MAGNOLIOPSIDA Brongn.

Brongniart, Enum. Plant. Mus. Paris: xxvi, 95. 12

Aug 1843 [’Magnolineae’]

|

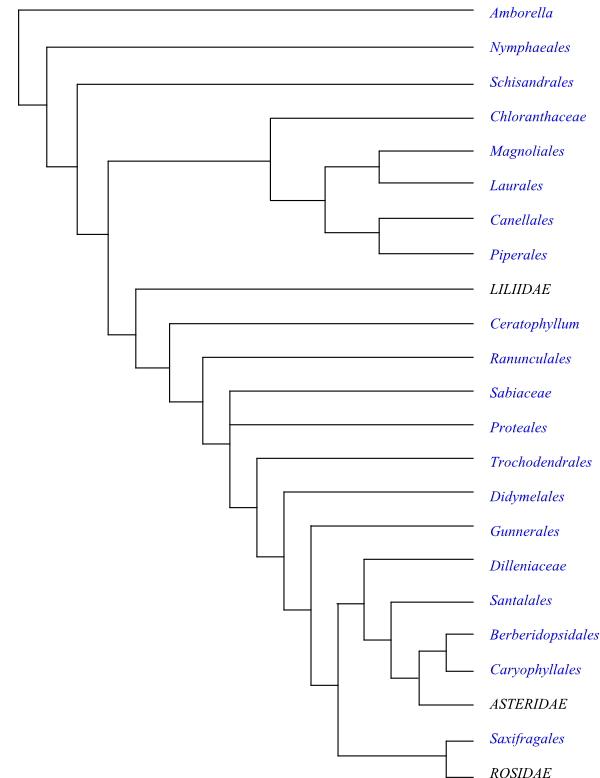

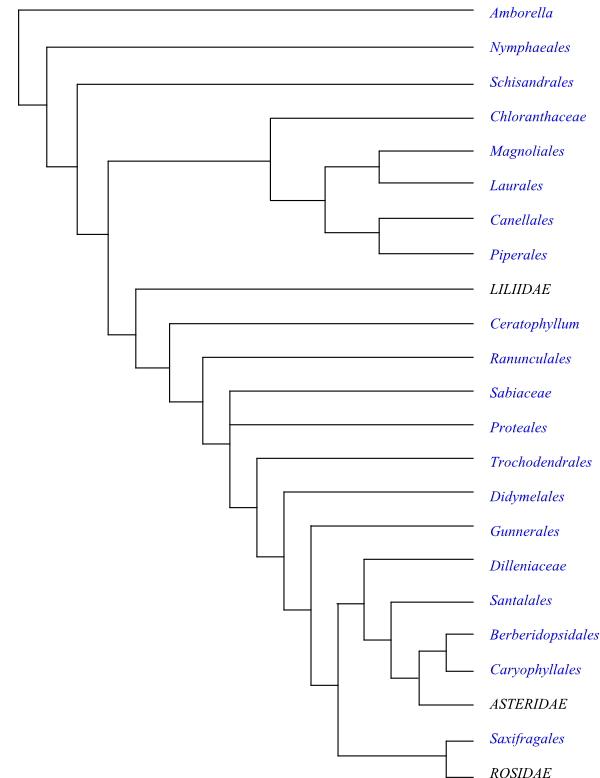

Maximum likelihood (ML) majority-rule consensus

tree of Magnoliopsida (Pan-Angiospermae) based on DNA

sequence data (Soltis & al. 2011, slightly modified).

Amborella, Nymphaeales

and Schisandrales

being successive sister-groups to all other angiosperms had more than

80% bootstrap (BS) support in the 17-gene analysis by Soltis & al.

(2011). The position of Amborella as sister to all other

angiosperms is highly supported by complete plastid genome sequence

analyses (Kim, Yoo & al. 2004; Moore & al. 2007; Soltis &

al. 2011; etc.). The sister-group relationship [Chloranthaceae+Magnoliidae]

had a BS support of 85%. The clades [Magnoliales+Laurales] and

[Canellales+Piperales] each

had a BS support of 100%. The clade comprising Liliidae,

Ceratophyllum and Tricolpatae was supported by 86%,

whereas the support of Ceratophyllum as sister to

Tricolpatae was only 68%. The BS support for Sabiaceae as sister

to the remaining Tricolpatae (a trichotomy in this tree) was

likewise relatively low (59%). Sabiaceae are

sometimes recovered as sister to Proteales, yet

with weak to moderate support (Qiu & al. 2006; Moore & al.

2008; Burleigh & al. 2009; Moore & al. 2011; Soltis & al.

2011). Gunnerales

were sister to the Pentapetalae with a BS support of 99%.

Ranunculales

were as usual sister to the remaining Tricolpatae (BS support

100%). The positions of Didymelales

and Trochodendrales

as successive sister-groups to Gunneridae had a BS support of

98% and 100%, respectively (Moore & al. 2010; Soltis & al.

2011). Gunnerales

were sister to the remaining angiosperms, the Pentapetalae,

with a support of 100%. Superasteridae (Santalales to

Asteridae) and Superrosidae (Saxifragales

and Rosidae) were supported by 87% and 100%, respectively. In

some other analyses Berberidopsidales

were sister to Asteridae, and Caryophyllales

were sister to these two groups. The position of Dilleniaceae

as sister to Superasteridae was supported by 97% in Soltis

& al. (2011). In some other analyses they were recovered as sister

to, i.a., the remaining Pentapetalae, or to the clade

[Superasteridae+Superrosidae] or to

Superrosidae, although with fairly low support (Moore &

al. 2010). The maximum parsimony (MP) consensus tree was largely

identical to the ML tree, although Ceratophyllum was sister to

Liliidae and Dilleniaceae

were sister to Caryophyllales.

– Extant angiosperms began to diversify in the mid-Jurassic, c. 170

Mya, according to unconstrained penalized likelihood analyses (Moore

& al. 2007), and the five major mesangiosperm lineages diversified

fairly rapidly during the earliest Cretaceous. The initial divergence

of these five lineages was dated to 143.8+4.8

Mya, and the divergence of Chloranthus and

Magnoliidae was dated to 140.3+4.8

Mya. The origins of the extant crown groups of Magnoliidae,

Liliidae, and Tricolpatae were dated to branching

points somewhat later in the Cretaceous: 130.1+4.4 Mya for Magnoliidae, 128.9+4.9 Mya for Liliidae, and 124.8+6.3 Mya for Tricolpatae. Divergence times

and standard errors (in parentheses) in Mya for deep-level angiosperm

nodes as estimated by penalized likelihood analyses were as follows:

angiosperms 169.7 (3.46) – Nymphaeales+Illicium+Mesangiospermae

163.5 (2.63) – Illicium+Mesangiospermae 154.8

(2.53) – Mesangiospermae 143.9 (2.67) –

Chloranthus+Magnoliidae 140.4 (2.54) –

Magnoliidae 130.3 (2.20) –

Liliidae+Ceratophyllum+Tricolpatae 143.1

(3.18) – Liliidae 129.1 (2.69) –

Ceratophyllum+Tricolpatae 141.4 (2.97) –

Tricolpatae 124.9 (3.43).

|

Pan-Angiospermae P.

D. Cantino et M. J. Donoghue in Taxon 56, E23. 2007

Habit Bisexual or unisexual,

trees, shrubs, lianas, suffrutices, or perennial, biennial or annual herbs.

Root Main root usually

developing from radicula and usually as tap root with lateral roots (radicula

sometimes ephemeral, all roots of mature plant being adventitious). Root cap

and epidermis usually with common ontogenetic origin. Apical meristem open or

intermediate. Vascular tissue diarch to pentarch. Lateral roots arising

opposite or when diarch immediately adjacent to xylem poles. Phellogen deeply

seated. Trichoblasts (differentiated cells forming root hairs) absent.

Epidermis probably initiated from inner root cap layer.

Stem Shoot apex with

tunica-corpus construction. Tunica two-layered. Phellogen usually superficial

(initiated at or immediately below epidermis; sometimes deeply seated, i.e.

initiated deep in cortex, inside pericycle or in phloem). Vascular bundles

usually arranged in cylinder (annular in cross-section; sometimes in two or

more concentric cylinders or as scattered bundles). Circular bordered pits when

present without margo and torus. Perforation plates (tracheid:tracheid plates)

with primarily scalariform pitting (secondarily simple). Wood fibres

(imperforate tracheary xylem elements) and axial (wood) parenchyma usually

present. Reaction wood with gelatinous fibres. Starch grains simple. Primary

cell walls usually with pectic polysaccharides (mannans sparse). Cytoplasm not

occluding sieve plate pores, containing P proteins. Sieve tube with sieve

plate. Sieve tubes eunucleate (nucleated companion cells, non-nucleated sieve

tube and P proteins developing from common mother cell). Albuminous

Strassburger cells, functionally associated with sieve cells, not developing

from same mother cell. Sieve tube plastids containing only starch grains (S

type), or with protein inclusions as well (P type) (rarely with neither starch

nor protein, S0 type). Nodes usually unilacunar or trilacunar

(sometimes bilacunar or multilacunar) with usually one or three (sometimes two

or more than three) leaf traces. Prophylls (including bracteoles) usually

single or paired.

Leaves Leaf usually with

petiole and lamina (lamina often sessile or leaf only consisting of petiole);

lamina developing from primordial leaf apex. Leaf with acropetal development of

venation. Stipules present or absent. Leaf sheath present (petiole base

sheathing stem) or absent. Secondary venation pinnate, palmate or parallel;

fine venation usually reticulate. Vein endings usually free (with open

venation). Stomata often paracytic, with ends of guard cells level with pore;

outer stomatal ledges producing vestibule. Cuticular wax crystalloids as

parallel oriented platelets (Convallaria type). Leaf margin entire or

serrate (with teeth). Leaf axil usually with bud (axillary bud).

Flower Flower bisexual or

unisexual. Symmetry actinomorphic, bisymmetrical, zygomorphic or asymmetrical.

Pedicel present or absent, usually provided with one or two floral prophylls

(bracteoles). Floral parts spirally arranged or whorled in one or more series.

Floral parts usually present in stable (sometimes unstable) numbers. Perianth

differentiated into sepals and petals or undifferentiated. Tepals usually

centripetally developing, with usually one or three traces, free or more or

less connate, persistent or caducous. Outer tepals (sepals) enclosing or not

enclosing remainder of floral bud. Floral parts when whorled usually trimerous,

tetramerous or pentamerous. Floral nectaries of various origin present or

absent.

Androecium Stamens usually

centripetally (sometimes centrifugally) developing. Each stamen usually

supported by one trace. Stamen usually differentiated into filament and anther

(microsporangia sometimes embedded in distal part of stamen). Filament

band-shaped or terete, usually narrow (sometimes wide and stout). Anther

usually dithecal (microsporangia organized in two groups each with two

sporangia; sometimes monothecal etc.), tetrasporangiate (sometimes

disporangiate or polysporangiate), introrse, latrorse or extrorse.

Microsporangia with at least outer secondary parietal cells dividing. Thecae

usually dehiscing longitudinally (longicidally) by action of hypodermal

endothecium (sometimes poricidally, valvicidally etc.). Endothecial cells

usually elongated at right angles to longitudinal axis of anther. Tapetum

usually secretory (glandular), with binucleate (sometimes uninucleate or

multinucleate) cells (sometimes amoeboid-periplasmodial).

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis usually simultaneous (sometimes successive). Pollen grains

usually mono- or triaperturate (sometimes other numbers), bicellular or

tricellular at dispersal. Male gametophyte tricellular. Tectum continuous,

discontinuous or absent. Infratectal layer usually columellate (sometimes

granular or intermediate). Endexine usually thin, compact and only in apertural

regions lamellate. Male gametangia (antheridia) absent. Male gametes two,

without cell walls, without flagellae. Pollen tube with pectic outer cell wall,

inner wall of callose, and with posterior callose plug and usually moderately

fast growth (between c. 100 µm and c. 600 µm per hour). Siphonogamy

prevailing. Pollen tubes growing inside secretions from stigma and through

stylar canal and ovary locule, or through compitum (non-destructive pollen tube

growing between megasporangial cells), callose being secreted onto cell walls

behind growing pollen tube apex and over entire substigmatic region. Pollen

tube usually penetrating micropylar end of ovule (porogamy) and proceeding into

synergids (sometimes chalazogamy).

Gynoecium Carpels usually

several or numerous, usually more or less connate (sometimes free). Carpels

plicate or ascidiate, postgenitally usually fused (sometimes occluded by

secretion). Carpels usually early closed (rarely delayed, e.g. in many Alismatales,

Cyperales,

Ranunculales,

and Caryophyllales).

Compitum usually present. Carpellary distal-adaxial pollen-receptive part

usually papillate or non-papillate, Dry or Wet (secretory) type stigma

(receptive area sometimes present along free carpellary margins). Pollen grains

deposited on receptive surface. Stigmatic surface also aiding in development of

pollen tubes. Stylar part of gynoecium present or absent (stigma sessile),

often hollow (with central canal).

Ovule Placentation of

different types (axile, parietal, laminar etc.). Ovules usually anatropous,

bitegmic or unitegmic and crassinucellar or tenuinucellar. Micropyle

endostomal, bistomal or exostomal. Each integument one or several cell layers

thick. Inner integument dermal or subdermal in origin. Parietal tissue present

(ovule crassinucellar) or absent (ovule tenuinucellar). Megasporocyte usually

single (archespore sometimes multicellular), hypodermal, present in centre of

ovule. Cytoplasmically dense zone developing between megasporocyte nucleus in

centre of cell and chalazal cell wall, this dense zone persisting through

megasporogenesis. Megasporogenesis resulting in usually linear tetrad.

Functional megaspore without sporopollenin and cuticle and usually chalazal.

Megagametophyte usually monosporic and developing from chalazal cell. Meiosis I

resulting in a dyad of two uninucleate cells divided by transverse cell wall.

Meiosis II yielding a usually linear tetrad of megaspore cells, of which

chalazal cell becomes megaspore and remaining three megaspores degenerating

prior to initiation of megagametogenesis. Large central nucleus of functional

megaspore surrounded by vacuole. Two nuclei migrating to opposite poles of cell

after first mitosis. Two nuclei present at each pole after second mitosis,

nuclei at micropylar pole becoming fusiform. Four nuclei present at each pole

after third mitosis, cytokinesis now taking place. Resulting megagametophyte

8-nucleate and septacellular. Three cells at micropylar end becoming egg

apparatus consisting of usually two synergids and one egg cell. Each synergid

often containing a cuneate filiform apparatus, usually a small number of

plastids and in general with thicker wall than egg cell. Three cells at

chalazal end becoming antipodal cells, usually containing numerous plastids,

and in many cases proliferating (dividing). Nuclei of these cells more or less

fusiform (torpedo-shaped) and each with distinct nucleolus. Remaining two

nuclei, polar nuclei, of seventh cell, central cell, moving to centre of

megagametophyte. Here they are situated in a parietal band of cytoplasm. Female

gametangia (archegonia) absent. Fertilization taking place some time between

one day and one year following pollination. Fertilization double, i.e. one male

gamete fusing with egg cell and second male gamete with central cell containing

two free or fused polar nuclei (polar nuclei fusing in centre of central cell

either immediately prior to or during fertilization process and subsequently

moving into position adjacent to egg cell with its terminal nucleus). Triploid

cell resulting from fertilization of diploid central cell usually developing

into endosperm. Endosperm development cellular, helobial or nuclear. Endosperm

nuclei triploid.

Fruit Fruit developing from

ovary. Additional tissues often contributing to structures surrounding ovary

resulting in pseudofruit. Fruit wall, pericarp, usually consisting of innermost

endocarp, mesocarp outside this, and outer exocarp.

Seeds Seed coat consisting of

one or several layers developed from integument(s). Endosperm sparse to

copious, oily and/or proteinaceous and/or starchy (occasionally absent). Embryo

ab initio cellular. Cotyledons usually two (sometimes one, rarely three or

four), each usually provided with three vascular bundles (when one cotyledon,

then usually with two main vascular bundles). Plumule usually terminal.

Seedling with sympodial growth. Germination usually phanerocotyl (sometimes

cryptocotyl).

Cytology and genes A genes are

found only in angiosperms. A duplication event took place in the ancestor of

angiosperms, which resulted in a D orthologue, usually expressed only in the

ovules, and a C orthologue, only occasionally expressed in ovules, but in

carpels and stamens as well.

Telomeres of Arabidopsis type

(TTTAGGG)n. Entire nuclear genome duplicated. Second duplication of

nuclear genes PEBP resulting in FT-like and

TFL1-like gene families (first duplication leading to two

PEBP gene families, MFT-like and FT/TFL1-like, and

probably coinciding with evolution of seed plants).

Nuclear genes LEAFY and RPB2

present in single copy. knox genes extensively duplicated (A1 to A4).

Nuclear genes AP1/FUL, paleoAP3 and PI (paralogous

B-class genes) present, and possessing “DEAER” motif. Three copies of

nuclear gene PHY (PHYBc(PHYA/PHYC)) and

gene pair SEP3/LOFSEP duplicated (gene PHYA involved

in, i.a., germination and etiolation response of seedling).

Nuclear gene euAP3 in angiosperms

consisting of duplicated copy of gene paleoAP3 with 8 bp insertion

causing a frame-shift mutation. APETALA3 and similar nuclear genes and

PISTILLATA are paralogous B-class genes. B-function MADS-box genes are

extremely important for the floral development.

The exon 5’ in the PI-homologues has

a size of 42 base pairs in the basalmost clades Amborella and Nymphaeales.

Illicium (Schisandrales)

and all younger clades has a deletion of 12 bp in this exon 5’ resulting in a

length of 30 bp.

Plastid gene ndhB extended 21 codons

at 5’ end.

Phytochemistry Lignans,

quercetin and/or kaempferol, O-methyl flavonols, dihydroflavonols,

oleanane (triterpenoid), non-hydrolyzable tannins, tyrosine-derived cyanogenic

compounds, apigenin and/or luteolin present. Lignins often derived from

coniferyl and sinapyl alcohols, containing syringaldehyde (in positive Mäule

reaction, syringyl:guaiacyl ratio higher than 2,0–2,5:1). Hemicelluloses

often present as amyloid (xyloglucans).

Early angiosperm fossils of unknown

affinity (adopted from Friis & al. 2011)

- Fossilized angiosperm leaves occur in Aptian

and younger layers. A peculiar leaf fossil is the Aptian to Albian

Trifurcatia flabellata, which is connected to the fossil genus

Klitzschophyllites. These leaves are thick, circular in outline and

with serrate margins. The venation is flabellate with more than 20 primary and

secondary veins terminating at or between the leaf teeth. Gland-like structures

are present along the leaf margins.

- Small male flowers from the Late Barremian to

the Aptian (Early Cretaceous) of Portugal, with ten to 15 stamens having wide

flat filaments and lateral thecae and trichotomocolpate pollen grains, are in

some way similar to Amborella trichopoda, although the anthers were

extrorse instead of introrse and the pollen surface was verrucate-rugulate.

- The Early Cretaceous (Early to Late Aptian,

the Liaoning Province in northeastern China) probably limnic species of

Archaefructus were herbaceous with multiple times divided leaves and

leaflets. They had naked unisexual terminal reproductive organs usually arising

in pairs, with female and male parts separate on the elongating axis. Bracts

and perianth seem to have been absent. The seed-bearing carpel-like organs

(possibly developing into follicles) were elongated and slightly stipitate and

the stamen-like organs were present two to four together on a common stipe. The

reproductive organ has been interpreted as a single bisexual flower or as an

inflorescence consisting of numerous unisexual units. Archaefructaceae

were recovered as sister to all other angiosperms in a combined morphological

and 3-gene-analysis by Sun & al. (2002). Archaefructaceae comprise

the two species Archaefructus liaoningensis Sun, Dilcher, Ji &

Zhou and A. sinensis Sun, Dilcher, Ji & Nixon.

- Cronquistiflora and

Detrusandra from the Turonian (93,5–89 Mya) in New Jersey had

numerous spiral carpels and other floral parts.

- Caloda delevoryana, from Late Albian

to Early Cenomanian (mid-Cretaceous) strata of the central United States, is

represented by elongate infructescences bearing alternately arranged lateral

branches each ending in a receptacle with numerous free stipitate carpels.

- The floral fossil Carpestella

lacunata, from the Early to Middle Albian (Early Cretaceous) of Virginia,

may have been related to extant basalmost angiosperms. The fossil consists

mainly of a syncarpous gynoecium with 13 carpels covered by spiral scars of

detached perianth and androecium.

- Caspiocarpus paniculiger is

represented by a single shoot from the mid-Albian of Kazakhstan, having

opposite palmately veined leaves and paniculate reproductive axes bearing

follicle-like fruits.

- Cretovarium japonicum from the

Coniacian to Campanian (Late Cretaceous) of Hokkaido (Japan) has perianth-like

structures surrounding a trilocular inferior ovary with axile placentation (two

separate placentae in each locule).

- Hidakanthus shiinae and

Protomonimia kasai-nakajhongii are multicarpellate fruit structures

from the Coniacian to Santonian (Late Cretaceous) of Hokkaido (Japan).

Hidakanthus has c. 55 sessile carpels with oil cells and

Protomonimia c. 170 or stipitate carpels on a concave receptacle. The

seeds of Protomonimia are exotestal.

- Lesqueria elocata represents

elongate infructescences from the Late Albian to Early Cenomanian

(mid-Cretaceous) of Kansas and northern Texas. The gynoecium was apocarpous and

multicarpellate, and bore up to c. 150 helically arranged laminar appendages

and up to c. 250 stalked follicles.

- Xingxueina heilongjiangensis is an

Aptian spicate inflorescence from the Heilongjiang Province in northeastern

China. The proposed floral units are situated in an elongated helix. The

monocolpate pollen grains have a reticulate exine.

- Zlatkocarpus brnikensis and Z.

pragensis resemble the Chloranthaceae.

They have spicate inflorescences with helically arranged floral units

containing a single carpel subtended by an adnate bract and probably developed

into a berry with resin bodies (possibly ethereal oil cells) in the

pericarp.

- A number of flowers have been described from

Cretaceous strata in New Jersey and Portugal. Mabelia (Turonian, Late

Cretaceous) and Nuhliantha (Late Santonian, Late Cretaceous) were

trimerous and unisexual, with six tepals and three extrorse stamens containing

monocolpate (monosulcate) or trichotomocolpate pollen grains. With the

exception of a pistillodium in Nuhliantha no female organs are known.

The floral morphology suggests a monocotyledonous affinity.

Microvictoria (Turonian) consists of bisexual pedicellate flowers

bearing numerous tepals (or bracts?), flattened staminodia and stamens and

carpels. They are similar to flowers in Nymphaeaceae,

although this relationship may be questioned.

- Numerous fossilized fruits and seeds occur in

Cretaceous layers. The Early Cretaceous Anacostia represents small

single-seeded berries with exotestal anatropous seeds. Trichotomocolpate pollen

grains with reticulate tectum are often associated with these fruits. The

flowers seem to have been apocarpous with several or many carpels.

Couperites likewise comprises single-seeded berries with exotestal

anatropous seeds, often found together with monocolpate pollen grains with

reticulate sexine similar to the Clavatipollenites pollen type.

- Angiosperm pollen grains are frequent in

Cretaceous beds. The Afropollis form genus includes spheroidal,

acolumellate coarsely reticulate grains, usually with a granular infratectum.

They may be zonacolpate, monocolpate or inaperturate and either isopolar or

heteropolar. Afropollis occurs in Early Cretaceous layers from the

Barremian to the Cenomanian. The angiospermous origin of Afropollis

has been questioned, i.a. due to the presence of a thick laminar endexine

unknown among extant flowering plants. The similar Schrankipollis form

genus from the Early Cretacous represents zonacolpate, loosely reticulate

pollen grains with columellate infratectum.

- Clavatipollenites comprises

monocolpate pollen grains with a reticulate exine, finely verrucate colpus

membrane and indistinct colpus margins. Many Clavatipollenites grains

have been assigned to Chloranthaceae,

and to Ascarina in particular, although the form genus

Clavatipollenites certainly represents several different early

angiosperm clades.

- Retimonocolpites dividuus is an

Early Cenomanian monocolpate pollen with a reticulate exine and an aperture

encircling most of the grain. Brenneripollis represents monocolpate

pollen grains with irregularly reticulate exine and columellate infratectum,

whereas the similar Pennipollis has acolumellate infratectum.

- Liliacidites is monocolpate or

trichotomocolpate and has a graded reticulum with the small lumina concentrated

in the equatorial area. This Early Cretaceous to Early Cenozoic type resembles

pollen grains of extant monocotyledons. Similipollis, also with

possible monocotyledonous affinities, has the small lumina of the reticulum

concentrated in the polar area.

- The Barremian to Cenomanian

Stellatopollis comprises monocolpate pollen grains with columellate

infratectum and reticulate exine beset with clavate supratectal elements which

are borne in a stellate pattern. The Albian Transitoripollis pollen

type is monocolpate and has continuous verrucate to microechinate tectum and

granular infratectum. The Barremian to Aptian Tucanopollis is similar

to Transitoripollis, but the colpus is sometimes nearly circular in

outline. The large Lethomasites pollen type is also monocolpate and

tectate with granular infratectum, although the tectum is perforate.

Systematics The main clades of

flowering plants are briefly presented below. The potential synapomorphies are

mainly adopted from Peter F. Stevens, “The Angiosperm Phylogeny Website”,

version 9 (June 2008, updated in July 2012). More comprehensive descriptions

are given for Magnoliidae (the magnolids), Liliidae (the

monocots), Asteridae (the asterids), and Rosidae (the

rosids).

Nymphaeidae J. W.

Walker ex Takht., Divers. Classif. Fl. Pl.: 74. 24 Apr 1997

[Nymphaeales+[Schisandrales+[[Chloranthaceae+Magnoliidae]+[Liliidae+[Ceratophyllum+Tricolpatae]]]]]

Potential synapomorphies: Vessels

present in wood (xylem). Vessel elements with elongated scalariform perforation

plates. Wood fibres (imperforate tracheary xylem elements) present. Axial

parenchyma diffuse or diffuse-in-aggregates. Pollen grains monosulcate

(anasulcate). Exine tectate, columellate, reticulate to perforate. “DEAER”

motif of AP3 and PI genes absent (lost). –

Nymphaeidae comprise all extant flowering plants except Amborella

trichopoda. Wood characters in general are extremely variable and very

much depend on the environmental conditions. The wood anatomical variation is

also, naturally, correlated with size, age and life style of the plant. Hence,

the presence of different types of perforation plates, pits, imperforate

tracheary xylem elements, wood (axial) parenchyma, and wood rays only

exceptionally present features useful at taxonomically higher levels.

Illiciidae C. Y. Wu in

Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 40: 291. 2002

[Schisandrales+[[Chloranthaceae+Magnoliidae]+[Liliidae+[Ceratophyllum+Tricolpatae]]]]

Potential synapomorphies: Vessels

present in stem xylem. Ethereal oils in spherical idioblasts (oil cells, making

leaves and tepals pellucid-punctate). Tension wood absent. Anther wall with

dividing outer secondary parietal cell layer. Sexine reticulate. Infratectal

layer columellate. Carpels plicate, sealed by postgenital fusion of their

margins. Nucellar cap present. Deletion comprising 12 bp (representing four

amino acids) in exon 5’ of nuclear gene PI. – Illiciidae include

all angiosperms except Amborella and Nymphaeales.

Mesangiospermae M. J.

Donoghue, J. A. Doyle & P. D. Cantino in Taxon 56, E23. Aug 2007

[[Chloranthaceae+Magnoliidae]+[Liliidae+[Ceratophyllum+Tricolpatae]]]

Potential synapomorphies: Endomycorrhiza

vesicular-arbuscular. Outer epidermal walls of root elongation zone provided

with cellulose fibrils transversely orientated in relation to root axis.

Perianth trimerous. Tepals whorled, trimerous. Stamens whorled. Megagametophyte

bipolar, septacellular, octanucleate. Antipodal cells persistent. Endosperm

triploid. Benzylisoquinoline alkaloids and polyacetate-derived anthraquinones

present. – Mesangiospermae embrace flowering plants other than the

ANITA grade (i.e. Amborella, Nymphaeales and

Schisandrales).

It is questionable whether whorled floral parts is a synapomorphy at this

level. Both spiral and whorled tepals, stamens and carpels are frequent in

Magnoliidae.

[Chloranthaceae+[[Magnoliales+Laurales]+[Canellales+Piperales]]]

Potential synapomorphies: Seed coat

endotestal. Sesquiterpenes present.

Magnoliidae Novák ex

Takht., Sist. Filog. Cvetk. Rast.: 51. 4 Feb 1967 (magnolids)

[[Magnoliales+Laurales]+[Canellales+Piperales]]

Potential synapomorphies: Vessel

elements solitary and in radial multiples. Sieve tube plastids often containing

polygonal protein crystals. Leaf margin entire. Stamens numerous, spirally

arranged. Anthers extrorse. Hypostase present. Nucellar cap present. Antipodal

cells ephemeral. Raphal bundle branches present at chalaza. Galbacin and

verguensin (lignans) present. Licarin (neolignan) sometimes present. Asarone

(phenylpropane)?

Habit Usually woody (in Piperales usually

herbaceous). Often aromatic.

Vegetative anatomy Medulla

septate, with sclerenchymatous diaphragmata. Primary stem with eustele or

(pseudo)siphonostele (sometimes atactostele), with separate (sometimes

scattered) vascular bundles or with continuous vascular cylinder (rarely with

several concentric cylinders). Secondary lateral growth rarely anomalous or

absent (Piperales). Wood elements

(and cambium) sometimes storied. Vessel elements with usually scalariform or

simple (sometimes opposite or reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits

alternate, scalariform or opposite, simple or bordered pits; vessel elements

sometimes absent and replaced by tracheids. Vestured pits sometimes present.

Imperforate tracheary xylem elements tracheids, fibre tracheids or libriform

fibres with simple or bordered pits, septate or non-septate, or absent.

Secondary phloem often stratified. Sieve tube plastids usually Psc type

(sometimes Ss, S0, Pcs, Psf, Pcsf, P2c, or Pc type). Secretory

cavities with resins present or absent. Wood rays sometimes with oil cells or

crystals. Idioblasts with ethereal oils often present at least in parenchyma.

Sclereids often present. Mucilage ducts sometimes present. Silica bodies

sometimes present. Calciumcarbonate as prismatic, rhomboidal or acicular

crystals, styloids, druses or crystal sand sometimes present.

Trichomes Hairs unicellular or

multicellular, usually uniseriate, simple or branched (stellate, dendritic,

furcate, peltate, lepidote, candelabra-shaped, T-shaped or fimbriate), or

absent; glandular hairs usually absent (pearl glands occasionally present).

Leaves Usually alternate

(sometimes opposite, rarely verticillate), simple, usually entire (rarely lobed

or scale-like), with conduplicate, supervolute, involute, convolute, curved or

flate ptyxis. Stipules usually absent (sometimes intrapetiolar or ocreate and

enclosing young leaf); leaf sheath absent (petiole rarely sheathing). Venation

usually pinnate, eucraspedodromous or brochidodromous (rarely campylodromous,

palmate, acrodromous or actinodromous, triplinerved or pedate). Stomata usually

paracytic (sometimes tetracytic, rarely anomocytic, actinocytic, cyclocytic or

helicocytic). Cuticular wax crystalloids as platelets (sometimes parallel),

rodlets (often transversely ridged Aristolochia type crystalloids) or

tubuli (sometimes as clustered tubuli of Berberis type), chemically

characterized usually by presence of palmitone (hentriacontan-16-one) and

absence of nonacosan-10-ol (nonacosan-10-ol present in Canellales). Lamina

often gland-dotted. Domatia sometimes present in abaxial vein axils. Mesophyll

and epidermis usually with idioblasts (secretory cavities) containing ethereal

oils (sometimes calciumoxalate crystals, resin or mucilage) or sclereids,

sometimes with calciumoxalate druses. Sclerenchymatous idioblasts with branched

sclereids of various kinds (also asterosclereids) or fibres often present.

Silica bodies sometimes present. Leaf margin usually entire (sometimes serrate

with monimioid teeth).

Inflorescence Cymose panicle,

umbellate, corymb, rhyrse, cyme or fasciculate (sometimes spadix; rarely

capitate, spicate or raceme), or solitary. Floral prophyll (bracteole) often

single, median, adaxial (sometimes absent).

Flowers Usually actinomorphic

(in Piperales

usually zygomorphic). Usually hypogyny (rarely half epigyny or epigyny),

sometimes with urceolate, campanulate, cupular or infundibuliform receptacle

surrounding floral parts. Tepals (two or) three (or 2+2) or 3+3(+3) (sometimes

2+2+2 or 4+4, rarely to more than 50), with valvate (usually outer) or

imbricate (outer or inner; rarely decussate) aestivation, spiral or whorled,

sepaloid (usually outer) or petaloid (usually inner), usually free or connate

only at base (sometimes intirely connate); tepals sometimes absent. Nectary

usually absent (sometimes with nectariferous disc, staminal nectariferous

glands or adaxial nectaries inside perianth tube). Disc usually absent.

Androecium Stamens (one or)

two to c. 20 to more than 200, laminar (foliaceous), spiral or whorled, not

differentiated into filament and anther, with separate microsporangia embedded

in distal part (adaxially, laterally, abaxially or apically), or differentiated

into filament and anther. Filaments when present usually free from each other

(sometimes partially or entirely connate; occasionally adnate to pistil into

synandrium or gynostemium), usually free from tepals, sometimes with basal

nectariferous glands. Anthers when present usually basifixed, non-versatile,

usually free (rarely adnate to style), usually tetrasporangiate (sometimes

disporangiate), sometimes with transversely septate thecae, extrorse, latrorse

or introrse, longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits) or valvicidal

(dehiscing by valves), sometimes connate into synandrium; or microsporangia

four, usually adaxial or lateral (sometimes abaxial), usually introrse or

latrorse (sometimes extrorse), longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits) or

valvicidal (dehiscing by valves). Tapetum secretory or amoeboid-periplasmodial.

Staminodia extrastaminal, intrastaminal, or absent.

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis simultaneous, successive or intermediate. Pollen grains

usually monosulc(ul)ate (anasulc[ul]ate), monoporate or inaperturate (sometimes

di- or trisulc[ul]ate, trichotomosulcate, polyporate, etc.), boat-shaped,

usually shed as monads, usually bicellular at dispersal. Exine with granular,

columellate or intermediary infratectum.

Gynoecium Carpels usually ten

to more than 50 (sometimes one or few), spiral or whorled, free or more or less

connate (sometimes paracarpous); carpel plicate to conduplicate (sometimes

basally ascidiate and not differentiated into ovary and style), usually

postgenitally incompletely or entirely occluded by fusion and/or secretion,

with secretory canal, often open and filled by secretions, or without canal.

Carpels often not differentiated into ovary, style and stigma. Ovary usually

superior (sometimes inferior, rarely semi-inferior), unilocular to 20-locular

(or more). Stylodium or style single, terminal, usually simple (occasionally

lobate), or stylodia lateral to gynobasic, or absent (pollen tube transmitting

tissue well developed). Stigma capitate or lobate, terminal or decurrent,

papillate or non-papillate, Dry or Wet type. Nectar sometimes secreted from

exposed carpel surfaces. Pistillodium usually absent (male flowers sometimes

with pistillodium).

Ovules Placentation parietal,

laminar, marginal, submarginal, apical, subapical, basal, subbasal, lateral or

axile. Ovules (one or) two to more than 100 per carpel (or one per ovary),

usually anatropous (sometimes hemianatropous, orthotropous, hemiorthotropous or

campylotropous), ascending, horizontal or pendulous, apotropous, usually

bitegmic (sometimes unitegmic, rarely tritegmic), usually crassinucellar

(sometimes tenuinucellar). Micropyle endostomal or bistomal (rarely exostomal),

sometimes Z-shaped (zig-zag). Funicular obturator sometimes present. Archespore

usually unicellular (rarely multicellular). Nucellar cap present or absent.

Nucellar beak present or absent. Megagametophyte usually monosporic,

Polygonum type (sometimes tetrasporic, Fritillaria or

Peperomia type, etc.). Synergids usually with filiform apparatus.

Antipodal cells ephemeral or persistent, sometimes proliferating. Endosperm

development usually cellular (sometimes nuclear). Chalazal or micropylar

endosperm haustoria sometimes present. Embryogenesis onagrad, asterad, piperad,

or irregular.

Fruit A usually fleshy

(sometimes leathery or more or less woody), dehiscent or indehiscent,

apocarpous follicular fruit or a multifolliculus, or a dry or fleshy syncarp, a

loculicidal (and occasionally septicidal) capsule, or a drupe (sometimes a

single-seeded berry or an assemblage of achenes, berries, drupelets, dry

follicles, samaras, etc.).

Seeds Perisperm usually not

developed (in Piperales usually

copious, starchy). Endosperm copious (to scarce), oily (occasionally also with

compound starch grains), or absent. Embryo straight or slightly curved, more or

less differentiated or undifferentiated, without chlorophyll. Cotyledons

usually two.

DNA Deletion of 30 bp

(corresponding to 10 amino acids) present in PI-derived motif in

nuclear gene AP3 in most Magnoliales. Gene

PI duplicated in Laurales. Intergenic

inversion of c. 200 bp present in plastid inverted repeat in Laurales. Nuclear gene

PHYE lost in Piperales.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin, etc.), 5-O-methylflavonols, flavones,

flavanonols, diarylpropanes, catechins, cyanidin, monoterpenes, diterpenes

(kauranes, clerodanes etc.), triterpenoids (tetracyclic etc.), oleanolic acid

derivatives, sesquiterpenes, drimane sesquiterpenoids, sesquiterpene lactones,

allyl- and propenylphenols, oxyphenols and other aromatic substances,

phenylpropanes, caffeic acid, tannins, proanthocyanidins, aporphine alkaloids

(aporphines, oxoaporphines, etc.), aporphine derivatives, benzylisoquinoline

and other isoquinoline alkaloids, protoberberine alkaloids,

C-methylated alkaloids, indole alkaloids, polyketide alkaloids (e.g.

hallucinogenic pyridine alkaloids), quercetin glycosides, cyanogenic glycosides

(dhurrin, triglochinin etc.), α-pyrones, myristicin,

N-(cinnamoyl)-tryptamines, lignans (austrobailignan, veraguensin,

dihydrocubebin), neolignans (aryltetralin, diaryltetrahydrofurans, etc.),

lignoids, ethereal oils, phenanthrenes, aristolochic acids, polyketides,

nitrophenyl ethan, germacrane-like compounds, myo-inisitol,

syringaresinol, pinitol, kadsurin A, galbacin, licarin A, naphthoquinones,

cinnamoylamides, arbutin, asarone, and amides present. Ellagic acid, gallo- and

ellagitannins not found.

Fossils Examples of early

fossils not assigned to any particular magnoliid clade are as follows.

- Araripia florifera, from Upper

Aptian to Lower Albian of Brazil, is represented by a flowering shoot with

decussate trilobate leaves. The tepals and bracts are spirally inserted on a

cupular receptacle. It has not been possible to assign this fossil to a

particular clade of the Magnoliidae.

- Detrusandra mystagoga, from the

Turonian (Late Cretaceous) of New Jersey, is another uplaced magnoliid fossil

comprising pedicellate flowers with cup-shaped receptacle, on which bracts and

tepals are spirally inserted. The numerous stamens are situated on the inner

upper part of the receptacle. The four microsporangia are adaxial on each

stamen. The pollen grains are monocolpate with a reticulate exine. The five

carpels are plicate and free and the stigmas are bilobate. Ovules are numerous

and arranged in two ventral rows.

- Cronquistiflora sayrevillensis is a

Turonian floral fossil from New Jersey. It resembles the above two fossils,

having spirally arranged bracts and tepals, but the receptacular cup is

shallow. The numerous free carpels are spirally inserted and terminating in a

peltate stigma. The ovules are interpreted as orthotropous, bitegmic and with

an endostomal micropyle.

- Canrightia resinifera, from the

Aptian to Early Albian of Portugal, comprises fossilized flowers, fruits and

seeds. The tepals are arranged in one whorl and connate, forming a hypanthium.

The pollen grains are monocolpate with a reticulate exine and columellate

infratectum. The two to five carpels are unilocular, connate and adnate to the

tepals. The single ovule is orthotropous, endotestal-endotegmic and has a

well-developed endothelium (also present in the extant Lactoris

fernandeziana). Resin bodies are frequent on the ovary walls, indicating

the presence of oil cells. The fruit was probably a berry.

Systematics Cuticular wax

crystalloids as transversely ridged rodlets (Aristolochia type) are of

high systematic significance characterizing Magnoliales, Laurales and Piperales. Sporadically,

they also occur in various other taxa. Chemical analyses show that transversely

ridged rodlets clearly differ in their composition. Waxes of one group are

characterized by ketones, whereas a second group completely lacks ketones and

is dominated by alkanes. Hentriacontan-16-one (palmitone) was found to be

characteristic for transversely ridged rodlets in Aristolochia,

Laurus, and Paeonia. Transversely ridged rodlets or related

crystals grow from total waxes of all species but never crystallize from

individual compounds such as alkanes or palmitone. Transversely ridged crystals

are formed by self-assembly based on a slow crystallization process and the

presence of additives.

[Magnoliales+Laurales]

Potential synapomorphies: Cuticular wax

crystalloids as annularly ridged rodlets; main wax palmitol. Stamens whorled.

Pollen grains with lamellate endexine. Carpel cross-zone initiated late.

Placentation basal. Ovules one (or two) per carpel, orthotropous, apotropous.

Fruitlets single-seeded.

[Canellales+Piperales]

Potential synapomorphies: Nodes 3:3.

Carpels whorled. Flavonols and aporphine alkaloids present.

[Liliidae+[Ceratophyllum+Tricolpatae]]

Potential synapomorphies: Tepals present

in two whorls (secondarily one whorl). Stamens present in two whorls

(secondarily one whorl), outer whorl antesepalous, inner whorl antepetalous.

Liliidae J. H. Schaffner in Ohio Naturalist 11: 413.

Dec 1911 (monocotyledons)

Habit Usually perennial herbs

(sometimes secondarily woody). Growth basically sympodial (sometimes

monopodial). Prophylls usually single, adaxial. Often with bulb or corm rich in

polysaccharides. Usually without idioblasts containing ethereal oils etc.

Root Ectomycorrhiza usually

absent (Arum type or Paris type arbuscular mycorrhiza

occasionally present). Radicula usually ephemeral, early withering and replaced

by adventitious roots from stem (or sometimes from hypocotyl). Root cap and

root epidermis of different ontogenetic origin. Root epidermis developing from

outer cortical layer. Inner epidermis absent. Tunica two-layered. Single- or

multi-layered velamen often present. Trichoblast present in atrichoblast or

trichoblast cell pair further from apical meristem. Trichoblasts (small densely

staining cells giving rise to root hairs) present in vertical files with small

proximal cell (near root apex) producing root hairs, or hypodermal cells

(particularly those with velamen) sometimes dimorphic (root hairs pushing up

through overlying cells). Phellogen usually absent (rarely superficial;

phellogen initially developing immediately inside exodermis). Vascular root

tissue oligarch to polyarch, usually medullated. Lateral roots arising opposite

phloem poles. Endodermal cells with U-shaped wall thickenings. Secondary growth

usually absent; anomalous when present. Vessels present only in roots. Vessel

elements with scalariform or simple perforation plates. Tracheids absent.

Stem Distinct bark and medulla

usually absent. Primary thickening meristem at least usually absent. Vascular

system usually consisting of numerous separate scattered bundles (atactostele),

often amphivasal, closed (sometimes consisting of one or two or more concentric

cylinders of bundles). Interfascicular (vascular) cambium usually not

developing (vestigial cambium occasionally present; vascular bundles sometimes

with weakly developed cambial layer). Thickening of main axis sometimes taking

place by division and enlargement of ground parenchyma cells (diffuse secondary

growth) or by special type of cambium arising in parenchyma outside primary

vascular system. Secondary lateral growth usually absent (anomalous when

present). Amphivasal vascular bundles usually present. Vessel elements usually

absent in stem and leaves; when present with usually scalariform (sometimes

simple, rarely reticulate) perforation plates; lateral pits scalariform or

alternate, simple or bordered pits. Imperforate tracheary xylem elements

tracheids. Phloem parenchyma absent. Vascular bundles with late developing

thick-walled sieve tubes without companion-cells. Sieve tube plastids usually

P2c or P2cf types (sometimes P2cs or P2cfs type, rarely Ss type). Laticifers

and latex sometimes present. Schizogenous ducts and cavities with resins and

oils sometimes present. Secretory (often lysigenous) mucilage cavities and

ducts often present. Tanniniferous idioblasts sometimes present. Idioblasts

with suberised cell walls and containing aromatic oils and resins sometimes

present. Silica bodies present or absent (special cells, isodiametric stegmata

connected to fibres, with cap-shaped, druse-like, stellate, conical,

boat-shaped or spherical silica bodies, sometimes present). Mucilage cells,

ducts and chambers present, often with calciumoxalate as raphides,

pseudo-raphides, styloids, crystal sand, or rhomboidal, cuboid or acicular

crystals. Epidermal cells often with crystals.

Trichomes Hairs usually absent

(sometimes unicellular or multicellular, uniseriate or multiseriate, simple or

branched, T-shaped, stellate, peltate or lepidote, rarely prickly or

dendritic); microhairs sometimes present; glandular hairs usually absent

(multicellular glandular hairs or tricellular glandular microhairs rarely

present).

Leaves Usually alternate

(often tristichous; rarely opposite or verticillate), usually simple and entire

(sometimes compound and/or lobed), often linear, usually bifacial, often

subulate (sometimes equitant), with revolute, supervolute, involute, convolute,

conduplicate, plicate, explicative, adplicate, curved or flat ptyxis, not

differentiated into petiole and lamina (sometimes differentiated into

pseudopetiole and pseudolamina, ptyxis then referring to pseudolamina); when

seemingly present, then not homologous to petiole and lamina in other

angiosperms (true lamina absent). Majority of leaf usually developing from

hypophyll (pseudolamina developing from leaf base zone). Vorläuferspitze

(precursor tip, abaxial unifacial conical or cylindrical protrusion at apex of

mature leaf, representing upper part of leaf) often present. Stipules usually

absent (rarely present as axillary scales inside leaf sheath); leaf sheath open

or closed, often well developed, or absent (rarely with axillary intravaginal

scales/colleters, squamulae intravaginales, in Alismatales).

Ligule(s) (developing from adaxial intercalary meristems in transition zone

between hypophyll and hyperphyll) sometimes present. Venation parallelodromous

or pinnate-parallelodromous (rarely acrodromous, pedate, curvipalmate,

campylodromous, reticulodromous, actinodromous or camptodromous), acropetally

and basipetally developing from base, converging towards apex (closed at apex),

or secondary pseudopinnate or pseudopalmate types; intermediate and other veins

basipetal from apex; vein endings not free. Imperforate tracheary xylem

elements tracheids. Stomata paracytic (in lines, parallel to long axis of

leaf), brachyparacytic (cell divisions oblique), tetracytic, anomocytic, or

tricytic (sometimes cyclocytic, hexacytic or polycytic); neighbouring cells

with oblique or non-oblique divisions. Cuticular wax crystalloids as parallel

platelets (Convallaria type), as longitudinally aggregated rodlets

(Strelitzia type, chemically dominated by wax esters) or as unordered

platelets, rodlets or filiform reticulate processes, or absent. Dimorphic

hypodermal cells sometimes present. Epidermis often with bulliform cells or

with idioblasts containing silica bodies. Mesophyll often with sclerenchymatous

idioblasts, or with mucilaginous idioblasts containing calciumoxalate raphides,

druses, prismatic or rhomboidal crystals, styloids, or crystal sand (sometimes

with idioblasts containing ethereal oils). Schizogenous laticiferous cavities

sometimes present. Tanniniferous cells sometimes abundant. Leaf margin usually

entire (sometimes serrate or spinose-serrate). Leaf teeth non-glandular.

Inflorescence Simple or

compound, cymose pseudumbel or pseudoraceme, spicate or capitate, panicle,

fascicle, corymb, thyrsoid or spadix, often compound and consisting of

bostrychoid or helicoid monochasial partial inflorescences, or raceme or spike,

sometimes subtended by one or several spathae (enlarged bract usually

surrounding spadix); or flowers solitary. Floral prophylls (bracteoles) usually

single, usually adaxial, bicarinate (rarely lateral, pairwise or absent;

axillary flowers sometimes possibly representing reduced lateral inflorescence

branches).

Flowers Actinomorphic or

zygomorphic, often with median outer tepal adaxial (rarely asymmetrical).

Flowers usually pentacyclic and trimerous. Hypanthium rarely present. Hypogyny

or epigyny (rarely half epigyny). Usually trimerous (rarely dimerous,

tetramerous or pentamerous), usually pentacyclic. Perianth pseudomonocyclic

(each providing sector for perianth tube when present). Tepals

(2–)3(–7)+(2–)3(–7), in two whorls, often similar, with tepals of

successive whorls alternating, with usually open (sometimes imbricate or

valvate; rarely contorted, conduplicate, induplicate, etc.) aestivation, all

sepaloid or petaloid, or outer tepals sepaloid and inner tepals petaloid, free

or more or less connate into infundibuliform, tubular or urceolate perianth, or

absent (tepals sometimes membranous or chartaceous, sometimes modified into

scales, bristles or hairs); median outer tepal usually abaxial (rarely

adaxial); each tepal provided with three leaf traces. Nectaries as septal

nectaries, usually infralocular, or androecial nectaries (rarely tepal

nectaries), or absent. Disc usually absent (nectariferous disc occasionally

present).

Androecium Stamens

(2–)3(–6)+(2–)3(–6) (sometimes one or three, rarely two, five, 6+3, 6+4

or up to more than 1.000), usually as many as tepals, usually antesepalous

(sometimes antepetalous), whorled. Staminal primordia often associated and/or

stamens vascularized from tepal trace. Anther and filament sharply

distinguished. Filaments free from each other or more or less connate (rarely

connate into synandrium), free from or adnate to tepals (epitepalous; rarely to

style). Anthers usually dorsifixed, basifixed or subbasifixed (sometimes

centrifixed), versatile or non-versatile, usually tetrasporangiate (rarely

disporangiate or trisporangiate), introrse, latrorse or extrorse, usually

longicidal (dehiscing by longitudinal slits; sometimes poricidal, dehiscing by

one or two apical or subapical pores, or transverse slits). Endothecium

developing from outer secondary parietal cell layer; inner secondary parietal

cell layer dividing. Tapetum usually secretory (sometimes

amoeboid-periplasmodial), with uninucleate to quadrinucleate cells. Staminodia

present (rarely petaloid) or absent (female flowers often with staminodia).

Pollen grains

Microsporogenesis usually successive (sometimes simultaneous); tetrads usually

tetragonal. Pollen grains usually monosulcate (monocolpate; sometimes

monosulcoidate, disulcate, trichotomosulcate, mono- to polyporate,

spiraperturate, inaperturate, etc.), usually shed as monads (rarely dyads,

tetrads, polyads or cryptotetrads), usually bicellular (sometimes tricellular)

at dispersal. Exine usually with columellate (sometimes granular) infratectum.

Endexine usually absent. Callose plugs of pollen tube usually irregularly

spaced and incomplete.

Gynoecium Pistil composed of

(one to) three (to more than 100) usually more or less connate (eusyncarpous or

paracarpous; sometimes secondarily free), usually whorled (rarely seemingly

spiral), antesepalous carpels; median carpel usually abaxial; carpel plicate or

conduplicate; fusion congenital intercarpellary and/or postgenital; carpel

ascidiate to plicate or intermediate, seemingly occluded by secretion. Ovary

superior or inferior (rarely semi-inferior), (unilocular to) trilocular or

multilocular. Style single, simple, with stylar canal (hollow), or stylodia

terminal, lateral (rarely gynobasic), or absent. Stigma capitate, punctate,

peltate or lobate (sometimes infundibuliform, copular, etc.), or stigmas

linear, papillate or non-papillate, Dry or Wet type. Pistillodium usually

absent (male flowers sometimes with pistillodium).

Ovules Placentation axile,

parietal, basal, subbasal or apical (rarely laminar or marginal). Ovules one to

more than 100 per carpel (rarely hundreds to tens of thousands or more),

anatropous or campylotropous (sometimes semicampylotropous, hemianatropous,

amphitropous, orthotropous, pleurotropous, plagiotropous, etc.), ascending,

horizontal or pendulous, apotropous or epitropous, usually bitegmic (sometimes

unitegmic, rarely ategmic), crassinucellar or tenuinucellar (sometimes

pseudocrassinucellar or pseudotenuinucellar). Micropyle endostomal or bistomal

(sometimes exostomal). Funicular obturator sometimes present. Parietal cell

formed from archesporial cell (parietal tissue usually one cell layer thick) or

absent. Periclinal cell divisions sometimes taking place in megasporangial

tissue (parietal cell then not formed). Nucellar cap sometimes formed by

periclinal divisions of megasporangial epidermis. Epidermal cells of

megasporangium sometimes forming ‘nucellar pad’. Megagametophyte usually

monosporic, Polygonum type (occasionally Oenothera type, or

disporic, Allium, Veratrum lobelianum, Endymion,

Scilla types, or tetrasporic, Adoxa, Fritillaria or

Drusa types). Synergids often with filiform apparatus. Antipodal cells

usually persistent, sometimes proliferating. Endosperm development usually

helobial (sometimes nuclear, rarely cellular), with distinct (large) micropylar

and (small) chalazal chambers usually developed. Endosperm haustoria chalazal

and/or micropylar or absent. Embryogenesis asterad or onagrad (sometimes

caryophyllad, chenopodiad, or solanad).

Fruit Usually a loculicidal

capsule (rarely septicidal, septifragal, poricidal, ventricidal, irregularly

dehiscent or indehiscent), a berry, nut or drupe (sometimes a nut-like

caryopsis, follicle, samara or schizocarp, or an assemblage of achenes,

drupelets or berrylets or a multifolliculus).

Seeds Exotesta usually with

thin phytomelan layer on epidermal cell walls. Perisperm usually not developed

(sometimes well developed, with lipids and proteins or compound starch grains).

Endosperm copious to sparse, often with starch (with simple or compound starch

grains), and/or lipids, aleurone and hemicellulose, or absent. Chalazosperm

developed or absent. Embryo straight to curved, well or poorly differentiated,

sometimes covered with discoid or conical embryostega, testal operculum and

surrounded by micropylar collar, with or without chlorophyll. Cotyledon one

(rarely with rudimentary additional cotyledon), terminal, sometimes

photosynthesizing, with closed sheath, usually unifacial (hyperphyllar;

sometimes bifacial), assimilating and haustorial, usually with two main

vascular bundles. Plumule lateral. Cotyledon hyperphyll elongate or compact,

dorsiventrally flattened, assimilating or not assimilating, sometimes modified

into haustorium or nutrient-storing organ. Hypocotyl internode short to long

(sometimes modified into nutrient-storing organ), or absent. Mesocotyl present

or absent. Coleoptile present (sometimes modified into plumule envelope), with

or without lamina, or absent. Collar rhizoids or collar roots sometimes

present. Radicula unbranched, usually poorly developed, contractile, persistent

or ephemeral (rarely absent). First leaf usually orientated at 180o

to plane of cotyledon (in most angiosperms orientated at 90o to

plane of cotyledons).

Cytology Membrane complexes

absent. Paracrystalline bodies with closely spaced subunits.

DNA Duplication producing

monocotyledonous nuclear genes LOFSEP and FUL3 (latter

duplication of gene AP1/FUL). Nuclear genes PHYA,

PHYB and PHYC present. Nuclear gene PHYE lost.

AP3 expression localised on tepal edges. Mitochondrial genes

rpl2 and sdh3 lost.

Phytochemistry Flavonols

(kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin, isorhamnetin, syringetin, etc.),

O-methylated flavonols, laricitrin, flavonol glycosides,

dihydroflavones, flavones, flavone glycosides, flavonoid sulfates,

biflavonoids, isoflavones, biflavones, flavanones, homoisoflavanones,

hydroxyflavonoids, aurones, luteolin, apigenin, cyanidin, delphinidin,

pelargonidin, malvidin, etc., anthoxanthins, deoxyanthocyanins, ethereal oils

consisting of mono-, di-, tri- and sesquiterpenes, proanthocyanidins,

phenylpropanoids and related curcumins (diarylheptanoids), caffeic acid,

chalcones, 6-hydroxyapigenin methyl ethers, diterpenes, triterpenes, oxidized

tetracyclic and pentacyclic diterpenes and triterpenes, sesquiterpenes,

chalcones, (ent-)epicatechin-4 (non-hydrolyzable tannin), protocatechinic

aldehyde, catechins, proanthocyanidins, cinnamic acid, daphnetin, juncosol,

caffeic acid derivatives (including caffeic acid sulfate), chlorogenic acid,

phenolic glycosides, polyphenolic glycosides with caffeic acid, phenolic

sulfates (sulfonated phenolic acids), phenols, norbelladine alkaloids (toxic

tyrosine derivatives), isoquinoline alkaloids (benzylisoquinoline alkaloids

rare), tryptophane- or tyramine-derived alkaloids, pyrrolizidine alkaloids as

1-aminopyrrolizidine derivatives, indole alkaloids, steroidal alkaloids,

quinines, polyhydroxyalkaloids, piperidine alkaloids, lactone alkaloids

(tuberostemonine), tropane alkaloids, cholestane glycosides (cardiotoxic

bufodienolides, cardenolide glycosides and spirostanol glycosides),

tyrosine-derived cyanogenic glycosides etc., steroidal saponins and sapogenins,

chelidonic acid, cyanogenic compounds (e.g. cyanogenic glycosides), chrysazine,

anthrones (e.g. anthrone-C-glycoside in leaves),

tetrahydroanthracenones, naphthoquinones, quinonoid pigments, resins, aromatic

acids and ketones, benzoic quinones, shikimic acid- or polyacetate-derived

arthroquinones, nepodin, dianellidin, stypandrol, dianellidone, magniferin

(glycosylic xanthone), chromones, lactone, phenylpyrones, phenylphenalenones

(perinaphthenones), arylphenalenones, phenolic amines, polyamines, acetidine

carbonic acid, ascorbic acid, tuliposides (glucose esters), allyl sulfides,

allyl disulfides, propyl sulfides, vinyl disulfides, alliin, propionaldehyde,

propionthiol, hydroxycinnamic acid, eicosanyl arachidate, crocein,

phytosterols, 5-alkylic- and 5-alkenylic resorcinols, homogentisic acid and

their glycosides, p-coumaric acid, -sitosterol, ceryl alcohol, amines, non-protein amino

acids (tricine [zwitterionic amino acid], S-methylcysteine, etc.),

meta-carboxysubstituted aromatic amino- and γ-glutamic peptides,

acaroid resins, oxypipe colanic acid (polysaccharide), saccharose esters of

diferulic or triferulic acid, and stem fructans present.

p-hydroxybenzaldehyde (lignin component) at least often present.

Ellagic acid, ellagitannins, lignans, and neolignans not found. Triterpene

saponines rare. Hemicelluloses present as xylans.

Fossils Monocotyledon fossils

are often difficult to distinguish from other basal angiosperm groups. However,

numerous fossils more or less similar to extant Liliidae have been

described during the last decades. Many of these have not been assigned to any

particular extant clade.

- The oldest known fossil Liliidae are

120–110 My old and resemble Pothooideae (Araceae).

- Acaciaephyllum from the Potomac

Group of eastern North America represents herbaceous plants with sheathing leaf

bases and an acrodromous reticulate venation. The taxonomic affiliation is

highly questioned, although they have been assigned to the monocotyledon stem

group (Doyle 1973, etc.).

- A number of fossilized leaves and stems of

monocotyledons have been found in Turonian layers in Israel and in the

Maastrichtian Deccan Intertrappen Beds of India. These include

Geonomites, Limnobiophyllum dentatum, Plumafolium

bipartitum, Pontederites eichhornioides, Potamogetophyllum

mite, Quturea fimbriata, Typhacites negevensis,

Aerophyllites intertrappea, and Aerorhizos harrissii.

- Spinizonocolpites is a Late

Cretaceous pollen fossil strongly resembling the extant Nypa (Arecaceae). Early

Cretaceous pollen types which have been referred to monocotyledons due to their

characteristic monocot morphology include the sometimes frequently occurring

Liliacidites and Similipollis.

- Shuklanthus superbum is a racemose

inflorescence found in the Maastrichtian layers of the Indian Deccan

Intertrappean Beds, whereas Viracarpon from the same layers represents

an infructescence that may actually belong to the same species. The unisexual

flowers are trimerous with six tepals and six uniovulate carpels. The fruits

consist of single-seeded drupelets.

- Deccananthus savitrii from the

Deccan Intertrappean Beds of India is a trimerous flower with six tepals and

six stamens. The pollen grains are trichotomosulcate and the ovary is

trilocular.

- Tricoccites trigonum comprises

three-seeded trilocular drupes, likewise from the Deccan Intertrappean Beds,

resembles extant Arecaceae and

Pandanaceae.

- Eriospermocormus indicus is a

fossilized corm from the Deccan Intertrappean Beds. It is somewhat similar to

the Eriospermum (Ruscaceae), but

its systematic affiliation is uncertain.

Systematics Acorus is

sister to the remaining monocots and Alismatales

successive sister-group to the remainder.

A widely accepted hypothesis is that

Liliidae have evolved from helophytic (or even aquatic) ancestors.

Numerous adventitious roots replacing an ephemeral main root (instead of a

single tap-root), sympodial growth, atactostele (vascular bundles scattered in

stem), absence from normal secondary lateral growth, and usually linear leaves

lacking normal lamina are characteristics of the monocots which have been

explained through this hypothesis. Moreover, most members of the two basal

monocot clades, Acorus and Alismatales,

are helophytes or aquatic.

Reticulately veined pseudolamina and baccate

fruits – probable adaptations to forest habitats – have evolved in parallel

in many monocotyledon clades. According to Givnish & al. (2005), baccate or

drupaceous fruits have evolved 21 times and reticulodromous venation perhaps

between 25 and 30 times during the evolution of Liliidae.

|

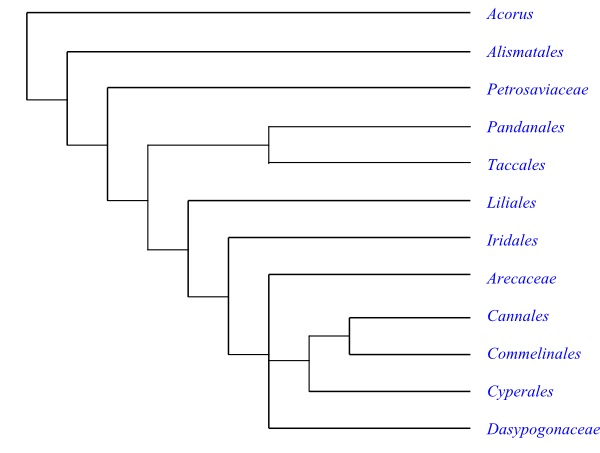

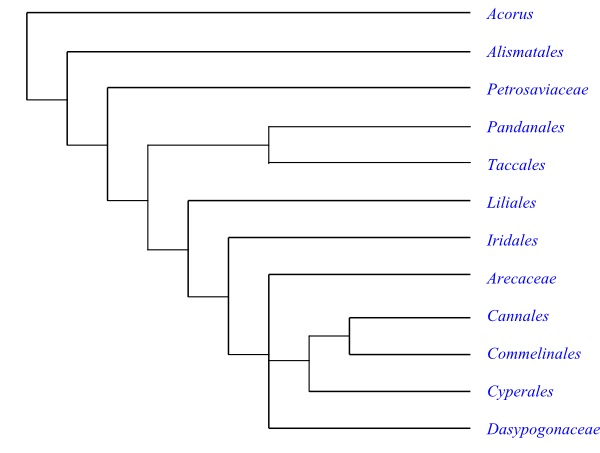

Phylogeny of Liliidae based on DNA

sequence data (Tamura & al. 2004; Chase & al. 2006; Graham

& al. 2006; Soltis & al. 2011). Acorus and Alismatales

are supported by 100% (bootstrap-value) as successive sister-groups to

the remaining Liliidae. The clade [Pandanales+Taccales]

also has very high support. Liliales

and Iridales

are successive sisters to the remainder, the Commelinidae (a

clade bootstrap support of 100%)

|

Nartheciidae S. W.

Graham et W. S. Judd in Taxon 56: E25. Aug 2007

[Alismatales+[Petrosaviaceae+[Taccales+Pandanales]+[Liliales+[Iridales+Commelinidae]]]]

Potential synapomorphies: Ethereal oils

absent. Raphides present. Ptyxis (of pseudolamina) supervolute-curved or

variations of this principle. Endothecium developing directly from undivided

outer secondary parietal cells. Pollen grains boat-shaped. Sexine reticulate.

Tectum with finer sculpture at pollen ends. Endexine absent. Septal

(epithelial) nectaries often present (intercarpellary fusion often

postgenital). – Nartheciidae contain all monocotyledons except

Acorus.

Petrosaviidae S. W.

Graham et W. S. Judd in Taxon 56: E25. Aug 2007

[Petrosaviaceae+[Taccales+Pandanales]+[Liliales+[Iridales+Commelinidae]]]

Potential synapomorphies: Pseudolamina

developing from leaf base zone. Epidermis with bulliform cells. Stomata

anomocytic. Cuticular wax crystalloids sometimes as parallel platelets.

Colleters (squamulae intravaginales) absent. Starch grains simple,

amylophobic. Cyanogenic glycosides infrequent. – Petrosaviidae

comprise Liliidae except Acorus and Alismatales.

[[Taccales+Pandanales]+[Liliales+[Iridales+Commelinidae]]]

Potential synapomorphies: Nucellar cap

absent. Endosperm development nuclear.

Pandananae Thorne ex

Reveal in Novon 2: 236. 1992

[Taccales+Pandanales]

Potential synapomorphy: Outer integument

two (or three) cell layers thick.

[Liliales+[Iridales+Commelinidae]]

Synapomorphies other than from DNA

sequences have not been found.

[Iridales+Commelinidae]

Potential synapomorphy: Style long.

Commelinidae Takht.,

Sist. Filog. Cvetk. Rast.: 514. 4 Feb 1967 [sensu S. W. Graham et W. S.

Judd]

[Arecaceae+Dasypogonaceae+[Cyperales+Commelinanae]]

Potential synapomorphies: Unlignified

cell walls containing UV-fluorescent ferulic acid and coumaric acid

(fluorescence of unlignified cell walls caused by presence of ferulic and/or

coumaric acids). Vessel elements sometimes present in stem and leaves. Cells

with silica bodies present in leaves. Stomata paracytic or tetracytic.

Cuticular wax crystalloids sometimes Strelitzia type (as aggregated

rodlets resembling scallops of butter). Inflorescence indeterminate. Peduncle

bracteate. Filaments adnate to inner tepals (epipetalous). Pollen grains

containing starch. Embryo short and wide. Expression of B-class gene orthologue

of nuclear gene PISTILLATA probably restricted to androecium and inner

tepals.

[Cyperales+[Commelinales+Cannales]]

Potential synapomorphies: Primary cell

walls usually with glucurono-arabinoxylans. Stomatal subsidiary cells with

parallel divisions. Endosperm with starch.

[Commelinales+Cannales]

Potential synapomorphies: Inflorescence

a helicoid cyme (with many-flowered cincinnal branches). Tapetum

amoeboid-periplasmodial or invasive. Operculum of seed combined with micropylar

collar (micropylar collar formed at apex of outer integument, protruding as

orbicular wedge into megasporangium; sclerotic layer of seed coat discontinuous

at site of micropylar collar; collar sometimes with special rupturing layer).

Endotestal cells silicified.

[Ceratophyllum+Tricolpatae]

Potential synapomorphy: Ethereal oils

absent. – Ceratophyllum is sister to Tricolpatae in the

maximum-likelihood tree of Soltis & al. (2011), but recovered as

sister-group to Liliidae in the maximum-parsimony tree of the same

study.

Ceratophyllum has a large number of

autapomorphies, in part due to their highly specialized aquatic lifestyle.

Roots, vessels, stomata and cuticular waxes are absent and the perianth is

reduced. Even their pollen morphology – inaperturate (to indistinctly

monocolpate) and with very reduced exine – may be a result of adaptation to

an aquatic environment. The microsporogenesis is successive (like in monocots)

in some species and simultaneous (like in most eudicots) in others. Further

investigations of the pollen development in Ceratophyllum are

certainly critical to our understanding of pollen character optimization among

Tricolpatae.

Ceratophyllum share many

features with the majority of Liliidae, including ephemeral primary

root, closed stem vascular bundles, absence of interfascicular cambium, absence

of vessels in stem and leaves, perianth (if present) trimerous, and successive

microsporogenesis. On the other hand, it seems to be very difficult to find

morphological synapomorphies for the clade

[Ceratophyllum+Tricolpatae].

Tricolpatae M. J.

Donoghue, J. A. Doyle et P. D. Cantino in Taxon 56: E26. Aug 2007 (tricolpates,

eudicots)

Potential synapomorphies: Root epidermis

derived from root cap. Nodes 3:3 (trilacunar with three leaf traces). Foliar

lamina usually developing from leaf apex. Stomata anomocytic. Cuticular wax

crystalloids as clustered tubuli (Berberis type), with nonacosan-10-ol

as dominating wax. Chloranthoid leaf teeth possibly apomorphous (also in Chloranthaceae).

Flowers cyclic, sometimes dimerous. Outer tepals (sepals) with three traces.

Inner tepals (petals) with one trace. Stamens few, individually antetepalous

(also in Lauraceae).

Polyandry (secondary) widespread. Initial primordia sometimes five, ten or

annular, sometimes centrifugally developing. Filaments fairly slender. Anthers

basifixed. Microsporogenesis simultaneous. Pollen tetrads tetrahedral. Pollen

grains triaperturate. Apertures in pairs at six points on young tetrad,

according to Fischer’s rule. Cell division (cleavage) centripetal. Pollen

wall with endexine. Carpels with complete postgenital fusion. Style solid (not

hollow). x = 7. Vacuolar crystal formation associated with membranes and

paracrystalline bodies with widely spaced subunits. Myricetin and delphinidin

scattered, asarone absent (present in some asterids).

Fossils The oldest known

fossil tricolpate pollen grains have been found in Late Barremian to Early

Aptian strata in England, Portugal, Israel, Egypt, tropical West Africa, and

eastern North America. The exine is finely to coarsely reticulate or striate,

with a columellate infratectum. Examples of early fossils not assigned to any

particular eudicot clade are as follows.

- Sinocarpus decussatus comprises

parts of infructescences and leaves from the Aptian of China. The decussate

leaves are provided with chloranthoid teeth and the fruits are formed by three

or four whorled and partially connate carpels.

- Hyrcantha karatscheensis is

represented by reproductive axes and fruits from the mid-Albian of Kazakhstan.

The gynoecium is composed of three to five free carpels.

- Ternariocarpites floribundus is an

infructescence with free carpels from the Albian of the Russian Far East. The

fruitlets are follicular and the five tepals are persistent.

- Ranunculaecarpus quinquecarpellatus

from the Albian of East Siberia consists of an apocarpous fruit with five

follicular carpels. The fossilized bicarpellate syncarpous fruit of

Araliaecarpum kolymense emanates from the same Siberian locality.

- The Cenomanian flower Callicrypta

chlamydea from eastern Siberia has a perianth consisting of three whorls,

stamens/staminodia and six free carpels.

- Cathiaria zhilinii is known from

several localities from eastern Europe to Japan. It comprises fruiting

structures with monocarpellate single-seeded fruits from the Cenomanian to the

Coniacian.

- Numerous follicular fruits (Agapitocarpus

emisxus, Chontrocarpus pachytoichus, Maiandrocarpus

moirasmenus, Malliocarpus batrachoides, Mitocarpus

elegans, Xylocarpus rhitidodes, Zeugarocarpus) have been

found in Late Santonian to Early Campanian layers of Sweden. The different

fossil species are relatively similar to each other. The gynoecium is

apocarpous or monocarpellate, the carpels are plicate and the multiple ovules,

when known, are anatropous and bitegmic. Traces of tepals are absent.

Systematics Apart from the

unresolved relationship (beyond Ranunculaceae)

between Proteales,

Sabiaceae and the

remaining Tricolpatae, Sabiaceae have been

recovered as sister to Proteales in several

studies (Qiu & al. 2006; Moore & al. 2008; Burleigh & al. 2009;

Moore & al. 2011; Soltis & al. 2011), yet with weak to moderate

support. Hence, I am apt to include Sabiaceae in Proteales. In other

analyses, Sabiaceae

have been identified (with weak support) as sister to Tricolpatae

except Ranunculales and

Proteales (Soltis

& al. 2008), to Tricolpatae except Ranunculales

(Worberg & al. 2007; Qiu & al. 2010; etc.), or even as sister to

Buxales (Kim & al. 2004). The recovered sister-group relationships

in this part of Tricolpatae largely depend on number and types of

sequenced genes (plastid and/or mitochondrial and/or nuclear genes).

In all, I have followed Moore & al. 2010,

Moore & al. 2011 and Soltis & al. 2011, since there phylogenies are

strongly supported.

[Proteales+Sabiaceae+[Trochodendrales+[Didymelales+Gunneridae]]]

Potential synapomorphy:

Axial/receptacular nectaries sometimes present.

[Trochodendrales+[Didymelales+Gunneridae]]

Potential synapomorphies: Mitochondrial

gene rps2 absent (lost). Benzylisoquinoline alkaloids absent.

Gunneridae D. E.

Soltis, P. S. Soltis et W. S Judd in Taxon 56: E27. Aug 2007

[Gunnerales+Pentapetalae]

Potential synapomorphies: Leaf margin

serrate. Compitum present. Duplication of floral organ identity B-class gene

paleoAP3 (yielding euAP3 and TM6 paralogs).

PI-dB motif present. Small deletion in the 18SrDNA frequently present.

Ellagic and gallic acids abundant.

Fossils In the Late Albian to

the Early Cenomanian of Nebraska, there are unambiguous fossils of pentamerous

heterochlamydeous flowers (with differentiated calyx and corolla) which are

assignable to the Gunneridae.

Systematics Several other gene

duplications seem to have taken place in the ancestors of either

Gunneridae or Pentapetalae (or sometimes even earlier), i.a.

duplication of nuclear floral regulatory genes AP1/FUL or

FUL-like gene (yielding euAP1, euFUL and

AGL79); duplication of nuclear gene RPB2; duplication of

AG-like C-class gene (yielding PLE and euAG

paralogs); duplication of nuclear genes AGL2/3/4 (yielding

SEP1 and FBP6) and AGL1/2/3, etc. (see, i.a., Kramer

& Zimmer 2006; Kramer & al. 2004; Kramer & al. 2006). The knowledge

of many of these duplications is insufficient for many critical clades (Proteales, Sabiaceae, Trochodendrales,

Didymelales,

Gunnerales,

Dilleniaceae,

Santalales,

Berberidopsidales,

etc.). Consequently, it is still impossible to optimize them convincingly on

the tree.

Since Gunnerales are sister

to Pentapetalae, detailed knowledge of floral development in

Gunnera and Myrothamnus is important for our interpretation

of floral characters in the crown group of Tricolpatae. The flowers of

Gunnerales are

strongly adapted to wind pollination, a fact that makes it even more difficult

to draw conclusions on homologies. Furthermore, the organization of the

androecial and perianth whorls are more similar to basal Tricolpatae

than to Pentapetalae.

Pentapetalae D. E.

Soltis, P. S. Soltis & W. S. Judd in Taxon 56: E27. Aug 2007

Potential synapomorphies: Root apical

meristem closed. Flowers pentamerous, with whorled floral parts. Calyx/sepals

and corolla/petals distinct. Sepals enclosing flower in bud (sepals and petals

encircling floral axis). Sepals with three or more traces. Petals with one

trace. Nectariferous disc present. Stamens twice the number of sepals/petals

(sometimes numerous, but then usually fasciculate), developing

internally/adaxially to corolla whorl and successively alternating from five

(ten) primordials, and/or centrifugally. Pollen grains tricolporate. Carpels

five (although three also frequent; when carpels two, then superposed). Style