investigation. – Grana 52: 192-201.

Collinson ME. 1980. Recent and Tertiary seeds of the Nymphaeaceae sensu lato with a revision of Brasenia ovula (Brongn.) Reid and Chandler. – Ann. Bot., N. S., 46: 603-632.

Conard HS. 1905. The waterlilies. A monograph of the genus Nymphaea. – Publ. Carnegie Inst. 4: 1-292.

Cook MT. 1902. Development of the embryo sac and embryo of Castalia odorata and Nymphaea advena. – Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 29: 211-220.

Cook MT. 1906. The embryology of some Cuban Nymphaeaceae. – Bot. Gaz. 42: 376-392.

Cooke DA. 1981. New species of Schoenus (Cyperaceae) and Trithuria (Hydatellaceae). – Muelleria 4: 299-303.

Cooke DA. 1983a. Two Western Australian Hydatellaceae. – Muelleria 5: 123-125.

Cooke DA. 1983b. The seedling of Trithuria (Hydatellaceae). – Victorian Natur. 100: 68-69.

Cooke DA. 1987. Hydatellaceae. – In: George AS (ed), Flora of Australia 45, Australian Government Publ. Service, Canberra, pp. 1-5.

Cornejo X, Bonifaz C. 2003. 55A. Nymphaeaceae. – In: Harling G, Andersson L (eds), Flora of Ecuador 70, Botanical Institute, Göteborg University, pp. 3-24.

Cramer JM, Meeuse ADJ, Teunissen P. 1975. A note on the pollination of nocturnally flowering species of Nymphaea. – Acta Bot. Neerl. 24: 489-490.

Cutter EG. 1957. Studies of morphogenesis in the Nymphaeaceae I. Introduction: some aspects of the morphology of Nuphar lutea (L.) Sm. and Nymphaea alba L. – Phytomorphology 7: 45-73.

Cutter EG. 1958. Studies of morphogenesis in the Nymphaeaceae II. Floral development in Nuphar and Nymphaea: bracts and calyx. – Phytomorphology 8: 74-95.

Cutter EG. 1961. The inception and distribution of flowers in the Nymphaeaceae. – Proc. Linn. Soc. London 192: 93-100.

Dacey JWH. 1980. Internal winds in water lilies (Nuphar luteum): an adaptation for life in anaerobic sediments. – Science 210: 1017-1019.

Dacey JWH, Klug MJ. 1979. Methane efflux from lake sediments through water lilies. – Science 203: 1253-1255.

Dkhar J, Kumaria S, Rao S, Tandon P. 2012. Sequence characteristics and phylogenetic implications of the nrDNA internal transcribed spacers (ITS) in the genus Nymphaea with focus on some Indian representatives. – Plant Syst. Evol. 298: 93-108.

Dorofeev PI. 1973.Systematics of ancestral forms of Brasenia. – Paleontol. J. 7: 219-227. [In Russian].

Dorofeev PI. 1984. The taxonomy and history of the genus Brasenia (Cabombaceae). – Bot. Žurn. 69: 137-148. [In Russian]

Duarte JM, Wall KP, Zahn LM, Soltis PS, Soltis DE, Leebens-Mack J, Carlson JE, Ma HW, dePamphilis CW. 2008. Utility of Amborella trichopoda and Nuphar advena expressed sequence tags for comparative sequence analysis. – Taxon 57: 1110-1122.

Edgar E. 1966. The male flowers of Hydatella inconspicua (Cheesem.) Cheesem. (Centrolepidaceae). – New Zealand J. Bot. 4: 153-158.

Edgar E. 1970. Centrolepidaceae. – In: Moore LB, Edgar E (eds), Flora of New Zealand 2, Wellington.

Endress PK. 2005. Carpels in Brasenia (Cabombaceae) are completely ascidiate despite a long stigmatic crest. – Ann. Bot. 96: 209-215.

Ervik F, Knudsen JT. 2003. Water lilies and scarabs: faithful partners for 100 million years? – Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 80: 539-543.

Ervik F, Renner SS, Johansson KA. 1995. Breeding system and pollination of Nuphar luteum (L.) Sith (Nymphaeaceae) in Norway. – Flora 190: 109-113.

Fassett NC. 1953. A monograph on the genus Cabomba. – Castanea 13: 116-128.

Floyd SK, Friedman WE. 2001. Developmental evolution of endosperm in basal angiosperms: evidence from Amborella (Amborellaceae), Nuphar (Nymphaeaceae), and Illicium (Illiciaceae). – Plant Syst. Evol. 228: 153-169.

Fossen T, Andersen OM. 1999. Delphinidin 3-galloyl-galactosids from blue flowers of Nymphaea caerulea. – Phytochemistry 50: 1185-1188.

Fossen T, Larsen A, Andersen OM. 1998. Anthocyanins from flowers and leaves of Nymphaea x marliacea cultivars. – Phytochemistry 48: 823-827.

Friedman WE. 2008. Hydatellaceae are water lilies with gymnospermous tendencies. – Nature 453: 94-97.

Friedman WE, Bachelier JB, Hormaza JI. 2012. Embryology in Trithuria submersa (Hydatellaceae) and relationships between embryo, endosperm, and perisperm in early-diverging flowering plants. – Amer. J. Bot. 99: 1083-1095.

Friis EM, Pedersen KR, Crane PR. 2001. Fossil evidence of water lilies (Nymphaeales) in the Early Cretaceous. – Nature 410: 357-360.

Friies EM, Pedersen KR, Balthazar M von, Grimm GW, Crane PR. 2009. Monetianthus mirus gen. et sp. nov., a nymphaealean flower from the Early Cretaceous of Portugal. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 170: 1086-1101.

Gabarayeva NI, El-Ghazaly G. 1997. Sporoderm development in Nymphaea mexicana (Nymphaeaceae). – Plant Syst. Evol. 204: 1-19.

Gabarayeva NI, Rowley JR. 1994. Exine development of Nymphaea colorata (Nymphaeaceae). – Nord. J. Bot. 14: 671-691.

Gabarayeva NI, Walles B, El-Ghazaly G, Rowley JR. 2001. Exine and tapetum development in Nymphaea capensis (Nymphaeaceae): a comparative study. – Nord. J. Bot. 21: 529-548.

Gabarayeva NI, Grigoryeva VV, Rowley JR. 2003. Sporoderm ontogeny in Cabomba aquatica (Cabombaceae). – Rev. Paleobot. Palynol. 127: 147-173.

Galati BG. 1981. The ontogeny of hairs and stomata of Cabomba australis (Nymphaeaceae). – Lilloa 35: 149-158.

Galati BG. 1985. Estudios embriológicos en Cabomba australis I. La esporogénesis y las generaciones sexuadas. – Bol. Soc. Argent. Bot. 24: 29-47.

Galati BG. 1987. Estudios embriológicos en Cabomba australis (Nymphaeaceae) II. Ontogenía de la semilla. – Bol. Soc. Argent. Bot. 25: 187-196.

Gandolfo MA, Nixon KC, Crepet WL. 2004. Cretaceous flowers of Nymphaeaceae and implications for complex insect entrapment pollination mechanisms in early angiosperms. – Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101: 8056-8060.

Gessner F. 1969. Zur Blattentwicklung von Victoria amazonica (Popp.) Sowerby. – Ber. Deutsch. Bot. Ges. 82: 603-608.

Giesen TG, Velde G van der. 1983. Ultraviolet reflectance and absorption patterns in flowers of Nymphaea alba L., Nymphaea candida Presl and Nuphar lutea (L.) Sm. (Nymphaeaceae). – Aquatic Bot. 16: 369-376.

Gilg-Benedict C. 1930. Centrolepidaceae. – In: Engler A (ed), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien, 2. Aufl., Bd. 15a, W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 27-33.

Goleniewska-Furmanowa M. 1970. Comparative leaf anatomy and alkaloid content in the Nymphaeaceae. – Monogr. Bot. 31: 5-54.

Goremykin VM, Hirsch-Ernst KI, Wölfl S, Hellwig FH. 2004. The chloroplast genome of Nymphaea alba: whole-genome analyses and the problem of identifying the most basal angiosperm. – Mol. Biol. Evol. 21: 1445-1454.

Graham SW, Olmstead RG. 2000. Evolutionary significance of an unusual chloroplast DNA inversion found in two basal angiosperm lineages. – Curr. Genet. 37: 183-188.

Grob V, Moline P, Pfeifer E, Novelo AR, Rutishauser R. 2006. Developmental morphology of branching flowers in Nymphaea prolifera. – J. Plant Res. 119: 561-570.

Gruenstaeudl M, Nauheimer L, Borsch T. 2017. Plastid genome structure and phylogenomics of Nymphaeales: conserved gene order and new insights into relationships. – Plant Syst. Evol. 303: 1251-1270.

Grüss J. 1927. Die Luftblätter der Nymphaeaceen. – Ber. Deutsch. Bot. Ges. 45: 454-458.

Gupta PP. 1978. Cytogenetics of aquatic ornamentals II. Cytology of Nymphaeas. – Cytologia 43: 477-484.

Gupta PP. 1980. Cytogenetics of aquatic ornamentals VI. Evolutionary trends and relationships in the genus Nymphaea. – Cytologia 45: 307-314.

Guttenberg HV, Müller-Schroeder R. 1958. Untersuchungen über die Entwicklung des Embryos und der Keimpflanze von Nuphar luteum. – Planta 51: 481-510.

Gwynne-Vaughan DT. 1897. On some points on the morphology and anatomy of the Nymphaeaceae. – Trans. Linn. Soc. London, ser. II, Botany 5: 287-299.

Haines RW, Lye KA. 1975. Seedlings of Nymphaeaceae. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 70: 255-265.

Hamann U. 1975. Neue Untersuchungen zur Embryologie und Systematik der Centrolepidaceen. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 96: 154-191.

Hamann U. 1976. Hydatellaceae – a new family of Monocotyledoneae. – New Zealand J. Bot. 14: 193-196.

Hamann U. 1998. Hydatellaceae. – In: Kubitzki K (ed), The families and genera of vascular plants IV. Flowering plants. Monocotyledons. Alismatanae and Commelinanae (except Gramineae), Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 231-234.

Hamann U, Kaplan K, Rübsamen T. 1979. Über die Samenschalenstruktur der Hydatellaceae (Monocotyledoneae) und die systematische Stellung von Hydatella filamentosa. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 100: 555-563.

Harada I. 1979. Diaphragm development in root aerenchyma of Victoria cruziana. – J. Fac. Sci. Hokkaido Univ., Ser. V, Botany 11: 274-278.

Hart KH, Cox PA. 1995. Dispersal ecology of Nuphar luteum (L.) Sibthorp & Smith: abiotic seed dispersal mechanisms. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 119: 87-100.

Hartog C den. 1970. Ondinea – a new genus of Nymphaeaceae. – Blumea 18: 413-416.

Heel WA van. 1977. The pattern of vascular bundles in the stamens of Nymphaea lotus L. and its bearing on the stamen morphology. – Blumea 23: 345-348.

Heine H. 1958. Barclaya longifolia Wallich, eine neueingeführte wertvolle Aquarienpflanze. – Aquar. Terrar.-Zeitschr. 11: 314-317; 345-346.

Heinsbroek PG, Heel WA van. 1969. Note on the bearing of the pattern of vascular bundles on the morphology of the stamens of Victoria amazonica (Poep.) Sowerby. – Kon. Nederl. Akad. Wet. Proc., ser. C, 72: 431-444.

Henkel F, Rehnelt F, Dittmann L. 1907. Das Buch der Nymphaeaceen oder Seerosengewächse. – F. Henkel, Darmstadt.

Heslop-Harrison Y. 1955. Nuphar Sm. – J. Ecol. 43: 342-364.

Hirthe G, Porembski S. 2003. Pollination of Nymphaea lotus (Nymphaeaceae) by rhinoceros beetles and bees in the northeastern Ivory Coast. – Plant Biol. 5: 670-675.

Hotta M. 1966. Notes on Bornean plants I. – Acta Phytotaxon. Geobot. 22: 9-10.

Hu S-Y. 1968. The genus Barclaya (Nymphaeaceae). – In: Studies in the flora of Thailand 48, Dansk Bot. Ark. 23: 534-541.

Iles WJD, Rudall PJ, Sokoloff DD. Remizowa MV, Macfarlane TD, Logacheva MD, Graham SW. 2012. Molecular phylogenetics of Hydatellaceae (Nymphaeales): sexual-system homoplasy and a new sectional classification. – Amer. J. Bot. 99: 663-676.

Iles WJD, Lee C, Sokoloff DD, Remizowa MV,

Yadav SR, Barrett MD, Barrett RL, Macfarlane TD, Rudall PJ, Graham SW. 2014.

Reconstructing the age and historical biogeography of the ancient

flowering-plant family Hydatellaceae (Nymphaeales). – BMC Evol. Biol. 14:

1-23.

Inambar JA, Aleykutty KM. 1979. Studies on Cabomba aquatica (Cabombaceae). – Plant Syst. Evol. 132: 161-166.

Ishimatsu M, Tanaka T, Nonaka G, Nishioka I, Nishizawa M, Yamagishi T. 1989. Tannins and related compounds LXXIX. Isolation and characterisation of novel dimeric and trimeric hydrolysable tannins, nuphrins C, D, E and F, from Nuphar japonicum DC. – Chem. Pharmac. Bull. 37: 1735-1743.

Ito M. 1982. On the embryos and the seedlings of the Nymphaeaceae. – Acta Phytotaxon. Geobot. 33: 143-148.

Ito M. 1983. Studies in the floral morphology and anatomy of Nymphaeales I. The morphology of vascular bundles in the flower of Nymphaea tetragona George. – Acta Phytotaxon. Geobot. 34: 18-26.

Ito M. 1984. Studies in the floral morphology and anatomy of Nymphaeales II. The floral anatomy of Nymphaea tetragona George. – Acta Phytotaxon. Geobot. 35: 94-102.

Ito M. 1986a. Studies in the floral morphology and anatomy of Nymphaeales III. Floral anatomy of Brasenia schreberi Gmel. and Cabomba caroliniana A. Gray. – Bot. Mag. (Tokyo) 99: 169-184.

Ito M. 1987. Phylogenetic systematics of the Nymphaeales. – Bot. Mag. (Tokyo) 100: 17-35.

Jacobs SWL. 1992. New species, lectotypes and synonyms of Australasian Nymphaea (Nymphaeaceae). – Telopea 4: 635-641.

Jacobs SWL. 1994. Further notes on Nymphaea (Nymphaeaceae) in Australasia. – Telopea 5: 703-706.

Jacobs SWL, Hellquist CB. 2006. Three new species of Nymphaea (Nymphaeaceae) in Australia. – Telopea 11: 155-160.

Kaden NN. 1951. Fruits and seeds of Middle Russian Nymphaeaceae and Berberidaceae. – Bull. Moscow Soc. Natur., Biol. Ser. 56: 81-90.

Kadono Y, Schneider EL. 1987. The life history of Euryale ferox Salisb. in southwestern Japan with special reference to reproductive ecology. – Plant Species Biol. 2: 109-115.

Kakuta M, Misaki A. 1979. The polysaccharide of Junsai (Brasenia schreberi) mucilage: fragmentation analysis by successive Smith degradations and partial acid hydrolysis. – Agric. Biol. Chem. 43: 1269-1276.

Kenneally KF, Schneider EL. 1983. On the genus Ondinea (Nymphaeaceae) including a new subspecies from the Kimberley region, Western Australia. – Nuytsia 4: 359-365.

Khanna P. 1964. Morphological and embryological studies in Nymphaeaceae I. Euryale ferox. – Proc. Indian Acad. Sci., Sect. B, 59: 237-243.

Khanna P. 1965. Morphological and embryological studies in Nymphaeaceae II. Brasenia Schreberi Gmel. and Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. – Aust. J. Bot. 13: 379-387.

Khanna P. 1967. Morphological and embryological studies in Nymphaeaceae III. Victoria cruziana d’Orb. und Nymphaea stellata Willd. – Bot. Mag. (Tokyo) 80: 305-312.

King J. 1889. Barclaya motleyi var. kunstleri. – As. Soc. Bengal 58: 390.

Knoch E. 1899. Untersuchungen über die Morphologie, Biologie und Physiologie der Blüte von Victoria regia. – Bibl. Bot. 9: 1-67.

Kosakai H. 1968. The comparative xylary anatomy of various Nymphaeaceae. – M.A. diss., University of California, Santa Barbara, California.

Kristen U. 1974. Zur Feinstruktur der submersen Drüsenpapillen von Brasenia schreberi und Cabomba caroliniana. – Cytobiologie 9: 36-44.

Landon K, Edwards RA, Nozaic PI. 2006. A new species of waterlily (Nymphaea minuta: Nymphaeaceae) from Madagascar. – Sida 22: 887-893.

Langlet O. 1936. Några bidrag till kännedomen om kromosomtalen inom Nymphaeaceae, Ranunculaceae, Polemoniaceae, och Compositae. – Svensk Bot. Tidskr. 30: 288-294.

Langlet O, Söderberg E. 1929. Über die Chromosomenzahlen einiger Nymphaeaceen. – Acta Horti Berg. 9: 85-104.

La-ongsri W, Trisonthi C, Balslev H. 2009. A synopsis of Thai Nymphaeaceae. – Nord. J. Bot. 27: 97-114.

Les DH, Garvin DK, Wimpee CF. 1991. Molecular evolutionary history of ancient aquatic angiosperms. – Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88: 10119-10123.

Les DH, Schneider EL, Padgett DJ, Soltis PS, Soltis DE, Zanis M. 1999. Phylogeny, classification and floral evolution of water lilies (Nymphaeaceae; Nymphaeales): a synthesis of non-molecular, rbcL, matK, and 18S rDNA data. – Syst. Bot. 24: 28-46.

Li H-L. 1955. Classification and phylogeny of Nymphaeaceae and allied families. – Amer. Midl. Natur. 54: 33-41.

Liu Y-L, Xu L-M, Ni X-M, Zhao J-R. 2005. Phylogeny of the Nymphaeaceae inferred from ITS sequences. – Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 43: 22-30.

Löhne C. 2006. Molecular phylogenetics and historical biogeography of basal angiosperms: a case study in Nymphaeales. – Ph.D. diss., Universität Bonn, Bonn, Germany.

Löhne C, Borsch T, Wiersema JH. 2007. Phylogenetic analysis of Nymphaeales using fast-evolving and noncoding chloroplast markers. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 154: 141-163.

Löhne C, Yoo M-J, Borsch T, Wiersema J, Wilde V, Bell CD, Barthlott W, Soltis DE, Soltis PS. 2008. Biogeography of Nymphaeales: extant patterns and historical events. – Taxon 57: 1123-1146.

Löhne C, Borsch T, Jacobs SWL, Hellquist CB, Wiersema JH. 2008. Nuclear and plastid DNA sequences reveal complex reticulate patterns in Australian water-lilies (Nymphaea subgenus Anecphya, Nymphaeaceae). – Aust. Syst. Bot. 21: 229-250.

Löhne C, Wiersema JH, Borsch T. 2009. The unusual Ondinea, actually just another Australian water-lily of Nymphaea subg. Anecphya (Nymphaeaceae). – Willdenowia 38: 55-58.

Lovejoy TE. 1978. Royal water lilies, truly Amazonian. – Smithsonian 9: 78-84.

Lüttge U, Krapf G. 1969. Die Ultrastruktur der Nymphaea-Hydropoten in Zusammenhang mit ihrer Funktion als Salztransportierende Drüsen. – Cytobiologia 1: 121-431.

Mackenzie LT, Hudson PJ, Rigg JM, Strandquist JN, Green JS, Thiemann TC, Osborn JM. 2013. Pollen ontogeny in Victoria (Nymphaeles). – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 174: 1259-1276.

Mackenzie LT, Cooper RL, Schneider EL, Osborn JM. 2015. Pollen structure and development in Nymphaeales: insights into character evolution in an ancient angiosperm lineage. – Amer. J. Bot. 102: 1685-1702.

Malaviya M. 1962. A study of sclereids in three species of Nymphaea. – Proc. Indian Acad. Sci., Sect. B, 56: 232-236.

Meeuse BJD, Schneider EL. 1980. Nymphaea revisited: a preliminary communication. – Israel J. Bot. 28: 65-79.

Mendonça FA. 1960. 10. Nymphaeaceae. – In: Exell AW, Wild H (eds), Flora Zambesiaca 1 (Part 1), Crown Agents for Oversea Governments and Administrations, London, pp. 175-180.

Meyer NR. 1964. Palynological studies of the family Nymphaeaceae. – Bot. Žurn. 49: 1421-1429. [In Russian]

Miegroet F van, Dujardin M. 1992. Cytologie et histologie de la reproduction chez le Nymphaea heudelottii. – Can. J. Bot. 70: 1991-1996.

Mohr BAR, Bernardes-de-Oliveira MEC, Taylor DW. 2008. Pluricarpellatia, a nymphaealean angiosperm from the Lower Cretaceous of northern Gondwana (Crato Formation, Brazil). – Taxon 57: 1147-1158.

Moseley MF. 1958. Morphological studies of the Nymphaeaceae: I. The nature of the stamens. – Phytomorphology 8: 1-29.

Moseley MF. 1961. Morphological studies of the Nymphaeaceae II. The flower of Nymphaea. – Bot. Gaz. 122: 233-259.

Moseley MF. 1965. Morphological studies of the Nymphaeaceae III. The floral anatomy of Nuphar. – Phytomorphology 15: 54-84.

Moseley MF. 1971. Morphological studies of the Nymphaeaceae VI. Development of the flower of Nuphar. – Phytomorphology 21: 253-283.

Moseley MF. 1986. Examples of vascular anatomical differences in the peduncles and flowers among “nymphaeaceous” taxa. – Amer. J. Bot. 73: 776.

Moseley MF, Williamson PS. 1984. The vasculature of the flower of Euryale Ferox. – Amer. J. Bot. 71: 40-41.

Moseley MF, Mehta IJ, Williamson PS, Kosakai H. 1984. Morphological studies of the Nymphaeaceae (sensu lato) XIII. Contributions to the vegetative and floral structure of Cabomba. – Amer. J. Bot. 71: 902-924.

Moseley MF, Schneider EL, Williamson PS. 1993. Phylogenetic interpretations from selected floral vasculature characters in the Nymphaeaceae sensu lato. – Aquatic Bot. 44: 325-342.

Muller J. 1970. Description of pollen grains of Ondinea purpurea den Hartog. – Blumea 18: 416-417.

Nitzschke J. 1914. Beiträge zur Phylogenie der Monokotylen, gegründet auf die Embryosackentwicklung apokarper Nymphaeaceen und Helobien. – Cohns Beitr. Biol. Pflanzen 12: 223-267.

Nixon KC. 2008. Paleobotany, evidence, and molecular dating: an example from the Nymphaeales. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 95: 43-50.

Okada H, Tamura M. 1981. Karyomorphological study on the Nymphaeales. – J. Jap. Bot. 56: 367-374.

Okada Y. 1930. Study of Euryale ferox Salisb. VI. Cleistogamous versus chasmogamous flower. – Bot. Mag. (Tokyo) 44: 369-373.

Okada Y. 1938. On chasmogamous flowers of Euryale ferox Salisb. – Ecol. Rev. 4: 159-163. [In Japanese]

Orban I, Bouharmont J. 1995. Reproductive biology of Nymphaea capensis Thunb. var. zanzibariensis (Casp) Verdc. (Nymphaeaceae). – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 119: 35-43.

Orban I, Bouharmont J. 1998. Megagametophyte development of Nymphaea nouchali Burm. f. (Nymphaeaceae). – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 126: 339-348.

Ørgaard M. 1991. The genus Cabomba (Cabombaceae) – a taxonomic study. – Nord. J. Bot. 11: 179-203.

Osborn JM, Schneider EL. 1988. Morphological studies of the Nymphaeaceae sensu lato XVI. The floral biology of Brasenia schreberi. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 75: 778-794.

Osborn JM, Taylor TN, Schneider SL. 1991. Pollen morphology and ultrastructure of the Cabombaceae: correlations with pollination biology. – Amer. J. Bot. 78: 1367-1378.

Paclt J. 1998. Proposal to amend the gender of Nuphar, nom. cons. (Nymphaeaceae), to neuter. – Taxon 47: 167-169.

Padgett DJ. 1997. A biosystematic monograph of the genus Nuphar Sm. (Nymphaeaceae). – Ph.D. diss., University of New Hampshire, Durham, New Hampshire.

Padgett DJ. 2007. A monograph of Nuphar (Nymphaeaceae). – Rhodora 109: 1-95.

Padgett DJ, Les DH, Crow GE. 1999. Phylogenetic relationships in Nuphar (Nymphaeaceae): evidence from morphology, chloroplast DNA, and nuclear ribosomal DNA. – Amer. J. Bot. 86: 1316-1324.

Padmanabhan D. 1970. Comparative embryology of angiosperms: Nymphaeaceae. – Bull. Natl. Sci. Acad. India 41: 59-62.

Padmanabhan D, Ramji MY. 1966. Developmental studies on Cabomba caroliniana Gray II. Floral anatomy and microsporogenesis. – Proc. Indian Acad. Sci., Sect. B, 64: 216-223.

Paffrath K. 1972. Nochmals Barclaya longifolia. – Aquar. Terrar.-Zeitschr. 25: 372-374.

Pledge DH. 1974. Some observations on Hydatella inconspicua (Cheesem.) Cheesem. (Centrolepidaceae). – New Zealand J. Bot. 12: 559-561.

Prance GT. 1980. A note on the pollination of Nymphaea amazonum Mart. and Zucc. (Nymphaeaceae). – Brittonia 32: 505-507.

Prance GT, Anderson AB. 1976. Studies on the floral biology of neotropical Nymphaeaceae 3. – Acta Amazonica 6: 163-170.

Prance GT, Arias JR. 1975. A study of the floral biology of Victoria amazonica (Poepp.) Sowerby (Nymphaeaceae). – Acta Amazonica 5: 109-139.

Protopapas A. 2001. The re-discovery of Nymphaea micrantha. – Water Gard. J. 2001: 18-22.

Prychid CJ, Sokoloff DD, Remizowa MV, Tuckett RE, Yadav SR, Rudall PJ. 2011. Unique stigmatic hairs and pollen-tube growth within the stigmatic cell wall in the early-divergent angiosperm family Hydatellaceae. – Ann. Bot. 108: 599-608.

Raciborski M. 1894. Die Morphologie der Cabombeen und Nymphaeaceen. – Flora 78: 244-279.

Ramji MY, Padmanabhan D. 1965. Developmental studies on Cabomba caroliniana Gray I. Ovule and carpel. – Proc. Indian Acad. Sci., Sect. B, 62: 215-223.

Remizowa MV, Sokoloff DD, Macfarlane TD, Yadav SR, Prychid CJ, Rudall PJ. 2008. Comparative pollen morphology in the early-divergent angiosperm family Hydatellaceae reveals variation at the infraspecific level. – Grana 47: 81-100.

Rao TA, Banerjee BC. 1979. On foliar sclereids in the Nymphaeaceae sensu lato and their use in familial classification. – Proc. Indian Acad. Sci., Sect. B, 88: 413-422.

Rataj K. 1977. A new species of Cabomba of the Negro river, Amazonas, Brazil. – Acta Amazonica 7: 143.

Rataj K. 1979. Le genre Cabomba. – Aquarama 13: 21-24.

Raubeson LA, Peery R, Chumley TW, Dziubek C, Fourcade HM, Boore JL, Jansen RK. 2007. Comparative chloroplast genomics: analyses including new sequences from the angiosperms Nuphar advena and Ranunculus macranthus. – BMC Genomics 8: 174.

Raymond M, Dansereau P. 1953. The geographic distribution of the bipolar Nymphaeaceae, Nymphaea tetragona and Brasenia schreberi. – Proc. 7th Pacific Sci. Congr. 7(5): 122-131.

Remizowa M, Sokoloff D, Macfarlane T, Yadav S, Prychid C, Rudall P. 2008. Comparative pollen morphology in the early-divergent angiosperm family Hydatellaceae reveals variation at the infraspecific level. – Grana 47: 81-100.

Ren D. 1998. Flower-associated Brachycera flies as fossil evidence for Jurassic angiosperm origins. – Science 280: 85-88.

Richardson FC. 1969. Morphological studies of the Nymphaeaceae IV. Structure and development of the flower of Brasenia schreberi Gmel. – Univ. Calif. Publ. Bot. 47: 1-101.

Richardson FC, Moseley M. 1967. The vegetative morphology and nodal structure of Brasenia schreberi. – Amer. J. Bot. 54: 645.

Riemer DN, Ilnicki RD. 1968. Reproduction and overwintering of Cabomba in New Jersey. – Weed Science 16: 101-102.

Riemer DN, Toth SJ. 1970. Chemical composition of five species of Nymphaeaceae. – Weed Science 18: 4-6.

Rowley JR, Gabarayeva NI, Walles B. 1992. Cyclic invasion of tapetal cells into loculi during microspore development in Nymphaea colorata (Nymphaeaceae). – Amer. J. Bot. 79: 801-808.

Royen P van. 1962. Sertulum Papuanum 5. Nymphaeaceae. – Nova Guinea, Bot. 8: 103-126.

Rudall PJ, Sokoloff DD, Remizowa MV, Conran JG, Davis JI, Macfarlane TD, Stevenson DW. 2007. Morphology of Hydatellaceae, an anomalous aquatic family recently recognized as an early-divergent angiosperm lineage. – Amer. J. Bot. 94: 1073-1092.

Rudall PJ, Remizowa MV, Beer AS, Bradshaw E, Stevenson DW, Macfarlane TD, Tuckett RE, Yadav SR, Sokoloff DD. 2008. Comparative ovule and megagametophyte development in Hydatellaceae and water lilies reveal a mosaic of features among the earliest angiosperms. – Ann. Bot. 101: 941-956.

Rudall PJ, Remizowa MV, Prenner G, Prychid CJ, Tuckett RE. Sokoloff DD. 2009. Nonflowers near the base of extant angiosperms? Spatiotemporal arrangement of organs in reproductive units of Hydatellaceae and its bearing on the origin of the flowers. – Amer. J. Bot. 96: 67-82.

Saarela JM, Rai HS, Doyle JA, Endress PK, Mathews S, Marchant AD, Briggs B, Graham SW. 2007. Hydatellaceae identified as a new branch near the base of the angiosperm phylogenetic tree. – Nature 446: 312-315.

Schaffner JH. 1904. Some morphological peculiarities of the Nymphaeaceae and Helobiae. – Ohio Naturalist 4: 83-92.

Schmucker T. 1932. Physiologische und ökologische Untersuchungen an Blüten tropischer Nymphaea-Arten. – Planta 16: 376-412.

Schmucker T. 1933. Zur Blütenbiologie tropischer Nymphaea-Arten II. Bor als entscheidender Faktor. – Planta 18: 641-650.

Schneider EL. 1976. Morphological studies of the Nymphaeaceae VIII. The floral anatomy of Victoria Schomb. (Nymphaeaceae). – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 72: 115-148.

Schneider EL. 1978a. Morphological studies of the Nymphaeaceae IX. The seed of Barclaya longifolia Wall. – Bot. Gaz. 139: 223-230.

Schneider EL. 1978b. Morphological studies of the Nymphaeaceae X. The seed of Ondinea purpurea den Hartog. – Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 105: 192-200.

Schneider EL. 1979. Pollination biology of the Nymphaeaceae. – Proceedings of the 4th international symposium on pollination, Maryland Agric. Exp. Sta. Spec. Misc. Publ. 1: 419-430.

Schneider EL. 1982a. Notes on the floral biology of Nymphaea elegans (Nymphaeaceae) in Texas. – Aquatic Bot. 12: 197-200.

Schneider EL. 1982b. Observations on the pollination biology of Nymphaea gigantea W. J. Hooker (Nymphaeaceae). – West. Aust. Natur. 15: 71-72.

Schneider EL. 1983. Gross morphology and floral biology of Ondinea purpurea den Hartog. – Aust. J. Bot. 31: 371-382.

Schneider EL, Carlquist SJ. 1995a. Vessels in the roots of Barclaya rotundifolia (Nymphaeaceae). – Amer. J. Bot. 82: 1343-1349.

Schneider EL, Carlquist SJ. 1995b. Vessel origins in Nymphaeaceae: Euryale and Victoria. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 119: 185-193.

Schneider EL, Carlquist SJ. 1996a. Vessel origin in Cabomba. – Nord. J. Bot. 16: 637-641.

Schneider EL, Carlquist SJ. 1996b. Vessels in Brasenia (Cambombaceae): new perspectives on vessel origin in primary xylem of angiosperms. – Amer. J. Bot. 83: 1236-1240.

Schneider EL, Carlquist SJ. 2009. Xylem of early angiosperms: novel microstructure in stem tracheids of Barclaya (Nymphaeaceae). – Aquatic Bot. 91: 61-66.

Schneider EL, Chaney T. 1981. The floral biology of Nymphaea odorata (Nymphaeaceae). – Southwest. Natur. 26: 159-165.

Schneider EL, Ford EG. 1978. Morphological studies of the Nymphaeaceae X. The seed of Ondinea purpurea Den Hartog. – Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 105: 192-200.

Schneider EL, Jeter JM. 1982. Morphological studies of the Nymphaeaceae XII. The floral biology of Cabomba caroliniana. – Amer. J. Bot. 69: 1410-1419.

Schneider EL, Moore LA. 1977. Morphological studies of the Nymphaeaceae VII. The floral biology of Nuphar lutea subsp. macrophylla. – Brittonia 29: 88-99.

Schneider EL, Williamson PS. 1993. Nymphaeaceae. – In: Kubitzki K, Rohwer JG, Bittrich V (eds), The families and genera of vascular plants II. Flowering plants. Dicotyledons. Magnoliid, hamamelid and caryophyllid families, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 486-493.

Schneider EL, Moseley MF, Williamson PS. 1984. The pollination biology of Ondinea purpurea (Nymphaeaceae). – In: Proceedings of th 5th international symposium on pollination, INRA Publ. (Les Colloques de l’INRA, n-21), pp. 231-235.

Schneider EL, Carlquist SJ, Beamer K, Kohn K. 1995. Vessels in Nymphaeaceae: Nuphar, Nymphaea, and Ondinea. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 156: 857-862.

Schneider EL, Tucker SC, Williamson PS. 2003. Floral development in the Nymphaeales. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 164(Suppl.): S279-S292.

Schneider EL, Carlquist SJ, Hellquist CB. 2009. Microstructure of tracheids of Nymphaea. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 170: 457-466.

Schrenk J. 1888. On the histology of the vegetative organs of Brasenia peltata, Pursh. – Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 15: 29-49.

Seago JL Jr. 2002. The root cortex of Nymphaeaceae, Cabombaceae and Nelumbonaceae. – J. Torrey Bot. Soc. 129: 1-9.

Seymour RS, Matthews PGD. 2006. The role of thermogenesis in the pollination biology of the Amazon waterlily Victoria amazonica. – Ann. Bot. 98: 1129-1135.

Shamrov II. 1998. Formation of hypostase, podium and postament in the ovule of Nuphar lutea (Nymphaeaceae) and Ribes aureum (Grossulariaceae). – Bot. Žurn. 83: 3-14. [In Russian]

Simon J-P. 1971. Comparative serology of the order Nymphaeales II. Relationships of Nymphaeaceae and Nelumbonaceae. – Aliso 7: 325-350.

Skubatz H, Williamson PS, Schneider EL, Meeuse BJD. 1990. Cyanide-insensitive respiration in thermogenic flowers of Victoria and Nelumbo. – J. Exp. Bot. 41(231): 1335-1339.

Snigiryevskaya NS. 1955. Pollen morphology in Nymphaeales. – Bot. Žurn. 40: 108-115. [In Russian]

Sokoloff DD, Remizowa MV, Macfarlane TD, Tuckett RE, Ramsay MM, Beer AS, Yadav SR, Rudall PJ. 2008. Seedling diversity in Hydatellaceae: implications for the evolution of angiosperm cotyledons. – Ann. Bot. 101: 153-164.

Sokoloff DD, Remizowa MV, Macfarlane TD, Rudall PJ. 2008. Classification of the early-divergent angiosperm family Hydatellaceae: one genus instead of two, four new species and sexual dimorphism in dioecious taxa. – Taxon 57: 179-200.

Sokoloff DD, Remizowa MV, Yadav SR, Rudall PJ. 2010. Development of reproductive structures in the sole Indian species of Hydatellaceae , Trithuria konkanensis, and its morphological differences from Australian taxa. – Aust. Syst. Bot. 23: 217-228.

Sokoloff DD, Remizowa MV, Macfarlane TD, Conran JG, Yadav SR, Rudall PJ. 2013. Comparative fruit structure in Hydatellaceae (Nymphaeales) reveals specialized pericarp dehiscence in some early-divergent angiosperms with ascidiate carpels. – Taxon 62: 40-61.

Sokoloff DD, Remizowa MV, Beer AS, Yadav SR, Macfarlane TD, Ramsay MM, Rudall PJ. 2013. Impact of spatial constraints during seed germination on the evolution of angiosperm cotyledons: a case study from tropical Hydatellaceae (Nymphaeales). – Amer. J. Bot. 100: 824-843.

Sokoloff DD, Remizowa MV, Conran JG,

Macfarlane TD, Ramsay MM, Rudall PJ. 2014. Embryo and seedling morphology in

Trithuria lanterna (Hydatellaceae, Nymphaeales): new data for

infrafamilial systematics and a novel type of syncotyly. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc.

174: 551-573.

Stone BC. 1979. Barclaya, the Malaysian “waterlily”. – Malayan Nat. J., Sept.: 20-22.

Stone BC. 1982. A new combination for Barclaya kunstleri (King) Ridley of the Nymphaeaceae. – Gard. Bull. (Singapore) 35: 69-71.

Swindells P. 1983. Waterlilies. – Timber Press, Portland, Oregon.

Takahashi M. 1992. Development of spinous exine in Nuphar japonicum De Candolle (Nymphaeaceae). – Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 75: 317-322.

Takahashi M, Crane PR, Friis EM. 2007. Fossil seeds of Nymphaeales from the Tamayama Formation (Futaba Group), Upper Cretaceous (Early Santonian) of northeastern Honshu, Japan. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 168: 341-350.

Tamura M. 1982. Relationship of Barclaya and classification of Nymphaeales. – Acta Phytotaxon. Geobot. 33: 336-345. [In Japanese]

Tannert R. 1949. Unsere schönen Cabomba-Arten. – Wochenschrift für Aquarien- und Terrarienkunde 42-43: 352-354.

Taylor DW. 2008. Phylogenetic analysis of Cabombaceae and Nymphaeaceae based on vegetative and leaf architectural characters. – Taxon 57: 1082-1095.

Taylor DW, DeVore ML, Pigg KB. 2006. Susiea newsalemae gen. et sp. nov. (Nymphaeaceae): Euryale-like seeds from the Late Paleocene Almont Flora, North Dakota, USA. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 167: 1271-1278.

Taylor DW, Brenner GJ, Basha SH. 2008. Scutifolium jordanicum gen. et sp. nov. (Cabombaceae), an aquatic fossil plant from the Lower Cretaceous of Jordan, and the relationships of related leaf fossils to living genera. – Amer. J. Bot. 95: 340-352.

Taylor ML, Osborn JM. 2006. Pollen ontogeny in Brasenia (Cabombaceae, Nymphaeales). – Amer. J. Bot. 93: 344-356.

Taylor ML, Williams JH. 2009. Consequences of pollination syndrome evolution for postpollination biology in an ancient angiosperm family. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 170: 584-598.

Taylor ML, Gutman BL, Melrose NA, Ingraham AM, Schwartz JA, Osborn JM. 2008. Pollen and anther ontogeny in Cabomba caroliniana (Cabombaceae, Nymphaeales). – Amer. J. Bot. 95: 399-413.

Taylor ML, Hudson PJ, Rigg JM, Strandquist JN, Green JS, Thiemann TC, Osborn JM. 2012. Tapetum structure and ontogeny in Victoria (Nymphaeaceae). – Grana 51: 107-118.

Teixeira C. 1945. Nymphéacées fossiles du Portugal. – Serviços Geológicos de Portugal, Lisbon.

Tillich H-J. 1990. Die Keimpflanzen der Nymphaeaceae – monocotyl oder dicotyl? – Flora 184: 169-176.

Tillich H-J, Tuckett R, Facher E. 2007. Do Hydatellaceae belong to the monocotyledons or basal angiosperms? Evidence from seedling morphology. – Willdenowia 37: 399-406.

Tratt J, Prychid CJ, Behnke H-D, Rudall PJ. 2009. Starch accumulating (S-type) sieve-element plastids in Hydatellaceae: implications for plastid evolution in flowering plants. – Protoplasma 237: 19-26.

Troll W. 1933. Beiträge zur Morphologie des Gynaeceums IV. Über das Gynaeceum der Nymphaeaceen. – Planta 21: 447-485.

Tucker SC, Douglas AW. 1996. Floral structure, development, and relationships of paleoherbs: Saruma, Cabomba, Lactoris, and selected Piperales. – In: Taylor DW, Hickey LJ (eds), Flowering plant origin, evolution and phylogeny, Chapman and Hall, New York, pp. 141-175.

Tuckett RE, Merritt DJ, Rudall PJ, Hay F, Hopper SD, Baskin CC, Basin JM, Tratt J, Dixon KW. 2010. A new type of specialized morphophysiological dormancy and seed storage behaviour in Hydatellaceae, an early-divergent angiosperm family. – Ann. Bot. 105: 1053-1061.