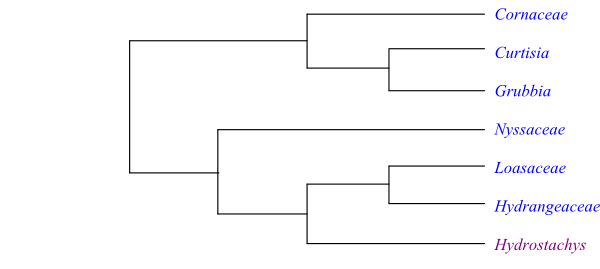

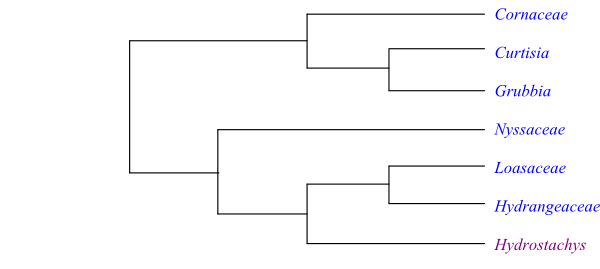

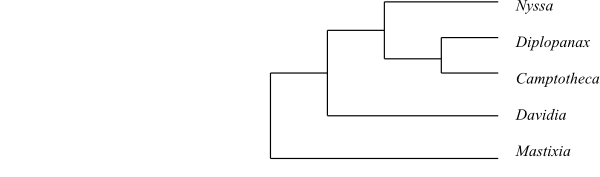

Cladogram of Loasales based on DNA sequence data (Xiang & al. 2011). There was lower support for Nyssaceae being sister-group to the “HLH clade”.

Campanulanae Takht. ex Reveal in Novon 2: 235. 13 Oct 1992; Asteranae Takht., Sist. Filog. Cvetk. Rast. [Syst. Phylog. Magnolioph.]: 451. 4 Feb 1967

[Loasales+[Ericales+[Gentianidae]]]

Cornidae Frohne et U. Jensen ex Reveal in Phytologia 76: 4. 2 Mai 1994; Cornanae Thorne ex Reveal in Phytologia 79: 71. 29 Apr 1996

Fossils Hironoia fusiformis comprises charcoalified gynoecia from the Early Coniacian of Japan The perianth may have been tetramerous or hexamerous and the ovaries developed into trilocular or quadrilocular drupe-like fruits with valvate dehiscence. Eydeia vancouverensis, Obamacarpa enenensis and Edencarpa grandis are fossilized fruits from the Early Coniacian of western North America. These fossils are the oldest known representatives of Loasales. The perianth seems to have been tetramerous or hexamerous and the ovaries developed into trilocular or quadrilocular drupe-like fruits with valvate dehiscence. Possibly the species was closely allied to Nyssaceae. Tylerianthus crossmanensis, from the Turonian of New Jersey, includes half-epigynous flowers with a pentamerous calyx, five stamens with tricolporate pollen grains, five staminodia, an intrastaminal nectariferous disc and two carpels with free recurved styles; the gynoecium developed into a capsule. Suciacarpa xiangae and Sheltercarpa vancouverensis are two fossilized drupaceous fruits, similar to Cornaceae or Nyssaceae, from the Campanian of British Columbia (Canada).

Habit Usually bisexual (sometimes dioecious, rarely monoecious, andromonoecious, polygamomonoecious or polygamodioecious), usually evergreen or deciduous trees or shrubs (sometimes annual or perennial herbs, sometimes climbing, rarely suffrutices). Rarely xerophytic shrubs or aquatic herbs.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio superficially or deeply seated (rarely absent). Vessel elements usually with scalariform (sometimes simple, rarely reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits alternate, scalariform or opposite, simple or bordered pits (rarely absent). Vestured pits at least sometimes present. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids, fibre tracheids or libriform fibres, with simple or bordered pits, septate or non-septate (often also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular (rarely absent). Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates or paratracheal scanty, aliform, confluent, vasicentric or banded (rarely absent). Sieve tube plastids S type or P type? Nodes usually 3:3 or 3:5, trilacunar with three or five leaf traces (rarely multilacunar with five, seven or more traces). Sclereids present. Laticifers usually absent (articulated laticifers sometimes present). Idioblasts with calciumoxalate raphides and mucilage sometimes present. Calciumoxalate as druses, single rhomboidal or prismatic crystals (sometimes crystal sand).

Trichomes Hairs usually unicellular or multicellular, often tuberculate (sometimes glochidiate), uniseriate multiseriate, simple or branched, furcate or multi-armed, stellate (rarely asymmetrically T-shaped or unicellular stinging hairs), sometimes calcified or silicified; multicellular uniseriate glandular hairs sometimes present.

Leaves Alternate (spiral or distichous) or opposite, usually simple (rarely pinnately compound), usually entire (rarely lobed), sometimes coriaceous (rarely ericoid), with conduplicate(-flat), curved (sometimes plicate) or involute ptyxis. Stipules usually absent; leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate, D-shaped or annular. Leaf bases often fused by line. Venation pinnate or palmate. Stomata usually anomocytic (rarely paracytic or absent). Cuticular wax crystalloids (when known) as platelets. Domatia usually as pockets (sometimes as pits or hair tufts). Mesophyll cells often with groups of crystals. Leaf margin serrate or entire (rarely sinuate).

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, thyrsoid, panicle, thyrsopaniculate, raceme-, spike- or head-like, corymbose or umbel-like compound dichasia, often pseudanthia surrounded by petaloid bracts (rarely spike with accrescent bracts).

Flowers Usually actinomorphic (rarely zygomorphic), usually small (sometimes large). Usually epigyny (rarely hypogyny or half epigyny). Sepals usually four or five (rarely six, eight, ten or twelve, or absent), with valvate, imbricate or open aestivation, often persistent, connate. Petals usually four or five (rarely six to eight, ten or twelve, or absent), usually with valvate (sometimes imbricate or contorted) aestivation, free or connate at base (rarely entirely connate). Nectariferous disc intrastaminal (sometimes absent).

Androecium Stamens (two or) four or five (or several times as many as petals; rarely one or up to c. 300 stamens), usually in one whorl (rarely two or more whorls), antesepalous, alternipetalous (rarely diplostemonous or polystemonous). Filaments usually free (rarely connate at base), usually free from tepals (rarely epipetalous). Anthers dorsifixed or basifixed, usually non-versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (rarely mono- or disporangiate), usually introrse (sometimes latrorse, rarely extrorse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits) or poricidal (dehiscing by basal pore). Tapetum secretory. Staminodia usually absent (sometimes petaloid, scale-like or nectariferous).

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains (2–)3–4(–8)-colpor(oid)ate (sometimes colpate or porate, rarely inaperturate), often with H-shaped endoapertures, usually shed as monads (rarely tetrads), usually bicellular (rarely tricellular) at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, perforate, reticulate, imperforate or rugulate, spinulate, striate, verrucate, echinate, gemmate, scabrate or psilate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of one to four (to twelve) connate carpels. Ovary usually inferior (rarely superior or semi-inferior), unilocular to quadrilocular (to decemlocular). Style single, simple or more or less lobate, filiform or columellate, or stylodia two to four, free or connate in lower part. Stigma truncate, capitate or clavate, or bilobate to quadrilobate, papillate or non-papillate, Dry or Wet type. Pistillodium usually absent.

Ovules Placentation usually axile or apical (parietal or apical when ovary unilocular). Ovule one to numerous per carpel or ovary, usually anatropous (rarely amphitropous), pendulous (sometimes ascending), apotropous or epitropous, usually unitegmic (rarely bitegmic), crassinucellar or tenuinucellar. Micropyle often directed upwards. Megagametophyte usually monosporous, Polygonum type (rarely tetrasporous, Fritillaria type). Antipodal cells sometimes persistent or proliferating (rarely absent). Endosperm development usually cellular (rarely nuclear). Endosperm haustoria micropylar and/or chalazal or absent. Embryogenesis (when known) onagrad or solanad.

Fruit A drupe (pyrene with one or two apical germination valves) or a loculicidal and/or septicidal capsule (sometimes a berry, or a syncarp consisting of nutlike drupes), sometimes with persistent calyx (fruits sometimes connate into syncarps).

Seeds Aril absent. Exotesta thin or thick. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm usually copious (rarely very sparse or absent), fleshy, oily and sometimes with hemicellulose. Embryo usually straight, large, well differentiated, with or without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology x = (6–)11–13

DNA Mitochondrial intron coxII.i3 lost.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), cyanidin, Route I secoiridoids, Route II decarboxylated iridoids (e.g. deutzioside), Group I carbocyclic iridoids (geniposide, monotropein, daphylloside), Group II decarboxylated iridoids (e.g. unedoside), Group III carbocyclic iridoids (dihydrocornin, cornin), Group IV carbocyclic iridoids (decaloside, deutzioside, scabroside), Group VI secoiridoids (secologanin, morroniside), Group VII secoiridoids (sweroside), Group IX secoiridoids (camptothecin, ipecac alkaloids), Group X secoiridoids (loganin) (iridoids rarely replaced by, e.g., salidroside), and other iridoid glycosides, monomerous iridoids (sweroside, 8-epi-kingiside, loganin, loganic acid etc.; in Mentzelia iridoids synthesized from epoxydecaloside and decaloside), ellagic and gallic acids, tannins, quinazolinone alkaloids (febrifugine, isofebrifugine), isoquinoline alkaloids (emetic alkaloids, based on secoiridoids: alangiside, tubulosine), ursolic acid, saponins (also triterpene saponins), petroselinic acid, and arbutin present. Tyrosine- or phenylalanine-derived cyanogenic compounds and prodelphinidins rare. Flavones not found. Aluminium sometimes accumulated. Carbohydrates rarely stored as as oligo- or polyfructosans (e.g. inulin).

Systematics Cornales are sister to the remaining Asteridae, a strongly supported position.

Xiang & al. (2011) found strong posterior probability and bootstrap supports for most of the clades in the topology: [[Cornaceae+[Curtisiaceae+Grubbiaceae]]+[Nyssaceae+[Hydro-stachyaceae+[Hydrangeaceae+Loasaceae]]]].

The clade [Cornaceae+[Curtisia+Grubbia]] has the following potential synapomorphies, according to Stevens (2001 onwards): opposite leaves, with leaf bases united by a line or ridge; and flowers small. The South African Grubbiaceae and Curtisiaceae have short lobate style; a single epitropous, tenuinucellar ovule per carpel; pyrene walls consisting of sclereidal cells; and copious endosperm.

The clade [Hydrostachys+[Hydrangeaceae+Loasaceae]] is supported by the potential synapomorphies (Stevens 2001 onwards): placentation parietal; numerous tenuinucellar ovules per carpel; presence of micropylar endosperm haustorium; and presence of caffeoyl ester chlorogenic acid. Hydrangeaceae and Loasaceae share the following potential synapomorphies: phellogen deeply seated; hairs tuberculate, with calcified walls and basal cell pedestals; leaves opposite; leaf margin with glandular teeth; stamens usually numerous (sometimes twice as many as petals; sometimes initiated as antesepalous triplets); gynoecium with axial/central vascular bundles; stigma Dry type; ovules with endothelium; capsule septicidal; exotestal cells variously elongated, with thickened inner walls; absence of intron in mitochondrial gene coxII.i3; presence of flavonols; similar Route I secoiridoids and Route II decarboxylated iridoids (presence of C-8 iridoid glucosides; C-9 iridoids keeping C-11, e.g. deutzioside); and absence of ellagic acid.

Cornaceae and Nyssaceae have often been regarded as sister-groups with support from the following potential synapomorphies: hairs unicellular, T-shaped; calyx small; pollen grains with complex endoaperture, with pore united with two lateral thinner regions parallel to colpus; short style; and presence of Route I secoiridoids and triterpene saponins.

|

Cladogram of Loasales based on DNA sequence data (Xiang & al. 2011). There was lower support for Nyssaceae being sister-group to the “HLH clade”. |

CORNACEAE Bercht. et J. Presl |

( Back to Loasales ) |

Alangiaceae (DC.) DC. in D. F. L. von Schlechtendal in Linnaea 2: 505. Aug-Oct 1827 [’Alangieae’], nom. cons.; Cornales Link, Handbuch 2: 2. 4-11 Jul 1829 [’Cornaceae’]

Genera/species 2/c 87

Distribution Temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere, tropical Central and East Africa, Madagascar, the Mascarene Islands, subtropical and tropical Asia, Malesia to New Guinea and nearby islands, eastern Australia, Melanesia.

Fossils Leaves and fruits of Cornus are known from the Paleocene of North America and Russia, and wood, leaves, pollen grains and fruits of Alangium have been found in Eocene (possibly also Maastrichtian and Paleocene) layers of western North America and Europe. Cenozoic records of Cornaceae from both Europe and North America are numerous. Cornus quadrilocularis from the Eocene has quadrilocular fruits.

Habit Usually bisexual (in Alangium grisolleoides and some species of Cornus dioecious), evergreen or deciduous trees or shrubs (Cornus suecica and C. canadensis are stoloniferous perennial herbs or suffrutices; some species of Alangium are lianas).

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio superficial. Vessel elements usually with scalariform (in Alangium usually simple) perforation plates; lateral pits usually alternate (in Cornus often scalariform or opposite), simple (Alangium) or bordered (Cornus) pits. Vestured pits present. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids, fibre tracheids or libriform fibres (in Alangium), with simple (Alangium) or bordered (Cornus) pits, non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma usually apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates (in Alangium sometimes paratracheal scanty, aliform, confluent, vasicentric or banded). Tyloses frequent. Sieve tube plastids S type or P type? Nodes 3: 3 or 3:5, trilacunar with three or five leaf traces. Sclereids present. Mucilage cells sometimes present. Laticifers usually absent (in Alangium articulated laticifers present). Calciumoxalate as druses and/or prismatic crystals (sometimes crystal sand).

Trichomes Hairs usually unicellular, in Cornus furcate and calcified, often with crystalliferous walls, in Alangium uniseriate or branched (sometimes stellate or glandular, at least in one species of Alangium asymmetrically T-shaped).

Leaves Alternate (usually spiral; in Alangium sometimes distichous) or opposite (almost all species of Cornus), simple, usually entire (rarely lobed), sometimes coriaceous, with conduplicate(-flat), curved (sometimes curved-plicate) or involute ptyxis. Stipules present or absent; leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate, D-shaped or annular; petiole sometimes with medullary bundle. Leaf bases often pairwise fused via transverse line. Venation pinnate or palmate, often actinodromous. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Domatia usually as pockets (sometimes pits or hair tufts). Mesophyll cells in Alangium often with groups of crystals (visible as translucent dots). Leaf margin usually entire (rarely sinuate). Hairs often stellate, cell walls often crystalliferous.

Inflorescence Terminal or axillary, thyrsopaniculate, corymbose or head- or umbel-like, often as pseudanthia surrounded by four white showy petaloid bracts.

Flowers Actinomorphic, usually small. Epigyny. Sepals usually four or five (rarely eight or ten), with valvate or open aestivation, connate into cupular calyx. Petals usually four or five (rarely eight or ten), usually with valvate (rarely contorted) aestivation, usually free (rarely connate at base). Nectariferous disc intrastaminal (in Alangium sometimes absent).

Androecium Stamens usually four or five (rarely up to c. 40), in one whorl, usually antesepalous, alternipetalous (in Alangium four times as many as sepals). Filaments usually free (rarely connate at base), usually free from tepals (rarely adnate to petals). Anthers usually dorsifixed (in Alangium moniliform, usually basifixed), usually non-versatile, tetrasporangiate, introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains (2–)3–4(–8)-colpor(oid)ate (in Alangium sometimes colpate or porate), with complex H-shaped endoapertures (pore united with two lateral thinner regions parallel to colpus), usually shed as monads (rarely as tetrads), bicellular at dispersal; pollen grains often with starch. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, imperforate (sometimes spinulate) or perforate (in Alangium often reticulate to rugulate, striate and verrucate or gemmate).

Gynoecium Pistil composed of one to four connate carpels. Ovary inferior, unilocular to quadrilocular (in Alangium usually unilocular). Style single, simple, filiform or columellate, or stylodia two to four, free or connate in proximal part. Stigma truncate, capitate or clavate, or bilobate or trilobate, non-papillate, Dry type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation usually axile or apical (parietal or apical when ovary unilocular). Ovule one per carpel or ovary, usually anatropous (rarely hemianatropous), pendulous, apotropous, unitegmic, usually crassinucellar (in red-fruited species of Cornus tenuinucellar). Micropyle directed upwards. Integument in Alangium approx. six cell layers thick. Hypostase absent. Parietal tissue approx. three cell layers thick (absent in red-fruited species of Cornus). Megasporocytes usually single (archespore sometimes multicellular). Megagametophyte usually monosporous, Polygonum type (in some species of Cornus tetrasporous, 8-nucleate, Fritillaria type, with polyploid antipodal cells). Antipodal cells usually not proliferating (in Alangium sometimes proliferating up to twelve or more cells). Endosperm development usually cellular (in Alangium lamarckii nuclear). Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A one- or two-seeded drupe, with sclerotized pyrene walls (sometimes a berry), sometimes with persistent calyx (fruits sometimes connate into syncarps). Endocarp usually bilocular, with spheroidal cells.

Seeds Aril absent. Testa membranous, with strongly compressed elongate cells (in Alangium vascularized, approx. six cell layers thick). Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, fleshy, oily and sometimes with hemicellulose. Embryo straight, large, well differentiated, with chlorophyll. Cotyledons two (in Alangium foliaceous). Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = (8–)11 (22 in Cornus canadensis)

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), cyanidin, Route I secoiridoids, Route II decarboxylated iridoids, Group I carbocyclic iridoids (geniposide and monotropein), Group III carbocyclic iridoids (dihydrocornin and cornin), Group VI secoiridoids (secologanin and morroniside), Group VII secoiridoids (sweroside), Group IX secoiridoids (ipecac alkaloids), Group X secoiridoids (loganin) (Alangium and blue-fruited species of Cornus lack iridoids which are replaced by, e.g., salidroside), ellagic and gallic acids, tannins, isoquinoline alkaloids (emetic alkaloids, based on secoiridoids: alangiside, tubulosine, in Alangium), saponins (including triterpene saponins), ursolic acid, and petroselinic acid present. Cyanogenic compounds not found. Inulin present in some species of Cornus. Aluminium accumuled in some species.

Use Ornamental plants, fruits (Cornus mas etc.), timber.

Systematics Cornus (c 60; temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere, few species in Africa and South America), Alangium (27; tropical Africa, northeastern Madagascar, China to eastern Queensland, northeastern New South Wales and New Caledonia).

Cornaceae are sister-group to [Curtisiaceae+Grubbiaceae].

CURTISIACEAE (Harms et Engl.) Takht. |

( Back to Loasales ) |

Genera/species 1/1

Distribution South Africa (the Western Cape Province from the Cape Peninsula to the Uniondale district and the Clanwilliam district), southeastern Africa to Mozambique.

Fossils Uncertain. Fossil fruits reported from the Early Eocene of England (the London Clay) have been assigned to Curtisia (Manchester & al. 2007).

Habit Usually bisexual (rarely dioecious), evergreen tree. Abaxial side of leaves ferrugineous velvety tomentose.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen? Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform or opposite, bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements ? with bordered pits, non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates. Sieve tube plastids S type? Nodes 3:3?, trilacunar with three? leaf traces. Wood ray cells with prismatic calciumoxalate crystals.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular.

Leaves Opposite, simple, entire, coriaceous, with flat ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection annular; petiole with medullary strands. Leaf bases connate via transverse ridge. Venation pinnate. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids as platelets? Leaf margin serrate.

Inflorescence Terminal, thyrsopaniculate.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Epigyny. Sepals four, small, with open aestivation, connate. Petals four, with (sub)valvate aestivation, free. Nectariferous disc intrastaminal, quadrangular, densely hairy.

Androecium Stamens four, antesepalous, alternipetalous. Filaments subulate, free from each other and from tepals. Anthers dorsifixed, versatile?, tetrasporangiate, introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains tricolporate, with H-shaped endoapertures, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum, imperforate (pseudoperforate).

Gynoecium Pistil composed of four connate carpels. Ovary inferior, quadrilocular. Style single, simple, short. Stigma quadrilobate, type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation apical. Ovule one per carpel, anatropous, pendulous, epitropous, unitegmic, crassinucellar. Micropyle directed upwards. Integument ? cell layers thick. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development cellular. Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A four-seeded quadrilocular drupe (dehiscing at maturation) with persistent calyx.

Seeds Aril absent. Exotesta collapsed. Endotesta tanniniferous. Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, oily. Embryo elongate, small, straight, well differentiated, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Germination?

Cytology n = 13

DNA A deletion identical to that found in Grubbia.

Phytochemistry Insufficiently known. Route I secoiridoids, proanthocyanidins and ellagitannins present. Cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Wheels, weapons.

Systematics Curtisia (1; C. dentata; Northern Province, Mpumalanga, KwaZulu-Natal, Western and Eastern Cape, Swaziland, Mozambique)

Curtisia is sister to Grubbia (Grubbiaceae).

GRUBBIACEAE Endl. ex Meisn. |

( Back to Loasales ) |

Ophiraceae Arn. in J. Bot. (Hooker) 3: 266. Feb 1841 [’Ophiriaceae’]; Grubbiales Doweld, Tent. Syst. Plant. Vasc.: li. 23 Dec 2001

Genera/species 1/3

Distribution Southwestern South Africa.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, evergreen shrubs, in Grubbia tomentosa with a lignotuber near the ground surface. Xerophytes.

Vegetative anatomy Lateral roots without distinct endodermis. Phellogen ab initio superficial. Vessel elements with scalariform perforation plates; lateral pits alternate or scalariform, simple pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids with simple pits, non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate and multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse, or paratracheal scanty, or absent. Sieve tube plastids S type? Nodes 3:3?, trilacunar with three? leaf traces. Wood rays with prismatic calciumoxalate crystals.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate.

Leaves Opposite, simple, entire, ericoid with strongly revolute leaf margins, coriaceous, with ? ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Leaf bases connate via transverse ridge. Venation pinnate or leaves one-veined. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids as narrow elongate platelets. Calciumoxalate as druses and single rhomboidal crystals. Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescence Axillary, capitate or conical, compound, few- to many-flowered, dichasial. Ovaries within each inflorescence connate or connivent. Radial bracts absent.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Epigyny. Sepals usually four (sometimes six), with valvate aestivation, free. Petals absent. Nectariferous disc at apex of ovary, pubescent or papillate.

Androecium Stamens usually 4+4 (rarely 6+6), diplostemonous. Filaments linear; four longer filaments antesepalous and adnate at base to sepals; four shorter filaments alternisepalous and free from sepals. Anthers dorsifixed, gradually inverted, versatile?, disporangiate (monothecal), with peripheral microsporangia sterile, introrse (seemingly extrorse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory? Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous? Pollen grains tricolporate, with H-shaped endoapertures?, shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum, imperforate, psilate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of two connate transversely orientated carpels. Ovary inferior, ab initio bilocular, finally unilocular in upper part. Style single, simple, short. Stigma capitate or bifid, type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation ab initio axile-apical (later free central). Ovule one per carpel, anatropous, pendulous, epitropous, unitegmic, tenuinucellar. Micropyle long. Integument ? cell layers thick. Hypostase chalazal. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development cellular. Endosperm haustoria micropylar and chalazal. Embryogenesis?

Fruit A cone-shaped syncarp (coenocarp) consisting of two or several connate one-seeded nutlike druplets.

Seeds Aril absent. Exotesta thin. Endotesta? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, oily, with cutinized surface. Embryo straight, large, well differentiated, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two, short. Germination?

Cytology n = ?

DNA A deletion identical to that found in Curtisia.

Phytochemistry Virtually unknown. Tannins present. Iridoids and flavonoids not found?

Use Unknown.

Systematics Grubbia (3; G. rosmarinifolia, G. rourkei, G. tomentosa; Western and Eastern Cape).

Grubbia is sister to Curtisia (Curtisiaceae).

HYDRANGEACEAE Dumort. |

( Back to Loasales ) |

Hortensiaceae Martinov, Tekhno-Bot. Slovar: 315. 3 Aug 1820 [’Hortensieae’]; Hortensiales Bercht. et J. Presl, Přir. Rostlin: 260. Jan-Apr 1820 [‘Hortensiae’]; Philadelphaceae Martinov, Tekhno-Bot. Slovar: 478. 3 Aug 1820 [’Phyladelpheae’]; Philadelphales Link, Handbuch 2: 70. 4-11 Jul 1829 [‘Philadelpheae’]; Hydrangeales Lindl. in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp. Regn. Veg.: 63. Sep-Oct 1835 [‘Hydrangeaceae’]; Kirengeshomaceae Nakai, Chosakuronbun Mokuroku [Ord. Fam. Trib. Nov.]: 245. 20 Jul 1943

Genera/species 9/195–200

Distribution The Caucasus, East Asia to Japan and the Russian Far East, few species in Southeast Asia to New Guinea, temperate and subtropical North America, southern Mexico, Central America, the Andes to central Chile, with their highest diversity in China and North America.

Fossils Leaves and reproductive structures of Hydrangea are known from the Eocene and Oligocene of Europe and North America and fossils reminiscent of Dichroa and Schizophragma have been found in Europe. Fruit and flower, Tylerianthus crossmanensis, assigned to Hydrangeaceae were described from coal layers of Turonian age in New Jersey. Fossil fruits of Hydrangea containing winged seeds were recovered from Eocene layers in Oregon (Manchester 1994).

Habit Usually bisexual (in Broussaisia polygamodioecious), evergreen or deciduous trees or shrubs, often climbing and twining (rarely suffrutices or perennial herbs). Bark usually exfoliating.

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio inner-cortical or outer-pericyclic. Endodermis absent. Vessel elements usually with scalariform (sometimes also simple or reticulate, rarely simple only) perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform, opposite or alternate, simple or bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids, fibre tracheids or libriform fibres usually with bordered (sometimes simple) pits, septate or non-septate (also vasicentric tracheids). Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, homocellular or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma apotracheal (with few cells around vessel elements) diffuse, or paratracheal scanty or vasicentric, or absent. Tyloses (sclerotic) sometimes frequent. Sieve tube plastids usually S type (rarely P type?). Nodes usually 3:3, trilacunar with three leaf traces (sometimes multilacunar with 5 or ≥7 traces). Idioblasts with calciumoxalate raphides and mucilage present in Hydrangeeae. Calciumoxalate as druses or raphides present in many representatives.

Trichomes Hairs usually unicellular, tuberculate (with tuberculate surface), pointed apex and multicellular base (with basal cell pedestals), sometimes with calcified or silicified walls, sometimes furcate or multi-armed (in Kirengeshoma unicellular furcate, in Deinanthe multicellular furcate, in Deutzia unicellular stellate, in Pileostegia and some species of ‘Hydrangea’ multicellular stellate, in some species of Philadelphus multicellular uniseriate, in Broussaisia tufted).

Leaves Usually opposite (rarely alternate or verticillate), simple, usually entire (rarely lobed), with conduplicate or supervolute ptyxis. Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection usually annular (sometimes arcuate); petiole sometimes with reversed bundles. Leaf bases pairwise connate by transverse line. Venation usually pinnate (rarely palmate), acrodromous, brochidodromous (rarely craspedodromous or eucamptodromous). Stomata anomocytic or paracytic. Cuticular wax crysalloids? Secretory cavities present or absent. Mesophyll with calciumoxalate raphides. Domatia (in ‘Hydrangea’ and Philadelphus) as hair tufts. Leaf margin serrate or entire; teeth with clear apex with foramen (teeth in Decumaria, Deutzia, and Philadelphus gland-tipped).

Inflorescence Terminal often corymb, capitate, thyrsoid, or panicle, often as pseudanthia with sterile marginal florets with large showy petaloid sepals (flowers rarely solitary).

Flowers Actinomorphic. Usually epigyny (sometimes hypogyny or half epigyny). Sepals four or five (to twelve), with valvate or imbricate aestivation, persistent, usually connate at base. Petals four or five (to twelve), with valvate, imbricate or contorted aestivation, usually free or connate only at base (in Pileostegia and Hydrangea anomala often entirely connate). Nectariferous disc intrastaminal; nectary vascularized.

Androecium Stamens usually two or several times the number of (rarely as many as) petals (sometimes up to c. 50; in Carpenteria up to c. 200), (staminal primordia) primarily antesepalous, diplostemonous or polystemonous (rarely haplostemonous). Filaments linear, subulate or filiform, free or connate at base into tube, free from tepals (sometimes with small appendages). Anthers usually basifixed (sometimes dorsifixed), non-versatile?, tetrasporangiate, introrse to latrorse, poricidal (dehiscing by basal pore); connective sometimes prolonged. Tapetum secretory. Staminodia present in female flowers of Broussaisia.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tricolpor(oid)ate (in some species of ‘Hydrangea’ tricolpate), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate or semitectate, with columellate infratectum, perforate to reticulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (one to) three to five (to twelve) connate carpels (carpels in Deutzia, Dichroa and Philadelphus alternisepalous, four; when carpels three then odd carpel adaxial; in ‘Hydrangea’ odd carpel abaxial; in Broussaisia carpels antesepalous, five). Ovary usually inferior (sometimes superior or semi-inferior), unilocular to septalocular. Style single, simple, or stylodia two to seven, free or more or less connate. Stigma one, lobate, or stigmas several, linear or capitate, papillate, Dry or Wet type. Pistillodium present in male flowers of Broussaisia.

Ovules Placentation usually axile at base and intrusively parietal above (sometimes entirely axile, rarely entirely parietal or apical). Ovules one, several or numerous per carpel, anatropous, pendulous or ascending, apotropous, unitegmic, tenuinucellar. Integument (three to) five to seven (to ten) cell layers thick. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Some genera with megagametophyte protruding out of micropyle and with micropylar haustoria. Antipodal cells often persistent. Chalazal haustorium from antipodal cells present in Kirengeshoma. Endosperm development usually cellular (in Fendlera nuclear). Endosperm haustoria in Deutzia and Philadelphus micropylar. Embryogenesis?

Fruit A usually loculicidal and/or septicidal capsule (in Broussaisia and Dichroa a berry).

Seeds Seeds often winged. Aril? Exotestal cells lignified, elongate; theoidal exotestal thickenings present (inner cell walls thickened). Endotesta? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm relatively copious, fleshy. Embryo small, straight, well differentiated, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two. Germination?

Cytology n = 11, 13–18 (or more) – Polyploidy occurring.

DNA Mitochondrial intron coxII.i3 lost.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin?), cyanidin, Route I secoiridoids, Group VI secoiridoids (secologanin), Group I carbocyclic iridoids (daphylloside), Group II decarboxylated iridoids (e.g. unedoside), Group IV carbocyclic iridoids (deutzioside, scabroside), Group X secoiridoids (loganin), and other iridoid glucosides, tannins, proanthocyanidins (prodelphinidin), quinazolinone alkaloids (febrifugine, isofebrifugine), tyrosine- or phenylalanine-derived cyanogenic compounds, and arbutin present. Ellagic acid not found. Aluminium accumulated in some species.

Use Ornamental plants, medicinal plants.

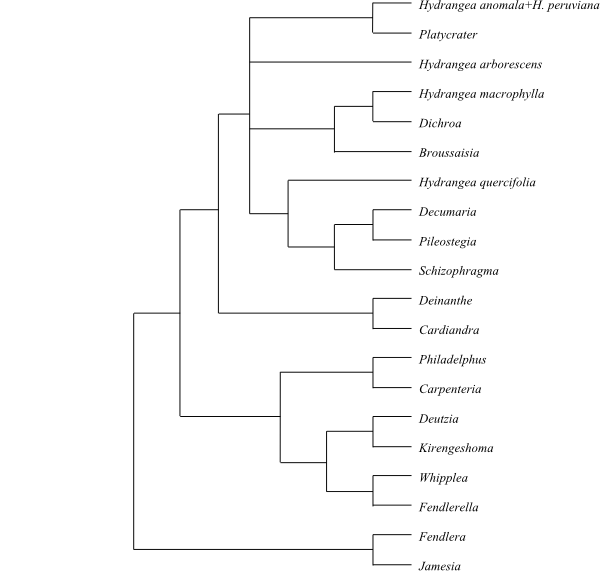

Systematics Hydrangeaceae are sister group to Loasaceae.

Jamesioideae are sister to [Hydrangeeae+Philadelpheae].

Jamesioideae L. Hufford in Intern. J. Plant Sci. 162(4): 844. 18 Jun 2001

2/5. Fendlera (3; F. rigida, F. rupicola, F. wrightii; southwestern United States, northern Mexico), Jamesia (2; J. americana, J. tetrapetala; western United States). – Western United States, northern Mexico. Sepals valvate. Petals free. Stamens ten. Pistil composed of (three or) four or five carpels. Stylar branches more or less separate. Endosperm development nuclear (Fendlera). n = 16. Myricetin sometimes present.

Hydrangeoideae Burnett, Outlines Bot.: 732, 1092, 1135. Feb 1835 [’Hydrangidae’]

7/190–195. Nodes also 5:5, 7(+):7(+). Distribution as for Hydrangeaceae. Idioblasts with calciumoxalate raphides (raphide sacs) usually present. Hairs sometimes stellate. Petiole vascular bundle transection usually annular (sometimes arcuate); petiole sometimes with inverted bundles, often with medullary bundles. Sepals with valvate aestivation. Petals usually with valvate or imbricate (sometimes contorted) aestivation. Stamens sometimes in fascicles of five. Filaments sometimes winged. Integuments three to five cell layers thick. Fruit sometimes a berry, a loculicidal capsule or dehiscing along sides. Endosperm base lignified.

Hydrangeeae DC., Prodr. 4: 13. late Sep 1830 [‘Hydrangeae’]

1/65–70. Hydrangea (65–70; warm-temperate regions on the Northern Hemisphere south to Malesia, the Hawaiian Islands and Chile; incl. Hydrangea s.str. in America and the Himalayas to Japan and the Philippines, Cardiandra in East Asia, Deinanthe in central China and Japan, Platycrater arguta in Japan, Dichroa in China, Southeast Asia and Malesia to New Guinea, Broussaisia arguta on the Hawaiian Islands, Schizophragma in the Himalayas to the Korean Peninsula, Japan and Taiwan, Decumaria sinensis in central China and D. barbara in southeastern United States, and Pileostegia in East Asia). – Idioblasts with calciumoxalate raphides and mucilage present. Marginal flowers of inflorescence in Hydrangea sometimes with petaloid sepals. Petals with valvate aestivation, not clawed. Pistil in some species (e.g. H. anomala, H. peruviana and ‘Platycrater’) composed of two carpels. Stylodia free. Fruit usually a loculicidal capsule (sometimes berry-like). Testa in some species (e.g. H. macrophylla and ‘Dichroa’) with sinuous anticlinal cell walls and special elongate parallel striations. Myricetin present (‘Decumaria’). – The clade [‘Cardiandra’+’Deinanthe’] is sister-group to the remaining Hydrangea..

Philadelpheae DC. ex Duby, Bot. Gall. 1: 184. 12-14 Apr 1828

6/c 125. ‘Philadelphus’ (c 60; temperate and subtropical regions on the Northern Hemisphere to Central America, with their highest diversity in North America, one species, P. coronarius, in Europe; paraphyletic), Carpenteria (1; C. californica; central Sierra Nevada in California); Fendlerella (1; F. utahensis; southwestern United States), Whipplea (1; W. modesta; the Pacific coast of United States), Deutzia (c 60; temperate Asia south to the Philippines, mountain regions in Mexico), Kirengeshoma (2; K. koreana, K. palmata; eastern China, the Korean Peninsula, Japan). – Temperate and subtropical regions on the Northern Hemisphere, with their highest diversity in Southeast Asia to the Philippines. Stomata sometimes laterocytic. Sepals sometimes connate. Petals with imbricate aestivation. Stamens initiated as five common primordia (in Philadelphus with centrifugal development). Stylodia connate to free. Ovule with a single lateral layer of megasporangial tissue. Megagametophyte protruding from megasporangium. – The clade [Philadelphus+Carpenteria] is sister to the remaining Philadelpheae.

|

Cladogram of Hydrangeaceae based on morphology and DNA sequence data (Soltis & al. 1995; Hufford & al. 2001). |

HYDROSTACHYACEAE (Tul.) Engl. |

( Back to Loasales ) |

Hydrostachyales Diels ex Reveal in Phytologia 74: 174. 25 Mar 1993

Genera/species 1/22

Distribution Tropical and subtropical regions of southern Africa, Madagascar.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Usually dioecious (rarely monoecious), usually perennial (sometimes annual) submersed aquatic herbs with disc-shaped tuberous stem. Monocarpic.

Vegetative anatomy Main root not developed. Adventitious roots fibrous, anchoring. Phellogen absent. Secondary lateral growth absent. Xylem and phloem strongly reduced. Primary vessel elements (in young stems) with annular or spiral cell wall thickenings (older stems with only schizogenous cavities containing vessel remnants). Imperforate tracheary xylem elements? Wood rays absent. Axial parenchyma absent? Sieve tube plastids S type? Nodes? Calciumoxalate druses present.

Trichomes Hair tufts present at floral bases.

Leaves Alternate (spiral, in basal rosette), simple or one to three times deeply pinnately compound, often with filiform or vesicular leaflets and numerous small verrucate, filiform or scale-like or fringed appendages on rachis, ligulate at base, with ? ptyxis; floating leaves with enlarged base. Stipule-like outgrowth (ligule?, on floating leaves) usually one, membranous, intrapetiolar (sometimes two, lateral); leaf sheath absent. Petiole with central vascular bundle and numerous small bundles supporting outgrowths. Venation pinnate? Stomata absent. Cuticular waxes absent? Leaf margin entire.

Inflorescences Terminal spikes. Bracts persistent and accrescent.

Flowers Female flowers zygomorphic, small. Sepals absent. Petals absent. Nectary absent. Disc absent.

Androecium Stamen one, apically bifid (or two? largely connate). Filament short. Anther basifixed, non-versatile, one split tetrasporangiate (or two? disporangiate, monothecal), extrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory, with binucleate cells. Staminodia absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains inaperturate, shed as tetrads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate? infratectum, microspinulate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of two connate transversely arranged collateral carpels. Ovary unilocular. Stylodia two, subulate or filiform, persistent, usually free (sometimes connate at base), impressed into apex of ovary. Stigmas two, elongate, papillate, type? Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation parietal. Ovules several to numerous per ovary, anatropous, unitegmic, tenuinucellar. Integument approx. five cell layers thick. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Antipodal cells not formed. Endosperm development cellular. Endosperm haustorium micropylar. Embryogenesis onagrad.

Fruit A septicidal capsule.

Seeds Seeds very small. Aril absent. Seed coat exotestal. Exotestal cells with strongly thickened and mucilaginous (pectinous) outer walls. Endotesta? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm very sparse or absent. Embryo?, chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Radicula absent. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 10–12

DNA

Phytochemistry Insufficiently known. Flavonols (kaempferol etc.), caffeic acid, and caffeoyl ester chlorogenic acid present. Iridoids and alkaloids not found.

Use Unknown.

Systematics Hydrostachys (22; tropical and subtropical regions of southern Africa, Madagascar).

The sister-group relationships of Hydrostachys have been difficult to resolve. Sequences are often hard to align together with other clades, even within Cornales. In some analyses Hydrostachys is placed adjacent to or even within Hydrangeaceae. Other analyses place Hydrostachys as sister to Loasaceae. Sometimes, Hydrostachys has often been placed in Plantaginales (see, e.g., Burleigh & al. 2009).

LOASACEAE Juss. |

( Back to Loasales ) |

Gronoviaceae A. Juss. in V. V. D. d’Orbigny, Dict. Univ. Hist. Nat. 6: 340. 1845 [‘Gronovieae’]; Cevalliaceae Griseb., Grundr. Syst. Bot.: 136. 1-2 Jun 1854; Loasineae Engl., Syllabus, ed. 2: 156. Mai 1898; Loasanae R. Dahlgren ex Reveal in Phytologia 79: 71. 29 Apr 1996

Genera/species 24/285–315

Distribution Temperate, subtropical and tropical regions of America from southwestern Canada to Argentina and Chile, the West Indies, the Galápagos Islands, the Marquesas Islands; one species in southwestern Africa; one species in northeastern Ethiopia, Somalia and southwestern Arabian Peninsula.

Fossils Unknown.

Habit Bisexual, usually annual or perennial herbs, often climbing (rarely shrubs, lianas or a succulent tree with often exfoliating bark).

Vegetative anatomy Roots fibrous or tuberculate (main root in Nasa ephemeral and replaced by adventitious roots). Phellogen ab initio deeply seated (inside pericycle). Secondary lateral growth often absent. Vessel elements usually with simple (rarely scalariform or other type) perforation plates; lateral pits alternate or scalariform. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids with bordered pits (sometimes with reduced margins), usually non-septate (in Placothira septate? or living?). Wood rays usually multiseriate (sometimes uniseriate), homocellular or heterocellular. Axial parenchyma usually apotracheal diffuse (rarely paratracheal vasicentric, or absent). Wood elements often storied. Sieve tube plastids S type. Nodes? Cystoliths (with calciumcarbonate or silica) and calciumoxalate as druses or raphides frequent.

Trichomes Unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate, often with calcified or silicified cell walls, scabrid-glochidiate and tuberculate hairs provided with prickles and hooks, sometimes unicellular stinging hairs (hairs rarely T-shaped or dendritic); glandular hairs multicellular uniseriate flexible (often with basal cystolith, basal cell pedestals).

Leaves Alternate (spiral) or opposite, usually simple (rarely pinnately or palmately compound), entire or lobed, with ? ptyxis. Stipules? and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate or annular; petiole with wing bundles. Venation pinnate to palmate. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Leaf margin usually serrate (sometimes sinuate), with hydathodal teeth (glandular teeth?; rarely entire). Calciumoxalate druses present.

Inflorescence Usually terminal (rarely axillary), thyrsoid, raceme-, spike- or head-like cymose (in Petalonyx racemose), or flowers solitary.

Flowers Usually actinomorphic, often large. Hypanthium present. Receptacle hollow. Epigyny to almost hypogyny. Sepals usually five (rarely four or eight), with imbricate or valvate (contorted?) aestivation, usually persistent and often accrescent, connate. Petals usually five (rarely four or eight), with imbricate, valvate (induplicate-valvate?) or contorted aestivation, flat or cymbiform, usually clawed, sometimes with apical outgrowths, usually free (sometimes connate in lower part). Nectariferous disc annular or cupulate or absent. Nectaries often staminodial. C-A-synorganization usually present.

Androecium Stamens usually five, 5+5 or numerous (rarely four, eight or up to c. 300), in one or several whorls (outer staminal whorl in some species modified into corona), staminal primordia primarily antesepalous (antepetalous stamens developing from flanks of antesepalous staminal primordia), haplostemonous, obdiplostemonous or polystemonous. Filaments filiform to subulate, free or connate at base and tubular, sometimes in antepetalous groups, free from or adnate to petals. Anthers basifixed, non-versatile?, monosporangiate to tetrasporangiate, introrse or latrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits). Tapetum secretory. Staminodia petaloid, scale-like, modified into antepetalous nectaries (sometimes three or more connate to large showy nectary with mouth directed against floral centre) or absent.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tricolpate or tricolporate (sometimes porate?; in Chichicaste tricolporoidate), shed as monads, bicellular or tricellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum, punctate, rugulate, striate and/or reticulate, spinulate, echinate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (three to) five (to seven) connate antesepalous carpels (when three carpels, then median carpel adaxial; sometimes seemingly monocarpellate, pseudomonomerous). Ovary inferior to semi-inferior, usually unilocular (sometimes bilocular, rarely trilocular to septalocular). Style single, filiform, hollow, simple or lobate. Stigma clavate, punctate or bilobate to quinquelobate, papillate, Dry? type. Pistillodium absent.

Ovules Placentation usually parietal (often intrusively parietal, sometimes apical [pseudomonomery], rarely axile [when ovary multilocular]). Ovules (one to) numerous per ovary, anatropous to hemitropous, epitropous, unitegmic, usually tenuinucellar (in Gronovia and Petalonyx crassinucellar?). Micropyle long. Integument twelve to 17 cell layers thick. Obturator present at least in Petalonyx thurberi. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Antipodal cells persistent. Endosperm development cellular. Endosperm haustoria micropylar and chalazal, usually well developed. Embryogenesis solanad.

Fruit Usually a loculicidal or septicidal capsule (sometimes spirally twisted; in Gronovioideae a cypsela).

Seeds Seed sometimes winged. Aril absent. Testa in some species of Loasoideae fenestrate with very tall anticlinal cell walls. Exotestal cells elongate, with thickened inner walls. Testa sometimes with thickened hypodermal layer. Endotesta? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm usually copious, oily and fatty (in Gronovioideae sparse or absent). Embryo usually straight (sometimes curved), well differentiated, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons two, hairy, with midvein ending in hydathodal tooth. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = (19? –)21 (Eucnide); n = 6, 12–14, 18, 24, 28 (Loasoideae); n = 9–11, 14, 18, 27, 36 (Mentzelioideae); n = 13, 22, 23, 37 (Gronovioideae) – Polyploidy and dysploidy frequent.

DNA Intron absent from mitochondrial gene coxII.i3.

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), Route I secoiridoids, Route II decarboxylated iridoids, Group IV carbocyclic iridoids (decaloside, deutzioside), monomerous iridoids (sweroside, 8-epi-kingiside, loganin, loganic acid etc.; in Mentzelia iridoids synthesized from epoxydecaloside and decaloside), and caffeic acid present. Myricetin, ellagic acid, tannins, proanthocyanidins, alkaloids, saponins, and cyanogenic compounds not found.

Use Ornamental plants, medicinal plants.

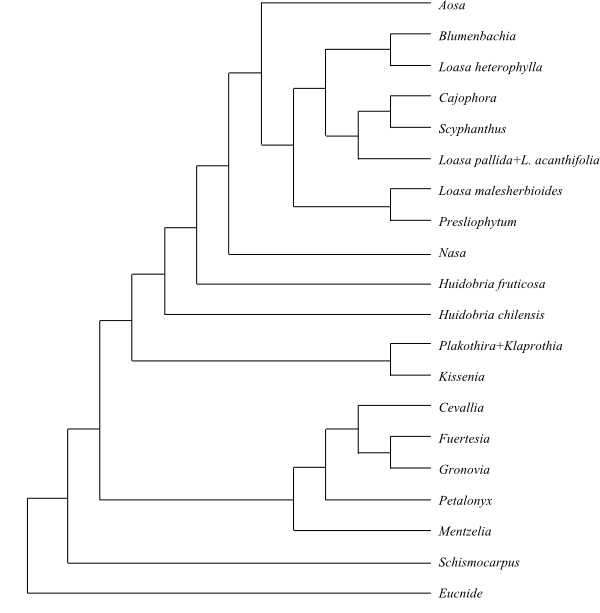

Systematics Loasaceae are sister-group to Hydrangeaceae.

A strongly supported topology is the following: [Eucnide+[Schismocarpus+[Loasoideae+[Mentzelioideae+Gronovioideae]]]].

Eucnide

1/13? Eucnide (13?; southwestern United States, Mexico). – Petals usually free (sometimes connate). Stamens centripetally developed. Filaments connate at base (sometimes adnate to petals). Fruit a septicidal capsule. n = (19? –)21. – Eucnide is sister to the remaining Loasaceae.

[Schismocarpus+[Losasoideae+[Mentzelioideae+Gronovioideae]]]

Schismocarpus

1/1. Schismocarpus (1; S. pachypus; the Oaxaca Province in Mexico). – Stamens ten. Filaments shorter than anthers. Carpels antepetalous. Stigma capitate. n = ?

[Loasoideae+[Mentzelioideae+Gronovioideae]]

Carpels three to five; when three carpels, then median carpel adaxial.

Loasoideae Gilg in Engler et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. III, 6a: 107. 27 Feb 1894

17/205–225. Huidobria (1; H. chilensis; northern Chile), ’Huidobria’ fruticosa (northern Chile), Kissenia (2; K. arabica: Ethiopia, Somalia, southwestern Arabian Peninsula; K. capensis: Namibia, Northern Cape), Xylopodia (1; X. klaprothioides; Peru), Plakothira (3; P. frutescens, P. parviflora, P. perlmanii; the Marquesas Islands), Nasa (c 100; tropical America), Aosa (7; A. gilgiana, A. parviflora, A. plumieri, A. rostrata, A. rupestris, A. sigmoidea, A. uleana; Hispaniola, eastern Brazil), Loasa (c 25; Mexico to South America), Presliophytum (5; P. arequipense, P. heucheraefolium, P. incanum, P. malesherbioides, P. sessiliflorum; western Peru, northern Chile), Blumenbachia (12; South America), Grausa (5; G. gayana, G. lateritia, G. martini, G. micrantha, G. sagittata; Chile), Pinnasa (>4; P. nana, P. pinnatifida, P. volubilis; Chile, Argentina), Scyphanthus (2; S. elegans, S. stenocarpus; Chile), Cajophora (34–56; the Andes in South America). – Unplaced Loasoideae: Klaprothia (2; K. fasciculata, K. mentzelioides; tropical South America, the Galápagos Islands), Chichicaste (1; C. grandis; Costa Rica to northwestern Colombia). – Africa and southwestern Arabian Peninsula (Kissenia), the Marquesas Islands (Plakothira), North to South America. Calyx and corolla separately shed. Petals cymbiform, clawed. Stamens centripetally and centrifugally developed. Fertile stamens in five antepetalous fascicles. Staminodia antesepalous, in outer whorl connate, scale-like, in inner whorl free, stamen-like. Pollen grains not striate? n = 6, 12–14, 18, 24, 28; x = 6.

[Mentzelioideae+Gronovioideae]

C-A-synorganization absent.

Mentzelioideae Gilg in Engler et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. III, 6a: 107. 27 Feb 1894

1/60–70. Mentzelia (60–70; warm-temperate regions in southwestern Canada and the United States, Mexico, Central and South America, the Galapagos Islands). – Calyx and corolla shed as a unit. Stamens centripetally developed. Filaments connate at base. Staminodia dichotomously branched. Endosperm haustoria present. n = 9–11, 14, 18, 27, 36; x = 7.

Gronovioideae M. Roem., Fam. Nat. Syn. Monogr. 2: 6. Dec 1846 [’Gronovieae’]

4/9. Petalonyx (5; P. crenatus, P. linearis, P. nitidus, P. parryi, P. thurberi; southwestern United States, Mexico), Cevallia (1; C. sinuata; southwestern United States, Mexico), Gronovia (2; G. longiflora, G. scandens; Mexico, Central America, tropical South America), Fuertesia (1; F. dominguensis; Hispaniola). – America. Hypanthium usually absent (sometimes present). Petals with valvate aestivation, with a simple vascular trace. Stamens usually five fertile, antesepalous (rarely two stamens and three staminodia). Anthers bifacial. Pistil composed of three connate carpels. Placentation apical. Ovule one per carpel, pendulous, crassinucellar (in Gronovia and Petalonyx). Funicular obturator present. Endosperm haustoria absent. Fruit a cypsela. Testa absent. Endosperm sparse or absent. n = 13, 22, 23, 37. – Petalonyx may be sister to the remainder.

|

Cladogram of Loasaceae baseed on DNA data (Moody & al. 2001; Hufford & al. 2003; Hufford & al. 2005). Kissenia is sometimes recovered as sister to Huidobria chilensis; both taxa lack a deletion of 6 bp present in other investigated Loasoideae. |

NYSSACEAE Juss. ex Dumort. |

( Back to Loasales ) |

Nyssales Juss. in C. F. P. von Martius, Consp. Regn. Veg.: 15. Sep-Oct 1835 [‘Nyssaceae’]; Mastixiaceae Calest. in Webbia 1: 94. 10 Mai 1905; Davidiaceae (Engl.) H.-L. Li in Lloydia 17: 330. 18 Mar 1955; Camptothecaceae Chen 1988, nomen nudum

Genera/species 5/c 32

Distribution Southern India, Sri Lanka, eastern Himalayas to southern China, Southeast Asia, Malesia to the Solomon Islands, eastern and southeastern United States, southern Mexico, with their largest diversity in continental Southeast Asia.

Fossils Fossil pyrenes (endocarps) of Mastixia and other Nyssaceae are present in Campanian to Maastrichtian and Cenozoic layers in the Northern Hemisphere, and particularly frequent from the Eocene and the Oligocene of Eurasia and North America. Thus, fossil Nyssaceae from the Late Cretaceous and the Palaeogene include Amersinia,Beckettia, Browniea,Eomastixia, Ganitroceras, Hironoia,Mastixiocarpus (possibly fossil Diplopanax), Mastixiopsis, Retinomastixia and Tectocarya. During the Cenozoic, Nyssa and Palaeonyssa were widely distributed in the Northern Hemisphere and fossil endocarps of Nyssa were found in Late Cretaceous (Campanian) layers in Alberta and are frequent in Oligocene and Miocene strata. Davidia fruits are known from the Late Cretaceous (Campanian) of Alberta in Canada and Paleocene of North America and Russia.

Habit Bisexual, andromonoecious, polygamomonoecious, dioecious or polygamodioecious, evergreen or deciduous trees, shrubs or lianas (rarely herbs).

Vegetative anatomy Phellogen ab initio superficial. Medulla septated by diaphragms. Cortical vascular bundles present in Mastixia. Vessel elements with scalariform or scalariform-reticulate perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform, opposite or alternate, usually bordered (sometimes simple) pits. Vestured pits? Imperforate tracheary xylem elements fibre tracheids, usually with bordered (sometimes simple) pits, usually non-septate. Wood rays uniseriate or multiseriate, heterocellular. Axial parenchyma usually apotracheal diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates (in Mastixia also paratracheal scanty). Tyloses abundant in Mastixia. Sieve tube plastids S type? Nodes 3:3?, trilacunar with three? leaf traces. Diplopanax and Mastixia have resinous canals with secretory epithel in cortex and medulla. Calciumoxalate as druses and/or prismatic crystals.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular, in Diplopanax and Mastixia often two-branched and often T-shaped; glandular hairs unicellular.

Leaves Usually alternate (spiral; sometimes opposite), simple, entire, with conduplicate ptyxis (Nyssa). Stipules and leaf sheath absent. Petiole vascular bundle transection arcuate or with adaxial plate. Venation pinnate. Stomata sometimes paracytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids? Domatia as pits or pockets. Epidermis with mucilage cells. Mesophyll with sclerenchymatous idioblasts (with sclereids reaching from one epidermis to the next). Leaf margin entire or serrate; teeth with translucent tip with foramen.

Inflorescence Usually terminal (sometimes axillary) thyrsoid, cymose, often racemose, capitate or umbellate to paniculate (flowers rarely solitary), in Davidia pseudanthia surrounded by two white showy petaloid bracts.

Flowers Actinomorphic, small. Epigyny. Sepals four or five (to seven), with open aestivation, small, often persistent, free or slightly connate, or absent (entirely or seemingly?). Petals four or five (to eight), with imbricate or valvate aestivation (when valvate then apically incurved; in Mastixia apically incurved and lobed), free, in female flowers reduced or absent (absent in male and female flowers of Davidia). Nectariferous disc intrastaminal, annular (pulvinate), quadri- or quinquelobate with antepetalous lobes (absent in Davidia).

Androecium Stamens (one to) four to 21 (to 26; in Camptotheca and Diplopanax 5+5), haplostemonous, alternipetalous, or diplostemonous. Filaments filiform or subulate, free from each other and from tepals. Anthers basifixed or dorsifixed, versatile?, not inverted, tetrasporangiate, introrse or latrorse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits); connective in Mastixia apically somewhat prolonged. Tapetum secretory. Staminodia present or absent; female flowers sometimes with staminodia.

Pollen grains Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen grains usually tricolporate (rarely tetracolporate), often with complex H-shaped endoapertures (pore united with two lateral thinner regions parallel to colpus), shed as monads, bicellular at dispersal. Exine tectate, with columellate infratectum, perforate, scabrate.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of (one or) two to ten connate carpels. Ovary inferior, unilocular to decemlocular. Style usually single, short, thick, simple, bifid or trifid (stylodia sometimes two, free or partially connate). Stigmas one to three, sulcate, punctate, capitate or slightly lobate, papillate or non-papillate, Dry type. Pistillodium usually absent.

Ovules Placentation axile to apical (ovary multilocular), or parietal to apical (pseudomonomery). Ovule one per carpel, anatropous, pendulous, epitropous, usually unitegmic (in Davidia rarely bitegmic), usually crassinucellar (in Nyssa tenuinucellar). Micropyle long, directed upwards. Integument eight to ten (to more than 15) cell layers thick. Hypostase present. Megasporocyte usually single (archespore sometimes multicellular). Parietal tissue one to three cell layers thick. Nucellar cap approx. two cell layers thick. Suprachalazal zone strongly elongated. Supraraphal chalaza massive. Megagametophyte monosporous, Polygonum type. Endosperm development cellular (Davidia) or nuclear (Nyssa). Endosperm haustoria? Embryogenesis?

Fruit A usually one-seeded (sometimes two- to six-seeded) drupe, often with valvate dehiscence of endocarp (in Camptotheca samaroid; in Mastixia with resinous canals). Pericarp cells fibrous. Endocarp often laterally invaginated (locule U-shaped in cross-section).

Seeds Seeds in Mastixia U-shaped. Aril absent. Testa multiplicative. Exotesta lignified. Endotesta? Perisperm not developed. Endosperm copious, fleshy, oily and often with hemicellulose. Embryo straight, usually large, well differentiated (in Mastixia small; in Diplopanax C-shaped in cross-section), chlorophyll? Cotyledons two. Germination phanerocotylar.

Cytology n = 11 (Mastixia), 13 (Mastixia), 21 (Davidia), 22 (Nyssa, Camptotheca)

DNA

Phytochemistry Flavonols (kaempferol, quercetin), Route I secoiridoids, Group I carbocyclic iridoids (daphylloside), Group VI secoiridoids (secologanin), Group IX secoiridoids (camptothecine, an alkaloid, present in Camptotheca), Group X secoiridoids (loganin), ellagic and gallic acids, tannins, proanthocyanidins, triterpene saponins, and petroselinic acid (in Diplopanax) present. Cyanogenic compounds not found. Aluminium accumulated in some species.

Use Ornamental plants, medicinal plants, resins (Mastixia), timber.

Systematics Nyssa (8; tropical Asia to China, eastern and southeastern United States, southern Mexico), Camptotheca (1; C. acuminata; southern and southeastern China), Davidia (1; D. involucrata; southwestern China), Diplopanax (2; D. stachyanthus, D. vietnamensis; China, Vietnam), Mastixia (c 20; southern India, Sri Lanka, eastern Himalayas to southern China, Southeast Asia, Malesia to New Guinea and Solomon Islands).

Nyssaceae are sister-group to the clade [Hydrostachyaceae+[Hydrangeaceae+Loasaceae]] with moderately strong support.

|

Cladogram of Nyssaceae based on DNA sequence data (Xiang & al. 1993; Xiang & al. 1998). |

Literature

Ackermann M. 2011. Studies on systematics, morphology and taxonomy of Caiophora and reproductive biology of Loasaceae and Mimulus (Phrymaceae). – Ph.D. diss., Freie Universität Berlin.

Ackermann M, Weigend M. 2006. Nectar, floral morphology and pollination syndrome in Loasaceae subfamily Loasoideae (Cornales). – Ann. Bot. 98: 503-514.

Ackermann M, Weigend M. 2007. Notes on the genus Caiophora (Loasoideae, Loasaceae) in Chile and neighbouring countries. – Darwiniana 45: 45-67.

Ackermann M, Weigend M. 2013. A revision of loasoid Caiophora (Caiophora pterosperma-group, Loasoideae, Loasaceae) from Peru. – Phytotaxa 110: 17-30.

Acuña R, Fließwasser S, Ackermann M, Henning T, Luebert F, Weigend M. 2017. Phylogenetic relationships and generic re-arrangements in “South Andean Loasas” (Loasaceae). – Taxon 66: 365-378.

Adams JE. 1949. Studies in the comparative anatomy of the Cornaceae. – J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 65: 218-244.

Agababyan VS. 1961. A contribution to the palynomorphology of the family Hydrangeaceae Dum. – Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR, Ser. Biol. 14(11): 17-26. [In Russian]

Albach DC, Soltis DE, Chase MW, Soltis PS. 2001 Phylogenetic placement of the enigmatic angiosperm Hydrostachys. – Taxon 50: 781-805.

Alverson E. 1985. Taxonomy review IV, Cornus unalaschkensis. – Douglasia 9: 3-4.

Ammal J. 1951. Chromosomes and evolution of garden Philadelphus. – J. Roy. Hort. Soc. 76: 269-275.

Ao CQ. 2008. Pre-zygotic embryological characters of Platycrater arguta, a rare and endangered species endemic to East Asia. – J. Plant Biol. 51: 116-121.

Atkinson BA, Stockey RA, Rothwell GW. 2017. The early phylogenetic diversification of Cornales: permineralized cornalean fruits from the Campanian (Upper Cretaceous) of western North America. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 178: 556-566.

Atkinson BA, Stockey RA, Rothwell GW. 2018. Tracking the initial diversification of asterids: anatomically preserved cornalean fruits from the Early Coniacian (Late Cretaceous) of western North America. – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 179: 21-35.

Avetisian EM. 1975. Palynomorphology of the family Loasaceae. – Palinologija, Izdatel’stvo Akad. Nauk Armjanskoi SSR, Erevan, 1975: 5-18.

Bain JF, Denford KE. 1979. The herbaceous members of the genus Cornus in NW North America. – Bot. Not. 132: 121-129.

Bangham W. 1929. The chromosomes of some species of the genus Philadelphus. – J. Arnold Arbor. 10: 167-169.

Barykina RP, Kapranova NN. 1983. Ontomorphogenesis of some Philadelphus species. – Biol. Nauki 9: 71-76. [In Russian]

Bate-Smith EC. 1978. Astringent tannins of Viburnum and Hydrangea species. – Phytochemistry 17: 267-270.

Bate-Smith EC, Ferguson IK, Hutson K, Jensen SR, Nielsen BJ, Swain T. 1975. Phytochemical interrelationships in the Cornaceae. – Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 3: 79-89.

Bensel CR, Palser BF. 1975. Floral anatomy in the Saxifragaceae sensu lato III. Kirengeshomoideae, Hydrangeoideae, and Escallonioideae. – Amer. J. Bot. 62: 676-687.

Bliss CA, Danielson TJ, Abramovitch RA. 1968. Investigations on the genus Mentzelia I. Mentzeloside, a new iridoid glycoside. – Lloydia 31: 424.

Bloembergen S. 1939. A revision of the genus Alangium. – Bull. Jard. Bot. Buitenzorg, sér. III, 6: 139-235.

Bohm BA, Nicholls KW, Bhat UG. 1985. Flavonoids of the Hydrangeaceae Dumortier. – Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 13: 441-445.

Breuer B, Stuhlfauth T, Fock H, Huber H. 1987. Fatty acids of some Cornaceae, Hydrangeaceae, Aquifoliaceae, Hamamelidaceae and Styracaceae. – Phytochemistry 26: 1441-1445.

Brown DK. 1971. A study of floral morphology in the Loasaceae with emphasis on relationships among the subfamilies. – Ph.D. diss., University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska.

Brown DK, Kaul RB. 1981. Floral structure and mechanism in Loasaceae. – Amer. J. Bot. 68: 361-372.

Brown FBH. 1928. Cornaceae and allies in the Marquesas and neighboring islands. – Bernice P. Bishop Mus. Bull. 52: 1-22.

Brunner F, Fairbrothers DE. 1978. A comparative serological investigation within the Cornales. – Serol. Mus. Bull. 53: 2-5.

Burkett GW. 1932. Anatomical studies within the genus Hydrangea. – Proc. Indiana Acad.Sci. 41: 83-95.

Cannon JFM. 1978a. 92. Alangiaceae. – In: Launert E (ed), Flora Zambesiaca 4, Flora Zambesiaca Managing Committee, London, pp. 633-635.

Cannon JFM. 1978b. 93. Cornaceae. – In: Launert E (ed), Flora Zambesiaca 4, Flora Zambesiaca Managing Committee, London, pp. 635-638.

Cannon R. 1981. Kirengeshoma palmata Saxifragaceae. – Amer. Hort. 60: 32-33.

Carlquist SJ. 1977a. A revision of Grubbiaceae. – J. South Afr. Bot. 43: 115-128.

Carlquist SJ. 1977b. Wood anatomy of Grubbiaceae. – J. South Afr. Bot. 43: 129-144.

Carlquist SJ. 1978. Vegetative anatomy and systematics of Grubbiaceae. – Bot. Not. 131: 117-126.

Carlquist SJ. 1984. Wood anatomy of Loasaceae with relation to systematics, habit, and ecology. – Aliso 10: 583-602.

Carlquist SJ. 1987. Wood anatomy of Plakothira (Loasaceae). – Aliso 11: 563-569.

Carlquist SJ, Schneider EL. 2004. Pit membrane remnants in perforation plates of Hydrangeales with comments on pit membrane remnant occurrence, physiological significance and phylogenetic distribution in dicotyledons. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 146: 41-51.

Chao C. 1954. Comparative pollen morphology of the Cornaceae and allies. – Taiwania 5: 93-106.

Chen LJ. 1988. Comparative embryological study and proposed affinity of Camptotheca, Nyssa and Davidia. – Ph.D. diss., Beijing Institute of Botany, Academia Sinica, Beijing.

Chopra RN, Kaur H. 1965. Some aspects of the embryology of Cornus. – Phytomorphology 15: 353-359.

Clay SN, Nath J. 1971. Cytogenetics of some species of Cornus. – Cytologia 36: 716-730.

Cocucci AA, Sérsic AN. 1997. Evidence of rodent pollination in Cajophora coronata (Loasaceae). – Plant Syst. Evol. 211: 113-128.

Culter JM, Evans WH. 1890. A revision of North American Cornaceae I. – Bot. Gaz. 15: 30-38.

Cusset C. 1973. Révision des Hydrostachyaceae. – Adansonia, sér. II, 13: 75-119.

Dahlgren RMT, Wyk AE van. 1988. Structures and relationships of families endemic to or centered in southern Africa. – Monogr. Syst. Bot. Missouri Bot. Gard. 25: 1-94.

Damtoft S, Jensen SR, Nielsen BJ. 1993. Schismoside, an iridoid glycoside from Schismocarpus matudai. – Phytochemistry 32: 885-889.

Dandy JE. 1926. Notes on Kissenia and the geographical distribution of the Loasaceae. – Kew Bull. 4: 174-180.

Daniels GS. 1970. The floral biology and taxonomy of Mentzelia section Bicuspidaria (Loasaceae). – Ph.D. diss., University of California, Los Angeles, California.

Darlington J. 1934. A monograph of Mentzelia. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 21: 103-227.

Davidson A. 1916. A revision of the western mentzelias. – South. Calif. Acad. Sci. 5: 13-18.

Davis WS, Thompson HJ. 1967. A revision of Petalonyx (Loasaceae) with a consideration of affinities in subfamily Gronovioideae. – Madroño 19: 1-18.

Dermen H. 1932. Cytological studies of Cornus. – J. Arnold Arbor. 13: 410-417.

De Smet Y, Granados Mendoza C, Wanke S, Goetghebeur P, Samain M-S. 2015. Molecular phylogenetics and new (infra)generic classification to alleviate polyphyly in tribe Hydrangeeae (Cornales: Hydrangeaceae). – Taxon 64: 741-753.

Dewilde WJJO, Duyfjes BEE. 2017a. Taxonomy of Alangium section Conostigma (Alangiaceae). – Blumea 62: 29-46.

Dewilde WJJO, Duyfjes BEE 2017b. The species of Alangium section Rhytidandra (Alangiaceae). – Blumea 62: 75-83.

Dhillon M. 1975. Morphology and vascular anatomy of the node and flower of Deutzia staminea R. Brown (Saxifragaceae). – J. Res. Punjab Agric. Univ. 12: 156-160.

Dostert N, Weigend M. 1999. A synopsis of the Nasa triphylla complex (Loasaceae), including some new species and subspecies. – Harvard Pap. Bot. 4: 439-467.

Engler A. 1891. Saxifragaceae. – In: Engler A, Prantl K (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien III(2a), W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 41-93; Nachträge zu III(2a), pp. 180-181.

Engler A. 1895. Hydrostachydaceae africanae. – Engl. Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 20: 136-137.

Engler A. 1930. Saxifragaceae. – In: Engler A, Harms H (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien, 2. Aufl., Bd. 18a, W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 74-226.

Eramijan EM. 1971. Palynological data on the systematics and phylogeny of Cornaceae Dumort. and related families. – In: Kuprianova LA, Yakovlev MS (eds), Pollen morphology of Cucurbitaceae, Thymelaeaceae, Cornaceae, Nauka, Leningrad, pp. 235-273. [In Russian]

Erbar C, Leins P. 2004. Hydrostachyaceae. – In: Kubitzki K (ed), The families and genera of vascular plants VI. Flowering plants. Dicotyledons. Celastrales, Oxalidales, Rosales, Cornales, Ericales, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 216-220.

Erdelska O. 1986. Embryo development in the dogwood Cornus mas. – Phytomorphology 36: 23-28.

Eyde RH. 1963. Morphological and paleobotanical studies of the Nyssaceae I. A survey of the modern species and their fruits. – J. Arnold Arbor. 44: 1-59.

Eyde RH. 1967. The peculiar gynoecial vasculature of Cornaceae and its systematic significance. – Phytomorphology 17: 172-182.

Eyde RH. 1968. Flowers, fruits, and phylogeny of Alangiaceae. – J. Arnold Arbor. 49: 167-192.

Eyde RH. 1972. Pollen of Alangium: toward a more satisfactory synthesis. – Taxon 21: 471-477.

Eyde RH. 1985. The case for monkey-mediated evolution by big-bracted dogwoods. – Arnoldia (Jamaica Plain) 45: 2-9.

Eyde RH. 1987. The case for keeping Cornus in the broad Linnaean sense. – Syst. Bot. 12: 505-518.

Eyde RH. 1988. Comprehending Cornus: puzzles and progress in the systematics of the dogwoods. – Bot. Rev. (Lancaster) 54: 233-351.

Eyde RH. 1991. Nyssa-like fossil pollen: a case for stabilizing nomenclature. – Taxon 40: 75-88.

Eyde RH. 1997. Fossil records and ecology of Nyssa (Cornaceae). – Bot. Rev. (Lancaster) 63: 97-123.

Eyde RH, Barghoorn ES. 1963. Morphological and paleobotanical studies of the Nyssaceae II. The fossil record. – J. Arnold Arbor. 44: 328-376.

Eyde RH, Ferguson K. 1989. The little lost dogwood of Frank Kingdon Ward. – Kew Mag. 6: 74-83.

Eyde RH, Xiang Q. 1990. Fossil mastixioid (Cornaceae) alive in eastern Asia. – Amer. J. Bot. 77: 689-692.

Eyde RH, Bartlett A, Barghoorn ES. 1969. Fossil record of Alangium. – Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 96: 288-314.

Fagerlind F. 1947. Die systematische Stellung der Familie Grubbiaceae. – Svensk Bot. Tidskr. 41: 315-320.

Fairbrothers DE, Johnson MA. 1964. Comparative serological studies within the families Cornaceae (dogwood) and Nyssaceae (sour gum). – In: Leone CA (ed), Taxonomic biochemistry and serology, Ronald Press Co., New York, pp. 305-318.

Fan C, Xiang, Q-Y. 2001. Phylogenetic relationships within Cornus (Cornaceae) based on 26S rDNA sequences. – Amer. J. Bot. 88: 1131-1138.

Fan C, Xiang Q-Y. 2003. Phylogenetic analyses of Cornales based on 26S rRNA and combined 26S rDNA-matK-rbcL sequence data. – Amer. J. Bot. 90: 1357-1372.

Fan C, Purugganan MD, Thomas DT, Wiegmann BM, Xiang Q-Y. 2004: Heterogeneous evolution of the Myc-like anthocyanin regulatory gene and its phylogenetic utility in Cornus L. (Cornaceae). – Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 33: 580-594.

Faure A. 1924. Étude organographique, anatomique et pharmacologique de la famille des Cornacées (Groupe des Cornéales). – Ph.D. diss., Fac. Méd. Pharm., Imp. Centrale du Nord, Lille, France.

Feng C-M, Manchester SR, Xiang Q-Y. 2009. Phylogeny and biogeography of Alangiaceae (Cornales) inferred from DNA sequences, morphology, and fossils. – Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 51: 201-214.

Feng C-M, Xiang Q-Y (J), Franks RG. 2011. Phylogeny-based developmental analyses illuminate evolution of inflorescence architecture in dogwoods (Cornus s.l., Cornaceae). – New Phytol. 191: 850-869.

Ferguson IK. 1966. Notes on the nomenclature of Cornus. – J. Arnold Arbor. 47: 100-105.

Ferguson IK. 1977. Cornaceae Dumort. – In: Nilsson S (ed), World Pollen and Spore Flora 6, Almqvist & Wiksell, Stockholm.

Ferguson IK, Hideux MJ. 1978 [1980]. Some aspects of the pollen morphology and its taxonomic significance in Cornaceae sens. lat. – In: Proceedings of the 4th International Palynological Conference, Lucknow, 1976-1977, 1: 240-249.

Firbairn JW, Lou TC. 1950. A pharmacognostical study of Dichroa febrifuga Lour., a Chinese antimalarial plant. – J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2: 162-177.

Florence J. 1985. Sertum polynesicum I. Plakothira Florence (Loasaceae), genre nouveau des Îles Marquises. – Bull. Mus. Natl. Hist. Nat., sér. IV, sect. C, Adansonia, Botanique, Phytochimie 7: 239-245.

Fosberg FR. 1939. Taxonomy of the Hawaiian genus Broussaisia (Saxifragaceae). – Occas. Pap. Bishop Mus. 15: 49-60.

Franchet MA. 1896. Araliaceae, Cornaceae et Caprifoliaceae novae e flora sinensi. – J. Bot. 10: 301-308.

Freire Fierro A. 2004. 75A. Hydrangeaceae. – In: Harling G, Andersson L (eds), Flora of Ecuador 73, Botanical Institute, Göteborg University, pp. 25-40.

Funamoto T, Nakamura T. 1989. Karyomorphological study on Kirengeshoma palmata Yatabe in Japan (Saxifragaceae). – Chromosome Inf. Serv. 47: 22-23.

Gandolfo MA, Nixon KC, Crepet WL. 1998. Tylerianthus crossmanensis gen. et sp. nov. (aff. Hydrangeaceae) from the Upper Cretaceous of New Jersey. – Amer. J. Bot. 85: 376-386.

Garcia V. 1962a. Embryological studies of the Loasaceae with special reference to the endosperm haustoria. – In: Plant embryology: a symposium, New Delhi, pp. 157-161.

Garcia V. 1962b. Embryological studies in the Loasaceae: development of endosperm in Blumenbachia hieronymi Urb. – Phytomorphology 12: 307-312.

Ge L-P, Lu A-M, Gong C-R. 2007. Ontogeny of the fertile flower in Platycrater arguta (Hydrangeaceae). – Intern. J. Plant Sci. 168: 835-844.

Gelius L. 1967. Studien zur Entwicklungsgeschichte an Blüten der Saxifragales sensu lato mit besonderer Berück-sichtigung des Androeceums. – Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 87: 253-303.

Gervais C, Smith J. 1985. Étude cytotaxonomique des Cornus herbaces de l’île aux Basques (estuaire du Saint-Laurent, Quebec). – Natur. Can. 112: 525-533.

Gilg E. 1894. Loasaceae. – In: Engler A, Prantl K (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien III(6a), W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 100-121.

Gilg E. 1925. Loasaceae. – In: Engler A, Gilg E (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien, 2. Aufl., Bd. 21, W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 522-543.

Goldblatt P. 1978. A contribution to cytology in Cornales. – Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 65: 650-655.

Gong J-Z, Li Q-J, Wang X, Ma Y-P, Zhang X-H, Zhao L, Chang Z-Y, Ronse De Craene L. 2018. Floral morphology and morphogenesis in Camptotheca (Nyssaceae), and its systematic significance. – Ann. Bot. 121: 1411-1425.

Gopinath DM. 1945. A contribution to the embryology of Alangium lamarckii Thw. with a discussion of the systematic position of the family Alangiaceae. – Proc. Indian Acad. Sci., Sect. B, 22: 225-231.

Gorbunov MG. 1970. On the fossil remains of the representatives of the genus Hydrangea in the flora of the locality Compasskiy Bor on the River Tym (west Siberia). – Bot. Žurn. 55: 795-806. [In Russian]

Govindarajalu E. 1961, 1962. The comparative morphology of the Alangiaceae I. The anatomy of the node and internode; II. Foliar histology and vascularization; III. Pubescence; IV. Crystals. – Proc. Natl. Inst. Sci., Sect. B, 27: 375-388 (1961), 28: 100-114, 507-531 (1962).

Govindarajalu E, Swamy BGL. 1956. Petiolar anatomy and subgeneric classification of the genus Alangium. – J. Madras Univ. 26B: 583-588.

Grau J. 1988. Chromosomenzahlen chilenischer Loasaceae. – Mitt. Bot. Staatssamml. München 27: 7-14.

Grau J. 1997. Huidobria, eine isolierte Gattung der Loasaceae aus Chile. – Sendtnera 4: 77-93.

Gregory M. 1998. Hydrangeaceae. – In: Cutler DF, Gregory M (eds), Anatomy of dicotyledons, 2nd ed., vol. 4. Saxifragales, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 87-108.

Greinert M. 1886. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der morphologischen und anatomischen Verhältnisse der Loasaceen, mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Behaarung. – Ph.D. diss., Universität Freiburg, Germany.

Guo Y-L, Pais A, Weakley AS, Xiang Q-Y. 2013. Molecular phylogenetic analysis suggests paraphyly and early diversification of Philadelphus (Hydrangeaceae) in western North America: new insights into affinity with Carpenteria. – J. Syst. Evol. 51: 545-563.

Hamel JL. 1951. Notes préliminaires à l’étude caryologique des Saxifragacées VI. Les chromosomes somatiques des Kirengeshoma palmata Yatabe, Deinanthe coerulea Stapf et Schizophragma integrifolia (Franch) Oliv. – Bull. Mus. Natl. Hist. Nat. Paris, sér. II, 23: 651-654.

Hamel JL. 1953. Contribution à l’étude cytotaxinomique des Saxifragacées. – Rev. Cytol. Biol. Vég. 14: 113-313.

Hao G, Hu C. 1996a. A study of leaf venation of Hydrangeoideae (Hydrangeaceae). – Guihaia 16: 155-160.

Hao G, Hu C. 1996b. A study of pollen morphology of Hydrangeoideae (Hydrangeaceae). – J. Trop. Subtrop. Bot. 4: 26-31.

Hardin JW, Murrell ZE. 1997. Foliar micromorphology of Cornus. – J. Torrey Bot. Soc. 124: 124-139.

Hardin JW, Pilatowski RE. 1981. Atlas of foliar surface features in woody plants III. Hydrangea (Saxifragaceae) of the United States. – J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 97: 29-36.

Harms H. 1898. Cornaceae. – In: Engler A, Prantl K (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien III(8), W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 250-270.

Harms H. 1935. Grubbiaceae. – In: Engler A (†), Harms H (eds), Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien, 2. Aufl., Bd. 16b, W. Engelmann, Leipzig, pp. 46-51.

Hatta H, Honda H, Fisher JB. 1999. Branching principles governing the architecture of Cornus kousa (Cornaceae). – Ann. Bot. 84: 183-193.

He P. 1990. Taxonomy of Deutzia (Hydrangeaceae) from Sichuan, China. – Phytologia 69: 332-339.

He Z-C, Li J-Q, Wang HC. 2004. Karyomorphology of Davidia involucrata and Camptotheca acuminata, with special reference to their systematic positions. – Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 144: 193-198.

Hempel AL. 1995. Molecular systematics of the Loasaceae. – Ph.D. diss., University of Texas, Austin, Texas.

Hempel AL, Reeves PA, Olmstead RG, Jansen RK. 1995. Implications of rbcL sequence data for higher order relationships of the Loasaceae and the anomalous aquatic plant Hydrostachys (Hydrostachyaceae). – Plant Syst. Evol. 194: 25-37.

Henning T, Oliveira S, Schlindwein C, Weigend M. 2015. A new, narrowly endemic species of Blumenbachia (Loasaceae subfam. Loasoideae) from Brazil. – Phytotaxa 236: 47-93.

Hewson HJ. 1984. Alangiaceae. – In: George AS (ed), Flora of Australia 22, Australian Government Publ. Service, Canberra, pp. 11-13.

Hideux M, Ferguson IK. 1976. The stereostructure of the exine and its evolutionary significance in Saxifragaceae sensu lato. – In: Ferguson IK, Muller J (eds), The evolutionary significance of the exine, Linn. Soc. Symposium, No. 1, Academic Press, London and New York, pp. 327-377.